Reactions of Benzylsilicon Pyridine-2-olate BnSi(pyO)3 and Selected Electrophiles—PhCHO, CuCl, and AgOTos

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

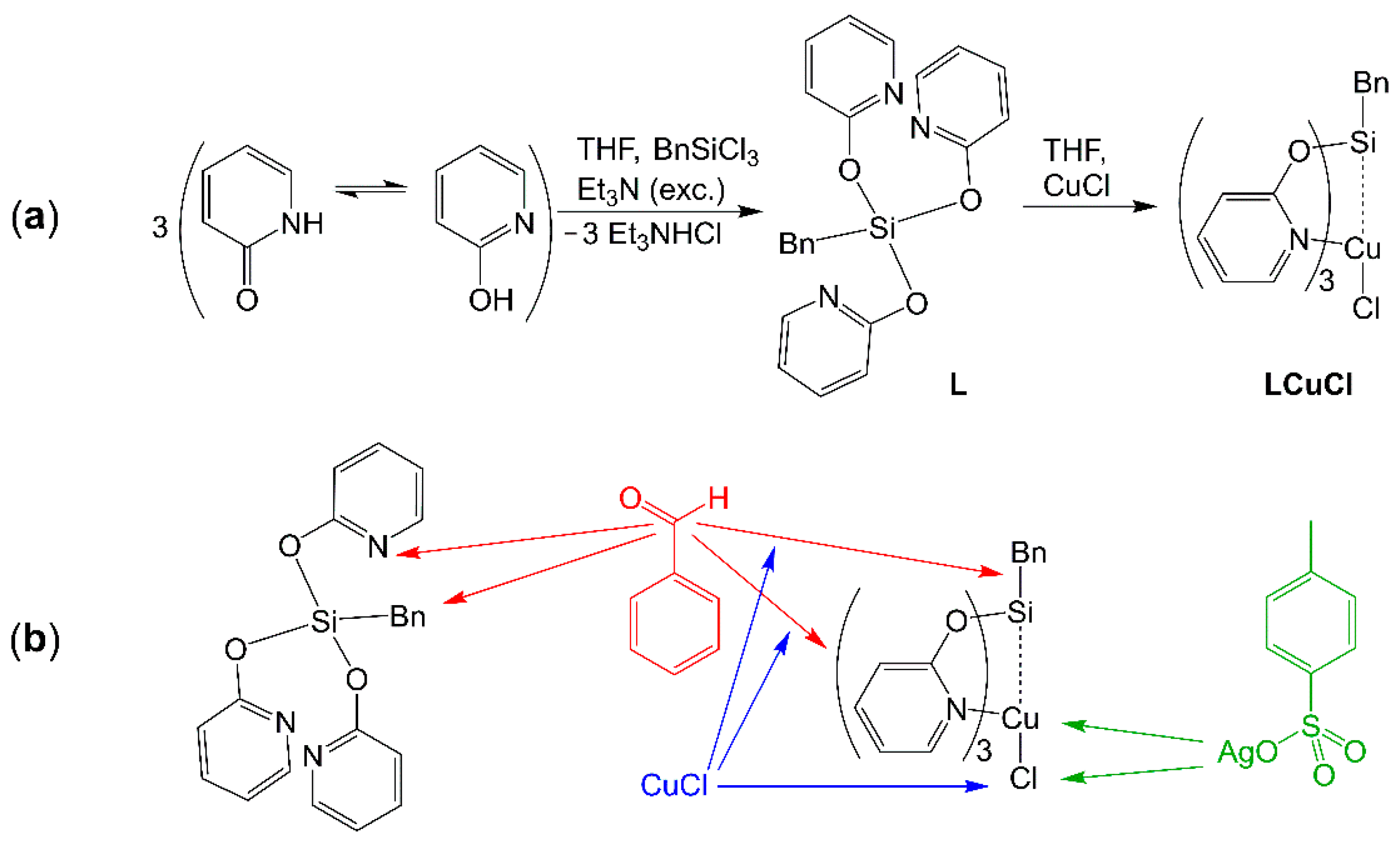

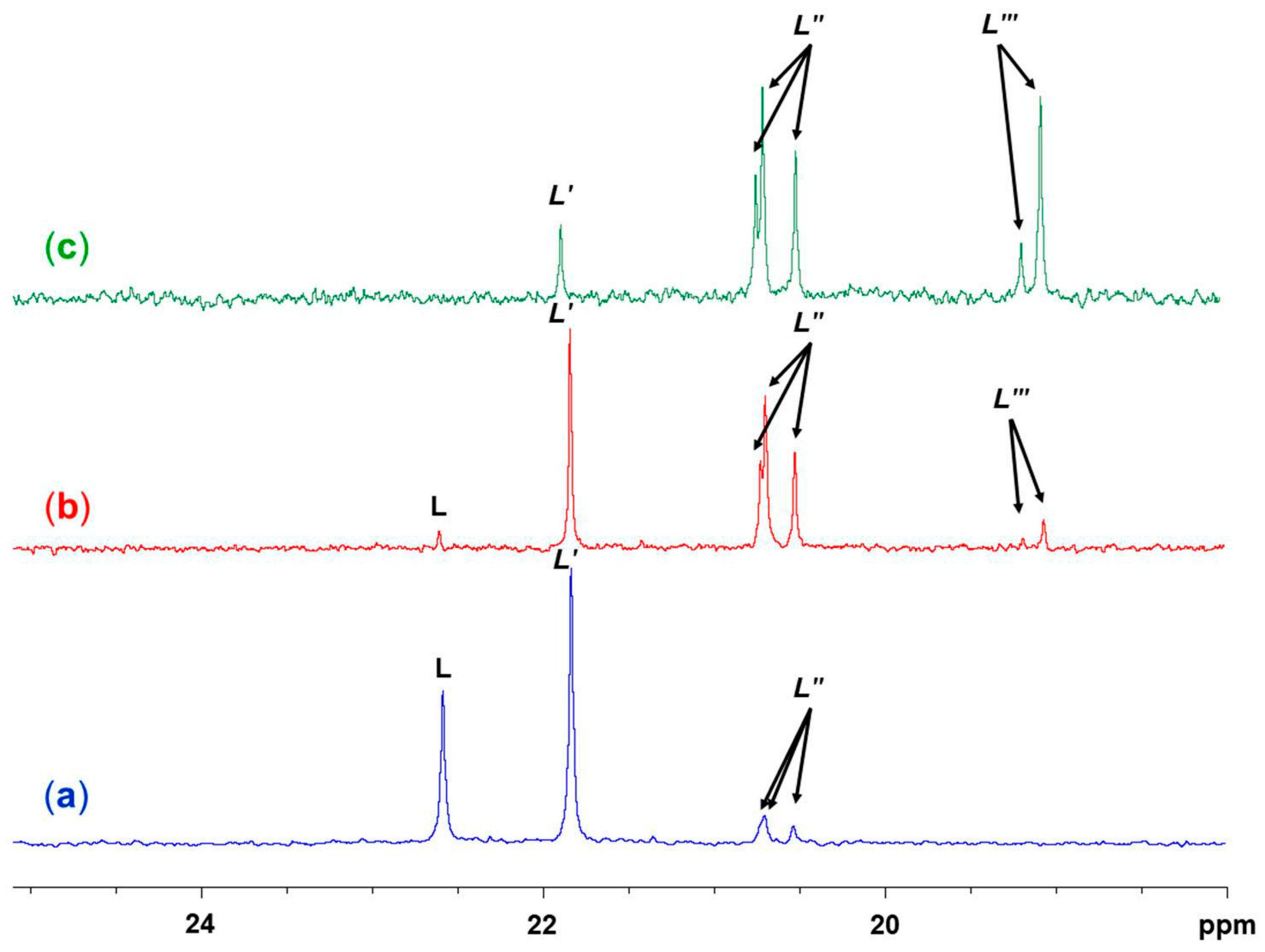

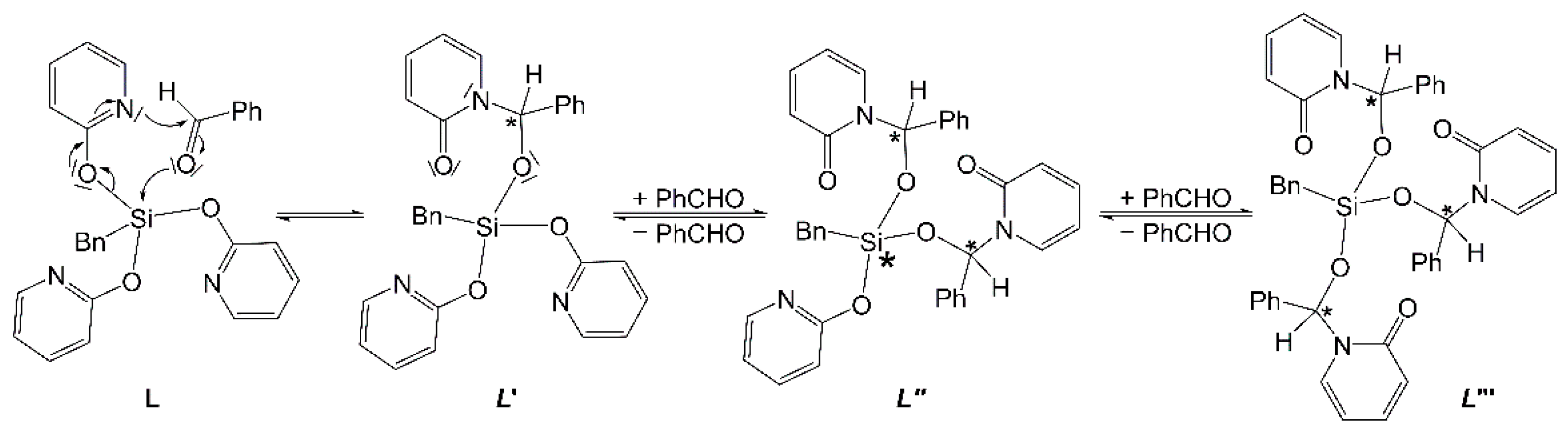

