Robust Four-Wave Mixing and Double Second-Order Optomechanically Induced Transparency Sideband in a Hybrid Optomechanical System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

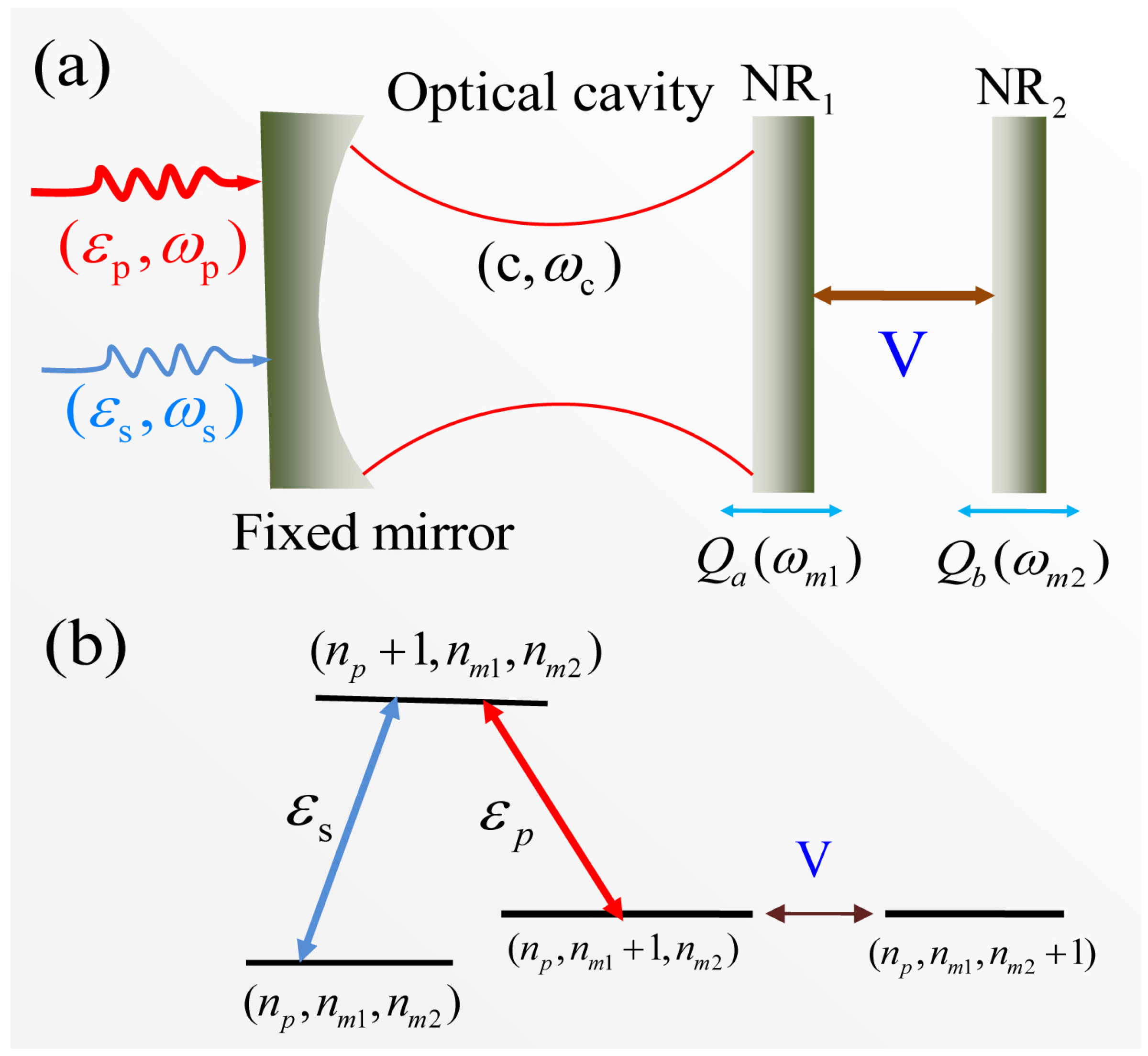

2. System and Method

3. Results and Discussion

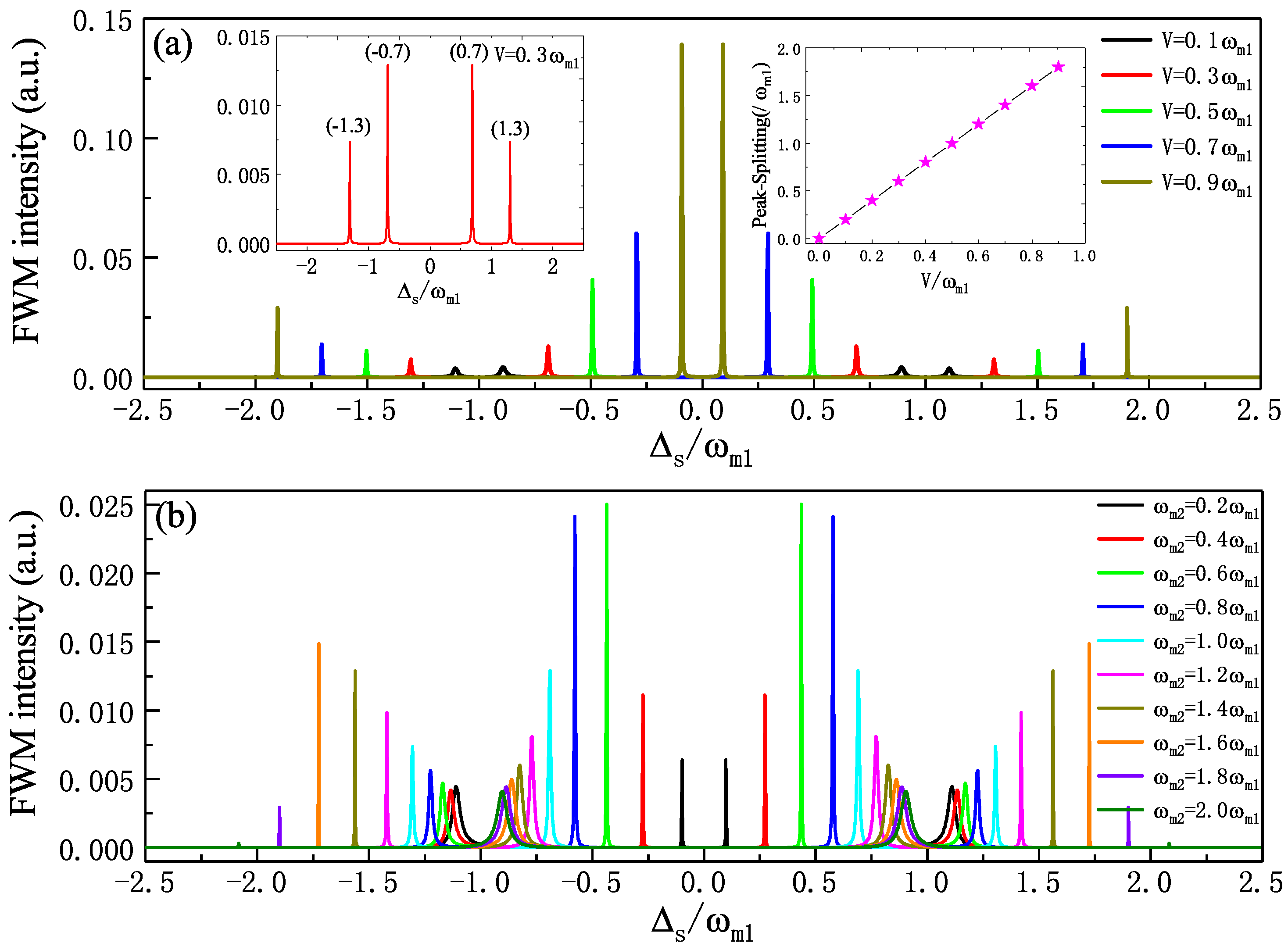

3.1. The FWM Process

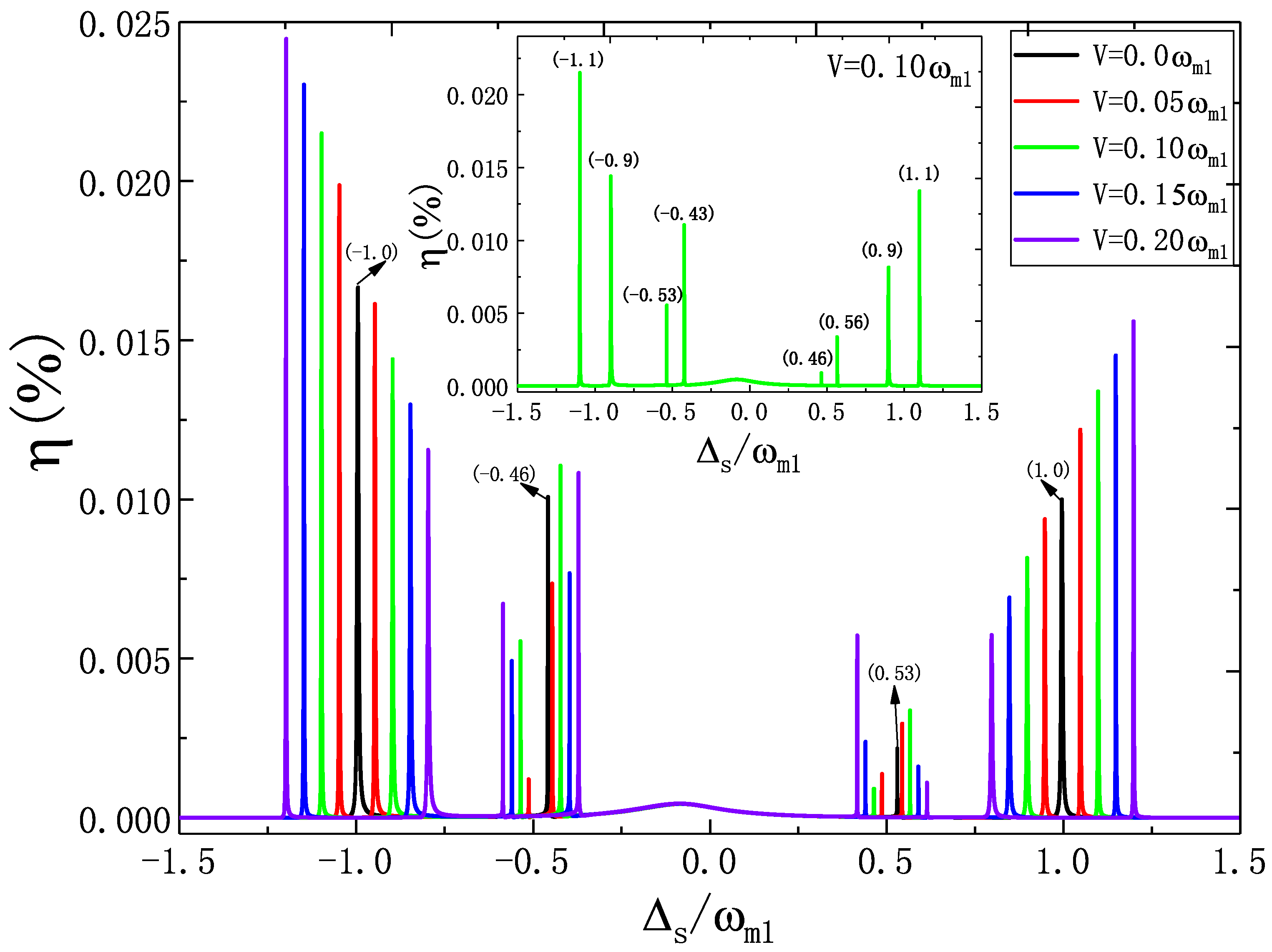

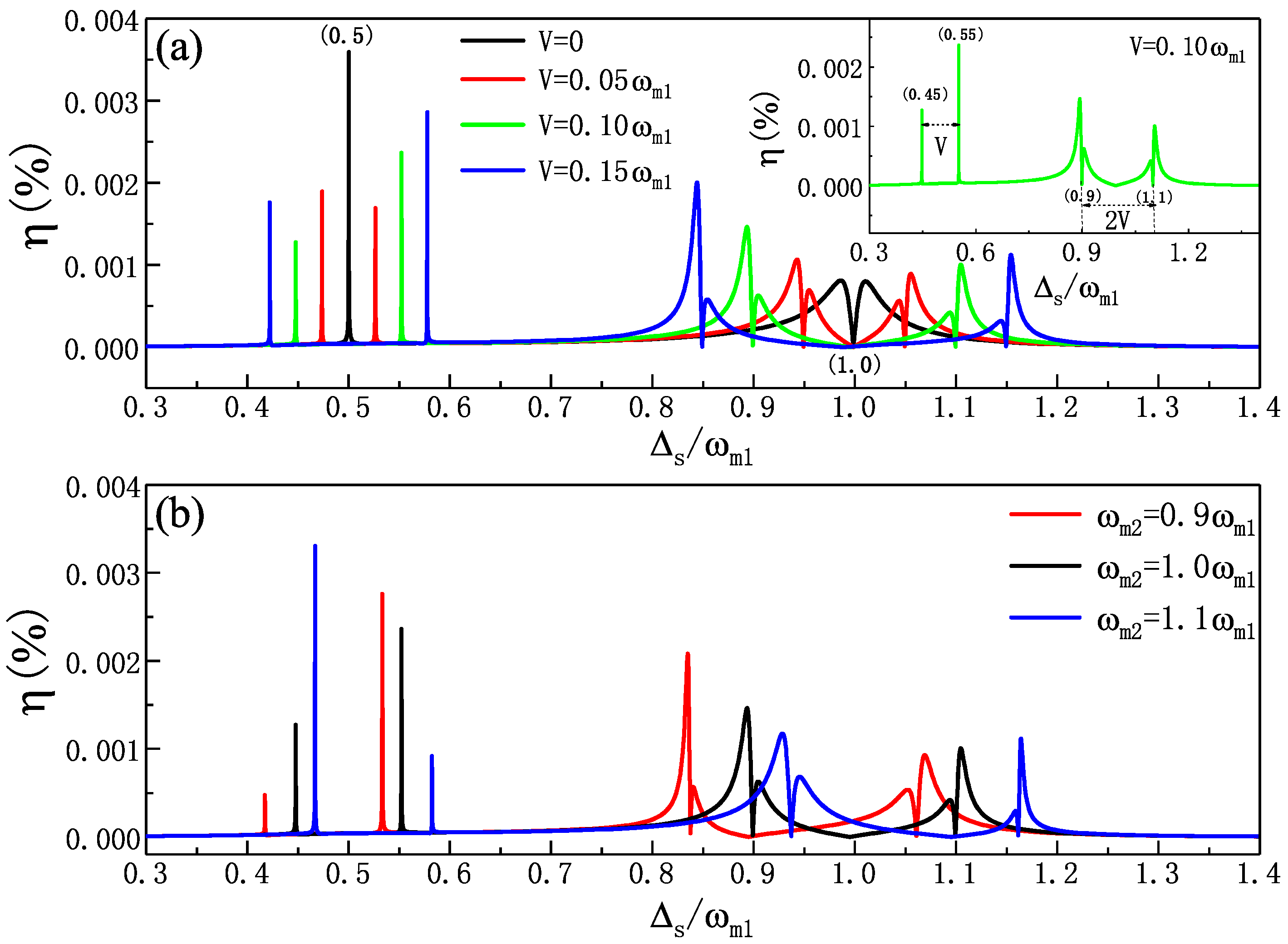

3.2. The SSG Process

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aspelmeyer, M.; Kippenberg, T.J.; Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, M. Applications of cavity optomechanics. App. Phys. Rev. 2014, 1, 031105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milestones: Photons. Available online: https://www.nature.com/milestones/milephotons/timeline.html (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Schliesser, A.; Riviere, R.; Anetsberger, G.; Arcizet, O.; Kippenberg, T.J. Resolved-sideband cooling of a micromechanical oscillator. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teufel, J.D.; Donner, T.; Li, D.; Harlow, J.W.; Allman, M.S.; Cicak, K.; Sirois, A.J.; Whittaker, J.D.; Lehnert, K.W.; Simmonds, R.W. Sideband cooling of micromechanical motion to the quantum ground state. Nature 2011, 475, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, J.; Alegre, T.P.M.; Safavi-Naeini, A.H.; Hill, J.T.; Krause, A.; Groblacher, S.; Aspelmeyer, M.; Painter, O. Laser cooling of a nanomechanical oscillator into its quantum ground state. Nature 2011, 478, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.-C.; Peng, P.; Zhi, Y.; Xiao, Y.-F. Cooling of macroscopic mechanical resonators in hybrid atomoptomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 033841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.-G.; Zou, F.; Hou, B.-P.; Xiao, Y.-F.; Liao, J.-Q. Simultaneous cooling of coupled mechanical resonators in cavity optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 023860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.J.; Zhu, K.D. All-optical mass sensing with coupled mechanical resonator systems. Phys. Rep. 2013, 525, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, K.D. Ultrasensitive nanomechanical mass sensor using hybrid opto-electromechanical systems. