Abstract

A self-pulsing III-V/silicon laser is designed based on the Fano resonance between a bus-waveguide and a micro-ring resonator, partially covered by the graphene as a nonlinear saturable absorption component. The Fano reflector etched on the straight waveguide is used as one of the cavity mirrors in the coupling region to work with the graphene induced loss and nonlinearity to achieve pulsed lasing in GHz repetition frequency. The detailed lasing characteristics are studied numerically by using the rate equation and finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations. The results show that the CMOS compatible hybrid laser can generate picosecond pulses with repetition rate at 1~3.12 GHz, which increases linearly with the injection current.

1. Introduction

Along with the rapid development of chip-integrated light detection/ranging (LiDAR) [1,2], neuromorphic computation [3], and microwave photonics [4,5] in various scientific and industrial applications, the pulsed semiconductor lasers are the main focus to enable device miniaturization, low power consumption, and cost reduction. The generation of ultrashort pulses with high repetition rate has been realized with mode-locked laser diodes for the III-V type materials [6,7,8], but the passive waveguide loss on the III-V platform (3–4 dB/cm at 1550 nm) is larger than that of the silicon waveguide (0.7 dB/cm) [6,9], which limits the active-passive integration and device performance, such as the spectral linewidth, output power, etc. The III-V/Si hybrid pulsed laser [10,11,12,13] is, therefore, an alternative way, and ideally suited, for the integration with high-speed silicon modulators and germanium photodetectors to utilize the mature CMOS fabrication.

Actually, the semiconductor mode-locked laser diodes have been demonstrated on the III-V-on-silicon platform [9,14,15,16] to generate high-repetition-rate pulse-train signals in narrow linewidth and low phase-noise without external modulations [17]. The pulsed mode of the diodes is enabled by applying reverse bias on the saturable absorption (SA) region, where optimizations can be done for that region, as well as the longitudinal cavity, to overcome the change in refractive index under large negative bias [18].

The two-dimensional (2D) nano-materials with large third-order susceptibility can be used to achieve fast optical switching and pulsation without extra bias for the SA [19,20,21,22]. In this study, we investigate the electrically-pumped self-pulsing laser diode based on the heterogeneous III-V/Si platform, using the micro-ring partially covered by graphene as the SA region, and the Fano resonance effect between the micro-ring and the bus-waveguide to enable self-sustainable pulsing at high repetition rate with low absorption loss. The physical model of the laser, including the Fano mirror design and related mechanisms, are analyzed, respectively.

2. Device Structure and Design Optimization

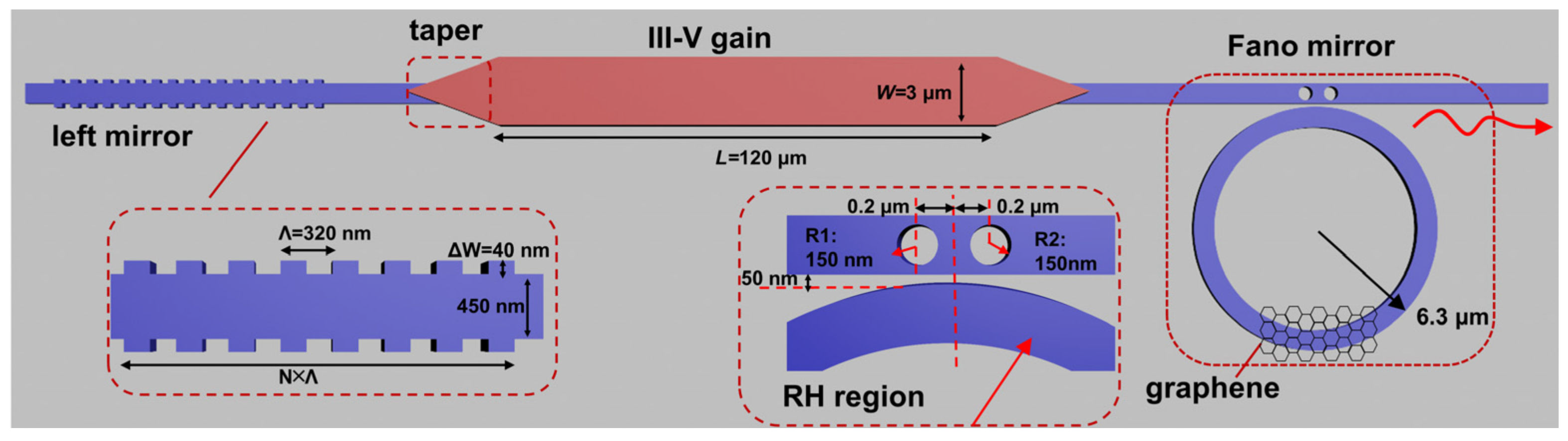

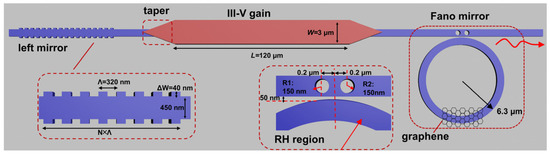

The device structure is schematically shown in Figure 1, where the Fano-mirror on the right-hand side is composed of reflection holes (RH) in the bus waveguide and a micro-ring covered by the graphene layer, to select appropriate resonance wavelength for the gigahertz repetition-rate output pulses. The left Bragg mirror is done by etching the surface gratings on the silicon waveguide to obtain high reflection facet. Tapers in-between the III-V gain region and the silicon waveguide are applied to couple light adiabatically with low propagation loss.

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the III-V/Si Fano laser, where RH represents the reflection holes etched on the bus waveguide.

Here, the Si layer thickness for the waveguide and micro-ring is standard 220 nm, with ridge widths of 450 nm. The outer/inner radius of the ring is 6.3/5.85 μm and is separated from the bus waveguide with a 50-nm lateral gap, as optimized by the FDTD calculations [23].

In order to improve the self-pulsed hybrid silicon laser performance, we can optimize the passive and active regions, correspondingly, which include the Fano mirror, Bragg mirror, tapered coupling region, and multiple quantum wells (MQW), as follows.

2.1. Fano Mirror

As a key component of the proposed laser structure, high slope-rate Fano mirror can be used at one end of the silicon waveguide to minimize the reflection peak linewidth for fast switching of the laser. Here, RH is etched in the coupling region of the waveguide near the micro-ring, such that output light from the active region could be scattered/coupled evanescently to the micro-ring with extra phase delay and modified coupling coefficients [24], to induce the Fano-type asymmetric reflection spectrum.

The reflectivity can be calculated either from the analytical formula [25,26] or numerical FDTD method, for use in the next-step laser simulations. As derived from the scattering theory [25] for the coupled micro-ring-waveguide system in the absence of RH, the reflection coefficient can be written as . If RH is added, the formula can be re-written as

where the detuning frequency is given by as the difference between the reference wavelength and the resonance one. is the coupling rate from the micro-ring to the bus waveguide [27], and and are the reflection and transmission coefficients of the RH, respectively. is the decay rate of the optical field, as related to the quality factor () of micro-ring, which depends on full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the resonance peak.

