1. Introduction

Free-space optical communication (FSOC) has emerged as a transformative technology for high-bandwidth, low-probability-of-intercept data transmission, with critical applications spanning satellite-to-ground links, secure military communications, and terrestrial last-mile connectivity [

1,

2,

3]. Compared with traditional radio frequency (RF) communications, inter-satellite FSOC links can achieve transmission rates up to two orders of magnitude higher. Despite its unparalleled advantages, FSOC systems are fundamentally limited by atmospheric turbulence—a complex and dynamic phenomenon caused by spatiotemporal fluctuations in the refractive index due to inhomogeneous temperature, pressure, and humidity fields [

4]. These turbulent effects induce severe wavefront distortions, manifesting as beam wander, scintillation, intensity fading, and dynamic phase aberrations, collectively degrading signal fidelity and system performance, severely limiting system bit error rate (BER) and link availability.

Adaptive optics (AO) serves as the cornerstone technology for mitigating such distortions, whether originating from atmospheric turbulence, mechanical vibrations, or optical imperfections, has been widely adopted in FSOC and high-resolution imaging [

5,

6]. However, conventional Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (SHWFS)-based AO systems face inherent limitations in FSOC applications, such as spot fragmentation under strong scintillation [

7,

8]. Under strong scintillation, spot fragmentation impairs centroid estimation accuracy, while low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and multi-channel coupling effects increase wavefront reconstruction errors. Additionally, the hardware complexity of SHWFS-based systems limits their suitability for cost-effective, compact space-to-ground FSOC systems.

To address these challenges, wavefront sensor-less adaptive optics (SLAO) have emerged as a promising alternative that compensates for optical aberrations through iterative optimization of system performance metrics, thereby eliminating the need for direct wavefront measurement [

9,

10]. SLAO inherently exhibits superior robustness against scintillation and low-SNR conditions. Nevertheless, traditional SLAO implementations—particularly those based on stochastic parallel gradient descent (SPGD)—face two major limitations: slow convergence and local optima trapping [

11]. These constraints severely undermine the practical deployment of SLAO in high-speed FSOC systems, underscoring the urgent need for next-generation SLAO algorithms that can satisfy stringent real-time performance requirements while maintaining high accuracy and robustness.

To overcome the aforementioned challenges, various modifications to the SPGD algorithm have been proposed, aiming to accelerate convergence and mitigate the risk of being trapped in local extrema. As the core optimization engine of SLAO, SPGD improvements mainly follow two technical routes: on one hand, incorporating advanced mathematical optimization frameworks—such as Nesterov accelerated gradient (NAG)—to reduce iteration counts and computational overhead; on the other hand, integrating prior knowledge-based optimization, for example, weighted preallocation informed by the statistical properties of Zernike modes.

The Staged SPGD algorithm was developed to enhance convergence speed and stability in large-scale laser coherent beam combining (CBC) systems by Wenhui et al. [

12]. However, the algorithm requires empirical threshold setting for stage transitions, restricting its applicability. An AdamSPGD algorithm that employs adaptive estimation was proposed by Zhang et al. to correct wavefront distortions in coherent FSOC [

13]. However, the high computational complexity limits its deployment in real-time AO systems. The Estimation-based SPGD (ESPGD) algorithm was proposed by Peng et al., which reduces gradient estimation to a single perturbation per iteration via recursive least-squares estimation. This improvement enhances control bandwidth and stability in FSM systems by accelerating convergence and suppressing oscillations [

14]. A method integrating the CoolMomentum into SPGD was proposed by Zhang et al., wherein a simulated annealing–based cooling process dynamically adjusts the momentum coefficient and learning rate, markedly enhancing convergence speed [

15]. A method combining the Sophia optimizer with SPGD was proposed by Chen et al., which utilizes second-order stochastic optimization with momentum and a clipping mechanism to dynamically adjust the update direction and step size, significantly improving both convergence speed and stability under strong turbulence conditions [

16]. Nonetheless, both approaches share common limitations of increased computational burden and sensitivity to initial parameter configurations. In addition, deep learning-based control algorithms have shown considerable potential for enhancing SLAO system performance [

17,

18,

19], providing a new paradigm for SLAO optimization. However, their effectiveness under strong atmospheric turbulence conditions is constrained by the inherent limitations of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), including finite receptive fields, high computational complexity and a lack of physical interpretability. Zhang et al. further demonstrated that neural networks trained with SGD inherently couple task-irrelevant features (e.g., atmospheric speckles in adaptive optics or background pixels in ImageNet) with core predictive features, even when these features are statistically uncorrelated. This feature contamination stems from asymmetric neuron activation patterns during gradient updates, causing irrelevant features to accumulate in weight vectors [

20].

In order to accelerate the convergence speed of SLAO system, we propose a novel modal stage based SPGD which use the Zernike mode coefficients as the optimized variable instead of actuator’s voltage and dynamically adapt the number of optimized modes set and the learning rate according to performance metric to improve the convergence speed. Compared with traditional SPGD, the proposed method performs better in simulation as well as experiment. Compared with AO systems based on SHWFS, the proposed MSSPGD-based SLAO method fundamentally avoids the dependence on accurate spot centroid estimation and wavefront reconstruction, thereby eliminating performance degradation caused by spot fragmentation and low SNR under strong scintillation conditions. Moreover, it significantly simplifies the system hardware, thereby reducing the overall cost, size, and weight of the system. While SHWFS-based AO systems can achieve extremely high restoration accuracy under stable conditions with high signal-to-noise ratios, the algorithm presented in this work offers a more robust and practical alternative for dynamic FSOC links characterized by strong turbulence and platform constraints.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, the basic principles of SPGD algorithm and the proposed modal stage-SPGD (MSSPGD) are introduced. In

Section 3, the phase aberration model in the FSOC system is established, and related simulations and comparisons are conducted to demonstrate the improved performance of the proposed algorithm.

Section 4 presents the experimental validation of the proposed algorithm by analyzing fiber coupling efficiency in the dedicated SLAO system. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the conclusions of the study.

