Synthesis of Aluminum-Based MOF and Cellulose-Modified Al-MOF for Enhanced Adsorption of Congo Red Dye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

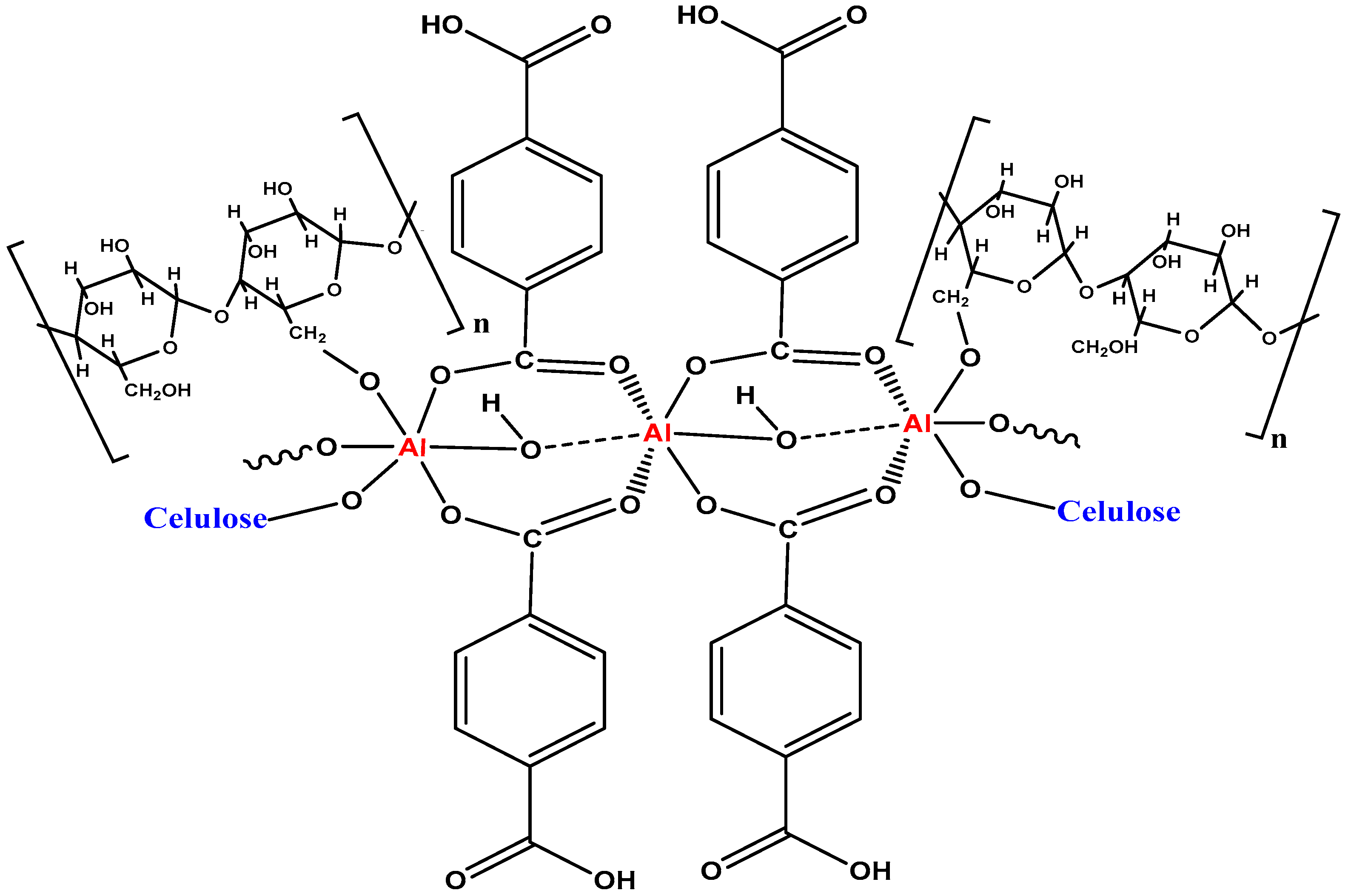

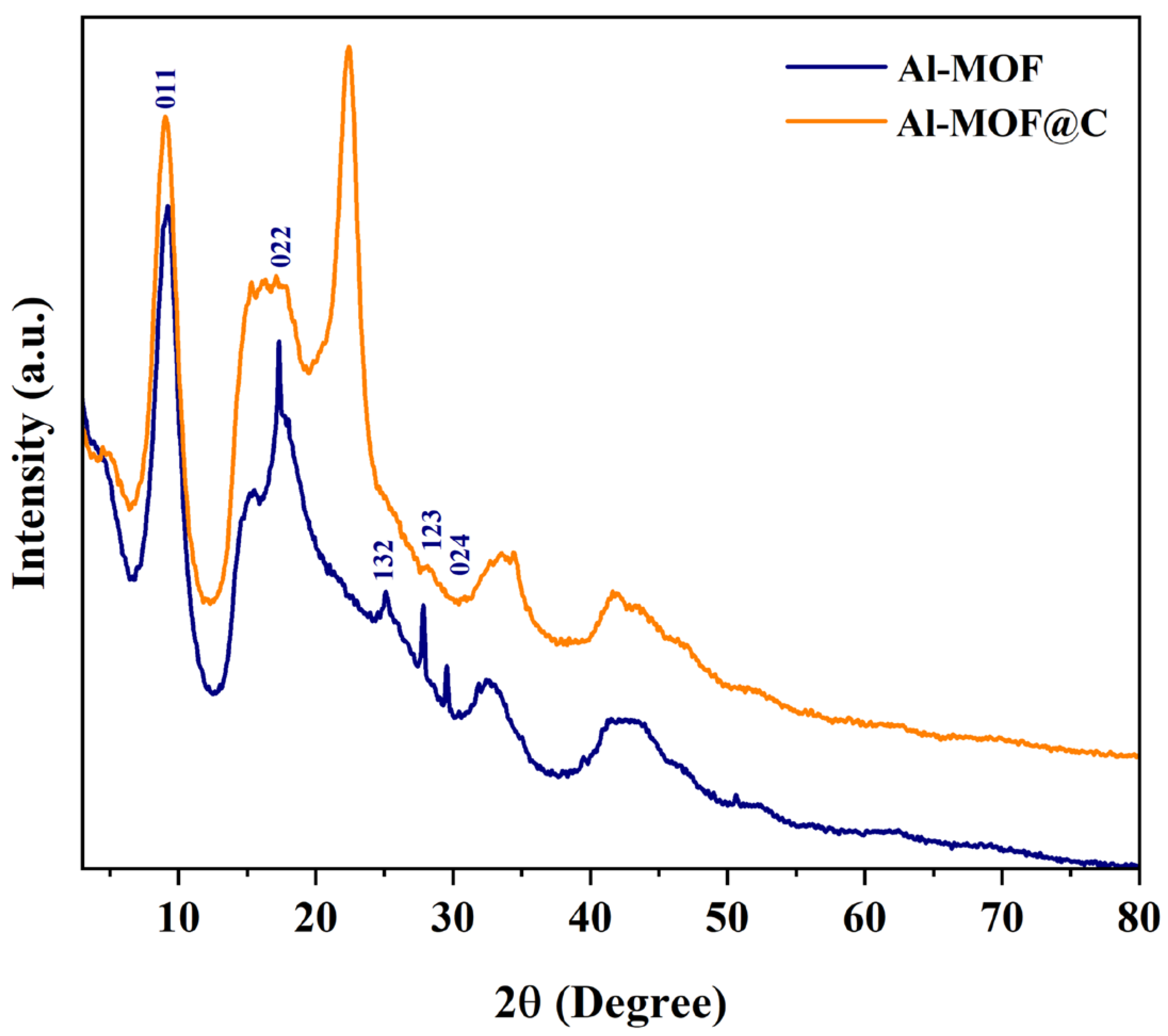

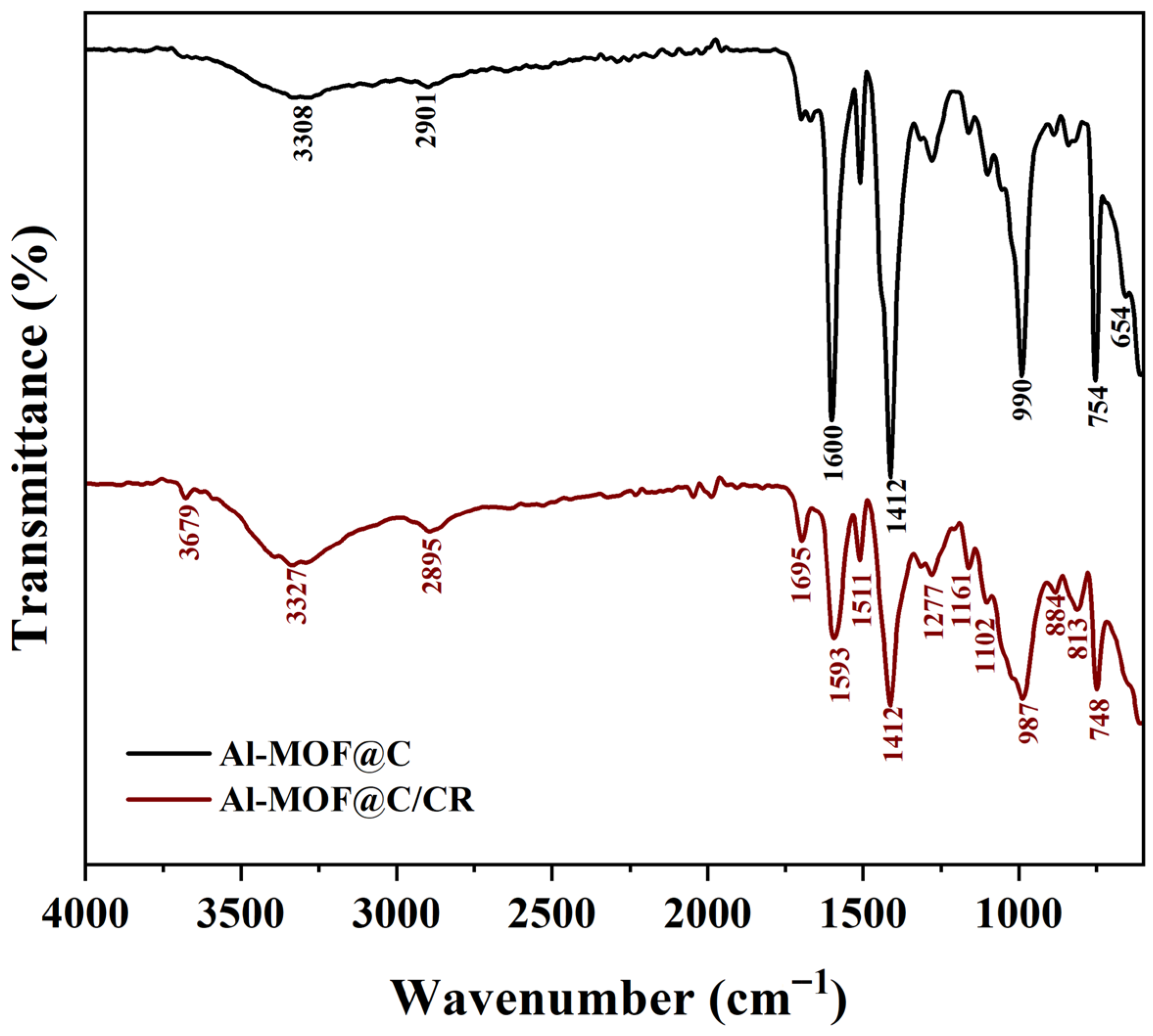

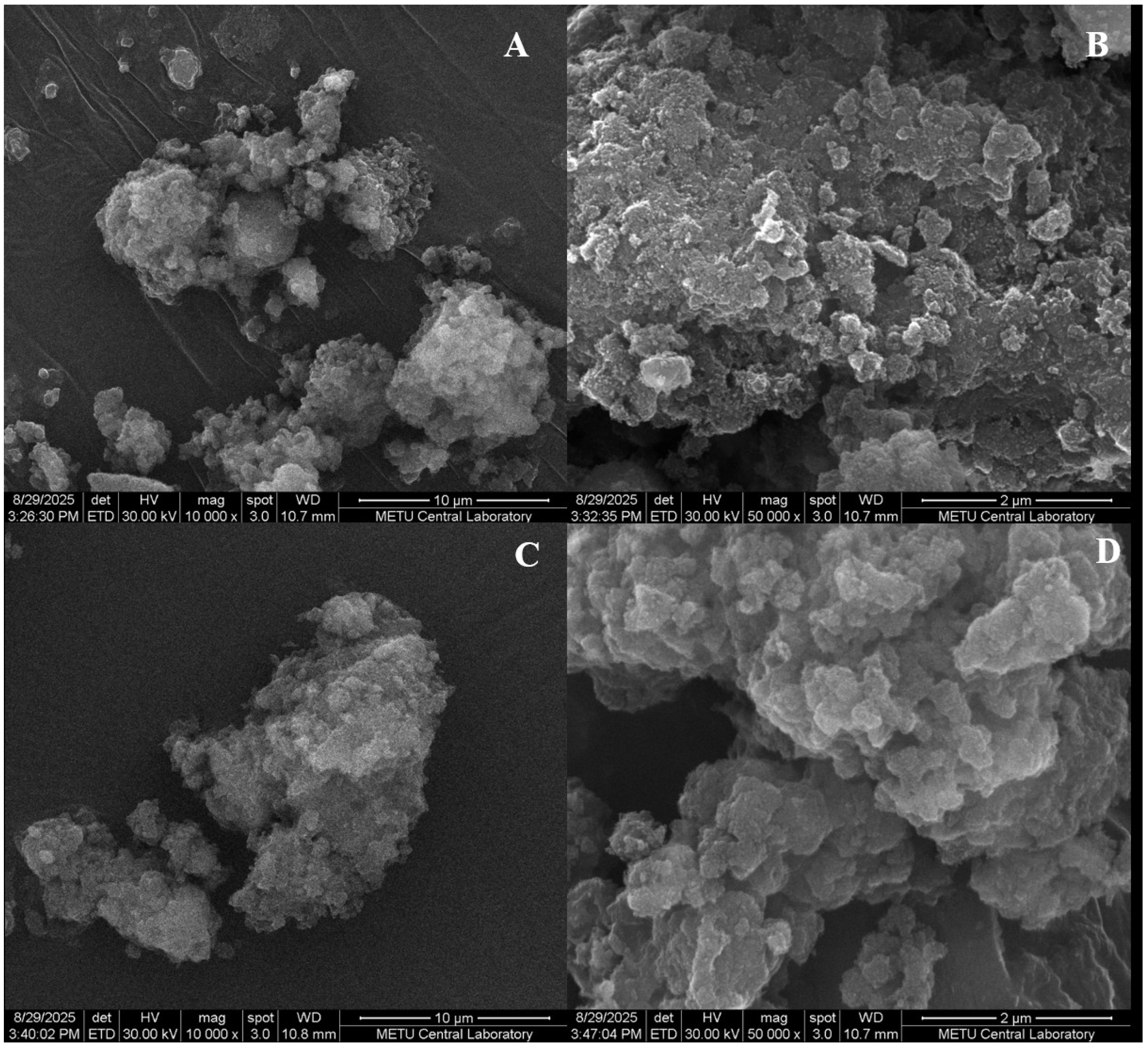

