Abstract

Fluoride contamination in groundwater is a pressing environmental and public health issue, with chronic exposure linked to skeletal and dental fluorosis. Here, we report the synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles via a controlled co-precipitation method employing dimethylformamide (DMF) as solvent and either ammonium hydroxide (MgO-1) or ammonium carbonate (MgO-2) as precipitating agents. The resulting materials were comprehensively characterized using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA/DSC), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS). Additionally, BET surface area and porosity analyses revealed mesoporous structures, with MgO-1 showing a slightly higher surface area (14.12 m2 g−1) than MgO-2 (13.87 m2 g−1). Both MgO-1 and MgO-2 exhibited high crystallinity, nanoscale particle sizes (81.6 nm and 128.1 nm, respectively), and distinct morphological features. Batch adsorption studies revealed maximum fluoride uptake capacities of 117.6 mg/g (MgO-1) and 94.5 mg/g (MgO-2) at neutral pH, with MgO-1 exhibiting superior performance due to its smaller particle size and higher specific surface area. Fluoride removal remained above 98% between pH 3–9, confirming stability across a wide pH range, with a minor decline at pH 11 due to OH− competition. Adsorption equilibrium data were best described by the Temkin isotherm model, suggesting heterogeneous surface interactions and an exothermic process, while kinetic analyses indicated pseudo-second-order behavior for MgO-1 and pseudo-first-order for MgO-2. Both materials maintained high fluoride selectivity in the presence of competing anions and successfully reduced fluoride in tap water from 2.11 mg/L to below the WHO limits without altering water hardness. These findings underscore the potential of engineered MgO nanomaterials as efficient, selective, and sustainable adsorbents for water defluoridation, offering a promising pathway toward scalable remediation technologies in fluoride-affected regions.

1. Introduction

Fluoride contamination in groundwater remains a critical environmental and public health problem worldwide. It is estimated that around two hundred million people live in regions affected by excessive fluoride levels, especially in developing nations such as Mexico, China, India, and Pakistan [1,2]. Prolonged exposure to fluoride concentrations above the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline of 1.5 mg L−1 can result in serious health disorders, including both dental and skeletal fluorosis [3]. Adsorption has emerged as one of the most practical and cost-effective technologies for fluoride removal, and among various adsorbents, magnesium oxide (MgO) stands out due to its high affinity for fluoride, chemical stability, and low environmental impact [4,5]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that other advanced separation processes are being actively investigated. For example, capacitive deionization (CDI) has recently been explored as a sustainable and energy-efficient alternative for fluoride removal, showing promising results for future large-scale applications [6].

Recent advances have focused on tailoring MgO nanostructures to enhance their adsorption capacity through precise control of morphology and surface chemistry. Zhang et al. synthesized flower-like hierarchical MgO structures, achieving a maximum fluoride adsorption capacity of 199.7 mg/g, supported by mechanistic evidence from SEM, BET, FTIR, and XPS analyses [7]. Similarly, Shi et al. reported that layered MgO could remove approximately 92% of fluoride from groundwater, with mechanisms involving hydroxyl exchange and the formation of surface Mg(OH)2 [8].

Other studies have demonstrated that activating MgO through thermal treatment enhances its surface area and reactivity. Cao et al. found that thermally activated MgO achieved over 98% fluoride removal, with adsorption capacities reaching 19.3 mg/g and removal mechanisms confirmed through FTIR and XPS [9]. Zhang et al. compared unmodified and lanthanum-doped spheroidal MgO, finding that La-modification significantly improved fluoride uptake due to increased surface complexation sites [10].

Hybrid adsorbents combining MgO with porous or carbon-based materials have also shown promise. Wan et al. embedded nano-MgO into biochar matrices, increasing fluoride accessibility and stability, with maximum adsorption capacities around 83 mg/g [11]. Likewise, Yang et al. incorporated nanostructured MgO into activated carbon, achieving over 95% fluoride removal due to increased surface functionality and dispersion [12]. Beyond structural optimization, MgO-based materials have also been evaluated for multi-contaminant removal. Sugita et al. explored MgO, Mg(OH)2, and MgCO3 for the simultaneous removal of fluoride and arsenate, confirming that adsorption involved both ion exchange and surface precipitation [13]. López-Castillo et al. compared MgFe-based hydrotalcites and oxides, concluding that mesoporous MgFe oxides exhibit high fluoride affinity through Langmuir-type monolayer adsorption [14].

Parallel developments in metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and bimetallic oxides have provided valuable insight into metal–fluoride interactions and anion-exchange mechanisms. For instance, hierarchical Ca–Al MOFs have demonstrated enhanced fluoride affinity due to the presence of coordinatively unsaturated metal centers and hierarchical porosity [15]. These findings help rationalize the relevance of surface hydroxyl exchange and metal–fluoride coordination in explaining the adsorption behavior observed for MgO-based systems.

This study aimed to synthesize and characterize magnesium oxide nanoparticles prepared via the coprecipitation route employing dimethylformamide (DMF) and ammonia as solvent and precipitating agent, respectively. The defluoridation performance of the synthesized MgO materials was systematically evaluated through batch adsorption experiments, encompassing the construction of adsorption isotherms, kinetic modeling, and the examination of the influence of competing ions and water hardness before and after fluoride removal.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Thermal Analysis of MgO Precursors

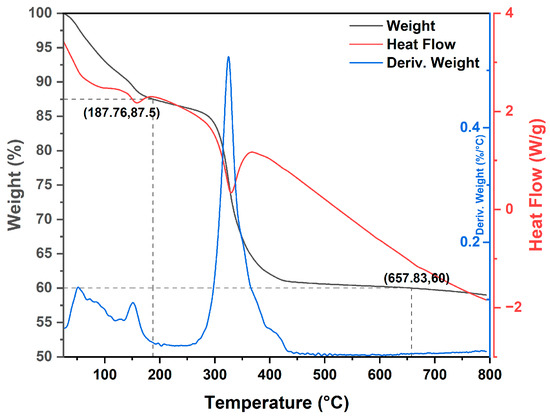

Thermal analysis profiles were conducted on MgO-1 and MgO-2 precursors. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curves of decomposition and phase changeover of as-synthesized magnesium precipitates to MgO nanoparticles. In the thermogravimetric (TGA) study, both the mass-loss percentage and its first derivative were plotted as functions of temperature. This approach allowed precise identification of the decomposition products and the corresponding temperature intervals in which these processes occurred. Figure 1 displays the TGA profile of the MgO-1 precursor, illustrating the proposed stages of thermal decomposition. The curve exhibits two clearly distinguishable steps, indicating successive mass-loss events associated with specific physicochemical transformations.

Figure 1.

TGA/DSC curve of the thermal decomposition of MgO-1 precursor.

Figure 2.

TGA/DSC curve of the thermal decomposition of MgO-2 precursor.

The first decomposition stage (A) occurs within the temperature interval of 25–178 °C, accompanied by a 12.50% reduction in mass. This weight loss is attributed to the release of hydration water molecules physically adsorbed and chemisorbed on the precursor surface [16]. The second stage (B), spanning 178–430 °C, corresponds to the thermal decomposition of Mg(OH)2, leading to the generation of MgO and H2O [17]. The observed mass loss of 27.50% is in close agreement with the theoretical value of 26.75%, confirming this transformation. Moreover, a distinct endothermic peak near 330 °C in the DSC trace supports the conversion of Mg(OH)2 to MgO [18].

