Unveiling the Phase Formations in the Sr–Zn–Eu3+ Orthophosphate System: Crystallographic Analysis and Photoluminescent Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

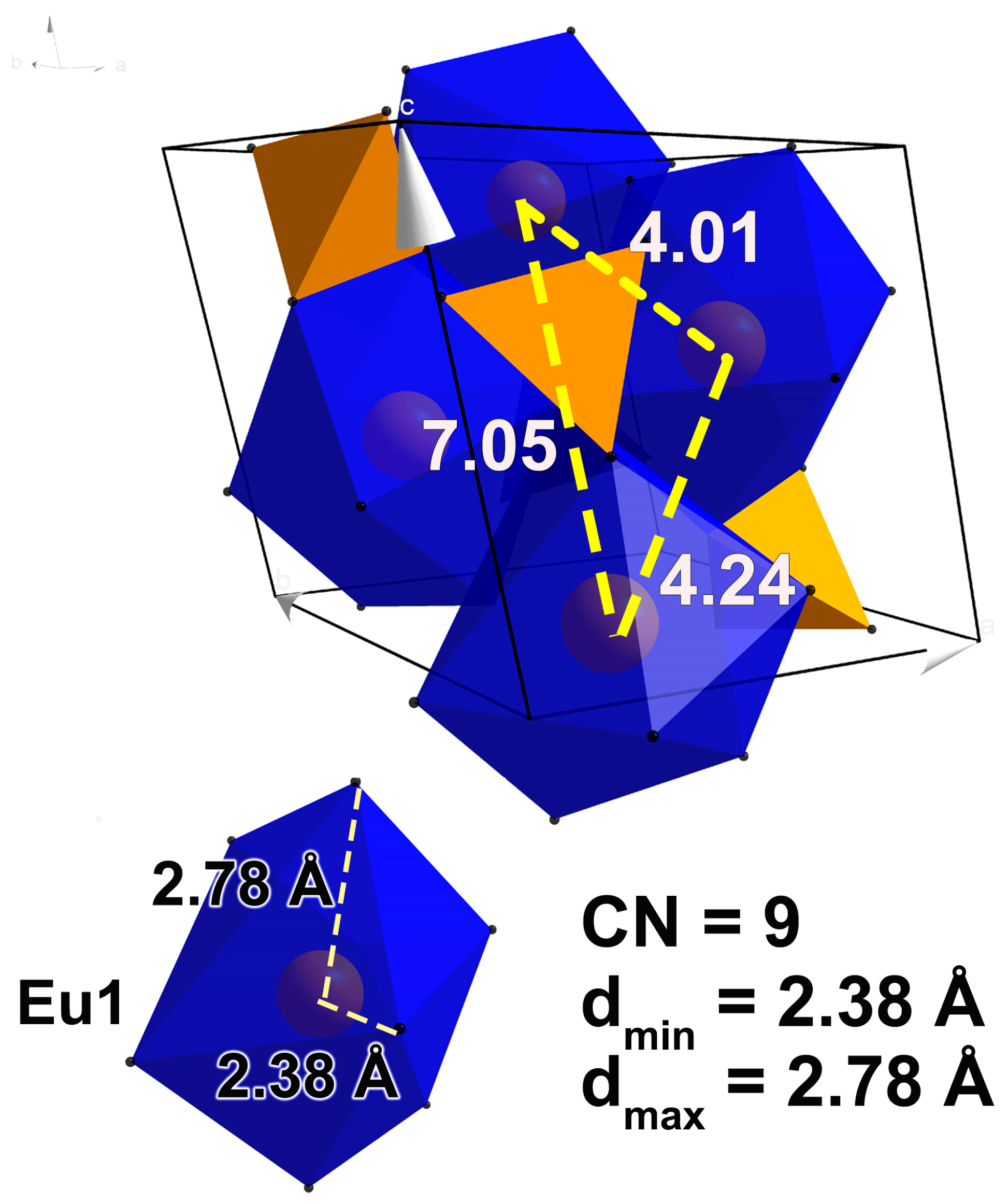

1.1. Monazite EuPO4

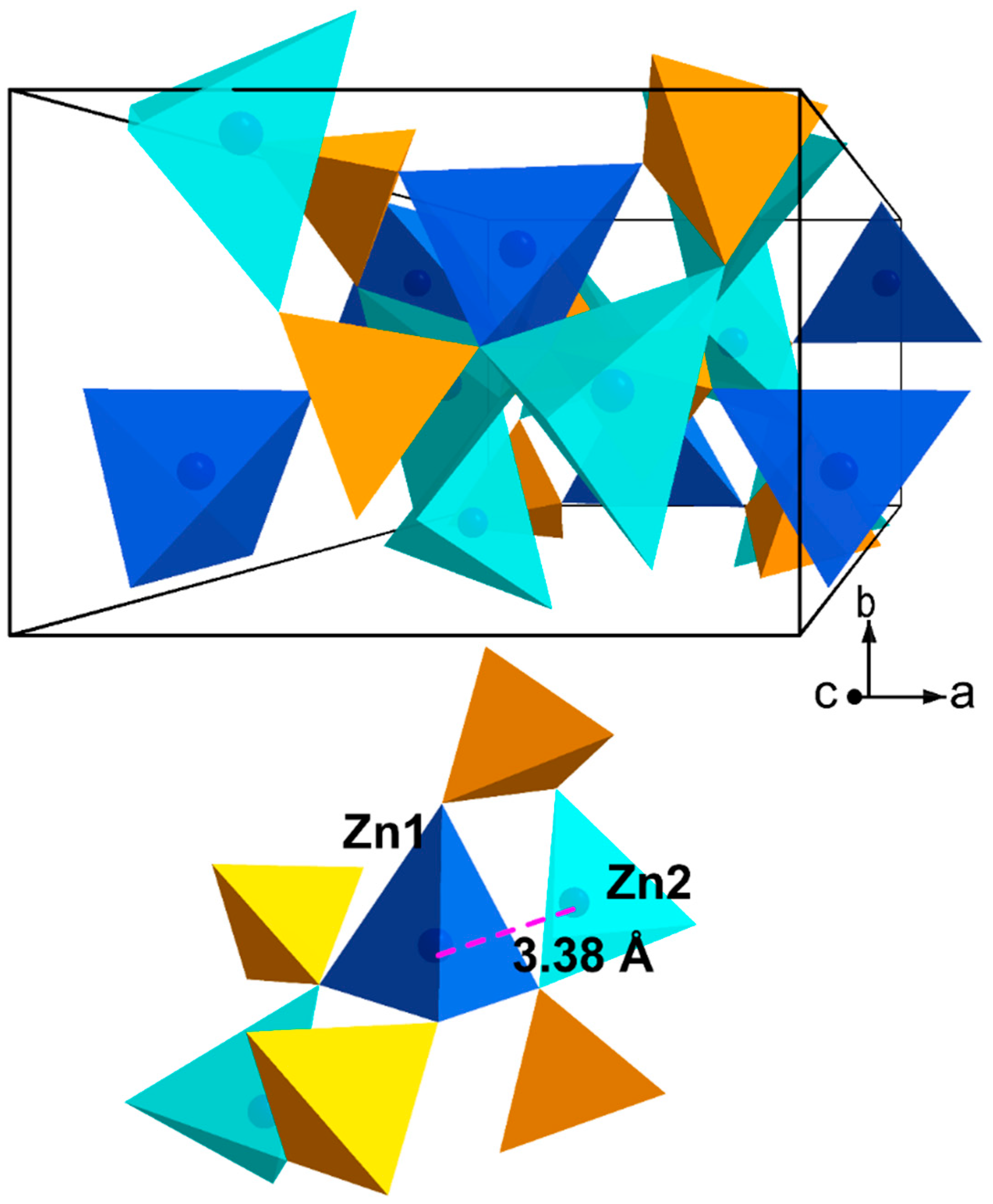

1.2. Hopeite α-Zn3(PO4)2

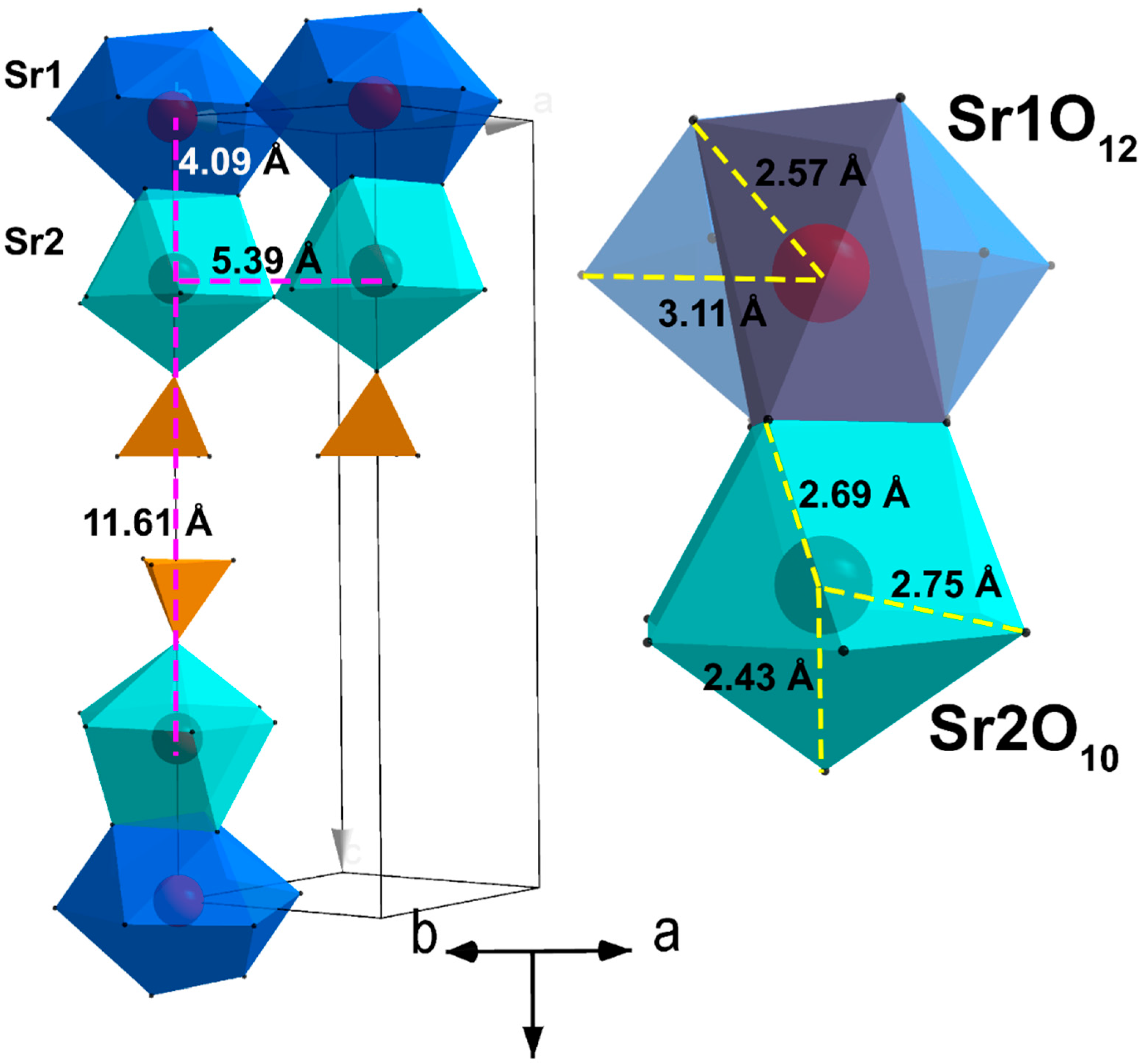

1.3. Palmierite α-Sr3(PO4)2

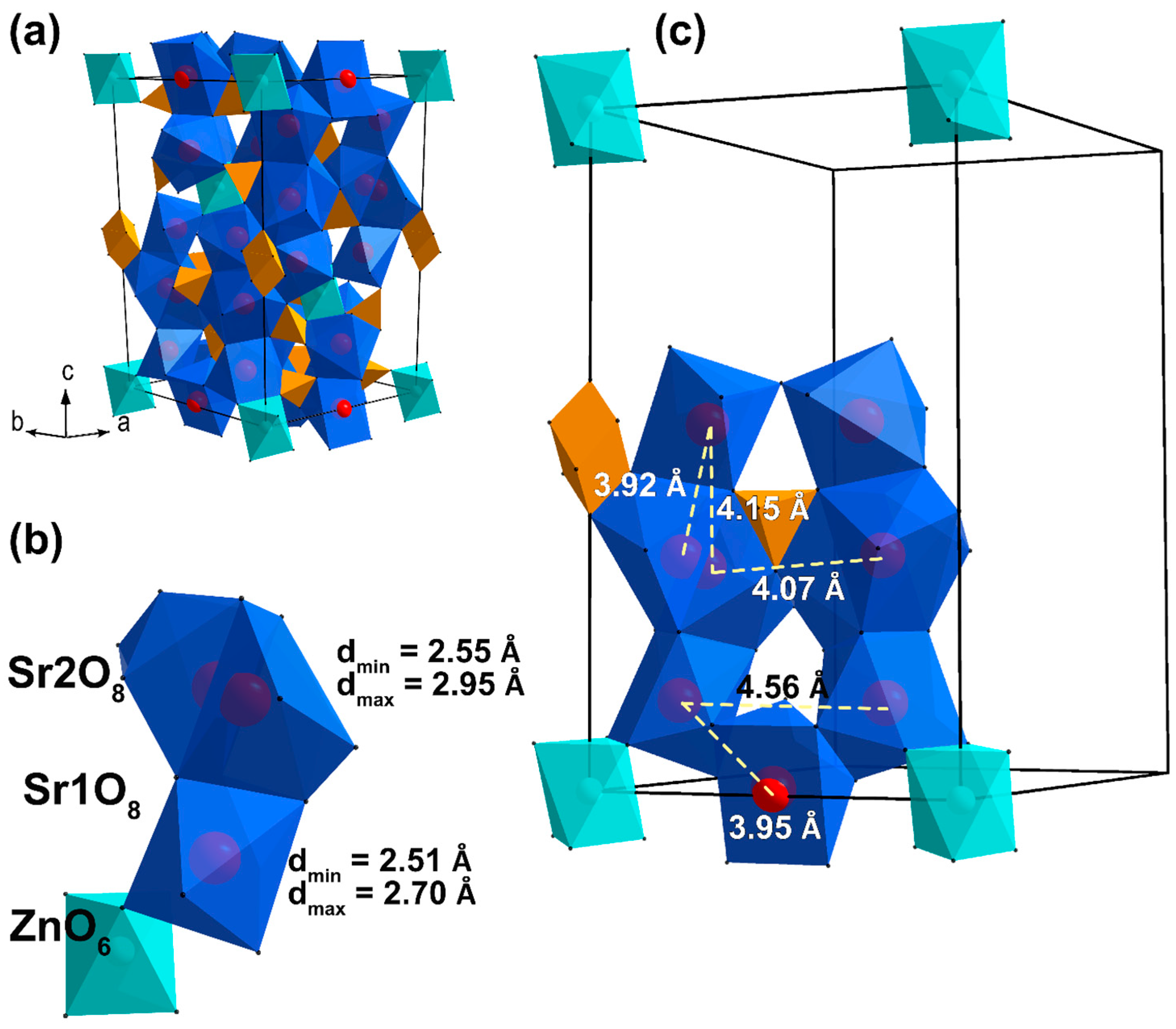

1.4. Strontiowhitlockite β-Sr3(PO4)2