2. Methods

2.1. FSOC System with SLAO

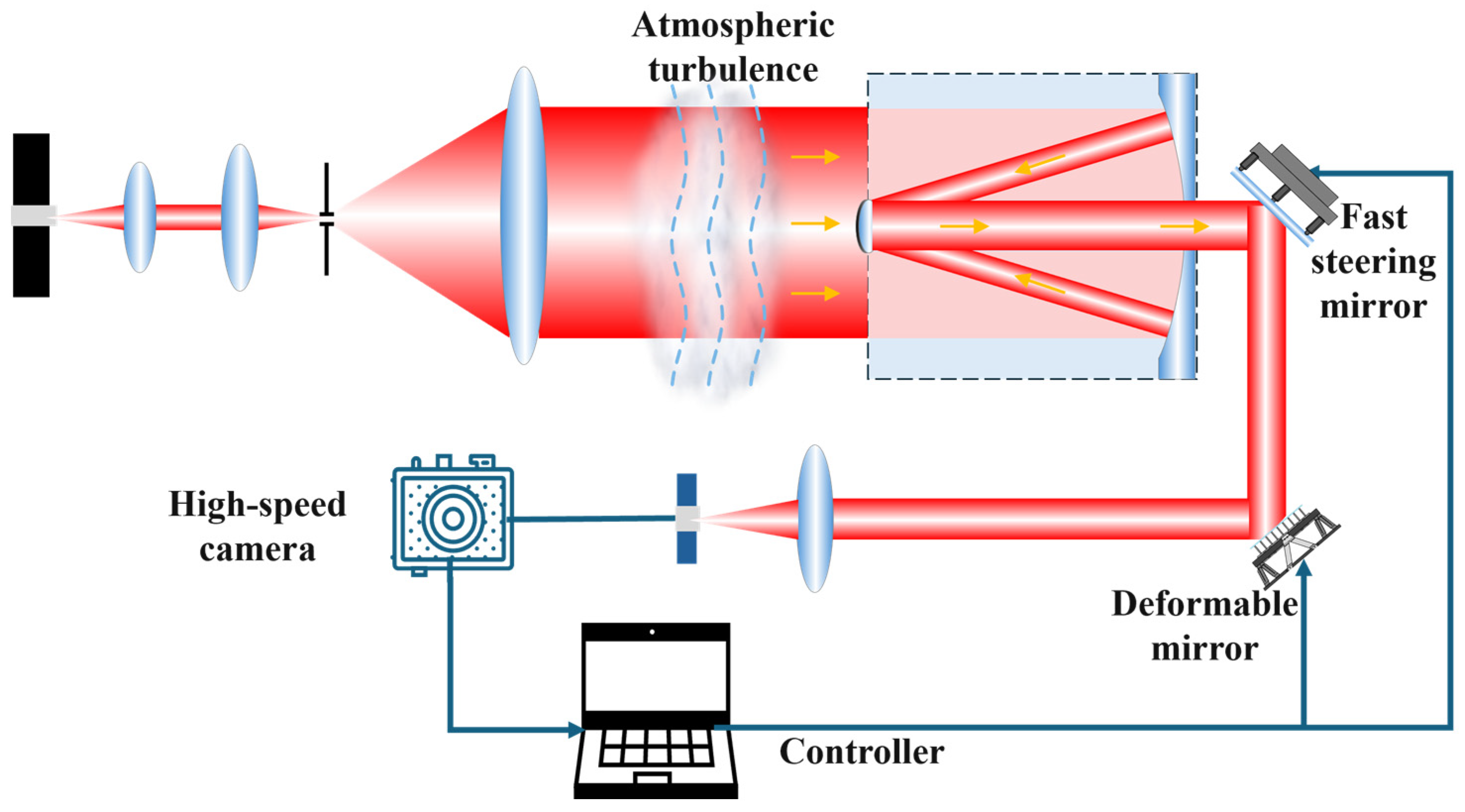

The FSOC system with SLAO operates according to the overall sequence of “channel transmission—turbulence distortion—adaptive correction,” as illustrated in

Figure 1. Specifically, a collimated laser beam first propagates through an atmospheric turbulence channel. The distorted wavefront is then collected by a receiving telescope and directed into the SLAO module (detailed schematic in

Figure 2) for real-time correction.

In SLAO, the incident distorted beam is corrected by a deformable mirror (DM) and then focused onto a high-speed camera through a lens. The wavefront controller generates control signals for the DM based on the detected signal and predefined objective function. Correction proceeds iteratively by applying small perturbations to the DM, evaluating the resulting objective function, and updating the control command according to the chosen optimization algorithm. Through this iterative process, the system converges to an optimal control state that compensates for turbulence-induced wavefront distortions.

2.2. DM Model in SLAO

In this study, a 37-element continuous surface deformable mirror (CSDM) is employed for real-time wavefront correction. The response of the CSDM is commonly characterized by an influence function, which describes the surface deformation induced by the actuation of a single actuator. This influence function is typically modeled using a Gaussian distribution [

21], expressed as:

In this formula, ω denotes the coupling coefficient of adjacent actuators, represents the central coordinates of the actuator, d is the normalized distance between adjacent actuators, and is the Gaussian index, which determines the steepness of the influence function.

The overall wavefront correction achieved by the CSDM is the superposition of the influence function of all actuators, which can be expressed as:

The voltage applied to the actuator is a linear function of the desired surface displacement and is typically constrained within the CSDM’s maximum operational voltage range. This relationship allows precise control of the mirror’s surface shape, thereby facilitating effective correction of optical aberrations.

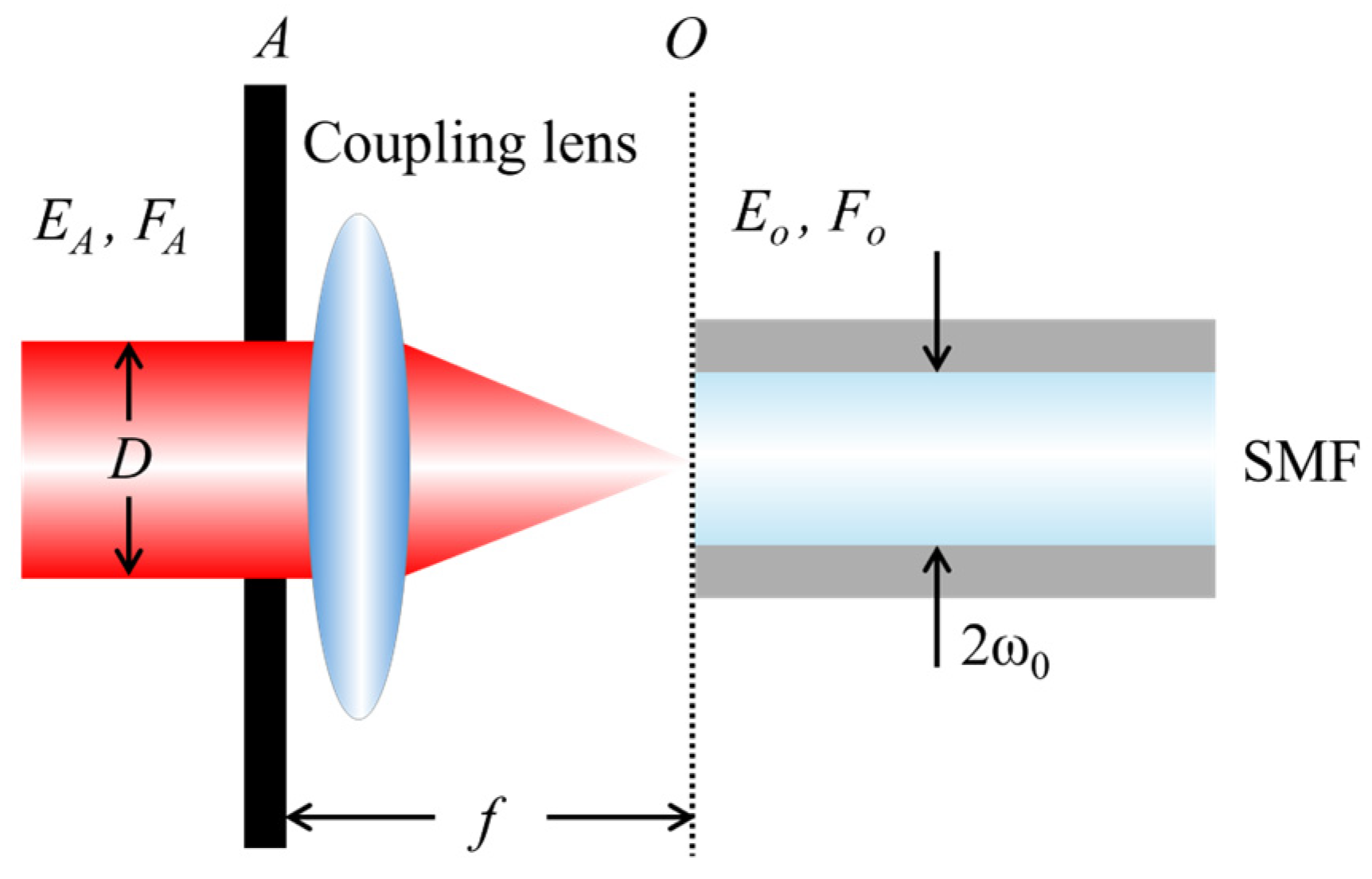

2.3. Theoretical of Fiber Coupling

The fundamental principle of coupling a free-space optical wave into a single-mode fiber (SMF) is field matching [

22,

23], as illustrated in

Figure 3. Given that laser beams in FSOC links typically travel over distances ranging from a few kilometers to hundreds of thousands of kilometers, the beam arriving at the receiver is generally approximated as a plane wave. This incoming beam is then focused by the receiver’s optical system, forming an airy spot on the focal plane.

The coupling efficiency

η of a SMF is defined as

where

denotes the optical field distribution at the fiber end face,

is its complex conjugate, and

represents the mode field of the single-mode fiber.

2.4. Traditional SPGD Algorithm

For a wavefront corrector with

N elements, a far-field image

is obtained after applying control voltages

in SLAO. Here, the mean radius of the intensity distribution measured by the camera is adopted [

15]. This image is then analyzed to derive a performance metric

, which is formulated as a function of the control voltages:

To optimize , the conventional SPGD algorithm for wavefront aberration compensation involves the following steps:

Initially, random small perturbation voltages that follow the Bernoulli distribution are applied to the control voltage of CSDM.

These perturbations have the same magnitude, i.e., , while their signs are randomly chosen with equal probability for and . Specifically, perturbations are first applied to obtain a performance metric , and then perturbations in the opposite direction are applied to obtain an oppositely perturbed performance metric .