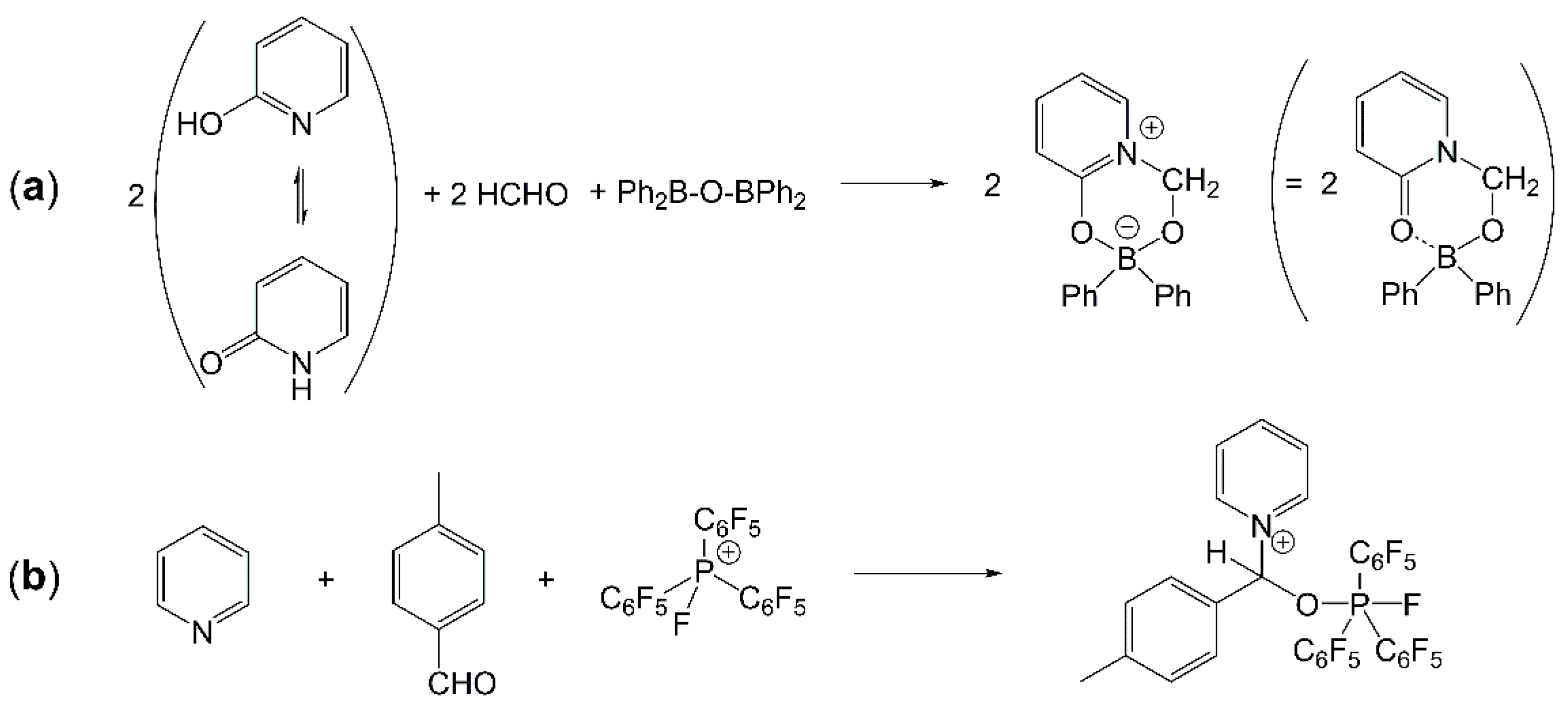

2.1. Reaction of Benzyltris(2-pyridyloxy)silane (Ligand L) and Benzaldehyde

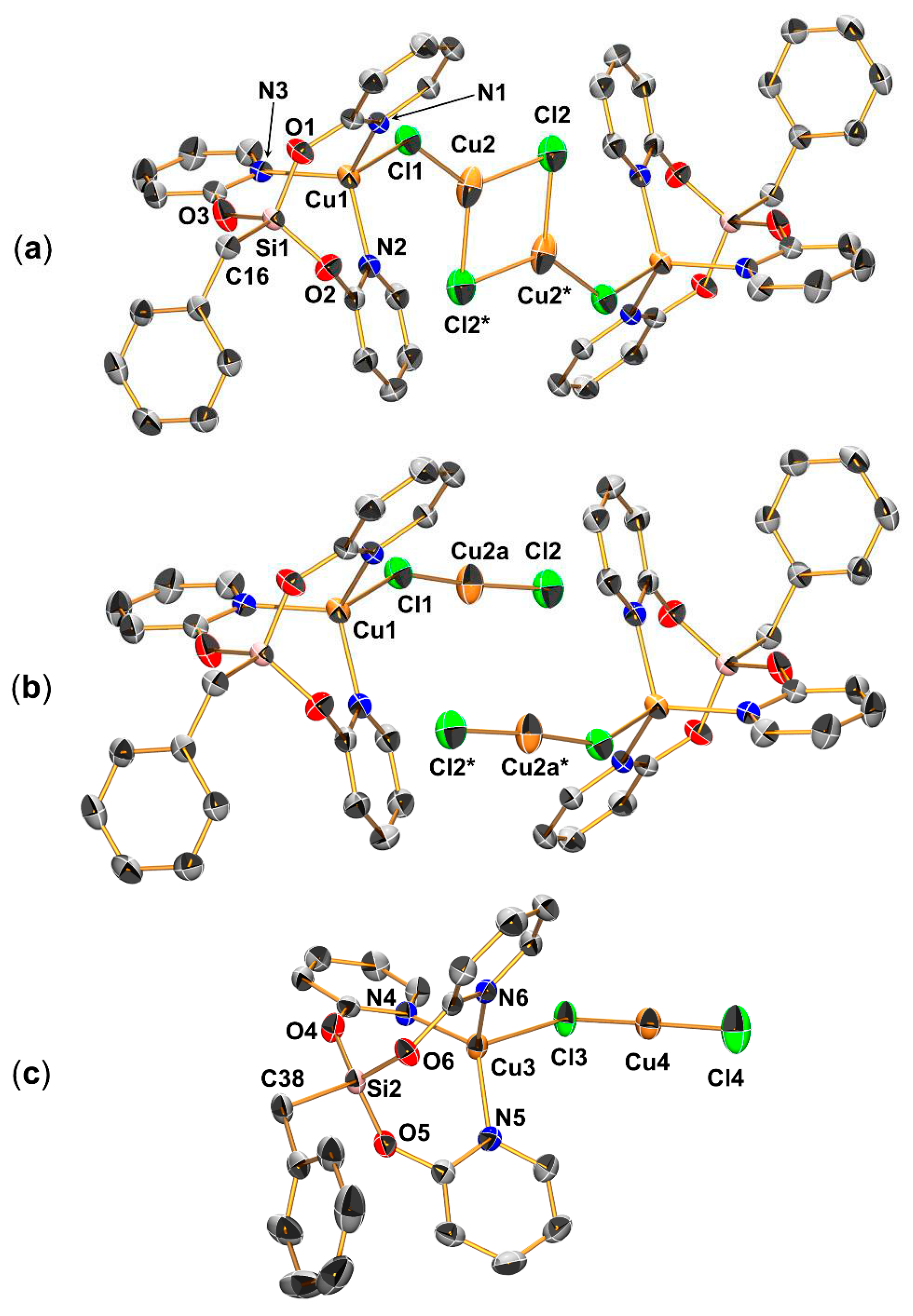

2.2. Reaction of Benzyltris(2-pyridyloxy)silane (L), Benzaldehyde and CuCl

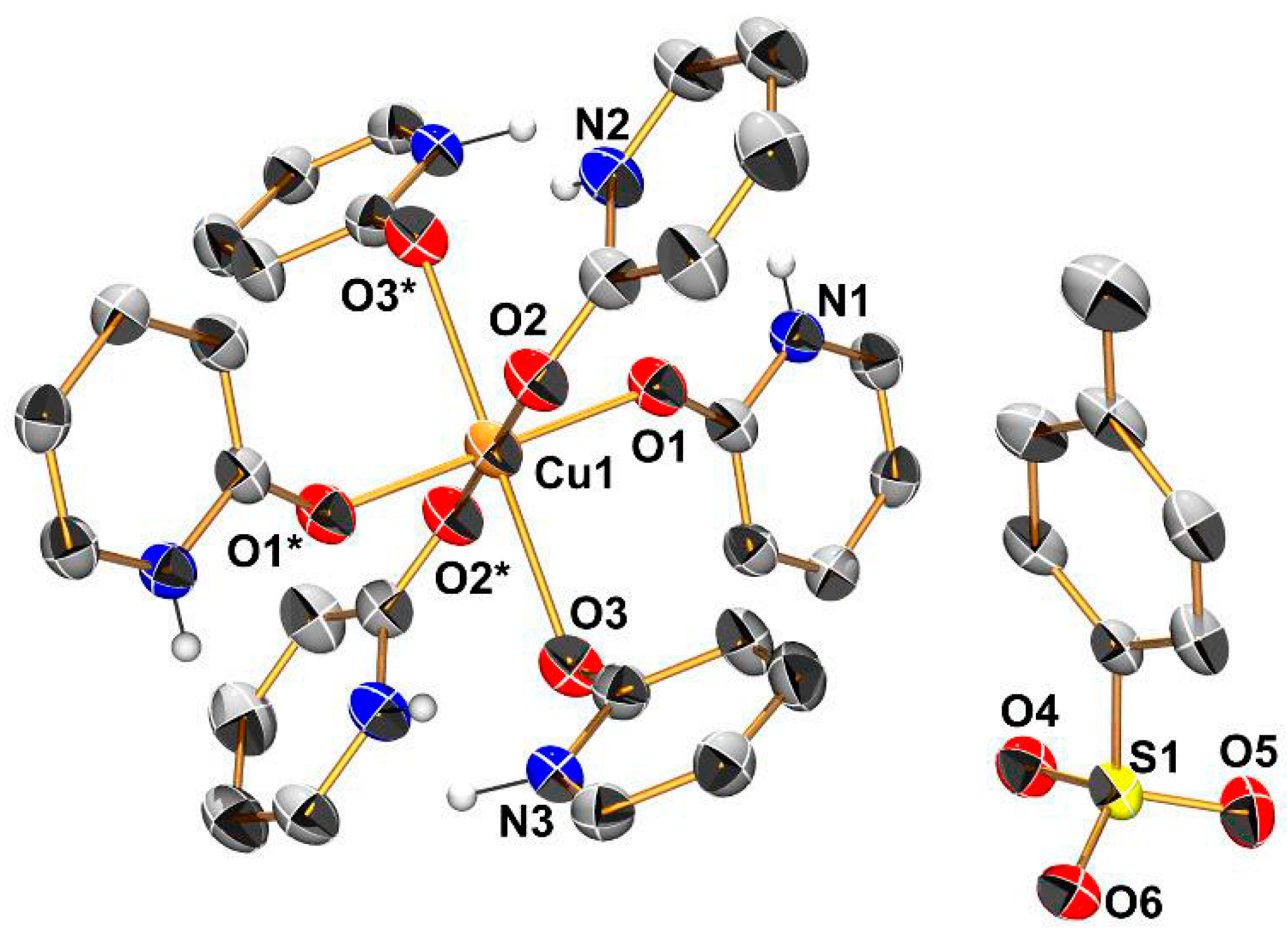

