1. Introduction

Alkali–tantalum(V) oxyfluorides KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F were first reported by Magneli and Nord in 1965 and Babel et al. in 1967, respectively [

1,

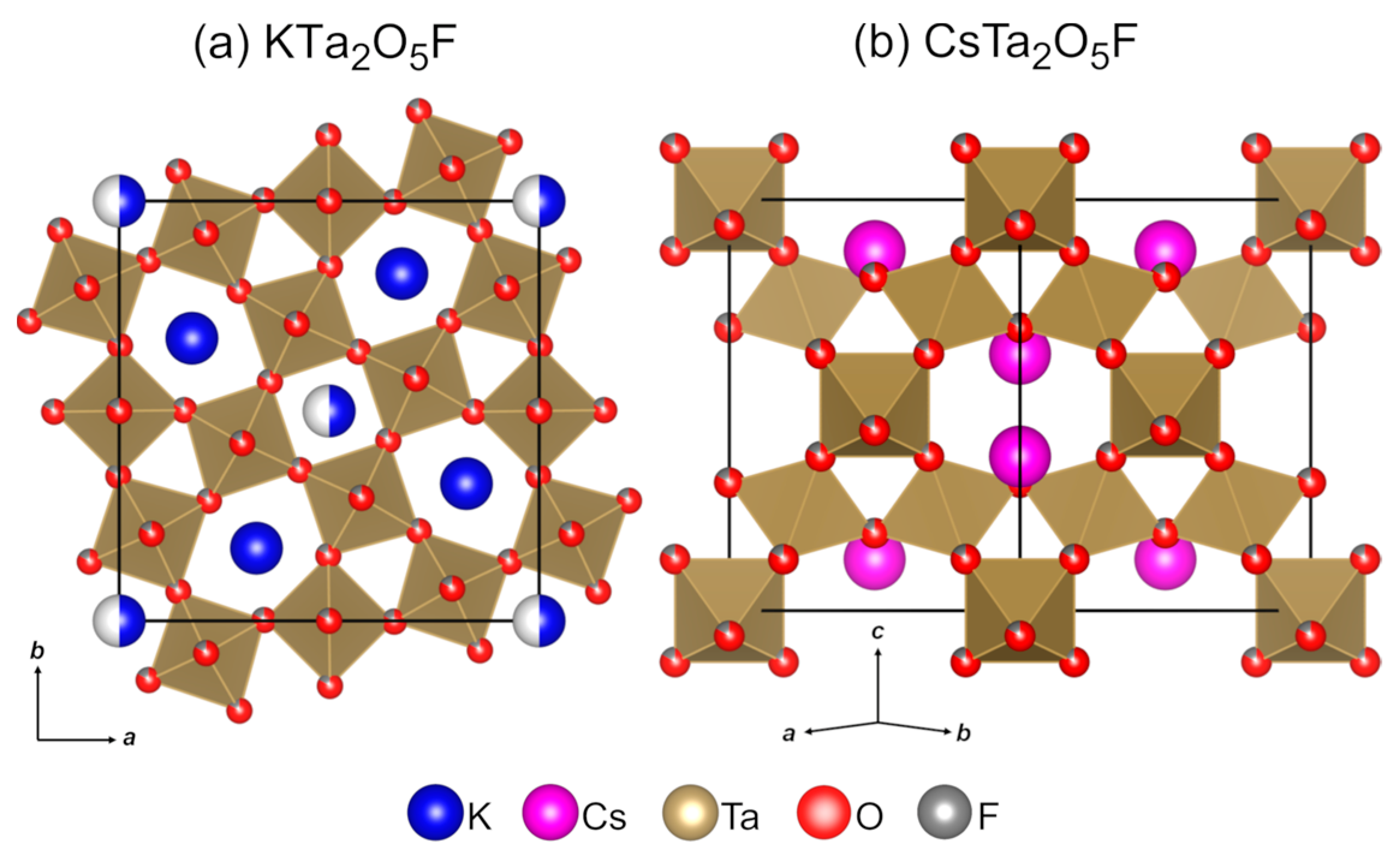

2]. Their crystal structures are shown in

Figure 1. KTa

2O

5F exhibits a tetragonal tungsten bronze structure (space group

P4/

mbm, see

Figure 1a). It consists of a framework of corner-sharing Ta(O/F)

