Contribution of Microwave Irradiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Compounds: An Italian Approach

Abstract

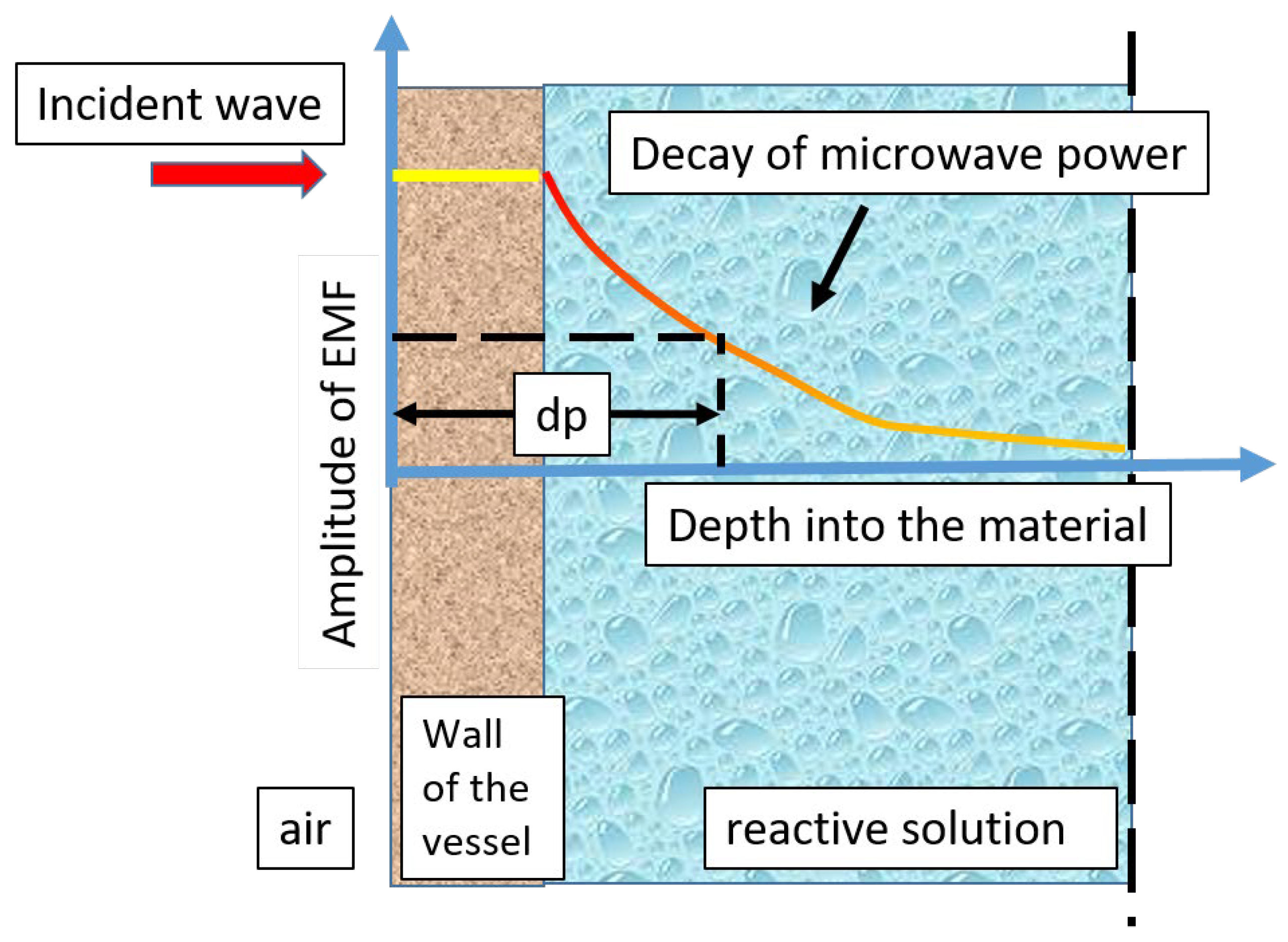

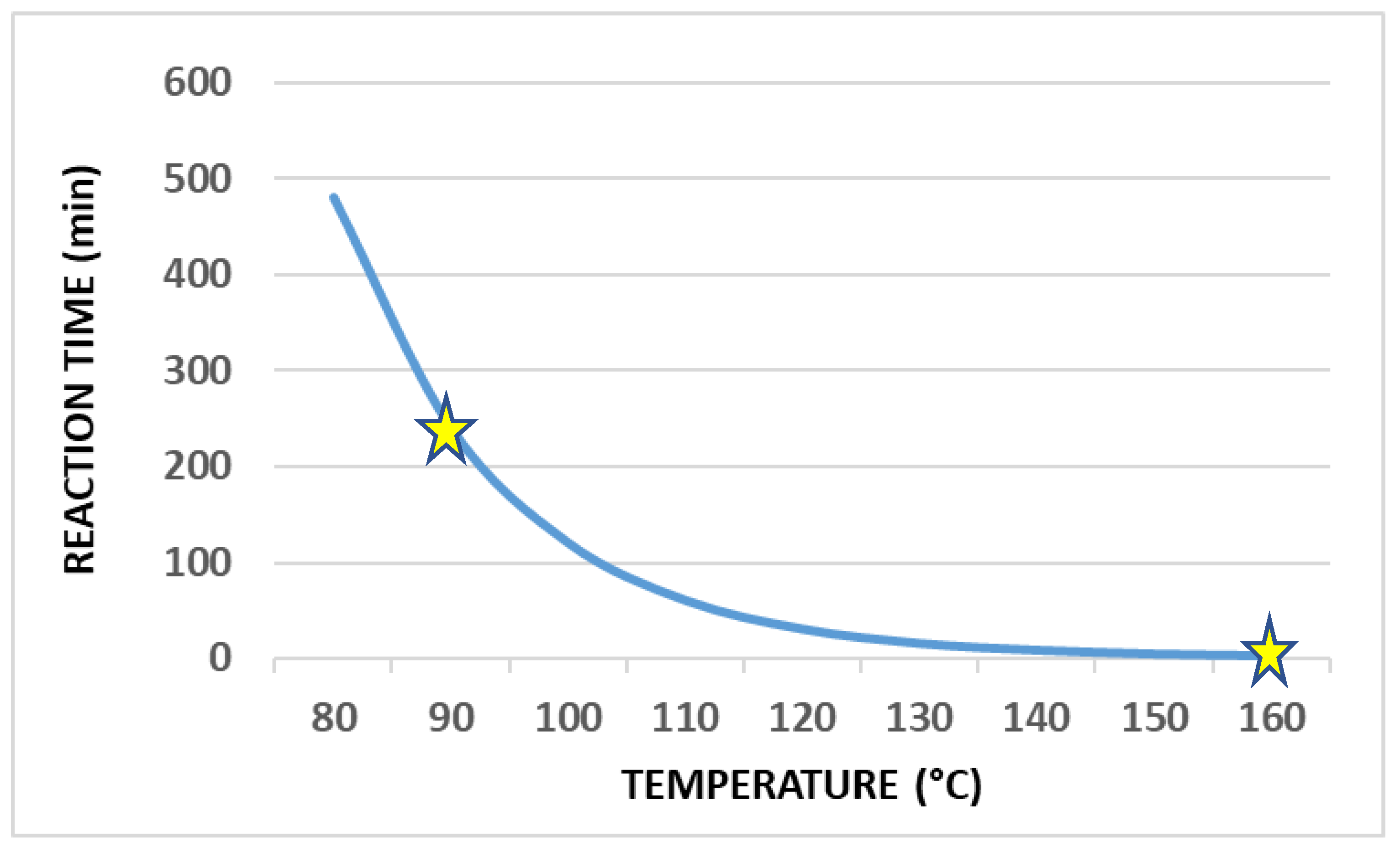

1. Microwaves Interaction with Matter

2. Microwaves and Chemical Reactions

3. Microwaves in Inorganic Chemistry

- Rapid heating to temperature of reaction;

- Increased reaction kinetics;

- Elimination of metastable phases;

- Forming of novel phases;

- High-purity products;

- Uniform nanosized powder;

- Novel crystalline morphologies.

4. Pure Oxides

4.1. ZnO

4.2. CeO2

4.3. TiO2

4.4. Iron Oxides

4.5. ZrO2-Based Oxides

4.6. Other Metal Oxides

5. Mixed Oxides

5.1. Mixed Oxides and Perovskites

5.2. Composites

6. Phosphates, Zeolites, and Miscellaneous

7. Metastable Phases

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Metaxas, C.; Meredith, R. Industrial Microwave Heating; Peter Peregrinus/IEE: Stevenage, UK, 1983; Reprint in 1988 and 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Thostenson, E.T.; Chou, T.-W. Microwave processing: Fundamentals and applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 1999, 30, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, G.; Carnaroglio, D. Microwave Chemistry; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanari, F.; Muntoni, G.; Dachena, C.; Carta, R.; Desogus, F. Microwave Heating Improvement: Permittivity Characterization of Water–Ethanol and Water–NaCl Binary Mixtures. Energies 2020, 13, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Banik, B.K. Microwaves in Chemistry Applications: Fundamentals, Methods and Future Trends; Advances in Green and Sustainable Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 9780128228951. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Yan, W. Microwave-assisted Inorganic Syntheses. In Modern Inorganic Synthetic Chemistry; Xu, R., Pang, W., Huo, Q., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi, S.; Matsuzaki, S.; Mitani, T.; Serpone, N. Microwave frequency effects on dielectric properties of some common solvents and on microwave-assisted syntheses: 2-Allylphenol and the C12–C2–C12 Gemini surfactant. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2012, 81, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezahegn, Y.A.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S.; Pedrow, P.D.; Hong, Y.-K.; Lin, H.; Tang, Z. Dielectric properties of water relevant to microwave assisted thermal pasteurization and sterilization of packaged foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 74, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuerga, D. Microwave–Material Interactions and Dielectric Properties: Key Ingredients for Mastery of Chemical Microwave Processes. In Microwaves in Organic Synthesis; Loupy, A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. Unlocking Potentials of Microwaves for Food Safety and Quality. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, E1776–E1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Tang, J.; Jiao, Y.; Bohnet, S.G.; Barrett, D.M. Dielectric Properties of Tomatoes Assisting in the Development of Microwave Pasteurization and Sterilization Processes. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 54, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binner, J.G.P.; Al-Dawery, I.A.; Aneziris, C.; Cross, T.E. Use of the Inverse Temperature Profile in Microwave Processing of Advanced Ceramics. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 1992, 269, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, P.; Colombini, E.; Canarslan, Ö.S.; Baldi, G.; Leonelli, C. Procedure to generate a selection chart for microwave sol-gel synthesis of nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2023, 189, 109383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priecel, P.