Subsequently, the variation of the performance metric

is calculated. The iterative formula for updating the CSDM control voltages is given as:

where

k denotes the iteration number and

γ is a gain coefficient scaling the degree of updates. As the

are updated in the direction of gradient descent, the performance metric

J converges to an extremum after a series of iterations.

Despite the simplicity and ease of implementation, the SPGD method has notable drawbacks. Relying solely on the current update vector, it is susceptible to local optima and exhibits slow convergence in applications with flat gradients or high curvature. To mitigate these issues, efforts must be made to accelerate the iteration process and reduce computational costs.

2.5. Proposed Method

Subspace methods provide an efficient framework for large-scale optimization and have emerged as a key technique in nonlinear optimization, particularly for high-dimensional and computationally demanding problems [

24,

25,

26]. By constructing and solving low-dimensional approximations of the original problem, these methods significantly reduce computational costs per iteration. Leveraging the sparse or structured nature of many large-scale problems, subspace methods efficiently explore the solution space while retaining the essential features of the original problem. Their main advantages include high computational efficiency, broad applicability, strong adaptability, and reliable global convergence guarantees.

Building on the success of subspace methods, we incorporate a dynamic modal stage strategy into the SPGD framework and propose a novel MSSPGD algorithm. Unlike the standard SPGD that operates directly in the full-dimensional control voltage space, MSSPGD performs optimization within an adaptively switching low-dimensional Zernike modal subspace, thereby improving both efficiency and convergence stability. The implementation process is detailed as follows:

Firstly, we define the control subspace using a Zernike modal basis. Set the initial number of modes

, and the maximum allowable mode number

. Then a random perturbation vector is generated within Zernike coefficient domain:

where

denotes the current number of selected Zernike modes in the subspace. Unlike traditional SPGD that applies identical perturbations across the full voltage space, we assign Zernike mode-dependent perturbations based on modes order. Low-order modes receive larger perturbations while high-order modes are down-weighted, yielding faster convergence, reduced noise sensitivity, and improved stability.

Secondly, convert the modal-space perturbation to actuator voltage space:

where

denotes the modal-to-voltage mapping matrix.

Subsequently, apply the perturbations symmetrically around the current voltage vector and evaluate the performance metric for both perturbed states:

Calculate the performance variation

and update the Zernike coefficients using a stochastic gradient-like rule:

If the performance improvement within the current modal subspace reaches a predefined stagnation threshold, the subspace is deemed saturated. The number of Zernike modes, , is then updated to define a new, expanded subspace, and a new optimization iteration begins. Furthermore, the gain coefficient is adaptively tuned across different convergence stages: a larger gain is employed during the early exploration phase to accelerate convergence and escape shallow local minima, while a smaller gain is used in the later stage to refine the solution and achieve high-precision optimization.

Specifically, the algorithm introduces a convergence stagnation detection mechanism to dynamically trigger subspace expansion. A sliding window with length

W is employed to continuously monitor changes in the performance metric

. The mathematical definition of the stagnation criterion is as follows: at the

k-th iteration (

k > 20), the arithmetic mean of the changes

in the performance metric within the window is calculated as:

The quantifies the convergence rate over the most recent W iterations. When this value falls below a predetermined positive stagnation threshold (), the algorithm determines that the current optimization process has stagnated on a local plateau. At this stage, the number of Zernike modes is expanded from the initial to . The purpose of this design is to enable the algorithm to exploit a low-dimensional space for rapid exploration in the early stage, while later escaping local optima through dimensionality elevation and reducing oscillations near the optimal solution, thereby achieving an adaptive balance between coarse and fine search.

The implementation of the MSSPGD algorithm for SLAO is comprehensively described in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. The procedure of the MSSPGD algorithm |

Input: The initial and final number of Zernike modes ,, the learning rate , the initial and final amplitudes of random perturbation applied to the modal coefficients , and the maximal number of iterations N.

Output: Calculated the control voltage vectors of CSDM .

1: Initialize control voltage vectors of CSDM and the desired convergence point

2: for k = 1,…,N do

3: Randomly generate the perturbed modal coefficients

4: Project the perturbed modal coefficients into the control voltage space

5: Evaluate the objective functions under perturbation voltage

6: Compute the performance change and (k > 20)

7: Update the perturbed modal coefficients

8: If or > 0.4 (experience selection value)

Adapt the number of Zernike modal according to

Update the learning rate and perturbation amplitude.

end if

9: Check the termination condition: if or , then stop.

10: end for |

Theoretically, the proposed MSSPGD method enhances the convergence efficiency and robustness of classical SPGD by incorporating Zernike modal subspace. In particular, projecting the control vector into a low-dimensional Zernike space reduces the degrees of freedom of the optimization problem, while the adjustment of active modes based on real-time performance further accelerates convergence and strengthens robustness against local optima.

3. Simulations

All numerical simulations in this paper are conducted following the closed-loop feedback framework detailed in

Section 2.5 and Algorithm 1, to accurately emulate the real-time correction process in the SLAO system. Atmospheric turbulence modeling is realized using the PWD algorithm, which combines the random sampling concept based on the Sparse Spectrum (SS) technique with the computational efficiency of the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). Different turbulence strength scenarios are constructed by adjusting the receiver system aperture diameter

D and the atmospheric coherence length

. The simulation turbulence parameters are listed in

Table 1 as follows:

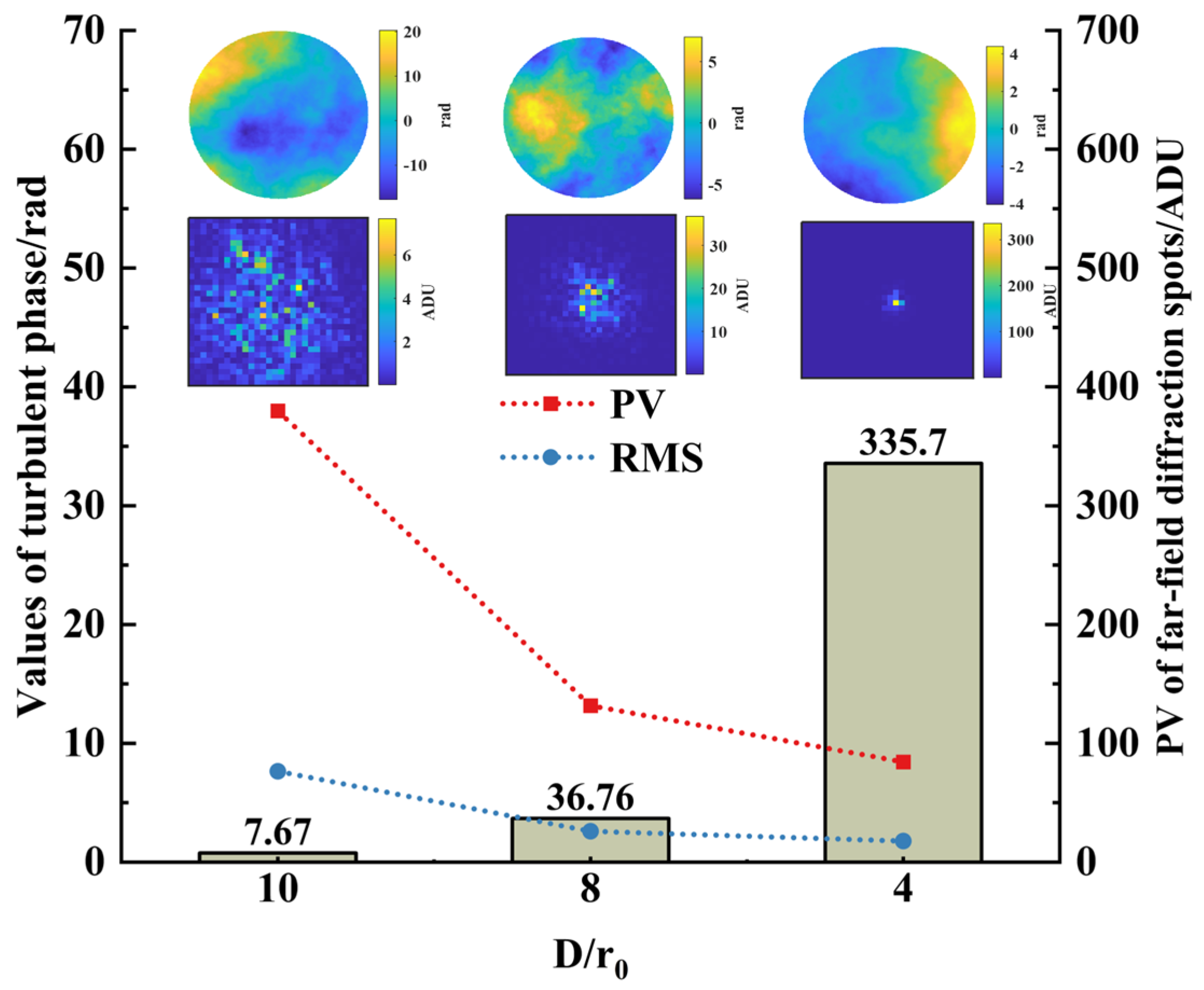

Using a 1024 × 1024 sampling grid with an aperture diameter of

D = 1 m, three sets of phase screens corresponding to decreasing turbulence intensities are generated by setting

= 0.25 m, 0.125 m, and 0.1 m, respectively. The corresponding far-field diffraction patterns are shown in

Figure 4, clearly demonstrating the impact of turbulence strength on beam quality.

