1. Introduction

Perovskite-supported catalysts have received a great deal of attention recently because they offer the possibility of redispersing the metal if the crystallites become large due to sintering. Redispersion in these so-call “intelligent” catalysts occurs when the metal cations become part of the bulk lattice under oxidizing conditions, and then ex-solve back to the surface upon high-temperature reduction [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Originally proposed for use in automotive-emission-control catalysis, the idea has also shown promise for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) anodes [

9,

10] and steam-reforming catalysts [

11,

12,

13], due, in part, to the improved thermal stabilities, but also due to improved tolerance against coking [

14,

15].

The application of perovskite supports has been limited due to the low specific surface areas of the perovskites, the sluggish kinetics for ingress and egress of metal particles, and the fact that some ex-solved metal remains embedded in the bulk, as discussed in more detail elsewhere [

16]. Our group has prepared thin films of different perovskites on high-surface-area MgAl

2O

4 using Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) in order to circumvent these limitations. For the materials to maintain a high surface area, the film thickness is limited to approximately 1 nm. This is demonstrated by the fact that a 1-nm film of SrTiO

3 on a 200-m

2/g support would have 0.96 g SrTiO

3/g of support, which results in a significantly lower specific surface area due to both the increased sample mass and decreased pore sizes of the sample. Although metals that are supported on these thin-film supports are not catalytically identical to bulk, ex-solution metals [

17], many of their properties are similar. For example, most of these catalysts are only active after high-temperature reduction [

18]. Perovskite-supported, Ni catalysts also exhibit a high tolerance against coking [

19,

20]. Finally, supported Pt catalysts that are based on both thin-film and bulk perovskites showed similar differences from conventional Pt catalysts in their relative inactivity for hydrogenation reactions when compared to oxidation reactions [

18].

There are indications that some of the support effects that are associated with perovskites are due to the formation of chemical bonds with the metal. First, the nature of interactions is metal and perovskite specific, as expected when chemical bonding is important. While Pt and Rh can enter the bulk CaTiO

3 lattice and both metals exhibit strong support interactions in their thin-film variants, Pd cannot be doped into CaTiO

3, and Pd supported on CaTiO

3 films shows normal behavior [

17,

18]. Metal-perovskite interactions were also shown to depend on the perovskite composition in a comparison of Rh catalysts that are supported on thin films of CaTiO

3, SrTiO

3, and BaTiO

3 [

17]. Rh interacted very strongly with CaTiO

3, but only weakly with BaTiO

3. A second piece of evidence for bonding interactions is that the perovskite support can change the thermodynamic properties for oxidation of the supported metal. This was demonstrated for Ni on LaFeO

3 films, where the equilibrium constant for the reaction Ni to NiO was observed to shift by four orders of magnitude to lower PO

2 in the presence of the perovskite [

20].

A better understanding of the nature of metal-perovskite interactions is clearly required before these materials can find wider application. In the present study, the equilibrium properties for Ni oxidation were examined on thin films of CaTiO3, SrTiO3, and BaTiO3 that were supported on MgAl2O4. Ni-based catalysts are convenient for this comparison, because previous work has shown that the support can change the equilibrium constant for Ni oxidation to NiO by a significant amount. For the reaction, , the equilibrium constant, , is equal to and is given by exp (-ΔG/RT), where ΔG is the free energy of reaction. , and therefore ΔG, can be obtained by measuring the at which both Ni and NiO exist in equilibrium. We will show that, similar to what was observed for Rh on these perovskite supports, Ni interacts most strongly with CaTiO3, followed by SrTiO3 and BaTiO3.

2. Results

Table 1 provides a list of the samples that were used in this study, together with some of their key properties. The CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, and BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 supports were prepared while using procedures that are identical to those used in an earlier study of the support effects on Rh [

17]. As in that case, the targeted perovskite film thicknesses were 1 nm, assuming that the perovskite film densities were the same as that of the corresponding bulk perovskites and that the 120-m

2/g MgAl

2O

4 was uniformly covered. The Ni loadings were achieved using five ALD cycles of the Ni precursor. The properties that are shown in the Table were measured after the sample had been oxidized and reduced five times at 1073 K in order to ensure that the samples had reached an equilibrium state.