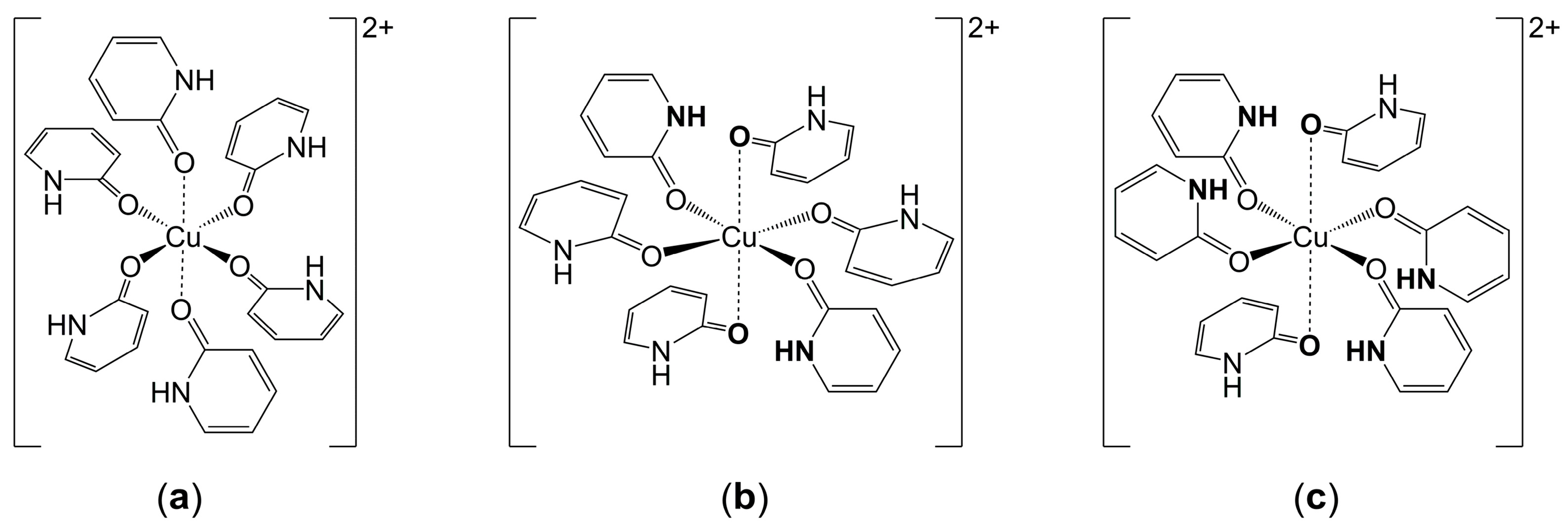

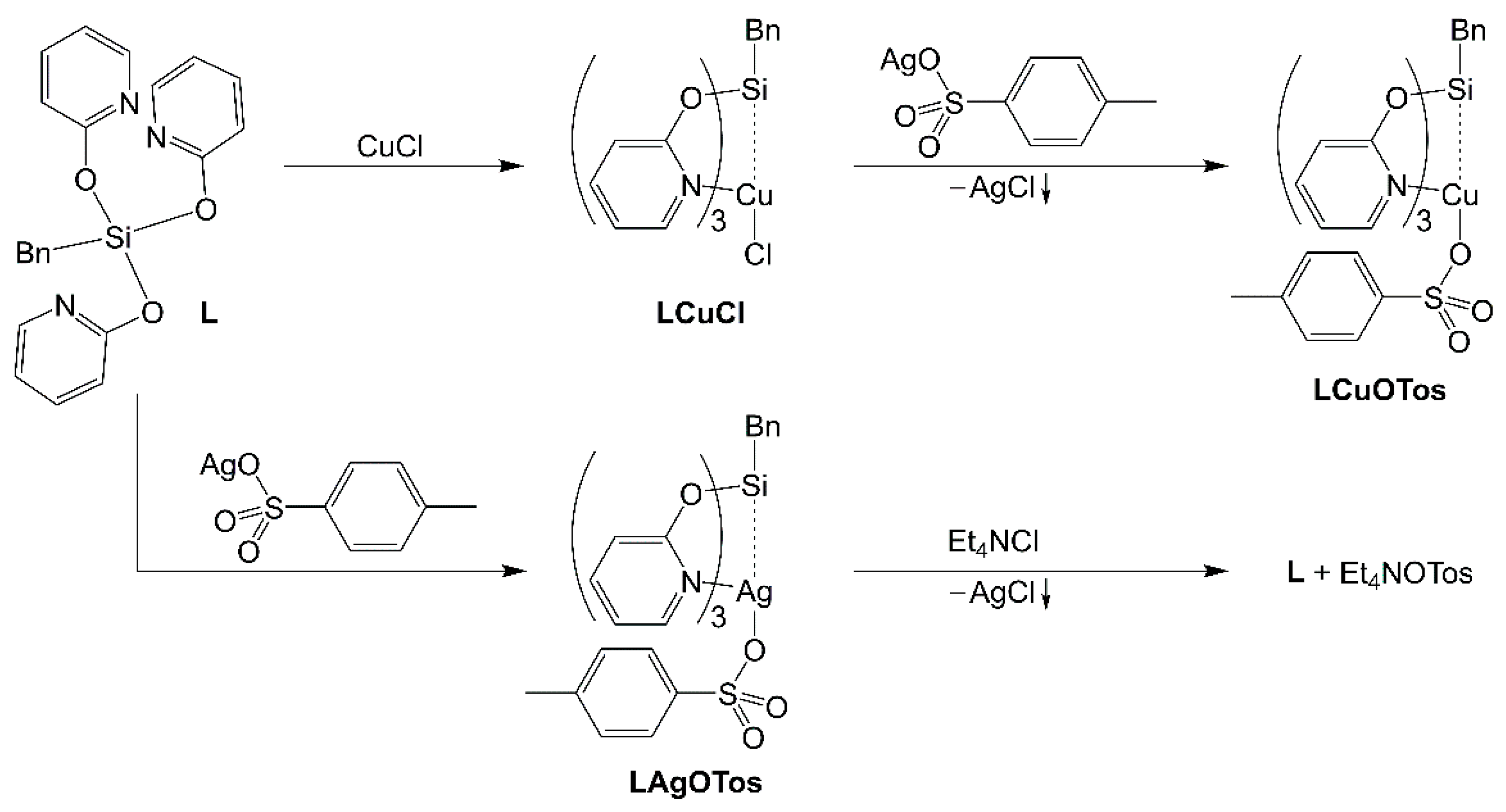

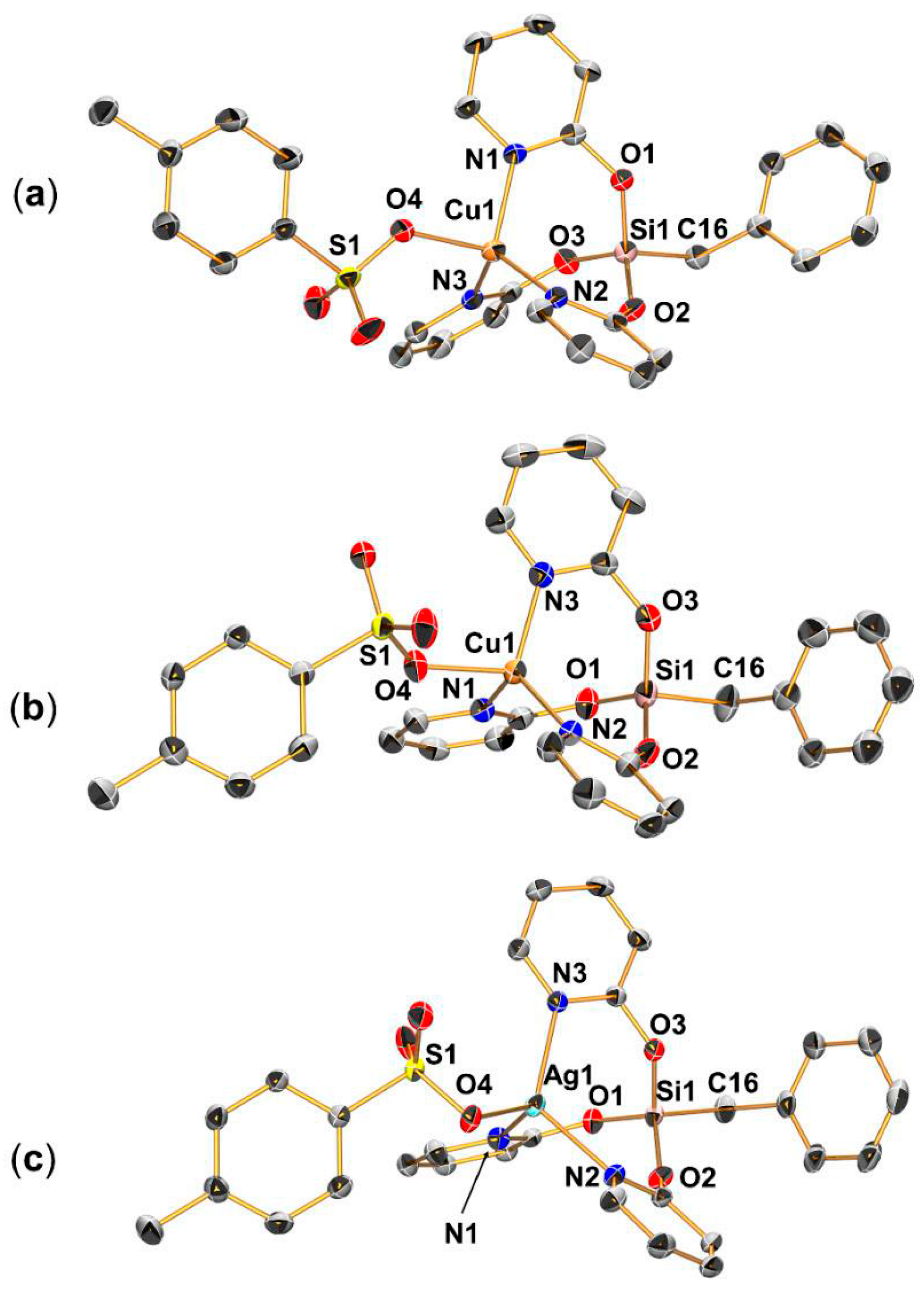

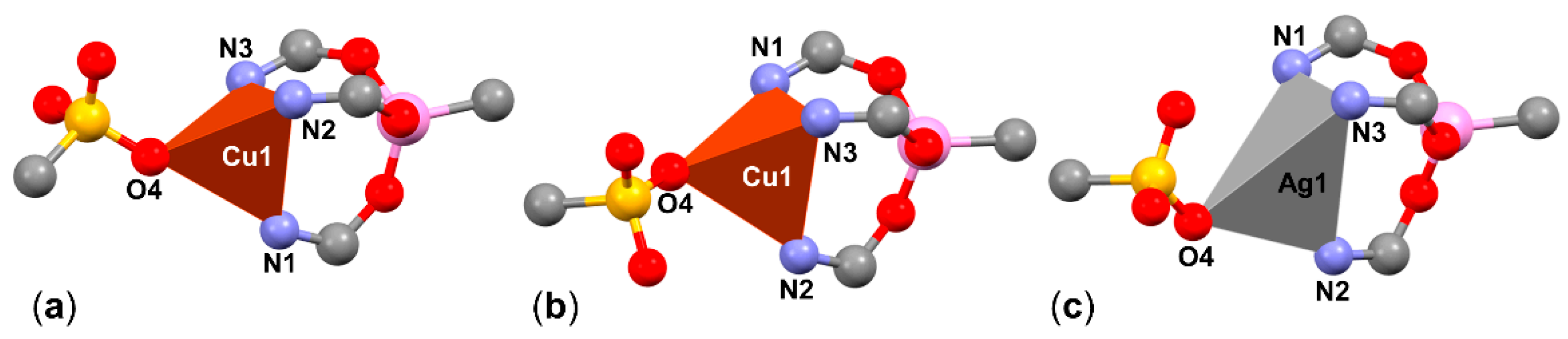

2.3. Syntheses and Molecular Structures of the Tosylates LCuOTos and LAgOTos

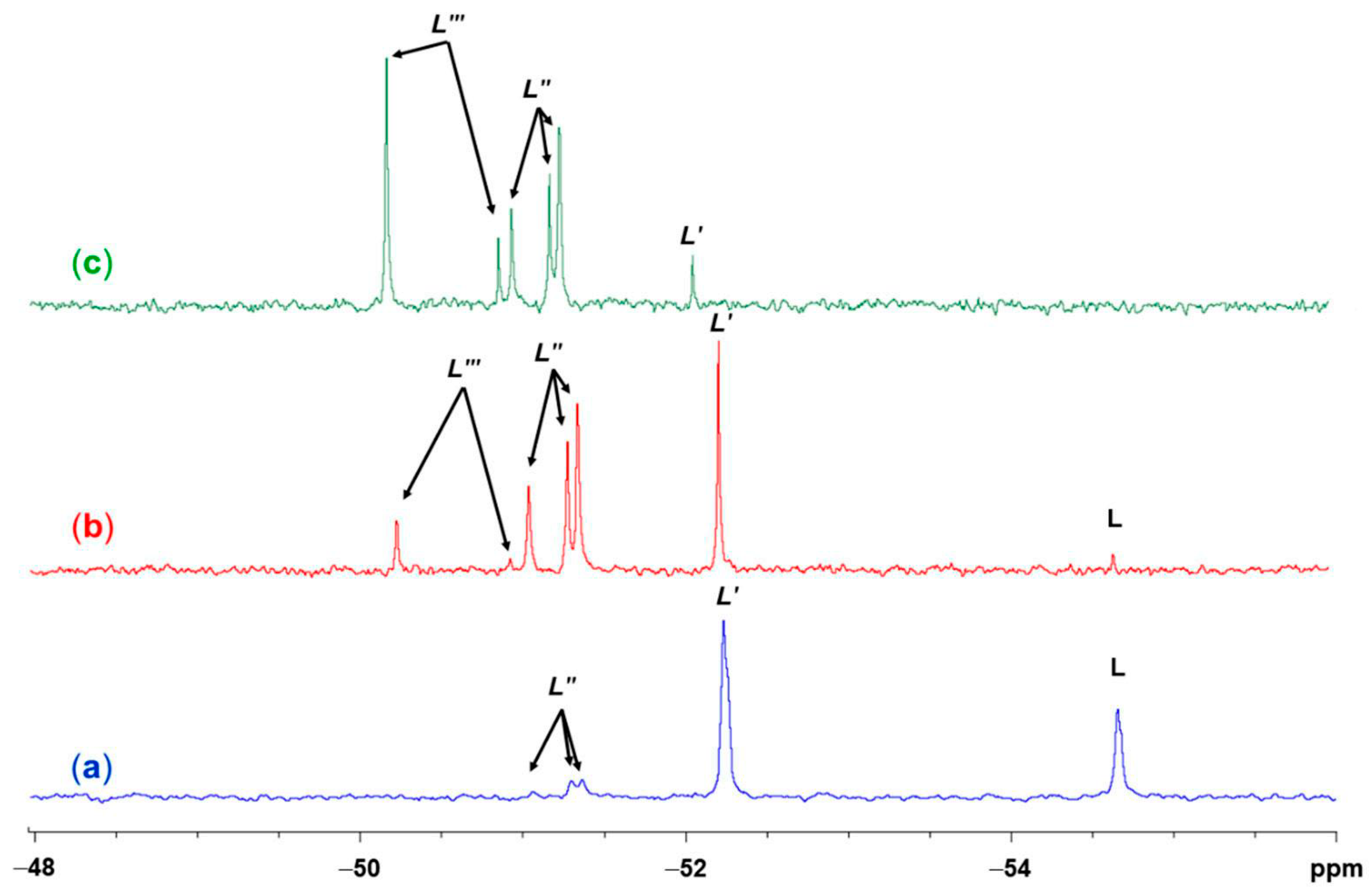