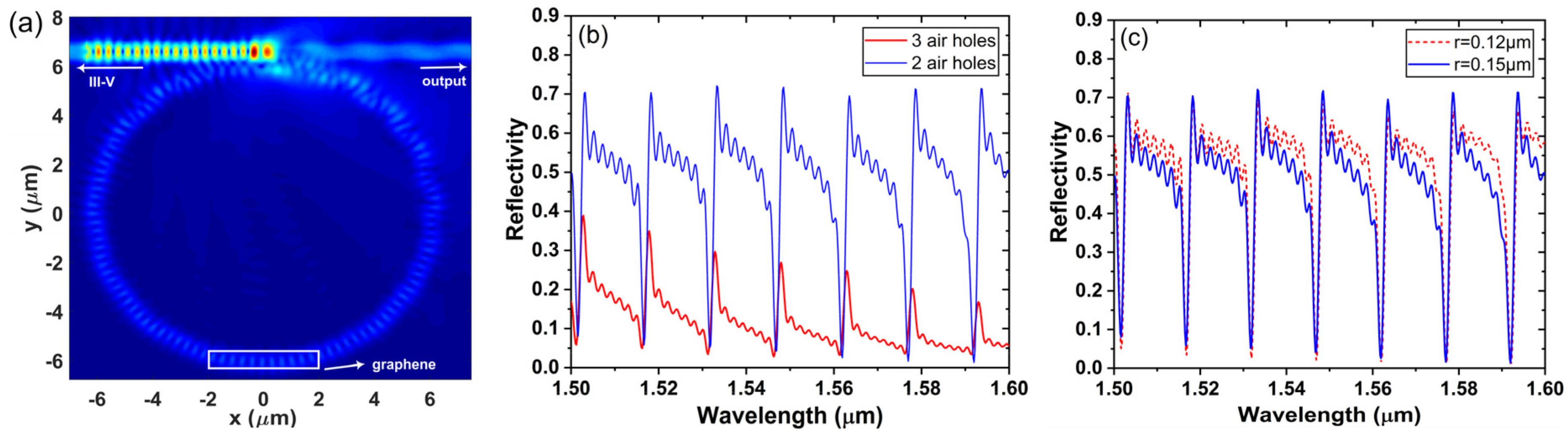

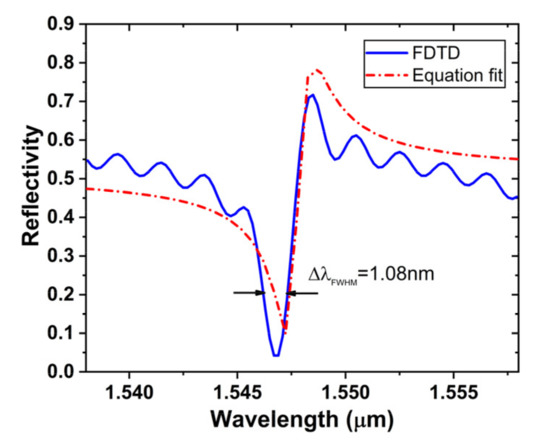

These coefficients can be fixed by fitting the equation with FDTD data, as calculated below: the electric field distribution of the Fano mirror is shown in Figure 2a, and the reflection spectra of the Fano mirror for different RH numbers and radii are in Figure 2b,c. From the plots, we can see that as the number of air holes increases, the insertion loss becomes larger due to stronger RH scattering, and the reflection coefficient also increases if the hole diameter changes from 120 nm to 150 nm.

Figure 2.

(a) Electric field distribution in the micro-ring for 0.15-μm hole radius; reflective spectra of the Fano mirror for different (b) number and (c) radius, of the air holes.

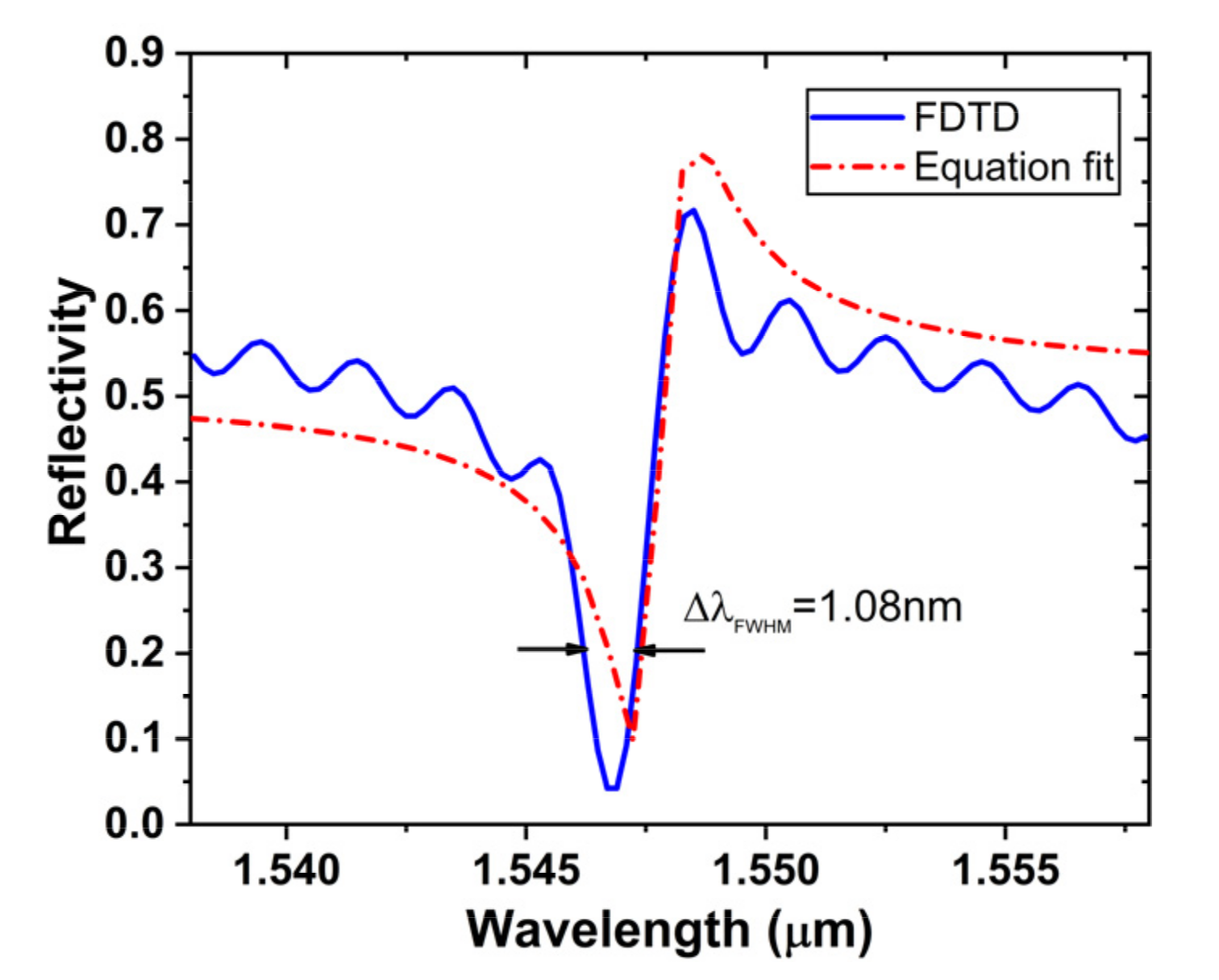

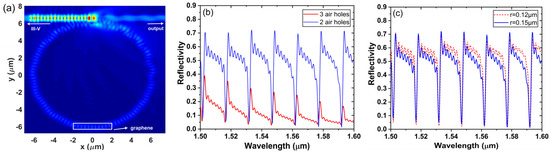

For RH radius , we find that the two curves match approximately when as is shown in Figure 3, whose analytical formula can be further applied in the next-step laser simulations. With the narrow-linewidth reflection-component ready, the saturable absorber can be introduced to generate self-pulsing for our proposed laser.

Figure 3.

Fitting curve of the Fano mirror using Equation (1) for the FDTD simulation results.