The TGA profile of the MgO-2 precursor (Figure 2) also exhibits two separate stages of thermal decomposition, indicating a similar stepwise transformation pattern. The first decomposition stage (A) was detected in the temperature interval of 25–275 °C, corresponding to a 34.00% weight loss. This reduction is attributed to the removal of hydration water molecules from the precursor surface [19]. The second stage (B), observed between 275–450 °C, accounts for an additional 33.00% mass loss and is associated with the thermal decomposition of magnesium carbonate, producing carbon dioxide and forming crystalline magnesium oxide [20]. A subsequent and gradual mass decrease extending up to ≈800 °C indicates the completion of the conversion to cubic MgO and stabilization of the remaining residue. The measured residual mass of 33.00% agrees well with the theoretical MgO content expected after MgCO3 decomposition.

According to the DSC thermogram, four distinct endothermic events were recorded. Two broad peaks centered at approximately 100 °C and 150 °C correspond to the desorption of surface-bound water molecules. A sharp endothermic signal at ≈350 °C is attributed to the decomposition of MgCO3 to MgO, while a subsequent peak near 430 °C confirms the complete phase transformation and formation of thermally stable MgO [21].

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

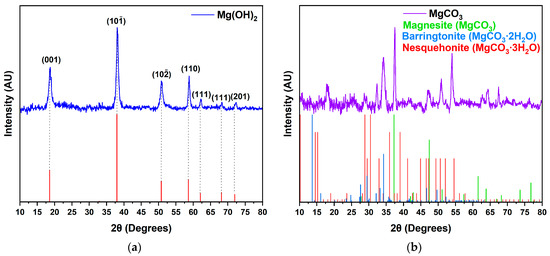

The crystal structures of the precursors and the final products were characterized via XRD (Figure 3 and Figure 4). All the reflections of the precursors of magnesium oxides (MgO-1 and MgO-2) can be indexed to a pure hexagonal phase of magnesium hydroxide (ICDD 96-210-1439) [22,23,24] and hydrated magnesium carbonate (ICDD 96-900-2820 (Magnesite), ICDD 00-020-0669 (Nesquehonite) and Barringtonite) [25,26,27].

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction spectra of the precursors of magnesium oxides: (a) MgO-1 precursor (Mg(OH)2); (b) MgO-2 precursor (Magnesite, Barringtonite * and Nesquehonite). * Data obtained from ref. [27].

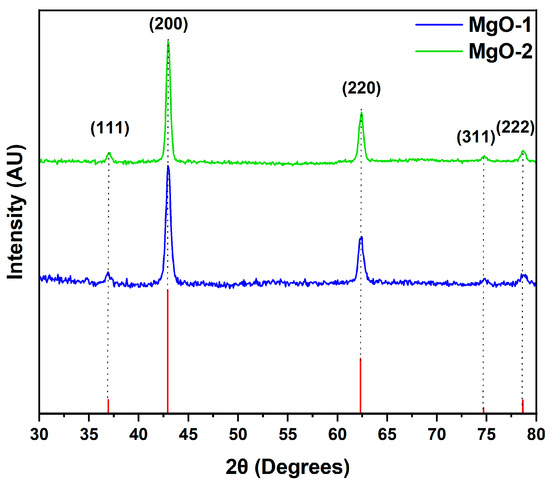

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction spectra of MgO-1 and MgO-2.

After calcination at 800 °C for 6 h, the XRD pattern exhibits well-resolved X-ray diffraction, indexed to (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222) planes of the face-centered cubic (FCC) network of MgO (JCPDS 89-4248) [28,29]. In the XRD pattern, no peaks for precursor magnesium hydroxide or carbonate were identified, confirming that the precursors were fully decomposed to MgO. Crystallite sizes of MgO nanoparticles prepared from precursors, calculated using Scherrer’s formula (FWHM of (200) and (220)), presented reduced values for MgO-1 than MgO-2. The average crystallite size of all the products fell between 29 and 39 nm, respectively.

2.3. FTIR Spectra

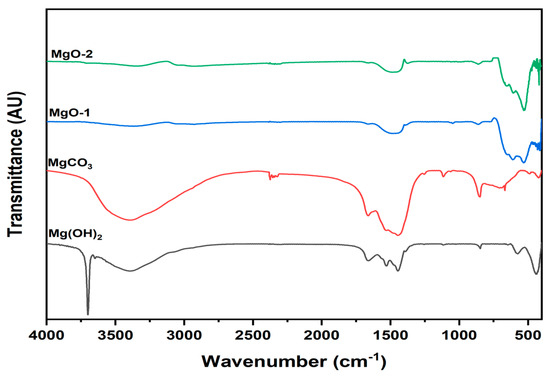

The FTIR spectra of the hydrated precursors (Mg(OH)2 and MgCO3) together with their calcined derivatives are presented in Figure 5. Broad absorption bands observed in the 3650–3000 cm−1 region correspond to the O–H stretching vibrations of water molecules in the compounds. The variations in intensity and shape among these bands are attributed to differences in the amount of crystallization water or to physically adsorbed water on the oxide surfaces [30]. The spectrum of Mg(OH)2 shows a pronounced and sharp peak at 3700 cm−1, which is assigned to the O–H stretching vibration characteristic of the hydroxyl groups in the crystal lattice. Moreover, a strong absorption near 437 cm−1 corresponds to the Mg–O stretching vibration typical of magnesium hydroxide [31]. Bending vibrations of water molecules are identified between 1529 and 1662 cm−1, confirming the presence of strongly hydrogen-bonded water within the hydrated precursors [32]. In the spectrum of MgO, weak absorption bands appear at 1661 cm−1, 3345 cm−1, and 3380 cm−1, associated with bending and stretching vibrations of adsorbed water and surface hydroxyl groups [33]. The FTIR profile of hydrated MgCO3 closely resembles that of MgCO3·3H2O, as evidenced by the characteristic carbonate absorption bands at 850 cm−1 (ν2 mode), 1115 cm−1 (ν1 mode), and 1483–1447 cm−1 (ν3 mode) [34]. After calcination, magnesium oxide exhibits only weak bands corresponding to the ν2 and ν3 modes, attributed to trace CO2 adsorption from the atmosphere. Three distinct absorption features between 415 and 610 cm−1 are assigned to the Mg–O stretching vibrations, confirming the successful formation of crystalline MgO [35].

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of hydrated precursors (Mg(OH)2 and MgCO3) and MgO-1 and MgO-2.

The disappearance or significant reduction of O–H and CO32− absorption bands after calcination indicates the successful thermal decomposition of hydroxide and carbonate precursors into pure MgO. The weak residual bands near 3400 cm−1 and 1660 cm−1 in the calcined samples correspond to physisorbed water and surface hydroxyl groups, suggesting limited moisture adsorption on the oxide surface. Moreover, the emergence of sharp Mg–O stretching vibrations between 415 and 610 cm−1 confirms the crystallization of the cubic MgO phase, in agreement with the XRD results. These observations collectively verify that the structural transformation from Mg(OH)2 and MgCO3 to MgO occurred completely during calcination, leading to well-defined oxide lattices with active surface hydroxyls that may contribute to fluoride adsorption.

