Divalent Europium Complexes with Phenochalcogenato Ligands: Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescence Properties

Abstract

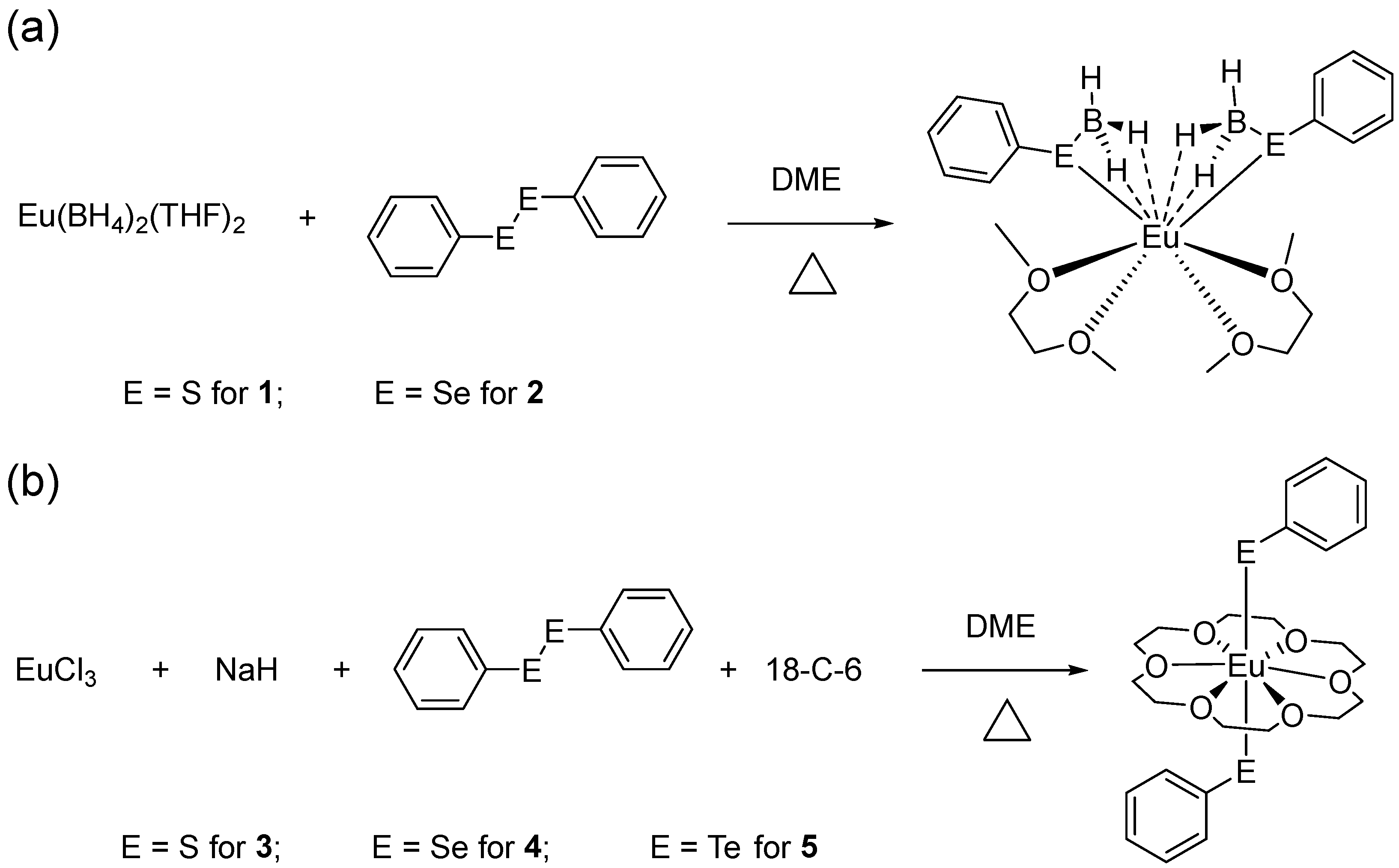

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis

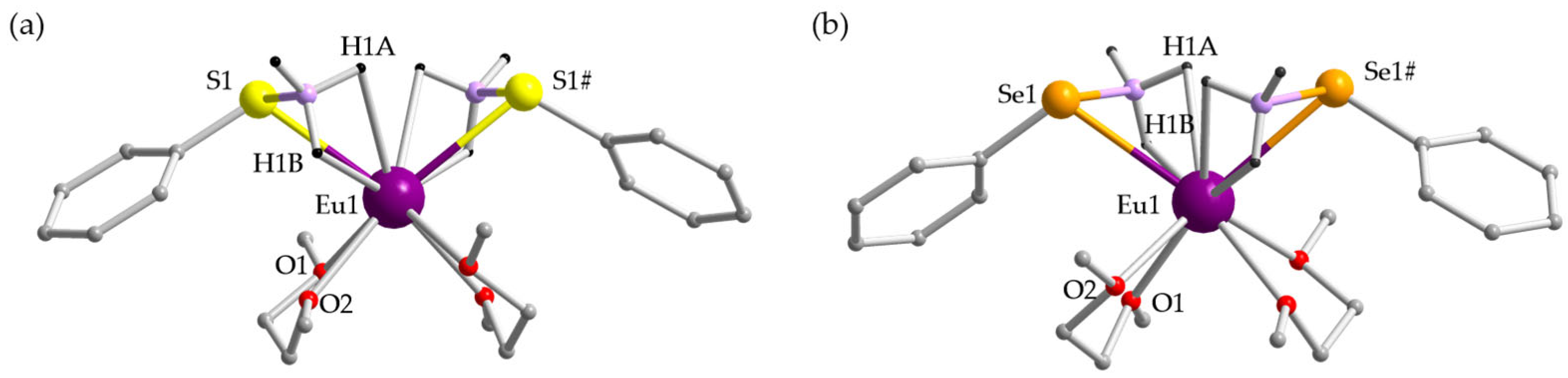

2.2. Crystal Structures

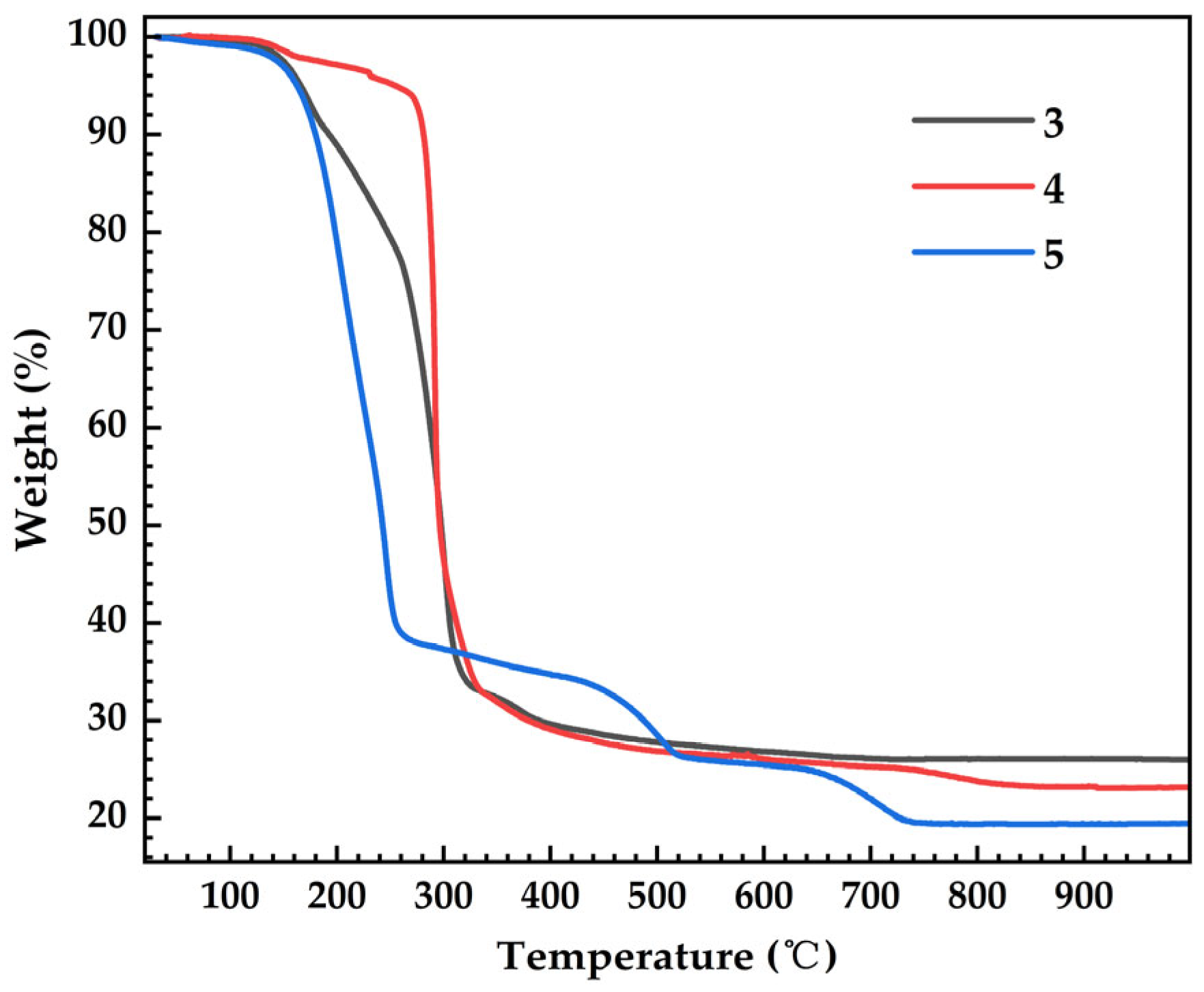

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

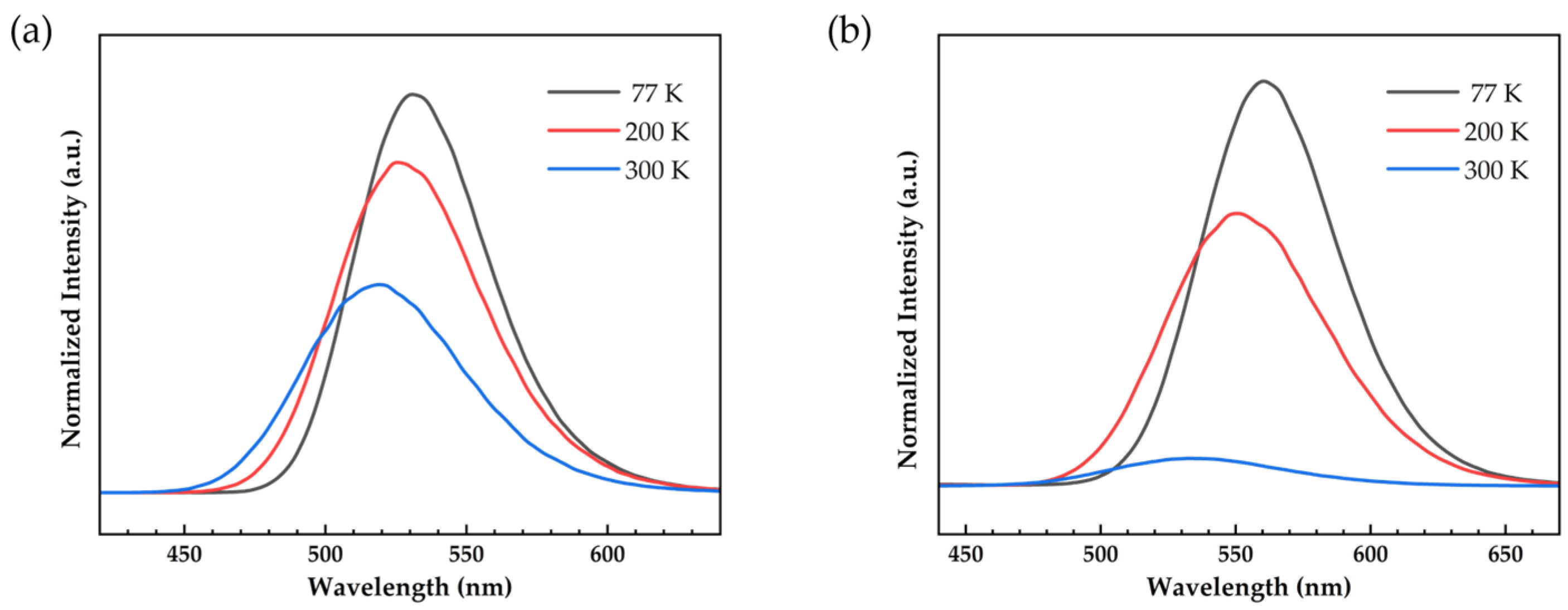

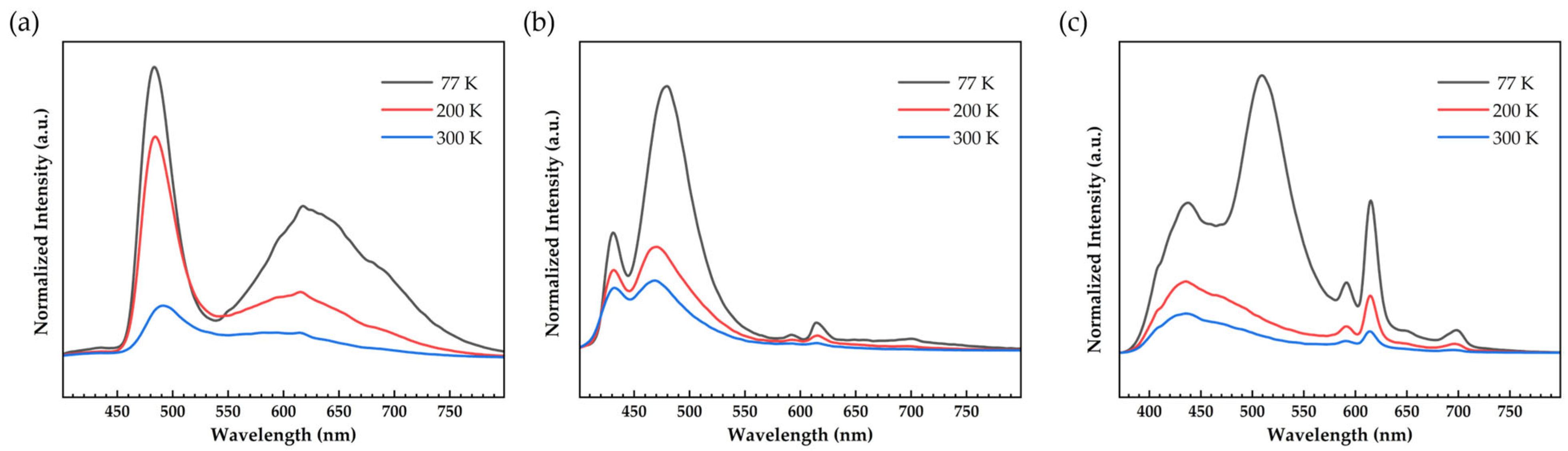

2.4. Photophysical Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Considerations

3.2. Synthesis of Complexes 1–5

3.3. Crystal Structure Determination

3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.5. Photophysical Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C. Rare Earth Coordination Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W. Chemistry of Non-Traditional Oxidation States of Rare Earth Metals. Sci. Sin. Chim. 2020, 50, 1504–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedal, J.C.; Evans, W.J. A Rare-Earth Metal Retrospective to Stimulate All Fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18354–18367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.-W.; Hu, H.-S.; Schwarz, W.H.E.; Li, J. Physical Origin and Periodicity of the Highest Oxidation States in Heavy-Element Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Yang, Q.-S.; Zheng, Z. Pentavalent Praseodymium Complexes Culminated in the Pursuit of High-valence Lanthanide Compounds. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2025, 44, 100696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.R.; Bates, J.E.; Ziller, J.W.; Furche, F.; Evans, W.J. Completing the Series of +2 Ions for the Lanthanide Elements: Synthesis of Molecular Complexes of Pr2+, Gd2+, Tb2+, and Lu2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9857–9868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Gong, J.; Li, W.; Mo, Z.; Shen, J. Giant Low-Field Cryogenic Magnetocaloric Effect in a Polycrystalline EuB4O7 Compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 3315–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Hu, F.; Wang, J.-T.; Xiang, J.; Sun, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, T.; Mo, Z.; et al. A Record-High Cryogenic Magnetocaloric Effect Discovered in EuCl2 Compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 35016–35022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Jiang, J.; Tian, L.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; et al. Ferromagnetic Eu2SiO4 Compound with a Record Low-Field Magnetocaloric Effect and Excellent Thermal Conductivity Near Liquid Helium Temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 14684–14693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Manvell, A.S.; Kubus, M.; Dunstan, M.A.; Lorusso, G.; Gracia, D.; Jørgensen, M.S.B.; Kegnæs, S.; Wilhelm, F.; Rogalev, A.; et al. Towards Frustration in Eu(II) Archimedean tessellations. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1609–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvell, A.S.; Dunstan, M.A.; Gracia, D.; Hrubý, J.; Kubus, M.; McPherson, J.N.; Palacios, E.; Weihe, H.; Hill, S.; Schnack, J.; et al. A Triangular Frustrated Eu(II)–Organic Framework for Sub-Kelvin Magnetic Refrigeration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 7597–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errulat, D.; Harriman, K.L.M.; Gálico, D.A.; Salerno, E.V.; van Tol, J.; Mansikkamäki, A.; Rouzières, M.; Hill, S.; Clérac, R.; Murugesu, M. Slow Magnetic Relaxation in a Europium(II) Complex. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Bian, Z. Rare Earth Complexes with 5d–4f Transition: New Emitters in Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhan, C. Recent Advances in d-f Transition Lanthanide Complexes for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes: Insights Into Structure–Luminescence Relationships. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2402198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ganesan, P.; Gao, P. Harnessing d-f transition rare earth complexes for single layer white organic light emitting diodes. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 43, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Xia, Z. Hybrid Eu(II)-Bromide Scintillators with Efficient 5d-4f Bandgap Transition for X-ray Imaging. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Han, K.; Zhang, S.; Xia, Z. Organic Cation Methylation Design of Hybrid Eu(II)-based Halide Scintillators for Improved X-Ray Detection and Imaging. Adv. Mater. 2025, e10379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Han, K.; Xia, Z. Suppressed Concentration Quenching via Divalent Eu/Sr Alloying in Hybrid Iodides Scintillators Toward Bright Luminescence for X-ray Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202514331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.; Heck, J.G.; Habicht, M.H.; Oña-Burgos, P.; Feldmann, C.; Roesky, P.W. [Ln(BH4)2(THF)2] (Ln = Eu, Yb)—A Highly Luminescent Material. Synthesis, Properties, Reactivity, and NMR Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16983–16986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhan, G.; Liu, H.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Z. Highly Efficient and Air-Stable Eu(II)-Containing Azacryptates Ready for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, T.; Cai, Z.; Qi, H.; Guo, R.; Huo, P.; Liu, Z.; Bian, Z. Systematic Tuning of the Emission Colors and Redox Potential of Eu(II)-Containing Cryptates by Changing the N/O Ratio of Cryptands. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4794–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Huo, P.; Yu, G.; Guo, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, W.; Wang, L.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Z. Europium(II) Complexes with Substituted Tris(2-aminoethyl)amine/Triethanolamine Ligand and their Application in Blue Spin-Coated Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2200952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, M.A.; Gable, R.W.; Boskovic, C. Modulating the Electronic Properties of Divalent Lanthanoid Complexes with Subtle Ligand Tuning. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 3315–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Huo, P.; Guo, R.; Yu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, K.