Reconfigurable Cascaded Chirped-Grating Delay Lines for Silicon Photonic Convolutional Computing

Abstract

1. Introduction

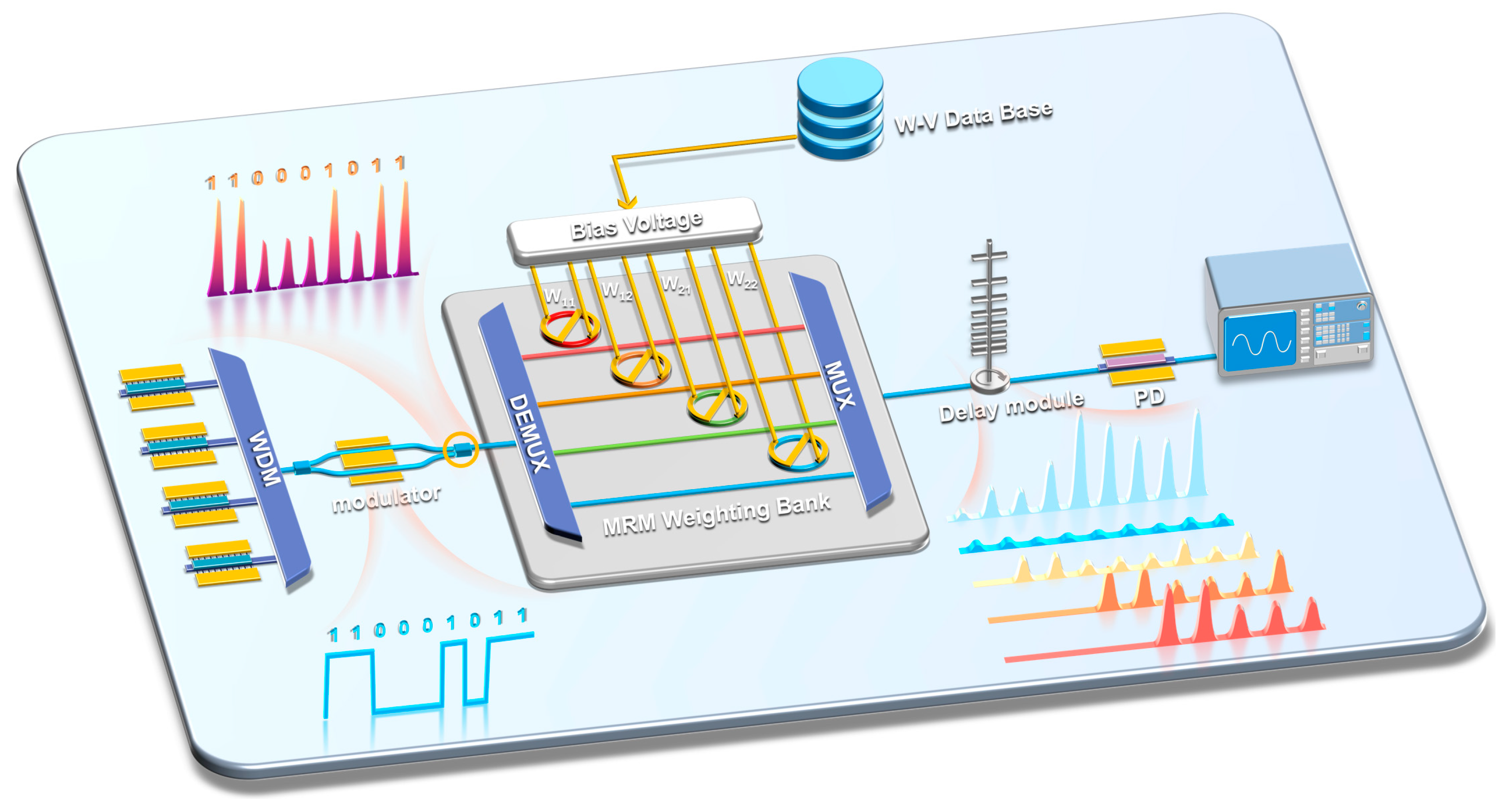

2. Theoretical Analysis and Mathematical Model

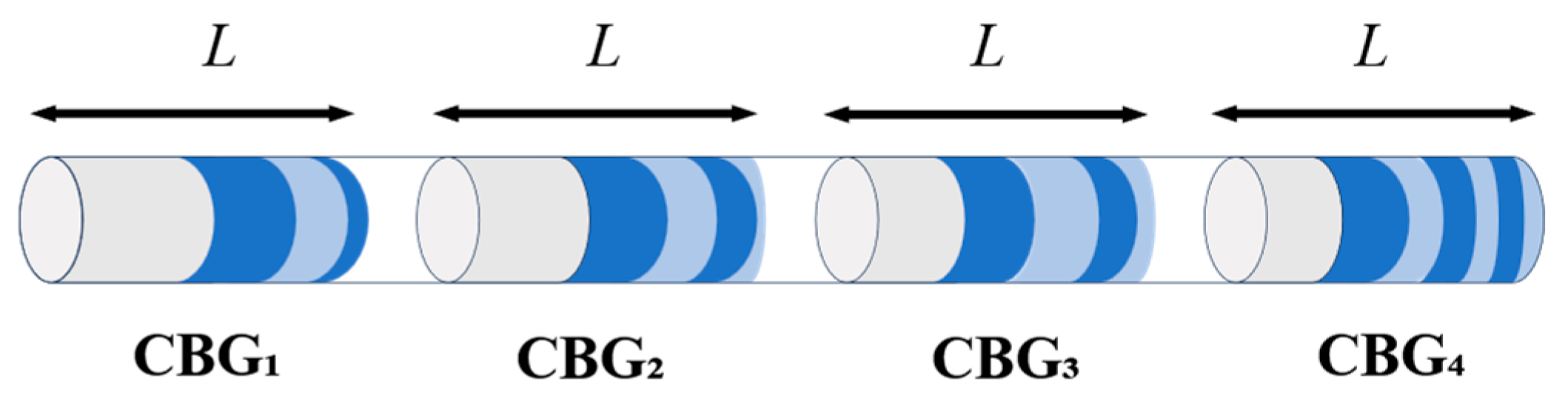

3. Design and Implementation of On-Chip CCFBG TTD Line

3.1. Component Design

- Channel 1 needs 4 bit (40 ps) → λ ≈ 1548.4 nm, time-delay: 25 ps + Δτheating (~15 ps)

- Channel 2 needs 3 bit (30 ps) → λ ≈ 1548.0 nm, time-delay: 25 ps + Δτheating (~5 ps)

- Channel 3 needs 1 bit (10 ps) → λ ≈ 1547.6 nm, time-delay: 0 ps +Δτheating (~10 ps)

- Channel 4 keeps undelayed → λ = 1547.2 nm

- Channel 1 needs 5 bit (50 ps) → λ ≈ 1548.8 nm, time-delay: 50 ps

- Channel 2 needs 4 bit (40 ps) → λ ≈ 1548.4 nm, time-delay: 50 ps + Δτheating (~−10 ps)

- Channel 3 needs 1 bit (10 ps) → λ ≈ 1547.6 nm, time-delay: 0 ps + Δτheating (~10 ps)