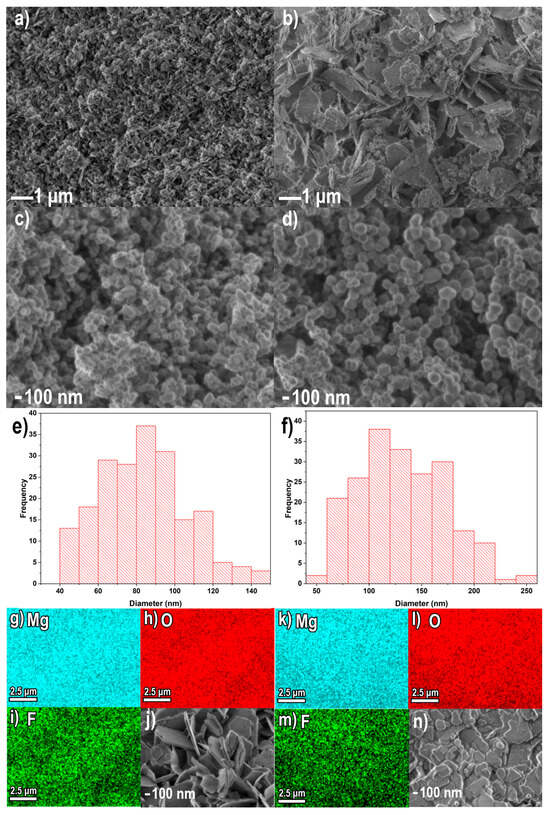

2.4. SEM/EDS

The morphological and compositional characterization of the sample was carried out by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Figure 6a shows the SEM image of the MgO-1 precursor (Mg(OH)2), revealing highly agglomerated nanoflakes with characteristic dimensions of approximately 100–200 nm. In contrast, the MgO-2 precursor (MgCO3) exhibits microflake aggregates in the range of 1–2 µm (Figure 6b). The results reveal that although the morphologies of the precursors are comparable, their particle sizes differ noticeably. This variation can be attributed to the influence of distinct anions present in the reaction medium, which modify the nucleation and crystal growth kinetics of the MgO nanostructures. As a consequence, these compositional differences lead to the formation of materials with distinct morphologies and particle dimensions [36,37]. After calcination at 800 °C for 6 h, both precursors were fully transformed into MgO nanoparticles. The resulting MgO-1 consisted of nearly spherical particles with an average diameter of 81 nm, whereas MgO-2 exhibited slightly larger and more uniform spheres averaging 128 nm (Figure 6e–f).

Figure 6.

SEM images of the precursors Mg(OH)2 (a), MgCO3 (b), MgO-1 (c), MgO-2 (d), size distribution of nanoparticles obtained from MgO-1 (e) and MgO-2 (f) precursors, EDX mapping results (g–i,k–m) and SEM images (j,n) for the materials after fluoride adsorption.

After adsorption, the formation of well-defined microflakes was observed for both adsorbents (Figure 6j,n). EDS elemental mapping images revealed that MgO-1 and MgO-2 presented a uniform distribution of Mg and O, very close to the theoretical composition of these compounds. The elemental composition was also determined after the fluoride ion adsorption process. The results obtained presented a highly uniform distribution of Mg, O and F, which confirmed the formation of fluoride precipitates on the surface of the materials (Figure 6g–i,k–m). The detailed elemental composition before and after adsorption is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of element analysis before and after fluoride adsorption.

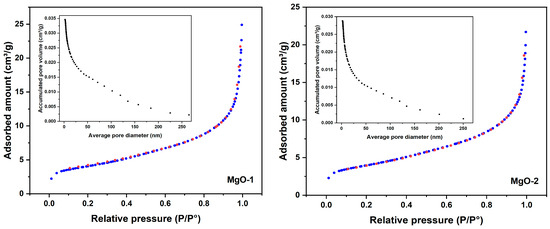

2.5. Textural Characterization by N2 Adsorption–Desorption (BET Analysis)

The textural properties of the synthesized MgO samples were evaluated by N2 adsorption–desorption analysis at 77 K, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The corresponding isotherms and pore size distribution curves are shown in Figure 7. Both MgO-1 and MgO-1 exhibit type IV isotherms with H3 hysteresis loops [38].

Table 2.

Textural parameters of MgO samples obtained from N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms.

Figure 7.

N2 adsorption (blue)–desorption (red) isotherms and BJH pore size distribution curves for MgO-1 and MgO-2, showing type IV isotherms with H3 hysteresis loops typical of mesoporous materials.

The BET surface area (), total pore volume (), and average pore diameter () were obtained from the adsorption branch of the isotherm. As listed in Table 2, MgO-1 exhibited a slightly higher surface area (14.12 m2 g−1) and pore volume (0.02999 cm3 g−1) compared with MgO-2 (13.87 m2 g−1 and 0.02582 cm3 g−1, respectively). The average pore diameters derived from the adsorption and desorption branches (12.10/13.77 nm for MgO-1 and 10.27/12.21 nm for MgO-2) confirm the mesoporous structure of both samples.

These results are consistent with previous reports on MgO nanostructures, which exhibit specific surface areas between 10.94 and 15.32 m2 g−1 and mesoporous textures [39,40]. The slightly larger surface area and pore volume of MgO-1 provide a greater number of accessible active sites for fluoride adsorption. Additionally, the mesoporous structure facilitates ion diffusion and promotes efficient contact between fluoride ions and surface hydroxyl groups, enhancing fluoride removal efficiency [41].

2.6. Adsorption Kinetics

The adsorption rate depends on the structural properties of the adsorbent, the initial fluoride ion concentration in the solution, and the interaction between fluoride ions and the active sites on the adsorbents [42]. Adsorption kinetics experiments were conducted to determine the fluoride removal rate from aqueous solutions at an initial fluoride concentration of 10 mg/L. Lagergren’s pseudo-first-order model [43] and Ho’s pseudo-second-order model [44] were tested to fit the experimental data. The mathematical formulas of the two models in nonlinear form are presented in Equations (1) and (2), respectively.

where qe and qt are the quantities of fluoride (mg/g) adsorbed on the adsorbent at equilibrium status and at a specific time respectively, and t is the contacting time (min). k1 (min−1) and k2 (g/mg·min) are the equilibrium rate constants.

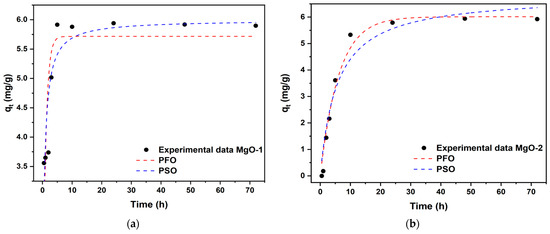

Figure 8 shows the time-dependent adsorption rate (qt) of fluoride onto magnesium oxides at room temperature and pH ≈ 6.5 from fluoride solutions with an initial concentration (C0) of 10.0 mg/g, as well as the nonlinear fits of the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) adsorption kinetics. From these graphs for MgO-1, approximately 80% of the equilibrium adsorbed fluoride (qe) occurred during the first 3 h from the start of the reaction, while for MgO-2 this occurred at around 10 h. The results show that the equilibrium time values were approximately 24 h for fluoride adsorption from C0 solution.

Figure 8.

Nonlinear kinetic fitting of fluoride adsorption onto magnesium oxides using pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order models (PSO): (a) MgO-1; (b) MgO-2.

The calculated rate constants and related parameters for the nonlinear kinetic models are listed in Table 3. A higher k1 value generally represents a faster adsorption rate, while a higher k2 value means slower adsorption. For MgO-1, the correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.8143) and a lower value of χ2 = 0.2550 can describe the experimental data of the pseudo-second-order equation fit, favoring a fluoride removal process by means of this kinetic model. On the other hand, for MgO-2, the values of R2 = 0.9765 y χ2 = 0.1663 more accurately describe the pseudo-first order kinetic model.

Table 3.

Kinetic models and estimated parameters for fluoride adsorption onto MgO-1 and MgO-2.