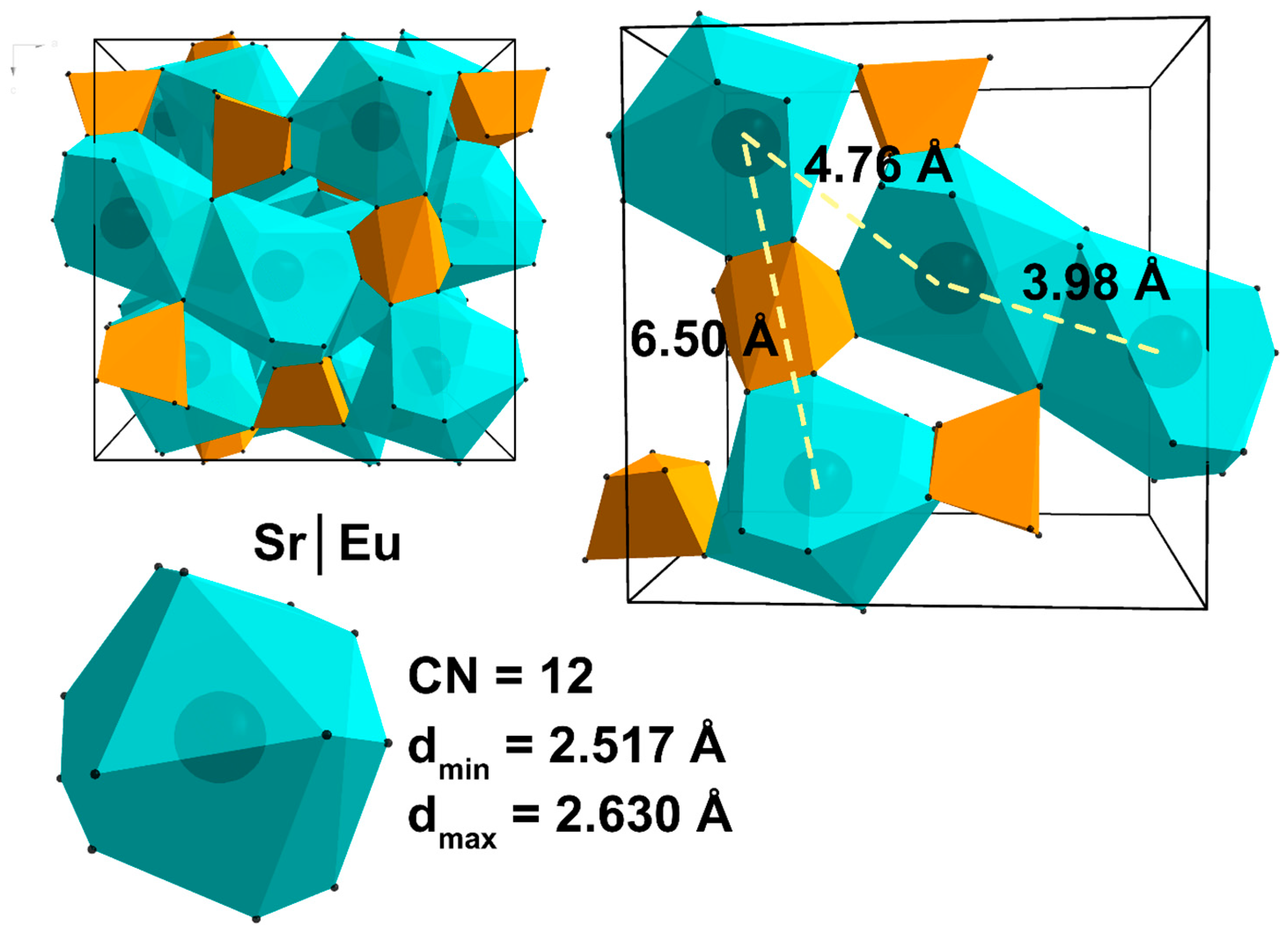

1.5. Eulytite Sr3Eu(PO4)3

1.6. Strontiohurlbutite SrZn2(PO4)2

2. Results and Discussion

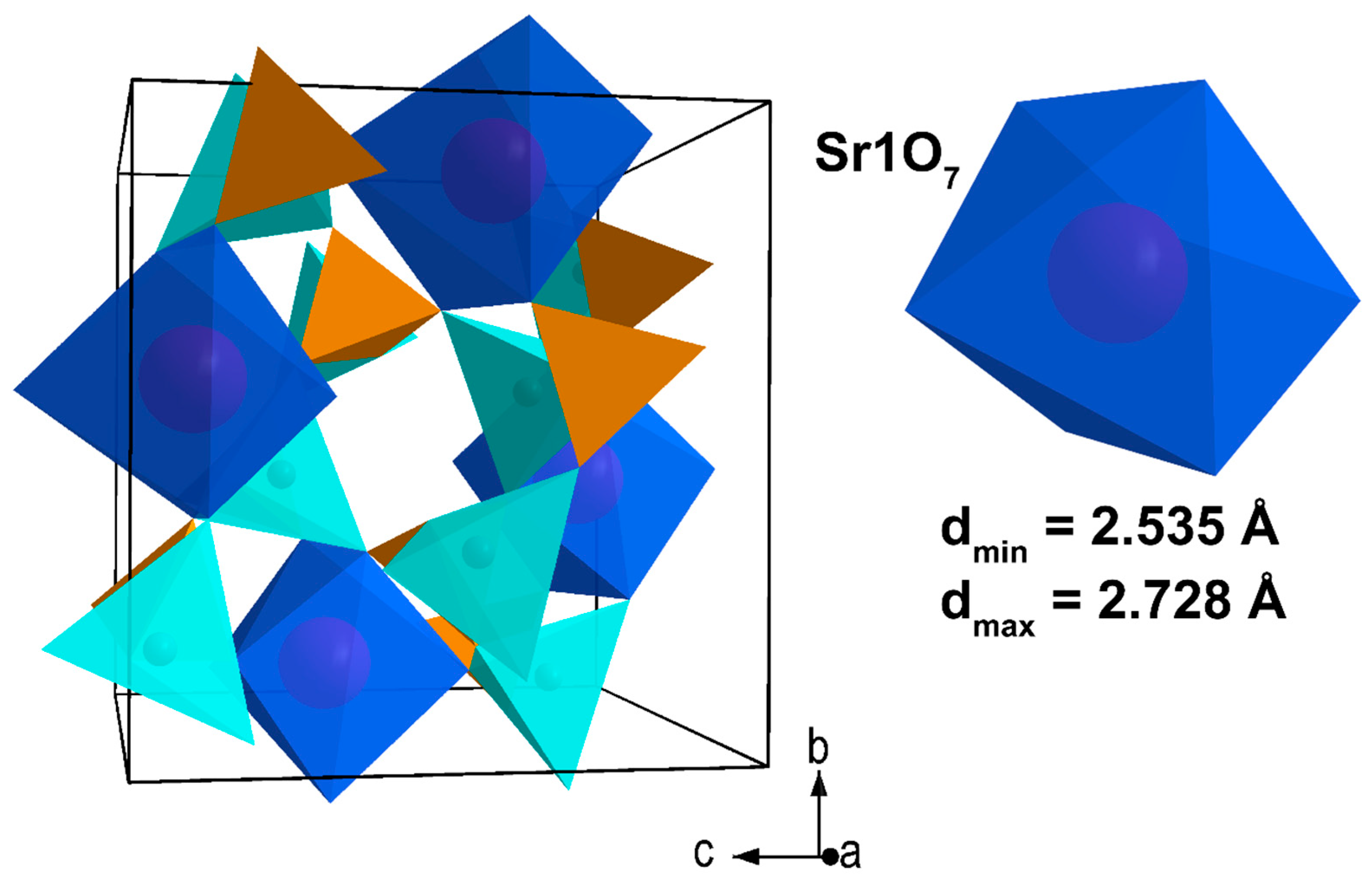

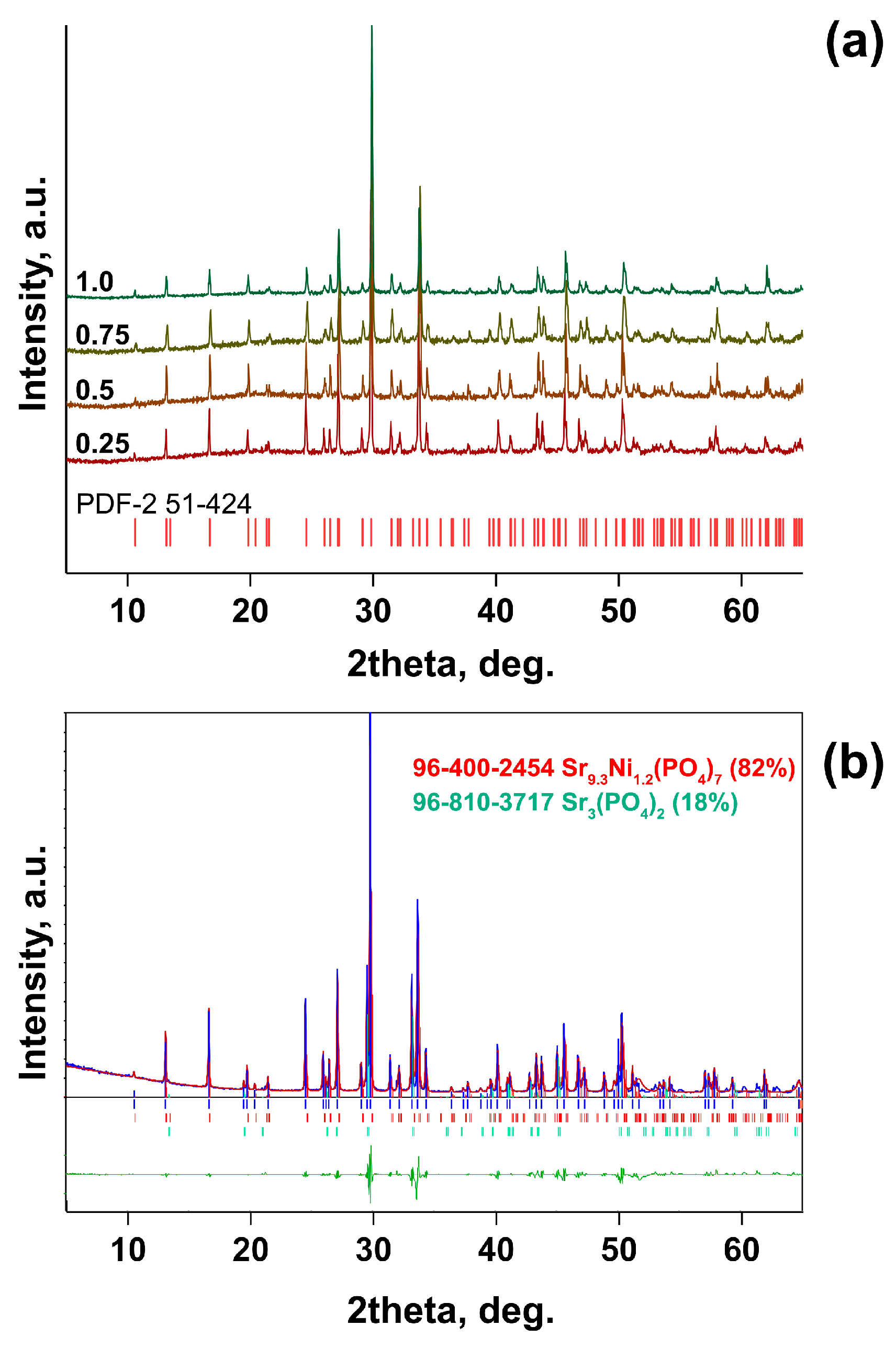

2.1. Substitution Sr2+ → Zn2+

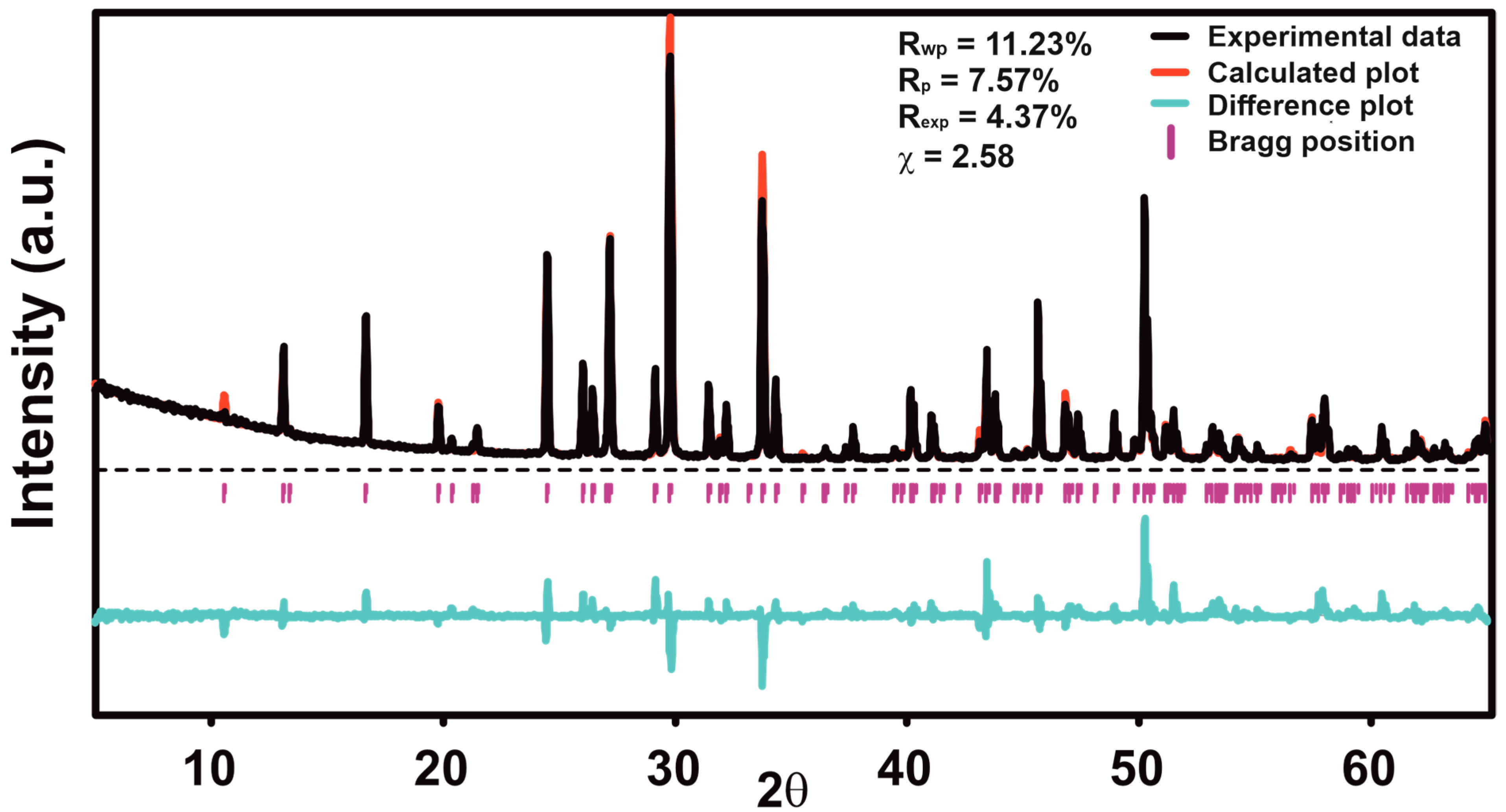

2.1.1. Rietveld Refinement

2.1.2. Combinatorial Complexity Calculations

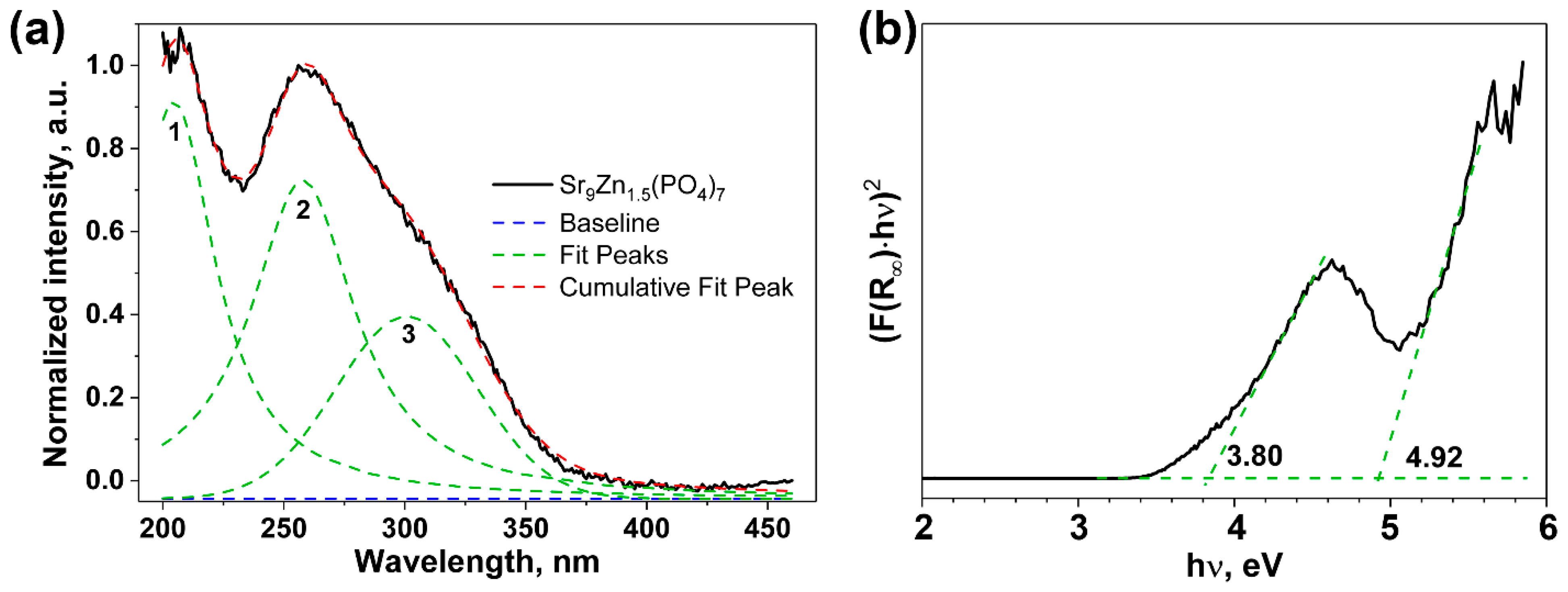

2.1.3. DRS Study