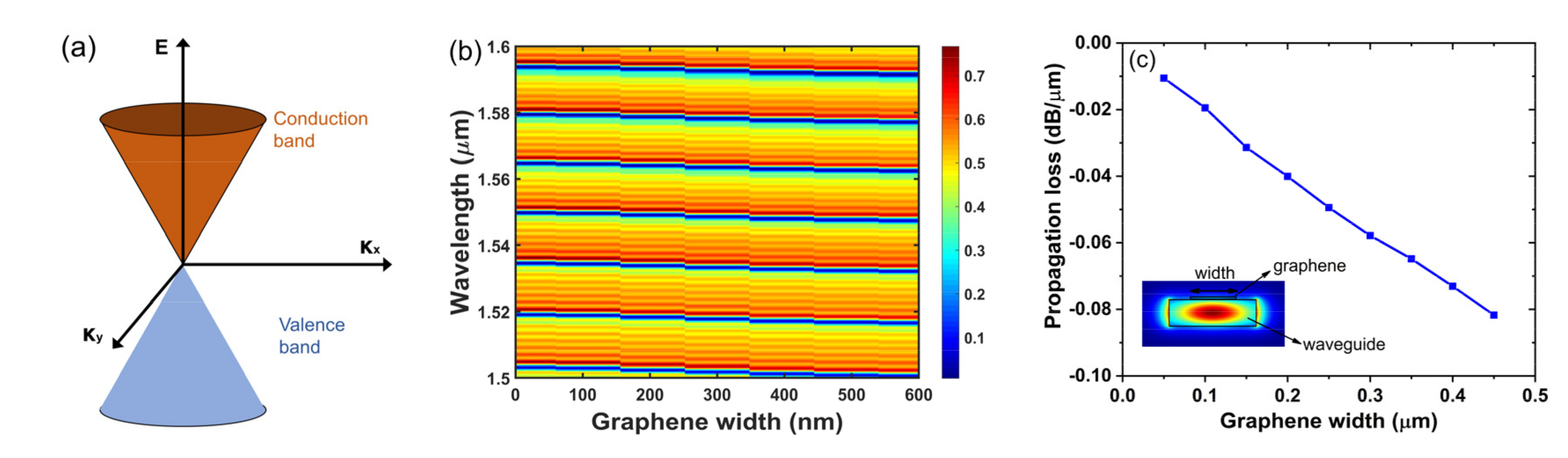

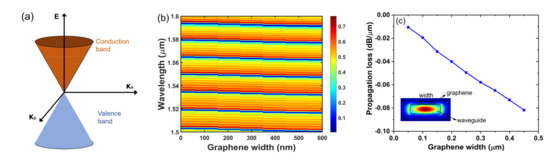

For details of the self-pulsing mechanism, we start with the band structure of the graphene as shown in Figure 4a, which has an intrinsic crossing of the conduction and valence bands at the Γ-point. This type of zero-bandgap 2D materials, including graphene (oxide) and black phosphorous, etc., can absorb light in a broad wavelength range as the semi-metal, which can induce large third-order nonlinearity factor as derived from the Kramers-Kronig relation for the real and imaginary parts of the refractive index [22]. The latter one can cause saturable absorption, when the conduction band is fully-filled due to the high level of optical pumping. The fast relaxation can be attributed to the carrier-carrier intraband scattering process that happens in fs/ps time frame [22]. Therefore, for lasers to work in the self-pulsing mode, the Fano effect could be combined with the graphene’s saturable absorption to use the narrow linewidth and high slope rate of the Fano reflection peak as an optical switch. For the self-pulsing dynamics, we will explore and discuss in details in Section 3, where the rate equation results can be used for demonstration.

Figure 4.

(a) Band structure of the graphene layer, (b) reflective spectrum of Fano mirror blue-shifts at wider graphene widths, and (c) propagation loss of the waveguide varied with the graphene width.

In addition, as shown in Figure 4b, the resonance wavelength of the Fano mirror blue-shifts when the graphene width increases. This is due to decrease in effective index of the guided mode, which extends more into the wider graphene layer that has relatively smaller refractive index and higher optical loss, as in Figure 4c. The averaged loss , as calculated by solving for eigenmode of the graphene covered silicon waveguide, is around 0.231 dB (for the 300 nm × 4 μm rectangular sheet of the graphene cover, with propagation loss of 0.0578 dB/μm, as shown in Figure 4c).

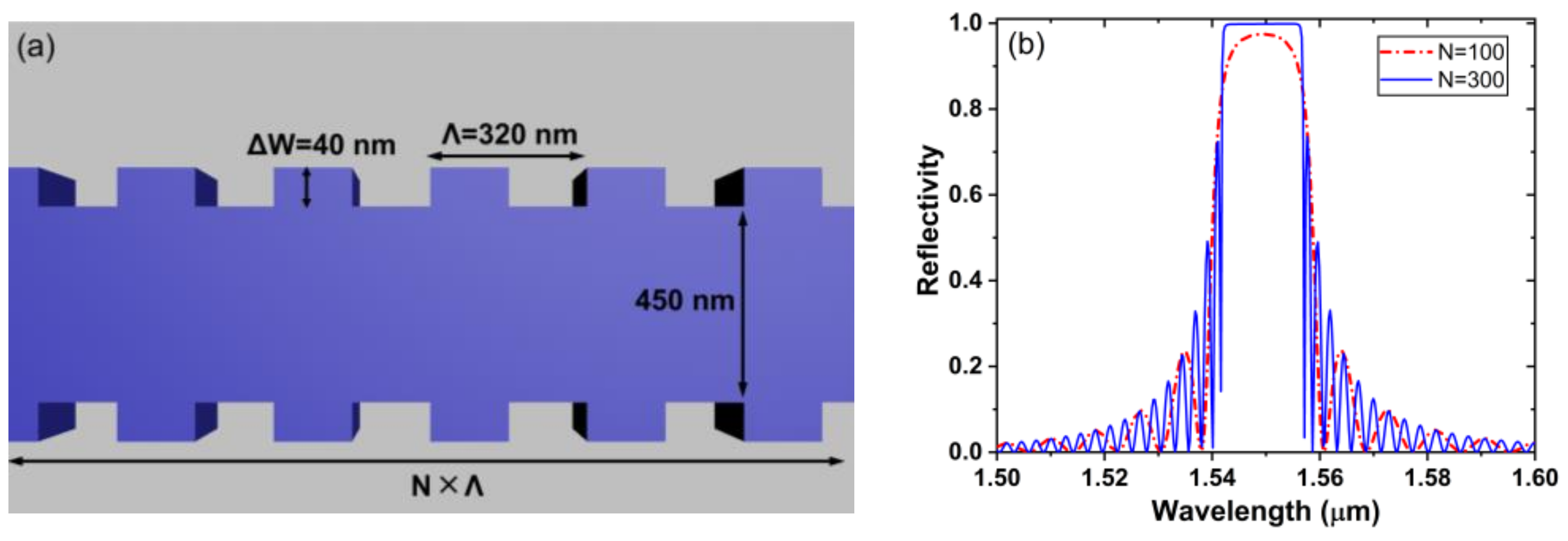

2.2. Bragg Mirrorr

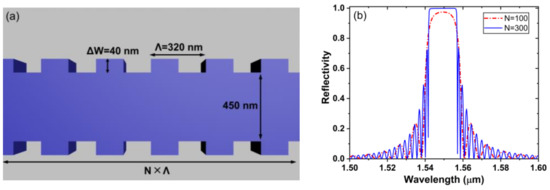

Figure 5a shows the structure of the surface grating on Si waveguide using sidewall corrugations. The width of each sidewall (ΔW) and grating period (Λ) is 40 and 320 nm, respectively. When the number of periods (N) increases to 300, the reflectivity increases from 0.973 to 0.996, as shown in Figure 5b. We choose the 96 μm length to ensure the low threshold and high wavelength selectivity.

Figure 5.

(a) Left mirror based on silicon waveguide grating, (b) reflective spectrum.

