Uncarbonized Bovine Bone/MOF Composite as a Hybrid Green Material for CO and CO2 Selective Adsorption

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bovine Bone Matrix Preparation

2.2. Preparation of the Composite

2.3. Characterization

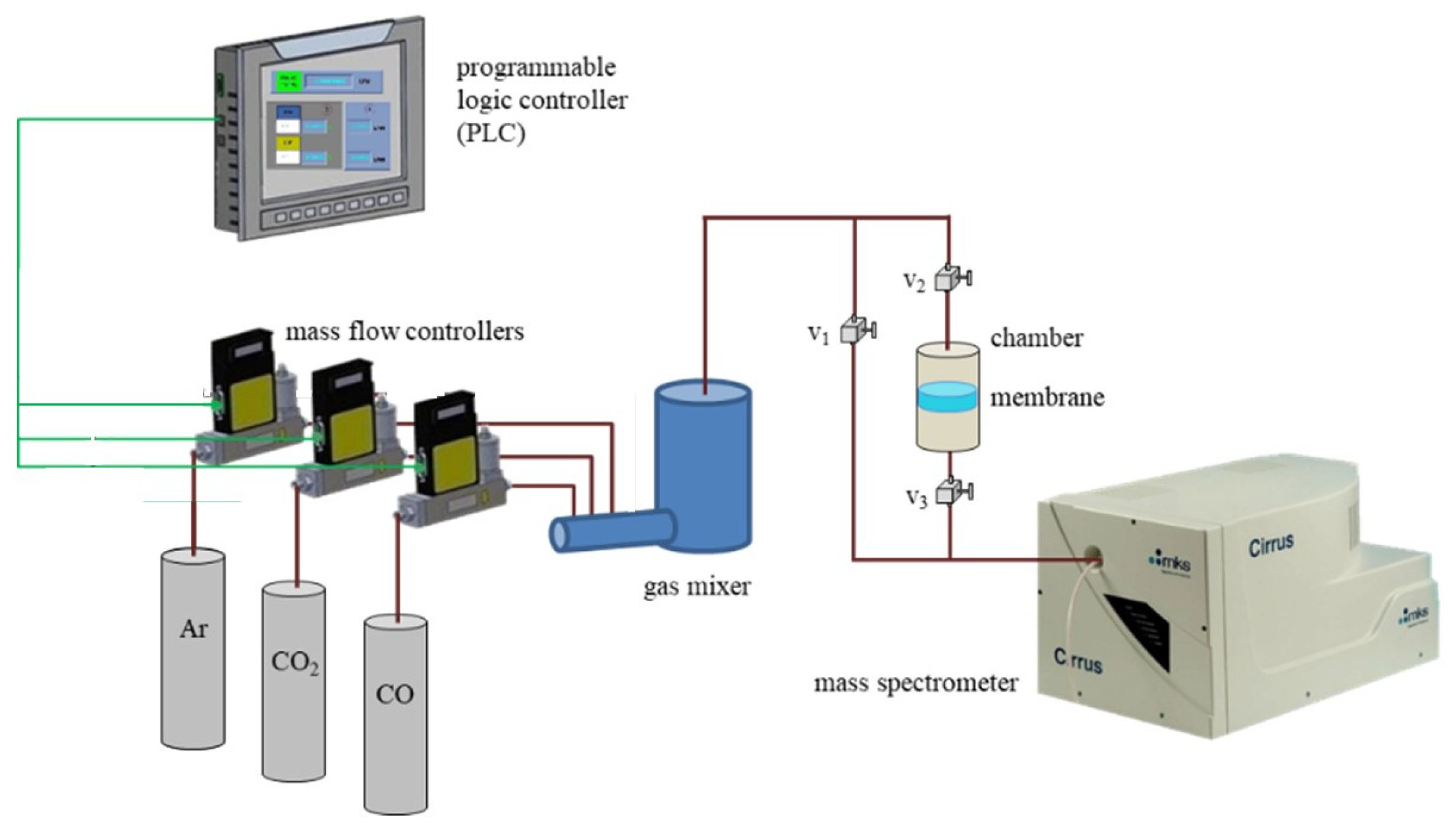

2.4. Gas Adsorption by the Composite

3. Results and Discussion

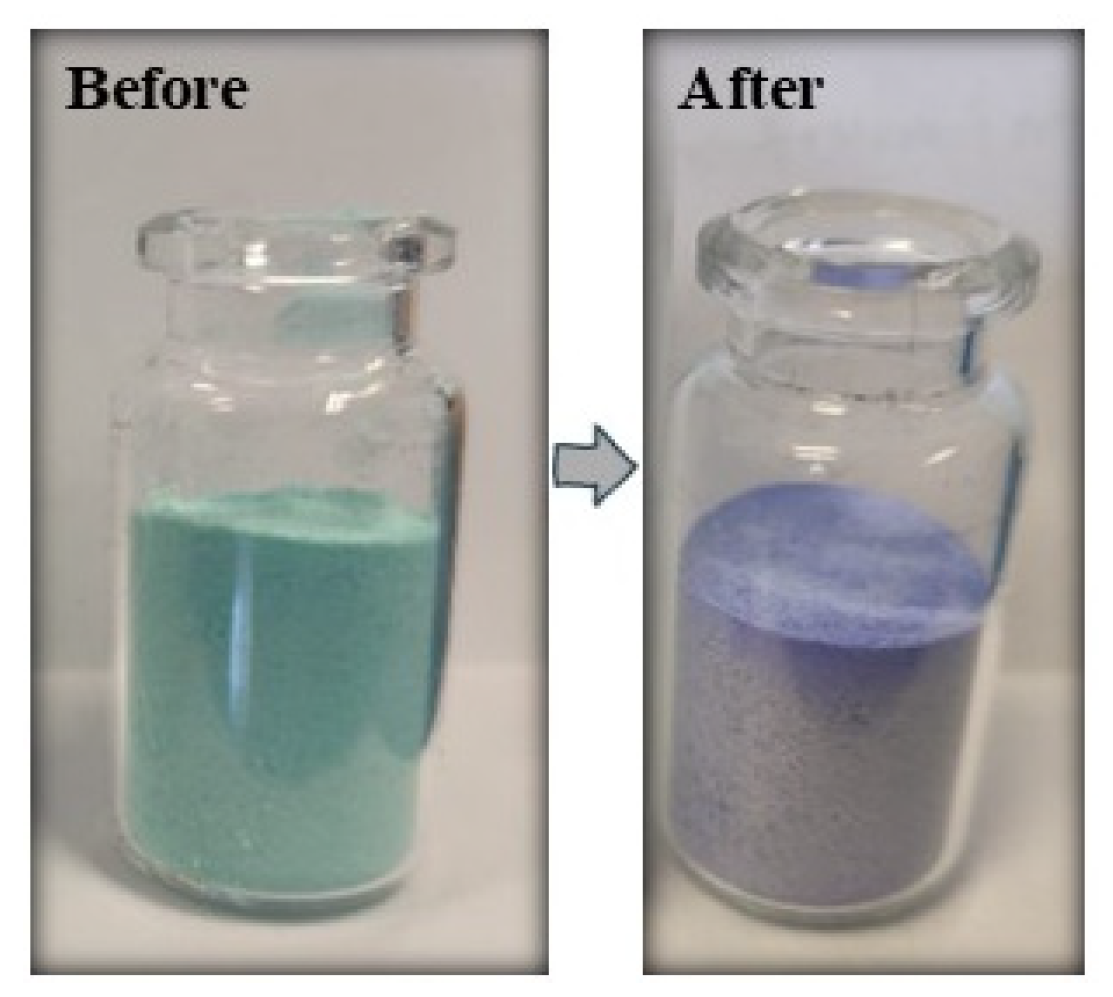

3.1. Synthesis of Composites

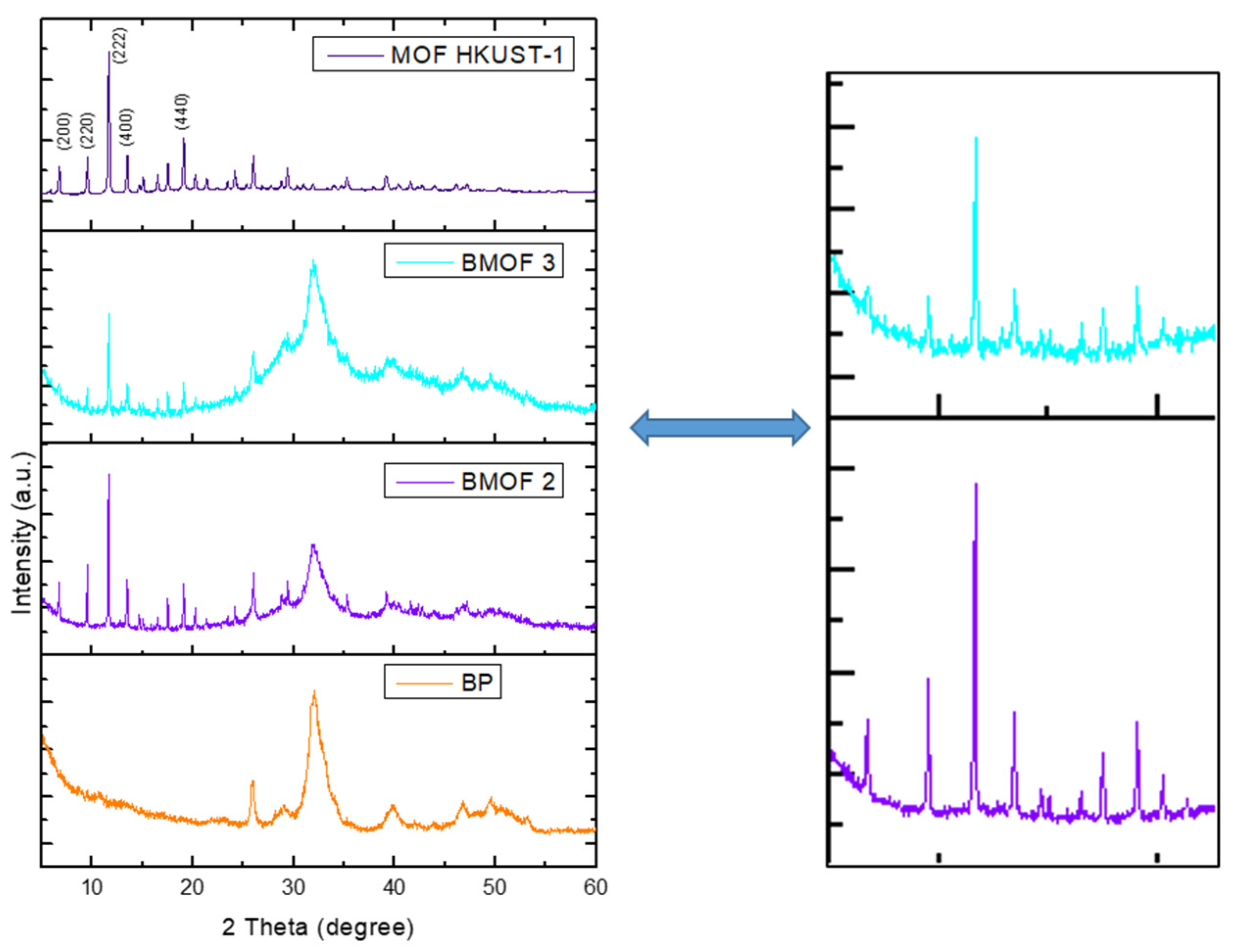

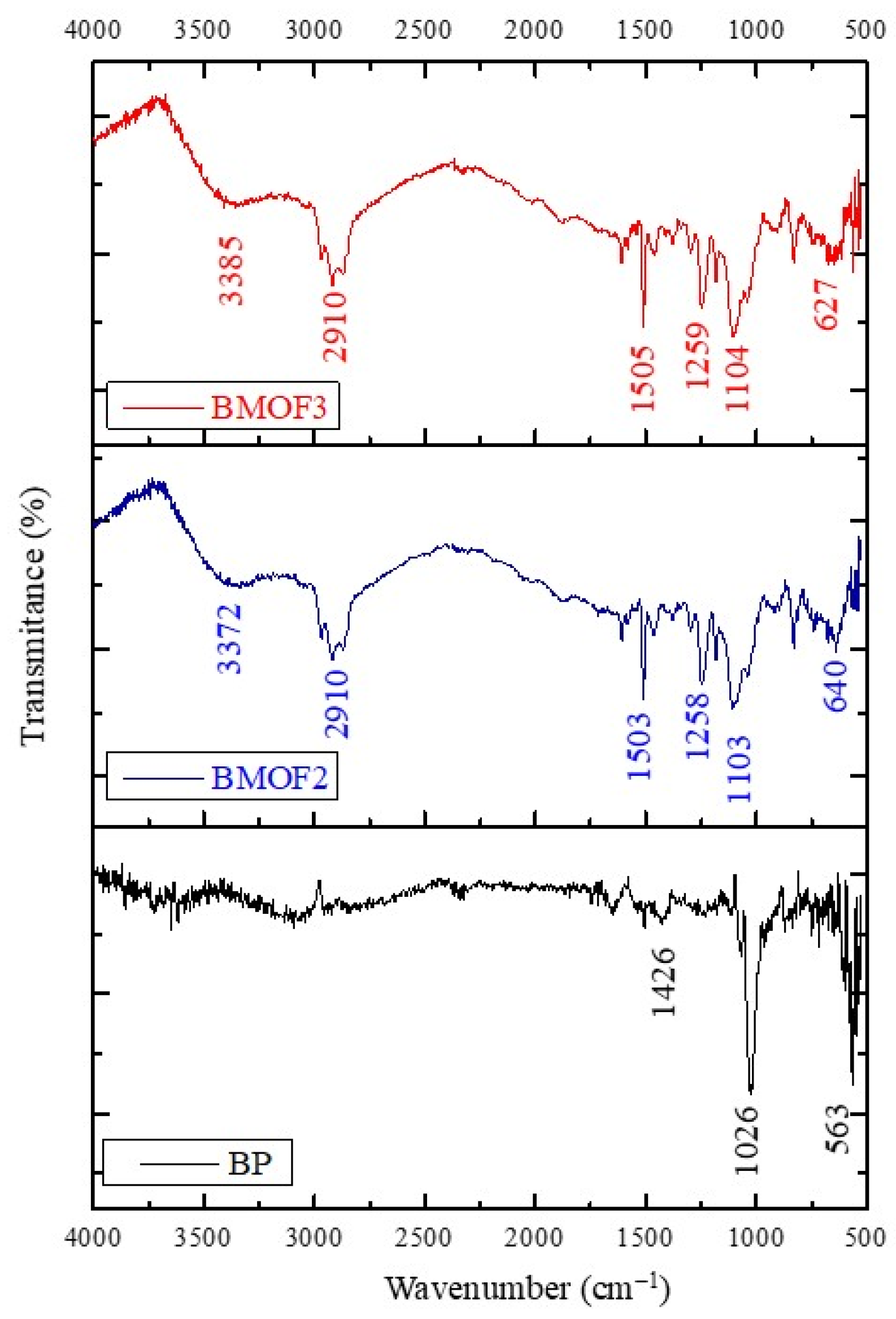

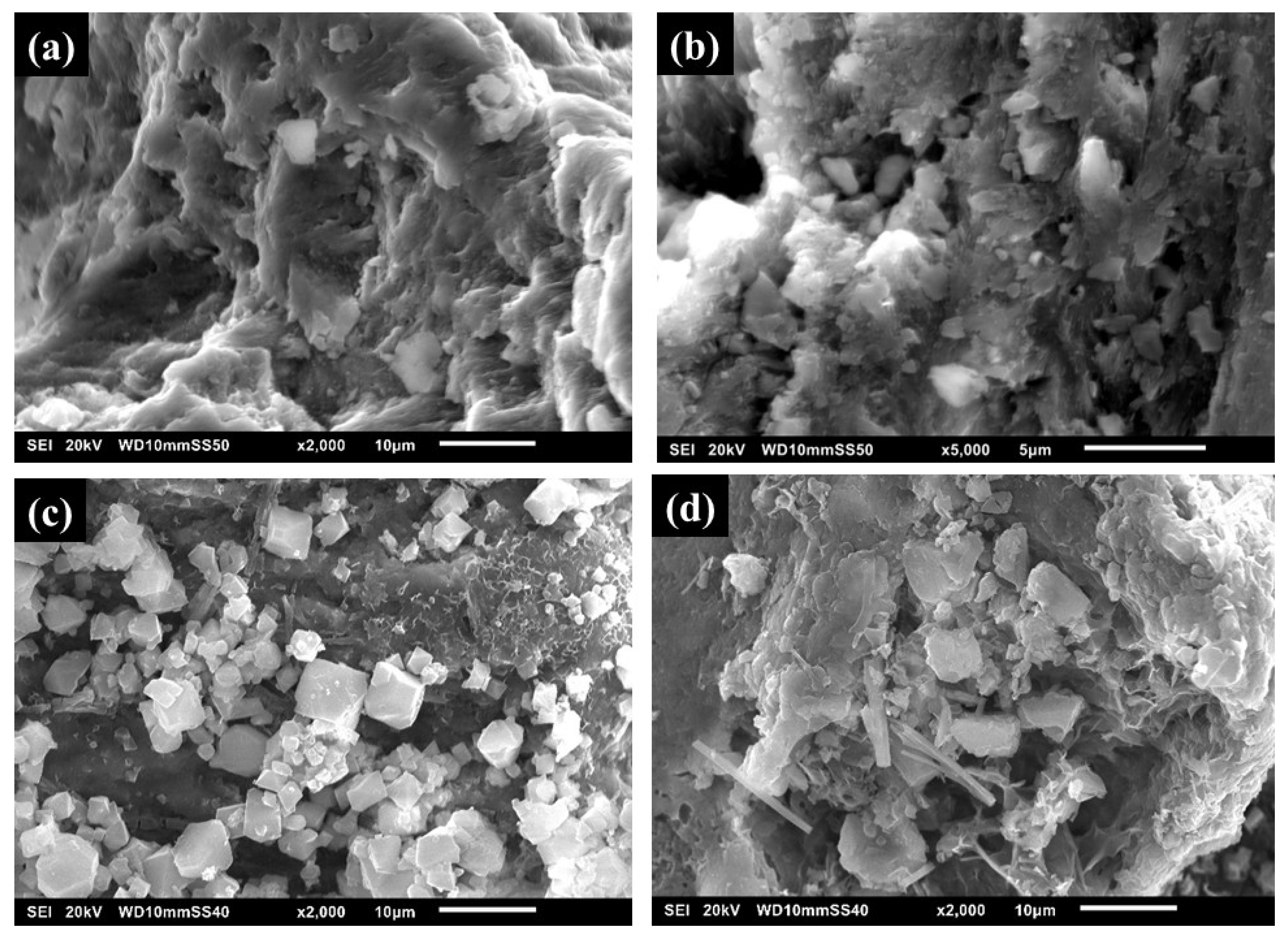

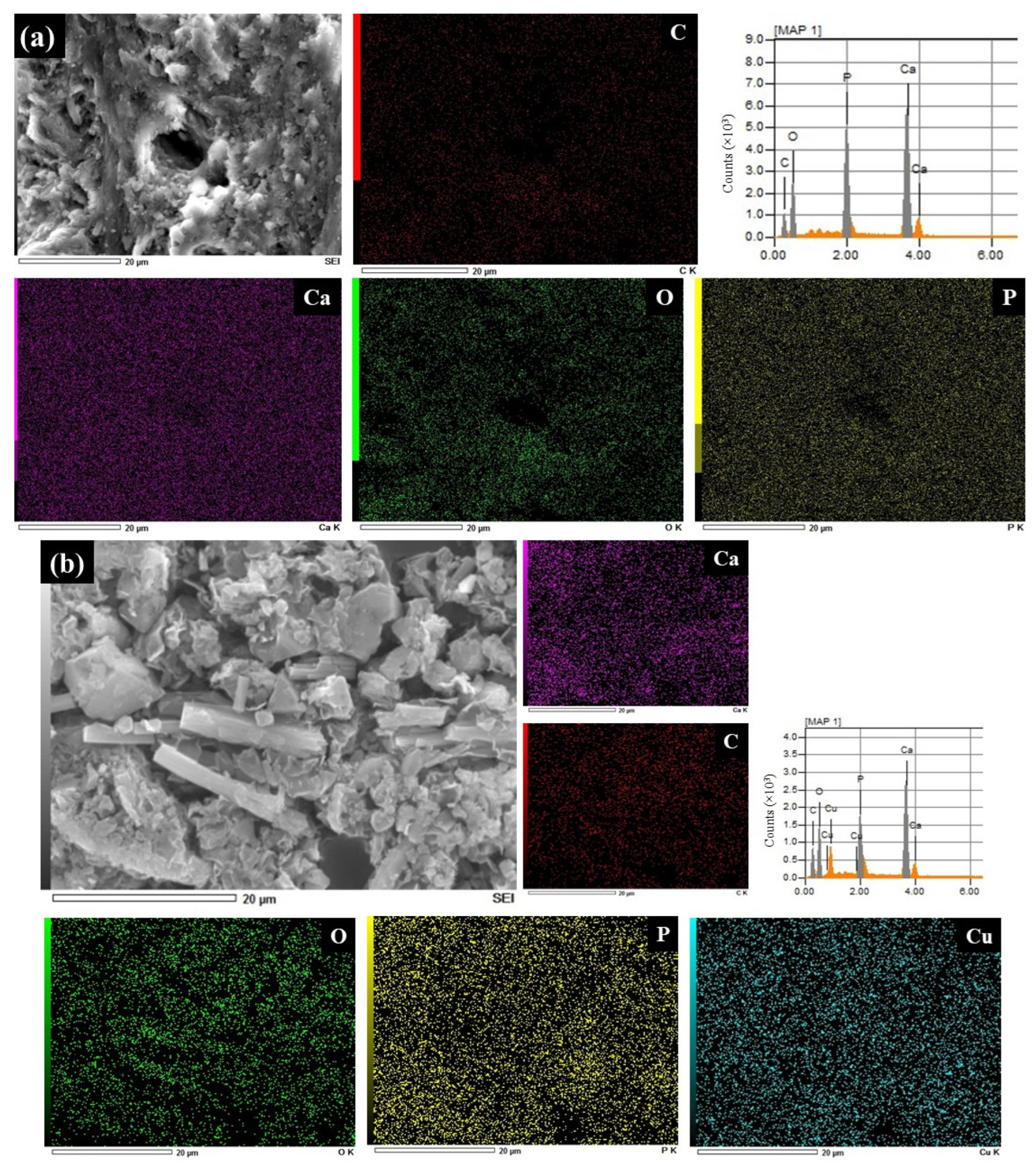

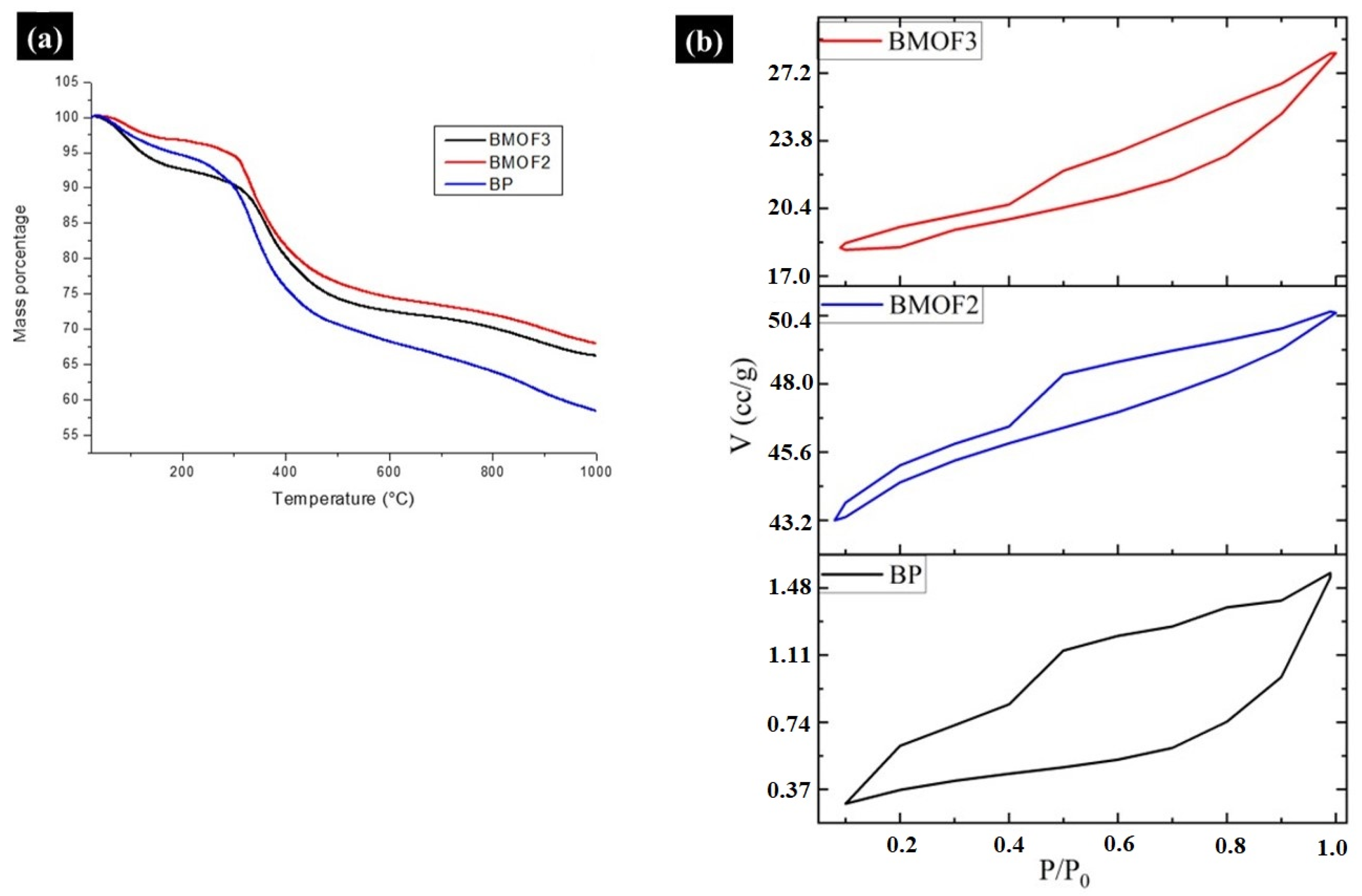

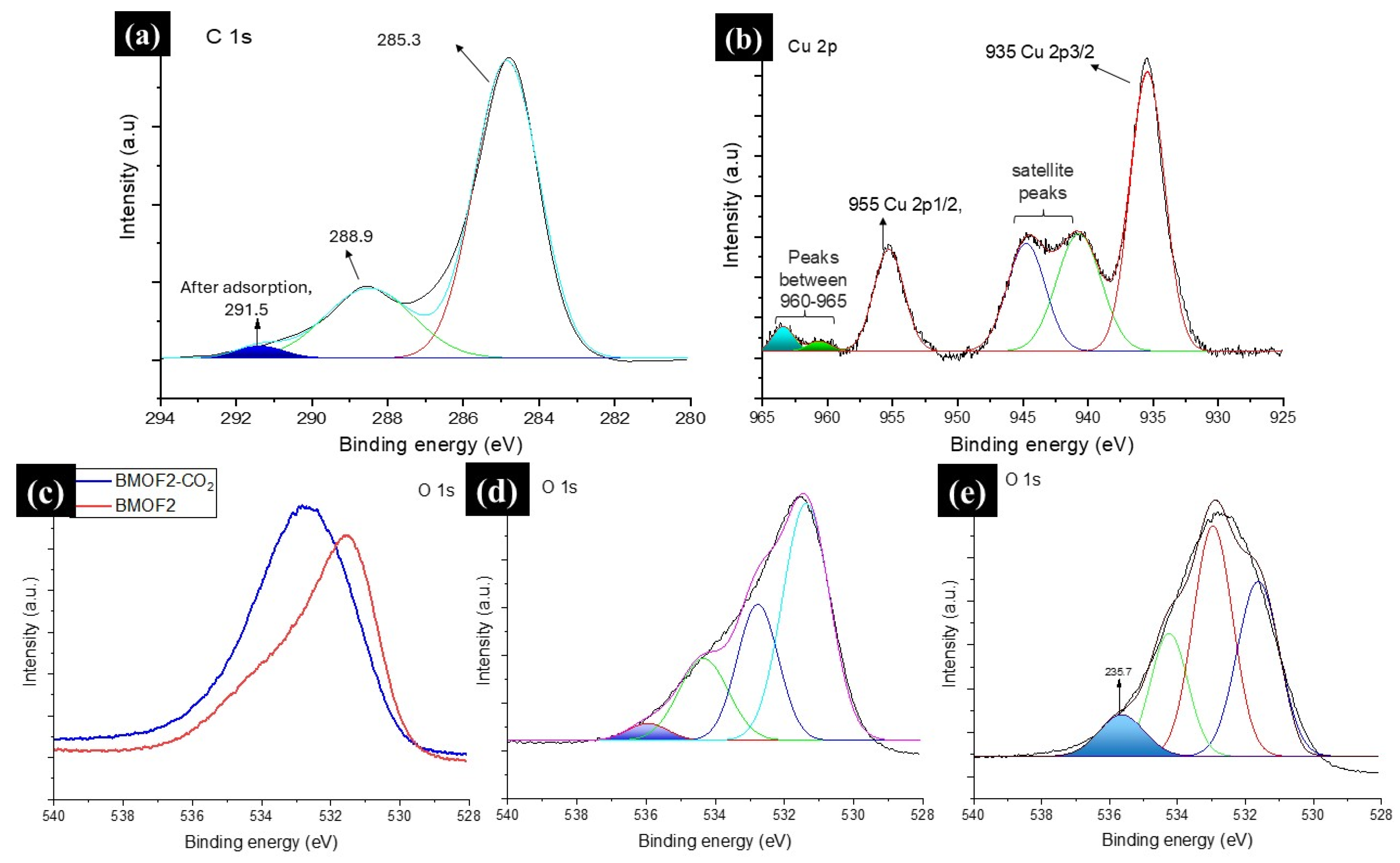

3.2. Characterization of BP, BMOF2, and BMOF3 Materials

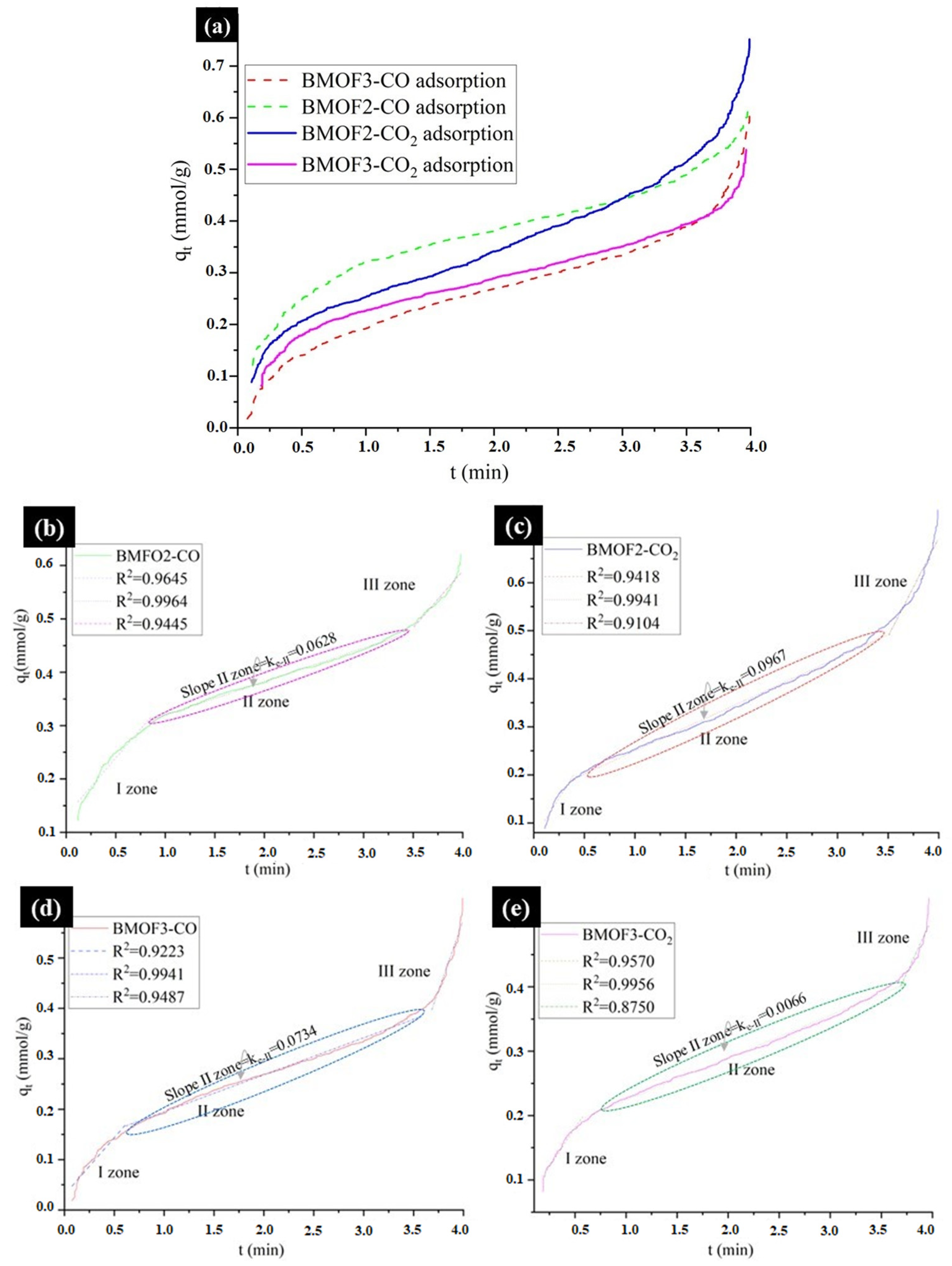

3.3. CO and CO2 Adsorption onto Composites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pathak, M.; Slade, R.; Shukla, P.R.; Skea, J.; Pichs-Madruga, R.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Technical Summary. In Climate Change. 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J.R., Slade, A., Al Khourdajie, R., van Diemen, D., McCollum, M., Pathak, S., Some, P., Vyas, R., Fradera, M., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://climatetrace.org/news/climate-trace-begins-monthly-data-releases-with-new (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Khan, T.; Jimenez, C.; Pineda, L.; Yang, Z.; Miller, J.; Sen, A. CO2 Emission Standards to Achieve Mexico’s 2030 Electrification Target for Light-Duty Vehicles; ICCT Policy Brief: Berlin, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Turner, A.J.; Yin, Y.; Prather, M.J.; Frankenberg, C. Effects of chemical feedbacks on decadal methane emissions estimates. Geophis. Res. Let. 2020, 47, e2019GL085706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Fu, H.; Tong, Y.; Umar, A.; Hung, Y.M.; Wang, X. Advances in CO2 Capture and Separation Materials: Emerging Trends, Challenges, and Prospects for Sustainable Applications. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttil, N.; Jagadeesan, S.; Chanda, A.; Duke, M.; Singh, S.K. Production, types, and applications of activated carbon derived from waste tyres: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Xiao, R.; Yang, C.; Xin, M.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, G. Recent advances in advanced membrane materials for natural gas purification: A review of material design and separation mechanisms. Membranes 2025, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekou, T.K.; Koutsonikolas, D.E.; Karagiannakis, G.; Kikkinides, E.S. Tailor-made modification of commercial ceramic membranes for environmental and energy-oriented gas separation applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, K.; Yu, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, H.; Xia, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; et al. Review of electrochemical carbon dioxide capture towards practical application. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.; Valdivia, R.; Pacheco, M.; Clemente, A. H2 yielding rate comparison in a warm plasma reactor and thermal cracking furnace. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 31243–31254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; An, H.; Qin, C.; Yin, J.; Wang, G.; Feng, B.; Xu, M. Performance enhancement of calcium oxide sorbents for cyclic CO2 capture—A review. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 2751–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahby, A.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. CO2 adsorption on carbon molecular sieves. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 164, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizundia, E.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D. Organic waste valorization towards circular and sustainable biocomposites. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5429–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Meat Consumption, World, 1961 to 2050. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-meat-projections-to-2050 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Orús, A. 30 Ago 2023. Volumen De Carne Consumida a Nivel Mundial De 1990 a 2022, Por Tipo De Carne. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1330024/consumo-de-carne-a-nivel-mundial-por-tipo/#:~:text=Consumo%20de%20carne%20a%20nivel%20mundial%20por%20tipo%201990%2D2022&text=El%20consumo%20mundial%20de%20carne,333%20millones%20de%20toneladas%20m%C3%A9tricas (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- La economía Circular: Un Modelo Económico Que Lleva Al Crecimiento Y Al Empleo Sin Comprometer El Medio Ambiente. 26 Marzo 2021. Asuntos Económicos. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2021/03/1490082 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Neolaka, Y.A.; Lawa, Y.; Naat, J.; Lalang, A.C.; Widyaningrum, B.A.; Ngasu, G.F.; Niga, K.A.; Darmokoesoemo, H.; Munawar, I.; Kusuma, H.S. Adsorption of methyl red from aqueous solution using Bali cow bones (Bos javanicus domesticus) hydrochar powder. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajyani, Z.; Mousavi, Z.; Soleimanbeigi, M.; Wong, Y.J.; Beni, A.A. Antibiotic adsorption from real pharmaceutical factory wastewater using a hole-punched flat ceramic membrane based on clay and hydroxyapatite in a fixed bed module. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikara, A.G.; Maharani, A.P.; Puspitasari, A.; Nuswantoro, N.F.; Juliadmi, D.; Maras, M.A.J.; Nugroho, D.B.; Saksono, B. Bovine hydroxyapatite for bone tissue engineering: Preparation, characterization, challenges, and future perspectives. Eur. Polym, J. 2024, 214, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Euw, S.; Wang, Y.; Laurent, G.; Drouet, C.; Babonneau, F.; Nassif, N.; Azaïs, T. Bone mineral: New insights into its chemical composition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, M.A.; Lee, G.; Ardianto, C.; Rantam, F.A.; Lestari, M.L.A.D.; Addimaysqi, R.; Khotib, J. Comparative study of bovine and synthetic hydroxyapatite in micro-and nanosized on osteoblasts action and bone growth. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0311652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, X.; Zeng, L.; Zeng, S.; Li, K.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Y. New insights into the co-pyrolysis synergistic effect of pig bone-derived natural hydroxyapatite and sodium-rich Spartina alterniflora on forming highly active heterostructure sites for enhanced Cu2+ removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Tan, H.; Liu, K.; Gao, W. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO/Bone Char Composite. Materials 2018, 11, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Lins, P.V.; Henrique, D.C.; Ide, A.H.; de Paiva e Silva Zanta, C.L.; Meili, L. Evaluation of caffeine adsorption by MgAl-LDH/biochar composite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31804–31811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, C.; Lin, B.; Huang, Q. Surface modified and activated waste bone char for rapid and efficient VOCs adsorption. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, O.; Ezeji, T.C. Utilization of biomass-based resources for biofuel production: A mitigating approach towards zero emission. Sustain. Chem. One World 2024, 2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Zhou, X.; Peng, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Advances in metal-organic frameworks composites: A mini review. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Lv, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Hang, X.; Pang, H. The stability of MOFs in aqueous solutions—Research progress and prospects. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Cai, X.; Jiang, H.L. Improving MOF stability: Approaches and applications. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 10209–10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourdikoudis, S.; Dutta, S.; Kamal, S.; Gómez-Graña, S.; Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Wuttke, S.; Polavarapu, L. State-of-the-art, insights, and perspectives for MOFs-nanocomposites and MOF-derived (Nano) materials. Adv. Mater. 