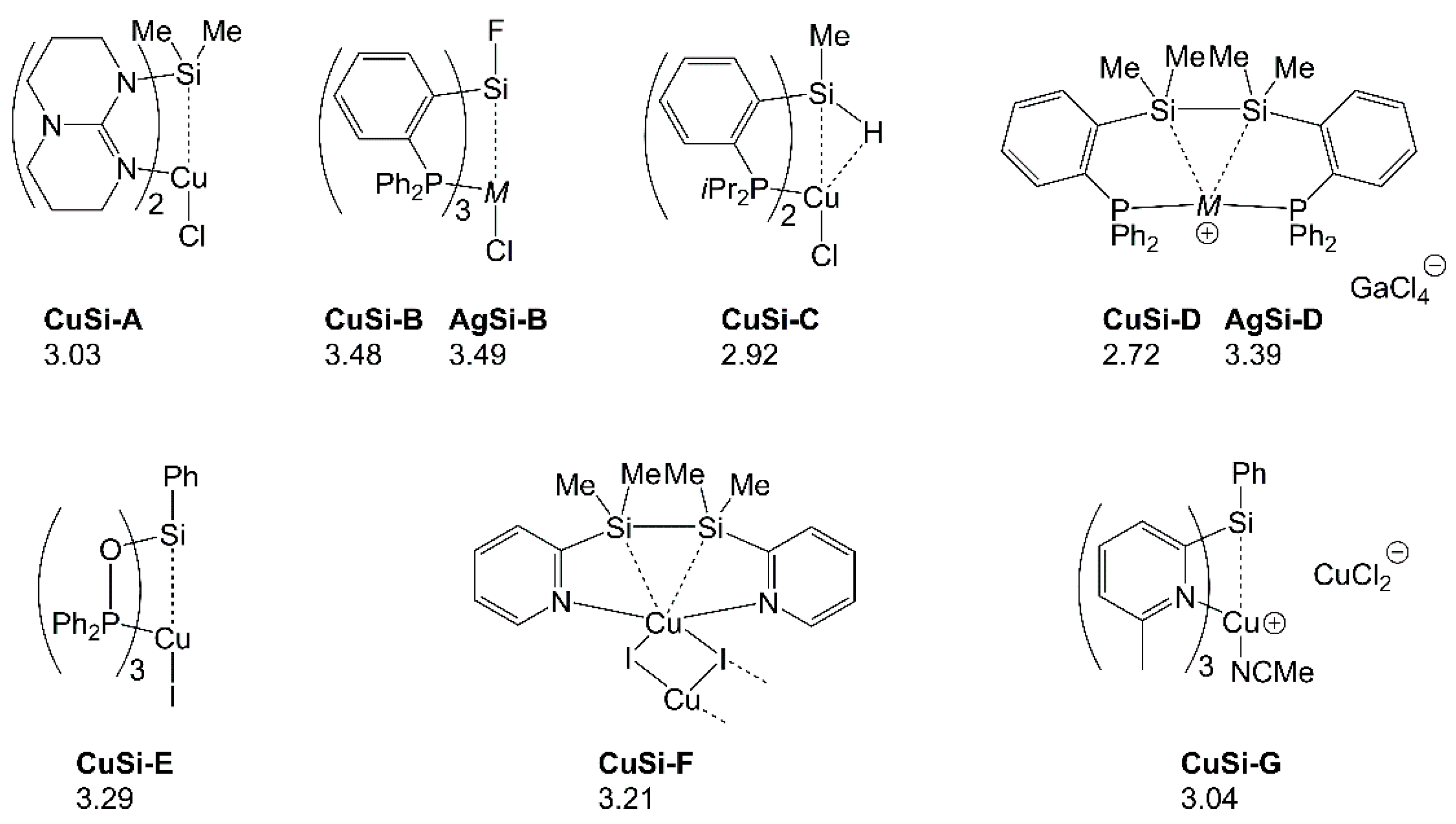

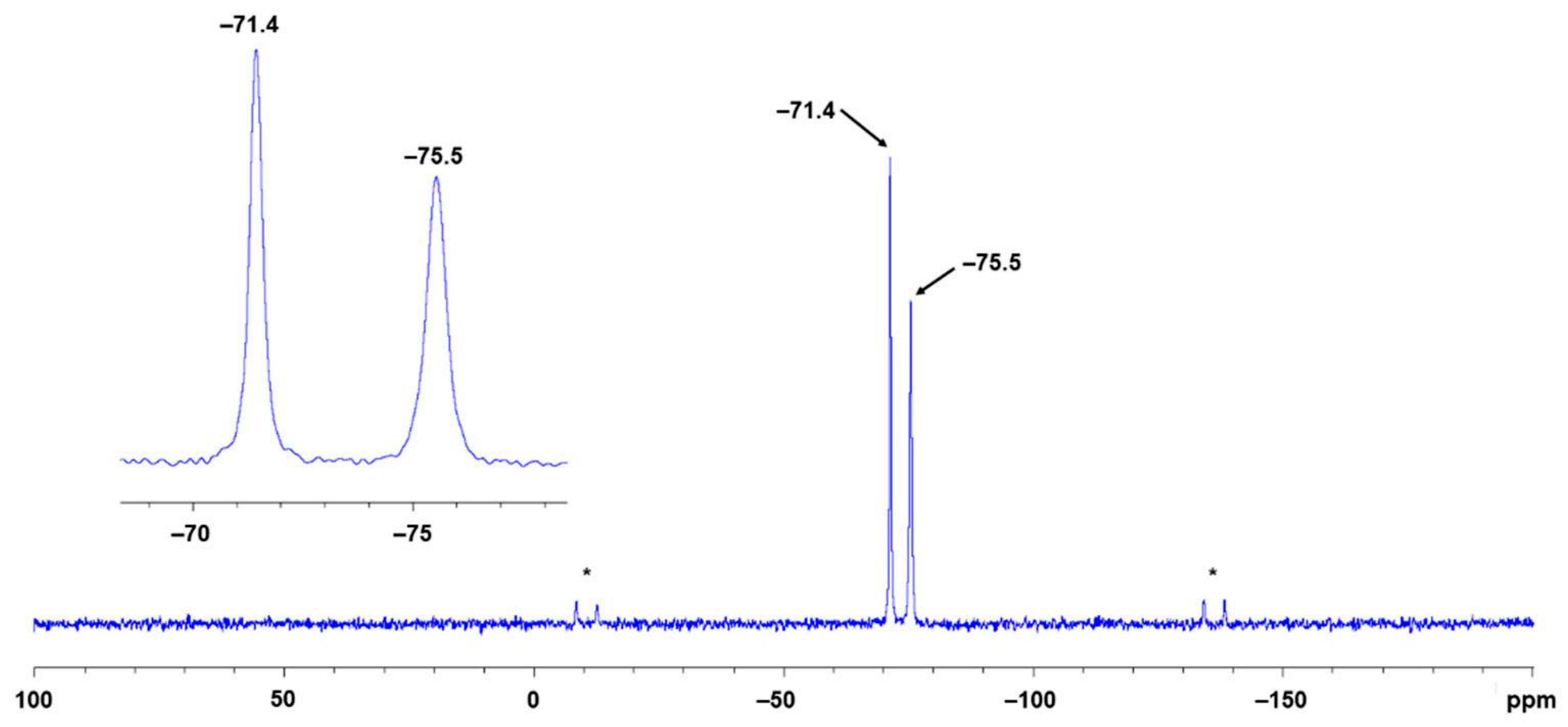

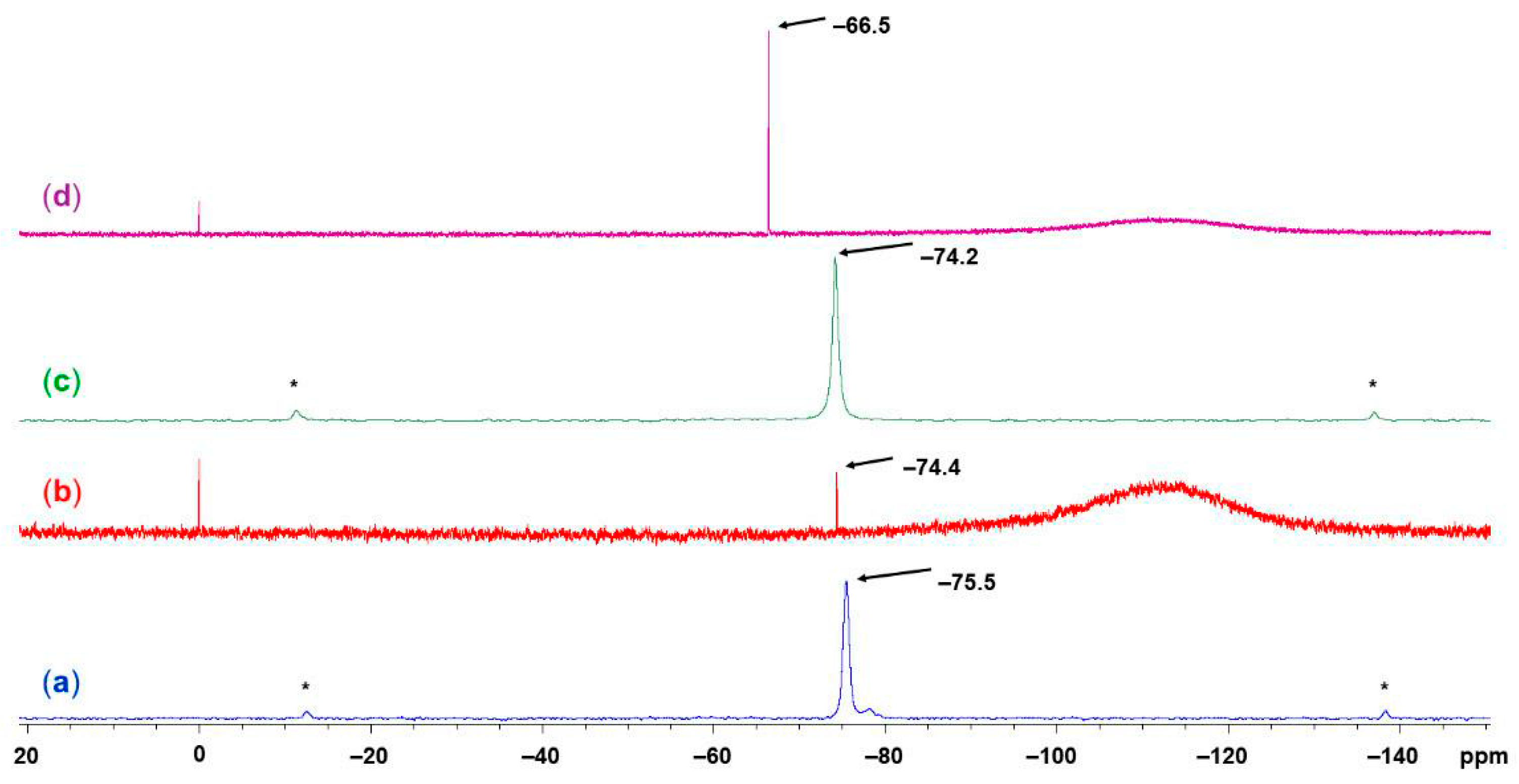

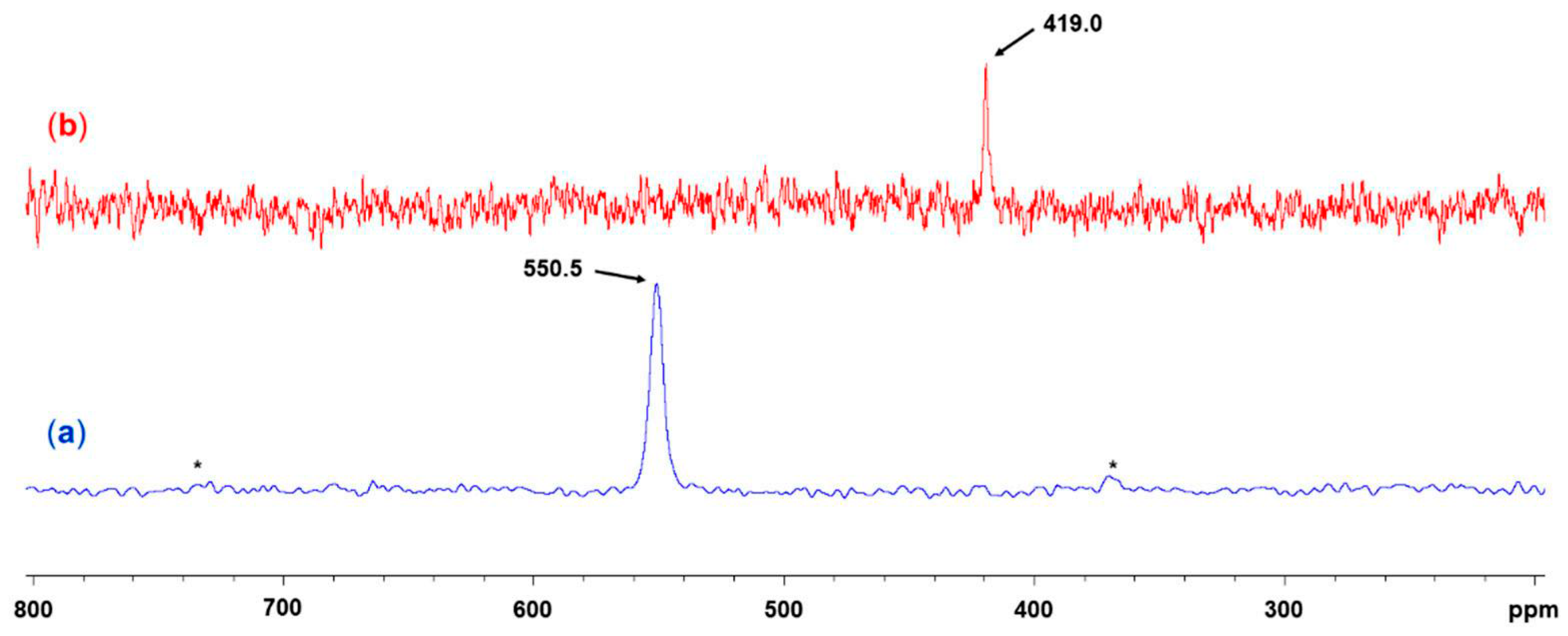

2.4. NMR Spectroscopic Characterization of LCuClCuCl, LCuOTos, and LAgOTos

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Considerations

3.2. Syntheses and Characterization

- Compound LCuClCuCl

- Compound LCuOTos

- Compound LAgOTos

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Parameter | LCuClCuCl | [Cu(HpyO)6](OTos)2 |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | C22H19Cl2Cu2N3O3Si | C44H44CuN6O12S2 |

