A Long-Period Grating Based on Double-Clad Fiber for Multi-Parameter Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Principle

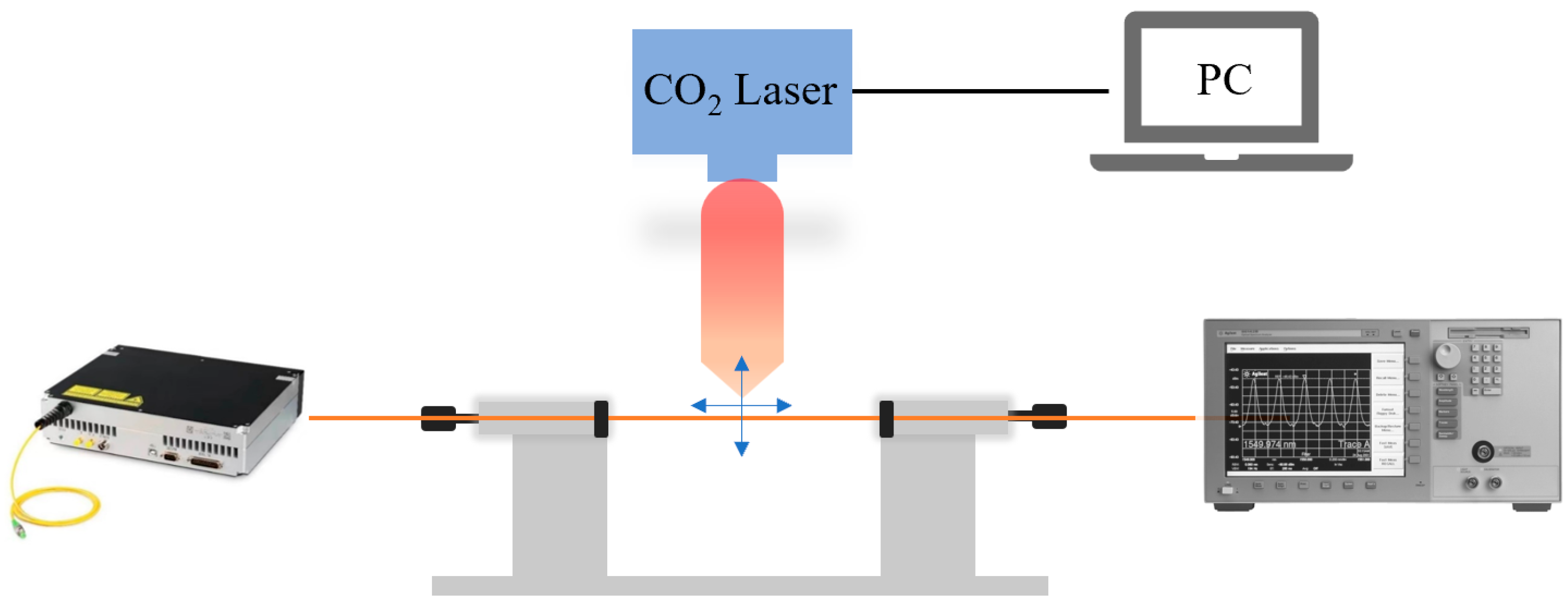

2.2. Fabrication

3. Results

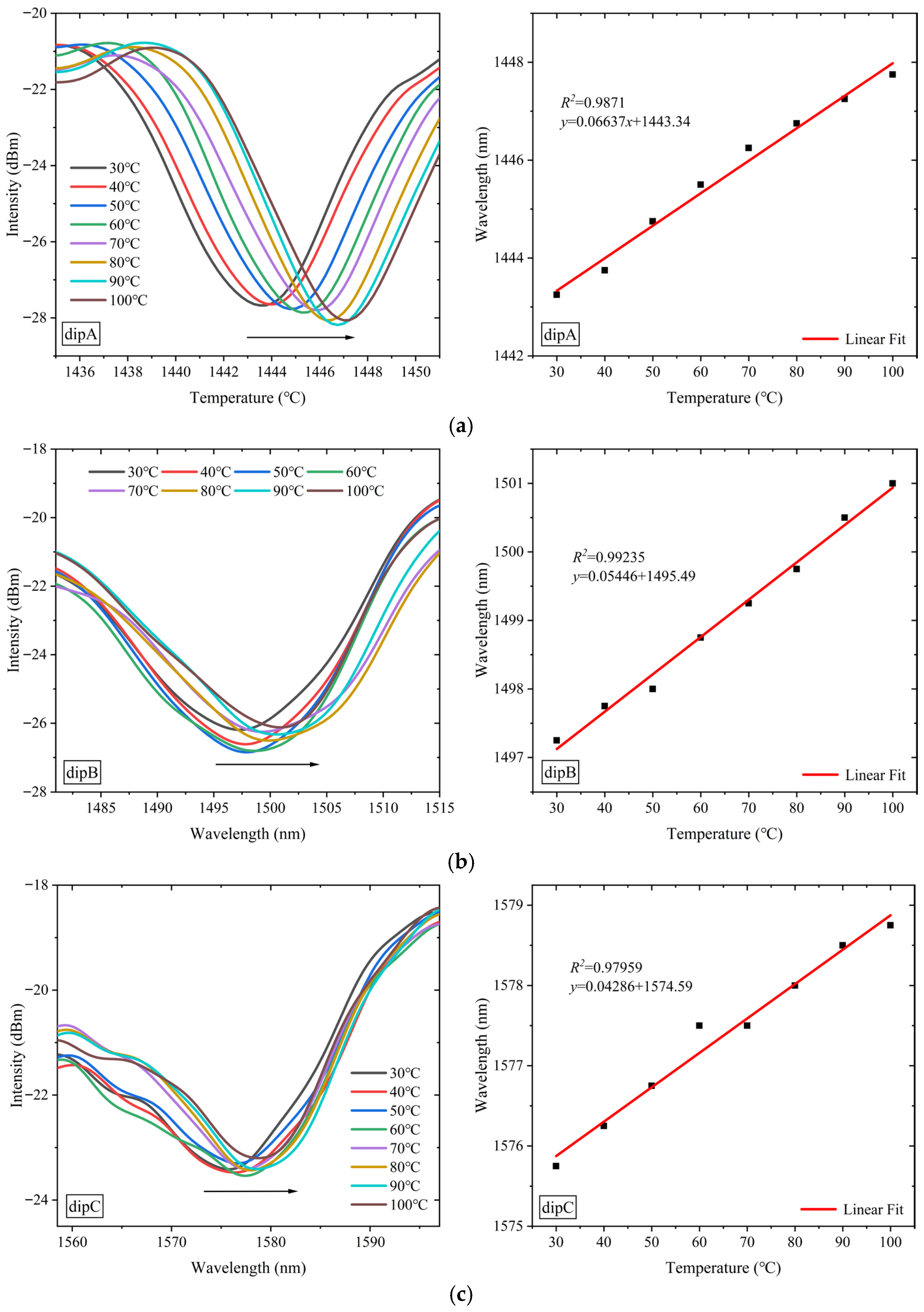

3.1. Results of Temperature Sensing

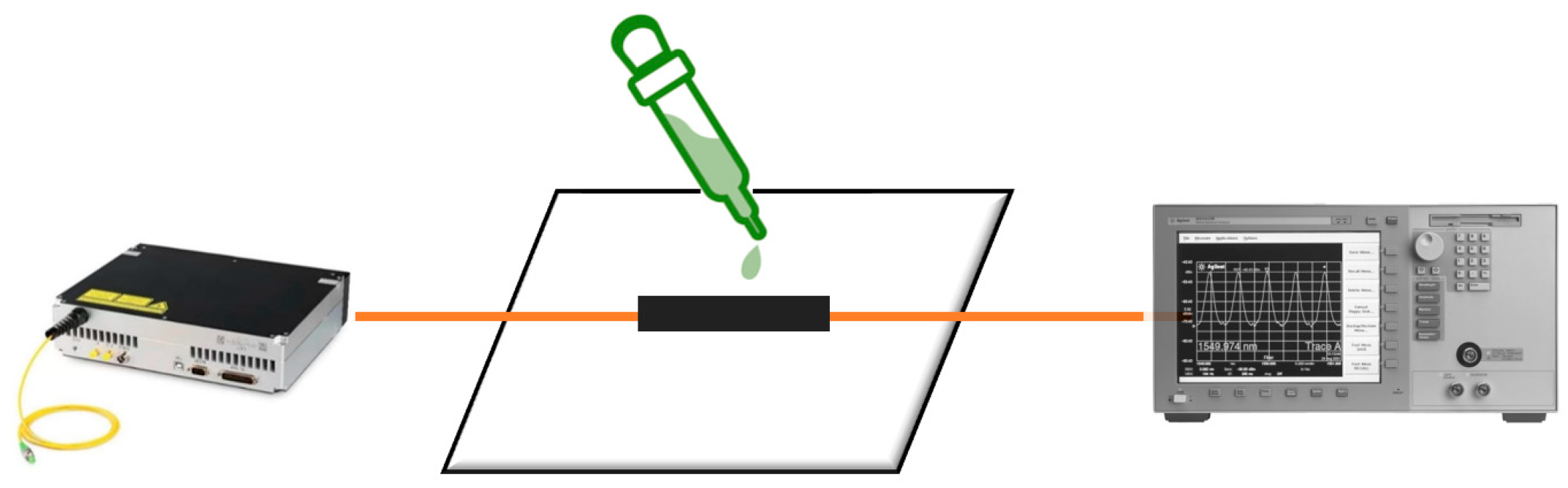

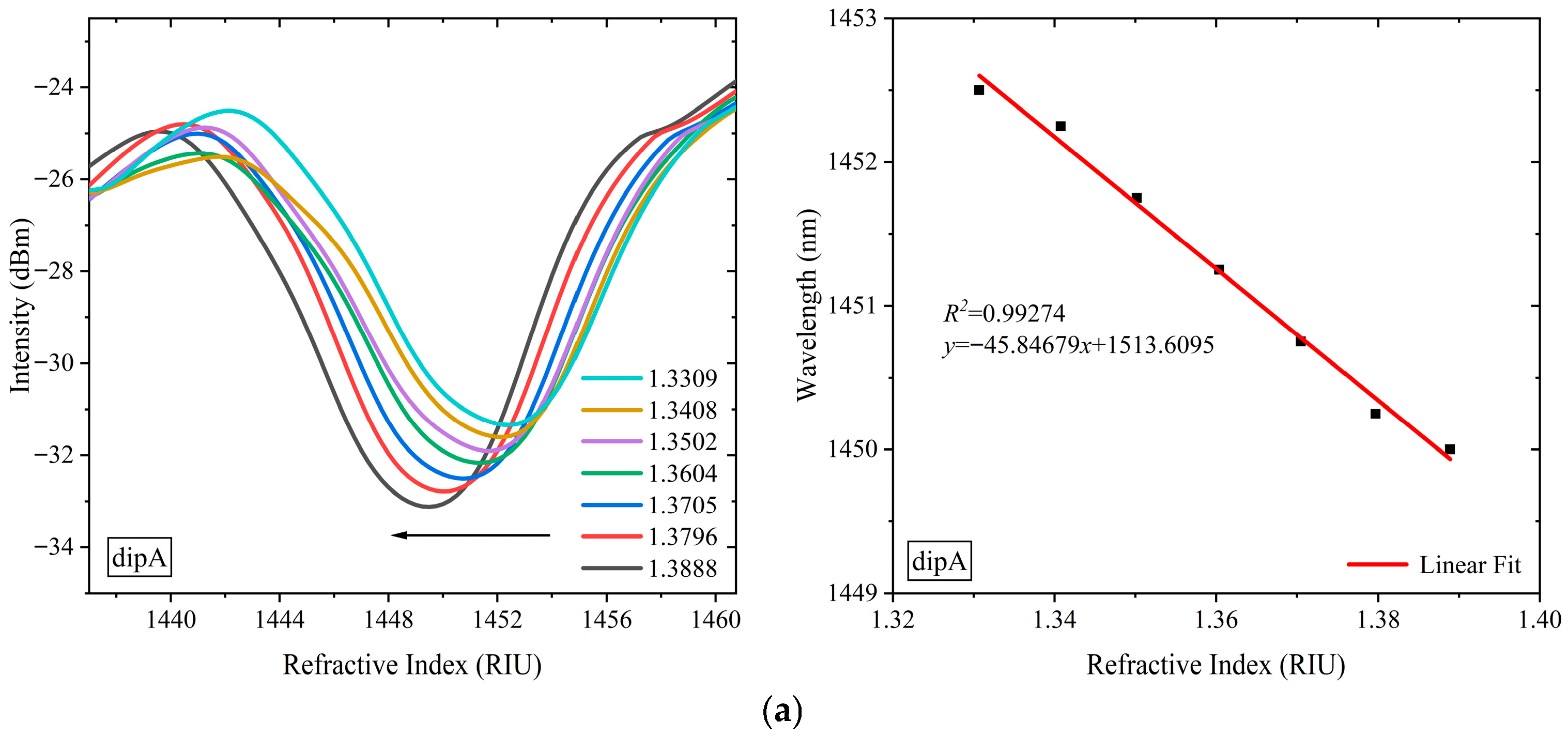

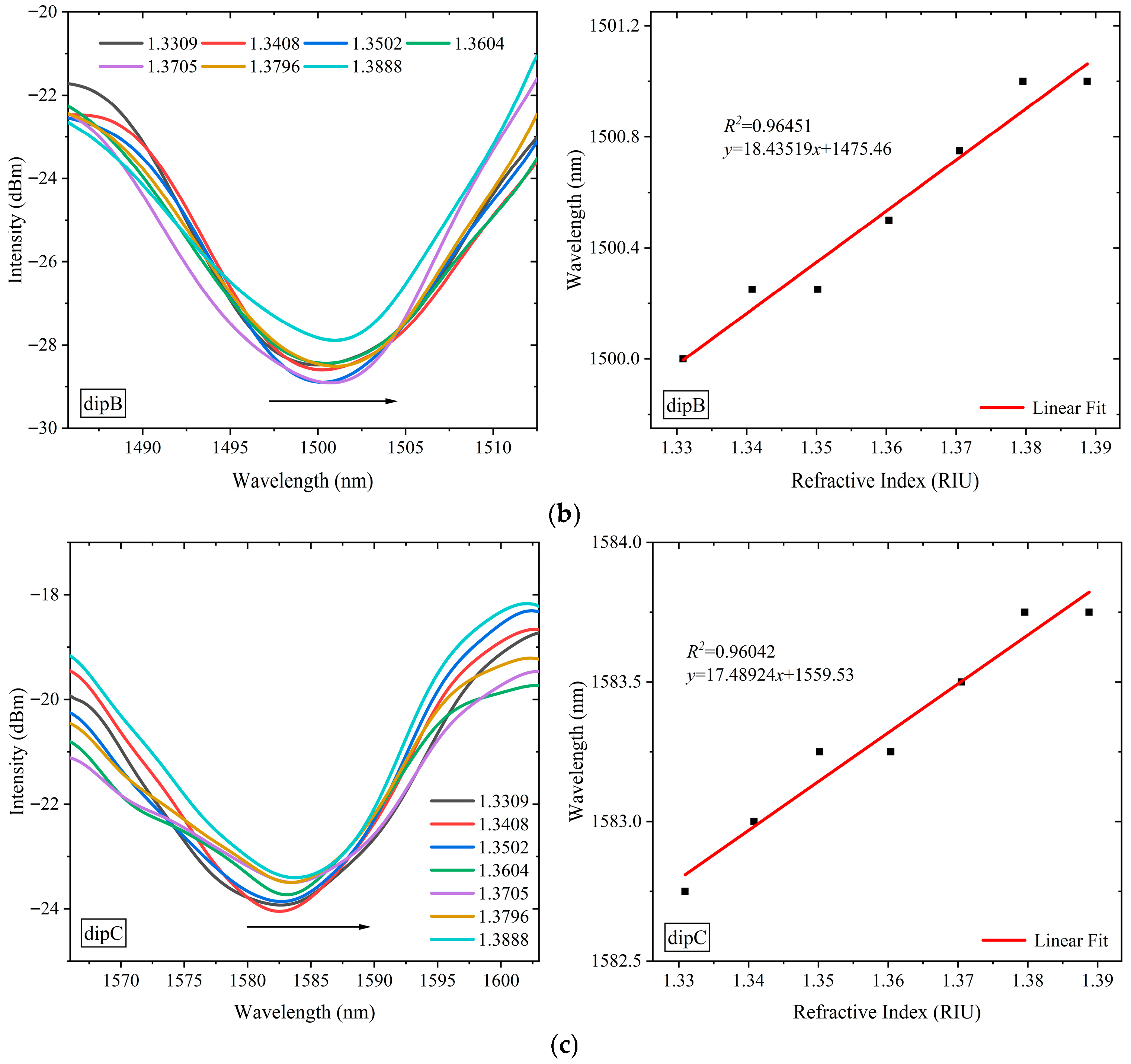

3.2. Results of Refractive Index Sensing

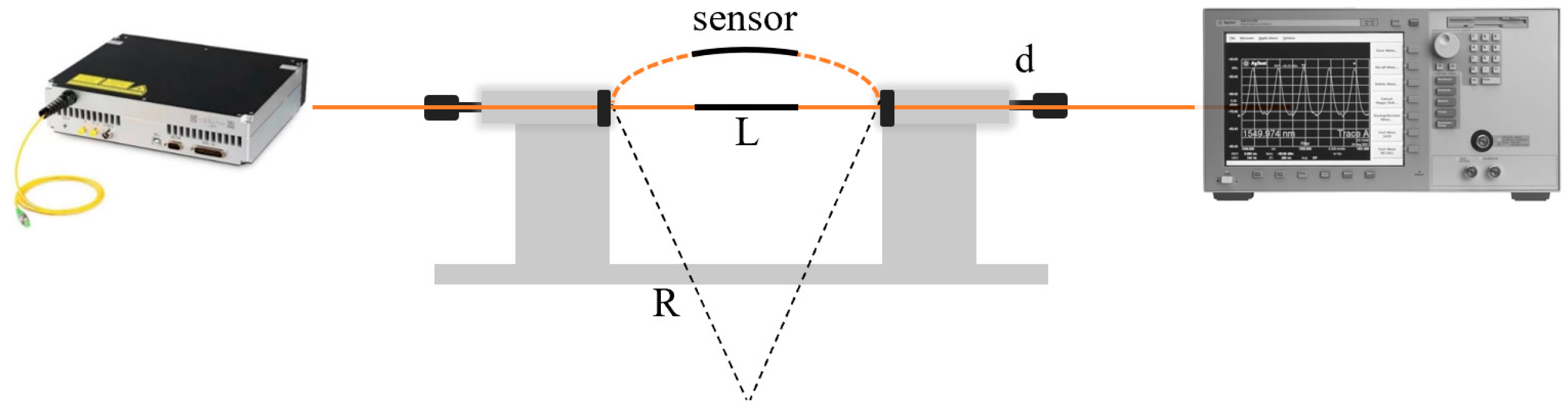

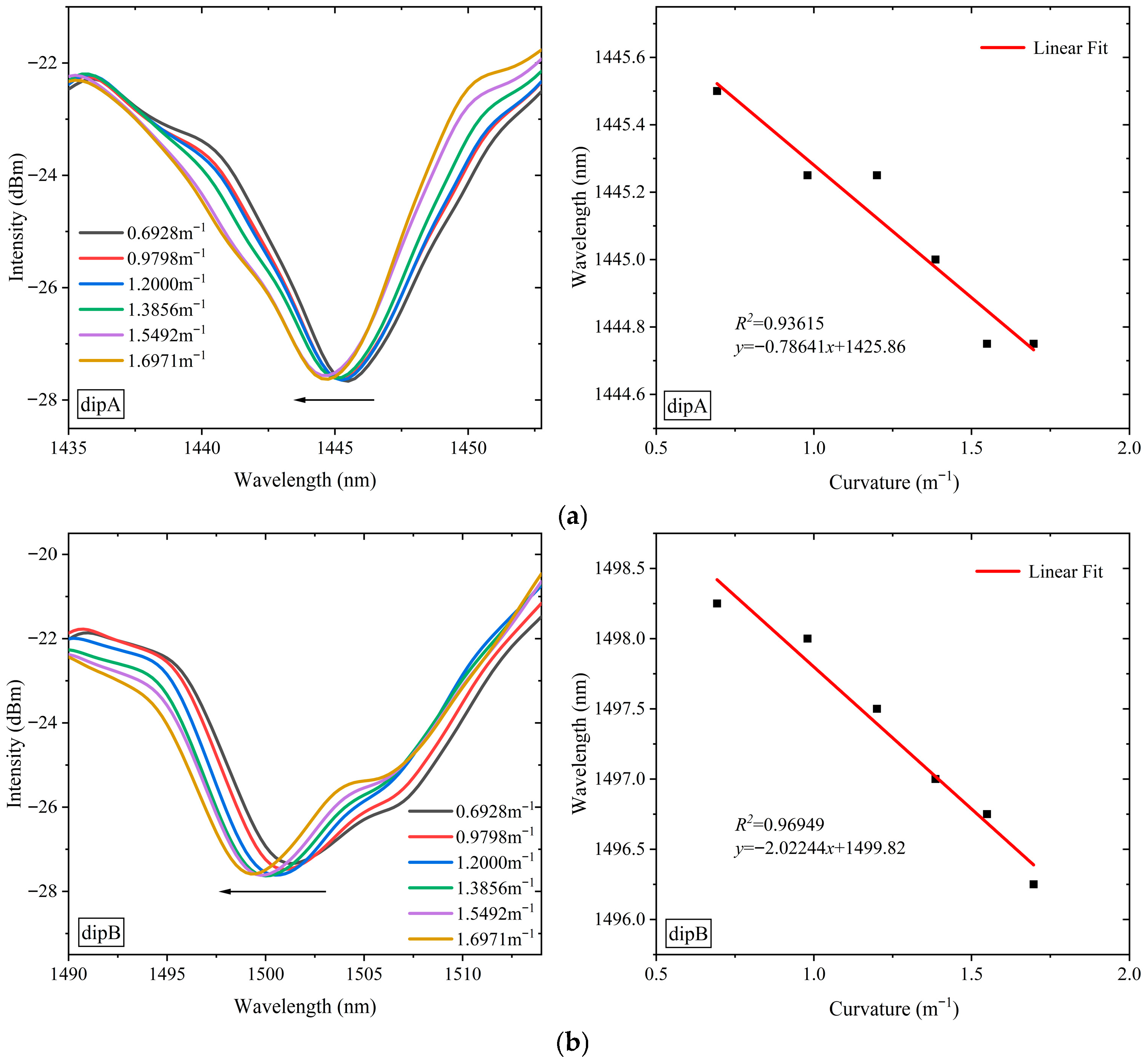

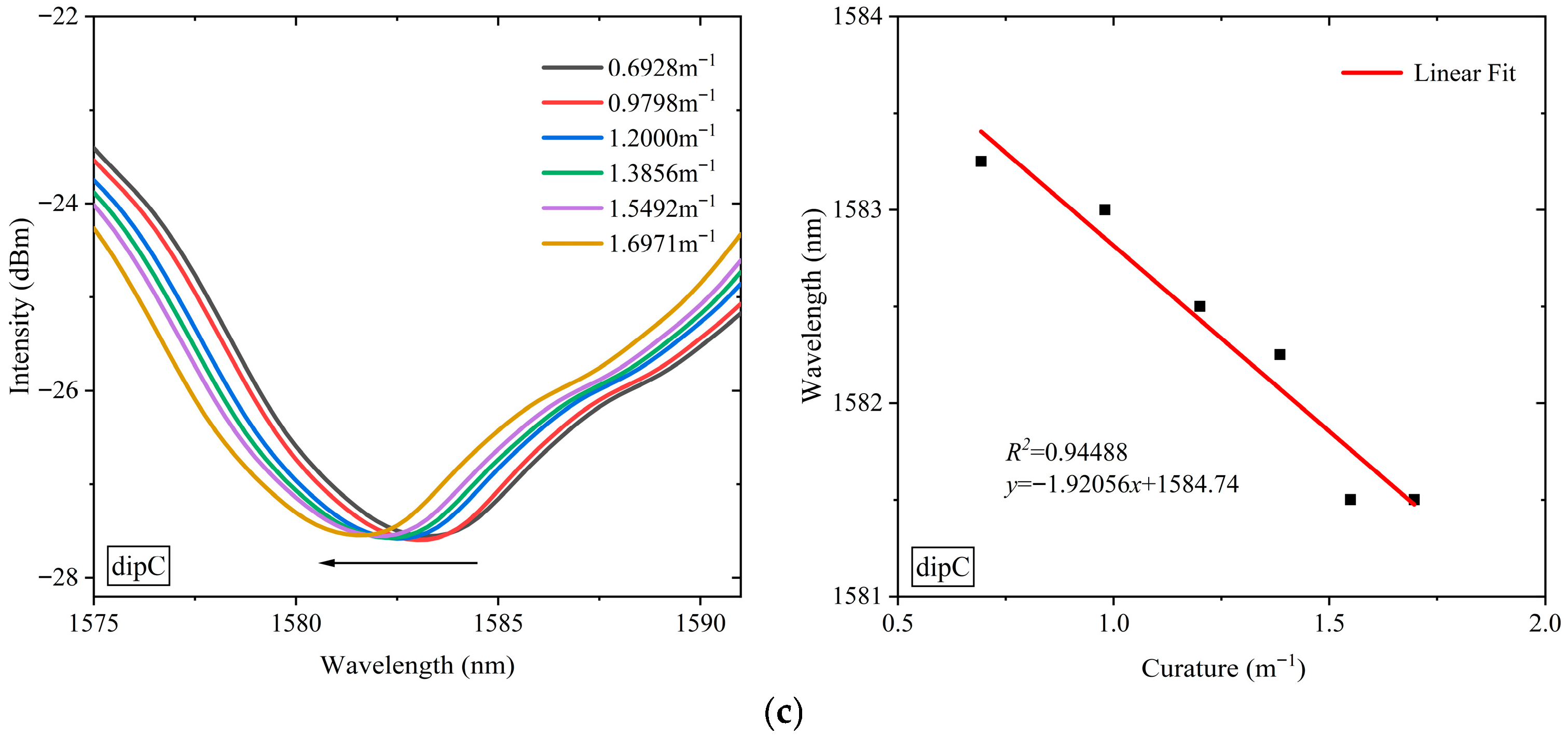

3.3. Results of Curvature Sensing

4. Discussion

4.1. Cross-Sensitivity of the Sensor

4.2. Application Scenarios and Challenges