2025, 21, e2415399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Mi, L. Porous carbon derived from metal organic framework for gas storage and separation: The size effect. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 118, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Jaldin, H.P.; Blanco Flores, A.; Pinzón-Vanegas, C.L.; Ávila-Marquez, D.M.; Reyes Domínguez, I.A.; Mahdavi, H.; Dorazco-González, A. Novel hybrid composites based on HKUST-1 and a matrix of magnetite nanoparticles with sustainable materials for efficient CO2 adsorption. Arabian J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 50, 6373–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Márquez, D.M.; Blanco Flores, A.; Toledo Jaldin, H.P.; Burke Irazoque, M.; González Torres, M.; Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Toledo, C.C.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, S.; Díaz Rodríguez, J.P.; Dorazco-González, A. MIL-53 MOF on sustainable biomaterial for antimicrobial evaluation against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria by efficient release of Penicillin G. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Yang, S.T.; Ahn, W. Bench-scale preparation of Cu3(BTC)2 by ethanol reflux: Synthesis optimization and adsorption/catalytic applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 161, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, N.; Hill, P.; Torrente-Murciano, L.; Garforth, A.; Gorgojo, P.; Siperstein, F.; Fan, X. Mapping the Cu-BTC metal–organic framework (HKUST-1) stability envelope in the presence of water vapour for CO2 adsorption from flue gases. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mu, X.; Lester, E.; Wu, T. High efficiency synthesis of HKUST-1 under mild conditions with high BET surface area and CO2 uptake capacity. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Inter. 2018, 28, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoria, N.; Basina, G.; Pokhrel, J.