| Mr | 599.47 | 976.51 |

| T(K) | 180(2) | 180(2) |

| λ(Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c | |

| a(Å) | 9.8896(3) | 9.5568(4) |

| b(Å) | 14.2302(4) | 23.8922(13) |

| c(Å) | 17.4646(4) | 9.8426(4) |

| α(°) | 89.113(2) | 90 |

| β(°) | 88.283(2) | 93.669(3) |

| γ(°) | 76.202(2) | 90 |

| V(Å3) | 2385.72(11) | 2242.78(18) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| ρcalc(g·cm−1) | 1.67 | 1.45 |

| μMoKα (mm−1) | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| F(000) | 1208 | 1014 |

| θmax(°), Rint | 26.0, 0.0348 | 25.0, 0.0922 |

| Completeness | 99.9% | 99.9% |

| Reflns collected | 35,772 | 27,835 |

| Reflns unique | 9385 | 3951 |

| Restraints | 12 | 10 |

| Parameters | 605 | 332 |

| GoF | 1.027 | 1.028 |

| R1, wR2 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0277, 0.0657 | 0.0493, 0.1209 |

| R1, wR2 (all data) | 0.0367, 0.0689 | 0.0777, 0.1321 |

| Largest peak/hole (e·Å−3) | 0.37, −0.35 | 0.34, −0.32 |

| Parameter | LCuOTos Mod1 1 | LCuOTos Mod2 1 | LAgOTos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C29H26CuN3O6SSi | C29H26CuN3O6SSi | C29H26AgN3O6SSi |

| Mr | 636.22 | 636.22 | 680.55 |

| T(K) | 180(2) | 180(2) | 180(2) |

| λ(Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n | P21/n | P21/n |

| a(Å) | 10.6762(5) | 10.4695(6) | 10.6128(2) |

| b(Å) | 9.1920(5) | 28.7746(14) | 28.4084(4) |

| c(Å) | 28.9364(18) | 10.5738(7) | 10.6043(2) |

| β(°) | 91.449(5) | 117.852(4) | 116.952(2) |

| V(Å3) | 2838.8(3) | 2816.4(3) | 2849.87(10) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ρcalc(g·cm−1) | 1.49 | 1.50 | 1.59 |

| μMoKα (mm−1) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| F(000) | 1312 | 1312 | 1384 |

| θmax(°), Rint | 26.0, 0.0907 | 25.0, 0.0793 | 28.0, 0.0354 |

| Completeness | 99.9% | 99.8% | 100% |

| Reflns collected | 25,592 | 19,178 | 68,380 |

| Reflns unique | 5585 | 4958 | 6858 |

| Restraints | 45 | 0 | 13 |

| Parameters | 400 | 371 | 394 |

| GoF | 0.995 | 1.027 | 1.064 |

| R1, wR2 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0410, 0.0980 | 0.0615, 0.1577 | 0.0225, 0.0579 |