When = 0.1 m, the phase distribution exhibits significant spatial fluctuations, with energy dispersed into multiple isolated speckles. The diffraction ring structure is completely destroyed, and the spot centroid is notably shifted, indicating severe pointing errors caused by strong turbulence. As increases to 0.125 m, the energy partially converges toward the central region but still shows asymmetric aberrations, implying that mid-order aberrations—such as coma—still dominate the wavefront distortion. When further increases to 0.25 m, the phase fluctuations and gradient distribution become smoother, and the energy is highly concentrated in the central bright spot, with the peak value of the corresponding far-field diffraction pattern increasing by nearly an order of magnitude.

Figure 4 also provides a quantitative analysis of the system’s performance under different turbulence conditions. Specifically, it presents the Peak-to-Valley (PV) and Root Mean Square (RMS) values of the turbulence-induced phase distortions. These metrics quantitatively demonstrate the correlation between turbulence-induced phase aberrations and turbulence intensity. As shown in the figure, as

decreases from 10 to 4, both the PV and RMS values of the turbulent phase monotonically decrease, precisely corresponding to gradual reduction in phase fluctuation severity observed in the phase maps. The diffracted speckle energy gradually concentrates, consistent with the physical principle described by Kolmogorov turbulence theory that phase variance positively correlates with

.

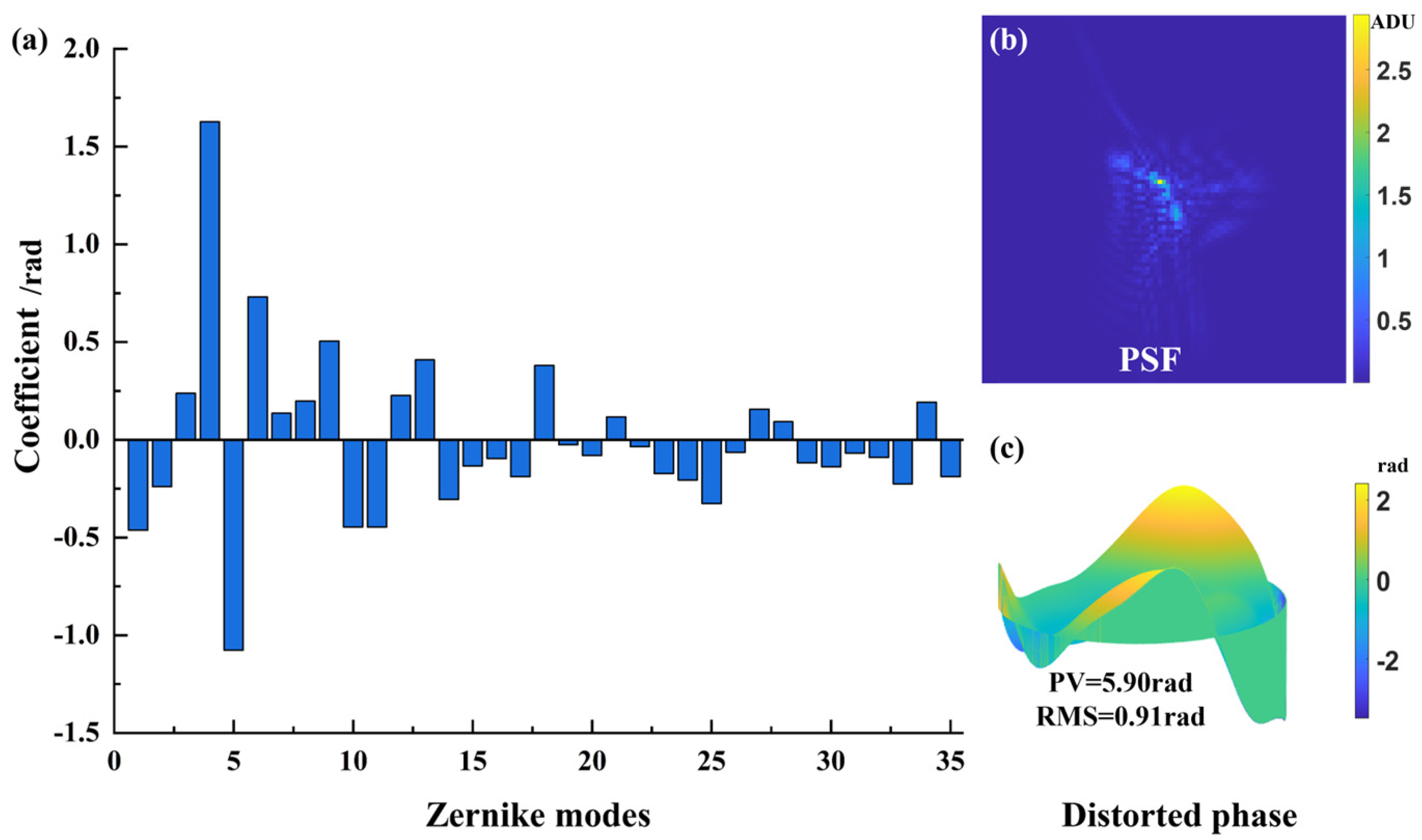

Figure 5 displays a typical single-frame wavefront and its corresponding point spread function (PSF) randomly sampled from the generated turbulence simulation dataset.

Figure 5a shows the Zernike polynomial coefficients for the first 35 orders corresponding to the wavefront. The results indicate that low-order aberrations (such as tilt, defocus, and astigmatism) dominate the wavefront distortion under the generated turbulence, with their coefficient amplitudes being significantly higher than those of higher-order aberrations.

Figure 5b shows the corresponding point spread function, exhibiting significant spot broadening and asymmetric shapes induced by turbulence, which further confirms the significant impact of low-order aberrations on image quality.

Figure 5c presents the phase distribution of this wavefront frame, which is highly consistent with the quantitative analysis of the Zernike coefficients. Since low-order aberrations dominate the turbulence wavefront, MSSPGD initially applies a coarse optimization based on low-order Zernike modes to accelerate convergence and effectively capture the main wavefront distortion features, followed by fine-tuning using higher-order modes to enhance correction accuracy. The turbulence phase characteristics demonstrated in

Figure 5 offer theoretical support for the design of the MSSPGD algorithm proposed in this study.