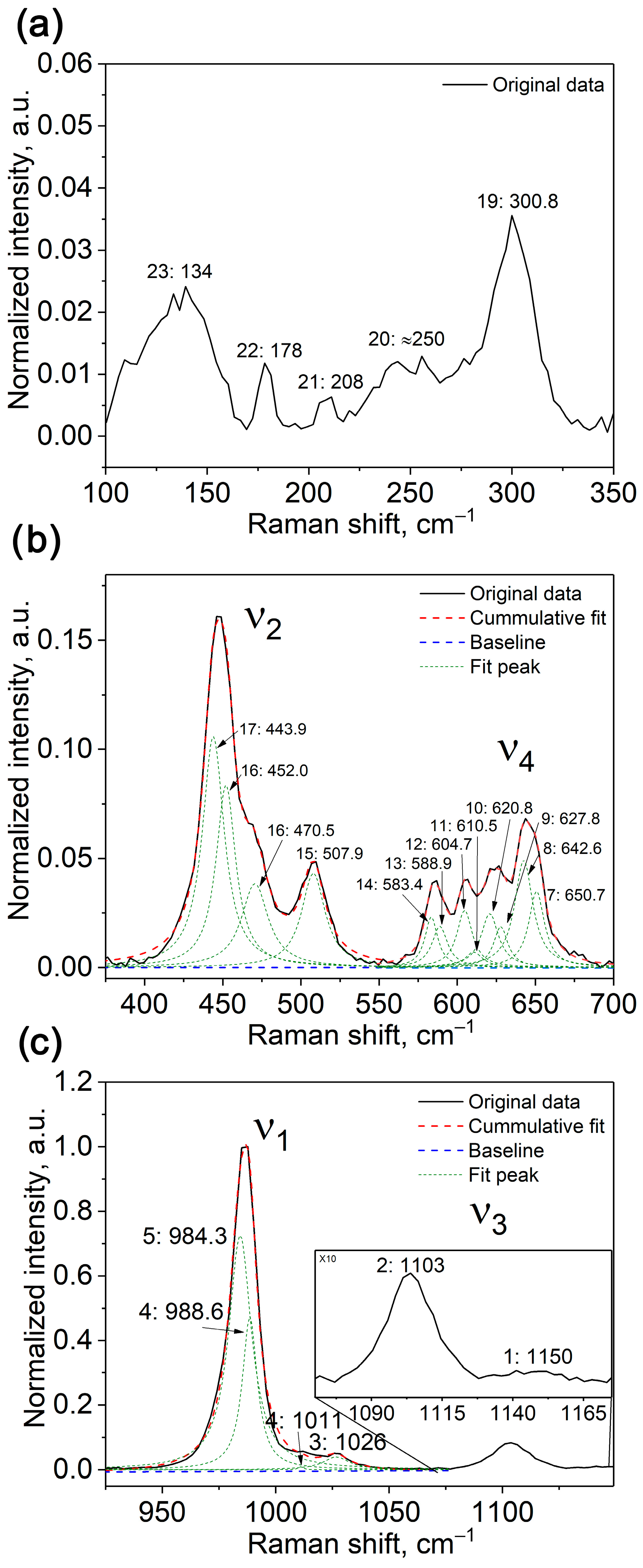

2.1.4. Raman Spectroscopy Study

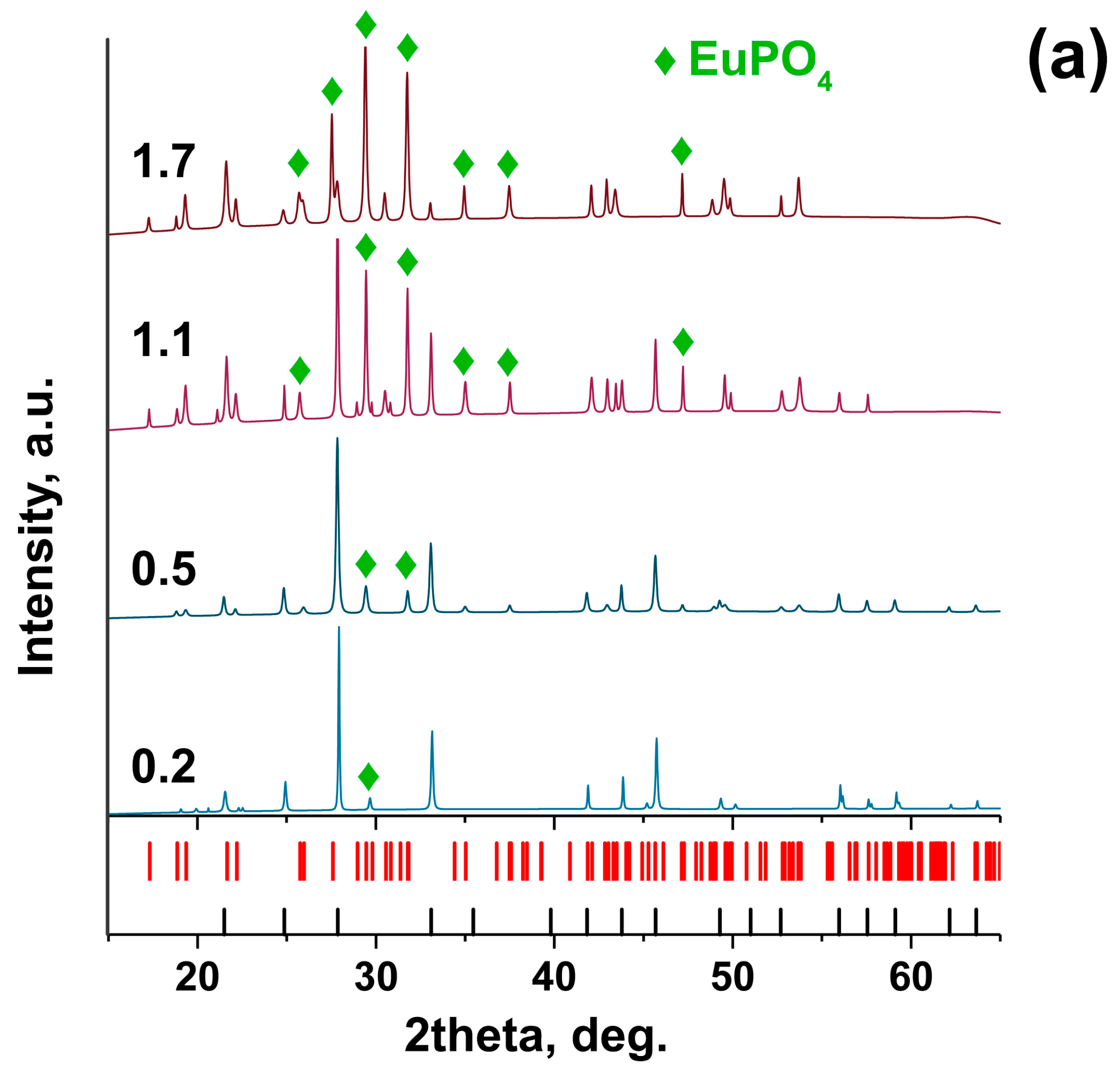

2.2. Substitution Sr2+ → Eu3+

2.3. Co-Substitution Sr2+ → Zn2+, Eu3+

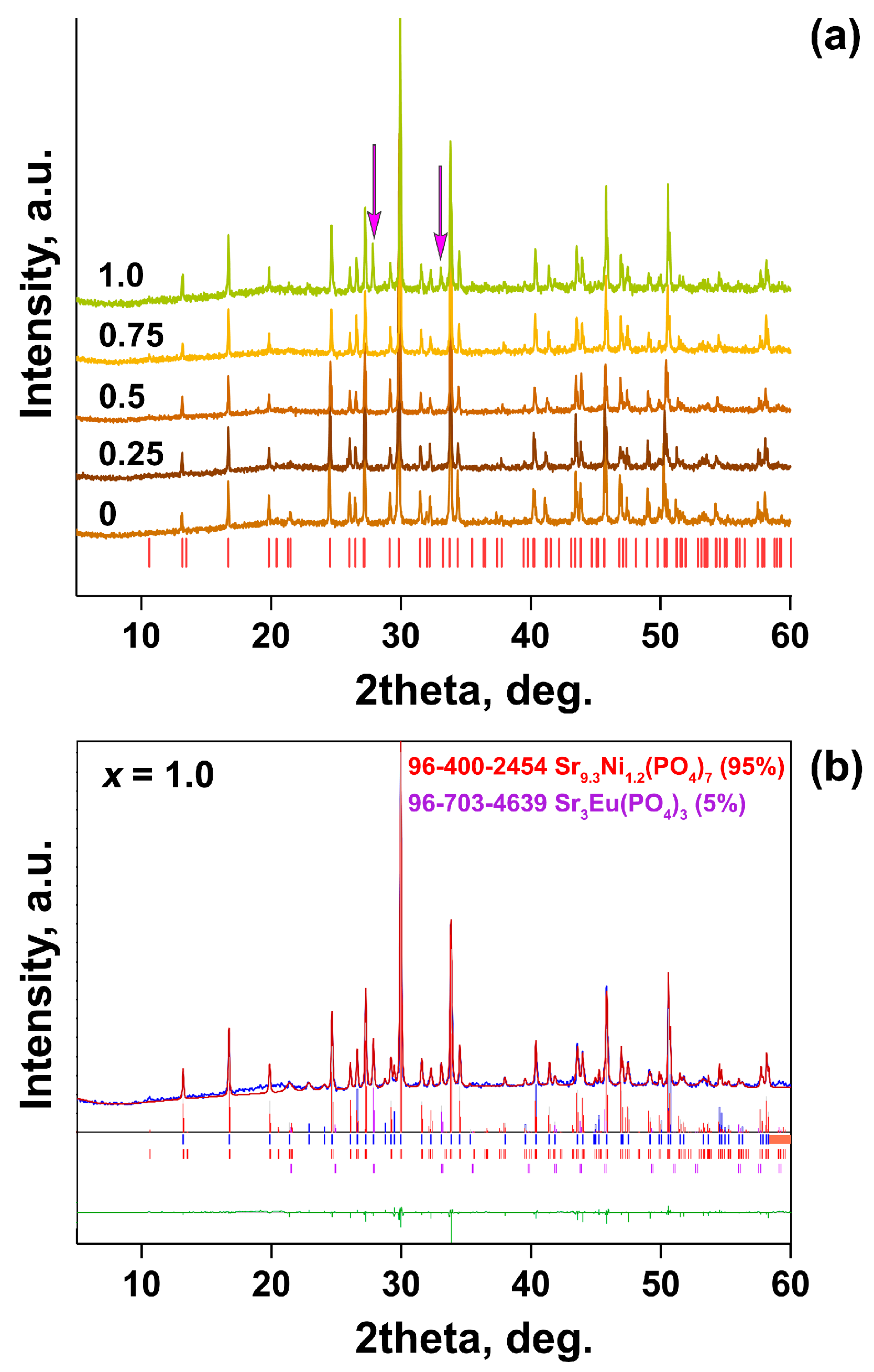

2.3.1. Sr9–xZnxEu(PO4)7

2.3.2. Sr9.5–1.5xZnEux(PO4)7

2.3.3. Sr9–1.5xZn1.5Eux(PO4)7

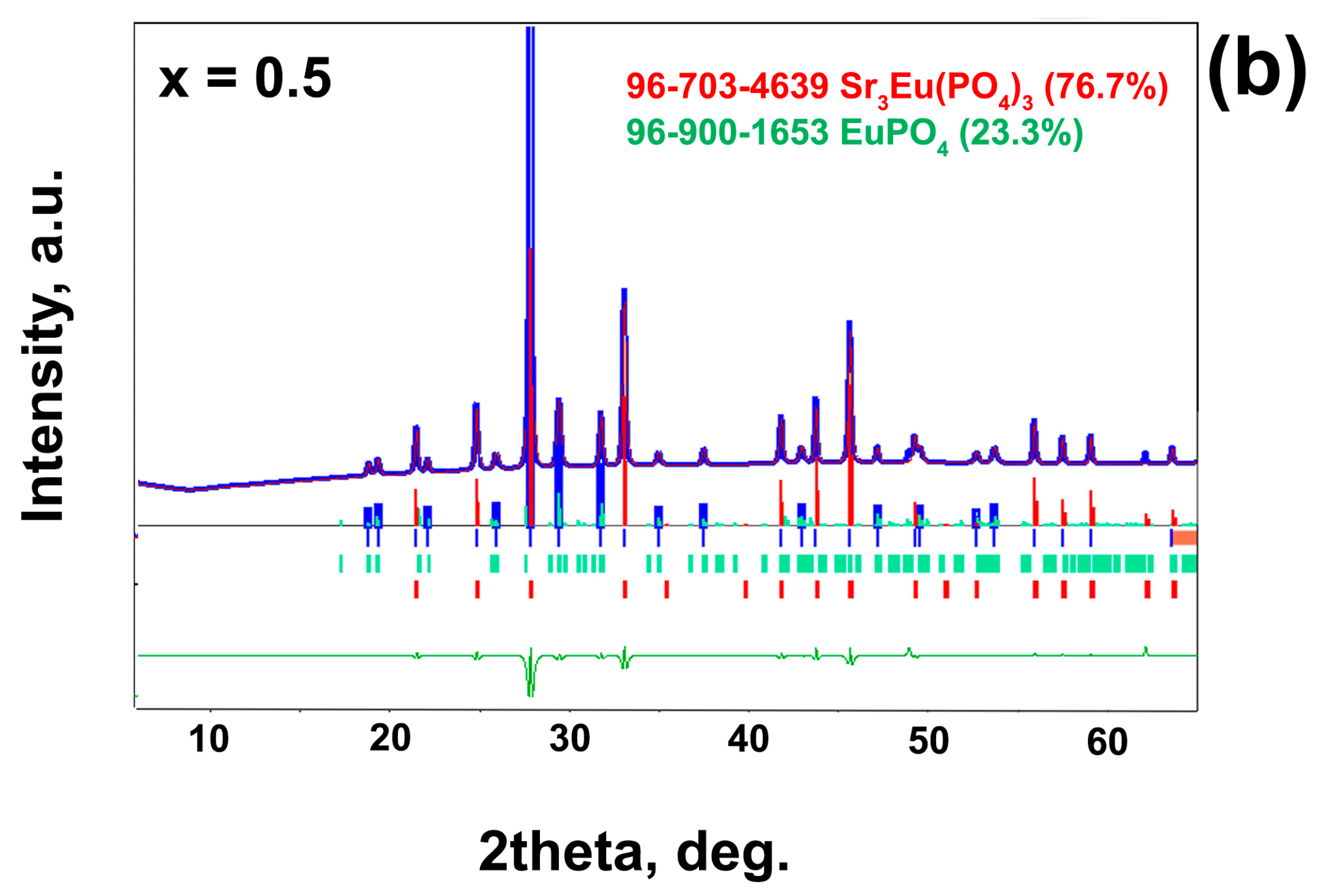

2.3.4. Sr3–xZnxEu(PO4)3

2.3.5. The SHG Test for Co-Substitution Sr2+ → Zn2+, Eu3+ Phosphates

