Multiband Infrared Photodetection Based on Colloidal Quantum Dot

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

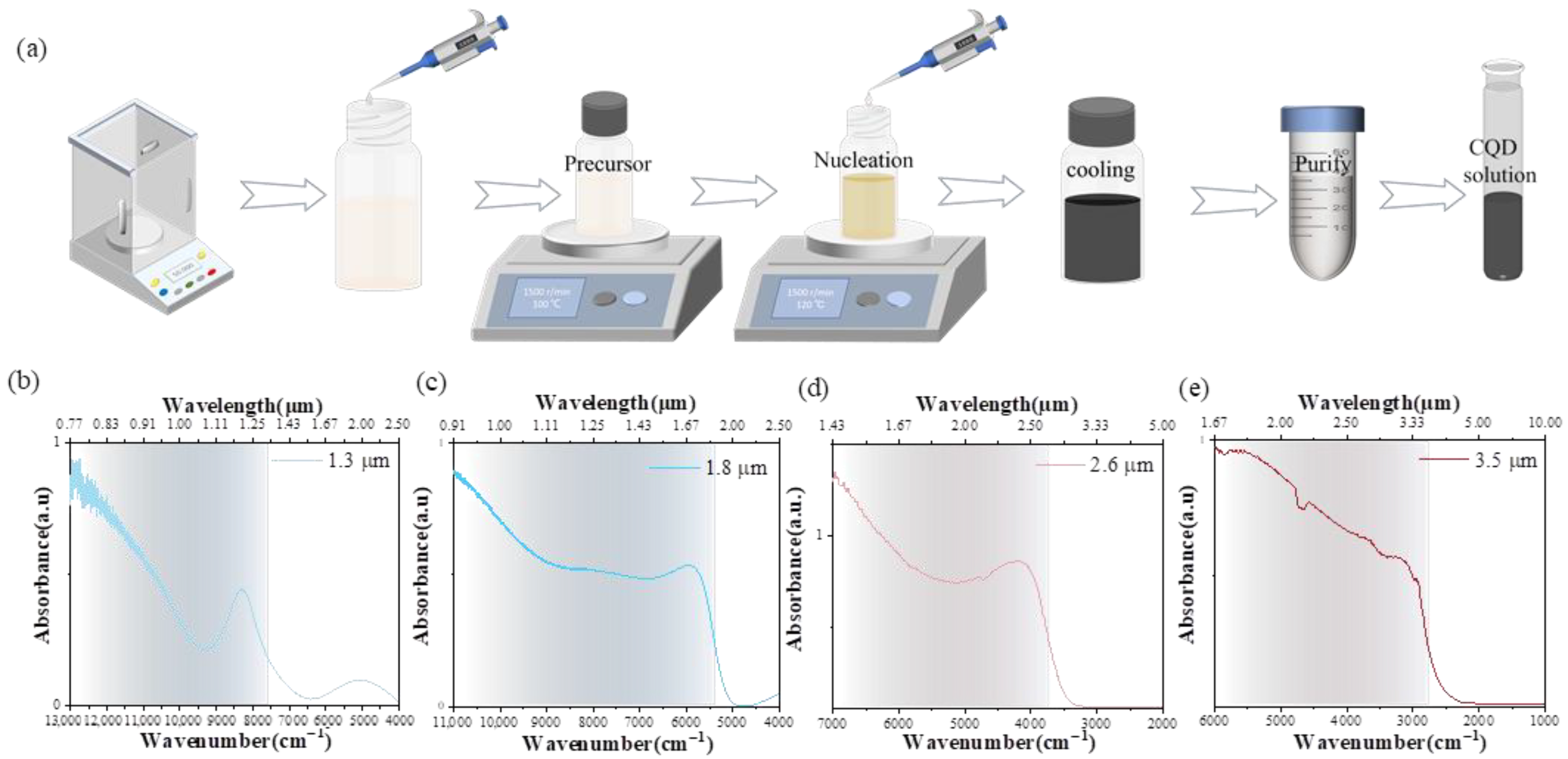

2.1. Materials Synthesis