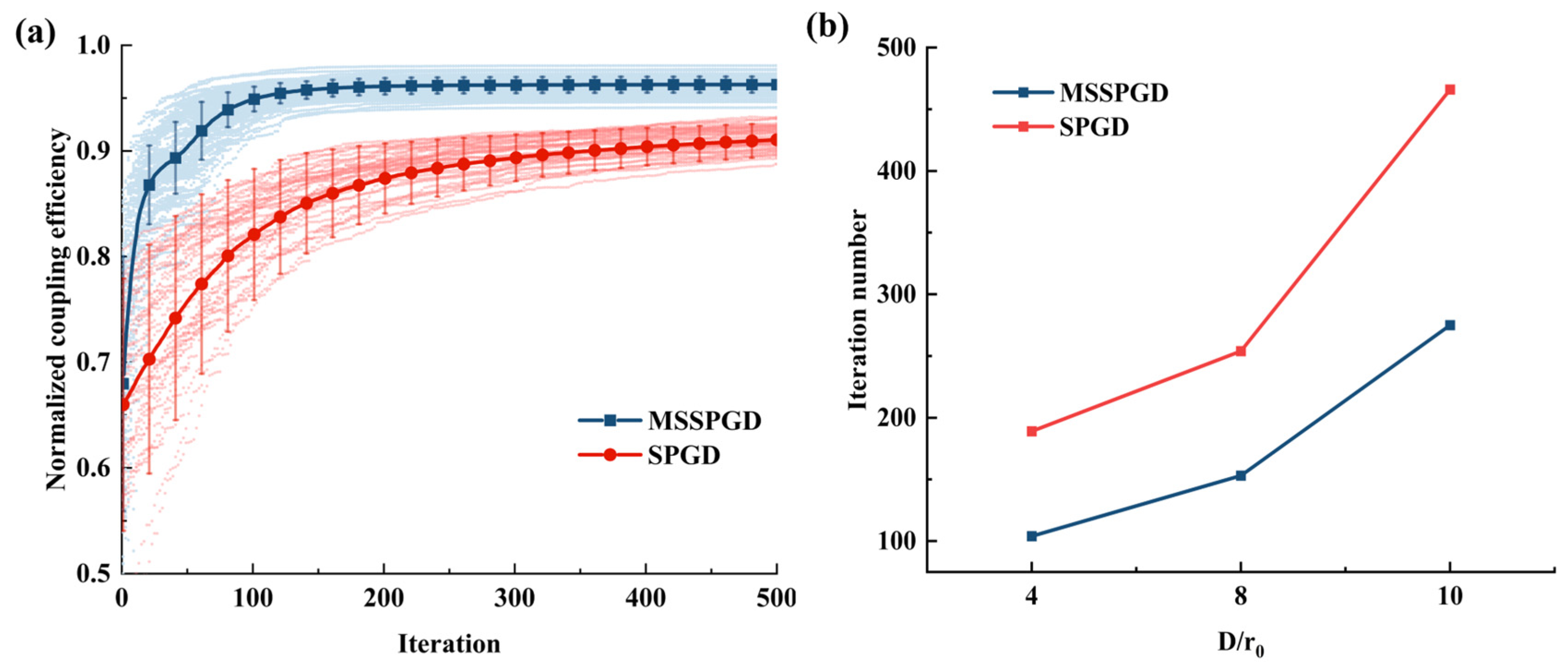

We conducted a comparative evaluation of the correction performance between the proposed algorithm and the conventional SPGD algorithm under the turbulence condition of

D/

r0 = 4. The convergence trajectories under 100 independent turbulence phase realizations are illustrated in

Figure 6a. Although the SPGD algorithm ultimately attains convergence, its progression is markedly protracted. This inefficiency primarily stems from the algorithm’s indiscriminate application of random perturbations across the entire control space. In high-dimensional solution spaces, such an undifferentiated search strategy with a fixed step size resembles a blind trial-and-error process, resulting in extensive computational resources being expended on high-order aberrations that contribute marginally to wavefront correction. This directly translates into an elongated convergence period.

In contrast, the MSSPGD exhibits a markedly faster convergence, reaching a η above 0.95 in fewer iterations, followed by stable performance. This pronounced acceleration is chiefly attributable to its mode-switching mechanism. During the initial phase—when the normalized η remains below 0.9 (a threshold adaptively adjusted based on turbulence intensity)—the algorithm selectively corrects the first seven Zernike modes. This targeted strategy effectively compensates for the low-order aberrations that dominate the initial wavefront distortions, thereby facilitating swift optimization within a reduced-dimensional subspace and significantly expediting initial convergence. Subsequently, upon detecting a stagnation in η improvement, the algorithm transitions to a refinement stage, adaptively expanding the search space to include 25 modes while simultaneously halving the perturbation amplitude. This strategy enables fine-tuned adjustments of residual high-order aberrations that remain after the initial coarse search, thereby circumventing the precision limitations imposed by exclusive low-order mode correction and ultimately achieving a higher overall correction accuracy than the traditional SPGD approach.

To assess the algorithms’ robustness across varying turbulence intensities,

Figure 6b presents the mean number of iterations required to reach convergence under different

conditions, with each dataset derived from 100 independent turbulence realizations. The results clearly indicate that turbulence strength significantly affects convergence speed. As

increases, the correction difficulty rises, leading to a corresponding increase in the number of iterations needed for convergence, as evident in

Figure 6b.

Notwithstanding these challenges, MSSPGD consistently outperforms the conventional SPGD algorithm across diverse turbulence intensities, demonstrating superior capability for rapid initialization under different conditions. These simulation results substantiate the efficacy of the MSSPGD algorithm.

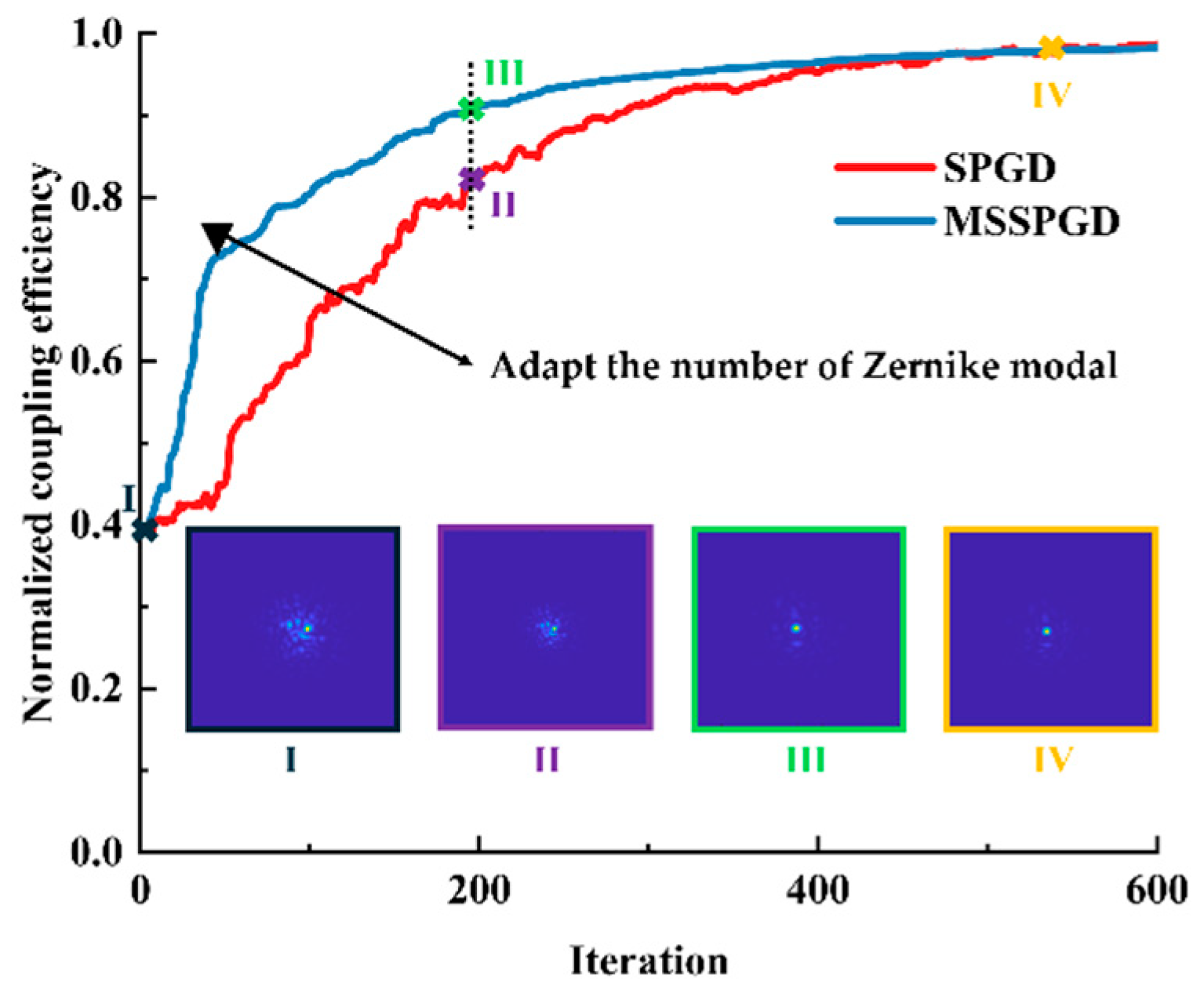

To provide a more intuitive comparison of the correction process and performance differences between the SPGD and MSSPGD algorithms,

Figure 7 presents the simulated far-field spot patterns of both algorithms during the iteration process. At 200 iterations, the conventional SPGD algorithm’s far-field spot still appears as a diffuse pattern composed of multiple speckles, with scattered energy and no distinct central bright spot formed. In contrast, the MSSPGD algorithm rapidly achieves energy concentration at the same number of iterations, significantly improving spot quality, with a sharper and brighter central spot, attaining an excellent correction effect nearly equivalent to that of the traditional SPGD algorithm at 543 iterations and close to the diffraction limit.