- Channel 4 keeps undelayed → λ = 1547.2 nm

3.2. On-Chip Implementation and Manufacturability

3.3. Comparison of Delay Schemes and Positioning of This Work

4. Numerical Simulation and Results Analysis

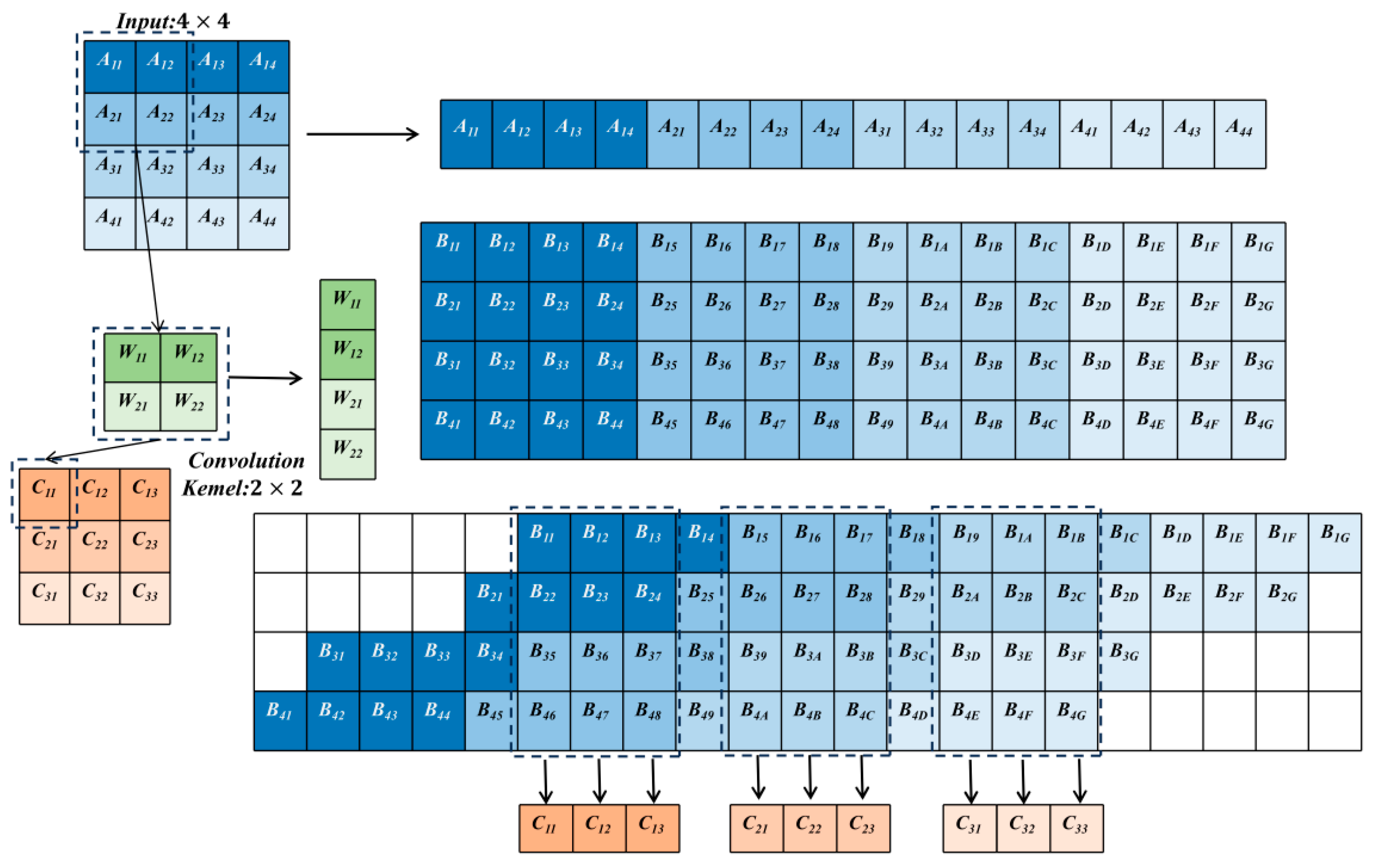

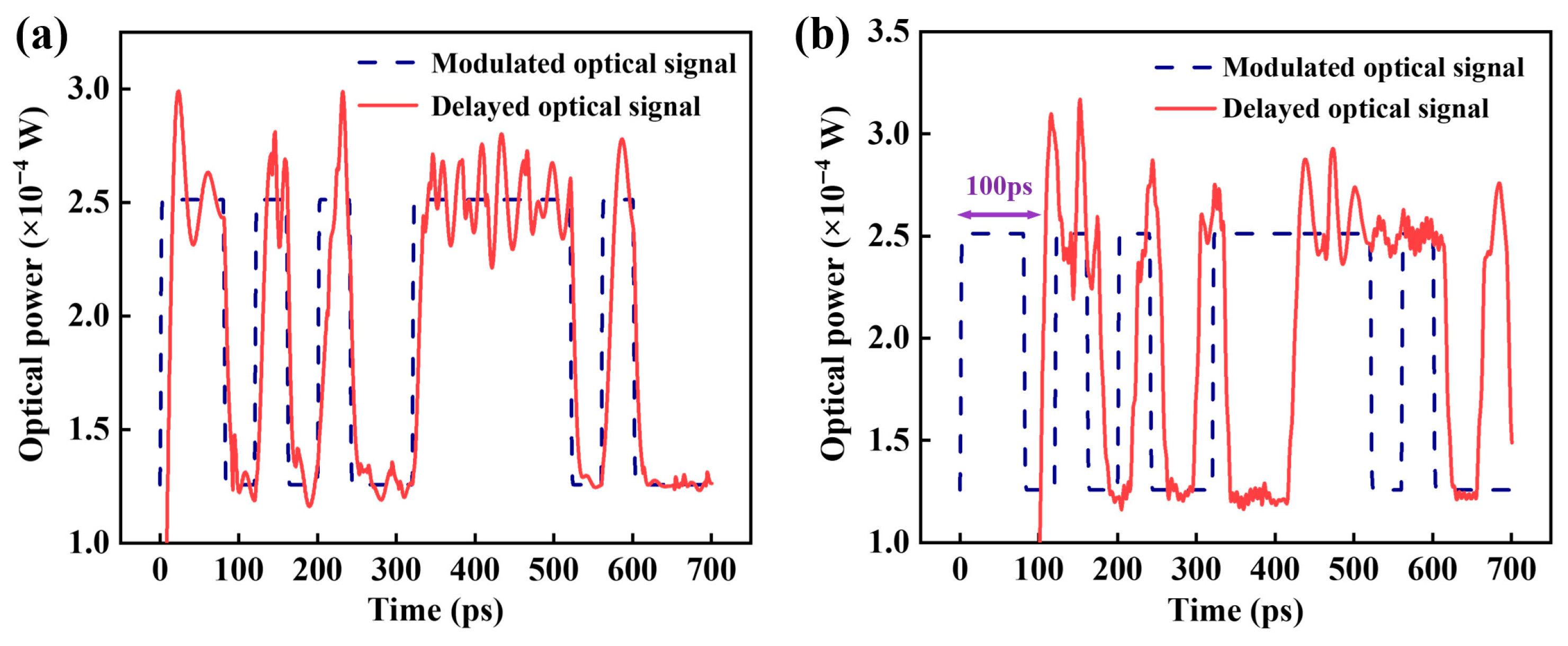

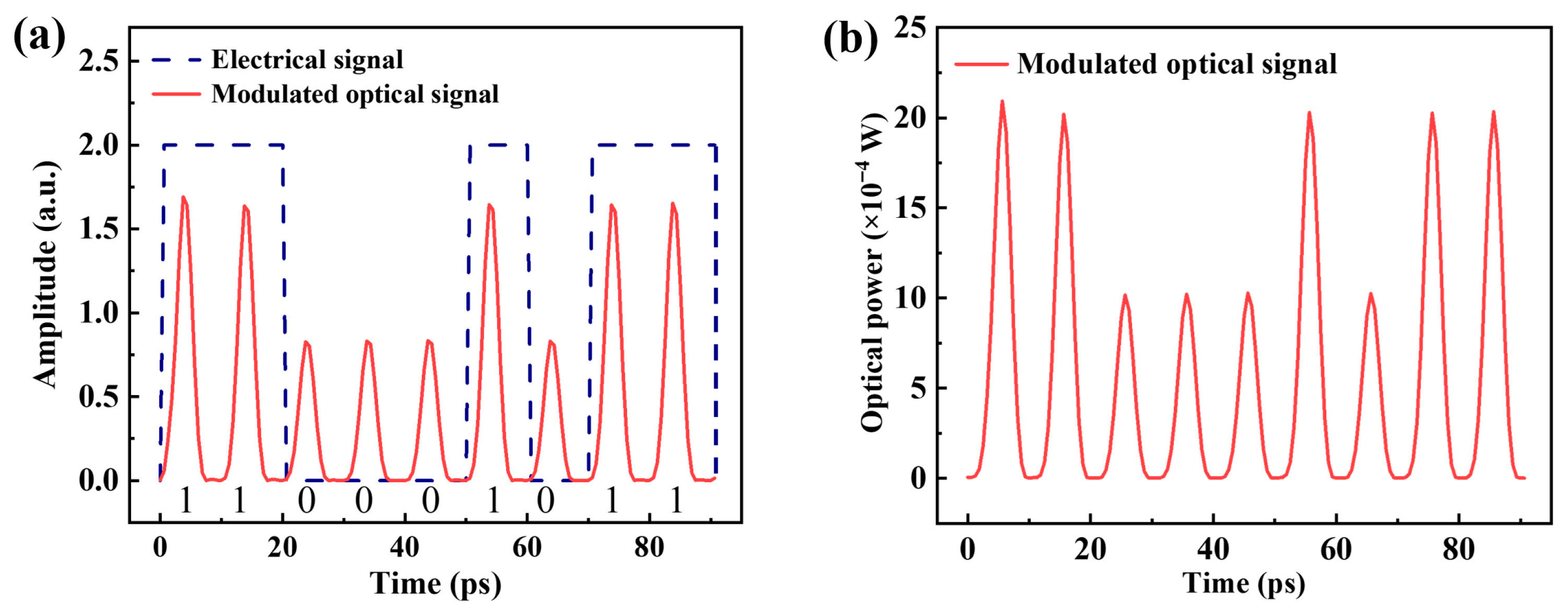

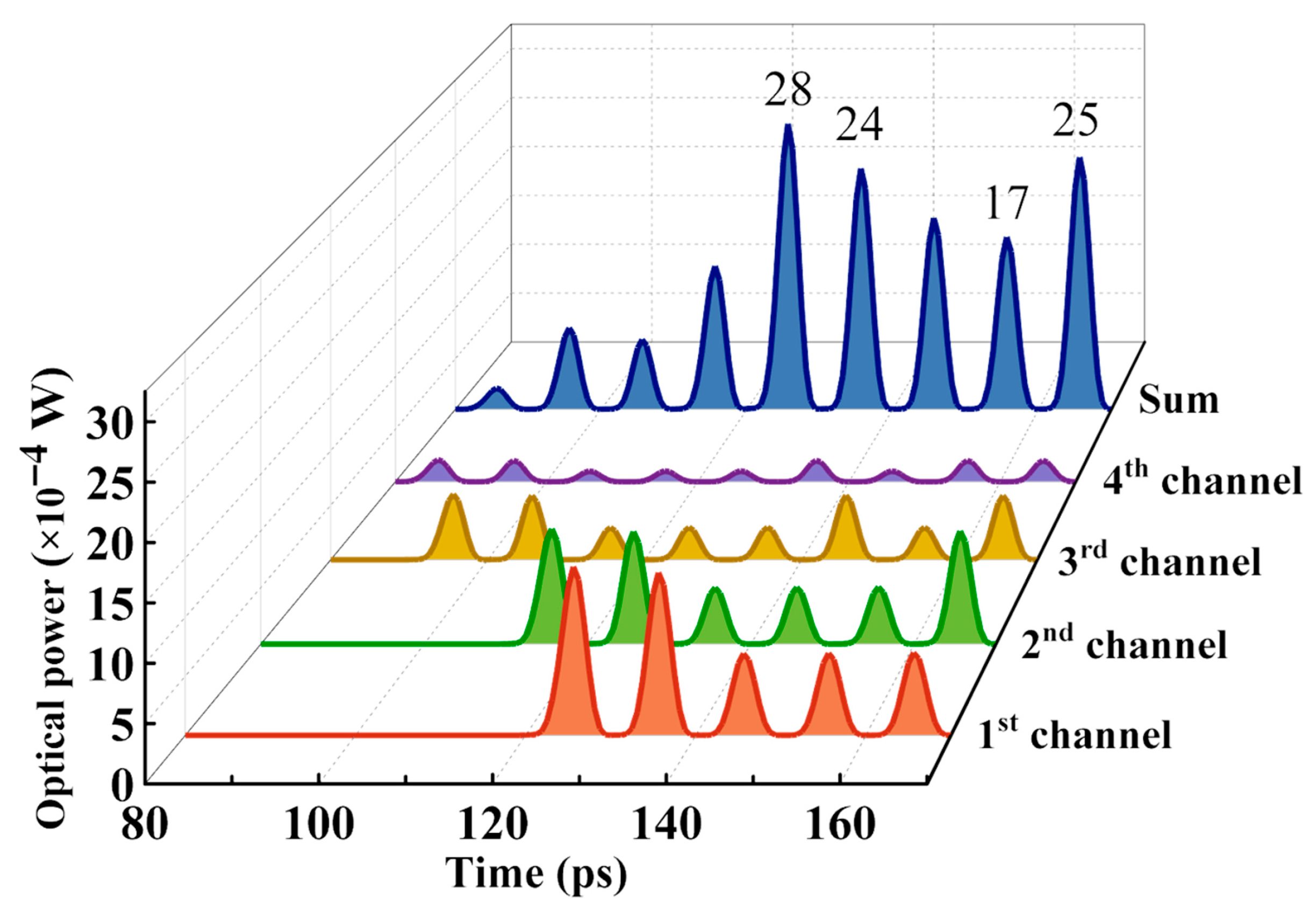

4.1. Computing Results of 3rd-Order Matrix Convolution

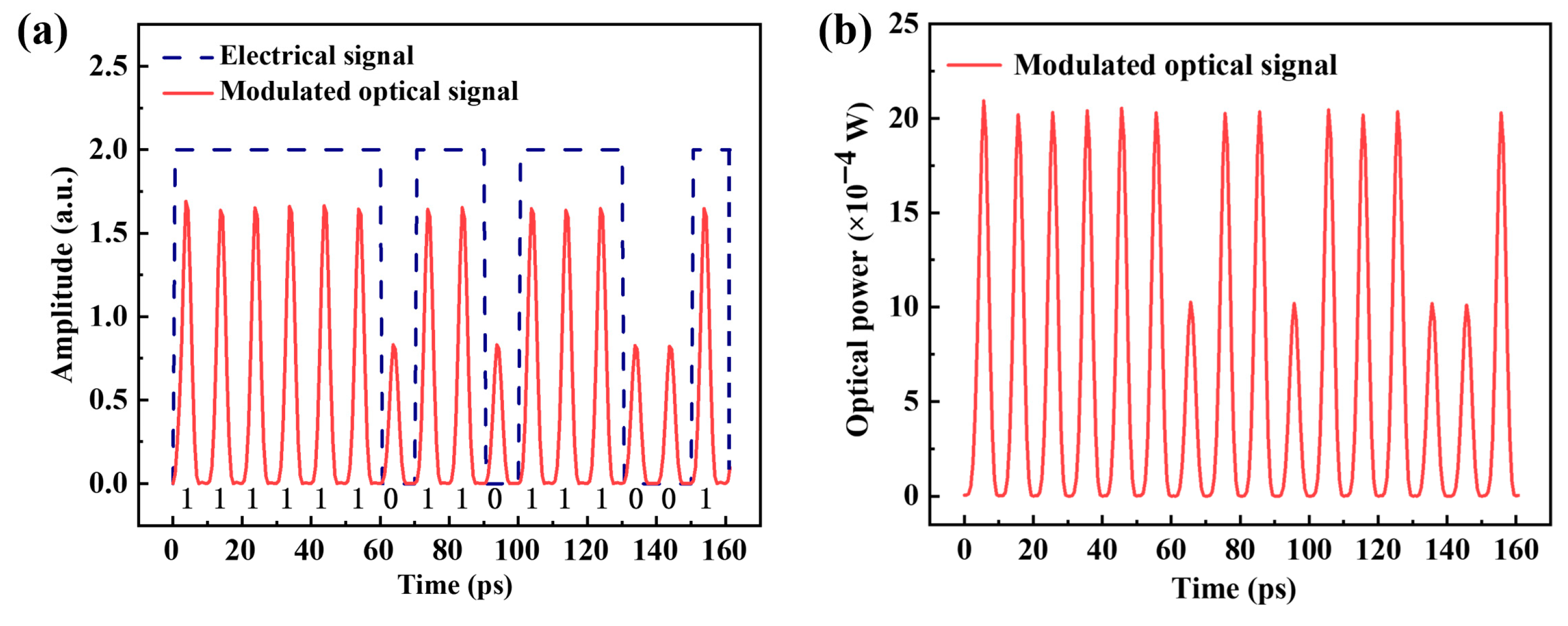

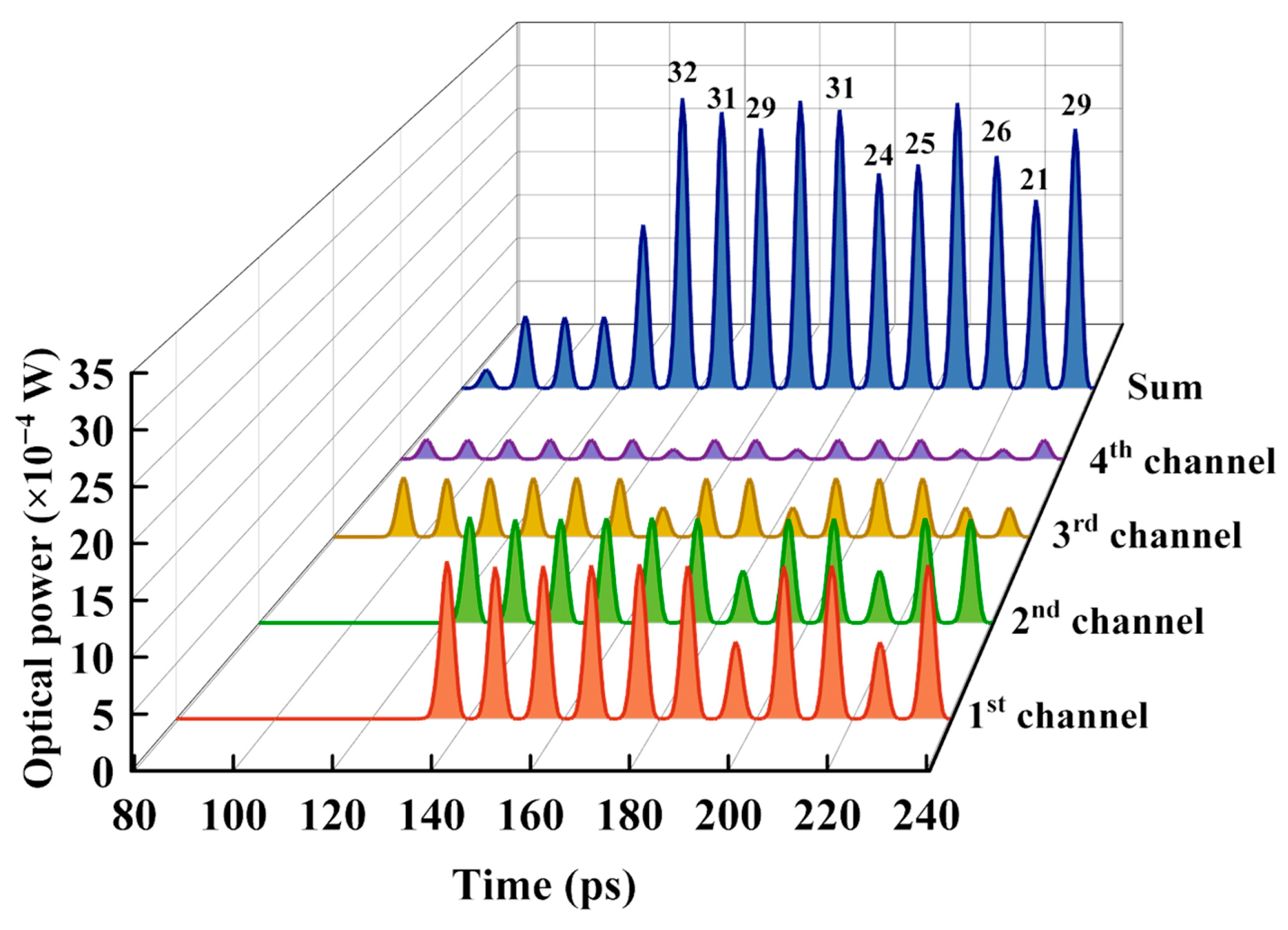

4.2. Computing Results of the 4th-Order Matrix Convolution

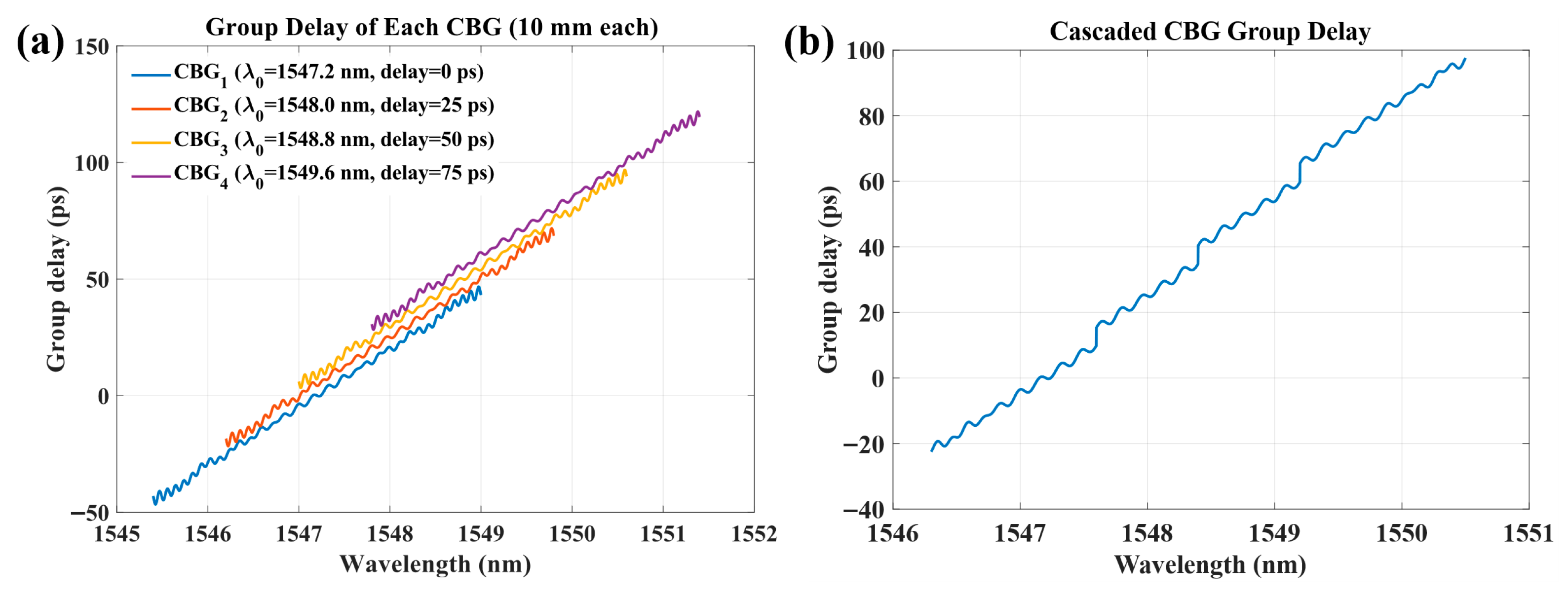

4.3. Group-Delay and Reflection Characteristics of the Cascaded CBG Delay Line

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zang, Y.; Dan, Y.; Xu, K. Advances and challenges of optical neural networks. Chin. J. Lasers 2020, 47, 0500004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Sun, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, H. Review of on-chip integrated optical neural networks. Chin. J. Lasers 2024, 51, 0119002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; Du, J.; He, Z. Programmable matrix operation with reconfigurable time-wavelength plane manipulation and dispersed time delay. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 20456–20467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnik, B.; Hung, Y.