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.A. Advantages and Limitations of Microwave Reactors: From Chemical Synthesis to the Catalytic Valorization of Biobased Chemicals. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdał, D.; Prociak, A. Microwave-Enhanced Polymer Chemistry and Technology; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, C.O.; Stadler, A.; Dallinger, D. Microwaves in Organic and Medicinal Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Lathwal, A.; Agarwal, S.; Nath, M. Microwave-Accelerated Approaches to Diverse Xanthenes: A Review. Curr. Microw. Chem. 2020, 7, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; John, S.E.; Shankaraiah, N. Microwave-Assisted Multicomponent Reactions in Heterocyclic Chemistry and Mechanistic Aspects. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 819–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Chia, L.H.L.; Boey, F.Y.C. Thermal and Nonthermal Interaction of Microwave Radiation with Materials. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 5321–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz, A.; Díaz-Ortiz, A.; Moreno, A. Review on Non-Thermal Effects of Microwave Irradiation in Organic Synthesis. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 2006, 41, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz, A.; Díaz-Ortiz, A.; Moreno, A. Microwaves in Organic Synthesis: Thermal and Non-Thermal Microwave Effects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreux, L.; Loupy, A.; Petit, A. Nonthermal Effects of Microwaves in Organic Synthesis. In Microwaves in Organic Synthesis; de la Hoz, A., Loupy, A., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, R.; Trombi, L.; Veronesi, P.; Leonelli, C. Microwave Energy Application to Combustion Synthesis: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advancements and Most Promising Perspectives. Int. J. Self-Propag. High-Temp. Synth. 2017, 26, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarneni, S.; Roy, R. Titania Gel Spheres by a New Sol–Gel Process. Mater. Lett. 1985, 3, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarneni, S. Microwave Memories. Chem. World 2009, 6, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli, C.; Komarneni, S. Inorganic Syntheses Assisted by Microwave Heating. Inorganics 2015, 3, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarneni, S.; Roy, R.; Li, Q.H. Microwave-Hydrothermal Synthesis of Ceramic Powders. Mater. Res. Bull. 1992, 27, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, J.W.; Kazonich, G.; McGill, S.L. Microwave heating characteristics of selected minerals and compounds. Miner. Metall. Process. 1988, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Samyal, R.; Bedi, R.; Bagha, A.K. Comparative Performance of Various Susceptor Materials and Vertical Cavity Shapes for Selective Microwave Hybrid Heating (SMHH). Phys. Scr. 2022, 97, 125704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, K.; Cravotto, G.; Varma, R.S. Impact of Microwaves on Organic Synthesis and Strategies toward Flow Processes and Scaling Up. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 13857–13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Sehgal, S.; Kumar, H. Optimization of Elemental Weight % in Microwave-Processed Joints of SS304/SS316 Using Taguchi Philosophy. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 19, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.J.; Vaidhyanathan, B.; Ganguli, M.; Ramakrishnan, P.A. Synthesis of Inorganic Solids Using Microwaves. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonelli, C.; Łojkowski, W. Main Development Directions in the Application of Microwave Irradiation to the Synthesis of Nanopowders. Chem. Today 2007, 25, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