To ensure a rigorous and clear comparison, all simulation comparisons involving the SPGD algorithm in the above text were conducted with a learning rate

γ = 1. This value was determined through preliminary simulations and proven to be optimal over a dataset of 3 × 1000 frames of turbulence data. The perturbation amplitude

Δu was set to 0.1 μm using the same selection strategy. These parameter choices ensure that the SPGD algorithm is evaluated under its optimal conditions when compared to the MSSPGD algorithm.

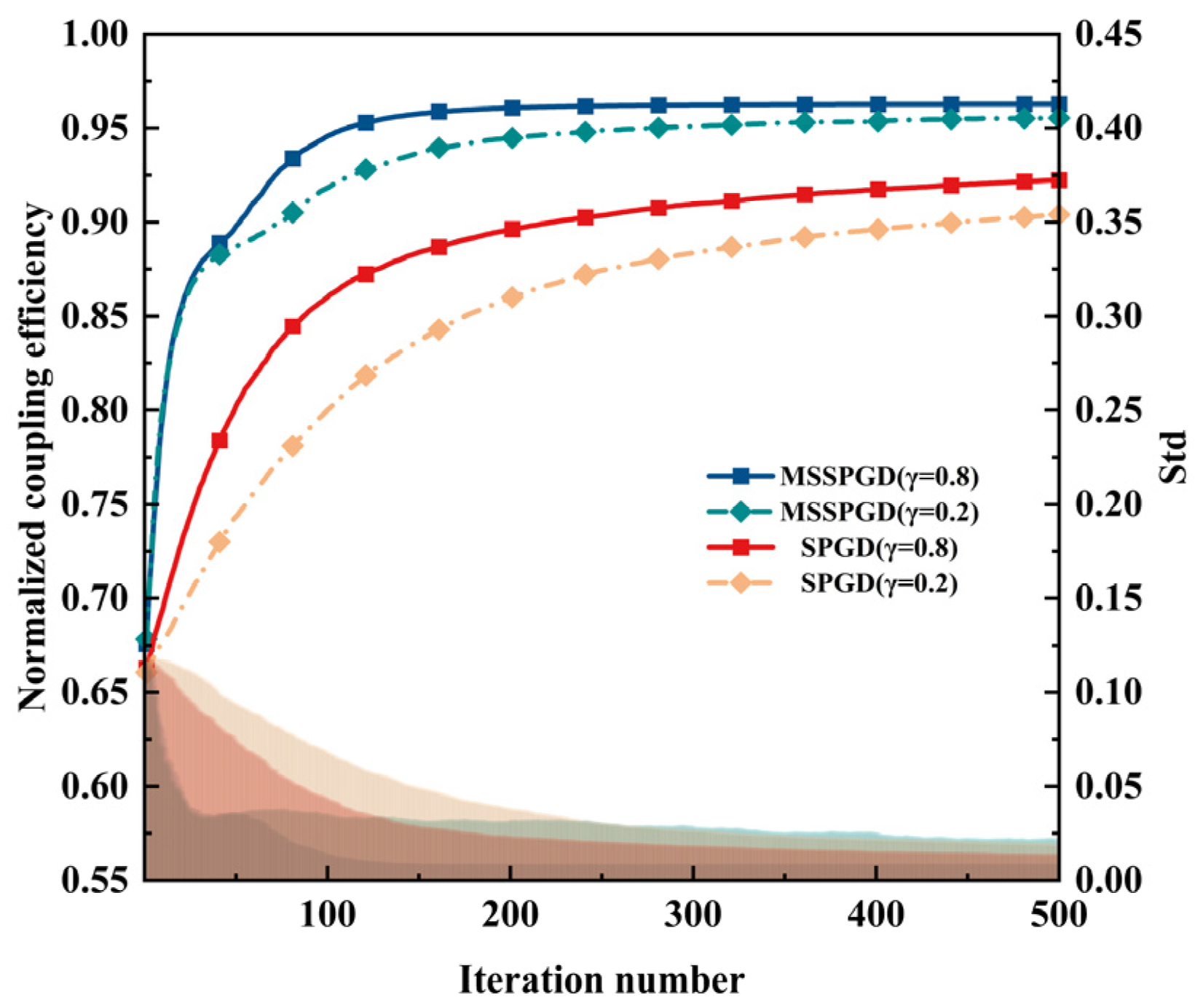

Figure 8 illustrates a comparative analysis of the convergence performance between the SPGD and MSSPGD algorithms under varying learning rate. When the learning rate is set to

γ = 0.2, the SPGD algorithm exhibits a noticeably reduced convergence speed and fails to achieve effective correction within a finite number of iterations. Conversely, with a higher learning rate of

γ = 0.8, the SPGD algorithm demonstrates an improvement in initial convergence speed relative to the low learning rate case; however, both its final correction accuracy and overall convergence velocity remain significantly inferior to those of the MSSPGD algorithm. This outcome underscores the practical limitations of parameter tuning inherent to the traditional SPGD algorithm. In contrast, the MSSPGD algorithm manifests a high degree of robustness across different initial learning rates. Benefiting from its staged optimization strategy, even under a low learning rate (

γ = 0.2), rapidly searching within the reduced-dimensional mode space ensures both satisfactory convergence speed and final performance. Under a higher learning rate (

γ = 0.8), the algorithm’s pre-configured refinement phase, which halves the learning rate, effectively suppresses oscillations near the optimum, enabling swift convergence and stable attainment of a superior performance plateau.