| R1, wR2 (all data) | 0.0813, 0.1083 | 0.1004, 0.1777 | 0.0263, 0.0594 |

| Largest peak/hole (e·Å−3) | 0.46, −0.44 | 1.80, −0.41 2 | 0.42, −0.36 |

References

- Singh, G.; Kaur, G.; Singh, J. Progressions in hyper–coordinate silicon complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 88, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemière, G.; Millanvois, A.; Ollivier, C.; Fensterbank, L. A Parisian Vision of the Chemistry of Hypercoordinated Silicon Derivatives. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, J.; Böhme, U.; Kroke, E. Higher-Coordinated Molecular Silicon Compounds. In Functional Molecular Silicon Compounds I-Regular Oxidation States; Scheschkewitz, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 115, pp. 29–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuit, C.; Corriu, R.J.P.; Reye, C.; Young, J.C. Reactivity of Penta- and Hexacoordinate Silicon Compounds and Their Role as Reaction Intermediates. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1371–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloquin, D.M.; Schmedake, T.A. Recent advances in hexacoordinate silicon with pyridine-containing ligands: Chemistry and emerging applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 323, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassindale, A.R.; Glynn, S.J.; Taylor, P.G. Chapter 9: Reaction Mechanisms of Nucleophilic Attack at Silicon. In The Chemistry of Organic Silicon Compounds; Rappoport, Z., Apeloig, Y., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.S. Correlation of Rates of Intramolecular Tunneling Processes, with Application to Some Group V Compounds. J. Chem. Phys. 1960, 32, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishna, A.; Pete, S.; Mhaskar, C.M.; Ramann, H.; Ramanaiah, D.V.; Arbaaz, M.; Niyaz, M.; Janardan, S.; Suman, P. Role of hypercoordinated silicon(IV) complexes in activation of carbon–silicon bonds: An overview on utility in synthetic chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 485, 215140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, N.; Henn, J.; Gostevskii, B.; Kost, D.; Kalikhman, I.; Engels, B.; Stalke, D. Si–E (E = N, O, F) Bonding in a Hexacoordinated Silicon Complex: New Facts from Experimental and Theoretical Charge Density Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5563–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korlyukov, A.A.; Lyssenko, K.A.; Antipin, M.Y.; Kirin, V.N.; Chernyshev, E.A.; Knyazev, S.P. Experimental and Theoretical Study of the Transannular Intramolecular Interaction and Cage Effect in the Atrane Framework of Boratrane and 1-Methylsilatrane. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 5043–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fester, G.W.; Wagler, J.; Brendler, E.; Böhme, U.; Roewer, G.; Kroke, E. Octahedral Adducts of Dichlorosilane with Substituted Pyridines: Synthesis, Reactivity and a Comparison of Their Structures and 29Si NMR Chemical Shifts. Chem.-Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3164–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobe, J.; Wehmschulte, R.; Krebs, B.; Läge, M. Alternativ-Liganden. XXXII Neue Tetraphosphan-Nickelkomplexe mit Tripod-Liganden des Typs XM’(OCH2PMe2)n(CH2CH2PR2)3-n (M’ = Si, Ge; n = 0–3). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1995, 621, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobe, J.; Lütke-Brochtrup, K.; Krebs, B.; Läge, M.; Niemeyer, H.-H.; Würthwein, E.-U. Alternativ-Liganden XXXVIII. Neue Versuche zur Synthese von Pd(0)- und Pt(0)-Komplexen des Tripod-Phosphanliganden FSi(CH2CH2PMe2)3. Z. Naturforschung 2007, 62, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualco, P.; Lin, T.-P.; Sircoglou, M.; Mercy, M.; Ladeira, S.; Bouhadir, G.; Pérez, L.M.; Amgoune, A.; Maron, L.; Gabbaï, F.P.; et al. Gold–Silane and Gold–Stannane Complexes: Saturated Molecules as σ-Acceptor Ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9892–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, J.; Brendler, E. Metallasilatranes: Palladium(II) and Platinum(II) as Lone-Pair Donors to Silicon(IV). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truflandier, L.A.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J.; Autschbach, J. 29Si DFT/NMR Observation of Spin–Orbit Effect in Metallasilatrane Sheds Some Light on the Strength of the Metal→Silicon Interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlicht, S.; Brendler, E.; Heine, T.; Zhechkov, L.; Wagler, J. 7-Azaindol-1-yl(organo)silanes and Their PdCl2 Complexes: Pd-Capped Tetrahedral Silicon Coordination Spheres and Paddlewheels with a Pd-Si Axis. Organometallics 2014, 33, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipke, M.C.; Liberman-Martin, A.L.; Tilley, T.D. Electrophilic Activation of Silicon–Hydrogen Bonds in Catalytic Hydrosilations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2260–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonov, G.I. Recent Advances in Nonclassical Interligand Si…H Interactions. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 53, 217–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kira, M.; Sakurai, H. Allylation of α-Hydroxy Ketones with Allyltrifluorosilanes and Allyltrialkoxysilanes in the Presence of Triethylamine. Stereochemical Regulation Involving Chelated Bicyclic Transition States. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6429–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, M.; Zhang, L.C.; Kabuto, C.; Sakurai, H. Synthesis and Reactions of Neutral Hypercoordinate Allylsilicon Compounds Having a Tropolonato Ligand. Organometallics 1996, 15, 5335–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, J.; Roewer, G. Syntheses of Allyl- and 3-Silylpropyl-substituted Salen-like Tetradentate Ligands via Hypercoordinate Silicon Complexes. Z. Naturforschung B 2006, 61, 1406–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächtler, E.; Kämpfe, A.; Krupinski, K.; Gerlach, D.; Kroke, E.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. New Insights into Hexacoordinated Silicon Complexes with 8-Oxyquinolinato Ligands: 1,3-Shift of Si-Bound Hydrocarbyl Substituents and the Influence of Si-Bound Halides on the 8-Oxyquinolinate Coordination Features. Z. Naturforschung B 2014, 69, 1402–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Yamamura, M.; Kawashima, T. Reactivity Control of an Allylsilane Bearing a 2-(Phenylazo)phenyl Group by Photoswitching of the Coordination Number of Silicon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6250–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostevskii, B.; Kalikhman, I.; Tessier, C.A.; Panzner, M.J.; Youngs, W.J.; Kost, D. Hexacoordinate Complexes of Silacyclobutane: Spontaneous Ring Opening and Rearrangement. Organometallics 2005, 24, 5786–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fester, G.W.; Eckstein, J.; Gerlach, D.; Wagler, J.; Brendler, E.; Kroke, E. Reactions of Hydridochlorosilanes with 2,2′-Bipyridine and 1,10-Phenanthroline: Complexation versus Dismutation and Metal-Catalyst-Free 1,4-Hydrosilylation. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 2667–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippe, K.; Gerlach, D.; Kroke, E.; Wagler, J. Hypercoordinate Organosilicon Complexes of an ONN′O′ Chelating Ligand: Regio- and Diastereoselectivity of Rearrangement Reactions in Si-Salphen Systems. Organometallics 2009, 28, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalikhman, I.; Gostevskii, B.; Kertsnus, E.; Botoshansky, M.; Tessier, C.A.; Youngs, W.J.; Deuerlein, S.; Stalke, D.; Kost, D. Competitive Molecular Rearrangements in Hexacoordinate Cyano-Silicon Dichelates. Organometallics 2007, 26, 2652–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzawa, K.; Ueno, M.; Wheatley, A.E.H.; Kondo, Y. Phosphazene Base Promoted Functionalization of Aryltrimethylsilanes. Chem. Commun. 2006, 42, 4850–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, J.; Roewer, G.; Gerlach, D. Photo Driven Si C Bond Cleavage in Hexacoordinate Silicon Complexes. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendler, E.; Wächtler, E.; Wagler, J. Hypercoordinate Silacycloalkanes: Step-by-Step Tuning of N→Si Interactions. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5459–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, Y.; Hiyama, T. Designing Cross-Coupling Reactions using Aryl(trialkyl)silanes. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, C.; Zhang, B.-B.; Zhang, G.; Peng, A.; Wang, Z.-X.; Shi, Q.; Huang, H. An Efficient C−Si/C−H Cross-Coupling Reaction Enabled by a Radical Pathway. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202303857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, Y.; Hiyama, T. Cross-Coupling of Organosilanes with Organic Halides Mediated by Palladium Catalyst and Tris(diethylamino)sulfonium Difluorotrimethylsilicate. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Fujita, K.; Itami, K.; Yoshida, J. Copper-Catalyzed Allylation of Carbonyl Derivatives Using Allyl(2-pyridyl)silanes. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4725–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsubouchi, A.; Muramatsu, D.; Takeda, T. Copper(I)-Catalyzed Alkylation of Aryl- and Alkenylsilanes Activated by Intramolecular Coordination of an Alkoxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 125, 12719–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, T.; Matsumura, R.; Wasa, H.; Tsubouchi, A. Copper(I)-Promoted Alkylation of Alkenylbenzyldimethylsilanes. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3, 838–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, L.; Gericke, R.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. (2-Pyridyloxy)silanes as Ligands in Transition Metal Coordination Chemistry. Inorganics 2018, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A.; Gericke, R.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. Copper Complexes of Silicon Pyridine-2-olates RSi(pyO)3 (R = Me, Ph, Bn, Allyl) and Ph2Si(pyO)2. Inorganics 2023, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lumata, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Kovacs, Z.; Sherry, A.D.; Khemtong, C. Hyperpolarized 15N-pyridine Derivatives as pH-Sensitive MRI Agents. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheenhy, K.J.; Bateman, L.M.; Flosbach, N.T.; Breugst, M.; Byrne, P.A. Identification of N- or O-Alkylation of Aromatic Nitrogen Heterocycles and N-Oxides Using 1H–15N HMBC NMR Spectroscopy. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 22, 3270–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A.; Weigel, M.; Ehrlich, L.; Gericke, R.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. Molecular Structures of the Silicon Pyridine-2-(thi)olates Me3Si(pyX), Me2Si(pyX)2 and Ph2Si(pyX)2 (py = 2-Pyridyl, X = O, S), and Their Intra- and Intermolecular Ligand Exchange in Solution. Crystals 2022, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuß, S.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. Molecular Structures of the Pyridine-2-olates PhE(pyO)3 (E = Si, Ge, Sn) – [4+3]-Coordination at Si, Ge vs. Heptacoordination at Sn. Crystals 2022, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliegel, W.; Motzkus, H.-W.; Nanninga, D.; Rettig, S.J.; Trotter, J. Structural studies of organoboron compounds XXIII: Preparation and crystal and molecular structures of 2,2-diphenyl-l,3-dioxa-4a-azonia-2-borata-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene and 4,4-diphenyl-3-oxa-l-aza-4a-azonia-4-borata-l,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene. Can. J. Chem. 1986, 64, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.-X.; Schwedtmann, K.; Fidelius, J.; Hennersdorf, F.; Dickschat, A.; Bauzá, A.; Weigand, J.J. Bifunctional Fluorophosphonium Triflates as Intramolecular Frustrated Lewis Pairs: Reversible CO2 Sequestration and Binding of Carbonyls, Nitriles and Acetylenes. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 13709–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, E.; Markus, F.; Meske, H.; Tropsch, J.; Maas, G. Anomer kontrollierte Substitutionsreaktionen mit verschiedenen N-Alkylpyridiniumverbindungen. Chem. Ber. 1987, 120, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordiichuk, O.R.; Kinzhybalo, V.V.; Goreshnik, E.A.; Slyvka, Y.I.; Krawczyk, M.S.; Mys’kiv, M.G. Influence of apical ligands on Cu–(C=C) interaction in Copper(I) halides (Cl−, Br−, I−) π-complexes with an 1,2,4-triazole allyl-derivative: Syntheses, crystal structures and NMR spectroscopy. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 838, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyvka, Y.; Fed’ko, A.; Goreshnik, E.; Kordan, V.; Mys’kiv, M. A new hybrid inorganic-organic coordination copper(I) chloride π,σ-compound [Cu4(C18H17N5OS)2Cl4]·2H2O·2C3H7OH based on N-phenyl-N’-{3-allylsulfanyl-4-amino-5-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl}urea: Synthesis and structure characterization. Chem. Met. Alloys 2021, 14, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddel’sky, A.I.; Smolyaninov, I.V.; Druzhkov, N.O.; Fukin, G.K. Heterometallic antimony(V)-zinc and antimony(V)-copper complexes comprising catecholate and diazadiene as redox active centers. J. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 952, 121994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, E.; Yang, C.; Li, L.; Golen, J.A.; Rheingold, A.L. Copper(II) Complexes of 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine Derivatives for Catalytic Aerobic Alcohol Oxidations–Observation of Mixed-Valence CuICuII Assembles. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-H.; Chang, F.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Rachlewicz, K.; Stȩpień, M.; Latos-Grażyński, L.; Lee, G.-H.; Peng, S.-M. Iron and Copper Complexes of Tetraphenyl-m-benziporphyrin: Reactivity of the Internal C-H Bond. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 4118–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, S.S.; Thompson, L.K.; Bridson, J.N.; McKee, V.; Downard, A.J. Dinuclear copper(II) and polymeric tetranuclear copper(II) and copper(II)-copper(I) complexes of macrocyclic ligands capable of forming endogenous alkoxide and phenoxide bridges. Structural, magnetic, and electrochemical studies. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 4635–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak-Akimova, E.; Busch, D.H.; Kahol, P.K.; Pinto, N.; Alcock, N.W.; Clase, H.J. Dicopper Complexes with a Dissymmetric Dicompartmental Schiff Base−Oxime Ligand: Synthesis, Structure, and Magnetic Interactions. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, A. van der Waals Volumes and Radii. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, S.H.; Coles, M.P.; Hitchcock, P.B. Poly(guanidyl)silanes as a new class of chelating, N-based ligand. Dalton Trans. 2004, 33, 1113–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameo, H.; Kawamoto, T.; Bourissou, D.; Sakaki, S.; Nakazawa, H. Evaluation of the σ-Donation from Group 11 Metals (Cu, Ag, Au) to Silane, Germane, and Stannane Based on the Experimental/Theoretical Systematic Approach. Organometallics 2015, 34, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-E.; Kim, J.; Park, J.W.; Park, K.; Lee, Y. σ-Complexation as a strategy for designing copper-based light emitters. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2858–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualco, P.; Amgoune, A.; Miqueu, K.; Ladeira, S.; Bourissou, D. A Crystalline σ Complex of Copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4257–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloisi, A.; Berthet, J.-C.; Genre, C.; Thuéry, P.; Cantat, T. Complexes of the tripodal phosphine ligands PhSi(XPPh2)3 (X = CH2, O): Synthesis, structure and catalytic activity in the hydroboration of CO2. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 14774–14788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Nakae, T.; Takea, S.; Hattori, M.; Saito, D.; Kato, M.; Ohmasa, Y.; Sato, S.; Yamamuro, O.; Galica, T.; et al. Reversible Transition between Discrete and 1D Infinite Architectures: A Temperature-Responsive Cu(I) Complex with a Flexible Disilane-Bridged Bis(pyridine) Ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202204022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plajer, A.J.; Colebatch, A.L.; Enders, M.; García-Romero, Á.; Bond, A.D.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Wright, D.S. The coordination chemistry of the neutral tris-2-pyridyl silicon ligand [PhSi(6-Me-2-py)3]. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7036–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.D.; von Goldammer, E. NMR Chemical Shifts in the Silver Halides. Chem. Phys. 1980, 48, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.; Docherty, S.R.; Cao, W.; Yakimov, A.V.; Copéret, C. 109Ag NMR chemical shift as a descriptor for Brønsted acidity from molecules to materials. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3028–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, G.H.; Li, W. Silver-109 NMR Spectroscopy of Inorganic Solids. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 5588–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Tang, G.-M.; Wang, Y.-T. A set of Ag-based metal coordination polymers with sulfonate group: Syntheses, crystal structures and luminescent behaviors. Polyhedron 2018, 148, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.K.; Becker, E.D.; Cabral de Menezes, S.M.; Goodfellow, R.; Granger, P. NMR nomenclature. Nuclear spin properties and conventions for chemical shifts (IUPAC Recommendations 2001). Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1795–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merwin, L.H.; Sebald, A. The first examples of 109Ag CP MAS spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 1992, 97, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebald, A. MAS and CP/MAS of Less Common Spin-1/2 Nuclei. In Solid State NMR II: Inorganic Matter; Diehl, P., Fluck, E., Günther, H., Kosfeld, R., Seelig, J., Eds.; book series: NMR Basic Principles and Progress; Blümich, B., Ed. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; Volume 31, pp. 91–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Program for the Refinement of Crystal Structures; SHELXL-2019/3; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2007, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. ORTEP-3 for windows—A version of ORTEP-III with a graphical user interface (GUI). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POV-RAY (Version 3.7), Trademark of Persistence of Vision Raytracer Pty. Ltd., Williamstown, Victoria (Australia). Copyright Hallam Oaks Pty. Ltd., 1994–2004. Available online: http://www.povray.org/download/ (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Cryst. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagler, J.; Gericke, R. Ge–Cu-Complexes Ph(pyO)Ge(μ2-pyO)2CuCl and PhGe(μ2-pyO)4CuCl—Representatives of Cu(I)→Ge(IV) and Cu(II)→Ge(IV) Dative Bond Systems. Molecules 2023, 28, 5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. The crystal structure of Hexakis(2-pyridone)copper(II) perchlorate. Aust. J. Chem. 1975, 28, 2615–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, S.R.; Wang, S. Hydrogen-bond-directed assembly of one-dimensional and two-dimensional polymeric copper(II) complexes with trifluoroacetate and hydroxypyridine as ligands: Syntheses and structural investigations. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 5981–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