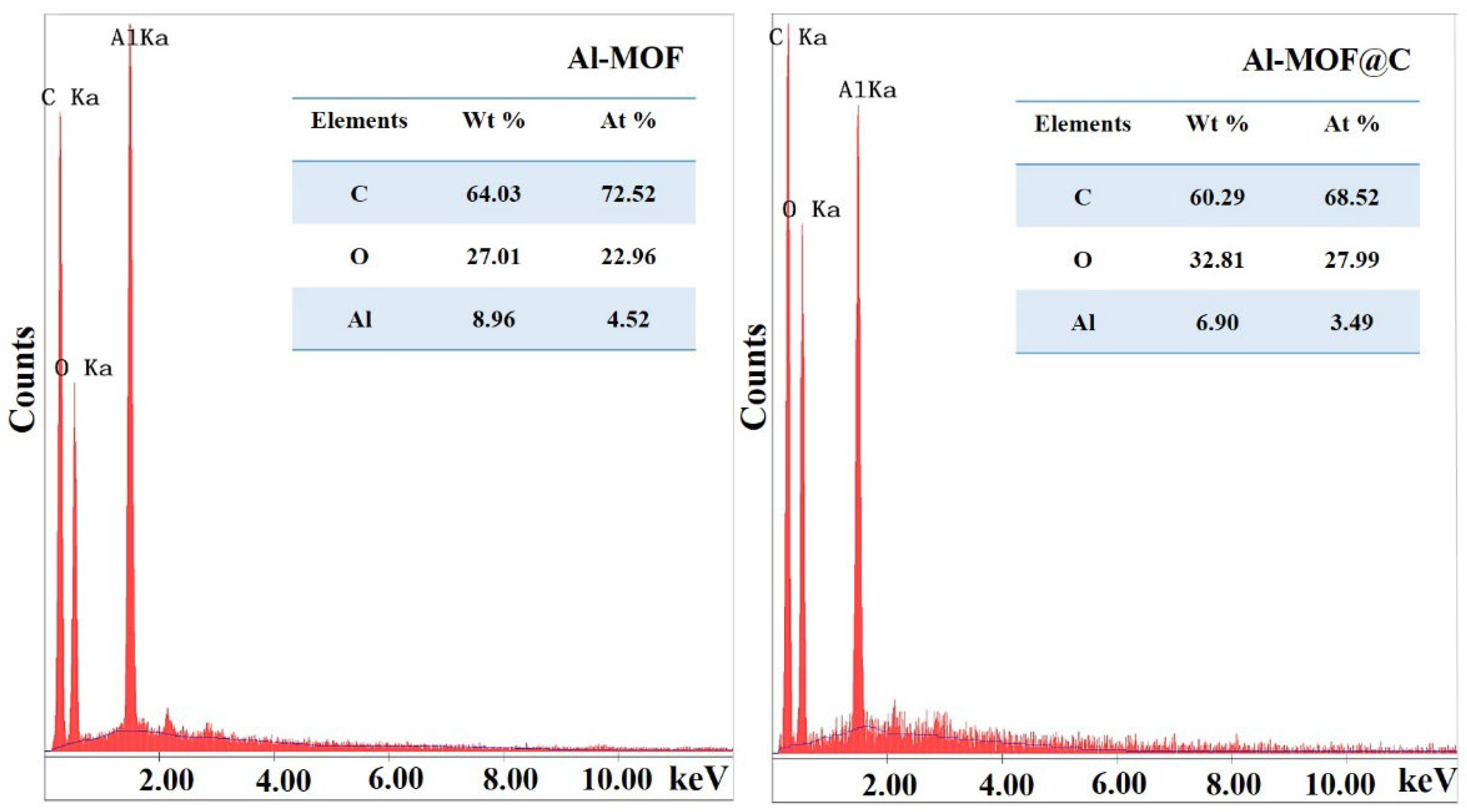

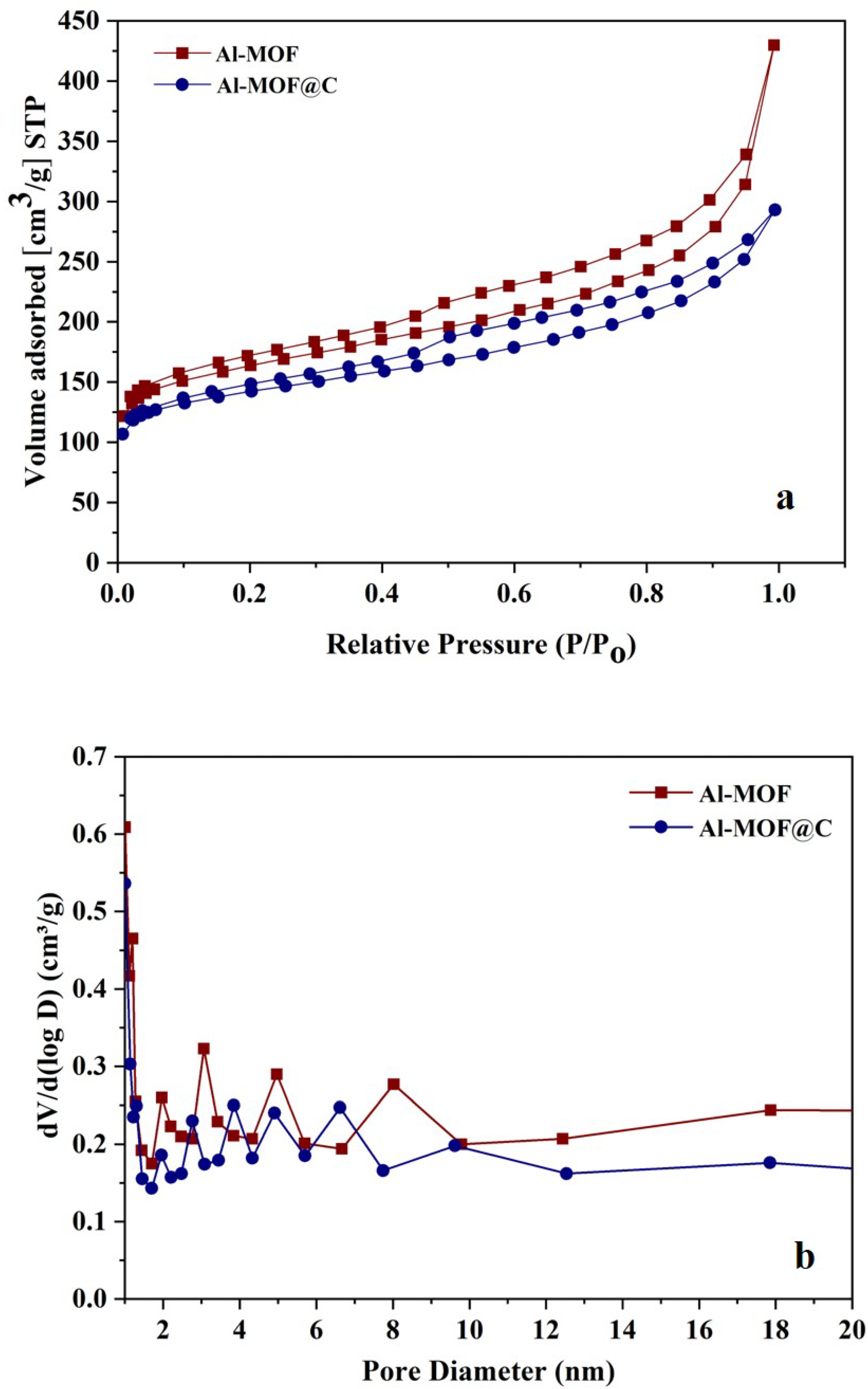

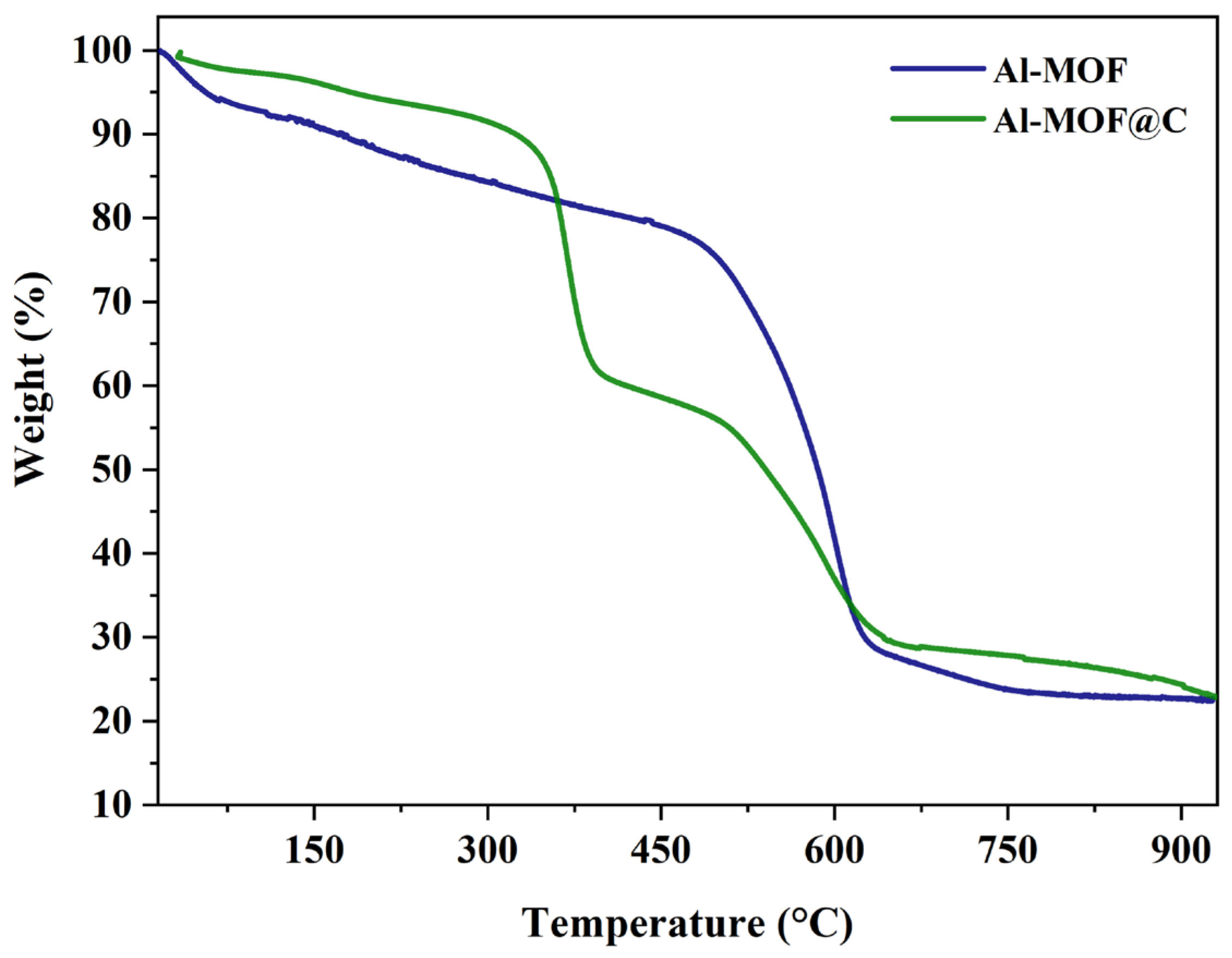

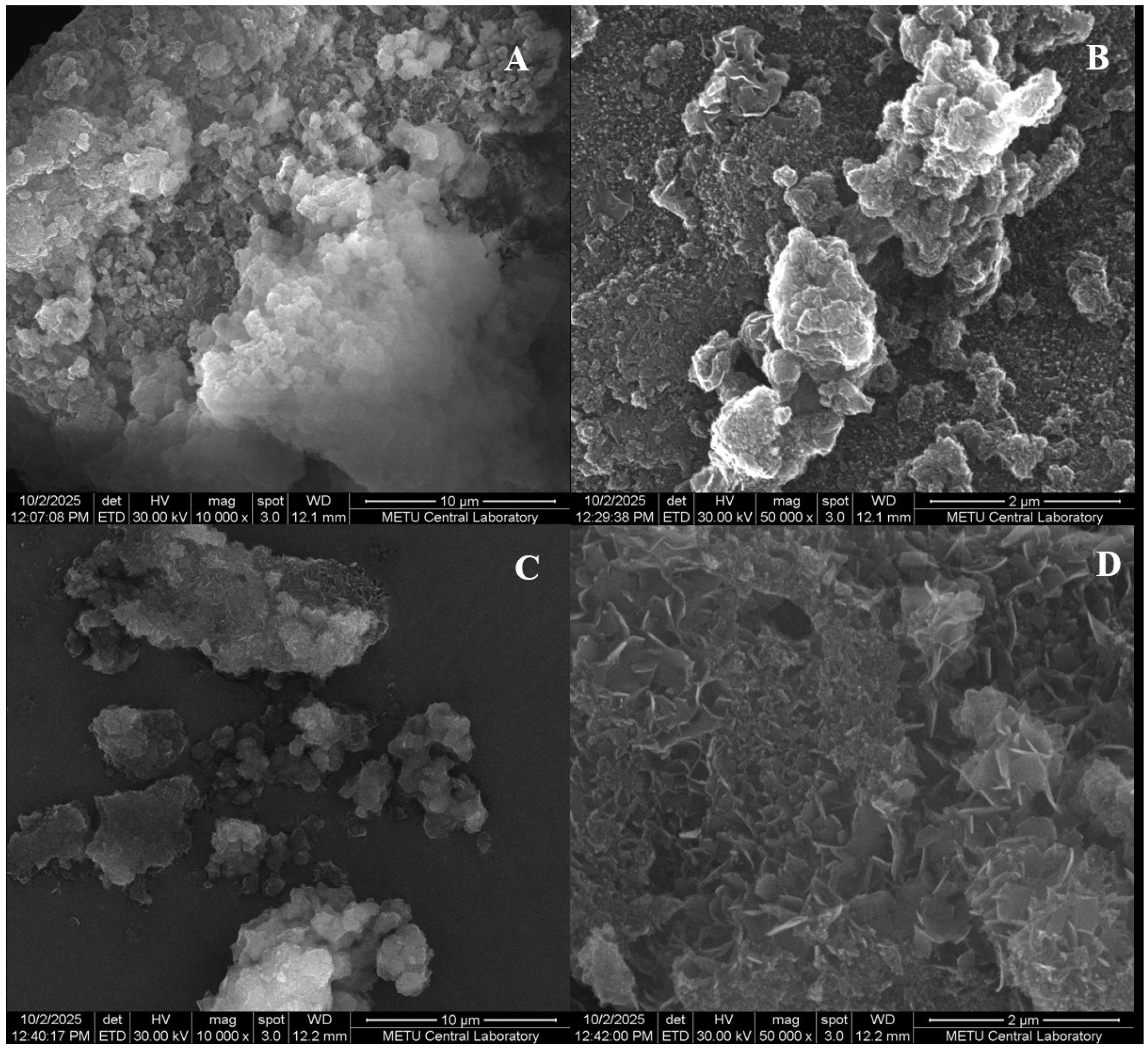

2.1. Structural Characterization of Al-MOF and Al-MOF@C

2.2. Adsorption Studies for Removal of Anionic Congo Red (CR) Dye