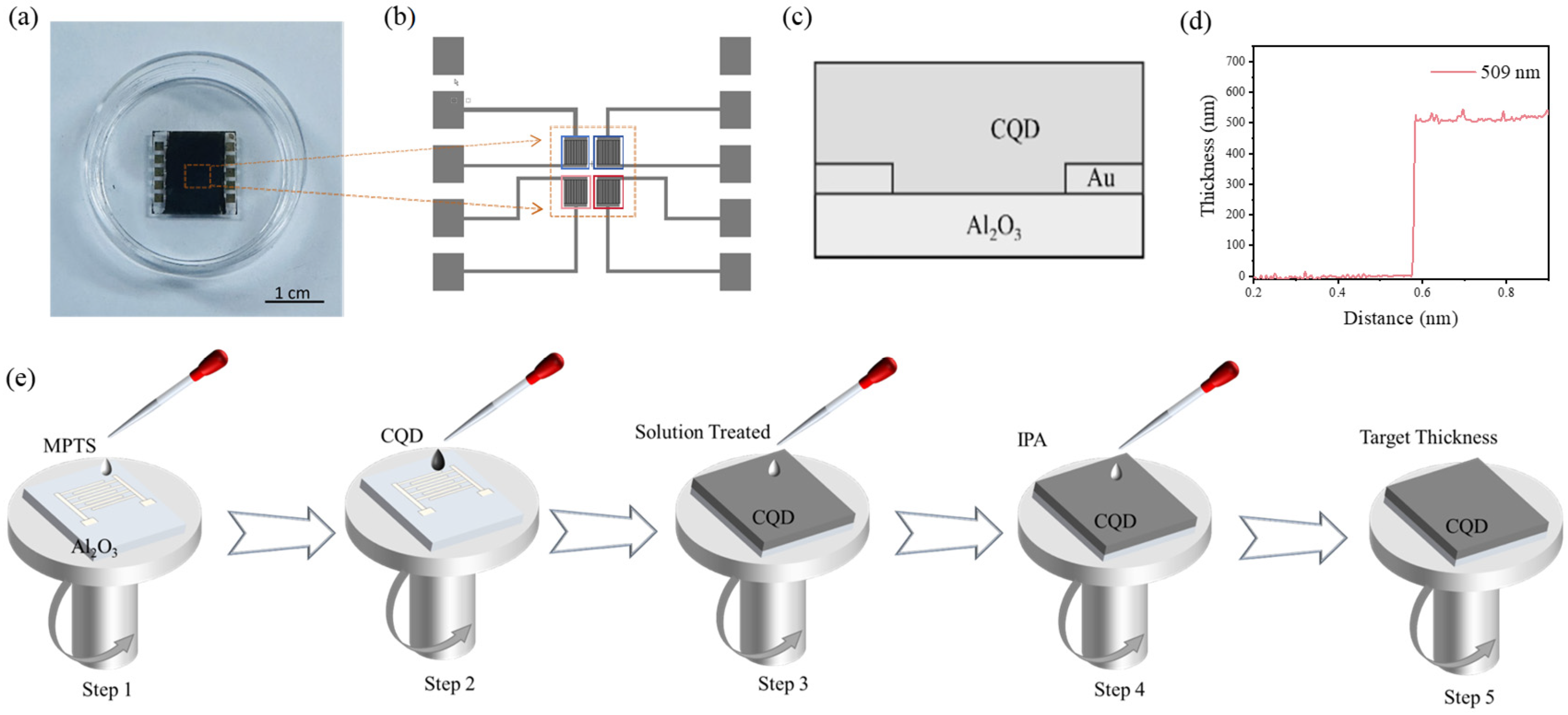

2.2. Photodetector Structure and Fabrication

- (1)

- Substrate Pretreatment:

- (2)

- Film Deposition and Processing

- (3)