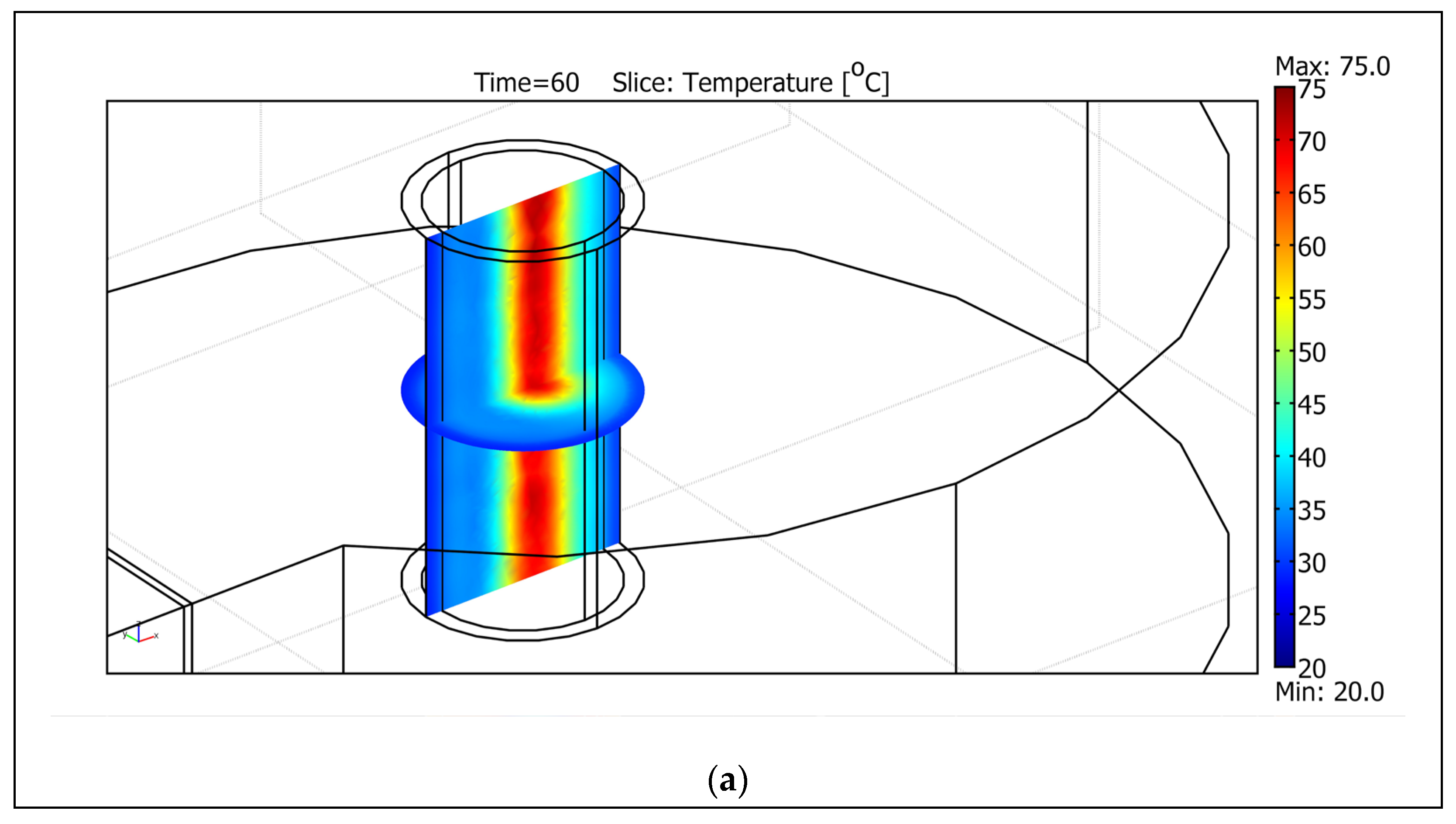

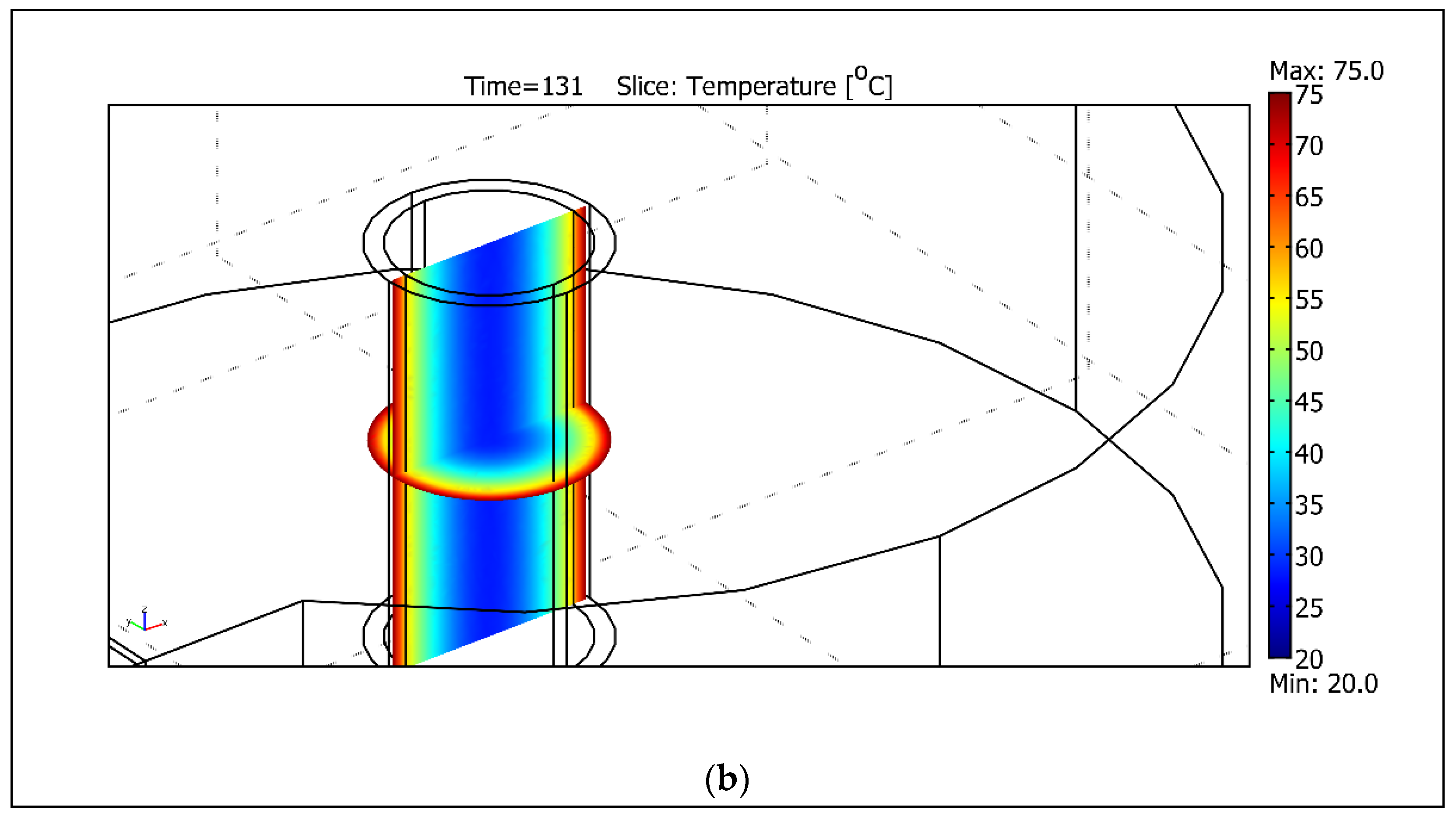

- Leonelli, C.; Łojkowski, W.; Veronesi, P. Temperature Profile within a Microwave-Irradiated Batch Reactor. J. Mach. Constr. Maint. 2018, 3, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lojkowski, W.; Gedanken, A.; Grzanka, E.; Opalinska, A.; Strachowski, T.; Pielaszek, R.; Tomaszewska-Grzeda, A.; Yatsunenko, S.; Godlewski, M.; Matysiak, H.; et al. Solvothermal Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Zinc Oxide Doped with Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+ and Cr3+ Ions. J. Nanopart. Res. 2009, 11, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicollet, C.; Carrillo, A.J. Back to Basics: Synthesis of Metal Oxides. J. Electroceram. 2024, 52, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Ponzoni, C.; Leonelli, C. Direct Energy Supply to the Reaction Mixture during Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal and Combustion Synthesis of Inorganic Materials. Inorganics 2014, 2, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trocino, S.; Prakash, T.; Jayaprakash, J.; Donato, A.; Neri, G.; Donato, N. Electrical Characterization of Nanostructured Sn-Doped ZnO Gas Sensors. In Sensors; Compagnone, D., Baldini, F., Di Natale, C., Betta, G., Siciliano, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, T.; Neri, G.; Bonavita, A.; Ranjith Kumar, E.; Gnanamoorthi, K. Structural, Morphological and Optical Properties of Bi-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized by a Microwave Irradiation Method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 4913–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionco, C.; Fabbri, D.; Calza, P.; Paganini, M.C. Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Tests of N-Doped Zinc Oxide: A New Interesting Photocatalyst. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 4129864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garino, N.; Limongi, T.; Dumontel, B.; Canta, M.; Racca, L.; Laurenti, M.; Castellino, M.; Casu, A.; Falqui, A.; Cauda, V. A Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanocrystals Finely Tuned for Biological Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garino, N.; Sanvitale, P.; Dumontel, B.; Laurenti, M.; Colilla, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Cauda, V.; Vallet-Regí, M. Zinc Oxide Nanocrystals as a Nanoantibiotic and Osteoinductive Agent. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 11312–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier di Confiengo, G.; Faga, M.G.; La Parola, V.; Magnacca, G.; Paganini, M.C.; Testa, M.L. Microwave Approach and Thermal Decomposition: A Sustainable Way to Produce ZnO Nanoparticles with Different Chemo-Physical Properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 321, 129485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natile, M.M.; Boccaletti, G.; Glisenti, A. Properties and reactivity of nanostructured CeO2 powders: Comparison among two synthesis procedures. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 6272–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natile, M.M.; Glisenti, A. Nanostructured CeO2 powders by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2006, 13, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamartini Corradi, A.; Bondioli, F.; Ferrari, A.M.; Manfredini, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanosized Ceria Powders by Microwave–Hydrothermal Method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2006, 41, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondolini, A.; Mercadelli, E.; Sanson, A.; Albonetti, S.; Doubova, L.; Boldrini, S. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Gadolinia-Doped Ceria Powders for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadelli, E.; Ghetti, G.; Sanson, A.; Bonelli, R.; Albonetti, S. Synthesis of CeO2 Nano-Aggregates of Complex Morphology. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salusso, D.; Grillo, G.; Manzoli, M.; Signorile, M.; Zafeiratos, S.; Barreau, M.; Damin, A.; Crocellà, V.; Cravotto, G.; Bordiga, S. CeO2 Frustrated Lewis Pairs Improving CO2 and CH3OH Conversion to Monomethylcarbonate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15396–15408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballauri, S.; Sartoretti, E.; Castellino, M.; Armandi, M.; Piumetti, M.; Fino, D.; Russo, N.; Bensaid, S. Mesoporous Ceria and Ceria–Praseodymia as High Surface Area Supports for Pd-Based Catalysts with Enhanced Methane Oxidation Activity. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conciauro, F.; Filippo, E.; Carlucci, C.; Vergaro, V.; Baldassarre, F.; D’Amato, R.; Terranova, G.; Lorusso, C.; Congedo, P.M.; Scremin, B.F.; et al. Properties of Nanocrystals-Formulated Aluminosilicate Bricks. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2015, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Santangelo, S.; Fazio, E.; Neri, F.; D’Arienzo, M.; Morazzoni, F.; Zhang, Y.; Pinna, N.; Russo, P.A. Stabilization of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles at the Surface of Carbon Nanomaterials Promoted by Microwave Heating. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 14901–14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippo, E.; Carlucci, C.; Capodilupo, A.L.; Perulli, P.; Conciauro, F.; Corrente, G.A.; Gigli, G.; Ciccarella, G. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Pure Anatase TiO2 and Pt–TiO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Microwave Assisted Route. Mater. Res. 2015, 18, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippo, E.; Carlucci, C.; Capodilupo, P.; Perulli, P.; Conciauro, F.; Corrente, G.A.; Gigli, G.; Ciccarella, G. Facile Preparation of TiO2–Polyvinyl Alcohol Hybrid Nanoparticles with Improved Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 331, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Wu, Z.; Tong, Y.; Cravotto, G. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Carbon-Based (N, Fe)-Codoped TiO2 for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Formaldehyde. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kőrösi, L.; Bognár, B.; Bouderias, S.; Castelli, A.; Scarpellini, A.; Pasquale, L.; Prato, M. Highly-Efficient Photocatalytic Generation of Superoxide Radicals by Phase-Pure Rutile TiO2 Nanoparticles for Azo Dye Removal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 493, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, B.; Miglietta, M.L.; Polichetti, T.; Massera, E.; Veneri, P.D. Titanium Dioxide Doped Graphene for Ethanol Detection at Room Temperature. In Sensors and Microsystems; Di Francia, G., Di Natale, C., Eds.; AISEM 2020; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 753, pp. 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Rosa, R.; Baldi, G.; Dami, V.; Cioni, A.; Lorenzi, G.; Leonelli, C. Effect of isopropanol co-product on the long-term stability of TiO2 nanoparticle suspensions produced by microwave-assisted synthesis. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 159, 108242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Rosa, R.; Baldi, G.; Dami, V.; Cioni, A.; Lorenzi, G.; Leonelli, C. Microwave-Assisted Vacuum Synthesis of TiO2 Nanocrystalline Powders in One-Pot, One-Step Procedure. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Mortalò, C.; Russo, P.; Zin, V.; Miorin, E.; Montagner, F.; Leonelli, C.; Deambrosis, S.M. Facile and Effective Method for the Preparation of Sodium Alginate/TiO2 Bio-Composite Films for Different Applications. Macromol. Symp. 2024, 413, 2300230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Plaza-González, P.J.; Baldi, G.; Catalá-Civera, J.M.; Leonelli, C. On the use of microwaves during combustion/calcination of N-doped TiO2 precursor: An EMW absorption study combined with TGA-DSC-FTIR results. Mater. Lett. 2023, 338, 133975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Lassinantti Gualtieri, M.; Veronesi, P.; Dami, V.; Lorenzi, G.; Cioni, A.; Baldi, G.; Leonelli, C. Crucible Effect on Phase Transition Temperature during Microwave Calcination of a N-Doped TiO2 Precursor: Implications for the Preparation of TiO2 Nanophotocatalysts. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 5448–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, C.; Scremin, B.F.; Sibillano, T.; Giannini, C.; Filippo, E.; Perulli, P.; Capodilupo, A.L.; Corrente, G.A.; Ciccarella, G. Microwave-assisted synthesis of boron-modified TiO2 nanocrystals. Inorganics 2014, 2, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spepi, A.; Duce, C.; Ferrari, C.; González-Rivera, J.; Jagličić, Z.; Domenici, V.; Pineider, F.; Tiné, M.R. A simple and versatile solvothermal configuration to synthesize superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles using a coaxial microwave antenna. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhyuddin, M.; Testa, D.; Lorenzi, R.; Vanacore, G.M.; Poli, F.; Soavi, F.; Specchia, S.; Giurlani, W.; Innocenti, M.; Rosi, L.; et al. Iron-based electrocatalysts derived from scrap tires for oxygen reduction reaction: Evolution of synthesis-structure-performance relationship in acidic, neutral and alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 433, 141254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porru, M.; Morales, M.d.P.; Gallo-Cordova, A.; Espinosa, A.; Moros, M.; Brero, F.; Mariani, M.; Lascialfari, A.; Ovejero, J.G. Tailoring the Magnetic and Structural Properties of Manganese/Zinc Doped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles through Microwaves-Assisted Polyol Synthesis. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, G.M.; Hamawandi, B.; Vogt, C.; Gunaratna, K.; Rajarao, R.; Toprak, M.S. Click Chemical Assembly and Validation of Bio-Functionalized Superparamagnetic Hybrid Microspheres. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, G.M.; Hamawandi, B.; Demir, M.A.; Yazgan, I.; Toprak, M.S. A Versatile Strategy to Synthesize Sugar Ligand Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Investigation of Their Antibacterial Activity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 613, 126086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, G.M.; Kakadiya, R.; Ansari, S.R.; Teleki, A.; Toprak, M.S. Magnetoresponsive Fluorescent Core–Shell Nanoclusters for Biomedical Applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekseriwattana, W.; Silvestri, N.; Brescia, R.; Tiryaki, E.; Barman, J.; Mohammadzadeh, F.G.; Jarmouni, N.; Pellegrino, T. Shape-Control in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: A Fast Route to Size-Tunable Iron Oxide Nanocubes with Benchmark Magnetic Heat Losses. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsolaro, F.; Garello, F.; Cavallari, E.; Magnacca, G.; Trukhan, M.V.; Valsania, M.C.; Cravotto, G.; Terreno, E.; Martina, K. Amphoteric β-Cyclodextrin Coated Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles: New Insights into Synthesis and Application in MRI. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioli, F.; Ferrari, A.M.; Leonelli, C.; Siligardi, C.; Pellacani, G.C. Microwave-hydrothermal synthesis of nanocrystalline zirconia powders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 2728–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioli, F.; Ferrari, A.M.; Braccini, S.; Leonelli, C.; Pellacani, G.C.; Opalińska, A.; Chudoba, T.; Grzanka, E.; Palosz, B.F.; Łojkowski, W. Microwave–hydrothermal synthesis of nanocrystalline Pr-doped zirconia powders at pressures up to 8 MPa. Solid State Phenom. 2003, 94, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioli, F.; Leonelli, C.; Manfredini, T.; Ferrari, A.M.; Caracoche, M.C.; Rivas, P.C.; Rodríguez, A.M. Microwave-hydrothermal synthesis and hyperfine characterization of praseodymium-doped nanometric zirconia powders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 88, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, A.; Leonelli, C.; Corradi, A.; Caponetti, E.; Martino, D.C.; Nasillo, G.; Saladino, M.L. Structural Characterization of Zirconia Nanoparticles Prepared by Microwave-Hydrothermal Synthesis. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2009, 30, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, A.; Corradi, A.; Leonelli, C.; Rosa, R.; Pielaszek, R.; Łojkowski, W. Microwave Technique Applied to the Hydrothermal Synthesis and Sintering of Calcia Stabilized Zirconia Nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, V.; Boccaccini, D.; Cannio, M.; Maioli, M.; Valle, M.; Romagnoli, M.; Mortalò, C.; Leonelli, C. Insight into t→m Transition of MW Treated 3Y-PSZ Ceramics by Grazing Incidence X-Ray Diffraction. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordana, A.; Pizzolitto, C.; Ghedini, E.; Signoretto, M.; Operti, L.; Cerrato, G. Innovative Synthetic Approaches for Sulphate-Promoted Catalysts for Biomass Valorisation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, A.B.; Bondioli, F.; Ferrari, A.M.; Focher, B.; Leonelli, C. Synthesis of silica nanoparticles in a continuous-flow microwave reactor. Powder Technol. 2006, 167, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, T.; Pinna, N.; Bonavita, A.; Micali, G.; Rizzo, G.; Neri, G. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Metal Oxide Nanostructures for Sensing Applications. In Sensors and Microsystems; Neri, G., Donato, N., d’Amico, A., Di Natale, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 91, pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya Raj, D.; Krishnakumar, T.; Jayaprakash, R.; Prakash, T.; Leonardi, G.; Neri, G. CO Sensing Characteristics of Hexagonal-Shaped CdO Nanostructures Prepared by Microwave Irradiation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 171–172, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, N.; Kannan, J.C.; Krishnakumar, T.; Leonardi, S.G.; Neri, G. Sensing Behavior to Ethanol of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles Prepared by Microwave Synthesis with Different Irradiation Time. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 194, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondioli, F.; Corradi, A.B.; Ferrari, A.M.; Leonelli, C.; Siligardi, C.; Manfredini, T.; Evans, N.G. Microwave synthesis of Al2O3/Cr2O3 (SS) ceramic pigments. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 1998, 33, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonometti, E.; Castiglioni, M.; Lausarot, P. Solid-state mixed oxides synthesis under microwave heating (JMSL10627-04). J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 6485–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbizzani, C.; Beninati, S.; Damen, L.; Mastragostino, M. Power and temperature controlled microwave synthesis of SVO. Solid State Ion. 2007, 178, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barison, S.; Fabrizio, M.; Fasolin, S.; Montagner, F.; Mortalò, C. A microwave-assisted sol–gel Pechini method for the synthesis of BaCe0.65Zr0.20Y0.15O3−δ powders. Mater. Res. Bull. 2010, 45, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, S.; Mortalò, C.; Fasolin, S.; Agresti, F.; Doubova, L.; Fabrizio, M.; Barison, S. Influence of microwave-assisted Pechini method on La0.80Sr0.20Ga0.83Mg0.17O3−δ ionic conductivity. Fuel Cells 2012, 12, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, C.; Rosa, R.; Cannio, M.; Buscaglia, V.; Finocchio, E.; Nanni, P.; Leonelli, C. Optimization of BFO microwave-hydrothermal synthesis: Influence of process parameters. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 558, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, C.; Cannio, M.; Boccaccini, D.N.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Agersted, K.; Leonelli, C. Ultrafast microwave hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of Bi1−xLaxFeO3 micronized particles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 162, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, A.; Mozzati, M.C.; Albini, B.; Galinetto, P.; Bini, M. Role of non-magnetic dopants (Ca, Mg) in GdFeO3 perovskite nanoparticles obtained by different synthetic methods: Structural, morphological and magnetic properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 18263–18277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xue, Y.; He, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Z.; Cravotto, G. Surfactants-assisted preparation of BiVO4 with novel morphologies via microwave method and CdS decoration for enhanced photocatalytic properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 122019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortalò, C.; Rosa, R.; Veronesi, P.; Fasolin, S.; Zin, V.; Deambrosis, S.M.; Miorin, E.; Dimitrakis, G.; Fabrizio, M.; Leonelli, C. Microwave Assisted Sintering of Na-β″-Al2O3 in Single Mode Cavities: Insights in the Use of 2450 MHz Frequency and Preliminary Experiments at 5800 MHz. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28767–28777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Agli, G.; Mascolo, M.C.; Mascolo, G. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Precursors for Y-TZP/α-Al2O3 Composite. Powder Technol. 2004, 148, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barison, S.; Fabrizio, M.; Mortalò, C.; Antonucci, P.L.; Modafferi, V.; Gerbasi, R. Novel Ru/La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.5Mn0.5O3−δ catalysts for propane reforming in IT-SOFCs. Solid State Ion. 2010, 181, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, G.; Leonardi, S.G.; Latino, M.; Donato, N.; Baek, S.; Conte, D.E.; Russo, P.A.; Pinna, N. Sensing Behavior of SnO2/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites toward NO2. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 179, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yan, Y.; Cravotto, G.; Wu, Z. Microwave-Induced Crystallization of AC/TiO2 for Improving the Performance of Rhodamine B Dye Degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 351, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garino, N.; Sacco, A.; Castellino, M.; Muñoz-Tabares, J.A.; Armandi, M.; Chiodoni, A.; Pirri, C.F. One-pot microwave-assisted synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/iron oxide nanocomposite catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Sel. 2016, 1, 3640–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, A.; Leonelli, C.; Dell’Anna, M.M.; Romanazzi, G.; Mali, M.; Catauro, M.; Mastrorilli, P. Microwave-assisted solvothermal controlled synthesis of Fe–Co composite material. Macromol. Symp. 2021, 395, 2000196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, A.; Dipalo, M.C.; Allegretta, I.; Terzano, R.; Cioffi, N.; Mastrorilli, P.; Mali, M.; Romanazzi, G.; Nacci, A.; Dell’Anna, M.M. Microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis of Fe3O4/CeO2 nanocomposites and their catalytic activity in the imine formation from benzyl alcohol and aniline. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, P.; Bettini, S.; Sawalha, S.; Pal, S.; Licciulli, A.; Marzo, F.; Lovergine, N.; Valli, L.; Giancane, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline by ZnO/γ-Fe2O3 Paramagnetic Nanocomposite Material. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, J.; Spepi, A.; Ferrari, C.; Tovar-Rodriguez, J.; Fantechi, E.; Pineider, F.; Vera-Ramírez, M.A.; Tiné, M.R.; Duce, C. Magnetothermally-responsive nanocarriers using confined phosphorylated halloysite nanoreactor for in situ iron oxide nanoparticle synthesis: A MW-assisted solvothermal approach. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 635, 128116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellino, M.; Sacco, A.; Fontana, M.; Chiodoni, A.; Pirri, C.F.; Garino, N. The Effect of Sulfur and Nitrogen Doping on the Oxygen Reduction Performance of Graphene/Iron Oxide Electrocatalysts Prepared by Using Microwave-Assisted Synthesis. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Mortalò, C.; Zin, V.; Armetta, F.; Boiko, V.; Hreniak, D.; Zapparoli, M.; Deambrosis, S.M.; Miorin, E.; Leonelli, C.; et al. Eu-Doped YPO4 Luminescent Nanopowders for Anticounterfeiting Applications: Tuning Morphology and Optical Properties by a Rapid Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Method. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 6893–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Mortalò, C.; Zin, V.; Deambrosis, S.M.; Zapparoli, M.; Miorin, E.; Leonelli, C. Understanding the Effect of Temperature on the Crystallization of Eu3+:YPO4 Nanophosphors Prepared by MW-Assisted Method. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 7075–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armetta, F.; Boiko, V.; Hreniak, D.; Mortalò, C.; Leonelli, C.; Barbata, L.; Saladino, M.L. Effect of Hydrothermal Time on the Forming Specific Morphology of YPO4:Eu3+ Nanoparticles for Dedicated Luminescent Applications as Optical Markers. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 23287–23294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, E.; Mortalò, C.; Andreola, F.; Zin, V.; Capelli, R.; Pasquali, L.; Deambrosis, S.M.; Miorin, E.; Leonelli, C. Stable Water-Based Luminescent Suspensions of Eu3+:YPO4 Nanophosphors in Sodium Alginate Medium: Sustainable Inks for Potential Anticounterfeiting Applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 58745–58755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Proverbio, E. Microwave assisted crystallization of zeolite A from dense gels. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 247, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Proverbio, E. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Zeolite LTA by Microwave Irradiation. Mater. Res. Innov. 