The perovskite-containing samples that are listed in

Table 1 were analyzed by Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (STEM/EDS) and XRD. In all cases, the samples were pretreated while using five redox cycles at 1073 K before the measurements were performed. The results are shown after oxidation at 1073 K and after reduction at 1073 K.

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the STEM/EDS results for the oxidized and reduced samples. For the oxidized samples, the images for each of the three samples were indistinguishable from that of the MgAl2O4 support; and, the EDS maps showed a spatial distribution of A-site cations, Ti, and Ni that matched well with the Mg and Al variations. All of this implies that each of the species deposited by ALD are uniformly distributed over the surface of the MgAl

2O

4 support and remain uniformly distributed, even after redox cycling. The CaTiO

3, SrTiO

3, and BaTiO

3 films remained largely unchanged after reduction at 1073 K, but Ni particles were formed on each of the three samples after this treatment. The Ni particles appeared to be slightly smaller for Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, ~10 to 20 nm, and largest on Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, ~30 to 50 nm, with Ni/SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 in between. It is noteworthy that the formation of Ni particles was reversible on each of the samples, since the uniform Ni films were restored by oxidation.

Figure 4 reports the XRD patterns for the oxidized and reduced samples. For oxidized Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 and Ni/SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, all of the peaks can be assigned to either the MgAl

2O

4 support or the corresponding perovskite phase. Upon reduction, peaks that are associated with metallic Ni were also observed. For BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, there is significant overlap in the peak positions for BaTiO

3 and MgAl

2O

4; however, the relative ratio of peaks, particularly those that are centered at 32 and 37 degrees 2θ, make it clear that the major peaks are due to a mixture of MgAl

2O

4 and BaTiO

3. Small peaks that could be indexed to BaCO

3 were also observed on the Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 sample. Again, the XRD pattern of the reduced sample was unchanged, except for the additional features that are associated with metallic Ni.

As discussed elsewhere [

16], the presence of intense perovskite diffraction peaks for uniformly-deposited films that are nominally 1-nm thick suggests the formation of relatively large, two-dimensional crystals, randomly oriented with respect to the support. Based on the width of the peaks, the nominal sizes of the perovskite crystallites are 22 nm for CaTiO

3, 18 nm for SrTiO

3, and 18 nm for BaTiO

3. The particle sizes were also estimated from XRD peak widths for the Ni particles in the reduced samples. These gave reasonable agreement with the values that were obtained from STEM, with values of 21 nm for Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, 25 nm for Ni/SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, and 31 nm for Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4.

The extent of reduction was measured as a function of temperature for each of the samples in

Table 1, with results being shown in

Table 2. The samples were first oxidized at 1073 K in flowing air and then reduced in 10%H

2-He mixture at the indicated temperature for 30 min. The amount of oxygen required to completely oxidize the sample at 1073 K was then measured using flow titration. First, there was no measurable reduction of the CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 and SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 supports, even at 1073 K; but, there was some reduction of the BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 sample at the highest temperature. Therefore, with the exception of Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 at 1073 K, the results that are presented in

Table 2 indicate the extent of reduction of the Ni in each of the samples. For Ni/MgAl

2O

4, only 38% of the Ni was reduced at 773 K and 87% at 1073 K. That such harsh conditions are required for reducing some of the Ni may indicate that a fraction of Ni has reacted with the MgAl

2O

4 support after the five redox cycles at 1073 K, with Ni replacing Mg and forming NiAl

2O

4. For Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 and Ni/SrTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, a reduction of Ni was insignificant at temperatures below 1073 K. At that temperature, most of the Ni in these samples was reduced. There was some reduction of Ni at lower temperatures on Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, but 1073 K was again required for a majority of the Ni to be reduced.