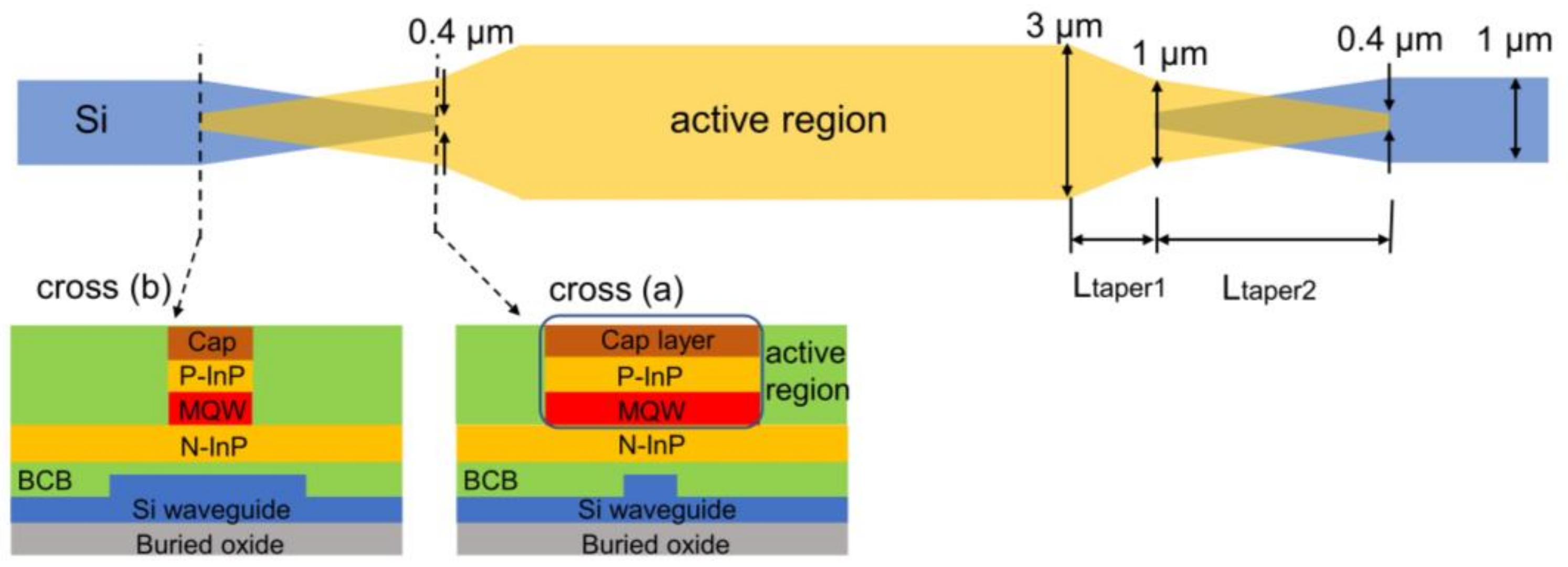

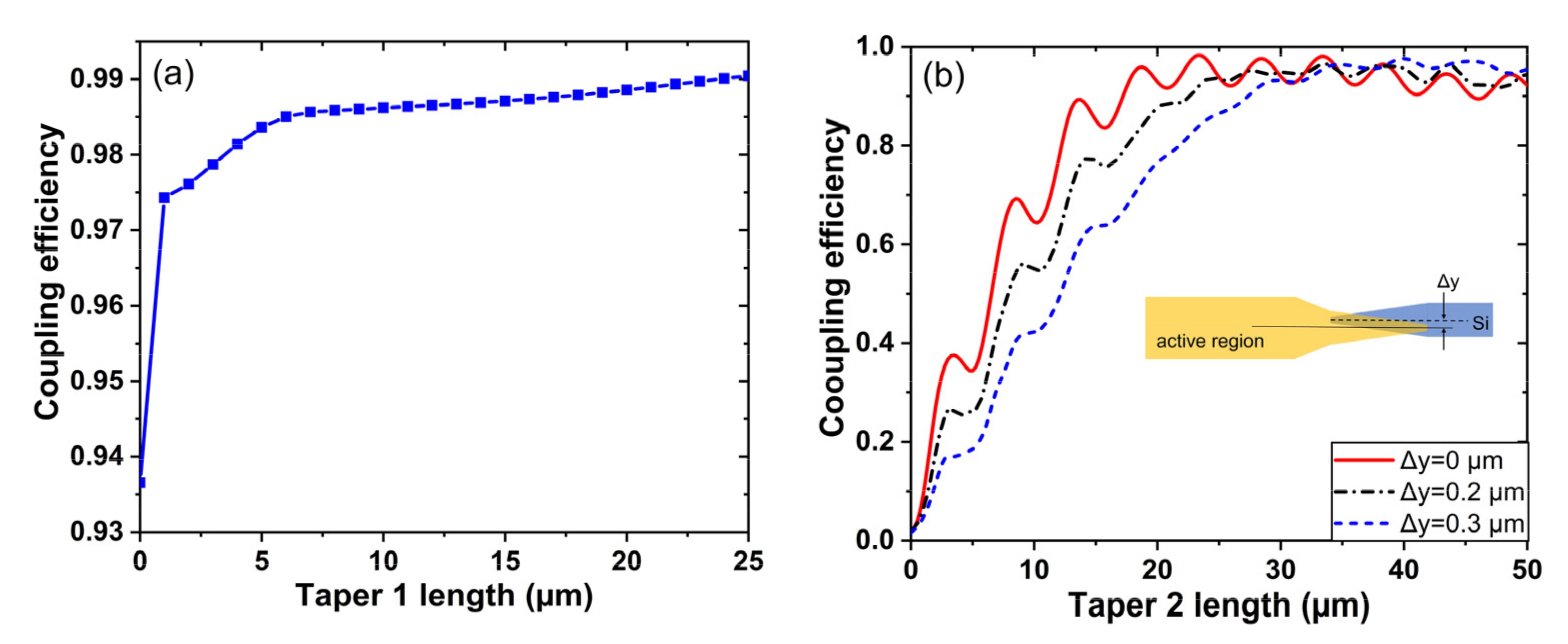

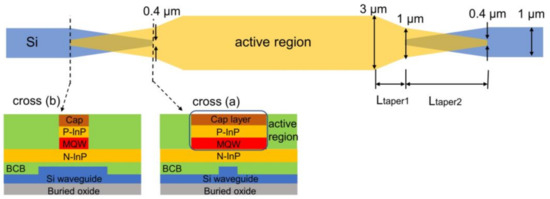

2.3. Taper Region

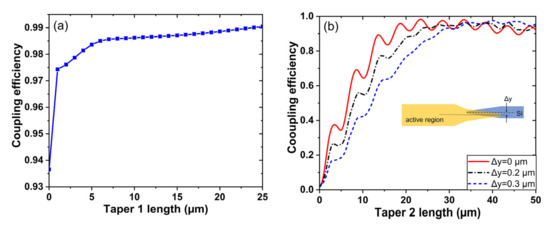

The III-V taper is used to couple light adiabatically from the MQW region to the Si waveguide, with no significant reflections to avoid inducing the multi-cavity effect [28], except for the Bragg and Fano mirrors etched on the silicon layer. Then, we need to minimize the coupling loss between the active region and the silicon waveguide, as shown in Figure 6, where the InP layer is adhesively bonded by Benzocyclobutene (BCB, n = 1.57) to the Si wafer with a spacing distance of 80 nm. Since the waveguide widths of the two tapers vary along the propagation direction, both of the propagation coefficients become equal at certain position, where their effective refractive indices of the guide-modes match. By sweeping the taper1/taper2 length by the eigenmode-expansion (EME) method, the optimum lengths are designed as and , with 98.8% and 96.7% for the coupling efficiencies, as illustrated in Figure 7a,b, respectively.

Figure 6.

The III-V/Si taper region, with the materials and dimension values marked in the insert.

Figure 7.

The coupling efficiency for different length of (a) taper1 and (b) taper2 if the alignment has a mismatch, as shown in the insert.

Alignment accuracy during III-V/Si integration can also affect the coupling efficiency considerably, where fluctuations in the curves may be caused by the interference of the reflected and incident fields at different Δy values from 0 to 0.3 μm.