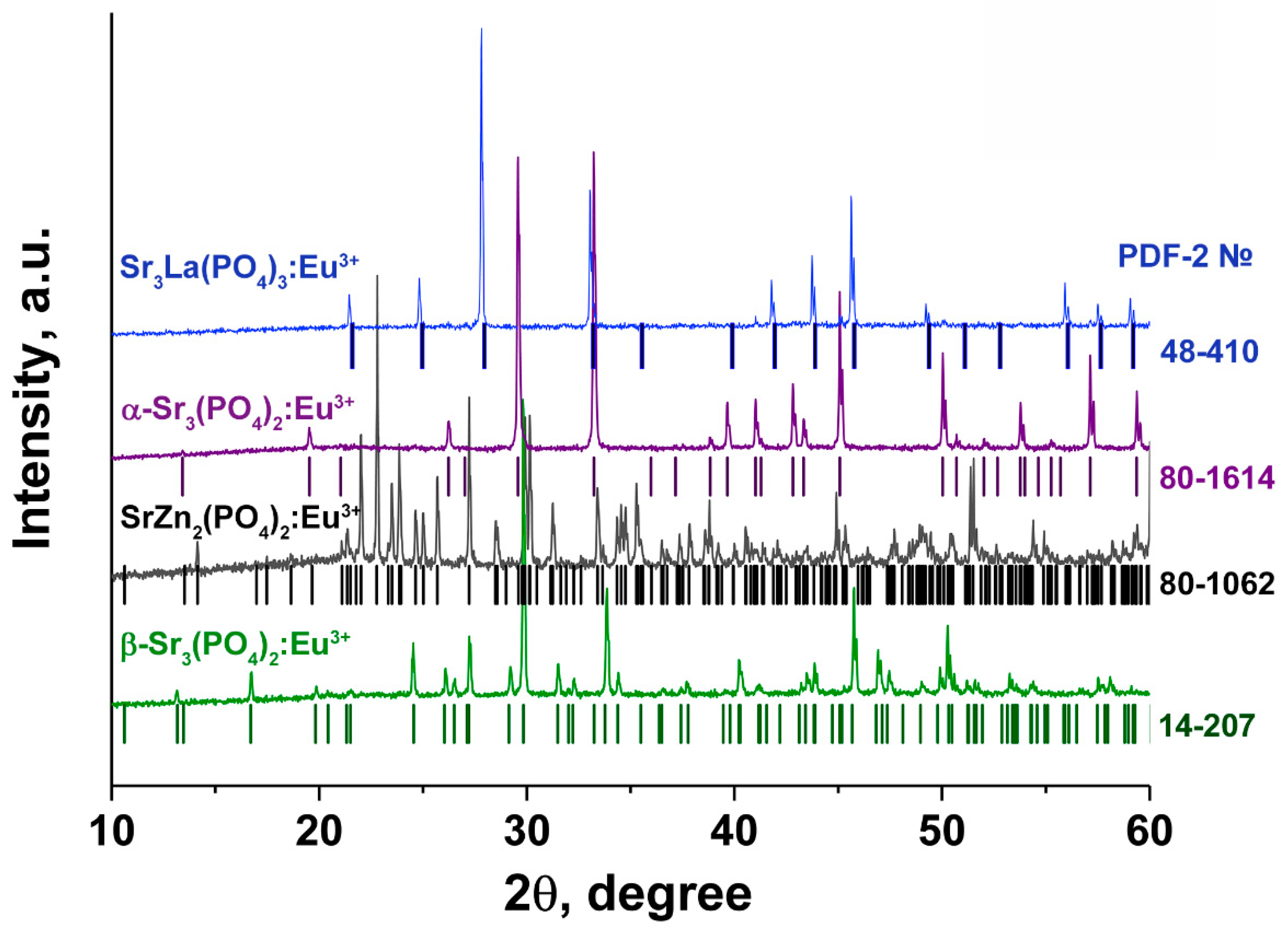

2.4. Eu3+ Doping of the Described Hosts

2.5. PL Study

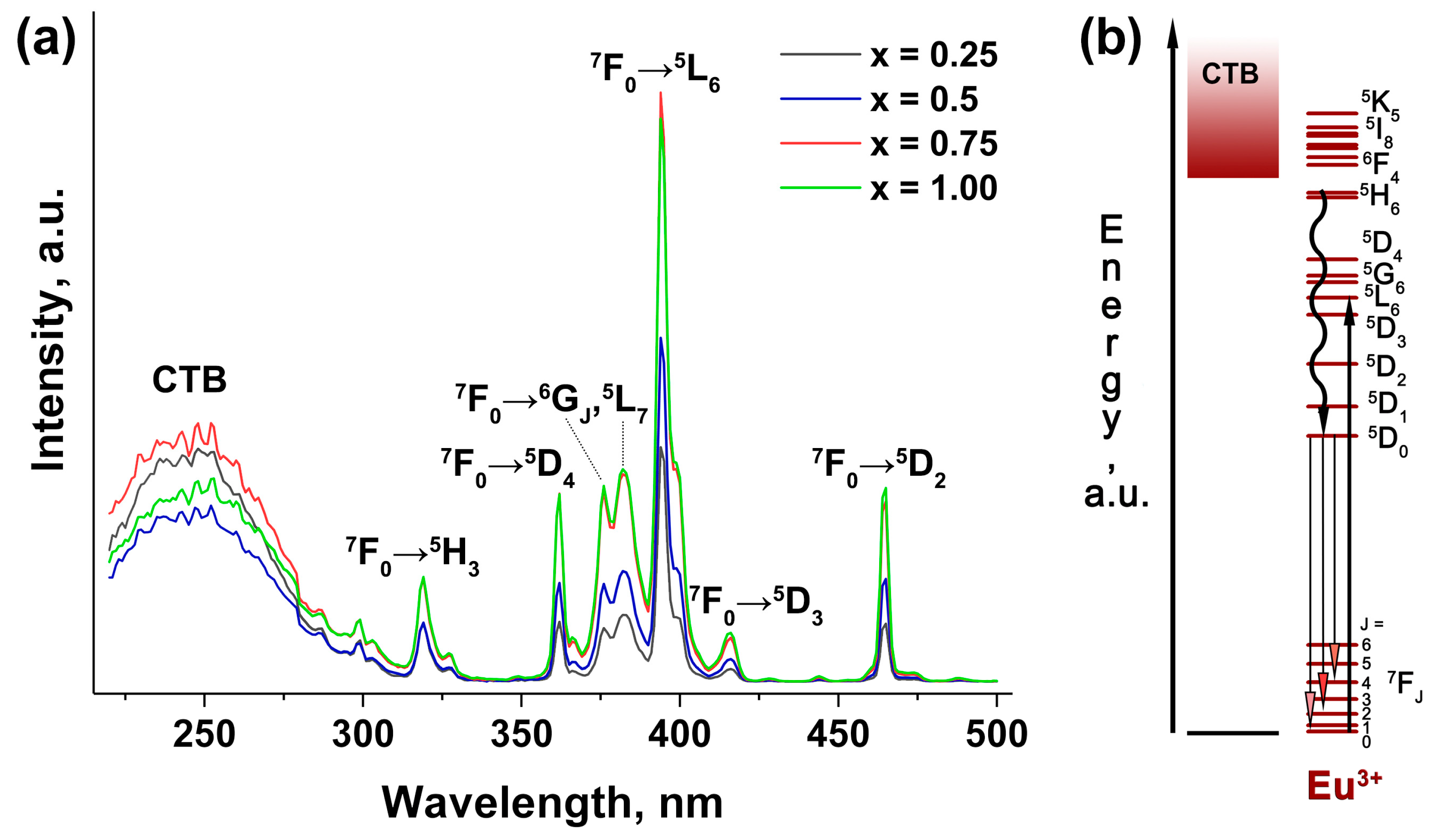

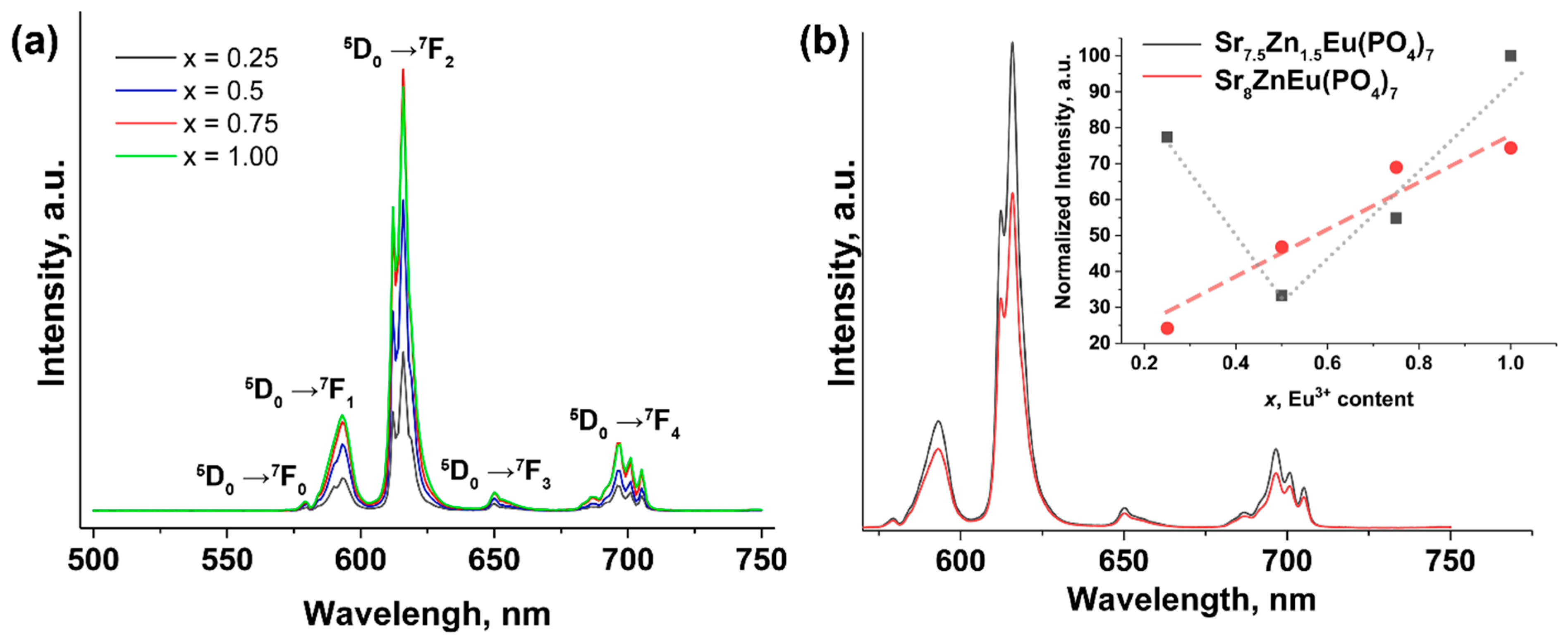

2.5.1. PL Study for Co-Substituted Sr2+ → Zn2+, Eu3+ Phosphates

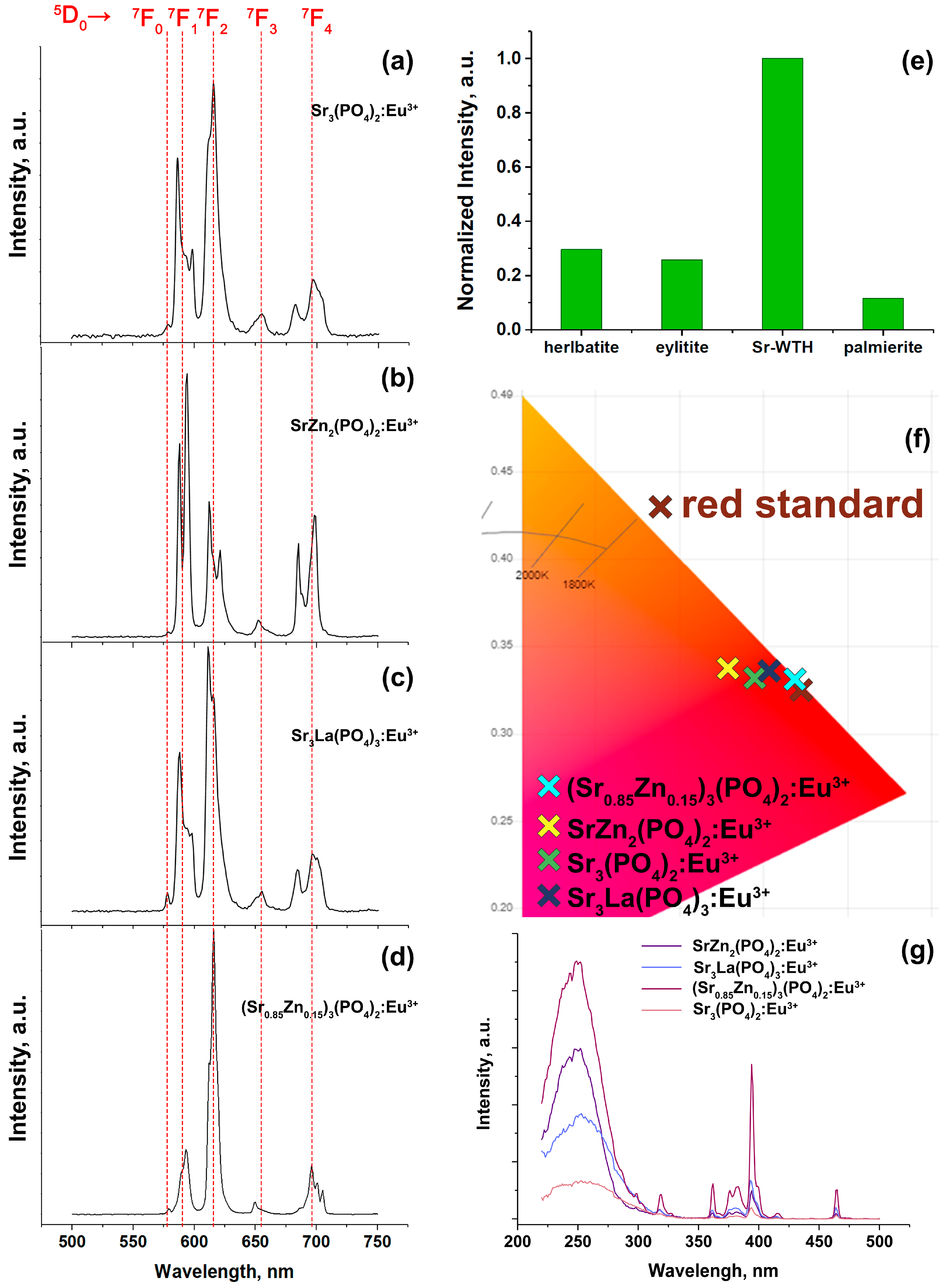

2.5.2. PL Study of Eu3+-Doped Hosts

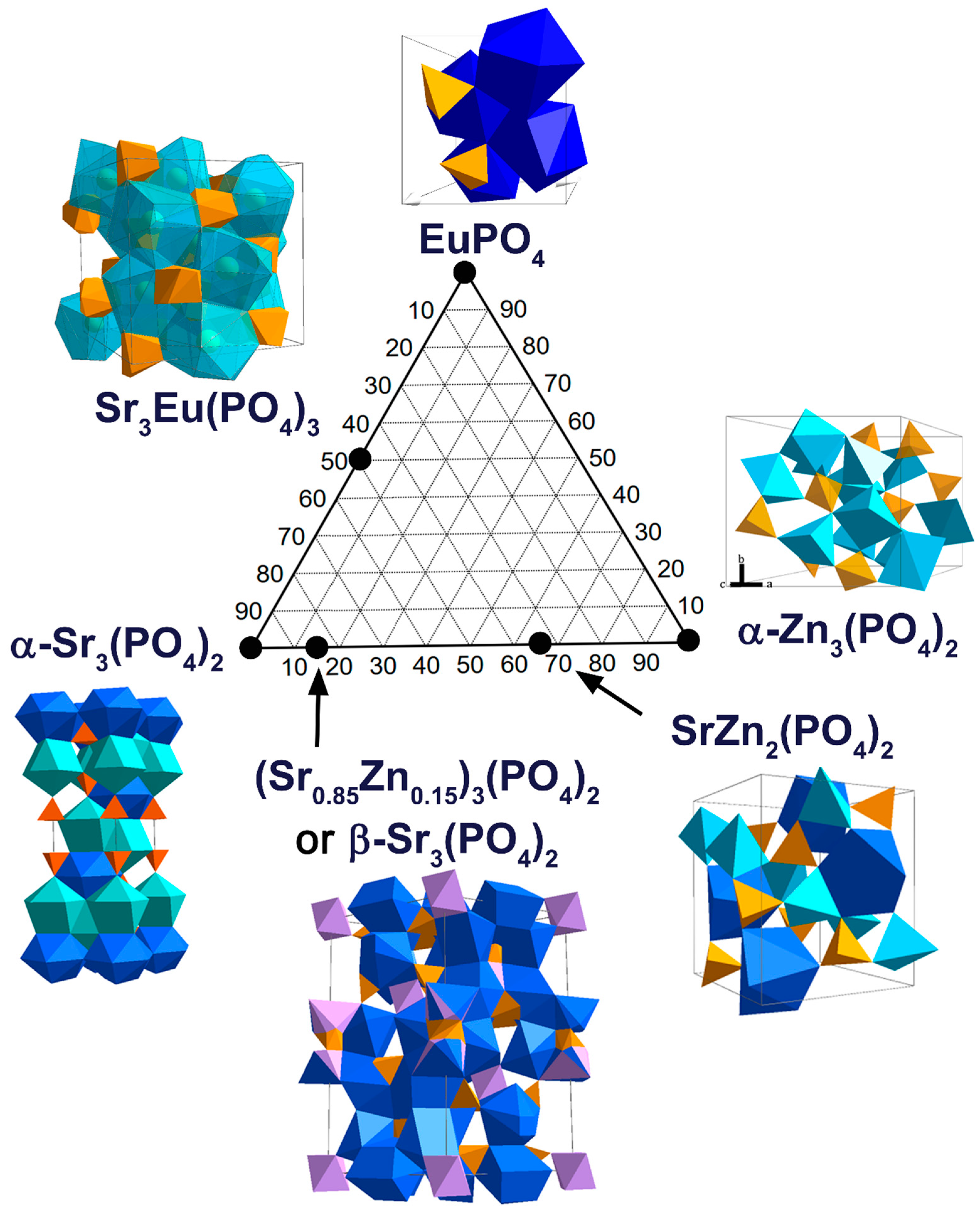

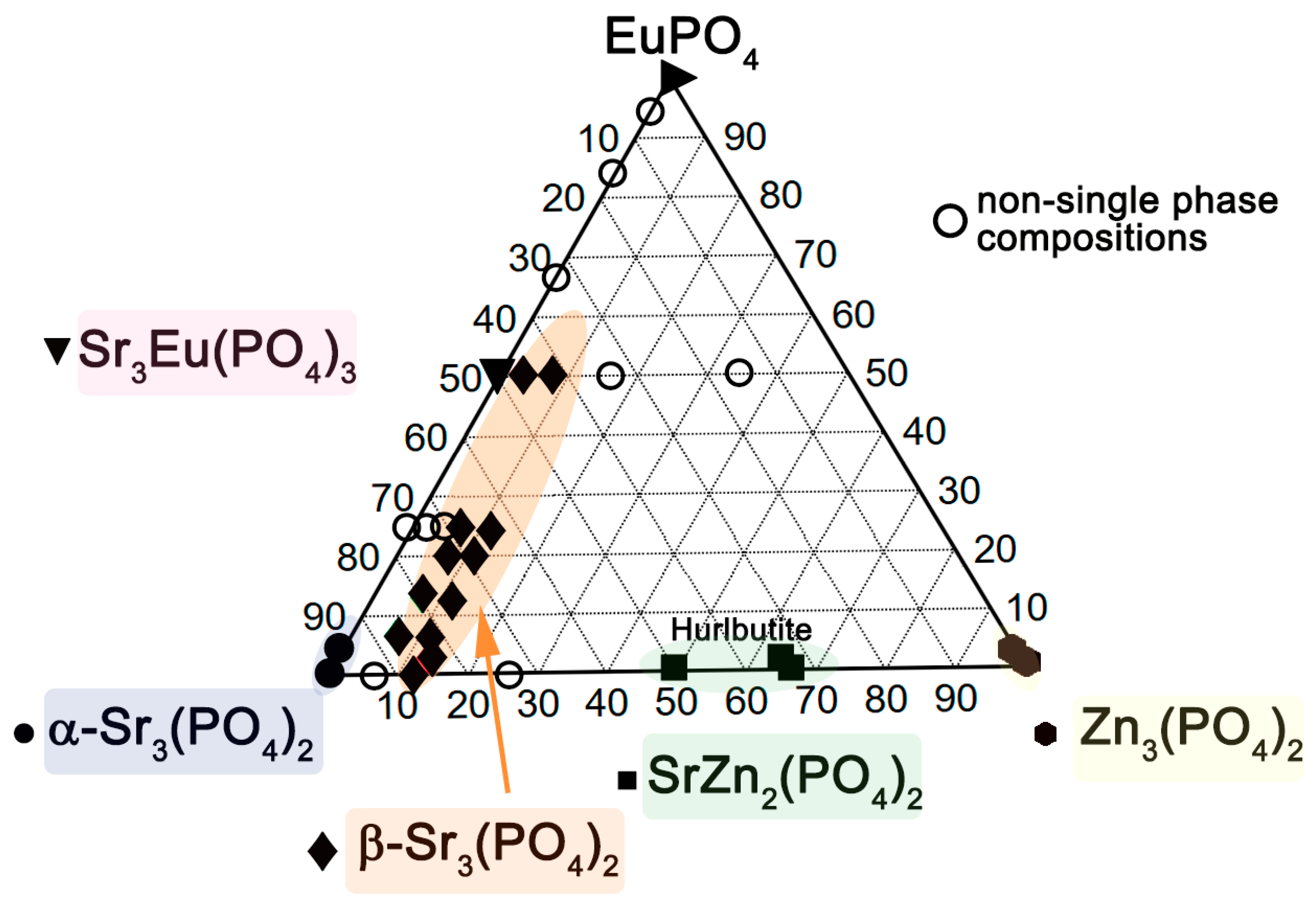

2.6. Phase Diagram in the Sr3(PO4)2–Zn3(PO4)2–EuPO4 System

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

| Substitution Type | General Formula of the Series | Range of x |

|---|---|---|

| Sr2+ → Zn2+ | Sr3–xZnx(PO4)2 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 2.0 |

| Sr2+ → Eu3+ | Sr3–1.5xEu1+x(PO4)3 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 2.0 |

| Sr2+ → Zn2+, Eu3+ | Sr3–xZnxEu(PO4)3 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 2.0 |

| Sr9–xZnxEu(PO4)7 [54] | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1.5 | |

| Sr9.5–1.5xZnEux(PO4)7 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0 | |

| Sr9–1.5xZn1.5Eux(PO4)7 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0 | |

| Individual compositions | Sr0.985Zn2Eu0.01(PO4)2; Sr2.985Eu0.01(PO4)2; Sr2.535Zn0.45Eu0.01(PO4)2 Sr3La0.99Eu0.01(PO4)3 | x = 0.01 |