- Layer Completion and Thickness Control

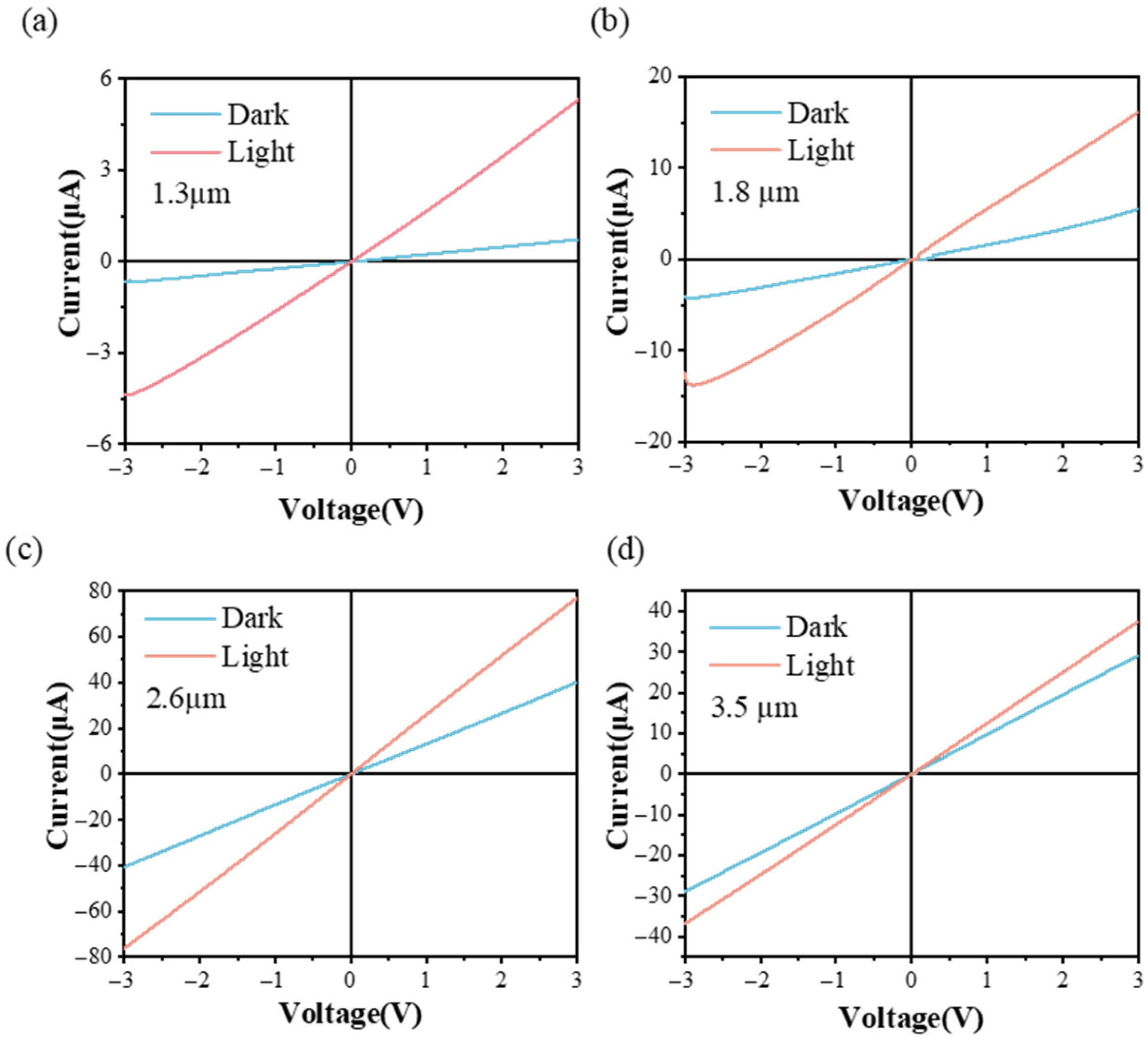

2.3. Photodetector Characterization

- (1)

- Responsivity (R) and Detectivity (D*)

- (2)