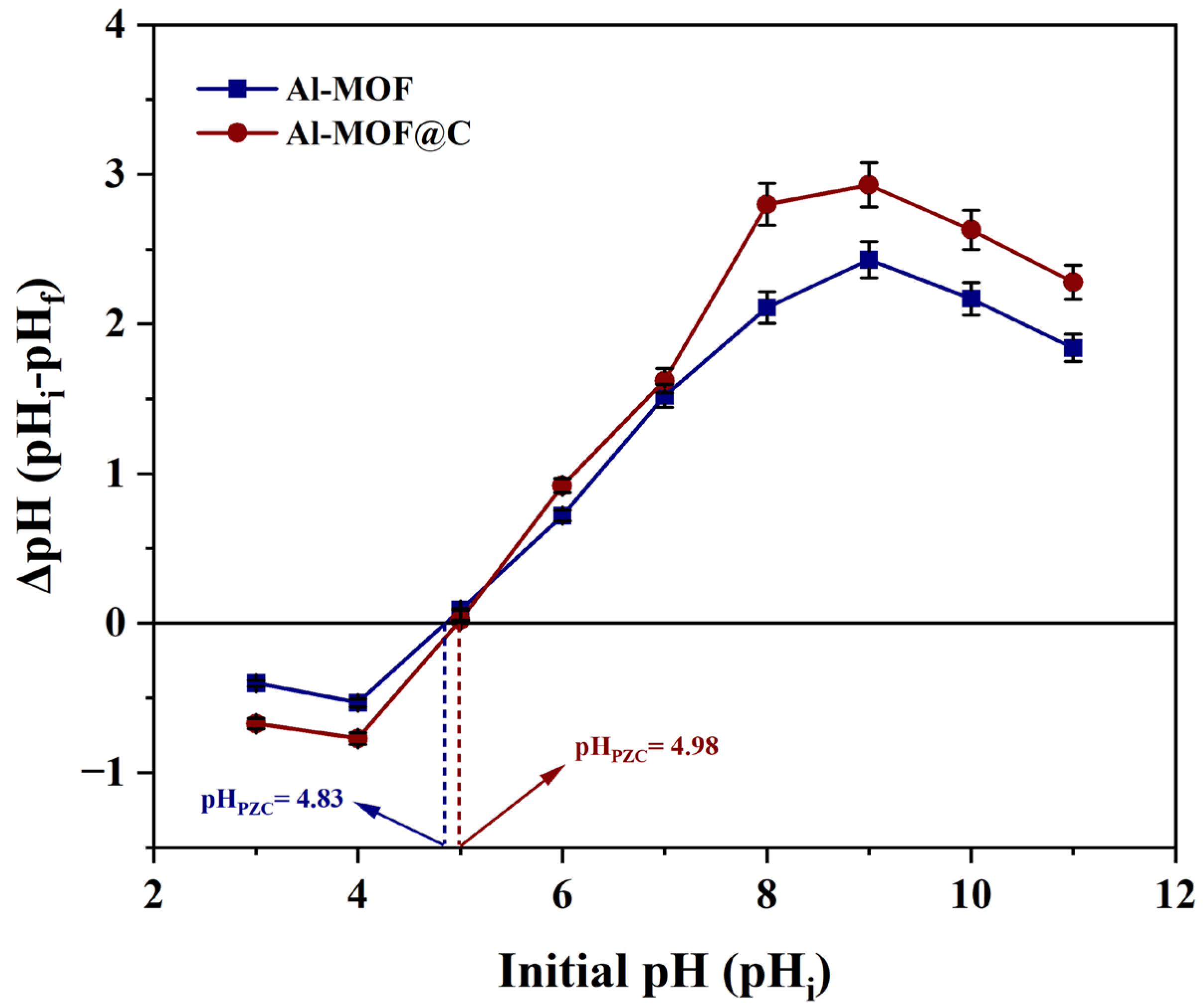

2.2.1. Study of Point of Zero Charge (PZC)

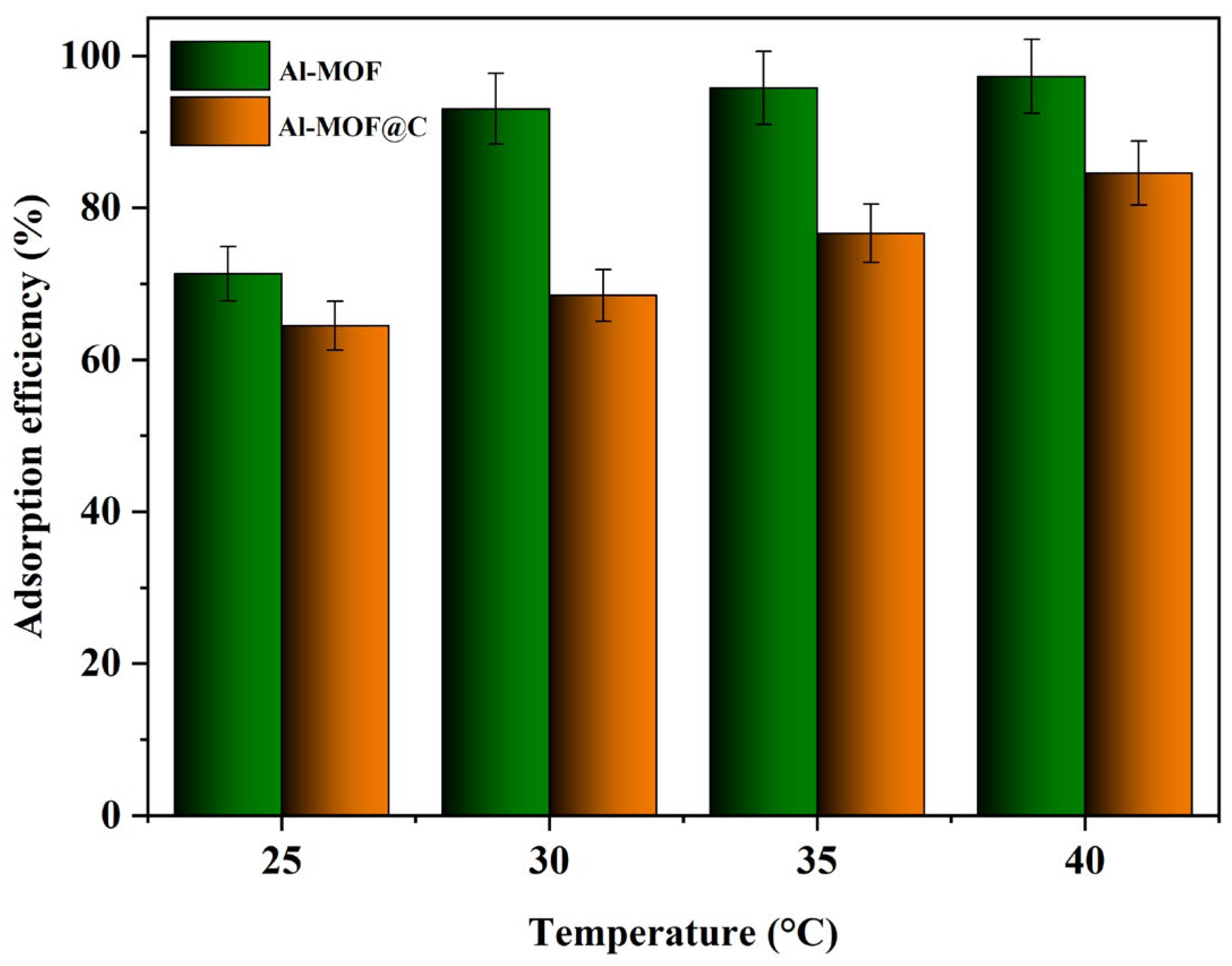

2.2.2. Effect of Temperature on Adsorption Process

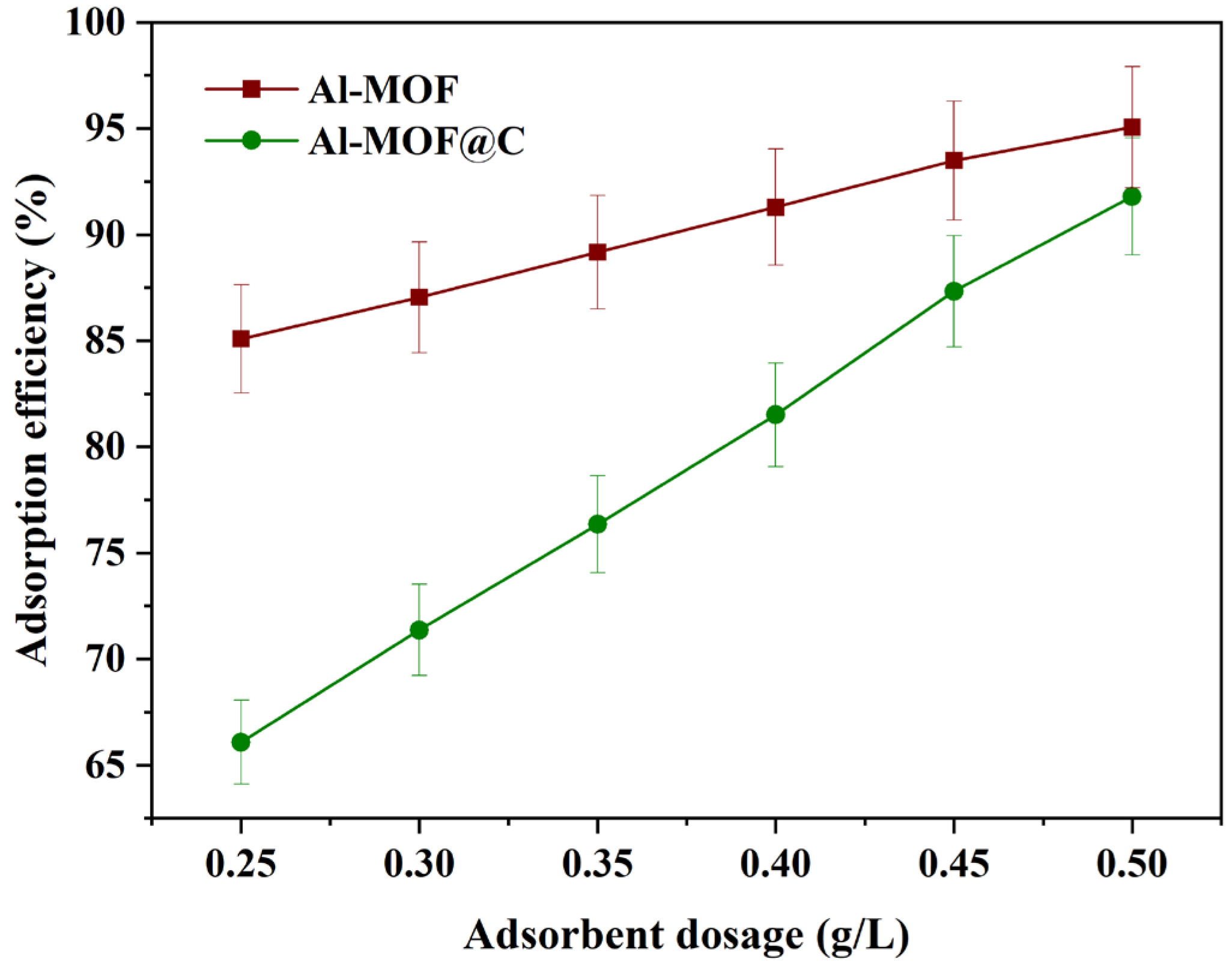

2.2.3. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage on Adsorption Process