4. Experiment

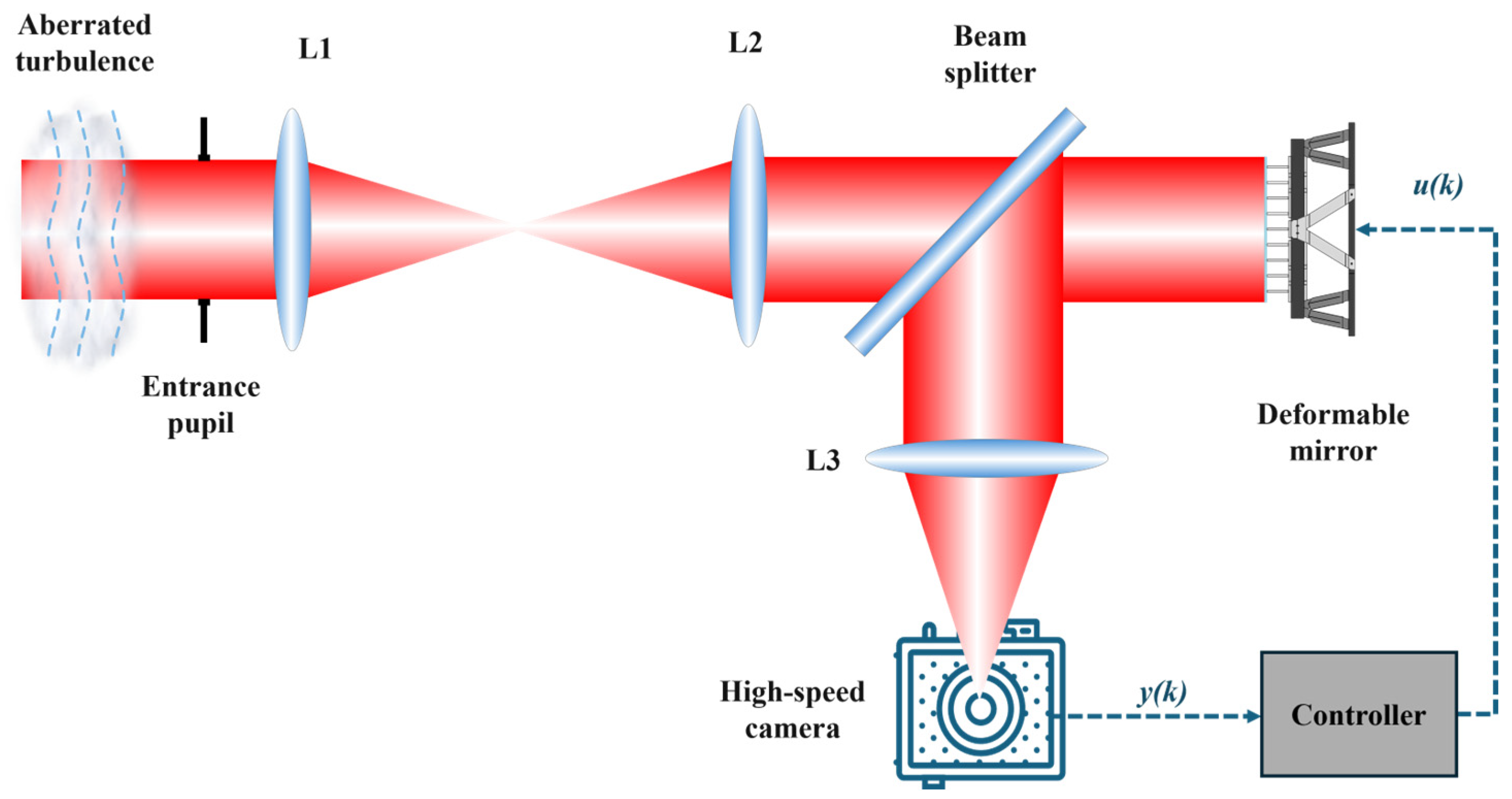

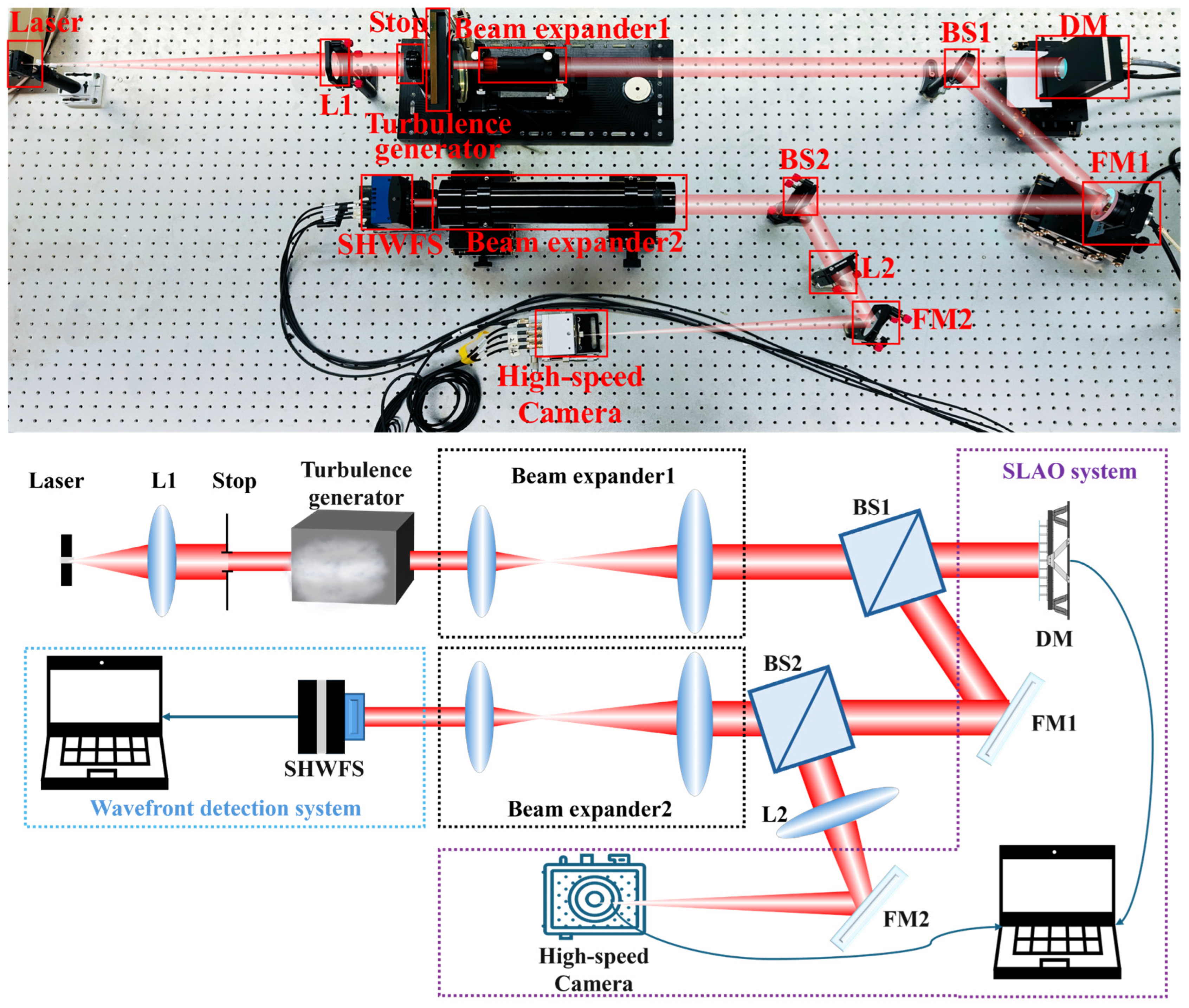

We established an experimental platform for turbulence adaptive optics, with the optical schematic shown in

Figure 9. Employing a modular design, the system achieves full-link beam control and correction, comprising four core units: a laser source and collimation unit, a turbulence simulation unit, a beam control unit, and a SLAO correction unit.

A He-Ne laser source (λ = 633 nm) emits a beam that is shaped into collimated light by lens L1 (focal length = 600 mm). This collimated beam enters the turbulence simulation unit. This unit utilizes a custom rotating phase screen (r0 = 0.6 mm @ 633 nm, made by Lexitek, Watertown, MA, USA) to simulate realistic atmospheric transmission environments, with its phase distribution conforming to Kolmogorov statistics. A precision adjustable aperture stop controls the beam size transmitted through the phase screen to 3.5 mm, establishing a benchmark test environment with specified turbulence strength D/r0 is about 6. The turbulence-modulated distorted beam then enters a 10× beam expander (GBE10-A, Thorlab, Newton, NJ, USA). The beam expander expands the beam diameter incident on the deformable mirror (DM) to 35 mm. The expanded beam is split by beam splitters BS1 and BS2, with 25% of the optical power directed to a high-speed camera (Cyclone-1HS-3500 CXP-12, sampling rate 100 Hz, Optronis, Kehl, Germany). The intensity distribution data captured by the camera is processed in real-time by a wavefront processing computer using a modal stage SPGD algorithm to calculate the control commands to drive the DM, compensating the turbulence-induced phase distortion in the signal path. This establishes a closed-loop, wavefront sensor-less control architecture of “intensity acquisition—iterative algorithm computation—DM response”. The experiment employed a self-developed 37-element piezoelectric DM as the wavefront corrector, with actuators arranged in a closely packed square grid at a pitch of 5 mm, and an effective clear aperture of 35 mm. The intrinsic frequency response of the DM exceeds 10 kHz, enabling the correction of rapidly varying, small-scale wavefront aberrations. However, in the current experimental setup, the self-developed digital-to-analog conversion (DAC) module that generates the control voltage introduces a significant data transmission delay of 2 ms. As a result, the DAC-induced delay, rather than the mechanical response of the deformable mirror, become the primary bottleneck limiting the overall closed-loop correction rate.

To objectively evaluate the system’s correction performance, the beam corrected by the DM undergoes secondary beam splitting via beam splitter BS2. It is then coupled precisely into a Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor (SHWFS) via the M6_SH beam reducer (reduction ratio 10:1), adjusting the beam diameter from 35 mm to 3.5 mm. The SHWFS photodetector (EoSens 1.1CXP2, Mikrotron, Munich, Germany) features a square microlens array with 89 valid subapertures. Each subaperture covers 28 × 28 pixels, with a microlens pitch of 383.6 µm and focal length is 16.255 mm. The SHWFS measurements and corrections provide an ideal airy disk far field image for calculating the Strehl ratio, which is equivalent to the coupling efficiency and thus serves as a performance metric for analysis.