3.2. Methods of Investigation

3.2.1. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) Study

3.2.2. Second Harmonic Generation Study

3.2.3. Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy

3.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

3.2.5. Combinatorial Complexity

3.2.6. Photoluminescence Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sehrawat, N.; Devi, P.; Dalal, H.; Solanki, D.; Garg, O.; Kumar, M.; Punia, R.; Garg, S. Solution combustion derived color-tunable Eu3+ doped Ca8ZnBi(VO4)7 nano sample for luminous devices and latent fingerprinting applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 168, 112976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Spassky, D.A.; Berdonosov, P.S.; Dzhevakov, P.B.; Lazoryak, B.I. Sr8MSm1-xEux(PO4)7 phosphors derived by different synthesis routes: Solid state, sol-gel and hydrothermal, the comparison of properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 887, 161340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmiyas, J.; Benhsina, E.; Ouaatta, S.; Assani, A.; Saadi, M.; El Ammari, L. Crystal structure of silver strontium copper orthophosphate, AgSr4Cu4.5(PO4)6. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E 2020, 76, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Malakho, A.P.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Khasanov, S.S. Synthesis and X-ray Powder Diffraction Study of New Phosphates in the Cu3(PO4)2–Sr3(PO4)2 System: Sr1.9Cu4.1(PO4)4, Sr3Cu3(PO4)4, Sr2Cu(PO4)2, and Sr9.1Cu1.4(PO4)7. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 163, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Azuma, M.; Matsuo, A.; Whangbo, M.-H.; Koo, H.-J.; Kikuchi, J.; Kaji, T.; Okubo, S.; Ohta, H.; Kindo, K.; et al. Investigation of the Crystal Structure and the Structural and Magnetic Properties of SrCu2(PO4)2. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 6632–6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariasen, W. The crystal structure of the normal orthophosphates of barium and strontium. Acta Crystallogr. 1948, 1, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, J.H.; Jones, J.B. The crystal structure of hopeite. Am. Mineral. 1976, 61, 987–995. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, C. The Crystal Structure of α-Zn3(PO4)2. Can. J. Chem. 1965, 43, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begun, G.M.; Beall, G.W.; Boatner, L.A.; Gregor, W.J. Raman spectra of the rare earth orthophosphates. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1981, 11, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Hughes, J.M.; Mariano, A.N. Crystal chemistry of the monazite and xenotime structures. Am. Mineral. 1995, 80, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullica, D.F.; Milligan, W.O.; Grossie, D.A.; Beall, G.W.; Boatner, L.A. Ninefold coordination LaPO4: Pentagonal interpenetrating tetrahedral polyhedron. Inorganica Chim. Acta 1984, 95, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavier, N.; Podor, R.; Dacheux, N. Crystal chemistry of the monazite structure. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 941–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Xiao, X. Hydrothermal synthesis, controlled microstructure, and photoluminescence of hydrated Zn3(PO4)2: Eu3+ nanorods and nanoparticles. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2009, 11, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, Q.; Wang, S. A novel red long lasting phosphorescent (LLP) material β-Zn3(PO4)2:Mn2+, Sm3+. Mater. Res. Bull. 2005, 40, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzechnik, A.; McMillan, P.F. High Pressure Behavior of Sr3(VO4)2 and Ba3(VO4)2. J. Solid State Chem. 1997, 132, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazoryak, B.I.; Dikhtyar, Y.Y.; Spassky, D.A.; Fedyunin, F.D.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Pavlova, E.T.; Morozov, V.A.; Deyneko, D.V. Synthesis and photoluminescence properties of Ba3(PO4)2:Eu3+/2+ phosphors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 176, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Liu, A.; Xue, W.; Song, Y. High-pressure Raman spectroscopic studies on orthophosphates Ba3(PO4)2 and Sr3(PO4)2. Solid State Com. 2011, 151, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Pakhomovskii, Y.A.; Bogdanova, A.N.; Skiba, V.I. Strontiowhitlockite, Sr9Mg(PO3OH)(PO4)6, a new mineral species from the Kovdor Deposit, Kola Peninsula, U.S.S.R. Can. Mineral. 1991, 29, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sarver, J.F.; Hoffman, M.V.; Hummel, F.A. Phase Equilibria and Tin-Activated Luminescence in Strontium Orthophosphate Systems. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1961, 108, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Pokholok, K.V.; Terekhina, T.P.; Leonidov, I.A.; Mitberg, E.B.; Karelina, V.V.; Kellerman, D.G. Synthesis and Characterization of New Strontium Iron(II) Phosphates, SrFe2(PO4)2 and Sr9Fe1.5(PO4)7. J. Solid State Chem. 2001, 162, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Chen, D. Synthesis of (Sr0.85Zn0.15)3(PO4)2:Eu3+ by a modified solid-state reaction and its luminescent properties for ultraviolet light emitting diodes. Powder Technol. 2009, 194, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Jiao, H. Luminescence properties of (Sr0.86Mg0.14)3(PO4)2:Eu2+,Mn2+ phosphors for LEDs application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 8895–8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, R.; Peng, X.; Cui, R.; Deng, C. Multiple applications of Sr8ZnIn(1-m)Lum(PO4)7:Eu2+/Mn2+ through thermal stability adjustment, spectral tuning, and resonance energy transfer. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1034, 181312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, L.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Cui, R.; Deng, C. A novel single phase multifunctional Sr8ZnIn0.6Sc0.4(PO4)7: Eu2+/Mn2+ phosphor with good thermal stability for optical thermometers, fingerprint detection and WLEDs applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 53232–53245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, I.V.; Zhukovskaya, E.S.; Aksenov, S.M.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Pankrushina, E.A.; Deyneko, D.V. Structural Refinement and Optical Properties of Strontiowhitlockite-Based Mixed Phosphate-Vanadates. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 13669–13683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frondel, C. Whitlockite: A new calcium phosphate, Ca3(PO4)2. Am. Mineral. 1941, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, A.L.; Sinha, D.P. The piezo-electric activity of whitlockite β-Ca3(PO4)2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1967, 28, 1337–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Lebedev, V.N.; Aksenov, S.M.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Pankratov, V.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Gosteva, A.N.; Barbaro, K.; Rau, J.V. Zn2+, Sr2+, and Sm3+ tri-doped whitlockites: Luminescent materials with improved bioactive and antibacterial properties. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 21117–21134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, R.; Calvo, C.; Ito, J.; Sabine, W.K. Crystal Structure of Synthetic Mg-Whitlockite, Ca18Mg2H2(PO4)14. Can. J. Chem. 1974, 52, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, A.; Benhamou, R.A.; Wallez, G.; Lecointre, A.; Viana, B. Site occupancy and mechanisms of thermally stimulated luminescence in Ca9Ln(PO4)7 (Ln=lanthanide). Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 6641–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Izumi, F.; Ikeda, T.; Okui, M.; Malakho, A.P.; Morozov, V.A.; Lazoryak, B.I. Whitlockite-Related Phosphates Sr9A(PO4)7 (A=Sc, Cr, Fe, Ga, and In): Structure Refinement of Sr9In(PO4)7 with Synchrotron X-Ray Powder Diffraction Data. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 168, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimova, E.S.; Pustovarov, V.A.; Shi, Q. Fast 5d-4f luminescence in Sr9RE(PO4)7 (RE = Sc, Lu) complex phosphates doped with Pr3+ ions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2174, 020178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Z.; Xia, D. New whitlockite-type structure material Sr9Y(PO4)7 and its Eu2+ doped green emission properties under NUV light. J. Lumin. 2020, 221, 117114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Seo, Y.W.; Park, S.H.; Choi, B.C.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, J.H. Theoretical design and characterization of high efficient Sr9Ln(PO4)7: Eu2+ phosphors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 127, 110856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, I.V.; Titkov, V.V.; Aksenov, S.M.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Deineko, D.V. Structural Features of Strontiowhitlockite-Based Luminophores. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 65, 1668–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Huang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Molokeev, M.S.; Jiang, X.; Lin, Z.; Atuchin, V.V. Comparative investigations of the crystal structure and photoluminescence property of eulytite-type Ba3Eu(PO4)3 and Sr3Eu(PO4)3. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 7679–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matraszek, A. Study of phase relationships in the Sr3(PO4)2–CePO4 system. Phase diagram and thermal characteristics of phases. J. Solid State Chem. 2013, 203, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Spassky, D.A.; Antropov, A.V.; Ril’, A.I.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Pavlova, E.T.; Lazoryak, B.I. Anomalous oxidation state of europium in the Sr3(PO4)2-type phosphors doped with alkaline cations. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 165, 112296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M.; Sakai, A.; Kamiyama, T.; Hoshikawa, A. Crystal structure analysis of β-tricalcium phosphate Ca3(PO4)2 by neutron powder diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 175, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemon, A.; Courbion, G. The crystal structure of α-SrZn2(PO4)2: A hurlbutite type. J. Solid State Chem. 1990, 85, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chang, C. Effects of Bi3+ co-doping on structure and luminescence of SrZn2(PO4)2-based phosphor. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 10072–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrícek, V.; Dusek, M.; Palatinus, L. Crystallographic Computing System JANA2006: General features. Z. Kristallogr. 2014, 229, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Izumi, F.; Ikeda, T.; Morozov, V.A.; Dilanian, R.A.; Torii, S.; Kopnin, E.M.; Lebedev, O.I.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Lazoryak, B.I. Positional and Orientational Disorder in a Solid Solution of Sr9+xNi1.5-x(PO4)7 (x = 0.3). Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1399–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V. Structural complexity and configurational entropy of crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2016, 72, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaussler, C.; Kieslich, G. crystIT: Complexity and configurational entropy of crystal structures via information theory. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivovichev, S.V. Which Inorganic Structures are the Most Complex? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Krivovichev, V.G.; Hazen, R.M.; Aksenov, S.M.; Avdontceva, M.S.; Banaru, A.M.; Gorelova, L.A.; Ismagilova, R.M.; Kornyakov, I.V.; Kuporev, I.V.; et al. Structural and chemical complexity of minerals: An update. Mineral. Mag. 2022, 86, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aza, P.N.; Santos, C.; Pazo, A.; de Aza, S.; Cuscó, R.; Artús, L. Vibrational Properties of Calcium Phosphate Compounds. 1. Raman Spectrum of β-Tricalcium Phosphate. Chem. Mater. 1997, 9, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneyulu, U.; Pattanayak, D.K.; Vijayalakshmi, U. Snail Shell Derived Natural Hydroxyapatite: Effects on NIH-3T3 Cells for Orthopedic Applications. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophie, Q.; Charlotte, M.; Renate, G.; Julien, H.; Philippe, D.; Georg, B.; Jean Michel, B. Raman and Infrared Studies of Substituted β-TCP. Eng. Mater. 2011, 493–494, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, E.; Balan, E.; Petit, S.; Juillot, F. Vibrational spectroscopic study of three Mg–Ni mineral series in white and greenish clay infillings of the New Caledonian Ni-silicate ores. Eur. J. Mineral. 2021, 33, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Hussain, Z.; Rehman, M.R.; Idrees, M.U. Effect of strontium and iron on the structural integrity and drug delivery of Whitlockite. Open Ceram. 2023, 14, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Dai, S.; Chen, X.; Qiu, K. Synthesis and photoluminescence properties of Sr3(PO4)2:Re3+, Li+ (Re = Eu, Sm) red phosphors for white light-emitting diodes. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 11244–11249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, I.V.; Yashina, K.N.; Zhukovskaya, E.S.; Gutnikov, S.I.; Aksenov, S.M.; Deyneko, D.V. Phase Formation in the System of Triple Phosphates Sr–M2+–Ln3+ (M2+ = Zn2+, Mg2+, Mn2+; Ln3+ = Eu3+, Tb3+). Crystallogr. Rep. 2025, 70, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, R.A.; Bessière, A.; Wallez, G.; Viana, B.; Elaatmani, M.; Daoud, M.; Zegzouti, A. New insight in the structure–luminescence relationships of Ca9Eu(PO4)7. J. Solid State Chem. 2009, 182, 2319–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikhtyar, Y.Y.; Spassky, D.A.; Morozov, V.A.; Deyneko, D.V.; Belik, A.A.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Lazoryak, B.I. Site occupancy, luminescence and dielectric properties of β-Ca3(PO4)2-type Ca8ZnLn(PO4)7 host materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908, 164521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Spassky, D.A.; Morozov, V.A.; Aksenov, S.M.; Kubrin, S.P.; Molokeev, M.S.; Lazoryak, B.I. Role of the Eu3+ Distribution on the Properties of β-Ca3(PO4)2 Phosphors: Structural, Luminescent, and 151Eu Mössbauer Spectroscopy Study of Ca9.5–1.5xMgEux(PO4)7. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 3961–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Ma, B. Color tunable Dy3+-doped Sr9Ga(PO4)7 phosphors for optical thermometric sensing materials. Opt. Mater. 2020, 107, 110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Shi, Q.; You, F.; Ivanovskikh, K.V.; Leonidov, I.I.; Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cui, C.e. Site occupancy and luminescence of Ce3+ ions in whitlockite-related strontium lutetium phosphate. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 116, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, I.V.; Spassky, D.A.; Krutyak, N.R.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Zhukovskaya, E.S.; Aksenov, S.M.; Deyneko, D.V. Co-Doping Effect of Mn2+ and Eu3+ on Luminescence in Strontiowhitlockite Phosphors. Molecules 2024, 29, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, W.; Jiao, M.; Sun, W.; Fu, C.; Chen, X.; Luan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H. Long-lasting ultraviolet-A persistent luminescence in Sr9Mg1.5(PO4)7:Ce3+,A+ (A+ = Li+, Na+, K+) phosphors by X-rays rapid charging. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2026, 346, 126853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, B.; Yu, J. Tunable emission in Sr9LiY0.667(PO4)7: Eu2+, Mn2+ phosphor via energy transfer for pc-LEDs application. Opt. Mater. 2025, 162, 116850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, P.A. Some misconceptions concerning the electronic spectra of tri-positive europium and cerium. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5090–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Xue, H. Preparation of Sr8Mg1−mZnmY(PO4)7:Eu2+ solid solutions and their luminescence properties. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 62230–62236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, C.; Ding, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Q. Regulating photoluminescence behavior by neighboring-cation-size in Sr8CaX(PO4)7: Eu2+ (X = Al and Ga) phosphors for high color rendering solid-state lighting source. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, Y. Novel orange light emitting phosphor Sr9(Li, Na, K)Mg(PO4)7: Eu2+ excited by NUV light for white LEDs. Acta Mater. 2016, 120, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszka, K.; Nowak, N.; Kowalski, R.M.; Zukrowski, J.; Wiglusz, R.J. Anomalous luminescence properties and cytotoxicity assessment of Sr3(PO4)2 co-doped with Eu2+/3+ ions for luminescence temperature sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 9092–9105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K. DIAMOND (version 4.6.8); Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blatov, V.A.; Shevchenko, A.P.; Proserpio, D.M. Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3576–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Sr9Zn1.5(PO4)7 |