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 13773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliesser, A.; Arcizet, O.; Riviere, R.; Anetsberger, G.; Kippenberg, T.J. Resolved-sideband cooling and position measurement of a micromechanical oscillator close to the Heisenberg uncertainty limit. Nat. Phys. 2009, 5, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basiri-Esfahani, S.; Akram, U.; Milburn, G.J. Phonon number measurements using single photon opto-mechanics. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 085017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gavartin, E.; Verlot, P.; Kippenberg, T.J. A hybrid on-chip optomechanical transducer for ultrasensitive force measurements. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krause, A.G.; Winger, M.; Blasius, T.D.; Lin, Q.; Painter, O. A high-resolution microchip optomechanical accelerometer. Nat. Photon. 2012, 6, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schreppler, S.; Spethmann, N.; Brahms, N.; Botter, T.; Barrios, M.; Stamper-Kurn, D.M. Optically measuring force near the standard quantum limit. Science 2014, 344, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiong, H.; Si, L.G.; Wu, Y. Precision measurement of electrical charges in an optomechanical system beyond linearized dynamics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 171102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Catano-Lopez, S.B.; Sugawara, M.; Suzuki, S.; Abe, N.; Komori, K.; Michimura, Y.; Aso, Y.; Edamatsu, K. Demonstration of Displacement Sensing of a mg-Scale Pendulum for mm- and mg-Scale Gravity Measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.D.; Clerk, A.A. Using interference for high fidelity quantum state transfer in optomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 153603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L. Adiabatic state conversion and pulse transmission in optomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 153604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, L. Robust photon entanglement via quantum interference in optomechanical interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 233602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Clerk, A.A. Reservoir-engineered entanglement in optomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 253601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grudinin, I.S.; Lee, H.; Painter, O.; Vahala, K.J. Phonon laser action in a tunable two-level system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 083901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, B.