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Anastasiou, S.; Balasubramanian, V.V.; Karanikolos, G.N. Functionalization effects on HKUST-1 and HKUST-1/graphene oxide hybrid adsorbents for hydrogen sulfide removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 394, 122565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, P.; Paruthi, A.; Menon, D.; Behara, R.; Jaiswal, A.; Kumar, A.; Misra, S.K. Fe doped bimetallic HKUST-1 MOF with enhanced water stability for trapping Pb(II) with high adsorption capacity. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, M.J.; Caruzi, B.B.; Gil, G.A.; Samulewski, R.B.; Bail, A.; Scacchetti, F.A.P.; Maestá Bezerra, F. In-situ direct synthesis of HKUST-1 in wool fabric for the improvement of antibacterial properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, P.; Zhong, J. Facile preparation of low-cost HKUST-1 with lattice vacancies and high-efficiency adsorption for uranium. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 10320–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Restrepo, S.M.; Jeronimo-Cruz, R.; Rubio-Rosa, E.; Rodriguez-García, M.E. The effect of cyclic heat treatment on the physicochemical properties of bio hydroxyapatite from bovine bone. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltoum Kribaa, O.; Saifi, F.; Chahbaoui, N. Elaboration and chemical characterization of a composite material based on hydroxyapatite/polyethylene. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Noh, J.E.; Lee, M.J.; Chae, W.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.G. The effect of 4-hexylresorcinol on xenograft degradation in a rat calvarial defect model. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 38, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano, N.; Jikan, S.S.; Basri, H.; Adzila, S.; Zago, D.M. XRD and FTIR study of A&B type carbonated hydroxyapatite extracted from bovine bone. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Telangana, India, 5–6 December 2018; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2068, p. 020100. [Google Scholar]