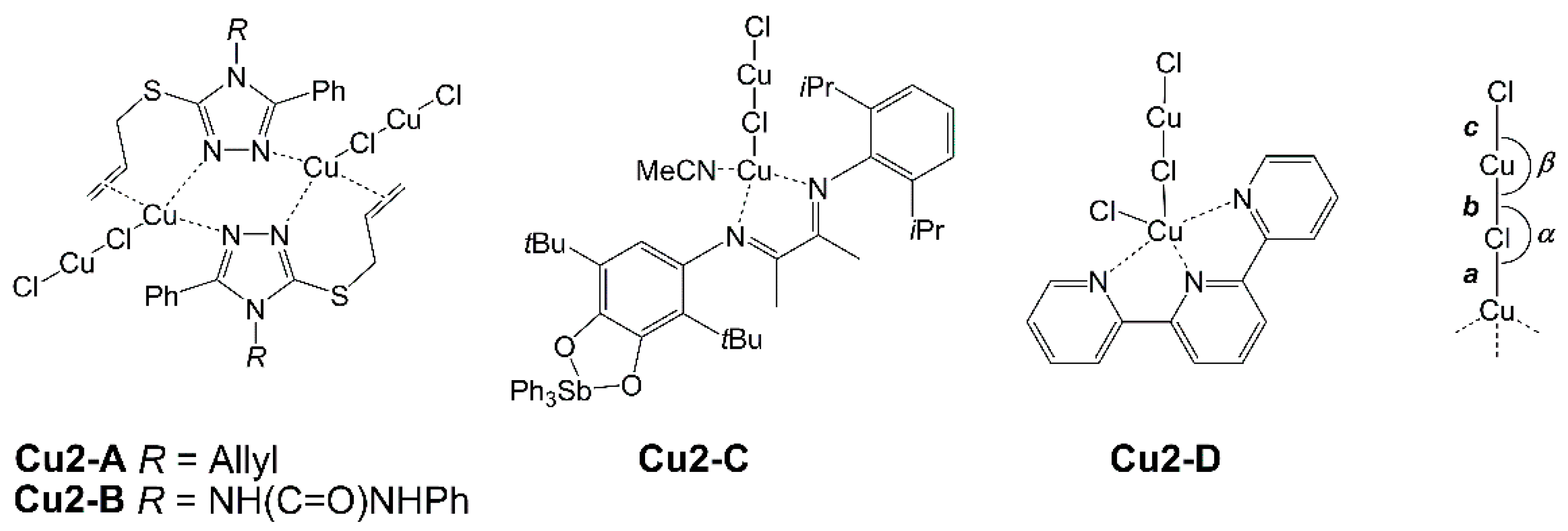

| LCuClCuCl | Cu2-A | Cu2-B | Cu2-C | Cu2-D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 2.4366(6) | 2.63 | 2.54 | 2.43 | 2.81 |

| b | 2.1115(7) | 2.10 | 2.13 | 2.11 | 2.13 |

| c | 2.0786(8) | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.10 | 2.11 |

| α | 109.00(3) | 101.6 | 105.8 | 118.4 | 92.5 |

| β | 177.35(3) | 175.7 | 160.5 | 177.7 | 176.8 |

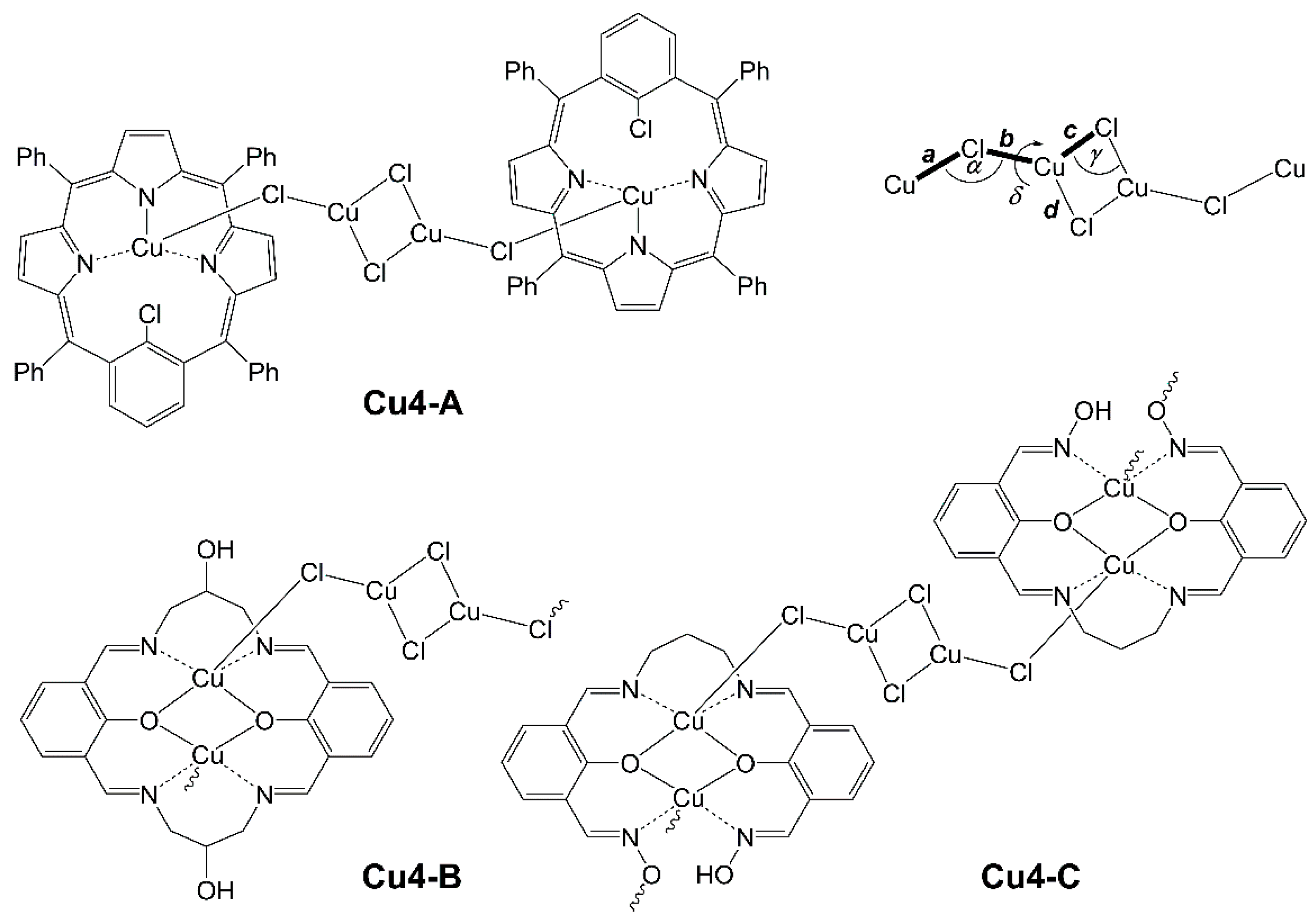

| LCuClCuCl | Cu2-B | Cu4-A | Cu4-B | Cu4-C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 2.4545(6) | 2.54 | 2.49 | 2.65 | 2.65 |

| b | 2.2080(8) | 2.22 | 2.19 | 2.14 | 2.15 |

| c | 2.2739(10) | 2.71 | 2.30 | 2.38 | 2.47 |

| d | 2.3691(16) | 2.14 | 2.31 | 2.24 | 2.21 |

| α | 131.88(4) | 98.7 | 110.2 | 111.8 | 108.5 |

| γ | 77.85(3) | 77.8 | 75.1 | 79.0 | 79.4 |

| δ | 148.30(7) | 111.7 | 137.9 | 164.9 | 164.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Münzner, S.; Brendler, E.; Wagler, J. Reactions of Benzylsilicon Pyridine-2-olate BnSi(pyO)3 and Selected Electrophiles—PhCHO, CuCl, and AgOTos. Inorganics 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010020

Münzner S, Brendler E, Wagler J. Reactions of Benzylsilicon Pyridine-2-olate BnSi(pyO)3 and Selected Electrophiles—PhCHO, CuCl, and AgOTos. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMünzner, Saskia, Erica Brendler, and Jörg Wagler. 2026. "Reactions of Benzylsilicon Pyridine-2-olate BnSi(pyO)3 and Selected Electrophiles—PhCHO, CuCl, and AgOTos" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010020

APA StyleMünzner, S., Brendler, E., & Wagler, J. (2026). Reactions of Benzylsilicon Pyridine-2-olate BnSi(pyO)3 and Selected Electrophiles—PhCHO, CuCl, and AgOTos. Inorganics, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010020