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Pichler, K.; Krimer, D.O.; Zhao, G.; Nori, F.; Liu, Y.; Rotter, S.; Yang, L. A phonon laser operating at an exceptional point. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Lü, X.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Nori, F. PT-symmetric phonon laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 053604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lü, H.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Kuang, L.M.; Nori, F.; Jing, H. Exceptional points in random-defect phonon lasers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2017, 8, 044020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Safavi-Naeini, A.H.; Groeblacher, S.; Hill, J.T.; Chan, J.; Aspelmeyer, M.; Painter, O. Squeezed light from a silicon micromechanical resonator. Nature 2013, 500, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, G.S.; Huang, S.M. Strong mechanical squeezing and its detection. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 043844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manipatruni, S.; Robinson, J.T.; Lipson, M. Optical nonreciprocity in optomechanical structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 213903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.W.; Li, Y.; Chen, A.X.; Liu, Y.X. Nonreciprocal conversion between microwave and optical photons in electro-optomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 023827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, C.; Song, L.N.; Li, Y. Directional amplifier in an optomechanical system with optical gain. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 053812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lü, X.-Y.; Jing, H.; Ma, J.-Y.; Wu, Y. PT -symmetry-breaking chaos in optomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 253601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Mason, D.; Jiang, L.; Harris, J.G.E. Topological energy transfer in an optomechanical system with exceptional points. Nature 2016, 537, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, G.S.; Huang, S. Electromagnetically induced transparency in mechanical effects of light. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 041803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Li, B.-B.; Xiao, Y.-F. Electromagnetically induced transparency in optical microcavities. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.; Riviere, R.; Deleglise, S.; Gavartin, E.; Arcizet, O.; Schliesser, A.; Kippenberg, T.J. Optomechanically induced transparency. Science 2010, 330, 1520–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Safavi-Naeini, A.H.; Alegre, T.P.M.; Chan, J.; Eichenfield, M.; Winger, M.; Lin, Q.; Hill, J.T.; Chang, D.E.; Painter, O. Electromagnetically induced transparency and slow light with optomechanics. Nature 2011, 472, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teufel, J.D.; Li, D.; Allman, M.S.; Cicak, K.; Sirois, A.J.; Whittaker, J.D.; Simmonds, R.W. Circuit cavity electromechanics in the strong-coupling regime. Nature 2011, 471, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fan, L.; Fong, K.Y.; Poot, M.; Tang, H.X. Cascaded optical transparency in multimode-cavity optomechanical systems. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, J.; Fiore, V.; Wang, H. Optomechanically induced transparency and self-induced oscillations with Bogoliubov mechanical modes. Optica 2014, 1, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.Z.; Jing, H. Optomechanically induced transparency in a spinning resonator. Photonics Res. 2017, 5, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, H.X.; Cui, Y.S.; Li, X.W.; Chen, G.B.; Chen, B. Electromagnetically induced transparency and slow light in two-mode optomechanics. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, X.; Hocke, F.; Schliesser, A.; Marx, A.; Huebl, H.; Gross, R.; Kippenberg, T.J. Slowing, advancing and switching of microwave signals using circuit nanoelectromechanics. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiore, V.; Dong, C.; Kuzyk, M.C.; Wang, H. Optomechanical light storage in a silica microresonator. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 023812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.-J.; Hou, B.-C.; Yang, J.-Y. Controllable coherent optical response in a ring cavity optomechanical system. Phys. E 2021, 125, 114394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sete, E.A.; Eleuch, H. Controllable nonlinear effects in an optomechanical resonator containing a quantum well. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 043824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamoto, R.; Meystre, P. Optomechanics of a quantum-degenerate Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 063601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purdy, T.P.; Brooks, D.W.C.; Botter, T.; Brahms, N.