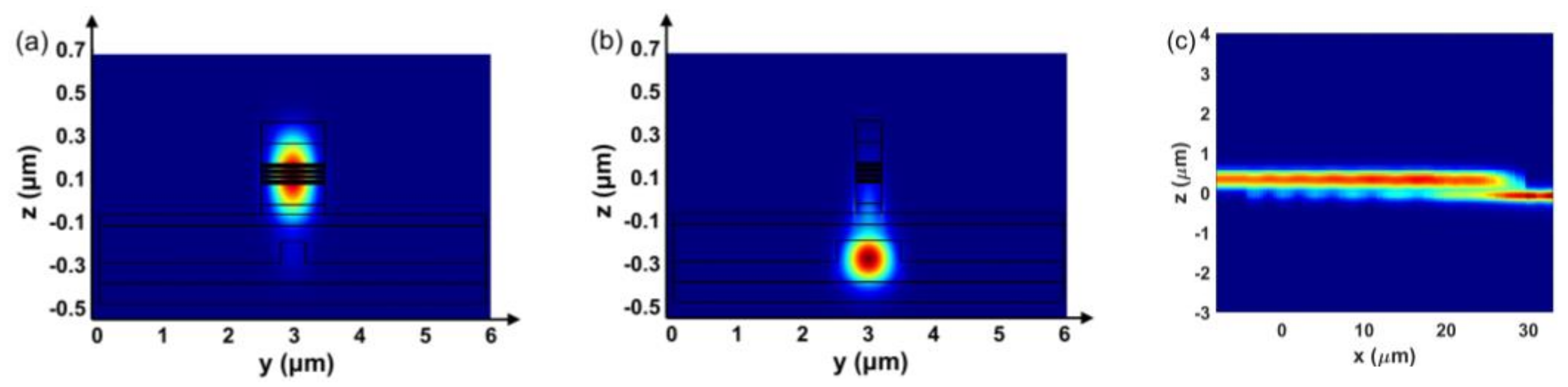

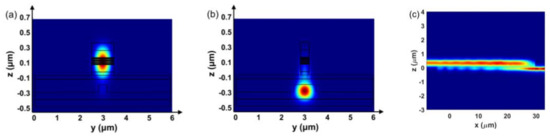

The fundamental modes in the ends of both active region and Si tapers are shown in Figure 8a,b for the cross sections marked as Figure 6a,b, while Figure 8c shows the light propagation in the x-z plane. The confinement factor () is calculated to be 0.047 from the field integration at MQW for use in the following rate equations.

Figure 8.

Mode distributions at the end of (a) active region taper and (b) Si taper, whose x positions are marked by cross (a) and cross (b) in Figure 6, respectively; and (c) the light propagation from III-V to Si in the x-z plane.

2.4. MQW Design

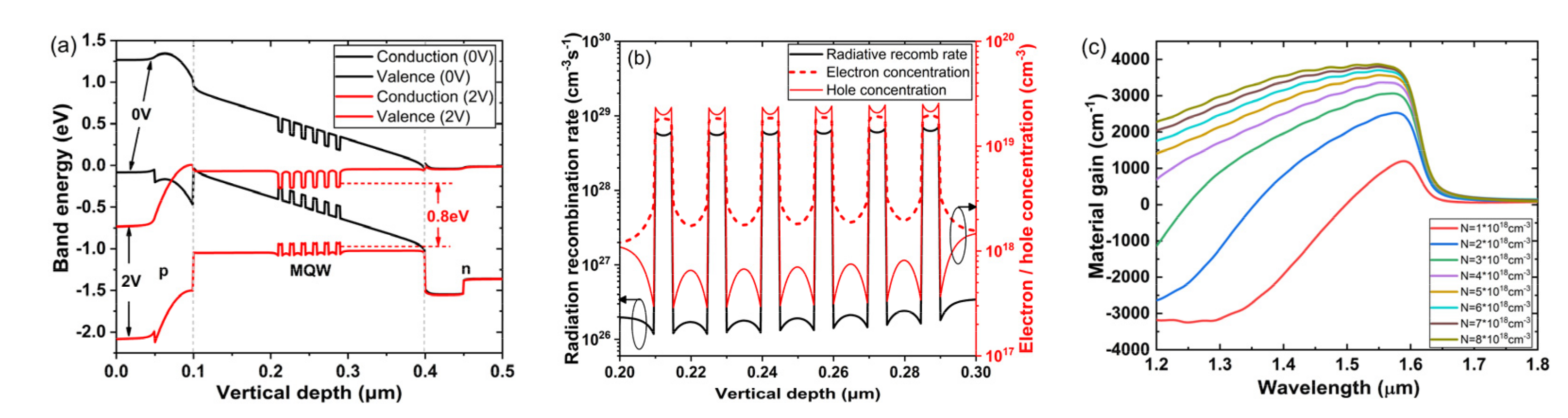

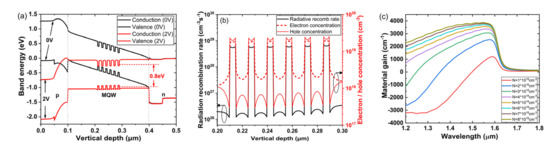

For the active region, InAlGaAs/InP MQWs are used with the detailed parameters as listed in Table 1. The band structures of gain region under 0 and 2 V bias voltages, as well as the carrier concentrations and radiative recombination, are calculated using the Silvaco Atlas package [29], as shown in Figure 9 a,b. The material gain curves for the MQWs at different carrier densities are plotted in Figure 9c, such that the gain coefficient () is chosen to be 3800 cm−1 at 1.5 μm, as in Table 2, for our next-step laser simulations. The MQW modal gain is given by , where is the confinement factor, is the gain saturation coefficient, and is the photon density.

Table 1.

Structural parameters for the cross-section.

Figure 9.

(a) Band structure of the quantum well active region under 0 and 2 V applied voltage, (b) electron-hole pair concentration and radiative recombination rate in the QW region under 2 V voltage, and (c) material gain curves for the active region.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters for the rate equation.

3. Laser Dynamics

3.1. Numerical Model

After optimization for each component of the laser, the light-current property can be calculated by the rate equation to describe the photon dynamics of the hybrid laser as

where and are the fields in the laser cavity and micro-ring, is the linewidth enhancement factor, is the group velocity, is the internal loss, the spontaneous noise is driven by and , and the − (+) sign means an odd (even) mode in the cavity. Here, is the waveguide internal loss, as shown in Figure 4c, which also includes the SA loss for the graphene layer, as given by . is the linear absorption coefficient, and is the saturation density of the optical field in the ring covered by the graphene layer [22]. The round-trip photon lifetime in the laser cavity is .

For the carrier equation that governs the conversion from electrons to photons, we can write

where is the injection efficiency of the current , is volume of the active region, is the carrier lifetime, and and are bimolecular and Auger recombination coefficients, respectively [30]. The scattering parameter is related to the optical field intensity and threshold gain in the cavity.

Therefore, the output power can be calculated as [31]

where is the group refractive index. Other parameters not mentioned here are listed in Table 2, as obtained from the FDTD/gain calculations.