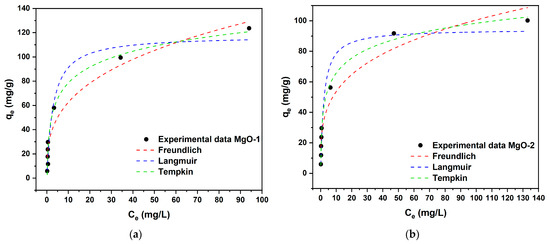

2.7. Adsorption Isotherms

To assess the adsorption performance of the synthesized materials, equilibrium adsorption isotherms were obtained at room temperature under neutral pH conditions, using initial fluoride concentrations ranging from 10 to 300 mg/L. Figure 9 presents the corresponding isotherms for MgO-1 and MgO-2. The adsorption capacity of both adsorbents increased progressively with the rise in initial fluoride concentration until reaching equilibrium, a trend attributed to the progressive saturation of available surface-active sites. Notably, MgO-1 exhibited a higher fluoride uptake than MgO-2 at concentrations above 100 mg/L, likely due to its smaller particle size and larger specific surface area, which provide a greater number of accessible adsorption sites.

Figure 9.

Nonlinear fitting of adsorption isotherms for fluoride removal: (a) MgO-1; (b) MgO-2.

Furthermore, the adsorption isotherms experimental data were simulated by the Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isotherm models [45,46,47], which were presented as:

where Ce (mg/L) is the adsorption equilibrium concentration of fluoride, qe (mg/g) is the fluoride adsorbed amount at equilibrium state, Q0max is the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), T is absolute temperature (K); R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K) and n is the Freundlich exponent related to the adsorption intensity. AT is the equilibrium binding constant corresponding to the maximum binding energy (L/g), KL (L/mol), KF (mg/g)/(mol/L)n and bT (J/mol) are the Langmuir constant, the Freundlich constant and the Temkin isotherm constant related to the heat of adsorption.

The simulation results describing fluoride adsorption behavior based on different isotherm models and their corresponding fitting parameters are summarized in Table 4. According to the calculated correlation coefficients (R2) and chi-square (χ2) values, the experimental data exhibited the best agreement with the Temkin isotherm model, indicating that the adsorption process is more accurately represented by this model than by the others (R2 ≥ 0.9817, χ2 ≤ 40.716). The values obtained from the nonlinear fits for the Temkin isotherm parameters, AT and bT were: 6.45 L/g, 131.5 J/mol (MgO-1) and 10.20 L/g, 174.5 J/mol (MgO-2). Based on these results, the present model suggests an exothermic reaction during the adsorption process since B > 0 (B = RT/bT), which is an indicator of heat release during the process [48].

Table 4.

Freundlich, Langmuir, and Temkin isotherms for the adsorption of fluoride ions onto MgO-1 and MgO-2.

According to the Langmuir isotherm model, the maximum fluoride adsorption capacities for MgO-1 and MgO-2 were determined to be 117.64 mg/g and 94.54 mg/g, respectively. In comparison with other fluoride adsorbents listed in Table 5, both materials exhibited enhanced adsorption performance, outperforming most of previously reported adsorbents. These findings underscore the promise of MgO-1 and MgO-2 as efficient and competitive materials for fluoride removal from contaminated wastewater.

Table 5.

Comparison of the maximum adsorption capacities for fluoride onto MgO-1 and MgO-2 with several other adsorbents including MgO-based composites.

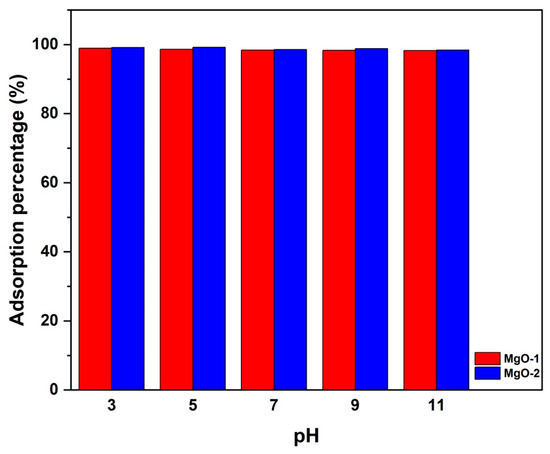

2.8. Effect of Solution Chemistry

The chemistry of the solution affects the chemical properties of both the adsorbent and the adsorbate, thereby impacting the overall sorption process. In this study, we focused on solution pH and background ions as key factors influencing fluoride removal near neutral pH. Previous research has shown that fluoride removal by MgO primarily occurs through specific interactions, such as the following [58,67]:

≡Mg-(OH)2 + 2F− → Mg-F2 + 2OH−

At high pH levels, the excess OH− ions tend to compete with F− ions for available adsorption sites, leading to a reduction in fluoride uptake. Since the pKa of HF is 3.18, fluoride ions in acidic conditions gradually convert into neutral species like HF and H2F2 [68], which are less likely to be adsorbed onto MgO. Consequently, a solution pH close to neutral is the most favorable for fluoride adsorption by MgO. The effect of pH on fluoride adsorption was examined over the pH range 3–11 for both MgO-1 and MgO-2 (Figure 10). The results show that the adsorption efficiency remains above 98% across the entire range, indicating that fluoride removal is only slightly affected by pH under the tested conditions. A small decline at pH 11 can be attributed to competition between hydroxide ions and fluoride ions for surface sites. The nearly constant adsorption efficiency between pH = 3 and pH = 9 can be explained by the amphoteric behavior of MgO surfaces. According to previous reports [69,70], the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of MgO lies between 11 and 12, implying that the surface remains positively charged at neutral pH. Consequently, electrostatic attraction between the positively charged MgO surface and fluoride anions (F−) plays a key role in the adsorption mechanism, together with surface complexation involving Mg2+ sites.

Figure 10.

Effect of solution pH on fluoride adsorption efficiency of MgO- and MgO-. Experimental conditions: initial fluoride concentration = 10 mg/L, adsorbent dose = 50 mg, contact time = 24 h, temperature = 25 °C.

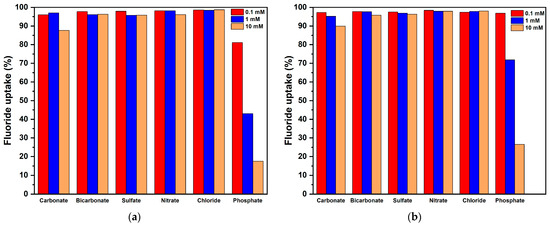

2.8.1. Effect of Coexisting Anions

Groundwater and industrial wastewater typically contain a variety of coexisting anions, such as nitrate, chloride, carbonate, bicarbonate, sulfate, and phosphate, which are commonly present in fluoride-contaminated water systems [71]. The influence of coexisting anions on the fluoride adsorption performance of MgO-1 and MgO-2 was investigated at approximately neutral pH to replicate the conditions commonly found in natural waters. Although the ionic strength of the solutions was not strictly controlled, this experimental approach provides a more realistic representation of the competitive adsorption environment typically encountered in groundwater and wastewater systems. The results are presented in Figure 11. As shown, the fluoride adsorption efficiency of both adsorbents was only slightly affected by the presence of the monovalent anions (Cl−, NO3−, and HCO3−) and the divalent anion (SO42−). When the concentration of these four competing ions was maintained at 10 mM, the fluoride removal capacity decreased by only about 4%. In contrast, at the same concentration, the presence of carbonate ions (CO32−) caused a more noticeable decline in performance, resulting in an approximately 12% reduction in adsorption capacity. While HCO3− is dominant near pH 8.3, its presence at neutral pH still allows limited competition with fluoride for adsorption sites through equilibrium with H2CO3 and CO32−. These results agree with previous reports indicating that divalent and amphoteric anions can partially suppress fluoride adsorption on metal oxides by occupying surface-active centers [72,73]. Overall, even in the presence of a high concentration of coexisting anions, both MgO-1 and MgO-2 demonstrated strong selectivity and remarkable adsorption stability toward fluoride removal. The preferential sorption of fluoride can be interpreted using the hard and soft acids and bases (HSAB) theory. In this system, MgO functions as a Lewis hard acid, while fluoride and other competing anions behave as Lewis hard bases. Among these anions, fluoride is classified as the hardest, which leads to its strongest interaction with MgO. As a result, MgO-1 and MgO-2 exhibit a strong affinity for fluoride ions.