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Stamper-Kurn, D.M. Tunable cavity optomechanics with ultracold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 133602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, D.; Wang, Z.H.; Ren, C.N.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.H. Duality and bistability in an optomechanical cavity coupled to a Rydberg superatom. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 91, 023813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Jin, D.Y.; Qiu, Y.; Lam, C.H.; You, J.Q. Cross-Kerr effect on an optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 023844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, S.; Agarwal, G.S. Normal-mode splitting and antibunching in Stokes and anti-Stokes processes in cavity optomechanics: Radiation-pressure-induced four-wave-mixing cavity optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 033830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, W.Z.; Wei, L.F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Phase-dependent optical response properties in an optomechanical system by coherently driving the mechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 91, 043843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.W.; Li, Y. Controllable optical output fields from an optomechanical system with mechanical driving. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 023855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.J.; Wu, H.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Li, X.C.; Sun, Y.J.; Peng, Y. Controllable Optical Bistability and Four-Wave Mixing in a Photonic-Molecule Optomechanics. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Si, L.G.; Zheng, A.S.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y. Higher-order sidebands in optomechanically induced transparency. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 013815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, H.; Brown, E.; Sterling, R. Nonlinear dynamics of an optomechanical system with a coherent mechanical pump: Second-order sideband generation. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 033823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiao, Y.; Lu, H.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Jing, H. Nonlinear optomechanics with gain and loss: Amplifying higher-order sideband and group delay. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 083034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Xiao, Q.; Wu, Y. Giant enhancement of optical high-order sideband generation and their control in a dimer of two cavities with gain and loss. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 063814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Si, L.-G.; Lu, X.-Y.; Wu, Y. Optomechanically induced sum sideband generation. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Fan, Y.-W.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y. Radiation pressure induced difference-sideband generation beyond linearized description. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 061108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Xiong, H.; Wu, Y. Coulomb-interaction-dependent effect of high-order sideband generation in an optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 033820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Si, L.-G.; Guo, L.-X.; Xiong, H.; Wu, Y. Tunable high-order-sideband generation and carrier-envelope-phase–dependent effects via microwave fields in hybrid electro-optomechanical systems. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 023805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.-F.; Lu, T.-X.; Jing, H. Optomechanical second-order sidebands and group delays in a Kerr resonator. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 013843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yellapragada, K.C.; Pramanik, N.; Singh, S.; Lakshmi, P.A. Optomechanical effects in a macroscopic hybrid system. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 053822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Shang, L.; Wang, X.-F.; Chen, J.-B.; Xue, H.-B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Atom-assisted second-order sideband generation in an optomechanical system with atom-cavity-resonator coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 063810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.-C.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhang, Z.-M. Tunable double optomechanically induced transparency in an optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 043825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.Q.; Ma, P.C.; Yao, C.M.; Feng, M. Precision measurement of the environmental temperature by tunable double optomechanically induced transparency with a squeezed field. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 91, 063827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.-C.; Qin, L.-G.; Jing, J.; Yan, T.-M.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.-Y. Microwave-controlled optical double optomechanically induced transparency in a hybrid piezo-optomechanical cavity system. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 013807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyd, R.W. Nonlinear Optics; Academic: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992; p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, C.W.; Zoller, P. Quantum Noise; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, H. Controllable four-wave mixing based on mechanical vibration in two-mode optomechanical systems. Europhys. Lett. 2013, 104, 34004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groblacher, S.; Hammerer, K.; Vanner, M.R.; Aspelmeyer, M. Observation of strong coupling between a micromechanical resonator and an optical cavity field. Nature 2009, 460, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, C.; Chen, B.; Zhu, K.D. Controllable nonlinear responses in a cavity electromechanical system. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2012, 29, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.W.; Chen, B.; Xing, L.L.; Chen, J.B.; Xue, H.B.; Guo, K.X. Controllable four-wave mixing based on quantum dot-cavity coupling system. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2021, 73, 055101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H. Robust Four-Wave Mixing and Double Second-Order Optomechanically Induced Transparency Sideband in a Hybrid Optomechanical System. Photonics 2021, 8, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8070234

Chen H. Robust Four-Wave Mixing and Double Second-Order Optomechanically Induced Transparency Sideband in a Hybrid Optomechanical System. Photonics. 2021; 8(7):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8070234

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huajun. 2021. "Robust Four-Wave Mixing and Double Second-Order Optomechanically Induced Transparency Sideband in a Hybrid Optomechanical System" Photonics 8, no. 7: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8070234

APA StyleChen, H. (2021). Robust Four-Wave Mixing and Double Second-Order Optomechanically Induced Transparency Sideband in a Hybrid Optomechanical System. Photonics, 8(7), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8070234