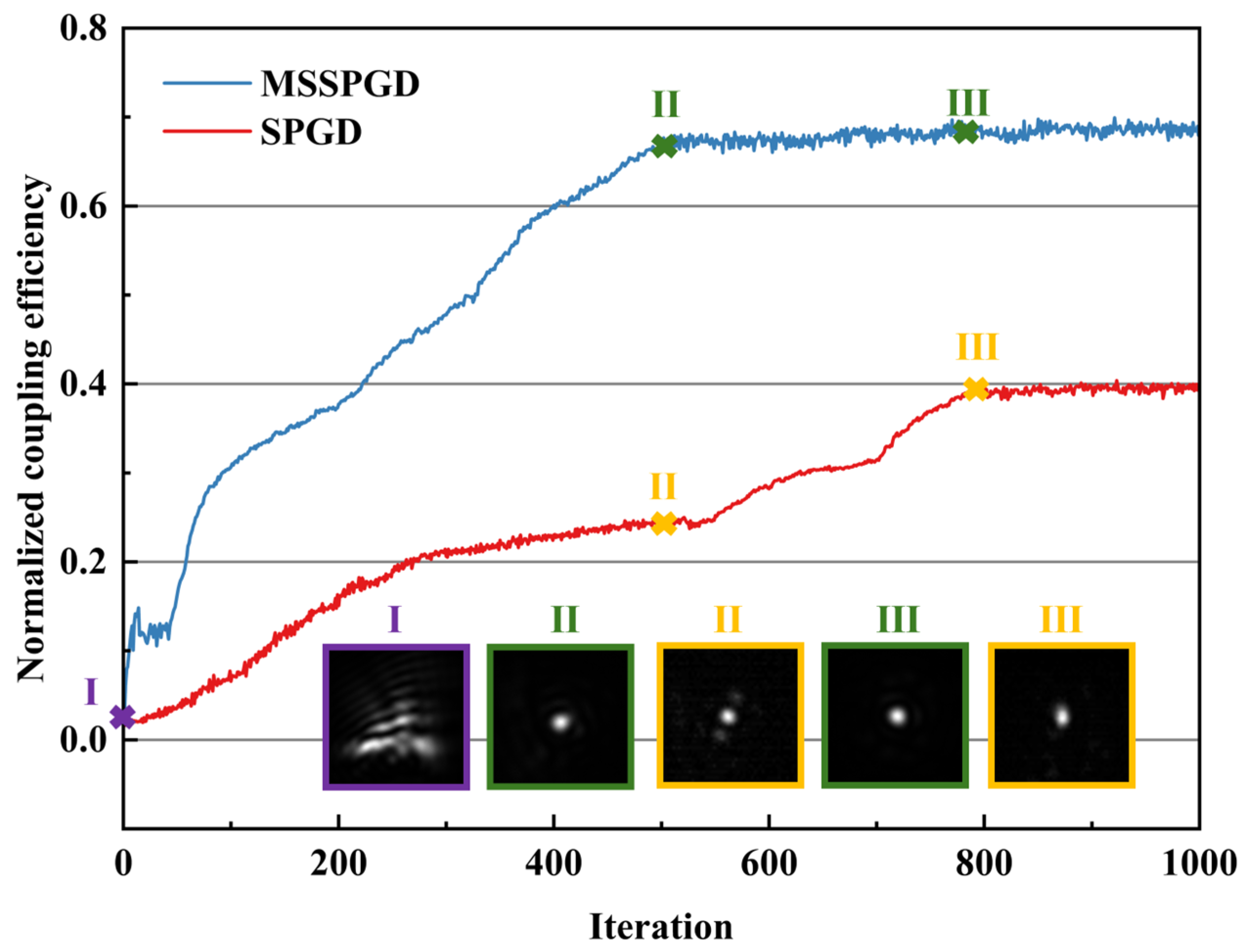

Figure 10 illustrates a comparative analysis of coupling efficiency between two algorithms under turbulence conditions with

D/

r0 = 6. The convergence curve of the conventional SPGD algorithm reveals a persistently slow increase in coupling efficiency throughout the iterative process, ultimately converging to approximately

η = 0.4 after 800 iterations. This convergence behavior stems from the SPGD algorithm’s fixed perturbation strategy applied across the full modal space; its indiscriminate search mechanism results in substantial computational resources being expended on high-order mode exploration, preventing rapid convergence within a short timeframe. In contrast, the MSSPGD algorithm demonstrates a rapid rise in coupling efficiency during the initial iterations, achieving convergence beyond

η = 0.8 within about 600 iterations. The convergence curve of the MSSPGD algorithm exhibits a distinctive three-stage profile of “rapid ascent–stable transition–fine optimization,” which sharply contrasts with the monotonically slow growth characteristic of the traditional SPGD algorithm. This intelligent mode-switching mechanism not only significantly accelerates the convergence speed, but the incorporated convergence stagnation detection also ensures that the algorithm reliably converges near the global optimum, effectively decreasing the local extrema probability and performance fluctuations commonly caused by parameter sensitivity in traditional algorithms. Furthermore, we measured the time overhead of the MSSPGD iteration process, which includes sequential operations such as camera exposure (2 ms), data transmission, algorithm computation, DM actuation and the DAC-induced delay (2 ms). Under the aforementioned experimental conditions, the SLAO system achieved a stable closed-loop cycle time of 5 ms, corresponding to a wavefront correction rate of 200 Hz. It should be noted that this update rate is limited by the overall system latency and the response characteristics of individual components, such as the imaging sensor and deformable mirror. Consequently, the achievable correction bandwidth in the current setup cannot reach the typical Greenwood frequency associated with atmospheric turbulence. Nevertheless, within these hardware constraints, the proposed MSSPGD algorithm demonstrates stable convergence and effective turbulence mitigation. With higher-speed hardware, the same algorithmic framework can be scaled to support significantly higher correction rates suitable for dynamic FSOC applications. The experimental results fully validate the effectiveness and robustness of the MSSPGD algorithm in improving system coupling efficiency, providing an efficient optimization solution for high-precision adaptive optics systems.

It is particularly noteworthy that the convergence speeds of both algorithms in the experimental environment are significantly slower compared to those observed in simulation. This discrepancy primarily stems from differences between the actual characteristics of the self-developed 37-element deformable mirror used in the experiment and the ideal linear-response model employed in the simulation. Specifically, the hysteresis nonlinearity of the deformable mirror results in a complex nonlinear mapping between the actuator voltages and the mirror surface deformation. Consequently, the voltage commands output by the algorithm cannot be precisely translated into the intended wavefront corrections, leading to deviations between the actual and expected correction effects at each iteration. This mismatch manifests as reductions in both convergence speed and coupling efficiency. In addition to hysteresis nonlinearity, factors such as readout noise in the optical detection system during experiments introduce additional interference into the convergence process; these factors are not fully accounted for in simulations. The extra random perturbations caused by noise degrade the performance metric observations and reduce the reliability of gradient estimation. Therefore, modeling the hysteresis nonlinearity of the deformable mirror and developing targeted optimization strategies to enhance noise robustness represent the key directions for further improvement of the proposed algorithm.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses several limitations of conventional sensor-less wavefront correction methods used in FSOC systems for correcting atmospheric turbulence-induced aberrations, including slow convergence, sensitivity to parameter selection, and susceptibility to local optima. To overcome these challenges, we propose a novel SPGD algorithm enhanced with a modal stage strategy. The algorithm implements a hierarchical wavefront correction mechanism by constructing a dynamic Zernike modal subspace, which switches between low-order and high-order modes based on convergence detection. In the coarse search phase, low-order Zernike modes that dominate turbulence-induced aberrations are employed to achieve rapid preliminary correction. Upon detecting stagnation in the convergence curve, the method switches to a full-mode refinement stage to precisely optimize higher-order aberrations, thereby ensuring comprehensive correction accuracy.

Moreover, the algorithm incorporates an adaptive learning rate adjustment scheme that dynamically modulates the learning rate based on the performance metric measured during convergence under varying turbulence intensities, effectively balancing convergence speed and correction precision. Both numerical simulations and experimental validations were conducted to assess the MSSPGD algorithm’s performance under different turbulence conditions.

Both simulation and experimental results demonstrate that, compared with the conventional SPGD algorithm, the MSSPGD algorithm significantly reduces computational complexity and improves optimization efficiency by employing dimensionality reduction techniques. It also exhibits superior stability and robustness across varying turbulence strengths and parameter settings. The proposed algorithm represents a promising and practical solution for real-time wavefront correction in high-order high-speed FSOC systems, offering potential for wide application in next-generation optical communication technologies.