2004, 8, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Proverbio, E. Influence of process parameters in microwave continuous synthesis of zeolite LTA. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2008, 112, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Calabrese, L.; Freni, A.; Proverbio, E. Hydrothermal and microwave synthesis of SAPO (CHA) zeolites on aluminium foams for heat pumping applications. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2013, 167, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferone, C.; Esposito, S.; Pansini, M. Microwave assisted hydrothermal conversion of Ba-exchanged zeolite A into metastable paracelsian. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2006, 96, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Freni, A.; Proverbio, E.; Restuccia, G.; Russo, F. Zeolite coated copper foams for heat pumping applications. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2006, 91, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Ghedini, E.; Menegazzo, F.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Peurla, M.; Zendehdel, M.; Cruciani, G.; Di Michele, A.; Murzin, D.Y.; Signoretto, M. CuZSM-5@HMS Composite as an Efficient Micro-Mesoporous Catalyst for Conversion of Sugars into Levulinic Acid. Catal. Today 2022, 390–391, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Rosa, R.; Corradi, A.; Leonelli, C. Microwaves-Mediated Preparation of Organoclays as Organic-/Bio-Inorganic Hybrid Materials. Curr. Org. Chem. 2011, 15, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, K.; Tagliapietra, S.; Barge, A.; Cravotto, G. Combined Microwaves/Ultrasound, a Hybrid Technology. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, R.C.; Ahmad, I.; Clark, D.E. Combustion Synthesis Using Microwave Energy. Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc. 1990, 11, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.; Agrawal, D.; Cheng, J.; Gedevanishvili, S. Full Sintering of Powdered-Metal Bodies in a Microwave Field. Nature 1999, 399, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, P.; Rosa, R.; Colombini, E.; Leonelli, C.; Poli, G.; Casagrande, A. Microwave Assisted Combustion Synthesis of Non-Equilibrium Intermetallic Compounds. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energ. 2010, 44, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.; Veronesi, P.; Casagrande, A.; Leonelli, C. Microwave Ignition of the Combustion Synthesis of Aluminides and Field-Related Effects. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 657, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Veronesi, P. Functionally Graded Materials. In Functionally Graded Materials Obtained by Combustion Synthesis Techniques: A Review; Reynolds, N.J., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Chapter 2; pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Colombini, E.; Rosa, R.; Veronesi, P.; Poli, G.; Leonelli, C. Microwave Ignited Combustion Synthesis as a Joining Technique for Dissimilar Materials: Modeling and Experimental Results. Int. J. Self-Propag. High-Temp. Synth. 2012, 21, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, G.; Sola, R.; Veronesi, P. Microwave-Assisted Combustion Synthesis of NiAl Intermetallics in a Single Mode Applicator: Modeling and Optimisation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 441, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.; Veronesi, P.; Leonelli, C. A Review on Combustion Synthesis Intensification by Means of Microwave Energy. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2013, 71, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, P.; Leonelli, C.; Poli, G.; Casagrande, A. Enhanced Reactive NiAl Coatings by Microwave-Assisted SHS. COMPEL 2008, 27, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, P.; Colombini, E.; Rosa, R.; Leonelli, C.; Garuti, M. Microwave Processing of High Entropy Alloys: A Powder Metallurgy Approach. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 122, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombi, L.; Cugini, F.; Rosa, R.; Amadè, N.S.; Chicco, S.; Solzi, M.; Veronesi, P. Rapid Microwave Synthesis of Magnetocaloric Ni–Mn–Sn Heusler Compounds. Scr. Mater. 2020, 176, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, E.; Rosa, R.; Trombi, L.; Zadra, M.; Casagrande, A.; Veronesi, P. High Entropy Alloys Obtained by Field Assisted Powder Metallurgy Route: SPS and Microwave Heating. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 210, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, E.; Lassinantti Gualtieri, M.; Rosa, R.; Tarterini, F.; Zadra, M.; Casagrande, A.; Veronesi, P. SPS-Assisted Synthesis of SiCp Reinforced High Entropy Alloys: Reactivity of SiC and Effects of Pre-Mechanical Alloying and Post-Annealing Treatment. Powder Metall. 2018, 61, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasik, M. Microwave Processing of Materials in Metallurgy. Theory Pract. Metall. 2025, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, E.; Papalia, K.; Barozzi, S.; Perugi, F.; Veronesi, P. A Novel Microwave and Induction Heating Applicator for Metal Making: Design and Testing. Metals 2020, 10, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency Range | Energy Range (eV) | Penetration Depth in Water 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 300 MHz–300 GHz | 1.24 × 10−6–1.24 × 10−3 | 30 cm–0.1 cm |