Figure 11.

Effects of different concentrations (0.1, 1, and 10 mM) of interfering ions on the adsorption capacity (the initial F− concentration was constant, i.e., 10 mg/L) of: (a) MgO-1; (b) MgO-2.

However, high-valence anions exerted a negative influence on the defluorination performance of the MgO-based adsorbents. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that anions possessing a greater negative charge density exhibit a stronger electrostatic and ion-exchange interaction with the positively charged surface sites of MgO-1 and MgO-2. Among the competing species, phosphate ions showed the most pronounced interference and competitive adsorption toward fluoride, following the order: phosphate > carbonate > sulfate bicarbonate > chloride nitrate. The stronger competitive effect of the trivalent PO43− compared with CO32− is explained by its higher Gibbs free energy of hydration (−2765 kJ mol−1 for PO43− vs. −1315 kJ mol−1 for CO32−) [74,75].

2.8.2. Water Hardness

The water hardness of the samples used in the equilibrium tests (with fluoride concentrations of 30 and 300 mg/L) was measured for both types of nanoparticles (MgO-1 and MgO-2). A similar analysis was also conducted on a drinking water sample prior to assessing the fluoride removal performance of the synthesized magnesium oxides.

As shown in Table 6, the results indicate that the use of magnesium oxides does not contribute to water hardness during the adsorption process. Since deionized water was used, the only potential source of dissolved minerals is the magnesium oxide itself. However, due to its limited solubility, the resulting magnesium ion concentrations after reaching equilibrium are low. Additionally, the presence of these ions does not affect the fluoride adsorption process.

Table 6.

Water hardness results in water samples from equilibrium tests at fluoride ion concentrations of 30 and 300 mg/L.

Considering the low solubility of magnesium oxide (Ksp = 1.3 × 10−11, pKsp ≈ –10.89 at 25 °C) [76] and magnesium fluoride (Ksp = 6.6 × 10−9, pKsp ≈ –8.18 at 25 °C) [77], the release of Mg2+ ions into the aqueous phase is minimal under neutral pH conditions. Consequently, the fluoride removal process is mainly governed by surface adsorption and the formation of Mg–F surface complexes rather than bulk precipitation of MgF2(s). This conclusion is further supported by EDS analysis, which revealed homogeneous fluorine distribution over the MgO surface without distinct secondary crystalline phases.

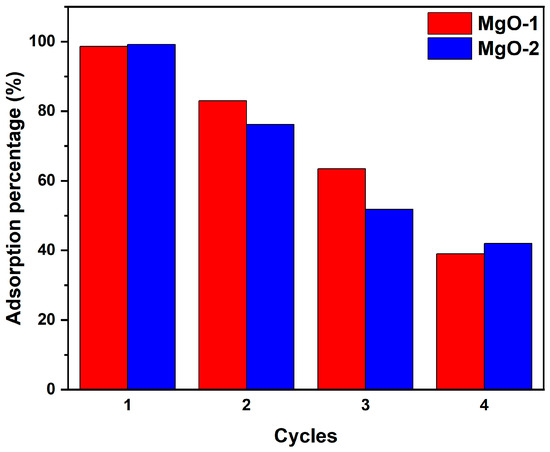

2.8.3. Reusability and Regeneration Performance

The regeneration performance of the synthesized MgO nanoparticles was evaluated through four consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles using 0.01 M NaOH as the regenerant (Figure 12). Both MgO-1 and MgO-2 maintained high fluoride removal efficiency during the first two cycles, with only moderate decreases thereafter. Specifically, MgO-1 retained 83% and MgO-2 retained 76% of their initial adsorption efficiency after the second cycle, indicating that the desorption treatment effectively reactivated the surface hydroxyl groups responsible for fluoride binding.

Figure 12.

Reusability performance of MgO-1 and MgO-2 nanoparticles over four consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles using 0.01 M NaOH as the regenerating agent.

A more pronounced decline was observed in the third and fourth cycles, where the efficiency dropped to 63.5% and 39% for MgO-1, and 51.8% and 42% for MgO-2, respectively. This gradual reduction can be attributed to partial surface saturation, structural relaxation, and loss of active sites during repeated washing and filtration. Nevertheless, both adsorbents demonstrated stable fluoride uptake over multiple cycles without complete deactivation, suggesting that the adsorption process is largely reversible and dominated by surface hydroxyl exchange (Mg–OH + F− ⇌ Mg–F + OH−) rather than irreversible MgF2 precipitation. These results confirm that MgO nanoparticles exhibit notable reusability under mild alkaline regeneration conditions, supporting their potential applicability in repeated water defluoridation operations with simple chemical regeneration protocols.

2.8.4. Studies in Drinking Water

The adsorbents MgO-1 and MgO-2 were evaluated using a tap water sample collected from the Chemical Sciences Laboratory at the Centro Universitario de los Lagos, Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico. A dose of 50 mg of each adsorbent was added to 50 mL of water containing an initial fluoride concentration of 2.11 mg/L, a pH of 8.5, and a hardness of 20.13 mg/L as CaCO3. The samples were subjected to agitation for 24 h, as determined by the adsorption kinetics, after which the solid and liquid phases were separated via centrifugation. The fluoride concentration in the supernatant was subsequently measured using the ion-selective electrode method. For both adsorbents, a reduction in fluoride concentration below the permissible limit (Table 7) was observed at a dosage of 1.0 g/L.

Table 7.

Fluoride removal with magnesium nanoparticles in drinking water.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid monohydrate (DCTA), glacial acetic acid, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and sodium chloride (NaCl) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received without further purification. Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2·6H2O), sodium fluoride (NaF), disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) and Eriochrome Black T were supplied by Merck S.A. de C.V. (Naucalpan de Juárez, Estado de México, Mexico). Solvents, salts, and other reagents were of analytical grade and used as received without additional purification. All solutions were prepared using deionized water.

3.1.1. Synthesis of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles MgO-1 and MgO-2

In an Erlenmeyer flask, 5.36 g (26.36 mmol) of MgCl2·6H2O was dissolved in 50 mL of DMF. The mixture was magnetically stirred until complete dissolution and heated to 70 °C. Subsequently, 24 mL of the precipitating agent: ammonium hydroxide at 28% v/v (for MgO-1) or ammonium carbonate at 10% w/v (for MgO-2) was added, and the suspension was stirred for 15 min at the same temperature. The resulting precipitate was aged for 24 h. The solid was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 min, washed three times with ethanol (centrifuging after each wash), and then dried at 110 °C for 24 h. Afterwards, the dried solid was ground with a mortar to obtain a fine powder and placed in a crucible for calcination in a muffle furnace at 800 °C for 6 h.

3.1.2. Preparation of TISAB II (Total Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer)

TISAB was used as a buffering solution to adjust the total ionic strength according to the Mexican Official Standard NOM-201-SSA1-2002. It was prepared by placing 500 mL of deionized water in a 1.0 L beaker, followed by the addition of 57 mL of glacial acetic acid, 58 g of NaCl, and 4.0 g of DCTA. The mixture was stirred until complete dissolution. The pH was then adjusted to between 5.0 and 5.5 by the slow addition of 6.0 N NaOH under continuous stirring. Finally, the volume was made up to 1.0 L in a volumetric flask.

3.2. Characterization

Infrared spectroscopic measurements were performed on a Frontier FTIR/FIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA; DTGS detector; KBr beamsplitter for mid-IR and aluminum grid/polypropylene beamsplitter for far-IR), using attenuated total reflection (ATR) or KBr disc technique.