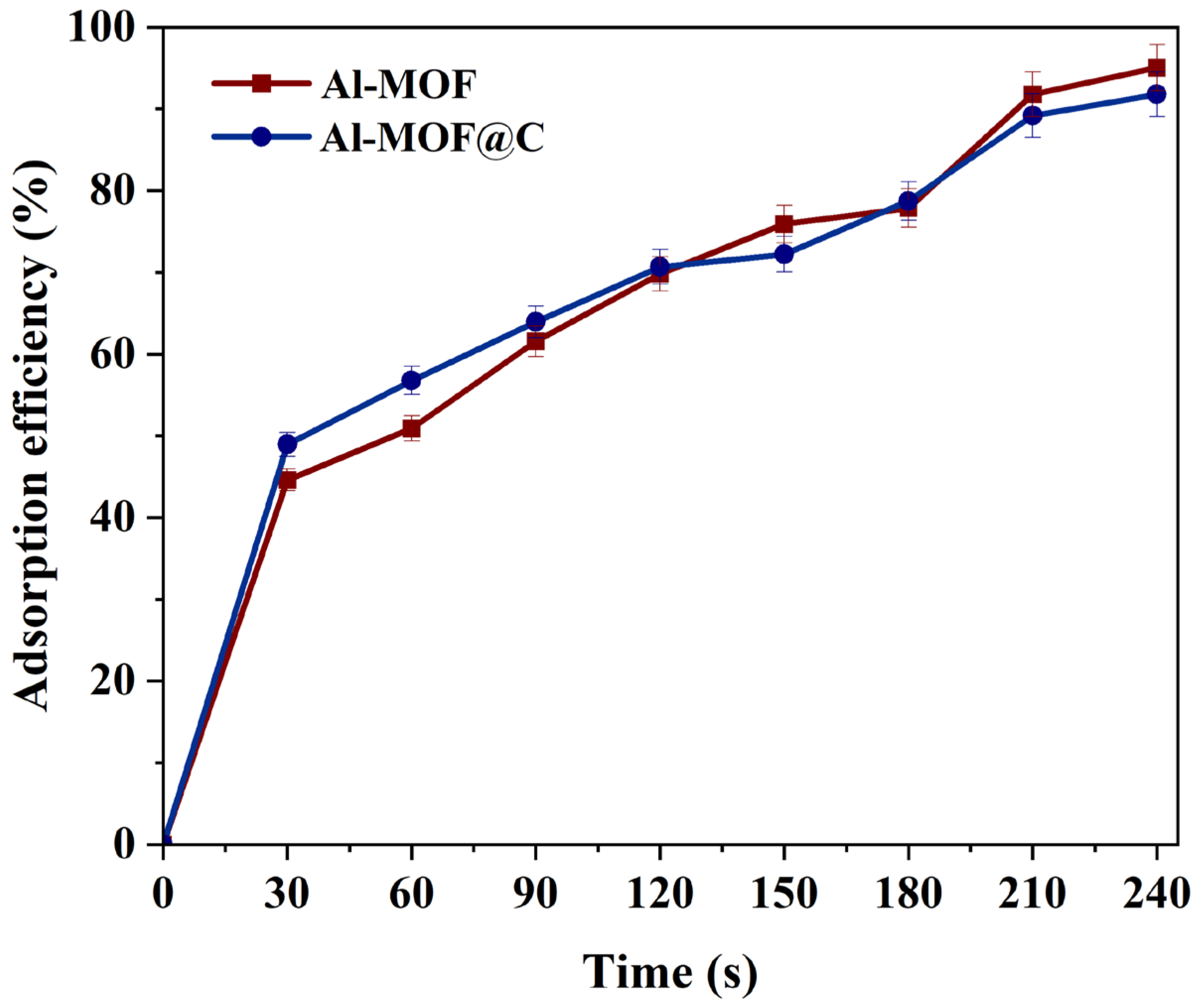

2.2.4. Effect of Time on Adsorption Process

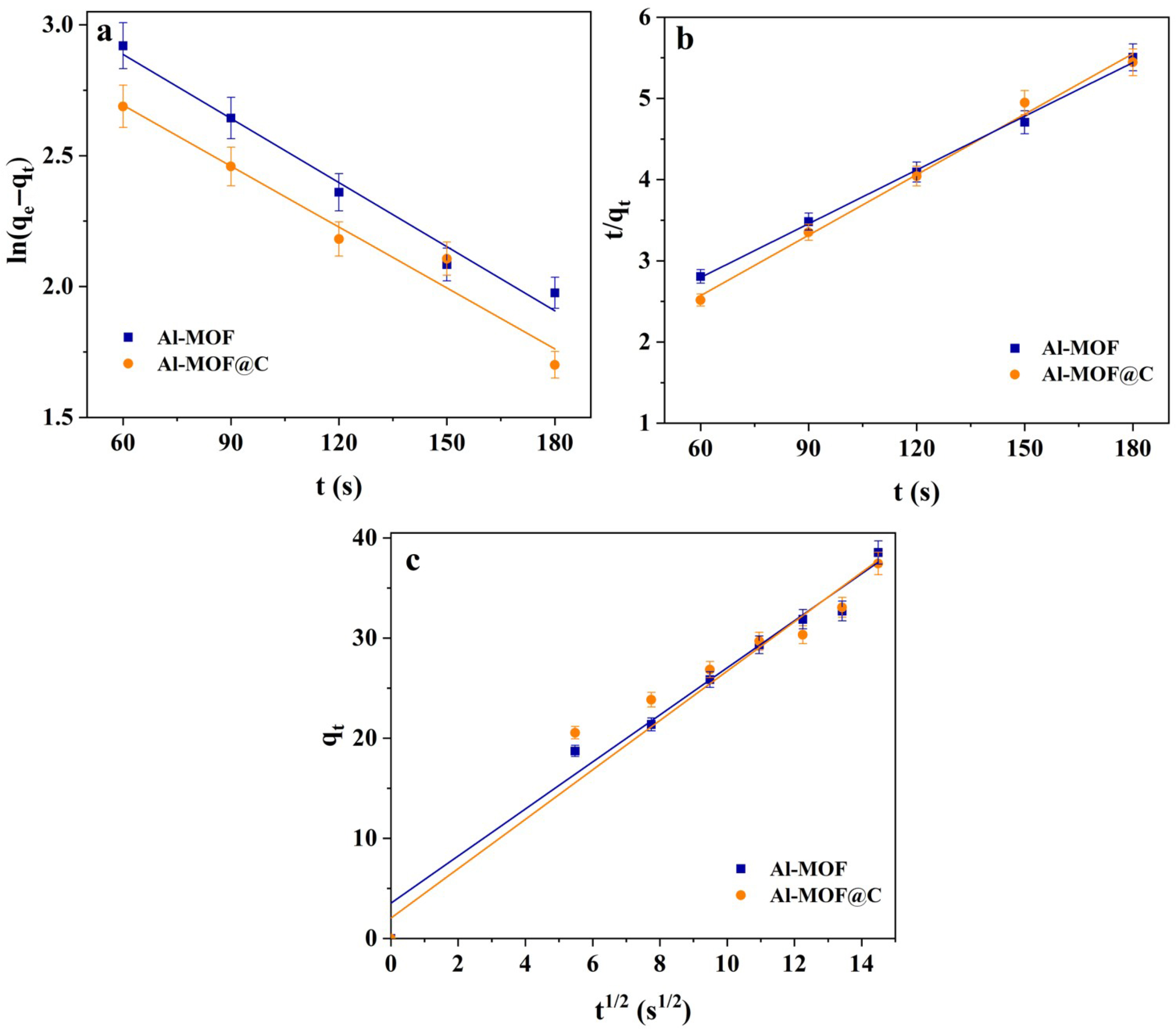

2.3. Kinetic Studies on Adsorption Behavior of CR Dye

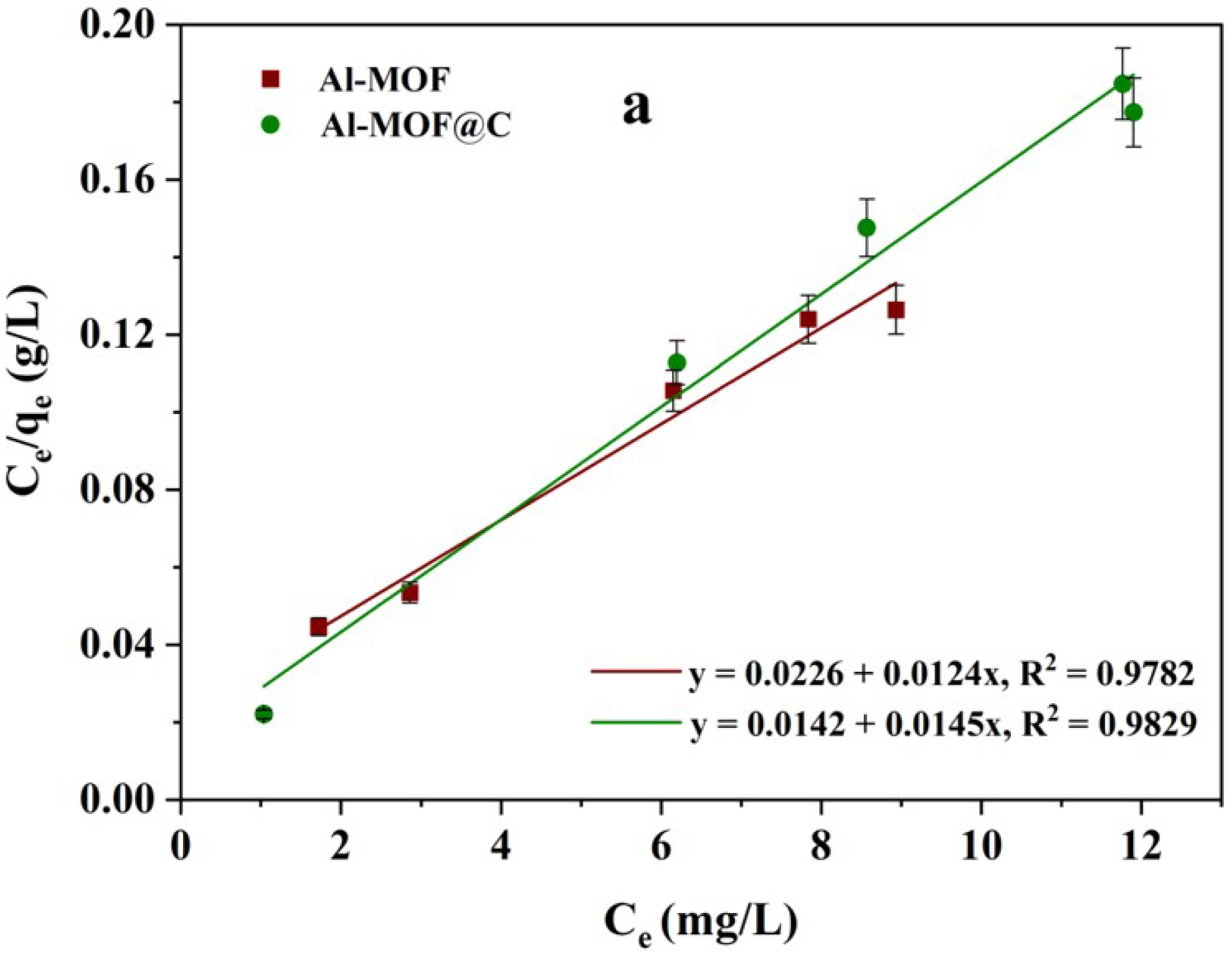

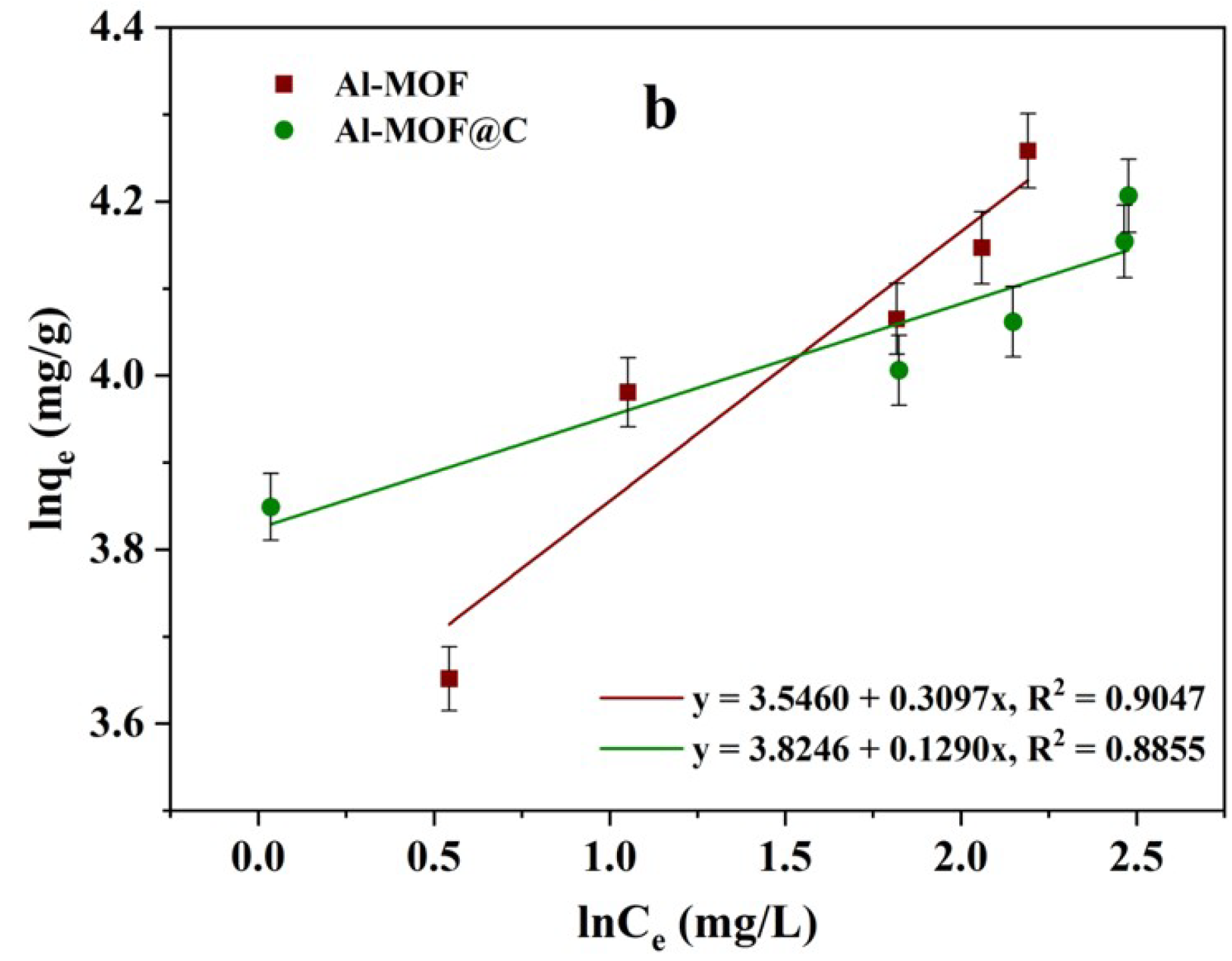

2.4. Isotherm Studies on Adsorption Behavior of CR Dye

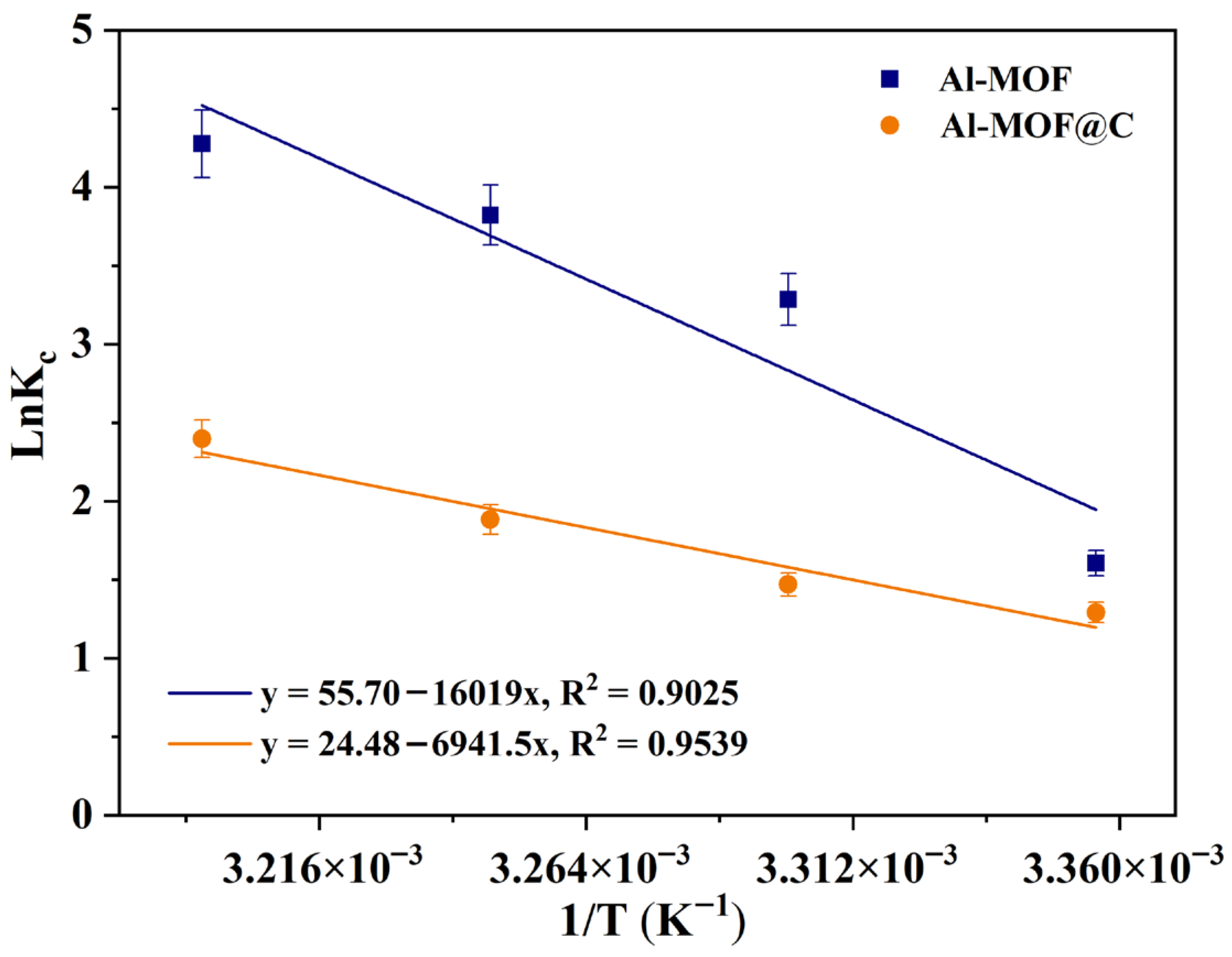

2.5. Thermodynamic Study

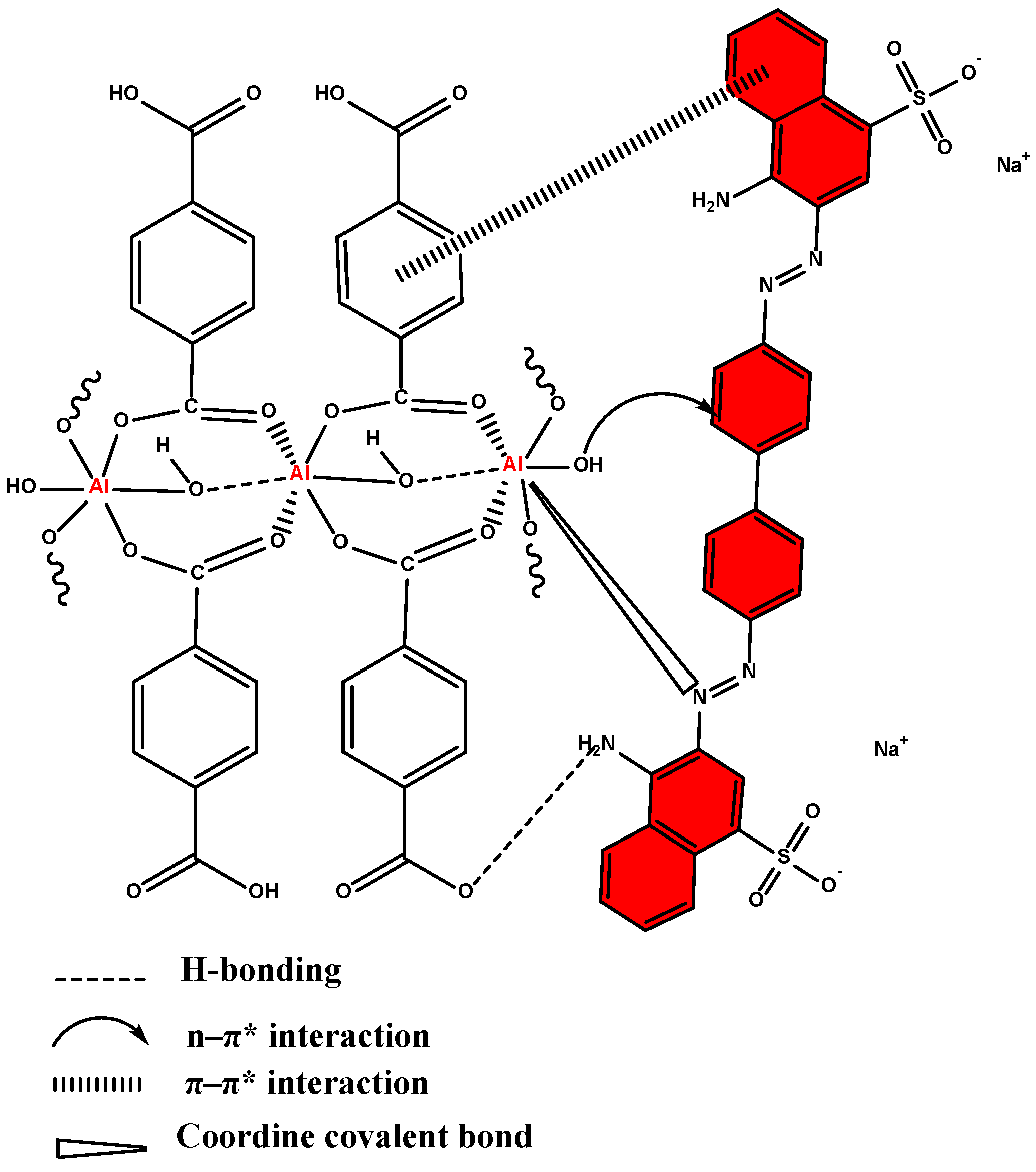

2.6. Possible Mechanism for Adsorption of CR onto Al-MOF and Al-MOF@C Adsorbents

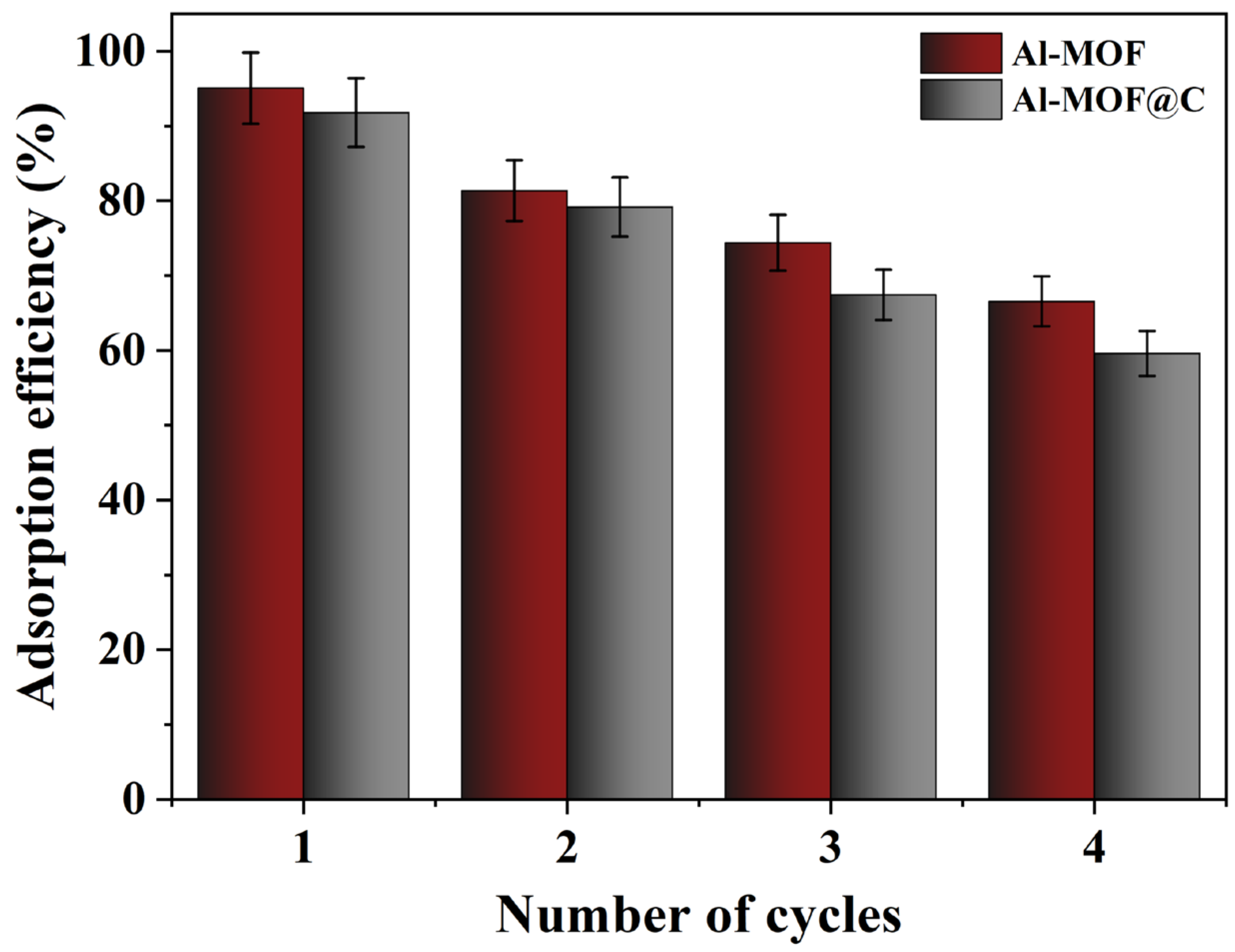

2.7. Reusability of Al-MOF and Al-MOF@C

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Instruments

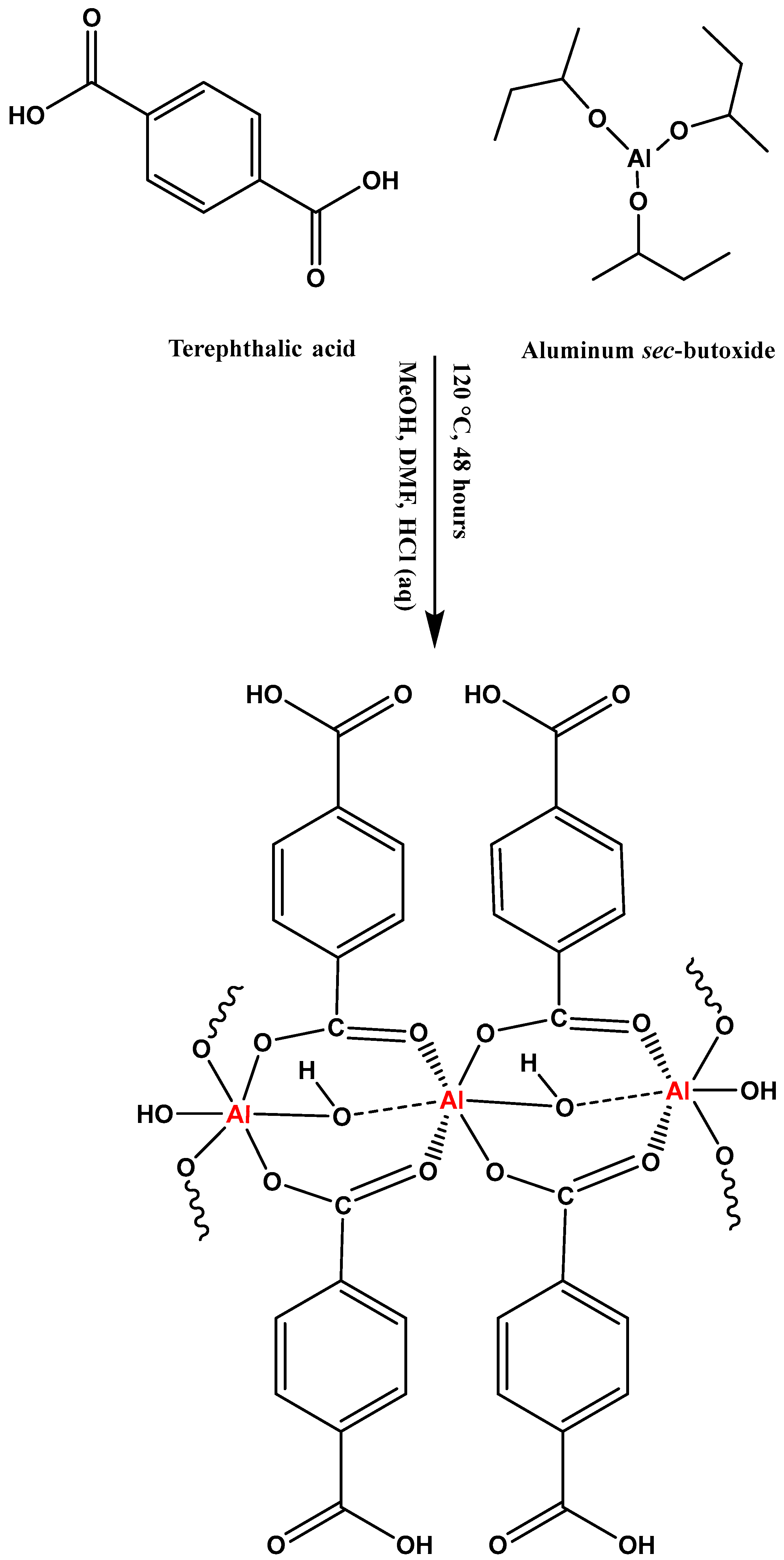

3.3. Synthesis of Al-MOF and Al-MOF@C

3.4. Adsorption Studies of Congo Red (CR) Dye

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, Y.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Song, G.; Sun, Y.; Ding, G. A review on selective dye adsorption by different meanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellis, B.; Fávaro-Polonio, C.Z.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2019, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.X.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Kang, Y.; Luo, J.W. Adsorption of congo red by cross-linked chitosan resins. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 7733–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Lee, M.W.; Wooa, S.H. Adsorption of congo red by chitosan hydrogel beads impregnated with carbon nanotubes. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1800–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Suhas. Application of low-cost adsorbents for dye removal—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2313–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayan, G.Ö.; Kayan, A. Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane and Polyorganosilicon Hybrid Materials and Their Usage in the Removal of Methylene Blue Dye. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2022, 32, 2781–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, J.; Lee, L.Y.; Hiew, B.Y.Z.; Thangalazhy-Gopakumar, S.; Lim, S.S.; Gan, S. Assessment of fish scales waste as a low cost and eco-friendly adsorbent for removal of an azo dye: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Sharma, P. Congo red dye adsorption onto cationic amino-modified walnut shell: Characterization, RSM optimization, isotherms, kinetics, and mechanism studies. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 21, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momina; Mohammad, S.; Suzylawati, I. Study of the adsorption/desorption of MB dye solution using bentonite adsorbent coating. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 34, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A.; Alene, A.N. A comparative study of acidic, basic, and reactive dyes adsorption from aqueous solution onto kaolin adsorbent: Effect of operating parameters, isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Emerg. Contam. 2022, 8, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N.N.A.; Jawad, A.H.; Ismail, K.; Razuan, R.; ALOthman, Z.A. Fly ash modified magnetic chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol blend for reactive orange 16 dye removal: Adsorption parametric optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, T.; Razzaq, A.; Javed, F.; Hafeez, A.; Rashid, N.; Amjad, U.S.; Ur Rehman, M.S.; Faisal, A.; Rehman, F. Integrating adsorption and photocatalysis: A cost effective strategy for textile wastewater treatment using hybrid biochar-TiO2 composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 121623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Mi, S.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Z. Enhanced dyes adsorption from wastewater via Fe3O4 nanoparticles functionalized activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, S.; Khalid, U.