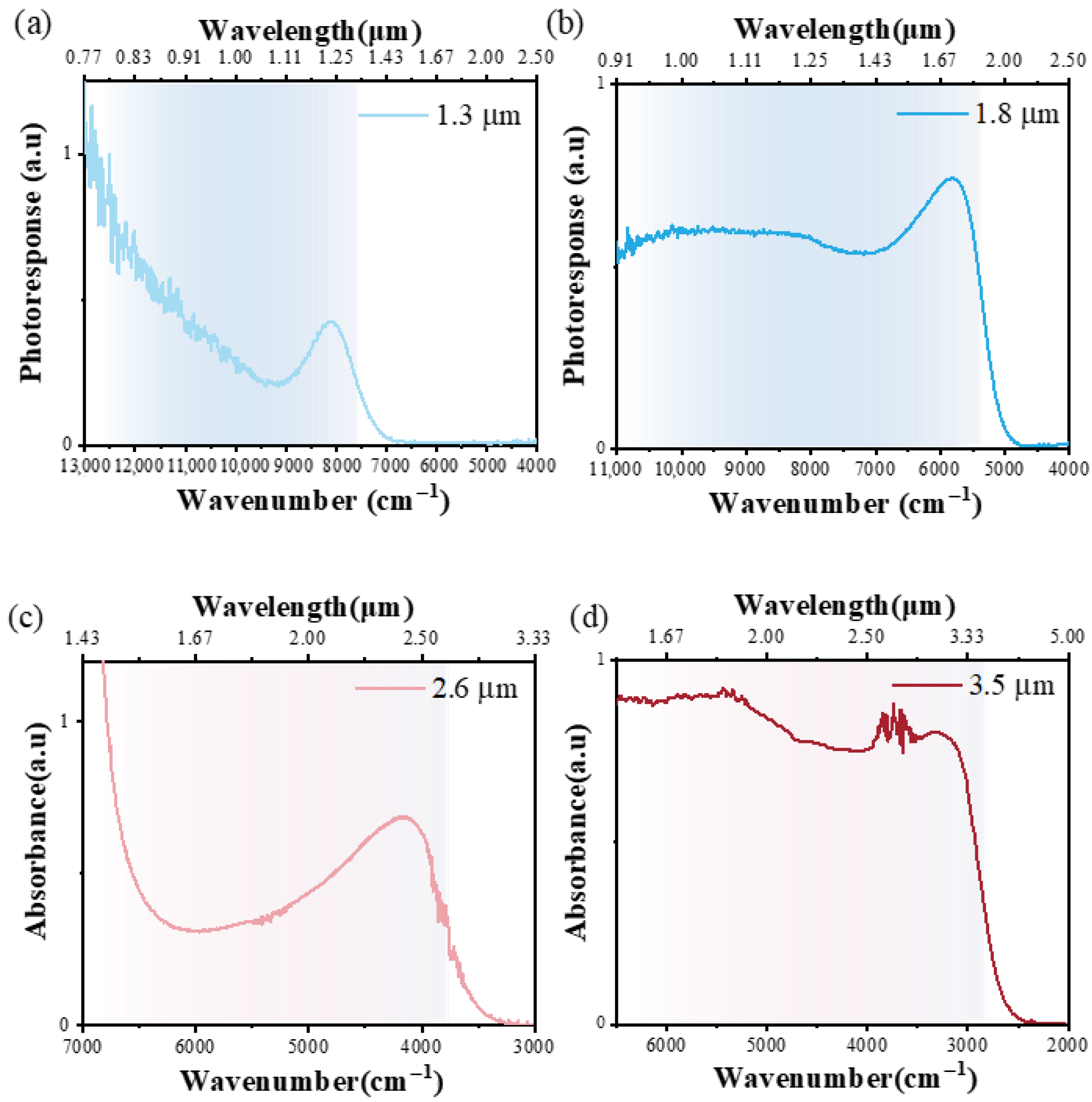

- Photoresponse

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogalski, A.; Antoszewski, J.; Faraone, L. Third-generation infrared photodetector arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 091101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; Chen, L.; Huang, F.; Wang, S. Camouflaged Target Detection Based on Snapshot Multispectral Imaging. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumis, M.S.; Viciani, S.; Borri, S.; Patimisco, P.; Sampaolo, A.; Scamarcio, G.; De Natale, P.; D’Amato, F.; Spagnolo, V. Widely-tunable mid-infrared fiber-coupled quartz-enhanced photoacoustic sensor for environmental monitoring. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 28222–28231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.A. Common Aperture Multi-Spectral Optics for Military Applications. Proc. SPIE 2012, 8353, 83531X. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.A. Optical Design of Common Aperture, Common Focal Plane, Multispectral Optics for Military Applications. Opt. Eng. 2013, 52, 061308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhong, Y.; Bruns, O.; Liang, Y.; Dai, H. In vivo NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging for Biology and Medicine. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopytko, M.; Gawron, W.; Kębłowski, A.; Stępień, D.; Martyniuk, P.; Jóźwikowski, K. Numerical analysis of HgCdTe dual-band infrared detector. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2019, 51, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, J.; Muszalski, J.; Piotrowski, J. Recent advances in InGaAs detector technology. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2004, 201, 2281–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimov, A.; Efros, A.L.; Onushchenko, A.A. Quantum size effect in semiconductor microcrystals. Solid State Commun. 1993, 88, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia de Arquer, F.P.; Talapin, D.V.; Klimov, V.I.; Arakawa, Y.; Bayer, M.; Sargent, E.H. Semiconductor quantum dots: Technological progress and future challenges. Science 2021, 373, eaaz8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, D.M.; Nugraha, M.I.; Bisri, S.Z.; Sytnyk, M.; Heiss, W.; Loi, M.A. Reducing charge trapping in PbS colloidal quantum dot solids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 112104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Precursor Chemistry Enables the Surface Ligand Control of PbS Quantum Dots for Efficient Photovoltaics. Adv. Sci. 2022, 10, 2204655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, D.Y.; Baek, S.; Yu, H.; So, F. Inorganic UV-Visible-SWIR Broadband Photodetector Based on Monodisperse PbS Nanocrystals. Small 2016, 12, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Hu, H.; Lv, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wang, B.; He, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Yu, M.; et al. Ligand-Engineered HgTe Colloidal Quantum Dot Solids for Infrared Photodetectors. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3465–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Luo, Y.; Hao, Q.; Cao, J.