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Z. Fine Tuning the Steric Hindrance of the Eu(II) Tris(pyrazolyl)borate Complex for a Blue Organic Light-Emitting Diode. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 9834–9840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Huo, P.; Zheng, N.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.; Fang, P.; Zhou, X.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Z. Europium(II) Complex with d-f Transition: New Emitter for Blue Light-Emitting Electrochemical Cells with an External Quantum Efficiency of 19.8%. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2419849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, M.A.; Leicht, S.; Feldmann, C. Crown-Ether Coordination Compounds of Europium and 24-Crown-8. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jin, J.; Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z. Rational Design and Synthesis of Narrow-Band Emitting Eu(II)-Based Hybrid Halides via Alkyl Thermal Cleavage. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, R.M.; Gálico, D.A.; Chartrand, D.; Suturina, E.A.; Murugesu, M. Toward Opto-Structural Correlation to Investigate Luminescence Thermometry in an Organometallic Eu(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, R.M.; Gálico, D.A.; Chartrand, D.; Murugesu, M. Ligand Effects on the Emission Characteristics of Molecular Eu(II) Luminescence Thermometers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 34118–34129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Rodriguez, R.M.; Gálico, D.A.; Murugesu, M. Exploring a New Family of (Phosphinochalcogenoyl)Europocenes for Magneto-Optical Thermometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202517812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, R.; Qi, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Niu, H.; Jiang, H.; Bian, Z.; Liu, Z. Heavy-Atom-Induced Narrow Emission in Chalcogen-Coordinating Lanthanide Cerium(III) Complexes. Aggregate 2025, 6, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashima, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Fukumoto, H.; Kanehisa, N.; Kai, Y.; Nakamura, A. Formation of Lanthanoid(II) and Lanthanoid(III) Thiolate Complexes Derived from Metals and Organic Disulfides: Crystal Structures of [{Ln(SAr)(μ-SAr)(thf)3}2](Ln = Sm, Eu), [Sm(SAr)3(py)2(thf)] and [Yb(SAr)3(py)3](Ar = 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl; py = pyridine). J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 2523–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.; Lee, J.; Brennan, J.G. Heterometallic Eu/M(II) Benzenethiolates (M = Zn, Cd, Hg): Synthesis, Structure, and Thermolysis Chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 5919–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardini, M.; Brennan, J. Europium Pyridinethiolates: Synthesis, Structure, and Thermolysis. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 6179–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melman, J.H.; Emge, T.J.; Brennan, J.G. Fluorinated Thiolates of Divalent and Trivalent Lanthanides. Ln−F Bonds and the Synthesis of LnF3. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 1078–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelkort, J.; van Smaalen, S.; Hauber, S.O.; Niemeyer, M. Phase Transition and Crystal Structure of the Monomeric Europium(II) Thiolate Eu(SC36H49)2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2007, 633, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.M.; Deacon, G.B.; Forsyth, C.M.; Junk, P.C.; Wiecko, M. A Structural Investigation of Trivalent and Divalent Rare Earth Thiocyanate Complexes Synthesised by Redox Transmetallation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 2813–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.-P.; Chan, Y.-C.; Mak, T.C.W. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Thiophosphinoyl Late-Transition-Metal and Divalent Lanthanide Complexes Derived from 2-Quinolyl-Linked (Thiophosphorano)methane. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 6103–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, M.E.; Pushkarev, A.P.; Fukin, G.K.; Rumyantsev, R.V.; Konev, A.N.; Bochkarev, M.N. Synthesis of EuS and EuSe Particles via Thermal Decomposition of Dithio- and Diselenophosphinate Europium Complexes. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2017, 12, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silantyeva, L.I.; Ilichev, V.A.; Shavyrin, A.S.; Yablonskiy, A.N.; Rumyantcev, R.V.; Fukin, G.K.; Bochkarev, M.N. Unexpected Findings in a Simple Metathesis Reaction of Europium and Ytterbium Diiodides with Perfluorinated Mercaptobenzothiazolates of Alkali Metals. Organometallics 2020, 39, 2972–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, O.C., Jr.; Marwitz, A.C.; Swanson, J.; Bertke, J.A.; Hartman, T.; Monteiro, J.H.S.K.; de Bettencourt-Dias, A.; Knope, K.E.; Stoll, S.L. Lanthanide Luminescence and Thermochromic Emission from Soft-Atom Donor Dichalcogenoimidodiphosphinate Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 15547–15557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokouende, S.S.; Ward, C.L.; Allen, M.J. Understanding the Coordination Chemistry and Structural and Photophysical Properties of EuII- and SmII-Containing Complexes of Hexamethylhexacyclen and Noncyclic Tetradentate Amines. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 16991–17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrosablin, A.N.; Ilichev, V.A.; Rogozhin, A.F.; Kuznetsova, O.V.; Dorovatovskii, P.V.; Rumyantcev, R.V.; Fukin, G.K.; Bochkarev, M.N. Synthesis and Structures of Eu(II) Complexes with Anionic Perfluoro-2-mercaptobenzothiazolate and Macrocyclic Ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2026, 590, 122987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardini, M.; Emge, T.; Brennan, J.G. One-dimensional Coordination Polymers: [{(pyridine)2Eu(μ-SeC6H5)2}4]n and [(THF)3Eu(μ-SeC6H5)2]n. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8501–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardini, M.; Emge, T.; Breenan, J.G. Heterometallic Rare Earth/Group II Metal Chalcogenolate Clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 6941–6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardini, M.; Emge, T.J.; Brennan, J.G. Lanthanide-Group 12 Metal Chalcogenolates: A Versatile Class of Compounds. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 5327–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Emge, T.J.; Brennan, J.G. Heterometallic Lanthanide−Group 14 Metal Chalcogenolates. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 5064–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C.A.P.; Schlimgen, A.W.; Albrecht-Schönzart, T.E.; Batista, E.R.; Gaunt, A.J.; Janicke, M.T.; Kozimor, S.A.; Scott, B.L.; Stevens, L.M.; White, F.D.; et al. Structural and Spectroscopic Comparison of Soft-Se vs. Hard-O Donor Bonding in Trivalent Americium/Neodymium Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9459–9466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cary, D.R.; Arnold, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Divalent Lanthanide Selenolates and Tellurolates. X-ray Crystal Structures of Yb[SeSi(SiMe3)3]2(TMEDA)2 and {Eu[TeSi(SiMe3)3]2(DMPE)2}2μ-DMPE). Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasnis, D.V.; Brewer, M.; Lee, J.; Emge, T.J.; Brennan, J.G. Rare Earth Phenyltellurolates: 1D Coordination Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 7129–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, G.; Santner, S.; Donsbach, C.; Assmann, M.; Müller, M.; Dehnen, S. Solvothermal and Ionothermal Syntheses and Structures of Amine- and/or (Poly-)Chalcogenide Coordinated Metal Complexes. Z. Krist.-Cryst. Mater. 2014, 229, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, R.; Dey, S.; Guo, Z.; Butcher, R.J.; Junk, P.C.; Turner, D.R.; Singh, H.B.; Deacon, G.B. Pushing the Boundary of Covalency in Lanthanoid-Tellurium Bonds: Insights from the Synthesis, Molecular and Electronic Structures of Low-Coordinate, Monomeric Europium(II) and Ytterbium(II) Tellurolates. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Jiang, X.-L.; Li, L.; Xu, C.-Q.; Li, J.; Zheng, Z. Atomically Precise Semiconductor Clusters of Rare-earth Tellurides. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Z. Lanthanide-Based Molecular Magnetic Semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xue, T.-J.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Z. Rare-earth Chalcogenidotetrachloride Clusters (RE3ECl4, RE = Dy, Gd, Y; E = S, Se, Te): Syntheses and Materials Properties. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 16506–16514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-Q.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Z. Triply Chalcogenophenolato-Bridged Erbium-Cyclooctatetraenyl Complexes: Syntheses and Single-Molecule Magnetic Properties. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 8560–8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Efficient Reduction Method Enables Access to Rare-earth Telluride Clusters. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réant, B.L.L.; Seed, J.A.; Whitehead, G.F.S.; Goodwin, C.A.P. Uranium(III) and Uranium(IV) meta-Terphenylthiolate Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 3161–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starynowicz, P.; Bukietyńska, K.; Gołąb, S.; Ryba-Romanowski, W.; Sokolnicki, J. Europium(II) Complexes With Benzo-18-Crown-6. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2002, 2344–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starynowicz, P. Europium(II) Complexes with Unsubstituted Crown Ethers. Polyhedron 2003, 22, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyakova, E.; Wolf, S.; Lebedkin, S.; Bayarjargal, L.; Neumeier, B.L.; Bartenbach, D.; Holzer, C.; Klopper, W.; Winkler, B.; Kappes, M.; et al. 18-Crown-6 Coordinated Metal Halides with Bright Luminescence and Nonlinear Optical Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, T.N.; Molinari, S.; Justiniano, S.; McLeod, G.M.; Albrecht-Schönzart, T.E. Structural and Spectroscopic Analysis of Ln(II) 18-crown-6 and Benzo-18-crown-6 Complexes (Ln = Sm, Eu, Yb). Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.; Brookfield, A.; Whitehead, G.F.S.; Natrajan, L.S.; McInnes, E.J.L.; Oakley, M.S.; Mills, D.P. Isolation and Electronic Structures of Lanthanide(II) Bis(trimethylsilyl)phosphide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 18120–18136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, P.; Atsumi, M. Molecular Single-Bond Covalent Radii for Elements 1–118. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Han, T.; Hu, Y.-Q.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Syntheses, Structures and Magnetic Properties of a Series of Mono- and Di-nuclear Dysprosium(III)-Crown-Ether Complexes: Effects of a Weak Ligand-Field and Flexible Cyclic Coordination Modes. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-S.; Blackmore, W.J.A.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Giansiracusa, M.J.; Reta, D.; Vitorica-Yrezabal, I.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Chilton, N.F.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Studies of the Temperature Dependence of the Structure and Magnetism of a Hexagonal-Bipyramidal Dysprosium(III) Single-Molecule Magnet. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-J.; Luo, Q.-C.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-Z. Bis-Alkoxide Dysprosium(III) Crown Ether Complexes Exhibit Tunable Air Stability and Record Energy Barrier. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2308548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, M.; Brik, M.G.; Spassky, D.; Tsukerblat, B. Crystal Field Splitting of 5d States and Luminescence Mechanism in SrAl2O4:Eu2+ Phosphor. J. Lumin. 2017, 182, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, J.J.; Smet, P.F.; Seijo, L.; Barandiarán, Z. Insights into the Complexity of the Excited States of Eu-doped Luminescent Materials. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Upton, B.M.; Khan, S.I.; Diaconescu, P.L. Synthesis and Characterization of Paramagnetic Lanthanide Benzyl Complexes. Organometallics 2013, 32, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identification Code | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C20H36B2EuO4S2 | C20H36B2EuO4Se2 | C24H34EuO6S2 | C24H34EuO6S2 | C24H34EuO6Te2 |