6 octahedra and potassium ions located in channels that extend along the

c axis. The crystal structure of CsTa

2O

5F is a cubic pyrochlore that features a compact arrangement of corner-sharing Ta(O/F)

6 octahedra (space group

Fdm, see

Figure 1b). The anionic substructures of KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F exhibit occupational disorder of oxygen and fluorine. Both oxyfluorides were reported several decades ago and have been explored as ionic conductors along with their alkali–niobium(V) counterparts [

3,

4]. Despite these facts, two fundamental gaps persist when it comes to their synthesis and structural depiction. With regard to their preparation, a comprehensive review of the literature presented in

Table 1 demonstrates the absence of straightforward solid-state routes to KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F. Synthetic strategies utilized so far involve solid-state reactions requiring specialized reaction containers, molten salts, and inert atmosphere [

1,

2,

3,

5]. A combination of these experimental configurations and conditions was employed for the preparation of KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F as byproducts from the electrolysis of K

3TaOF

6 and Cs

3TaOF

6, respectively [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Unlike KTa

2O

5F, CsTa

2O

5F has also been prepared using solution-based approaches involving hydrothermal reactions. However, these required the use of corrosive solvents (HF

(aq)) [

9] or extreme hydrothermal conditions (575 °C, 20,000 psi) [

10]. To the best of our knowledge, a straightforward solid-state route to KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F is yet to be reported; that is, one in which phase-pure oxyfluorides are obtained upon heating a reaction mixture in a regular alumina crucible under ambient atmosphere. Additionally, a gap exists in the structural characterization of the tetragonal tungsten bronze KTa

2O

5F. As shown in

Table 1, previous investigations that reported the preparation of this oxyfluoride did not conduct quantitative analysis of X-ray diffraction data. As a result, there are no entries for KTa

2O

5F in either the International Center for Diffraction Data

Powder Diffraction File (ICDD–PDF) or in the

Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). For completeness, we note that crystal structures displayed in

Figure 1 were built by replacing Ta

5+ for Nb

5+ (

rTa5+ =

rNb5+ = 0.64 Å) [

11] in tetragonal KNb

2O

5F (isomorphous to KTa

2O

5F) and cubic CsNb

2O

5F (isomorphous to CsTa

2O

5F) [

12,

13,

14]. The corresponding structural parameters are given in the

Supporting Information (Table S1).

The primary aim of this study was to streamline the solid-state synthesis of alkali–tantalum(V) oxyfluorides KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F. Alkali fluorides and trifluoroacetates and tantalum(V) oxide were used as metal precursors. Thermal analysis and Rietveld analysis of powder diffraction data were employed to identify reaction conditions that yielded single-phase oxyfluorides under ambient atmosphere. Additionally, the crystal structure of KTa

2O

5F was quantitatively probed using neutron powder diffraction. Results presented herein complement those recently reported by our group on the solid-state preparation of alkali–niobium(V) oxyfluorides KNb

2O

5F and CsNb

2O

5F [

15].