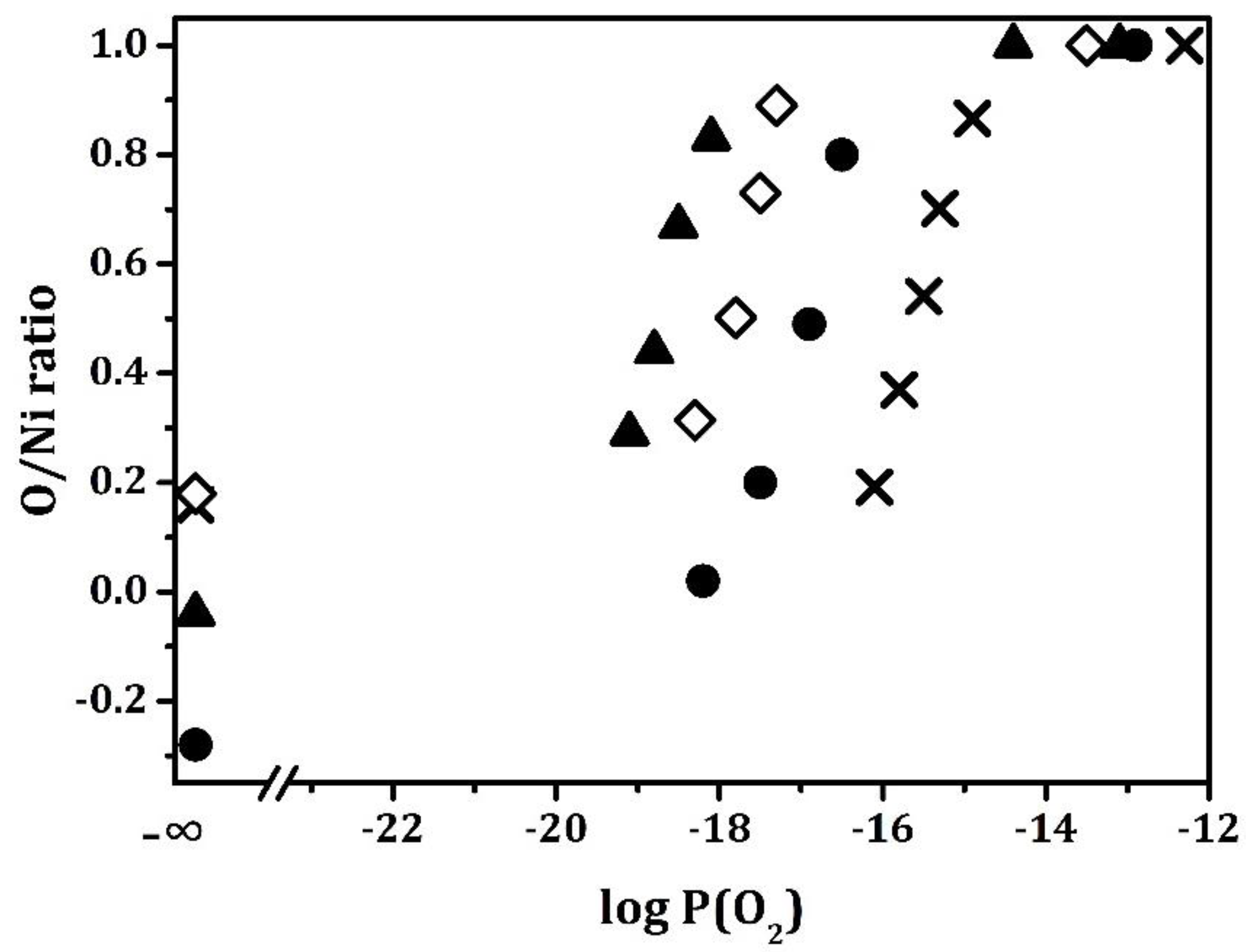

Coulometric Titration (CT) measurements were performed at 1073 K on each of the samples in order to better understand the effect of the perovskite supports on Ni reducibility, and the results are shown in

Figure 5. At this temperature, tabulated values of ΔG for bulk Ni would indicate that the equilibrium

should be 10

−14 atm. Data for Ni/MgAl

2O

4, reproduced here from a previous publication [

20], found that the amount of oxygen that was taken up by the sample was very close to the value obtained from the flow titration reported in

Table 2 and that oxidation of the Ni component occurred between 10

−15 and 10

−16 atm. The relatively small change in the equilibrium

from that reported for bulk Ni may be due to the Ni particle size or to interactions with the MgAl

2O

4 support. The equilibrium

for each of the perovskite-containing samples were shifted to lower values. The shift was the largest for Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, with oxidation occurring in the range of 10

−18 to 10

−19 atm, and the smallest for Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, between 10

−16 and 10

−17 atm. The Ni/BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 sample also took up slightly more oxygen in the CT experiments, which was in agreement with the flow-titration results. Even though the equilibrium

for Ni were shifted to lower values by interactions with the titanates, the changes were less than that previously observed with Ni/LaFeO

3/MgAl

2O

4 [

20], for which the equilibrium

was 10

−20 atm at 1073 K.