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Javed, T.; Ghani, A.; Naz, S.; Iqbal, M. ZnO, MgO and FeO adsorption efficiencies for direct sky Blue dye: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 5881–5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.; Jun, J.W.; Jhung, S.H. Adsorptive removal of methyl orange and methylene blue from aqueous solution with a metal-organic framework material, iron terephthalate (MOF-235). J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendar, A.; Özcan, E.; Yatmaz, H.C.; Zorlu, Y. Multifunctional Anionic Cyclotriphosphazene-Based Metal–Organic Framework Featuring a One-Dimensional Zn(II) Inorganic Building Unit for Selective Chemical Sensing and Efficient Photocatalytic Activity. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 6169–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.T.; Kayan, A. Advanced biopolymer-based Ti/Si-terephthalate hybrid materials for sustainable and efficient adsorption of the tetracycline antibiotic. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Xie, Y.; Pham, T.D.; Shetty, S.; Son, F.A.; Idrees, K.B.; Chen, Z.; Xie, H.; Liu, Y.; Snurr, R.Q.; et al. Creating Optimal Pockets in a Clathrochelate-Based Metal-Organic Framework for Gas Adsorption and Separation: Experimental and Computational Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3737–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarcı, D.; Erucar, I.; Yücesan, G.; Zorlu, Y. Cationic Metal-Organic Frameworks Synthesized from Cyclotetraphosphazene Linkers with Flexible Tentacles. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 7123–7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.M.; Yang, R.N.; Yang, B.C.; Quan, S.; Jiang, X. Effect of free carboxylic acid groups in UiO-66 analogues on the adsorption of dyes from water: Plausible mechanisms for adsorption and gate-opening behavior. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 283, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, O.K.; Eryazici, I.; Jeong, N.C.; Hauser, B.G.; Wilmer, C.E.; Sarjeant, A.A.; Snurr, R.Q.; Nguyen, S.T.; Yazaydin, A.Ö.; Hupp, J.T. Metal-organic framework materials with ultrahigh surface areas: Is the sky the limit. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15016–15021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Miao, J.; Yu, Y.; Fu, J.; Jia, B.; Li, L. Superparamagnetic Fe3O4@Al-based metal-organic framework nanocomposites with high-performance removal of Congo red. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhvalov, A. Aluminum metal–organic frameworks for sorption in solution: A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 374, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Qu, H. Efficient adsorption of dyes using polyethyleneimine-modified NH2-MIL-101(Al) and its sustainable application as a flame retardant for an epoxy resin. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 32286–32294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannert, N.; Ernst, S.J.; Jansen, C.; Bart, H.J.; Henninger, S.K.; Janiak, C. Evaluation of the highly stable metal-organic framework MIL-53(Al)-TDC (TDC = 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylate) as a new and promising adsorbent for heat transformation applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 17706–17712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahri, A.; El-Metwaly, N.M. Enhancing methyl violet 2B pollutant removal from wastewater using Al-MOF encapsulated with poly (itaconic acid) grafted crosslinked chitosan composite sponge: Synthesis, characterization, DFT calculation, adsorption optimization via Box-Behnken Design. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Heidenreich, N.; Lenzen, D.; Stock, N. Knoevenagel condensation reaction catalysed by Al-MOFs with CAU-1 and CAU-10-type structures. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 4187–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, K.; Wei, S.; Deyong, W. High-quality Al@Fe-MOF prepared using Fe-MOF as a micro-reactor to improve adsorption performance for selenite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanipoor, J.; Mohammadi, M.; Dinari, M.; Ehsani, M.R. Adsorption and Desorption of Amoxicillin Antibiotic from Water Matrices Using an Effective and Recyclable MIL-53(Al) Metal-Organic Framework Adsorbent. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2021, 66, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Xia, M.; Wang, X.; Cao, W.; Marchetti, A. Water-based preparation of nano-sized NH2-MIL-53(Al) frameworks for enhanced dye removal. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 484, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, E.; Lo, V.; Minett, A.I.; Harris, A.T.; Church, T.L. Dichotomous adsorption behaviour of dyes on an amino-functionalised metal-organic framework, amino-MIL-101(Al). J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, K.; Du, Q.; Wang, Y.; Pi, X.; et al. Efficient adsorption of Congo red by micro/nano MIL-88A (Fe, Al, Fe-Al)/chitosan composite sponge: Preparation, characterization, and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, V.; Uthappa, U.T.; Arvind Swami, O.R.; Han, S.S.; Jung, H.Y.; Altalhi, T.; Kurkuri, M.D. Sustainable green functional nano aluminium fumarate-MOF decorated on 3D low-cost natural diatoms for the removal of Congo red dye and fabric whitening agent from wastewater: Batch & continuous adsorption process. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, G.V.; Baig, M.T.; Kayan, A. UiO-66 MOF/Zr-di-terephthalate/cellulose hybrid composite synthesized via sol-gel approach for the efficient removal of methylene blue dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langseth, E.; Swang, O.; Arstad, B.; Lind, A.; Cavka, J.H.; Jensen, T.L.; Kristensen, T.E.; Moxnes, J.; Unneberg, E.; Heyn, R.H. Synthesis and characterization of Al@MOF materials. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 226, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cao, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Song, P.; Jia, M.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, X. Heterogeneous activation of peroxymonosulfate by cobalt-doped MIL-53(Al) for efficient tetracycline degradation in water: Coexistence of radical and non-radical reactions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 581, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C. The Strengthening Role of the Amino Group in Metal–Organic Framework MIL-53 (Al) for Methylene Blue and Malachite Green Dye Adsorption. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2015, 60, 3414–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mel’gunov, M.S. Application of the simple Bayesian classifier for the N2 (77 K) adsorption/desorption hysteresis loop recognition. Adsorption 2023, 29, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Du, Q.; Song, F.; Chen, B.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; et al. Efficient adsorption of azo anionic dye Congo Red by micro-nano metal-organic framework MIL-68 (Fe) and MIL-68 (Fe)/chitosan composite sponge: Preparation, characterization and adsorption performance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, C.; Pendar, A.; Zorlu, Y.; Davarcı, D. Selective Adsorption of Anionic Dyes Using New Three-Dimension Ag (I) Coordination Polymer. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 8031–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Du, Q.; Pi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Efficient removal of Congo red in water by in-situ immobilization of amino-functionalized UiO-67-NH2 on cellulose aerogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 328, 147630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaweil, A.S.; Mamdouh, I.M.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; El-Subruiti, G.M. Highly Efficient Removal for Methylene Blue and Cu2+ onto UiO-66 Metal–Organic Framework/Carboxylated Graphene Oxide-Incorporated Sodium Alginate Beads. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 23528–23541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, A.; Aziz, A.A.A.; Abdel-aziz, A.M.; Sidqi, M.E.; Sayed, M.A. Harnessing synergistic effect of Al and Zn in novel bimetallic MOF for superior environmental pollutants adsorption. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 179, 114870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalafi, M.H. Sustainable biopolymer-supported Ce-MOF/polyethyleneimine-guar gum composite sponge for efficient removal of ketoprofen from water: Design, mechanism, and optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 331, 148356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Le, Y.; Cheng, B. Fabrication of porous ZrO2 hollow sphere and its adsorption performance to Congo red in water. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 10847–10856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, L.; Thi, N.; Nguyen, T.; Thi, T.; Nguyen, T. Facile synthesis of CoFe2O4@ MIL–53(Al) nanocomposite for fast dye removal: Adsorption models, optimization and recyclability. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Kerdari, H.; Rabbani, M.; Sha, M. Synthesis, characterization and adsorbing properties of hollow Zn-Fe2O4 nanospheres on removal of Congo red from aqueous solution. Desalination 2011, 280, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, I.H.; Al-Sudani, F.T.; AbdulRazak, A.A.; Aldahri, T.; Rohani, S. Optimization of Congo red dye adsorption from wastewater by a modified commercial zeolite catalyst using response surface modeling approach. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Zaidi, S.; Aslam, A.; Khan, P.; Arish, M.; Khan, A.Y.; Tariq, M.; Chani, S.; Asiri, A.M. Removal of congo red from water by adsorption onto activated carbon derived from waste black cardamom peels and machine learning modeling. Alexandria Eng. J. 2023, 71, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, I.M.; Al-ghamdi, Y.O.; Darwesh, R.; Omaish, M.; Kashif, M. Properties and application of MoS2 nanopowder: Characterization, Congo red dye adsorption, and optimization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, D.; Ye, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, D.; Wu, D. Highly efficient and targeted adsorption of Congo Red in a novel cationic copper-organic framework with three-dimensional cages. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 329, 125149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Baeyens, J. Adsorption of Congo red dye on FexCo3-xO4 nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xia, L. Highly enhanced adsorption of congo red onto graphene oxide/chitosan fibers by wet-chemical etching off silica nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 245, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, K.M.; Palanisamy, P.N.; Kowshalya, V.N.; Tamilvanan, A.; Prabakaran, R.; Kim, S.C. Uncalcined Zn/Al Carbonate LDH and Its Calcined Counterpart for Treating the Wastewater Containing Anionic Congo Red Dye. Energies 2024, 17, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdari, R.; Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Bahrani, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Decorated graphene with aluminum fumarate metal organic framework as a superior non-toxic agent for efficient removal of Congo Red dye from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essam, R.; Abdel-Hafeez, S.R.; EL-Rabiei, M.M.; Burham, N.; El-Shahat, M.F.; Radwan, A. Harnessing Temperature-Dependent Breathing Behaviour in Aluminium-Based MOF for Enhanced Congo Red Dye Removal. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 39, e70135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lyu, J.; Bai, P. One-step synthesis of Al-doped UiO-66 nanoparticle for enhanced removal of organic dyes from wastewater. Molecules 2023, 28, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Al-MOF | Al-MOF@C | |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Area (SA, m2/g) | ||