2. Results and Discussion

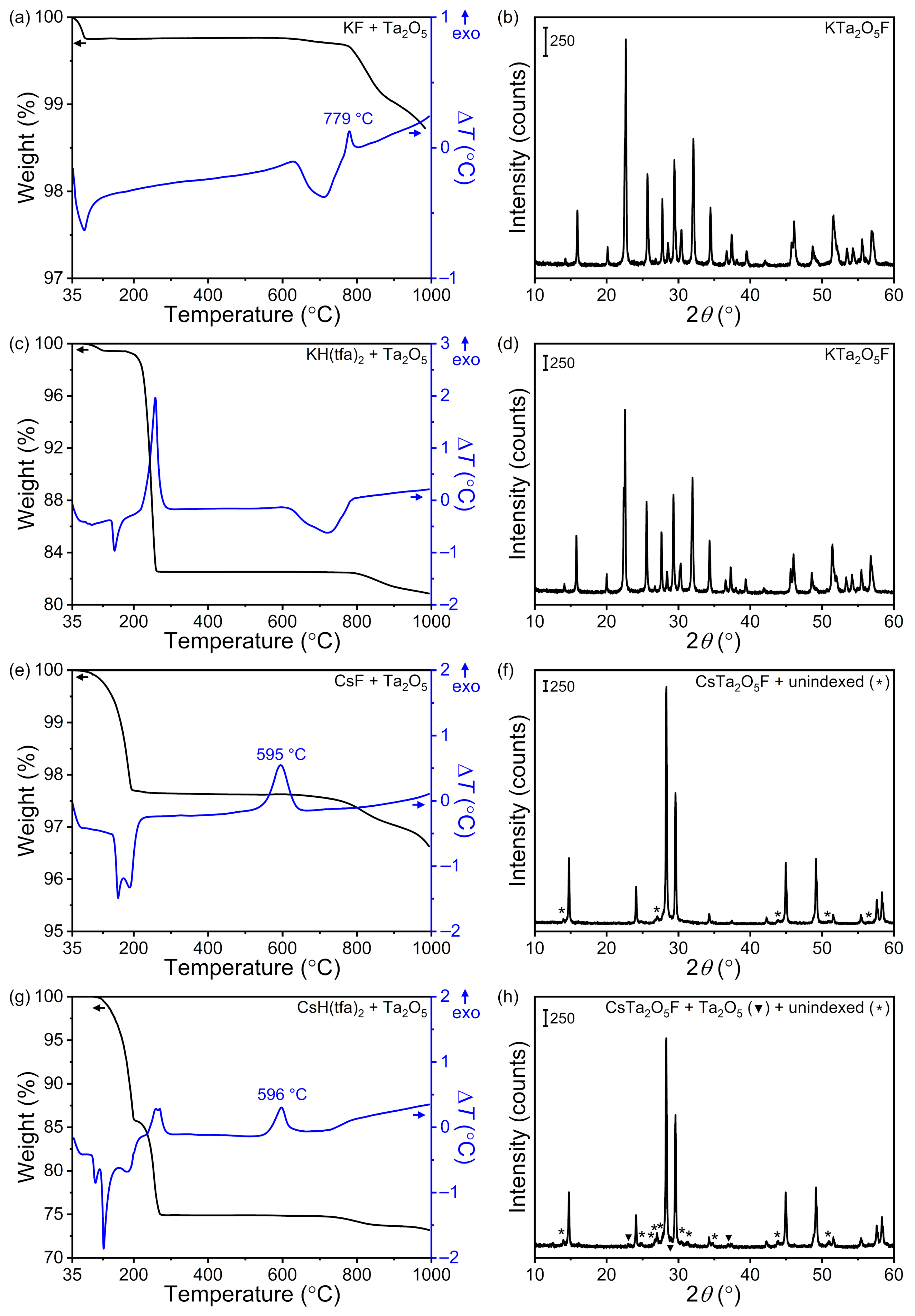

Reactions between alkali fluorides and trifluoroacetates and Ta

2O

5 were first carried out in a TGA–DTA analyzer under flowing synthetic air with the goal of determining reaction temperatures for ambient synthesis. Besides providing us an accurate thermal profile of each reaction, this experimental configuration enabled precise control over reaction atmosphere. Such control was important because of the hygroscopic nature of both the reactants and the target products, which could impact reaction outcomes. Results from reactivity studies conducted in the TGA–DTA analyzer are summarized in

Figure 2, where reaction thermal profiles and PXRD patterns of the corresponding products are shown. Reaction between KF and Ta