| 2450 MHz (used worldwide) | 1.01 × 10−5 | 12.25 cm |

| 5800 MHz (used worldwide) | 2.40 × 10−5 | 1.00 cm |

| Material | Penetration Depth (cm) |

|---|---|

| Metallic plate (Al, Cu, Ag, stainless steel) | 1–8 × 10−4 |

| Distilled water | 1.68 |

| Tap water | 1.25 |

| Ice * | 1100 |

| Hollow glass | 35 |

| Porcelain | 56 |

| Epoxy resin | 4100 |

| Teflon | 9200 |

| Quartz glass | 16,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonelli, C.; Colombini, E.; Mortalò, C. Contribution of Microwave Irradiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Compounds: An Italian Approach. Inorganics 2025, 13, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120410

Leonelli C, Colombini E, Mortalò C. Contribution of Microwave Irradiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Compounds: An Italian Approach. Inorganics. 2025; 13(12):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120410

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonelli, Cristina, Elena Colombini, and Cecilia Mortalò. 2025. "Contribution of Microwave Irradiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Compounds: An Italian Approach" Inorganics 13, no. 12: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120410

APA StyleLeonelli, C., Colombini, E., & Mortalò, C. (2025). Contribution of Microwave Irradiation in the Synthesis of Inorganic Compounds: An Italian Approach. Inorganics, 13(12), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120410