The XRD patterns were recorded from 10° to 80° on a PANalytical X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Model Empyrean, Worcestershire, UK) with monochromatized Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Crystallite sizes (DC) were calculated from the line broadening of the X-ray diffraction peaks, applying the Debye–Scherrer Equation (7) [78,79],

where β is the breadth of the observed diffraction line at its half-intensity maximum (FWHM), k is the so-called shape factor, which usually takes a value of about 0.9, λ is the wavelength of X-ray source used in XRD and θ is the angle of reflection.

Thermal analyses were carried out using TG/DSC Q20TA/Q600-TA Instruments thermal analyzer (New Castle, DE, USA) in a dry air atmosphere (flow rate of 20 mL min−1, ambient pressure, heating rate 10 °C min−1 with a temperature range from 25 to 800 °C) using approximately 15 mg of compounds.

Morphological and elemental characterization was conducted using a JEOL JSM-7800F scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector (X-Max 80, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Powdered samples were mounted on graphite adhesive tape, and micrographs were captured under an accelerating voltage of 1 kV. The open-source software ImageJ (version 1.54g) was employed for quantitative image analysis to determine the average particle size of the MgO nanoparticles, based on measurements of at least 200 particles along their longest dimension.

The surface area, pore diameter, and pore volume of the synthesized nanocomposites were determined using nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms obtained from a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analyzer (Micromeritics TriStar II Plus, Norcross, GA, USA). The adsorption–desorption curves were utilized to calculate the specific surface area and textural parameters of the materials.

3.3. Adsorption Studies

Batch adsorption experiments were conducted to evaluate the equilibrium and kinetic behavior of fluoride adsorption onto MgO-1 and MgO-2 materials.

A stock fluoride solution (1000 mg/L) was prepared by dissolving 2.21 g of NaF (previously dried at 105 °C for one hour and cooled in a desiccator) in deionized water. The solution was diluted to one liter and stored in polyethylene bottles. Working solutions with concentrations ranging from 10 to 300 mg/L were prepared by dilution prior to use. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Adsorption tests were carried out in polypropylene Erlenmeyer flasks using a reaction volume of 30 mL. Experimental parameters such as initial fluoride concentration and contact time were varied or held constant depending on the study objective. After the agitation period, samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm, and the residual fluoride concentration was measured using an ion-selective electrode (HI98402 Fluoride Meter, Hanna Instruments, Padua, Italia), mixing the supernatant with TISAB II in a 1:1 volume ratio. Samples and standards were placed in 100 mL polyethylene beakers and continuously stirred with a magnetic stirrer during analysis. The equilibrium fluoride adsorption capacity qe (mg/g) was calculated using the following equation:

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium fluoride concentrations (mg/L), m is the mass of the adsorbent (g) and V is the solution volume (L).

3.3.1. Adsorption Kinetics

To evaluate the fluoride adsorption rate onto MgO-1 and MgO-2 nanoparticles and to determine the minimum contact time required to reach equilibrium at neutral pH and 25 °C, batch kinetic experiments were performed using various contact times. For each test, 50.0 mg of adsorbent was added to 30 mL of fluoride solution with a concentration of 10.0 mg/L. The suspensions were agitated for 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 24, 48, and 72 h. The amount of fluoride adsorbed at a given time t, denoted qt (mg/g), was calculated as follows:

where Ct (mg/L) represents the fluoride concentration at time t.

3.3.2. Adsorption Isotherms

Equilibrium adsorption studies were conducted to obtain the adsorption isotherms. A mass of 50 mg of adsorbent was mixed with 30 mL of fluoride solutions with varying concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg/L). These suspensions were agitated at a pH of approximately 6.5–7.0 and at 25 °C for 24 h, as defined by the adsorption kinetics study. Afterward, the samples were centrifuged, and the fluoride concentration was measured using the ion-selective electrode method.

3.3.3. Effect of Coexisting Anions

The influence of coexisting anions (phosphate, nitrate, chloride, carbonate, bicarbonate, and sulfate) on fluoride adsorption was assessed using batch experiments. Each test used a fixed adsorbent dose of 1.0 g/L and an initial fluoride concentration of 10.0 mg/L at a pH of approximately 6.5–7.0. Coexisting anions were added at concentrations of 0.1, 1.0, and 10 mM. The mixed suspensions were agitated at 40 rpm for 24 h at 25 °C.

3.4. Determination of Total Water Hardness

Water hardness was determined using the EDTA titration method. A standard EDTA solution was prepared and standardized by dissolving 4 g of disodium EDTA and 0.1 g of MgCl2·6H2O in 400 mL of deionized water, and then the volume was brought to 1 L. A calcium carbonate (CaCO3) standard solution was prepared by dissolving 0.4 g of CaCO3 (previously dried at 100 °C) in 100 mL of deionized water, followed by the gradual addition of 1:1 HCl until effervescence ceased and the solution cleared. The volume was adjusted to 500 mL with deionized water. Additionally, a buffer solution of ammonium-ammonium chloride was prepared by dissolving 6.75 g of NH4Cl in 57 mL of concentrated ammonia and diluting to 100 mL.

For standardization, 50 mL of CaCl2 standard solution was mixed in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask with 5 mL of buffer solution and 5 drops of Eriochrome Black T indicator. The mixture was titrated with the EDTA solution until the color changed from wine red to pure blue. The molarity of the EDTA solution was subsequently calculated.

To determine the total hardness of tap water and adsorption test samples, 50 mL of each sample was pipetted into a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. Then, 1 mL of buffer solution and 5 drops of indicator were added, followed by titration with the standardized EDTA solution until the color changed. Each measurement was performed in triplicate [80].