2O

5 resulted in the crystallization of KTa

2O

5F at 779 °C, as indicated by an exothermic peak in the DTA trace (

Figure 2a). All diffraction maxima in the PXRD pattern were indexed to that oxyfluoride phase; no secondary crystalline phases were observed (

Figure 2b). Similar results were obtained upon reacting KH(tfa)

2 and Ta

2O

5. The only difference was that no exothermic peak indicating crystallization of KTa

2O

5F was clearly observable in the DTA trace (

Figure 2c), despite the fact that the oxyfluoride was the only crystalline phase obtained according to PXRD (

Figure 2d). In the case of CsTa

2O

5F, crystallization from a CsF + Ta

2O

5 mixture occurred at 595 °C (

Figure 2e). The resulting solid consisted of the targeted oxyfluoride phase as well as a secondary crystalline phase whose diffraction maxima could not be indexed (

Figure 2f). The same crystallization temperature was extracted from the thermal profile of the CsH(tfa)

2 + Ta

2O

5 mixture (

Figure 2g). However, in such a case, the resulting solid comprised CsTa

2O

5F, Ta

2O

5 (PDF No. 01–079–1375), and an unindexed phase (

Figure 2h). With these results in hand, we chose 800 and 600 °C as the starting reaction temperatures for the synthesis of KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F, respectively.