- Klęba, J.; Zheng, K.; Duraczy’nska, D.; Marzec, M.; Fedyna, M.; Mokrzycki, J. Insights into HKUST-1 Metal-Organic Framework’s morphology and physicochemical properties induced by changing the copper (II) salt precursors. Materials 2025, 18, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K.I.; Panayotov, D.A.; Mihaylov, M.Y.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Chakarova, K.K.; Andonova, S.M.; Drenchev, N.L. Power of infrared and Raman spectroscopies to characterize metal-organic frameworks and investigate their interaction with guest molecules. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 1286–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaoping, X.; Wang, C.; Tengfei, Z.; Hu, Q.; Bai, C. Surface acoustic waves (SAWs)-induced synthesis of HKUST-1 crystals with different morphologies and sizes. CrystEngComm 2018, 45, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ghalkhani, M.; Gharagozlou, M.; Sohouli, E.; Marzi Khosrowshahi, E. Preparation of an electrochemical sensor based on a HKUST-1/CoFe2O4/SiO2-modified carbon paste electrode for determination of azaperone. Microchem. J. 2022, 175, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, R.A.; Louis, B.; Baudron, S.A. HKUST-1 MOF in reline deep eutectic solvent: Synthesis and phase transformation. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4145–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.D.; Aranovich, G.L. Adsorption hysteresis in porous solids. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 1998, 205, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Gadipelli, S.; Wood, B.; Ramisetty, K.A.; Stewart, A.A.; Howard, C.A.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F. Characterization of the adsorption site energies and heterogeneous surfaces of porous materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 10104–10137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Tsimnadis, K.; Sebos, I.; Charabi, Y. Investigating the Effect of Pore Size Distribution on the Sorption Types and the Adsorption-deformation characteristics of porous continua: The case of adsorption on carbonaceous materials. Crystals 2024, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Xu, B.; Gao, F.; Gao, F.; Zhao, C. Flower-shaped multiwalled carbon nanotubes@ nickel-trimesic acid MOF composite as a high-performance cathode material for energy storage. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 281, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubbu, V.; Alwin, S.; Mothi, E.M.; Sahaya Shajan, X. TiO2 aerogel–Cu-BTC metal-organic framework composites for enhanced photon absorption. Mater. Lett. 2017, 197, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Zeng, F.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Li, C.; Su, Z. HKUST-1 modified ultrastability cellulose/chitosan composite aerogel for highly efficient removal of methylene blue. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, R.; Tang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhou, L.; Dong, W.; He, D. HKUST-1 and its graphene oxide composites: Finding an efficient adsorbent for SO2 capture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 323, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Cui, M.; Xu, W.; Li, L.; Chen, K. Rapid adsorption of tetracycline in aqueous solution by using MOF-525/graphene oxide composite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 328, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ma, K.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Bai, N. Bioactive effects of nonthermal argon-oxygen plasma on inorganic bovine bone surface. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Niu, Z.; Jin, X.; Tang, L.; Zhu, L. Effect of lithium doping on the structures and CO2 adsorption properties of metal-organic frameworks HKUST-1. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 12865–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubale, A.A.; Ahmed, I.N.; Chen, X.H.; Ding, C.; Hou, G.H.; Guan, R.F.; Xie, M.H. A highly stable metal–organic framework derived phosphorus doped carbon/Cu2O structure for efficient photocatalytic phenol degradation and hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019, 7, 6062–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Hamamoto, Y.; Shiozawa, Y.; Tashima, K.; Fukidome, H.; Matsuda, I. Adsorption of CO2 on graphene: A combined TPD, XPS, and vdW-DF study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 2807–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawowy, M.; Jagódka, P.; Matus, K.; Samojeden, B.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Trawczyński, J.; Łamacz, A. HKUST-1-supported cerium catalysts for CO oxidation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercakir, G.; Aksu, G.O.; Keskin, S. Understanding CO adsorption in MOFs combining atomic simulations and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åhlén, M.; Cheung, O.; Xu, C. Low-concentration CO2 capture using metal–organic frameworks–current status and future perspectives. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Elyazed, A.S.; Ftooh, A.I.; Sun, Y.; Ashry, A.G.; Shaban, A.K.; El-Nahas, A.M.; Yousif, A.M. Solvent-free synthesis of HKUST-1 with abundant defect sites and its catalytic performance in the esterification reaction of oleic acid. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37662–37671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstić, M.; Fink, K.; Sharapa, D.I. The adsorption of small molecules on the copper paddle-wheel: Influence of the multi-reference ground state. Molecules 2022, 27, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Luo, H.; Yuan, Y.; Tong, L.; Chen, B.; Yang, T.; Xiao, J. Equilibrium and dynamic adsorption characteristics of zeolite 5A, LiX, 13X and MOF UTSA-16 adsorbents for hydrogen purification. Inter. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 140, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogler, H.S. Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sangoremi, A.A. Adsorption kinetic models and their applications: A critical review. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2025, 12, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munusamy, K.; Sethia, G.; Patil, D.V.; Rallapalli, P.B.S.; Somani, R.S.; Bajaj, H.C. Sorption of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide on MIL-101 (Cr): Volumetric measurements and dynamic adsorption studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 195, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.D.; Cummings, M.S.; Luebke, R.; Brown, M.S.; Favero, S.; Attfield, M.P.; Petit, C. Screening Metal–Organic frameworks for dynamic CO/N2 separation using complementary adsorption measurement techniques. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 18336–18344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agueda, V.I.; Delgado, J.A.; Uguina, M.A.; Brea, P.; Spjelkavik, A.I.; Blom, R.; Grande, C. Adsorption and diffusion of H2, N2, CO, CH4 and CO2 in UTSA-16 metal-organic framework extrudates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 124, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.A.; Dias, R.O.M.; Lee, U.H.; Chang, J.S.; Ribeiro, A.M.; Ferreira, A.F.P.; Rodrigues, A.E. Adsorption equilibrium of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen on UiO-66 (Zr) _ (COOH)2. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 4724–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Albertsma, J.; Gabriels, D.; Horst, R.; Polat, S.; Snoeks, C.; van der Veen, M.A. Carbon monoxide separation: Past, present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 3741–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britt, D.; Furukawa, H.; Wang, B.; Glover, T.G.; Yaghi, O.M. Highly efficient separation of carbon dioxide by a metal-organic framework replete with open metal sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20637–20640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinata, D.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Aroua, M.K. Production of carbon molecular sieves from palm shell based activated carbon by pore sizes modification with benzene for methane selective separation. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007, 88, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Synthesis of ordered mesoporous carbon molecular sieve and its adsorption capacity for H2, N2, O2, CH4 and CO2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 413, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyoshi, N.; Yogo, K.; Yashima, T. Adsorption characteristics of carbon dioxide on organically functionalized SBA-15. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 84, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.T. Increasing Selective CO2 adsorption on amine-grafted SBA-15 by increasing silanol density. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 21264–21272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchekar, S.; Gaikwad, S.; Kang, S.G.; Han, S. Eco-friendly preparation of K+-doped HKUST-1 metal organic framework for adsorptive collection of CO2 or volatile organic vapors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 346, 131343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wibowo, H.; Zhong, L.; Horttanainen, M.; Wang, Z.; Yu, C.; Yan, M. Cu-BTC-based composite adsorbents for selective adsorption of CO2 from syngas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 279, 119644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Li, S.S.; Xue, D.M.; Liu, X.Q.; Jin, M.M.; Sun, L.B. Incorporation of Cu (II) and its selective reduction to Cu (I) within confined spaces: Efficient active sites for CO adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 8930–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Goyal, N.; Du, T.; He, J.; Li, G.K. Shaping of metal–organic frameworks: A review. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 2927–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandzloch, M.; Bodylska, W.; Trzcinska-Wencel, J.; Golińska, P.; Roszek, K.; Wisniewska, J.; Jaromin, A. Cu-HKUST-1 and hydroxyapatite–the interface of two worlds toward the design of functional materials dedicated to bone tissue regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4646–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R. Integrated technology of CO2 adsorption and catalysis. Catalysts 2025, 15, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, A.J.; Sonibare, J.A.; Adeniran, J.A.; Fakinle, B.S.; Oke, D.O.; Lawal, A.R.; Akeredolu, F.A. Removal of carbon monoxide from an ambient environment using chicken eggshell. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Qu, X.; Xu, D.; Luo, Y. Porous adsorption materials for carbon dioxide capture in industrial flue gas. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 939701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, X.Y.D.; Lee, J.J.C.; Wu, W.Y.; Tao, L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Q.; Bu, J. Advancements in CO2 capture by absorption and adsorption: A comprehensive review. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 81, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorginezhad, S.; Weiland, F.; Chen, Y.; Hussain, S.; Ji, X. Review and analysis of porous adsorbents for effective CO2 capture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 215, 115589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | BMOF2 | BMOF3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %Rectotal | 57% | 54% | ||