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M. Low Dark-Current Quantum-Dot Infrared Imager. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 4290–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, K.A.; Hu, S.; Sokolova, A.V.; Portniagin, A.S.; Chen, D.; Kershaw, S.V.; Rogach, A.L. Obviating Ligand Exchange Preserves the Intact Surface of HgTe Colloidal Quantum Dots and Enhances Performance of Short Wavelength Infrared Photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2306518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lan, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hudson, M.H.; Talapin, D.V.; Guyot-Sionnest, P. High Carrier Mobility in HgTe Quantum Dot Solids Improves Mid-IR Photodetectors. ACS Photonics 2019, 6, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Chen, M.; Luo, Y.; Qin, T.; Tang, X.; Hao, Q. High-operating-temperature mid-infrared photodetectors via quantum dot gradient homojunction. Light Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillas, A.; Guyot-Sionnest, P. Uncooled high detectivity mid-infrared photoconductor using HgTe quantum dots and nanoantennas. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 8952–8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuleyan, S.E.; Guyot-Sionnest, P.; Delerue, C.; Allan, G. Mercury telluride colloidal quantum dots: Electronic structure, size-dependent spectra, and photocurrent detection up to 12 μm. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8676–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peterson, J.C.; Guyot-Sionnest, P. Intraband Transition of HgTe Nanocrystals for Long-Wave Infrared Detection at 12 μm. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7530–7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Hao, Q.; Chen, M. Very long wave infrared quantum dot photodetector up to 18 μm. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejović, V.; Georgitzikis, E.; Lieberman, I.; Malinowski, P.E.; Heremans, P.; Cheyns, D. Photodetectors Based on Lead Sulfide Quantum Dot and Organic Absorbers for Multispectral Sensing in the Visible to Short-Wave Infrared Range. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Qin, T.; Mu, G.; Zhang, S.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M.; Tang, X. Band-engineered dual-band visible and short-wave infrared photodetector with metal chalcogenide colloidal quantum dots. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 2842–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lai, K.W.C. Scalable Fabrication of Infrared Detectors with Multispectral Photoresponse Based on Patterned Colloidal Quantum Dot Films. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, S.M.; Kang, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, M.J.; Han, K.; Facchetti, A.; Kim, M.; Park, S.K. A skin-like two-dimensionally pixelized full-color quantum dot photodetector. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Gassenq, A.; Justo, Y.; Yakunin, S.; Heiss, W.; Hens, Z.; Roelkens, G. Short-wave infrared colloidal quantum dot photodetectors on silicon. Proc. SPIE 2013, 8631, 863127. [Google Scholar]