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Lin, C.; He, X. Functional Optical Fiber Sensors Detecting Imperceptible Physical/Chemical Changes for Smart Batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.Y. Optimizing Multi-Parameter Distributed Fiber Sensors: A Hybrid Rayleigh-Brillouin-Raman System Approach. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.-W.; Wang, Q. Mini Review: Recent Advances in Long Period Fiber Grating Biological and Chemical Sensors. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2019, 47, 140–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Mou, C.; Liu, Y.; He, Z. Multiparameter Sensor Based on Long-Period Grating in Few-Mode Ring-Core Fiber for Vector Curvature and Torsion Measurement. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, C.; Zhu, X.; Wang, P.; Cao, T.; Liu, C.; Sun, S. Simultaneous Humidity and Temperature Measurement Sensor Based on Two Cascaded Long-Period Fiber Gratings. Opt. Commun. 2023, 530, 129137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V. Applications of Long-Period Gratings to Single and Multi-Parameter Sensing. Opt. Express 1999, 4, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Su, H.; Fan, X.; Liu, Y. Few-Mode Fiber-Based Long-Period Fiber Gratings: A Review. J. Opt. Photonics Res. 2024, 1, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Dai, X.; Zou, Q.; Wang, X.; Dai, S.; Zhang, P. Detection of Nickel and Zinc Ions in Aqueous Solution by Phase-Shifted Long Period Fiber Grating Functionalized with Polyacrylic Acid and Chitosan. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Tang, F.; Li, G.; Lin, Z.; Li, H.