3.2. Device Performance

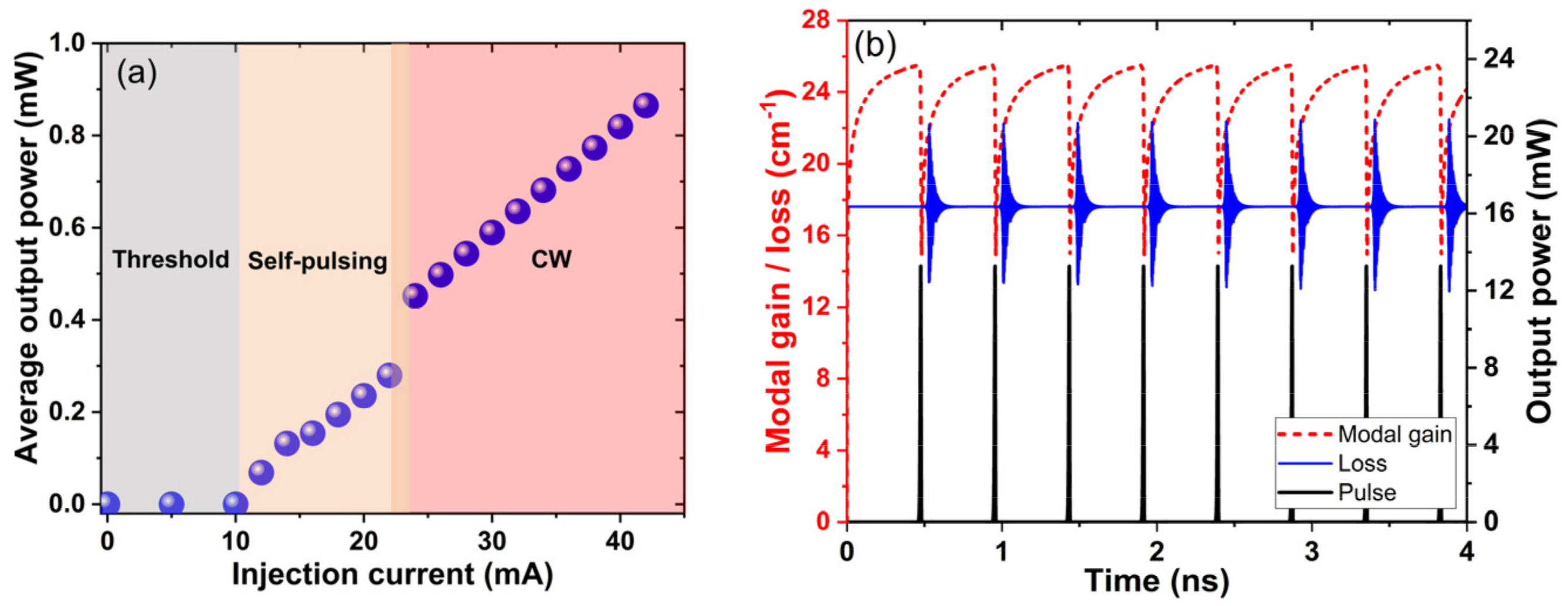

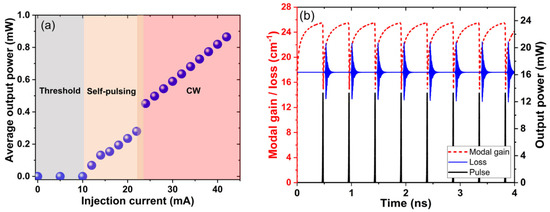

As shown in Figure 10a, the device has a lasing threshold of 10 mA current injection in the self-pulsing mode (until up to 22 mA). The modal gain and loss vary dynamically as in Figure 10b, and the pulse appears at the point when they cross with each other. If the injection continues to increase, the minimum of the modal gain would gradually exceed the upper bound of the loss curve, such that the laser switches to the CW mode with higher average output power.

Figure 10.

(a) Time-averaged power versus injection current for the proposed laser, and (b) modal gain/loss with pulsed output power at I = 16 mA.

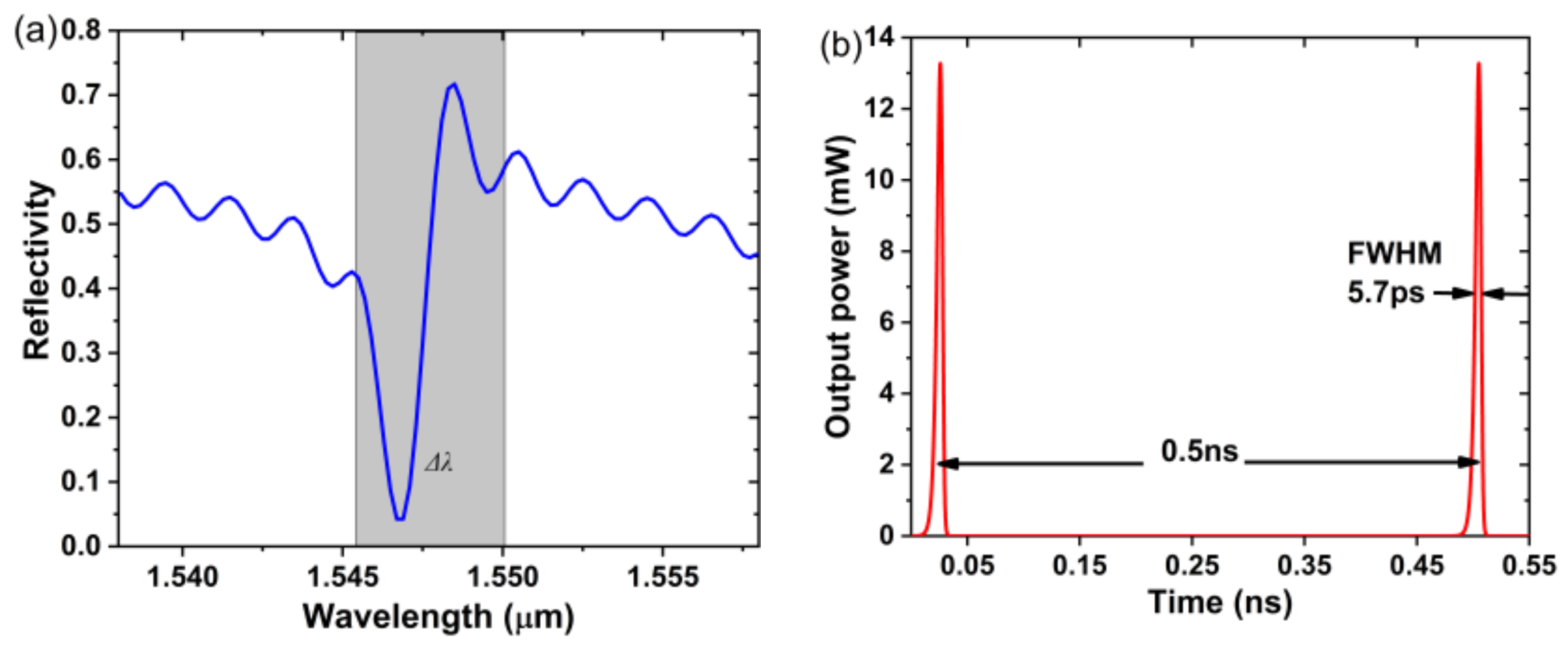

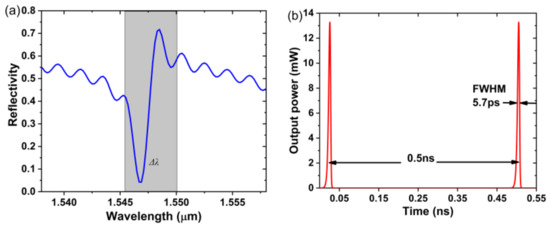

Here, the saturable absorption will dynamically change the Q-factor of the laser cavity and resonant frequency of the micro-ring at different incident optical power. The RH-induced Fano response provides a sharp variation of the reflection at different wavelengths, as indicated by the grey region in Figure 11a, such that the laser can be tuned at GHz rate by the high-speed switching of the Fano mirror resonance condition. The optical fields in the cavity interact with the injected carriers dynamically [32], i.e., spontaneous noise of the laser can perturb the device away from the quasi-equilibrium state, such that if the optical power is increased by the small noise, more carriers will be absorbed, leading to a reduced loss. This will positively feedback to the cavity, and the optical field further increases to consume more carriers until absorption saturation, which depletes the carriers instantaneously (in picosecond scale) when reaching the optical peak. However, the lowered material gain smaller than the total loss and the shift of resonance wavelength away from Fano reflection peak would rapidly turn off the pulse until enough carriers are accumulated for the next round pulsing [33]. Therefore, the combination of Fano switching and the SA effect can generate ps-pulsation iteratively and self-sustainably, as shown in Figure 11b. Here, the FWHM of the pulse is around 5.7 ps, and the repetition period is about 0.5 ns (i.e., 2 GHz).

Figure 11.

(a) Frequency shifting of Fano mirror where the gray region indicates the range of self-pulses. (b) FWHM details of the pulse train under 16 mA.