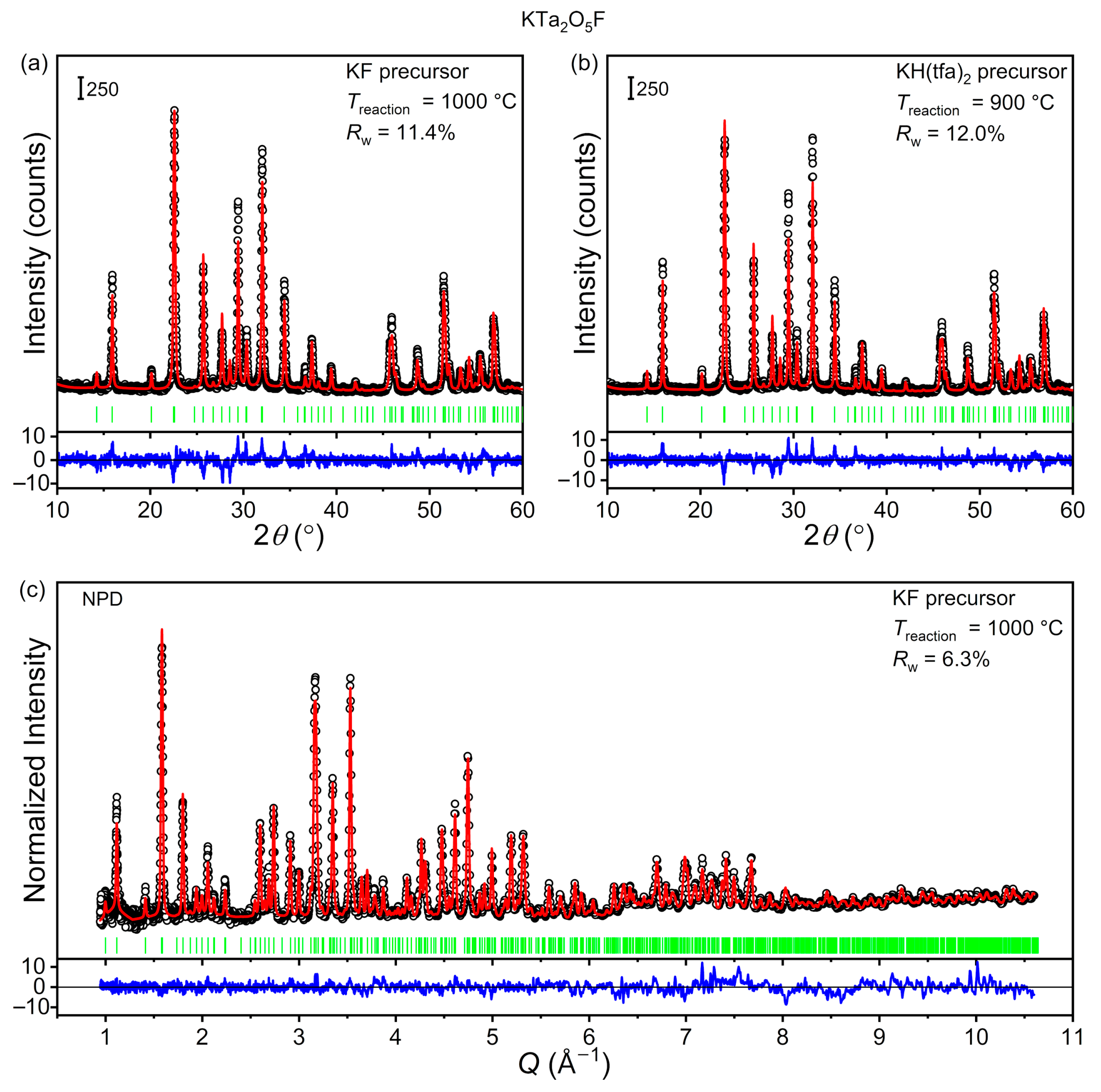

Synthesis optimization under ambient atmosphere was conducted by heating reaction mixtures in a box furnace, as described in the Experimental section. Attempts at synthesizing single-phase oxyfluorides began with KTa

2O

5F as the target phase. Results from successful attempts are given in

Figure 3, while those from control experiments are given in the

Supporting Information (Figure S1). Phase-pure KTa

2O

5F was obtained upon heating KF + Ta

2O

5 and KH(tfa)

2 + Ta

2O

5 mixtures at 1000 °C and 900 °C, respectively; using lower reaction temperatures led to the formation of a minor secondary phase (

Figure S1). The phase-purity of the polycrystalline solids was demonstrated via Rietveld analysis of PXRD data, which showed that all diffraction maxima belong to KTa

2O

5F (

Figure 3a,b). Structural refinements were conducted as described in the Experimental section, with the only difference being that atomic coordinates were refined for metal sites only; coordinates of oxygen/fluorine sites were fixed at their initial values. The resulting structural parameters are given in the

Supporting Information (Table S2). Refined atomic coordinates of metal sites showed minimal variation relative to their initial values. On the other hand, occupancies of the K1 and K2 sites changed significantly; these values went from 0.5 and 1.0, respectively, to 0.89 and 0.8 (KF precursor) and to 0.99 and 0.75 (KH(tfa)

2 precursor). Similar changes were observed when refining the isomorphous oxyfluoride KNb

2O

5F and were attributed to the impact of differing synthetic conditions on potassium disorder [

15]. Despite all diffraction maxima being indexed to the targeted oxyfluoride phase, our attention was drawn to the numerous intensity misfits. Attempts to remediate these misfits by refining the atomic coordinates of the oxygen/fluorine sites led to unreasonable values for tantalum–oxygen/fluorine distances. On this basis, and considering that there were no entries for KTa

2O

5F in crystallographic databases, we decided to carry out neutron diffraction studies. Room-temperature TOF–NPD data was collected for a KTa

2O

5F sample prepared at 1000 °C using KF as the potassium precursor. Next, Rietveld analysis was conducted to fit the starting structural model of KTa

2O

5F to the resulting NPD pattern. A full refinement was carried out, as described in the Experimental section. This included both metal and oxygen/fluorine atomic positions; only oxygen/fluorine site occupancies were fixed. Results from this analysis are given in

Figure 3c and the corresponding refined structural parameters are provided in

Table 2. Unlike what we observed when analyzing PXRD data, the experimental and calculated patterns were in excellent agreement. Further, the refined atomic positions translated into meaningful metal–oxygen/fluorine distances (K–O/F: 2.80–3.32 Å; Ta–O/F: 1.94–1.99 Å). Therefore, we concluded that the tetragonal tungsten bronze model of KTa

2O

5F provides an accurate structural description of this material.