4. Conclusions

MgO nanoparticles synthesized via co-precipitation using different precipitating agents exhibited distinct morphological and adsorption characteristics, with MgO-1 outperforming MgO-2 in fluoride removal efficiency due to its smaller particle size and higher surface area. BET analysis confirmed both materials possessed mesoporous textures, with MgO-1 showing a slightly greater specific surface area that correlates with its enhanced adsorption capacity. The superior adsorption capacity of MgO-1 (117.6 mg/g) compared to MgO-2 (94.5 mg/g) was confirmed through isotherm and kinetic modeling, which revealed heterogeneous and exothermic fluoride–surface interactions, following pseudo-second-order and pseudo-first-order kinetics, respectively. The adsorption efficiency remained nearly constant from pH 3 to 9, indicating strong electrostatic attraction between fluoride ions and the positively charged MgO surface under near-neutral conditions. Both materials demonstrated strong fluoride selectivity even in the presence of common coexisting anions, and effectively treated real tap water samples, reducing fluoride concentrations below permissible limits without contributing to water hardness. These results position MgO nanoparticles as cost-effective, environmentally benign, and technically viable adsorbents for fluoride remediation in drinking water, with clear potential for large-scale application in regions facing chronic fluoride contamination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/inorganics13110370/s1, Figure S1: EDS spectrum of MgO-1; Figure S2: EDX mapping results of MgO-1; Figure S3: EDS spectrum of MgO-2; Figure S4: EDX mapping results of MgO-2; Figure S5: EDS spectrum of MgO-1 F; Figure S6: EDX mapping results of MgO-1 F; Figure S7: EDS spectrum of MgO-2 F; Figure S8: EDX mapping results of MgO-2 F.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.-G., J.A.P.-T. and R.P.; methodology, R.C.-G., J.A.P.-T., D.R.-d.-A. and R.P.; validation, R.C.-G. and J.A.P.-T.; formal analysis, R.C.-G. and J.A.P.-T.; investigation, R.C.-G. and J.A.P.-T.; resources, R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.-G. and J.A.P.-T.; writing—review and editing, Q.E.S.-A., D.R.-d.-A., E.G.-A., P.E.C.-A. and R.P.; visualization, R.C.-G., D.R.-d.-A., J.A.P.-T. and R.P.; supervision, J.A.P.-T. and R.P.; project administration, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Materials Characterization Laboratory, Maria-Christian Albor (CIO) for her technical assistance in the SEM and EDS measurements, and Brenda Mata Ortega (Chemical Sciences Laboratory, Universidad de Guadalajara) for the FTIR measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, P.; Xia, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Song, S. Simultaneous Sorption of Arsenate and Fluoride on Calcined Mg-Fe-La Hydrotalcite-Like Compound from Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16287–16297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Berg, M.; Winkel, L.; Hug, S.J.; Hoehn, E.; Yang, H.; Johnson, C.A. Statistical Modeling of Global Geogenic Fluoride Contamination in Groundwaters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3662–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawell, J.K.; Bailey, K. Fluoride in Drinking-Water; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Bai, P.; Li, W. Preparation of a Novel Magnesium Oxide Nanofilm of Honeycomb-Like Structure and Investigation of Its Properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 303, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Nakamura, A.; Niinae, M.; Nakata, H.; Fujii, H.; Tasaka, Y. Immobilization of Fluoride in Artificially Contaminated Kaolinite by the Addition of Commercial-Grade Magnesium Oxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 233, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Sheng, L.; Wu, T.; Huang, L.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Research Progress on the Application of Carbon-Based Composites in Capacitive Deionization Technology. Desalination 2025, 593, 118197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q. High-Efficiency Fluoride Removal Using Hierarchical Flower-Like Magnesium Oxide: Adsorption Characteristics and Mechanistic Insights. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 17268–17276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K. Layered Magnesium Oxide for Efficient Removal of Fluoride from Groundwater. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L. Deep Removal of Fluoride by Highly Activated Magnesium Oxide. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, F.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. Comparison of Fluorine Removal Performance and Mechanism of Spheroidal Magnesium Oxide before and after Lanthanum Modification. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 80477–80490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Lin, J.; Tao, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; He, F. Enhanced Fluoride Removal from Water by Nanoporous Biochar-Supported Magnesium Oxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 9988–9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, J. Removing Fluoride from Water by Nanostructured Magnesia-Impregnated Activated Carbon. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, H.; Morimoto, K.; Saito, T.; Hara, J. Simultaneous Removal of Arsenate and Fluoride Using Magnesium-Based Adsorbents. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castillo, J.G.; Macedo-Miranda, G.; Martínez-Gallegos, S.; Ordoñez-Regíl, E.; Álvarez-García, S.; Illescas-Martínez, J. Fluoride Removal Using a MgFe Hydrotalcite and a MgFe Oxide. MRS Adv. 2020, 5, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Pan, A.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, C.; Fu, G.; Peng, C.; Zhu, J.; Wan, X. Hierarchical Camellia-Like Metal–Organic Frameworks via a Bimetal Competitive Coordination Combined with Alkaline-Assisted Strategy for Boosting Selective Fluoride Removal from Brick Tea. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 642, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, J.P.; Liu, K.J.; Feng, N.X.; Di, Y.Z. Surface Area Control of Nanocomposites Mg(OH)2/Graphene Using a Cathodic Electrodeposition Process: High Adsorption Capability of Methyl Orange. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 88315–88320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Saini, R.; Bhaduri, A. Facile Synthesis of MgO Nanoparticles for Effective Degradation of Organic Dyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 71439–71453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Zou, L.Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Li, G.M. Controlled Synthesis and Enhanced Bacteriostatic Activity of Mg(OH)2/Ag Nanocomposite. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilango, K.N.; Nguyen, H.; Alzeer, M.; Winnefeld, F.; Kinnunen, P. Stabilization of Nesquehonite for Application in Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat-Torres, P.; Winnefeld, F.; Lothenbach, B. Impact of Nesquehonite on Hydration and Strength of MgO-Based Cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 189, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayakina, N.V.; Ugapeva, S.S.; Oleinikov, O.B. Nesquehonite from the Kimberlite Pipe Obnazhennaya: Thermal Analysis and Infrared Spectroscopy. In Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnesium Hydroxide by Batch Reaction Crystallization. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2011, 5, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, C.Y.; Tai, C.T.; Chang, M.H.; Liu, H.S. Synthesis of Magnesium Hydroxide and Oxide Nanoparticles Using a Spinning Disk Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 5536–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrist, C.; Mathieu, J.-P.; Vogels, C.; Rulmont, A.; Cloots, R. Morphological Study of Magnesium Hydroxide Nanoparticles Precipitated in Dilute Aqueous Solution. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 249, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, G.; Tang, G.; Jia, C.; Zhang, H. Microbial Synergistic Active Magnesium Oxide Solidification of Water-Based Drilling Cuttings and Analysis of Its Durability Strength Loss Mechanism. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 11968–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Hao, Q.; Ju, Z.; Xu, L.; Qian, Y. Synthesis of MgCO3 Microcrystals at 160 °C Starting from Various Magnesium Sources. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 1401–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashab, B. Barringtonite—A New Hydrous Magnesium Carbonate from Barrington Tops, New South Wales, Australia. Mineral. Mag. 1965, 34, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Saddiq, A.A.; Alruhaili, M.H.; Saied, E.; Sharaf, M.H.; Tarabulsi, M.K.; Al Jaouni, S.K. Synthesis of Novel MgO-ZnO Nanocomposite Using Pluchea indica Leaf Extract and Study of Their Biological Activities. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Efficient Removal of Fluoride by Hierarchical MgO Microspheres: Performance and Mechanism Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 357, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghavi, R.J.; Upadhyay, S.C.; Kumar, A. Management of Solid Waste Marble Powder: Improving Quality of Sodium Chloride Obtained from Sulphate-Rich Lake/Subsoil Brines with Simultaneous Recovery of High-Purity Gypsum and Magnesium Carbonate Hydrate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 40068–40078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Zou, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Fan, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, M. In-Situ Hydrothermal Crystallization Mg(OH)2 Films on Magnesium Alloy AZ91 and Their Corrosion Resistance Properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 143, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Palmer, S.J. Infrared and Infrared Emission Spectroscopy of Nesquehonite Mg(OH)(HCO3)·2H2O—Implications for the Formula of Nesquehonite. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincke, C.; Schmidt, H.; Buth, G.; Voigt, W. Crystal Structure and Characterization of Magnesium Carbonate Chloride Heptahydrate. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2020, 76, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Liang, X. Temperature- and pH-Dependent Morphology and FT-IR Analysis of Magnesium Carbonate Hydrates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 12969–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazmi, F.; Alnowaiser, F.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Aly, M.; Al-Tuwirqi, R.M.; El-Tantawy, F. A New Large-Scale Synthesis of Magnesium Oxide Nanowires: Structural and Antibacterial Properties. Superlattices Microstruct. 2012, 52, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, P. Steering Reduction and Decomposition of Peroxide Compounds by Interface Interactions between MgO Thin Film and Transition-Metal Support. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 459, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, R.; Bozzi, C.; Dei, L.; Gabbiani, C.; Ninham, B.W.; Baglioni, P. Nanoparticles of Mg(OH)2: Synthesis and Application to Paper Conservation. Langmuir 2005, 21, 8495–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Kang, Y.; Chae, S.; Kim, C. Forced Mineral Carbonation of MgO Nanoparticles Synthesized by Aerosol Methods at Room Temperature. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Iqbal, A. Synthesis of 2D Magnesium Oxide Nanosheets: A Potential Material for Phosphate Removal. Glob. Challenges 2018, 2, 1800056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, J.; Sisi, A.J.; Hadipoor, M.; Khataee, A. State of the Art on the Ultrasonic-Assisted Removal of Environmental Pollutants Using Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, D.; Sarva, V.R.; Prasad, S.V.; Arunachalam, J.; Parameswaran, P.; Ghosh, N.N. Synthesis of MgO Nanoparticle Loaded Mesoporous Al2O3 and Its Defluoridation Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 329, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. Zur Theorie der Sogenannten Adsorption Geloster Stoffe. Kungl. Sven. Vetenskapsakad. Handl. 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-Second Order Model for Sorption Processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; You, S.J.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Chao, H.P. Mistakes and Inconsistencies Regarding Adsorption of Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2017, 120, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.J.; Gan, Q.; Matthews, R.; Johnson, P.A. Comparison of Optimised Isotherm Models for Basic Dye Adsorption by Kudzu. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 88, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, F.; Akbar, J.; Iqbal, S.; Noreen, S.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Study of Isothermal, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Parameters for Adsorption of Cadmium: An Overview of Linear and Nonlinear Approach and Error Analysis. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2018, 2018, 3463724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wang, H.; Sun, B.; Deng, P.; Hou, S.; Yu, Y. Adsorption of Fluoride from Aqueous Solution by Magnesia-Amended Silicon Dioxide Granules. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Cui, H.; Pang, J.; Sun, L.; An, H.; Zhai, J. Adsorption of Fluoride from Aqueous Solution on Magnesia-Loaded Fly Ash Cenospheres. Desalination 2011, 272, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Li, B.; Song, J.; Li, D.; Yang, J.; Zhan, W.; Liu, D. Defluoridation of Water Using Calcined Magnesia/Pullulan Composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.R.; Umlong, I.M.; Raul, P.K.; Das, B.; Banerjee, S.; Singh, L. Defluoridation of Water Using Nano-Magnesium Oxide. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2014, 9, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minju, N.; Venkat Swaroop, K.; Haribabu, K.; Sivasubramanian, V.; Senthil Kumar, P. Removal of Fluoride from Aqueous Media by Magnesium Oxide-Coated Nanoparticles. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 53, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, S.; Sasaki, K.; Hirajima, T. Effect of Calcination Temperature on Mg-Al Bimetallic Oxides as Sorbents for the Removal of Fluoride in Aqueous Solutions. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.X.; Xu, D.; Li, X.Q.; Liu, W.C.; Jia, Y. Excellent Fluoride Removal Properties of Porous Hollow MgO Microspheres. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 5445–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoja, N.A.; Chen, S.; Drewes, J.E.; Helmreich, B. Characterization of Granular Matrix Supported Nano Magnesium Oxide as an Adsorbent for Defluoridation of Groundwater. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, K.-S.; Kong, L.-T.; Sun, B.; Shen, W.; Meng, F.-L.; Liu, J.-H. Effective Removal of Fluoride by Porous MgO Nanoplates and Its Adsorption Mechanism. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 675, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Ha, J.W.; Sohn, E.H.; Park, I.J.; Lee, S.B. Synthesis of Pillar and Microsphere-Like Magnesium Oxide Particles and Their Fluoride Adsorption Performance in Aqueous Solutions. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 2738–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullick, A.; Neogi, S. Ultrasound Assisted Synthesis of Mg-Mn-Zr Impregnated Activated Carbon for Effective Fluoride Adsorption from Water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 50, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, A.; Govindaraj, D.; Rajan, M. Magnesium Oxide Entrapped Polypyrrole Hybrid Nanocomposite as an Efficient Selective Scavenger for Fluoride Ion in Drinking Water. Emergent Mater. 2018, 1, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, L.; Yue, X.; Xu, C.; Lu, X. Removal of Fluoride and Hardness by Layered Double Hydroxides: Property and Mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Jin, J.; Fu, J.; Yang, M.; Li, F. Anchoring Al- and/or Mg-Oxides to Magnetic Biochars for Co-Uptake of Arsenate and Fluoride from Water. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Panigrahi, G.K.; Dhal, J.P.; Sahoo, J.K.; Behera, A.K.; Panda, P.C.; Patel, P.; Mund, S.K.; Muduli, S.M.; Panda, L. Co-Axial Electrospun Hollow MgO Nanofibers for Efficient Removal of Fluoride Ions from Water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 652, 129877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Mondal, D.; Mandal, S.; Khatun, J.; Mukherjee, A.; Dhak, D. One-Pot Solution Combustion Synthesis of Porous Spherical-Shaped Magnesium Zinc Binary Oxide for Efficient Fluoride Removal and Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue and Congo Red Dye. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 81386–81402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Panda, B.; Mondal, D.; Khatun, J.; Dhak, P.; Dhak, D. 3D Flower-Like Zirconium Magnesium Oxide Nanocomposite for Efficient Fluoride Removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 119491–119505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaresahmadi, K.; Khodadoust, A.P.; Wescott, J. Defluoridation of Water Using Cu-Mg-Binary-Metal-Oxide-Coated Sand. Water 2024, 16, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Fukumoto, N.; Moriyama, S.; Hirajima, T. Sorption Characteristics of Fluoride onto Magnesium Oxide-Rich Phases Calcined at Different Temperatures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 191, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Phanlavong, P.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, T.; Qiu, H.; Peng, Q. Highly Efficient and Rapid Fluoride Scavenger Using an Acid/Base Tolerant Zirconium Phosphate Nanoflake: Behavior and Mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, R.; Medina, O.E.; Giraldo, L.J.; Cortés, F.B.; Franco, C.A. Development of Nanofluids for the Inhibition of Formation Damage Caused by Fines Migration: Effect of the Interaction of Quaternary Amine (CTAB) and MGO Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, N.M.; Zarzycki, P.; Wang, Z.; Rosso, K.M. pH-Dependent Reactivity of Water at MgO(100) and MgO(111) Surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 4343–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Ye, B.C. Efficient Removal of Fluoride from Aqueous Solutions Using 3D Flower-Like Hierarchical Zinc-Magnesium-Aluminum Ternary Oxide Microspheres. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuda-Stanić, M.; Ravančić, M.; Flanagan, A. A Review on Adsorption of Fluoride from Aqueous Solution. Materials 2014, 7, 6317–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahramanlioglu, M.; Kizilcikli, I.; Bicer, I.O. Adsorption of Fluoride from Aqueous Solution by Acid-Treated Spent Bleaching Earth. J. Fluorine Chem. 2002, 115, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca Fındık, B.; Jafari, M.; Song, L.F.; Li, Z.; Aviyente, V.; Merz, K.M. Binding of Phosphate Species to Ca2+ and Mg2+ in Aqueous Solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 4298–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Y. Thermodynamics of Solvation of Ions. Part 5.—Gibbs Free Energy of Hydration at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1991, 87, 2995–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmaier, M.; Metz, V.; Neck, V.; Müller, R.; Fanghänel, T. Solid–Liquid Equilibria of Mg(OH)2(cr) and Mg2(OH)3Cl·4H2O(cr) in the System Mg–Na–H–OH–Cl–H2O at 25 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booster, J.L.; Van Sandwijk, A.; Reuter, M.A. Thermodynamic Modelling of Magnesium Fluoride Precipitation in Concentrated Zinc Sulphate Environment. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Dadkhah, M.; Davar, F. Pure Cubic ZrO2 Nanoparticles by Thermolysis of a New Precursor. Polyhedron 2009, 28, 3005–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvie, R.C. The Occurrence of Metastable Tetragonal Zirconia as a Crystallite Size Effect. J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, J.D.; Noll, C.A. Total-Hardness Determination by Direct Colorimetric Titration. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1950, 42, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).