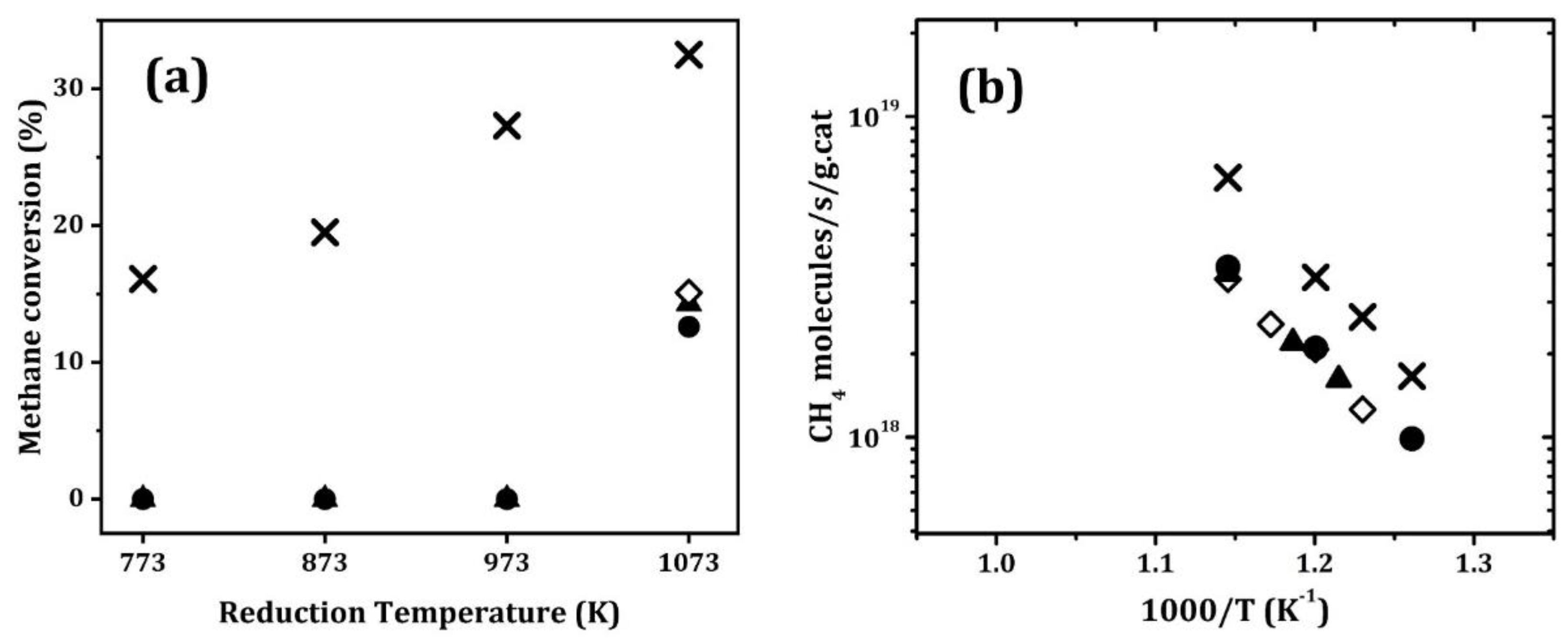

In order to determine whether these equilibrium properties affect catalytic activities, methane dry reforming (MDR) was investigated in all four Ni catalysts presented in

Table 1. In order to determine the effect of reduction temperature on each of the catalysts, methane conversions were measured at 873 K, while using 4.2% CH

4, 8.3% CO

2, and a 72,000 mL·g

−1·h

−1 Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV), and the results are shown in

Figure 6a. In each case, the catalysts were oxidized at 1073 K and then reduced in dry 10% H

2 for 30 min at the indicated temperatures before measuring the conversion. Ni/MgAl

2O

4 showed significant conversion after reduction at 773 K, and the conversions increased with the reduction temperature. This corresponds well to the flow-titration results, which indicated that Ni was somewhat reduced on this sample at 773 K, but that higher reduction temperatures increased the fraction of Ni reduction. Each of the perovskite-containing samples was completely inactive for reduction at temperatures below 1073 K, but showed reasonable activity after reduction at that temperature. The differential reaction rates are shown for each of the samples in the Arrhenius plots presented in

Figure 6b. The rates were about a factor of two lower on the perovskite-containing samples, but all of the catalysts showed a similar temperature dependence.