-C.; Tazawa, H.; Seo, B.-J.; Luo, J.; Jen, A.K.-Y. Electrooptic polymer ring resonator modulation up to 165 GHz. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2007, 13, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; He, Z. Photonic Convolution Neural Network Based on Interleaved Time-Wavelength Modulation. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 4592–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huang, C.-B.; Leaird, D.E.; Weiner, A.M. Optical arbitrary waveform processing of more than 100 spectral comb lines. Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Xie, Q. Programmable schemes on temporal processing of optical pulses for high-speed photonic subsystems. In Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC); Optical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. M1B.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touch, J.; Badawy, A.; Sorger, V. Optical computing. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, D.; Soriano, M.C.; Fischer, I. High-speed optical vector and matrix operations using a semiconductor laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2013, 25, 1680–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; He, Z. Optical matrix manipulation based on frequency comb modulation and dispersed time delay. In Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC); Optical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. M1B.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sepehrian, H.; Xu, Y.; Rusch, L.A.; Shi, W. Frequency comb generation using a CMOS compatible SiP M-MZM for flexible networks. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2018, 30, 1495–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Huo, Y.; Chen, M.; Yang, S.; Chen, H. Spatial-mode-coupling-based dispersion engineering for integrated optical waveguide. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 2807–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Niu, H.; Shi, W.; Lin, D.; Li, S.; Pan, S.; Yun, B. Integrated Optical Tunable Delay Line and Microwave Photonic Beamforming Chip: A Review. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2400663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, J.; Foster, M.A.; Sherwood-Droz, N.; Poitras, C.B.; Lira, H.L.R.; Zhang, B.; Gaeta, A.L.; Khurgin, J.B.; Morton, P.; Lipson, M. Wide-bandwidth continuously tunable optical delay line using silicon microring resonators. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 26525–26534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Davenport, M.L.; Khurgin, J.B.; Morton, P.A.; Bowers, J.E. Low-Loss Continuously Tunable Optical True Time Delay Based on Si3N4 Ring Resonators. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2018, 24, 5900109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. Seven-bit reconfigurable optical true time delay line based on silicon integration. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 22707–22715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, D.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X. Large group delay and low loss optical delay line based on chirped waveguide Bragg gratings. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 4630–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.; Li, C.; Dai, T.; Zhong, C.; Lin, H.; Hu, X.; Gong, Q. Matrix eigenvalue solver based on reconfigurable photonic neural network. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 4089–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.Q.; Hu, Z.F.; Chen, K.X. Scalable and reconfigurable true time delay line based on an ultra-low-loss silica waveguide. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 4434–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.S.; Lim, M.G.; Kim, D.U.; Her, M.J.; Park, Y.J.; Choi, D.J.; Jeong, Y.; Park, J.; Han, S.; Chun, Y.H.; et al. Programmable MZI based on a silicon photonic MEMS-tunable delay line. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 5611–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Yang, J. Wideband true-time-delay beam former that employs a tunable chirped fiber grating prism. Appl. Opt. 2003, 42, 2273–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ding, Z.; Yang, F.; Cai, H. Configurable photonic true-time delay line based on cascaded linearly chirped fiber Bragg grating. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics (MWP), Toulouse, France, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.R. Integrated discretely tunable optical delay line based on step-chirped subwavelength grating waveguide Bragg gratings. J. Light. Technol. 2020, 38, 5551–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccomandi, P.; Varalda, A.; Gassino, R.; Tosi, D.; Massaroni, C.; Caponero, M.A.; Pop, R.; Korganbayev, S.; Perrone, G.; Diana, M.; et al. Linearly chirped fiber Bragg grating response to thermal gradient: From bench tests to the real-time assessment during in vivo laser ablations of biological tissue. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 097002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.B.; Parker, M.E.; Dexter, J.L. Demonstration of a Continuously Variable True-Time Delay Beamformer Using a Multichannel Chirped Fiber Grating. IEEE Microw. Theory Tech. 2006, 54, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Li, X.; Jacques, M.; Berikaa, E.; Koh, P.C.; Plant, D.V. Net 300 Gbps/λ transmission over 2 km of SMF with a silicon photonic mach-zehnder modulator. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2021, 33, 1391–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Rao, S.; Xu, S.; Huang, Y.; Cai, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; et al. Spectral convolutional neural network chip for in-sensor edge computing of incoherent natural light. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Wu, K.; Chen, J. Tunable spiral Bragg gratings in 60-nm-thick silicon-on-insulator strip waveguides. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 12831–12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Flueckiger, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yun, H.; Lu, Z.; Caverley, M.; Wang, Y.; Jaeger, N.A.F.; Chrostowski, L. Spiral Bragg grating waveguides for TM mode silicon photonics. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 25295–25307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Dai, D. Ultralow-loss compact silicon photonic waveguide spirals and delay lines. Photonics Res. 2022, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grating | Central Wavelength λ (nm) | Period of the CBG Λ (nm) | Design Group Delay (ps) | Fine-Tuning by Heating (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBG1 | 1547.2 | 525.6 | 0 | ±12 |