| Wavelength (μm) | Reaction Temperature (℃) | Growth Time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.3 | 120 | 2 |

| 1.8 | 60 | 5 |

| 2.6 | 80 | 4 |

| 3.5 | 90 | 6 |

| Pixel | P (μW) | Iph (μA) | R (A/W) | D* (Jones) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.3 μm PbS CQD | 5.30 | 4.61 | 0.87 | 8.87 × 1010 |

| 1.8 μm HgTe CQD | 1.98 | 10.67 | 5.39 | 2.01 × 1011 |

| 2.6 μm HgTe CQD | 15.14 | 36.91 | 2.43 | 3.36 × 1010 |

| 3.5 μm HgTe CQD | 38.51 | 8.41 | 0.22 | 3.54 × 109 |

| Materials | Device Structure | Operating Temperature | Bias (V) | Wavelength (μm) | Detectivity (Jones) | Responsivity (A/W) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PbS CQDs/OPD-PbS CQDs | Vertical stacking | / | 1 | 0.4–1.0 | / | EQE = 70% @ 500nm | [23] |

| 0.8–1.2 | / | EQE = 30% @ 1150nm | |||||

| HgTe/CdTe CQDs | Vertical stacking | Room tempreture | +3 | 0.7 | 1.1 × 1011 | 0.5 | [24] |

| −2 | 2.1 | 4.5 × 1011 | 1.1 | ||||

| HgTe CQD | Planar patterning | room tempreture | <10 | 4.8 | 2 × 107@2μm | 0.1@2μm | [25] |

| 6.0 | 1.25 × 107@4μm | 0.07@4μm | |||||

| 9.5 | 1.0 × 107@7μm | 0.05@7μm | |||||

| PbS/CdSe/CdS CQD | Planar patterning | room tempreture | VD = 15 VG = −3 | 406 | 4.2 × 1017 | 8.3 × 103 | [26] |

| 530 | |||||||

| 630 | |||||||

| 1310 | |||||||

| PbS/HgTe CQD | Planar patterning | room tempreture | 3 | 1.3 | 8.87 × 1010 | 0.87 | This work |

| 1.8 | 2.01 × 1011 | 5.39 | |||||

| 2.6 | 3.36 × 1010 | 2.43 | |||||

| 3.5 | 3.54 × 109 | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Gan, Z.; Chen, M.; Hao, Q. Multiband Infrared Photodetection Based on Colloidal Quantum Dot. Photonics 2026, 13, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010089

Xu Y, Xue X, Wu L, Gan Z, Chen M, Hao Q. Multiband Infrared Photodetection Based on Colloidal Quantum Dot. Photonics. 2026; 13(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yingying, Xiaomeng Xue, Lixiong Wu, Zhikai Gan, Menglu Chen, and Qun Hao. 2026. "Multiband Infrared Photodetection Based on Colloidal Quantum Dot" Photonics 13, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010089

APA StyleXu, Y., Xue, X., Wu, L., Gan, Z., Chen, M., & Hao, Q. (2026). Multiband Infrared Photodetection Based on Colloidal Quantum Dot. Photonics, 13(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics13010089