| Formula weight | 578.19 | 671.99 | 634.59 | 728.39 | 825.67 |

| Temperature/K | 100 | 100 | 100.03 | 100 | 100.00 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | C2/c | C2/c | P21/c | Pna21 | Pna21 |

| a/Å | 23.5147(7) | 23.6819(9) | 10.2493(3) | 25.6348(7) | 26.0466(7) |

| b/Å | 8.2207(3) | 8.3484(3) | 17.0490(6) | 8.7538(2) | 8.8152(2) |

| c/Å | 17.0919(9) | 17.1792(7) | 7.9684(2) | 11.7448(3) | 12.1672(3) |

| α/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β/° | 130.4380(10) | 130.3130(10) | 112.0540(10) | 90 | 90 |

| γ/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 2514.69(18) | 2589.85(17) | 1290.52(7) | 2635.56(12) | 2793.66(12) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 5.45 to 55.01 | 5.43 to 54.98 | 4.91 to 55.04 | 4.92 to 55.13 | 5.71 to 55.01 |

| Reflections collected | 16,350 | 17,017 | 11,479 | 33,193 | 73,313 |

| Independent reflections | 2877 [Rint = 0.0266, Rsigma = 0.0193] | 2913 [Rint = 0.0330, Rsigma = 0.0231] | 2961 [Rint = 0.0260, Rsigma = 0.0238] | 6039 [Rint = 0.0288, Rsigma = 0.0255] | 6429 [Rint = 0.0449, Rsigma = 0.0248] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2877/0/145 | 2913/0/146 | 2961/0/151 | 6039/1/299 | 6429/1/298 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.083 | 1.126 | 1.045 | 1.045 | 1.094 |

| Final R indexes | R1 = 0.0130 | R1 = 0.0161 | R1 = 0.0159 | R1 = 0.0130 | R1 = 0.0182 |

| [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | wR2 = 0.0330 | wR2 = 0.0388 | wR2 = 0.0369 | wR2 = 0.0286 | wR2 = 0.0416 |