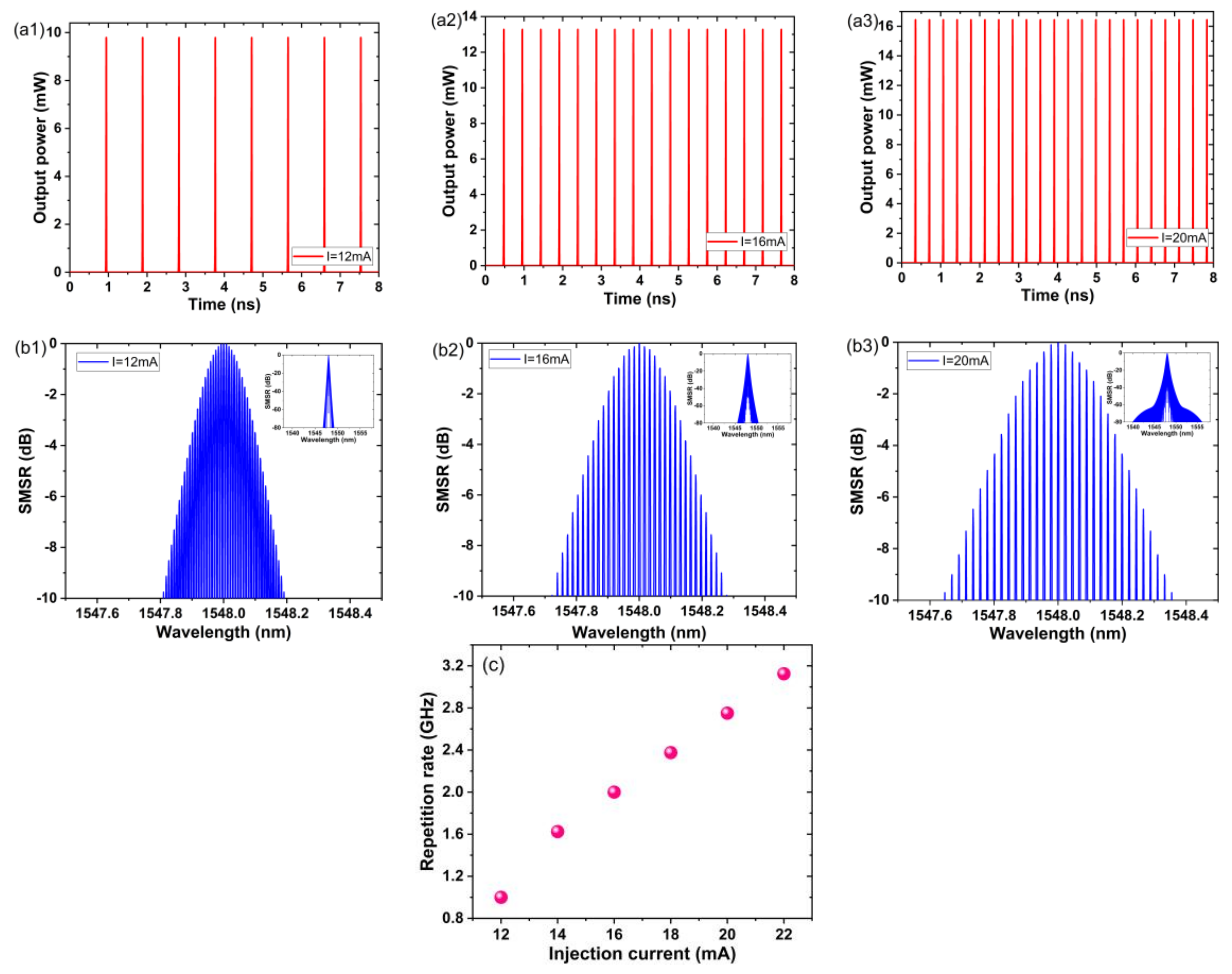

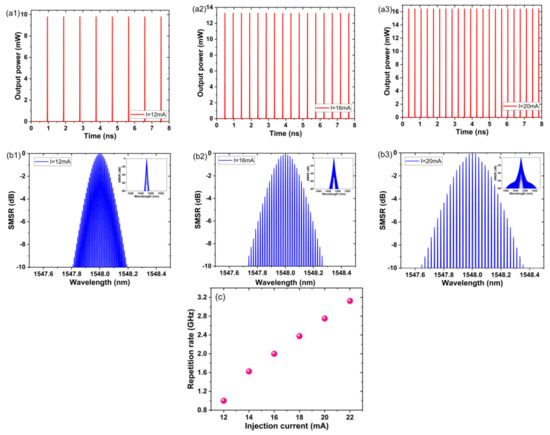

As the injection current increases from 12 to 20 mA, the repetition rate and spectrum of the optical pulse change accordingly, as in Figure 12. At higher injections, the pulses increase from 8 to 22 peaks within 8 ns, as well as the output power from 10 to 16 mW, as in Figure 12(a1–a3). Envelopes of the self-pulse spectra also broaden from 1547.8~1548.2 nm to the 1547.6~1548.4 nm for side-mode-suppression-ratio (SMSR) > −10 dB, as in Figure 12(b1–b3), where the inserts show the spectral envelope for SMSR>-80 dB. As summarized in Figure 12c, the pulse repetition rate increases linearly from 1 GHz to 3.12 GHz as the injection current increases, which may be due to faster built-up speed of the carriers at higher injection levels, such that, for the same level of SA, more pulses can be generated in the same time scale. The spectra broadening can also be due to the similar reason, i.e., as the pulse FWHM decreases from 6.5 to 5.7 and 5.1 ps, their Fourier transforms expand in frequency/wavelength domain from 0.4 to 0.56 and 0.72 nm, correspondingly.

Figure 12.

(a1–a3) The optical pulse trains, and (b1–b3) the corresponding spectra of the pulses for SMSR > −10 dB, where the inserts are for zoom-out of the spectra, and (c) the repetition rate, at different injection currents.

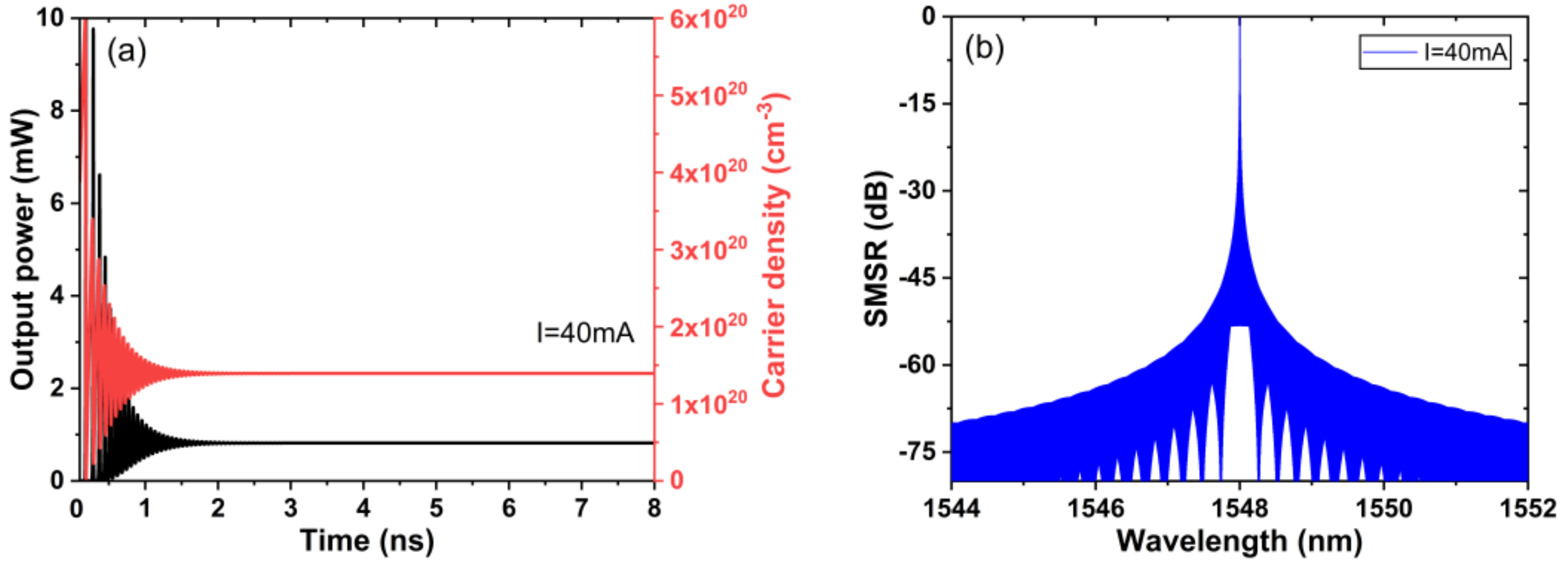

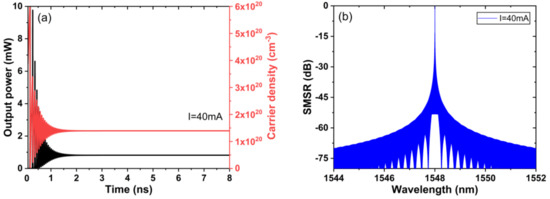

To further increase the current injection, modal gain can overcome the cavity loss, such that the device switches to the CW mode, with its optical power and carrier distribution at I = 40 mA, and the single-mode lasing spectrum due to the narrowband Fano mirror, as shown in Figure 13a,b, respectively.