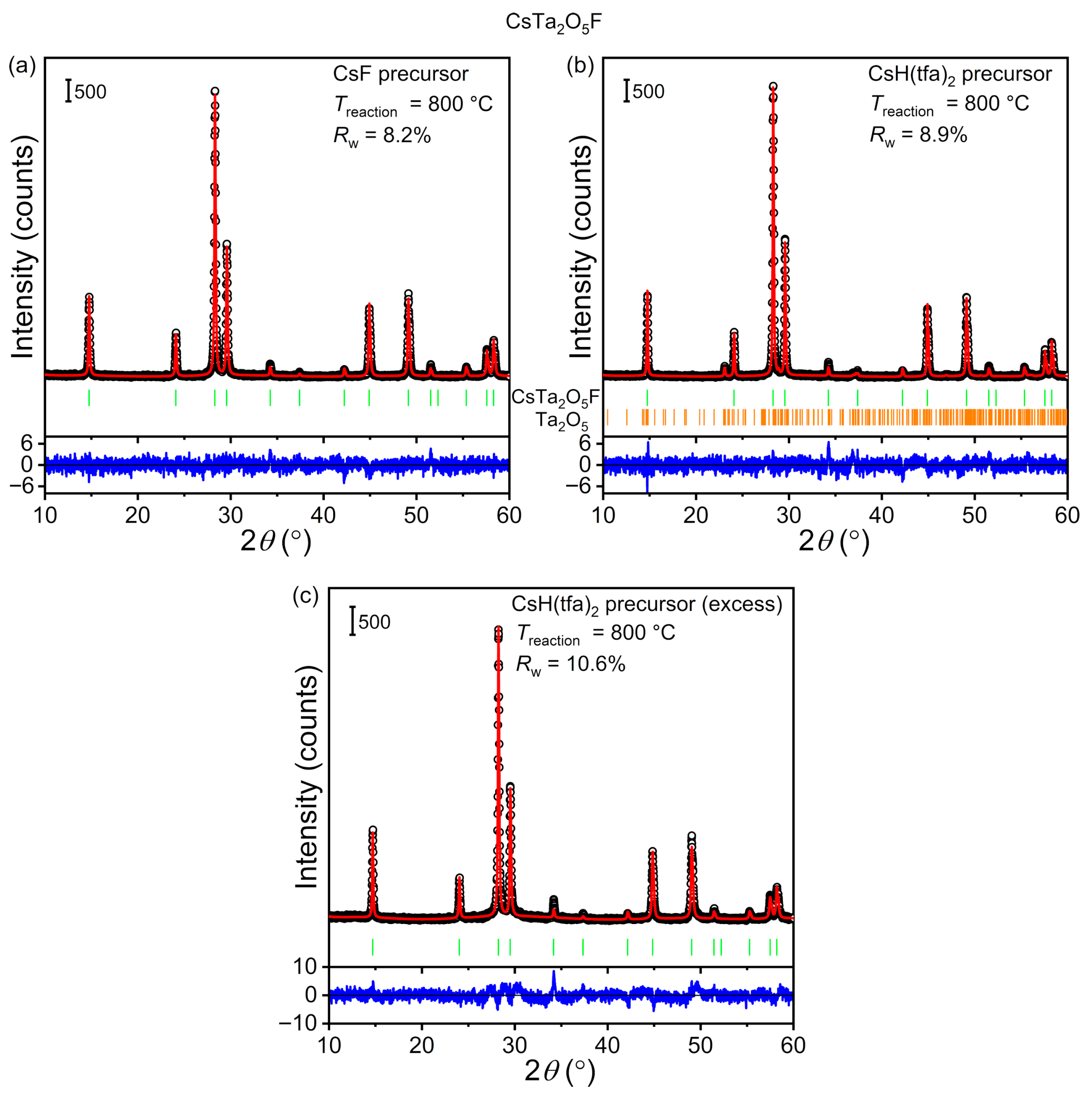

Having successfully synthesized KTa

2O

5F using both potassium fluoride and trifluoroacetate precursors, we moved forward aiming to synthesize single-phase CsTa