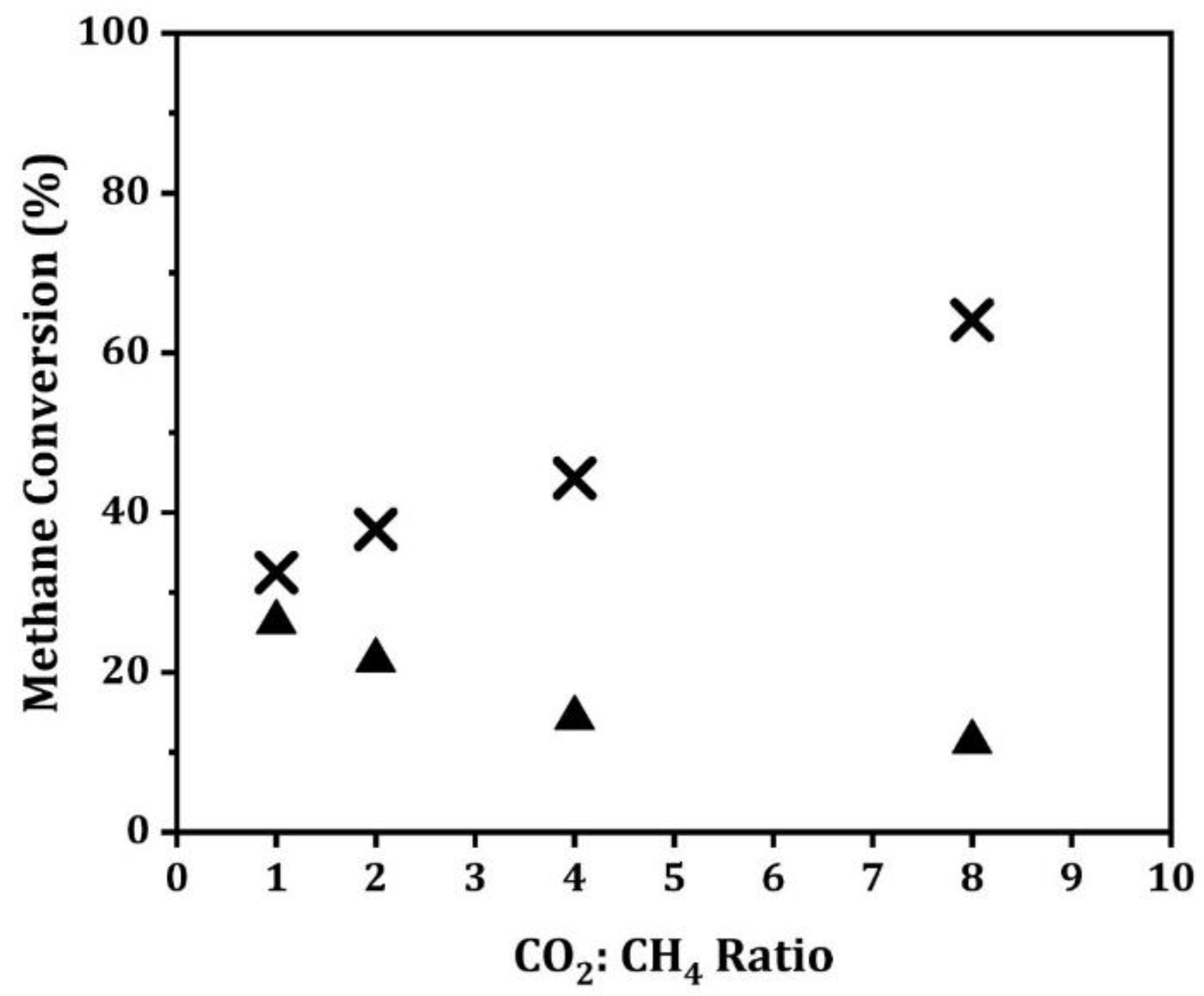

With Ni on LaFeO

3 films, the shift to lower

in the equilibrium constants for Ni oxidation is sufficient for Ni to be oxidized under some MDR reaction conditions [