| Multipoint BET | 563.9 | 487.1 |

| BJH MC Adsorption SA | 548.3 | 473.7 |

| BJH MC Desorption SA | 481.1 | 410.1 |

| DH MC Adsorption SA | 573.1 | 505.6 |

| DH MC Desorption SA | 495.4 | 423.3 |

| DR M Micro Pore Area | 693.0 | 602.9 |

| Pore Volume (PV, cm3/g) | ||

| BJH MC Adsorption PV | 0.5970 | 0.3890 |

| BJH MC Desorption PV | 0.5712 | 0.3697 |

| DH MC Adsorption PV | 0.5843 | 0.3848 |

| DH MC Desorption PV | 0.5579 | 0.3628 |

| Pore Size or Diameter (PD, Å) | ||

| BJH M Adsorption PD | 10.03 | 10.01 |

| BJH M Desorption PD | 10.14 | 10.17 |

| DH M Adsorption PD | 10.03 | 10.01 |

| DH M Desorption PD | 10.14 | 10.17 |

| Kinetic Model | Parameters | Al-MOF | Al-MOF@C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental qe (mg/g) | 39.90 | 38.53 | ||

| Pseudo-first-order | k1 | (1/s) | 0.0082 | 0.0078 |

| qe | (mg/g) | 29.24 | 23.51 | |

| R2 | 0.9806 | 0.9672 | ||

| Pseudo-second-order | k2 | (g/mg·min) | 0.00033 | 0.00056 |

| qe | (mg/g) | 45.24 | 40.32 | |

| R2 | 0.9975 | 0.9936 | ||

| Intraparticle diffusion | k3 | (mg/g·s1/2) | 2.4651 | 2.3484 |

| C | (mg/g) | 2.048 | 3.5474 | |

| R2 | 0.9786 | 0.9529 | ||

| Isotherm Model | Parameters | Al-MOF | Al-MOF@C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir Isotherm | qm (mg/g) | 80.64 | 68.96 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.548 | 1.021 | |

| RL | 0.080 | 0.038 | |

| R2 | 0.9782 | 0.9829 | |

| Freundlich Isotherm | nf | 3.22 | 7.75 |

| Kf (mg/g)(L/mg)(1/nf) | 34.67 | 45.81 | |

| R2 | 0.9047 | 0.8855 |

| Adsorbent | Parameters | Temperature (K) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298.15 | 303.15 | 308.15 | 313.15 | ||

| Al-MOF | ΔG° (kJ/mol) | −3.97 | −8.28 | −9.79 | −11.13 |

| ΔS° (kJ/mol K) | 0.463 | ||||

| ΔH° (kJ/mol) | 133.18 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9025 | ||||

| Al-MOF@C | ΔG° (kJ/mol) | −3.19 | −3.70 | −4.82 | −6.24 |

| ΔS° (kJ/mol K) | 0.203 | ||||

| ΔH° (kJ/mol) | 57.71 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9539 | ||||

| Adsorbent | Adsorption Capacity (qmax, from Langmuir, mg/g) | pH | Temp (°C) | Time | Kinetic Model | Isotherm | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrO2 reagent | 4.80 | 7 | 30 | 24 h | PSO | L | [45] |

| MIL–53(Al) | 15.29 | 4 | 30 | 30 min | E | T | [46] |

| Hollow ZnFe2O4 nanospheres | 16.58 | 6 | 25 | 120 min | - | L | [47] |

| CoFe2O4 | 17.98 | 6 | 30 | 180 min | B | T | [46] |

| Modified Zeolite A | 21.11 | 7 | 24 | 90 min | PSO | T | [48] |

| CoFe2O4@MIL–53 (Al) | 43.77 | 6 | 30 | 10 min | B | T | [46] |

| ZrO2 hollow spheres | 59.50 | 7 | 30 | 24 h | PSO | L | [45] |

| Black Cardamom Activated Carbon | 69.93 | 6 | 30 | 120 min | PSO | L | [49] |

| MoS2-NP | 80.64 | 3 | 50 | 180 min | PSO | L | [50] |

| Cu-MOF | 119.76 | 7 | 25 | 300 s | PSO | L | [51] |

| FexCo3−xO4 nanoparticles | 160.30 | - | 25 | 240 min | PFO | L | [52] |

| Graphene oxide/Chitosan Fibers | 294.12 | 3 | 20 | 1500 min | PFO | L | [53] |

| Zn/Al carbonate-LDH | 526.32 | 6 | 30 | 90 min | PSO | F | [54] |

| DE-Fumarate-Al-MOF | 181.82 | 7 | 25 | 15 min | PSO | L | [33] |

| Fumarate-Al-MOF/GO | 132.80 | 8 | 25 | 30 min | PSO | L | [55] |

| Al-MOF from AlCl3 | 40.00 | 7 | 30 | 200 min | PSO | L | [56] |

| Al-MOF from AlCl3 | 118.60 | 7 | 40 | 200 min | PSO | L | [56] |

| Al-MOF | 80.64 | 7 | 25 | 240 s | PSO | L | This work |

| Al-MOF@C | 68.96 | 7 | 25 | 240 s | PSO | L | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duyar, C.; Kayan, A. Synthesis of Aluminum-Based MOF and Cellulose-Modified Al-MOF for Enhanced Adsorption of Congo Red Dye. Inorganics 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010006

Duyar C, Kayan A. Synthesis of Aluminum-Based MOF and Cellulose-Modified Al-MOF for Enhanced Adsorption of Congo Red Dye. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuyar, Ceyda, and Asgar Kayan. 2026. "Synthesis of Aluminum-Based MOF and Cellulose-Modified Al-MOF for Enhanced Adsorption of Congo Red Dye" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010006

APA StyleDuyar, C., & Kayan, A. (2026). Synthesis of Aluminum-Based MOF and Cellulose-Modified Al-MOF for Enhanced Adsorption of Congo Red Dye. Inorganics, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010006