2O

5F. Results from the most successful attempts are given in

Figure 4, while those from control experiments are given in the

Supporting Information (Figure S2). Phase-pure CsTa

2O

5F was obtained upon heating CsF + Ta

2O

5 at 800 °C; using lower reaction temperatures resulted in unreacted Ta

2O

5 as a secondary phase (

Figure S2). Rietveld analysis of the corresponding PXRD pattern showed that all diffraction could be indexed to the pyrochlore phase CsTa

2O

5F (PDF No. 01–078–9470,

Figure 4a). The resulting structural parameters are given in the

Supporting Information (Table S3). Refined atomic coordinates of the oxygen/fluorine site showed minimal variation relative to their initial values. The preparation of single-phase CsTa

2O

5F using a stoichiometric CsH(tfa)

2 + Ta

2O

5 mixture proved more challenging. According to Rietveld analysis, conducting the reaction at 800 °C led to a mixture of CsTa

2O

5F (≈96 wt.%) and unreacted Ta

2O

5 (≈4 wt.%) (

Figure 4b). Attempts to get rid of that secondary phase by lowering the reaction temperature to 700 °C were unsuccessful (

Figure S2). Reaction temperatures above 800 °C were not explored because results from thermal analysis showed that unreacted Ta

2O

5 was present even after heating up to 1000 °C (vide supra). On this basis, we decided to tune the composition of the reaction mixture by adding an excess of CsH(tfa)

2 (Cs:Ta molar ratio = 1.1:2). Our hypothesis was that the inability to achieve a quantitative reaction between CsH(tfa)

2 and Ta

2O

5 was due to the fast volatilization of the former, which melts at ≈120 °C [

16]. Heating the non-stoichiometric mixture to 800 °C led to the formation of CsTa

2O

5F as the only crystalline phase observable via Rietveld analysis of PXRD (

Figure 4c). However, careful observation of the experimental pattern and of the difference curve in the angular range 26.5–32.0° showed that the background was noticeably more intense than for solids prepared using stoichiometric mixtures. Thus, although CsTa

2O

5F was the only observable crystalline phase, the presence of a non-negligible amount of amorphous (or nanocrystalline) matter could not be ruled out.

3. Materials and Methods

Synthesis of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 Precursors. Polycrystalline KH(tfa)

2 and CsH(tfa)

2 (tfa = CF

3COO) were synthesized via solvent evaporation [

15,

17,

18]. K

2CO

3 (99%), Cs

2CO

3 (99.9%), and anhydrous CF

3COOH (tfaH, 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and used as received. Double-deionized water was used as a cosolvent. 1 mmol of the corresponding metal carbonate (K

2CO

3 or Cs

2CO

3), 3 mL of double-deionized water, and 3 mL of tfaH were mixed in a 50 mL two-neck round-bottom flask. The resulting colorless transparent solution was immersed in a sand bath and heated at 65 °C for 24 h (potassium) and 48 h (cesium) under a constant flow of 140 mL min

−1 of N

2. White polycrystalline solids were thus obtained.

Synthesis of KTa2O5F and CsTa2O5F. KTa2O5F and CsTa2O5F were synthesized via solid-state reaction under air (relative humidity 25–65%). Starting materials included KF (99%), CsF (99%), and Ta2O5 (99.99%) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received, and KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 prepared in-house (vide supra). KF + Ta2O5, KH(tfa)2 + Ta2O5, CsF + Ta2O5, and CsH(tfa)2 + Ta2O5 reaction mixtures were prepared by mixing and grinding stoichiometric amounts of starting materials in an agate mortar in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. ≈100 mg of each mixture were transferred to 5 mL alumina crucibles, covered with alumina disks, removed from the glovebox, and quickly placed inside a box furnace at 100 °C. Reaction mixtures were then heated under air to the target reaction temperature (Treaction, 600–1000 °C) at a rate of 10 °C min−1 for 1 h. After heating, the furnace was allowed to cool to ≈400 °C, and the crucibles were removed. A total of five heating cycles were carried out, with intermediate grindings between each cycle performed under air. Polycrystalline white powders were thus obtained. Phase-pure KTa2O5F and CsTa2O5F were obtained upon heating KF + Ta2O5 and KH(tfa)2 + Ta2O5 mixtures at 1000 °C and 900 °C, respectively, and CsF + Ta2O5 at 800 °C.