| Final R indexes | R1 = 0.0133 | R1 = 0.0164 | R1 = 0.0185 | R1 = 0.0144 | R1 = 0.0209 |

| [all data] | wR2 = 0.0333 | wR2 = 0.0390 | wR2 = 0.0384 | wR2 = 0.0292 | wR2 = 0.0425 |

| 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu1-S1 | 3.0407(3) | Eu1-Se1 | 3.1445(2) |

| Eu1-O1 | 2.5716(10) | Eu1-O1 | 2.5799(12) |

| Eu1-O2 | 2.5875(10) | Eu1-O2 | 2.5837(12) |

| Eu1-H1A | 2.728(19) | Eu1-H1A | 2.55(2) |

| Eu1-H1B | 2.517(16) | Eu1-H1B | 2.71(2) |

| S1-B1 | 1.9486(16) | Se1-B1 | 2.098(2) |

| S1-Eu1-S1 #1 | 105.224(12) | Se1-Eu1-Se1 #1 | 103.744(7) |

| B1-Eu1-B1 #1 | 98.63(7) | B1-Eu1-B1 #1 | 99.20(8) |

| S1-Eu1-B1 | 38.22(3) | B1-Eu1-Se1 | 40.26(4) |

| O1-Eu1-O2 | 63.74(3) | O1-Eu1-O2 | 63.95(4) |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu1-S1 | 2.9474(4) | Eu1-Se1 | 3.0518(3) | Eu1-Te1 | 3.2585(3) |

| - | - | Eu1-Se2 | 3.1180(3) | Eu1-Te2 | 3.3275(4) |

| Eu1-O1 | 2.7319(11) | Eu1-O1 | 2.7187(18) | Eu1-O1 | 2.695(3) |

| Eu1-O2 | 2.7343(11) | Eu1-O2 | 2.6662(18) | Eu1-O2 | 2.708(3) |

| Eu1-O3 | 2.7062(11) | Eu1-O3 | 2.7224(19) | Eu1-O3 | 2.667(3) |

| - | - | Eu1-O4 | 2.7098(19) | Eu1-O4 | 2.733(3) |

| - | - | Eu1-O5 | 2.7248(18) | Eu1-O5 | 2.711(3) |

| - | - | Eu1-O6 | 2.7092(19) | Eu1-O6 | 2.718(3) |

| Avg. a Eu-O | 2.72 | Avg. Eu-O | 2.71 | Avg. Eu-O | 2.71 |

| S1-Eu1-S1 #1 | 180.0 | Se1-Eu1-Se2 | 170.536(9) | Te1-Eu1-Te2 | 171.536(10) |

| O1-Eu1-O2 | 60.91(3) | O1-Eu1-O2 | 59.33(6) | O1-Eu1-O2 | 60.03(10) |

| O2-Eu1-O3 | 60.28(3) | O2-Eu1-O3 | 61.54(6) | O2-Eu1-O3 | 59.46(10) |

| O3 #1-Eu1-O1 | 59.44(4) | O3-Eu1-O4 | 60.29(6) | O3-Eu1-O4 | 60.84(10) |

| - | - | O4-Eu1-O5 | 59.04(5) | O4-Eu1-O5 | 59.96(10) |

| - | - | O5-Eu1-O6 | 60.80(6) | O5-Eu1-O6 | 59.40(10) |

| - | - | O6-Eu1-O1 | 60.22(6) | O6-Eu1-O1 | 60.99(10) |

| Avg. b O-Eu-O | 60.21 | Avg. O-Eu-O | 60.20 | Avg. O-Eu-O | 60.11 |

| Rng. c S-Eu-O | 79.18(3)–100.82(3) | Rng. Se-Eu-O | 74.92(4)–106.73(4) | Rng. Te-Eu-O | 76.57(7)–102.40(7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Z.-F.; Yang, Q.-S.; Ding, Y.-S.; Zheng, Z. Divalent Europium Complexes with Phenochalcogenato Ligands: Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescence Properties. Inorganics 2025, 13, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120413

Wu Z-F, Yang Q-S, Ding Y-S, Zheng Z. Divalent Europium Complexes with Phenochalcogenato Ligands: Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescence Properties. Inorganics. 2025; 13(12):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120413

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Zhi-Feng, Qing-Song Yang, You-Song Ding, and Zhiping Zheng. 2025. "Divalent Europium Complexes with Phenochalcogenato Ligands: Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescence Properties" Inorganics 13, no. 12: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120413

APA StyleWu, Z.-F., Yang, Q.-S., Ding, Y.-S., & Zheng, Z. (2025). Divalent Europium Complexes with Phenochalcogenato Ligands: Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Luminescence Properties. Inorganics, 13(12), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120413