20]. Although equilibrium constants for the titanates are significantly closer to that of bulk Ni, we investigated the MDR reaction on Ni/MgAl

2O

4 and Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 as a function of the CH

4:CO

2 ratio to see whether oxidation of Ni could also occur in these catalysts. The reaction was studied at integral conversions to produce CO and H

2; an equilibrium

is then established by the CO

2:CO ratio. For these measurements, the CH

4 flow rate was kept at 5 mL min

−1 and the CO

2 and He flows were tuned in order to achieve a desired CO

2:CH

4 ratio while keeping the space velocity the same. All of the conversions were measured at 873 K, and the results are shown in

Figure 7.

For the Ni/MgAl

2O

4 sample, we observed an increase in CH

4 conversion with increasing CO

2 concentration. This is the expected result for reactions with a positive reaction order. For Ni/CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4, the CH

4 conversion decreased with increasing CO

2 concentration, similar to what was previously observed for Ni/LaFeO

3/MgAl

2O

4 [

20]. This deactivation was not due to coking, since the conversions shown in

Figure 7 were stable and did not depend on whether the CO

2 concentration was increasing or decreasing. With the LaFeO

3-supported Ni, the deactivation was easier to observe because of the larger change in the equilibrium constant.

3. Discussion

Much of the work on perovskite-supported catalysts has focused on their exsolution properties and resistance to sintering. Thin-film perovskite supports are not identical to bulk perovskites, since the films are thinner than the nominal particle size of the metals, as discussed in more detail elsewhere [

16]. However, there are many similarities between the bulk and thin-film supports, which suggests that bonding interactions at the metal-perovskite interface are similar in these two cases.

In agreement with a previous study of Ni on LaFeO

3 films [

20], the work presented here demonstrates that the support can affect the oxidation thermodynamics of the Ni. Because the electronic effects of the support on a metal can only extend to a few atomic distances from the interface [

21], most of the Ni must be in direct contact with the support. Indeed, the STEM/EDS data indicate that is the case, at least for the oxidized samples. While thermodynamic properties do not indicate how large the kinetic barriers will be for reduction, the fact that the perovskite-supported catalysts require high temperatures for Ni reduction is additional evidence that there must be strong bonding interactions between the support and Ni.

Changes in Ni geometry upon different pretreatments are also worth noting. While previous studies suggested that interactions between Ni and some supports can lead to the redispersion of Ni, the conditions used were found to be harsher and the redispersion less complete than the results that are reported here [

22]. Our results would indicate that Ni atoms can migrate relatively long distances, along the surface of the perovskite thin films. It seems likely that Ni is incorporated as a strongly interacting phase, different from normal NiO, when supported on perovskite thin films, thus leading to the changes in equilibrium

.

Similar to what we observed in an earlier study of Rh on CaTiO

3, SrTiO

3, and BaTiO

3 films, support interactions depend on the A-site cations in this series. With Rh, the differences were much stronger than what we observed here with Ni. Rh that was supported on CaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 was almost unreducible and catalytically inactive, while the support effects for Rh on BaTiO

3/MgAl

2O

4 were negligible. The ordering of support interactions for Ni were the same as with Rh, in that CaTiO

3 interacts most strongly and BaTiO

3 least. How the A-site cations affect these interactions is uncertain. One possibility is that differences in the surface energies of these titanates change the surface terminations. For example, we have previously established by Low Energy Ion Scattering that CaTiO

3 films are terminated by Ca [

18] and it is possible that BaTiO

3 prefers to be B-site terminated due to the relative sizes of the ions. The free volumes for these three perovskite materials also change with the size of the A-site cations, and this may affect how easily catalytic metal cations can enter the lattice.

It is also interesting to ask why the differences for Ni on the various titanates were less than what was observed for Rh. One possible reason for this could be the nominal charge on the cations. It was previously shown that Pd, which, like Ni, is expected to exist in the +2 state when oxidized, does not interact with CaTiO

3 and it cannot enter the CaTiO

3 lattice [

18]. The ability of Rh to have multiple, stable oxidation states may also play a role in allowing Rh to interact more strongly with the perovskite lattices.