Thermal Analysis (TGA–DTA). Thermogravimetric (TGA) and differential thermal (DTA) analyses of reaction mixtures KF + Ta2O5, KH(tfa)2 + Ta2O5, CsF + Ta2O5, and CsH(tfa)2 + Ta2O5 were conducted under dry synthetic air (100 mL min−1) using a TGA–DTA analyzer (SDT2960, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). ≈35–65 mg of sample were placed in an alumina crucible, held at 35 °C for 10 min, and then ramped to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1. Heating was stopped once the temperature reached 1000 °C and samples were allowed to cool to room temperature.

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD). PXRD patterns were collected using a D2 Phaser diffractometer operated at 30 kV and 10 mA (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) was employed. A nickel filter was used to remove Cu Kβ radiation. Diffractograms were collected in the 10–60° 2θ range using a step size of 0.012° and a step time of 0.4 s, unless otherwise noted.

Time-of-Flight Neutron Powder Diffraction (TOF–NPD). Neutron diffraction data were collected using the POWGEN diffractometer of the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Oak Ridge, TN, USA). ≈700 mg of KTa2O5F were loaded into a 6 mm diameter vanadium can. A TOF–NPD pattern was collected at 300 K with the high-resolution setting and a center wavelength of 0.8 Å in the 3.6–176 ms time window. Raw diffraction data was processed using POWGEN’s autoreduction software.

Rietveld Analysis. Rietveld analysis [

19,

20] of PXRD and NPD data was conducted using GSAS-II (version 5.6.4) [

21]. Initial structural parameters of KTa

2O

5F and CsTa

2O

5F are given in the

Supporting Information (Table S1). In the case of X-ray diffraction data, the following parameters were refined: (1) scale factor and sample displacement; (2) background, which was modeled using a shifted Chebyschev polynomial function; (3) lattice constants; (4) atomic coordinates of metal atoms when allowed by space-group symmetry; (5) one isotropic atomic displacement parameter (

Uiso) for each type of atom in the structure, constrained to

UisoK = 1.2 ×

UisoTa and

UisoO/F = 1.5 ×

UisoTa in KTa

2O

5F and to

UisoO/F = 1.5 ×

UisoCs = 1.5 ×

UisoTa in CsTa

2O

5F; (6) occupancy factors (

f) of K1 and K2 sites constrained to 2 ×

fK1 + 4 ×

fK2 = 5; and (7) crystallite size and microstrain. Occupancy factors of the oxygen/fluorine sites were fixed. In the case of neutron diffraction data, the following parameters were refined for KTa

2O

5F: (1) scale factor; (2) background, which was modeled using a logarithmic interpolation function; (3) instrument parameters, including diffractometer constant and contributions to peak profile; (4) lattice constants; (5) atomic positions when allowed by space-group symmetry; (6) an isotropic displacement parameter for each site in the structure; (7) occupancy factors (

f) of K1 and K2 sites constrained to 2 ×

fK1 + 4 ×

fK2 = 5; and (8) crystallite size and microstrain. Occupancy factors of the oxygen/fluorine sites were fixed. The quality of the refined structural models was assessed using the difference between the observed and calculated intensities divided by the standard uncertainty of the observed intensities (Δ(

I)/σ(

I)) and

Rw residuals. Crystal structures were visualized using VESTA (version 3.90.5a) [

22].