Figure 13.

(a) CW output power and carrier density under 40 mA, and (b) optical spectrum near 1550 nm.

4. Conclusions

An electrically-pumped self-pulsing III-V/silicon hybrid laser based on the Fano resonance is proposed and analyzed, where the Fano cavity is formed by RH in the coupling region of the bus-waveguide and the graphene-covered micro-ring. The combination of Fano switching and the SA effect can generate ps-pulsation iteratively and self-sustainably. The left mirror of Si surface grating ensures enough reflection to improve the threshold current to about 10mA. In addition, the light coupling from the III-V to Si is realized by a two-stage taper, with more than 98.8% and 96.7% coupling efficiencies, respectively. The MQW regions are also calculated for the best performance of the active region. Rate equation study of the laser is demonstrated to characterize the influence of electrical injection on the laser output and the variation of self-pulsing. Within appropriate current range, the train of pulses can be generated with decreasing pulse width, expanding spectrum and increasing repetition rate, when the injection is increased (until CW-mode lasing). The FWHM of the pulse width decreases from 6.5 to 5.1 ps. Envelopes of the pulse-train spectra expand from 1547.8~1548.2 nm to the 1547.6~1548.4 nm. The pulse repetition rate increases linearly from 1 GHz to 3.12 GHz as the injection current increases to 22 mA. This self-pulsing laser can be used for the on-chip LiDAR, neuromorphic computation, and microwave photonics applications. The device can also be compatible with the CMOS platform for silicon-based photonic integration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L. and W.H.; project administration and funding acquisition, Y.L. and W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0209000, 2018YFB2200700).

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Y.L. thanks Yong Wang for the helpful discussion about the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Trocha, P.; Karpov, M.; Ganin, D.; Pfeiffer, M.H.P.; Kordts, A.; Wolf, S.; Krockenberger, J.; Marin-Palomo, P.; Weimann, C.; Randel, S.; et al. Ultrafast optical ranging using microresonator soliton frequency combs. Science 2018, 359, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knigge, A.; Klehr, A.; Wenzel, H.; Zeghuzi, A.; Fricke, J.; Maaßdorf, A.; Liero, A.; Tränkle, G. Wavelength-Stabilized High-Pulse-Power Laser Diodes for Automotive LiDAR. Phys. Status Solidi A 2018, 215, 1700439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, B.J.; Tait, A.N.; Ferreira de Lima, T.; Pernice, W.H.P.; Bhaskaran, H.; Wright, C.D.; Prucnal, P.R. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 2021, 15, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelfi, P.; Laghezza, F.; Scotti, F.; Serafino, G.; Capria, A.; Pinna, S.; Onori, D.; Porzi, C.; Scaffardi, M.; Malacarne, A.; et al. A fully photonics-based coherent radar system. Nature 2014, 507, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippenberg, T.J.; Holzwarth, R.; Diddams, S.A. Microresonator-Based Optical Frequency Combs. Science 2011, 332, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Haji, M.; Marsh, J.H.; Bryce, A.C. 490 fs pulse generation from a passive C-band AlGaInAs/InP quantum well mode-locked laser. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiessen, T.; Poon, J.K.S. 20 GHz Mode-Locked Laser Diodes with Integrated Optical Feedback Cavities in a Generic Monolithic InP Photonics Platform. IEEE Photonics J. 2017, 9, 1505010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.; Bente, E.A.J.M.; den Haan, E.; Heck, M.J.R. Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Unidirectionality in an Integrated Semiconductor Ring Mode-Locked Laser with Two Saturable Absorbers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2018, 54, 2000810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keyvaninia, S.; Uvin, S.; Tassaert, M.; Fu, X.; Latkowski, S.; Marien, J.; Thomassen, L.; Lelarge, F.; Duan, G.; Verheyen, P.; et al. Narrow-linewidth short-pulse III–V-on-silicon mode-locked lasers based on a linear and ring cavity geometry. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davenport, M.L.; Liu, S.; Bowers, J.E. Integrated heterogeneous silicon/III–V mode-locked lasers. Photonics Res. 2018, 6, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tran, M.A.; Guo, J.; Peters, J.; Komljenovic, T.; Malik, A.; Morton, P.A.; Bowers, J.E. High-power sub-kHz linewidth lasers fully integrated on silicon. Optica 2019, 6, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Haq, B.; Sprengel, S.; Malik, A.; Vasiliev, A.; Boehm, G.; Simonyte, I.; Vizbaras, A.; Vizbaras, K.; Van Campenhout, J.; et al. Widely tunable III–V/silicon lasers for spectroscopy in the short-wave infrared. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2019, 25, 1502412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Park, J.-S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Jurczak, P.; Seeds, A.; Liu, H. Integration of III–V lasers on Si for Si photonics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2019, 66, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvaninia, S.; Uvin, S.; Tassaert, M.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Latkowski, S.; Marien, J.; Thomassen, L.; Lelarge, F.; Duan, G.; et al. III–V-on-silicon anti-colliding pulse-type mode-locked laser. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 3057–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, S.; Norberg, E.; Komljenovic, T.; Davenport, M.; Fish, G.; Bowers, J.E. Hybrid Silicon Colliding-Pulse Mode-Locked Lasers With On-Chip Stabilization. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2015, 21, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyvers, S.; Haq, B.; Op de Beeck, C.; Poelman, S.; Hermans, A.; Wang, Z.; Gocalinska, A.; Pelucchi, E.; Corbett, B.; Roelkens, G.; et al. Low Noise Heterogeneous III–V-on-Silicon-Nitride Mode-Locked Comb Laser. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2000485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, C.; Liu, Y. Dual-waveband self-pulsed laser at 3 μm and 2.1 μm. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2019, 31, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akahane, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Umezawa, T.; Yamamoto, N. High-frequency short-pulse generation with a highly stacked in as quantum dot mode-locked laser diode. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, SBBH02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhamiardakani, H.; Diels, J.-C. Controlling group and phase velocities in bidirectional mode-locked fiber lasers. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 2903–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaugg, C.A.; Sun, Z.; Wittwer, V.J.; Popa, D.; Milana, S.; Kulmala, T.S.; Sundaram, R.S.; Mangold, M.; Sieber, O.D.; Golling, M.; et al. Ultrafast and widely tuneable vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting laser, mode-locked by a graphene-integrated distributed Bragg reflector. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 31548–31559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, Z.; Martinez, A.; Wang, F. Optical modulators with 2D layered materials. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamashita, S. Nonlinear optics in carbon nanotube, graphene, and related 2D materials. APL Photonics 2019, 4, 034301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FDTD Solution and Mode Solution. Available online: https://www.lumerical.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Gu, L.; Fang, L.; Fang, H.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Gan, X. Fano resonance lineshapes in a waveguide-microring structure enabled by an air-hole. APL Photonics 2020, 5, 016108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lee, R.K.; Yariv, A. Scattering-theory analysis of waveguide-resonator coupling. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 7389–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. Sharp asymmetric line shapes in side-coupled waveguide-cavity systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmussen, T.S.; Yu, Y.; Mork, J. Suppression of coherence collapse in semiconductor Fano lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 233904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davenport, M.L.; Heck, M.J.R.; Bowers, J.E. Characterization of a Hybrid Silicon-InP Laser Tapered Mode Converter. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe (CLEO EUROPE), Munich, Germany, 12–16 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SILVACO. Semiconductor Process and Device Simulation. Atlas Package. Available online: https://silvaco.com/tcad/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Yanping, X.; Wei-Ping, H.; Xun, L. An efficient solution to the standing-wave approach based on cold cavity modes for simulation of DFB lasers. J. Lightwave Technol. 2009, 27, 3227–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromborg, B.; Olesen, H.; Pan, X.; Saito, S. Transmission line description of optical feedback and injection locking for Fabry-Perot and DFB lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1987, 23, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xue, W.; Semenova, E.; Yvind, K.; Mork, J. Demonstration of a self-pulsing photonic crystal Fano laser. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohtsubo, J. Semiconductor Lasers Stability, Instability and Chaos, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).