There is obviously much that we still need to learn about both ex-solution catalysts and the differences between bulk and thin-film perovskites. The fact that support interactions with these perovskite-supported metals are so specific to the compositions of the metal and the support represents both a challenge and an opportunity to tailor the catalytic properties for specific applications.

4. Materials and Methods

MgAl

2O

4 was prepared in our laboratory and had a surface area of 120 m

2/g after being stabilized by calcination to 1173 K, as described elsewhere [

17,

23]. The equipment and procedures used for ALD have also been reported previously [

24,

25]. The system is essentially a high-temperature adsorption apparatus that is attached to a mechanical vacuum pump. The evacuated samples were exposed to vapors from the precursors for approximately 10 min before purging excess precursor by evacuation. The precursors choices for the A-site cations were the same as one of the previous publications [

17], bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionato) calcium (Ca(TMHD)

2, Strem, Newburyport, MA, USA), bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionato) strontium hydrate (Sr(TMHD)

2, Strem, USA), and bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-3,5-heptanedionato) barium hydrate (Ba(TMHD)

2, Strem, USA) were chosen for Ca, Sr, and Ba ALD processes, respectively, and the exposure was carried out at 573 K. Because the TMHD ligands can only be removed at elevated temperatures by air [

26], the oxidation step of the ALD cycle for these precursors was performed by transferring the samples to a muffle furnace at 773 K for 5 min. For the TiO

2-ALD process, Titanium chloride (TiCl

4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was chosen as the precursor. TiCl

4 was kept at 363 K to ensure the generation of a sufficient amount of the precursor vapor. The deposition and the oxidation were both performed at 423 K. For the deposition half cycle, the samples were exposed to TiCl

4 vapor for three times for 1 min. After that, humidified air (10% water content) was introduced to the sample to ensure complete oxidation. Ni was also deposited by ALD while using Ni(TMHD)

2 (Strem, USA) as the precursor and a deposition temperature of 523 K.

The ALD growth rates were measured gravimetrically and checked by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES, Spectro Genesis). The dissolution processes were performed at 333 K overnight while using 10 mL of

aqua regia for the samples. After that, the solutions were diluted to suitable ranges for ICP measurements. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku MiniFlex diffractometer that was equipped with a Cu Kα source (λ = 0.15416 nm) and then patterns for 2 theta range from 20 to 60 degrees were recorded. BET surface areas were measured while using homebuilt equipment at 78 K [

24].

Ex-situ Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (STEM-EDS) measurements were performed using a JEOL NEOARM operated at 200 kV.

The rates for methane dry reforming were determined from differential conversions in a 0.25-inch, quartz, tubular-flow reactor at atmospheric pressure, with products analyzed while using a gas chromatograph (SRI 8610C) that was equipped with a TCD detector. The catalyst loadings were 100 mg for all of the samples. The total gas flow rate was maintained at 120 mL min−1. Methane flow was kept at 5 mL min−1 throughout the measurements. CO2 and He flows were adjusted to achieve different CO2:CH4 ratios while maintaining a constant flow rate.

The reducibilities of the samples were quantified by flow titration and Coulometric Titration (CT), as described in detail elsewhere [

25]. The flow-titration experiments were performed in a tubular reactor at 1 atm with 200-mg samples. After reducing the samples in flowing H

2 at desired temperatures, followed by purging with He, the samples were exposed to dry air at 1073 K at a flow rate of 5 mL min

−1 while monitoring the reactor effluent with a mass spectrometer. The O

2 uptake was then determined by integrating the difference between the N

2 and O

2 signals in the effluent. Equilibrium constants for oxidation of Ni were probed by CT at 1073 K. In a CT experiment, 500-mg samples were placed in the center of a YSZ (Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia) tube that had Pt paste on the inner wall and Ag paste on the outer wall. After flowing a mixture of 10% H

2, 10% H

2O, and 80% He over the sample at 1073 K, the tube was sealed with cajon fittings. The known quantities of oxygen were then electrochemically pumped into or out of the YSZ tube by applying a known charge across the metal electrodes using a Gamry instruments potentiostat. The equilibrium

was calculated from the electrode open-circuit potential while using the Nernst Equation after allowing the system to come to equilibrium with the electrodes at open circuit.