-N. Long-Period Grating Fiber Optic Sensors Coated With Gold Film and Pulse-Electroplated Iron–Carbon Layer for Reinforcing Steel Corrosion Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tang, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, K.; Fu, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Liao, C.; Lian, J.; Wang, Y. Post-Treatment Techniques for Enhancing Mode-Coupling in Long Period Fiber Gratings Induced by CO2 Laser. Photonic Sens. 2015, 5, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, P.; Zhang, C.; Ni, W.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. Sensing Characterization of Helical Long Period Fiber Grating Fabricated by a Double-Side CO2 Laser in Single-Mode Fiber. IEEE Photonics J. 2019, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Dang, S.; Wang, X.; Zeng, K.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, L.; Du, C. A Highly Sensitive LPFG Torsion Sensor with Step-Index Cladding Modulation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 395, 117041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, R.; Jiang, X.; Teng, C.; Xu, R.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, L. A Long Period Grating Sensor Based on Helical Capillary Optical Fiber. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 4884–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Huang, S.; Qu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y. Ultralow-Duty-Cycle Amplitude-Sampled LPFG Using Deep Tapering and Its Application to Cross-Sensitivity-Free Multiparameter Sensor. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 2321–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Gu, Z.; Ling, Q.; Wang, Y.; Nie, W. Design of an Anti-Temperature Interference Liquid Level Sensor Based on Tilt Long-Period Fiber Grating. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, O.; Huang, Q.; Lei, X. Mechanically Induced Long-Period Fiber Gratings and Applications. Photonics 2024, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tian, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Sensing Characteristics of Helical Long-Period Gratings Written in the Double-Clad Fiber by CO 2 Laser. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 7481–7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Mou, C. Double Cladding Fiber Chiral Long-Period Grating-Based Directional Torsion Sensor. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2019, 31, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, M.; Xiao, R.; Cui, S.; Bai, Y.; Xing, J.; Wang, T.; He, X.; Zhang, S. Triple Parametric Sensor Based on Double-Clad Fiber and Waist-Enlarged Taper Structure. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2024, 88, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Wang, H.; Ze, X.; Wang, S.; Hao, X.; Bai, Y.; Cui, S.; Xing, J.; He, X. A Long-Period Grating Based on Double-Clad Fiber for Multi-Parameter Sensing. Photonics 2025, 12, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121235

Li W, Wang H, Ze X, Wang S, Hao X, Bai Y, Cui S, Xing J, He X. A Long-Period Grating Based on Double-Clad Fiber for Multi-Parameter Sensing. Photonics. 2025; 12(12):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121235

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenchao, Hongye Wang, Xinyan Ze, Shuqin Wang, Xiangwei Hao, Yan Bai, Shuanglong Cui, Jian Xing, and Xuelan He. 2025. "A Long-Period Grating Based on Double-Clad Fiber for Multi-Parameter Sensing" Photonics 12, no. 12: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121235

APA StyleLi, W., Wang, H., Ze, X., Wang, S., Hao, X., Bai, Y., Cui, S., Xing, J., & He, X. (2025). A Long-Period Grating Based on Double-Clad Fiber for Multi-Parameter Sensing. Photonics, 12(12), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12121235