|---|---|

| SG | Rm |

| Lattice parameters: a, Å | 10.595(3) |

| c, Å | 19.738(6) |

| Unit cell volume, Å3 | 1918.9(1) |

| Calculated density, g/cm3 | 4.0277 |

| Data collection | |

| Diffractometer | RIGAKU Ultima III |

| Radiation/Wavelength (k, Å) | CuKα1+α2/1.54186 Å |

| 2θ range (o) | 5–65 |

| Step scan (2θ) | 0.02 |

| Refinement | |

| Background function | 15 Legendre polynoms |

| R and Rw for Bragg reflections, % | 9.01/10.42 |

| RP, RwP, Rexp, % | 7.57/11.23/4.37 |

| Goodness of fit (ChiQ) | 2.58 |

| Max./min. residual density, e/Å3 | 1.68/−1.48 |

| CSD number | 2,494,889 |

| Atom | Occupation, ai | x | y | z | Uiso∙100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sr1a | 0.87(1) | 0.1885(4) | −0.1885(4) | 0.5362(2) | 0.14 |

| Sr1b | 0.13(1) | 0.235(3) | −0.235(3) | 0.5504(15) | 0.14 |

| Sr3a | 0.401(3) | −0.5208(6) | 0.5208(6) | 0.0093(5) | 0.49 |

| Sr3b | 0.099(3) | 0.389(1) | 0.611(1) | −0.017(2) | 0.49 |

| Zn4 | 0.0833 | 0.174(6) | 0.087(3) | 0.388(3) | 3 |

| Zn5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3(4) |

| P1 | 1 | −2/3 | 2/3 | 1/6 | 0.01 |

| P2 | 1 | 0.4886(6) | −0.4886(6) | 0.3979(8) | 2.8(4) |

| O11 | 1 | −0.542(2) | 0.811(2) | 0.138(1) | 0.1 |

| O21a | 0.62(5) | 0.463(2) | −0.463(2) | 0.319(1) | 0.1 |

| O21b | 0.38(5) | 0.454(6) | −0.561(7) | 0.323(2) | 0.1 |

| O22 | 0.87(1) | 0.5758(8) | −0.5758(8) | 0.407(1) | 0.1 |

| O24a | 0.13(1) | 0.455(6) | −0.455(6) | 0.471(3) | 0.1 |

| O24b | 0.87(1) | 0.1885(4) | −0.1885(4) | 0.5362(2) | 0.1 |

| Bonds | Distance, Ắ | Bonds | Distance, Ắ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sr1a | O21b | 2.45(4) | Sr3b | O21a × 2 | 2.16(3) |

| O22 | 2.41(1) | O22 × 2 | 2.58(3) | ||

| O11 | 2.48(3) | O21b × 2 | 2.76(9) | ||

| O11 | 2.55(3) | Zn4 | O11 | 1.91(6) | |

| O21a | 2.53(2) | O11 | 1.91(6) | ||

| O24a | 2.58(1) | O21b | 1.91(9) | ||

| O24a | 2.58(1) | O21b | 1.91(9) | ||

| O24b | 2.79(6) | O11 | 2.60(5) | ||

| Sr3a | O22 | 2.46(1) | O11 | 2.60(7) | |

| O22 | 2.57(1) | O11 | 2.84(6) | ||

| O22 | 2.57(1) | O11 | 2.84(6) | ||

| O21b | 2.55(5) | Zn5 | O24a × 6 | 2.21(2) | |

| O11 | 2.93(3) | P1 | O11 × 4 | 1.54(3) | |

| O11 | 2.93(3) | P2 | O24a | 1.61(1) | |

| O21b | 2.85(5) | O21b | 1.62(5) | ||

| O21b | 2.85(5) | O22 × 2 | 1.70(1) |

| Sample | Ref. | Complexity, bit/atom | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imix | |||||

| Ca9Zn1.5(PO4)7 | 4.076 | 4.098 | 0.022 | 4.054 | |

| Sr9Zn1.5(PO4)7 | This work | 3.267 | 4.203 | 0.936 | 2.331 |

| Sr9.3Ni1.2(PO4)7 | 3.016 | 3.887 | 0.871 | 2.145 | |

| Sr8ZnEu(PO4)7 | 3.016 | 3.445 | 0.429 | 2.588 | |

| Doped R3+ Ion | Radius, Å/CN | Dr, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sr2+ 1.26 Å/8 | Sr2+ 1.18 Å/6 | Ca2+ 1.12 Å/8 | Ca2+ 1.00 Å/6 | Zn2+ 0.74 Å/6 | ||

| Ga3+ [58] | 0.62 Å/6 | – | 47.5 | – | 38 | 16.2 |

| Lu3+ [59] | 0.98 Å/8 | 22.2 | – | 12.5 | ||

| 0.86 Å/6 | – | 27.1 | – | 14 | 16.2 | |

| Y3+ [33] | 1.02 Å/8 | 19 | – | 8.9 | ||

| 0.90 Å/6 | – | 23.7 | – | 10 | 21.6 | |

| Eu3+ This work | 1.07 Å/8 | 15.1 | – | 4.5 | – | |

| 0.95 Å/6 | – | 19.5 | – | 5.0 | 28 | |

| Sr9–1.5xZn1.5Eux(PO4)7 | ||||

| x | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| R/O | 3.68 | 3.52 | 3.72 | 3.44 |

| CIE (X;Y) | 0.653; 0.351 | 0.649; 0.348 | 0.653; 0.349 | 0.649; 0.350 |

| Sr9.5–1.5xZnEux(PO4)7 | ||||

| x | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| R/O | 3.65 | 3.51 | 3.58 | 3.63 |

| CIE (X;Y) | 0.650; 0.349 | 0.652; 0.348 | 0.651; 0.349 | 0.650; 0.349 |

| Sr3(PO4)2:Eu3+ | SrZn2(PO4)2:Eu3+ | Sr3La(PO4)3:Eu3+ | (Sr0.85Zn0.15)3(PO4)2:Eu3+ | |

| crystallographic site symmetry | C1 + C3v | C4v | C3 | C1 |

| R/O | 1.75 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 3.8 |

| CIE (X;Y) | 0.632; 0.366 | 0.623; 0.376 | 0.638; 0.361 | 0.651; 0.348 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Deyneko, D.V.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Titkov, V.V.; Latipov, E.V.; Kireev, V.E.; Banaru, D.A.; Aksenov, S.M.; Lazoryak, B.I. Unveiling the Phase Formations in the Sr–Zn–Eu3+ Orthophosphate System: Crystallographic Analysis and Photoluminescent Properties. Inorganics 2026, 14, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010015

Deyneko DV, Nikiforov IV, Titkov VV, Latipov EV, Kireev VE, Banaru DA, Aksenov SM, Lazoryak BI. Unveiling the Phase Formations in the Sr–Zn–Eu3+ Orthophosphate System: Crystallographic Analysis and Photoluminescent Properties. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeyneko, Dina V., Ivan V. Nikiforov, Vladimir V. Titkov, Egor V. Latipov, Vadim E. Kireev, Darya A. Banaru, Sergey M. Aksenov, and Bogdan I. Lazoryak. 2026. "Unveiling the Phase Formations in the Sr–Zn–Eu3+ Orthophosphate System: Crystallographic Analysis and Photoluminescent Properties" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010015

APA StyleDeyneko, D. V., Nikiforov, I. V., Titkov, V. V., Latipov, E. V., Kireev, V. E., Banaru, D. A., Aksenov, S. M., & Lazoryak, B. I. (2026). Unveiling the Phase Formations in the Sr–Zn–Eu3+ Orthophosphate System: Crystallographic Analysis and Photoluminescent Properties. Inorganics, 14(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010015