| CBG2 | 1548.0 | 525.9 | 25 | ±12 |

| CBG3 | 1548.8 | 526.3 | 50 | ±12 |

| CBG4 | 1549.6 | 526.6 | 75 | ±12 |

| Scheme | Delay Range/Step | Reconfigurability | Insertion Loss | Footprint | Power/Calibration Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZI arrays (phase) | 0–100 ps; step 1–5 ps | High (continuous weights, discrete paths) | 10–20 dB (scale-dependent) | >a few mm2 (O(N2) ports) | 0.5–2 W; complex (multi-parameter non-convex tuning) |

| Microcomb + dispersive network (TTD/WDM) | 0.1→1000 ps | Medium (selectable channels/weights, but discrete) | 15–30 dB (WDM/EOM/EDFA accumulation) | often cm-scale dispersion/peripherals | \ |

| Fixed-fiber-delay PCNN (discrete branches) | Discrete by fiber length (10 ps-ns) | Medium (switch/selection only) | <5 dB per branch (excluding couplers) | coiled fiber/rack-scale | \ |

| Our design cascaded CBG (true time delay) | 0–100 ps continuous (in-band); step < 1 ps | High (continuous true delay; reusable across convolution orders) | ≈1–3 dB per grating; cascade ≈4–8 dB (process-dependent) | <10 mm × few hundred μm | <100 mW (steady-state thermal) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, G.; Chen, G.; Lu, L.; She, F.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, B.; Chun, S.; Li, Y. Reconfigurable Cascaded Chirped-Grating Delay Lines for Silicon Photonic Convolutional Computing. Photonics 2025, 12, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12100974

Zhong G, Chen G, Lu L, She F, Xu Y, Yang J, Wu B, Chun S, Li Y. Reconfigurable Cascaded Chirped-Grating Delay Lines for Silicon Photonic Convolutional Computing. Photonics. 2025; 12(10):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12100974

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Guangping, Guang Chen, Lidan Lu, Fengyu She, Yingjie Xu, Jieyu Yang, Bangze Wu, Senyan Chun, and Yulin Li. 2025. "Reconfigurable Cascaded Chirped-Grating Delay Lines for Silicon Photonic Convolutional Computing" Photonics 12, no. 10: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12100974

APA StyleZhong, G., Chen, G., Lu, L., She, F., Xu, Y., Yang, J., Wu, B., Chun, S., & Li, Y. (2025). Reconfigurable Cascaded Chirped-Grating Delay Lines for Silicon Photonic Convolutional Computing. Photonics, 12(10), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics12100974