| Gases | CO | CO2 | CO | CO2 |

| %Reci | 66% | 49% | 13% | 57% |

| Material | Gas | qe (mmol/g) | Temperature (K) | Pressure (bar) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMOF3 BMOF2 | CO | 0.61 0.62 | 298 | 1 | This study |

| Zeolite Y (proton form, Si/Al = 5) | 0.21 | 303 | 1 | [74] | |

| Zeolite Y (Na+ form, Si/Al = 2.4) | 0.48 | 293 | 0.6 | ||

| Cu(I)/γ-Al2O3 (supported CuCl; CO adsorption by interaction with Cu(I)) | 0.45 | 298 | 1 | ||

| HKUST-1 | 0.30 | 298 | 1 | ||

| Cu(II) porous coordination polymer (PCP) (Cu(aip)) | 7.15 | 298 | 1 | ||

| BMOF3 BMOF2 | CO2 | 0.53 0.75 | 298 | 1 | This study |

| Mg-MOF-74 | 0.20 | 298 | 1 | [75] | |

| Chemical activated carbon | 0.68 | 298 | 1 | [76] | |

| Ordered mesoporous carbon | 0.41 | 298 | 1 | [77] | |

| APS/SBA-15(III) | 0.66 | 333 | 1 | [78] | |

| Zn-MOF-74 | 0.08 | 213 | 1 | [75] | |

| Mesoporous silica SBA-15 | 1.6 | 298 | 0.15 | [79] | |

| MIL-101(Cr) granules | 1.63 | 313 | 1 | [70] | |

| HKUST-1 | 6.19 | 298 | 1 | [80] | |

| Mg-HKUST- 1@MWCNT | 3.63 | 298 | 1 | [81] | |

| Li-HKUST-1 | 4.57 | 298 | 1 | [59] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toledo-Jaldin, H.P.; Blanco-Flores, A.; Pacheco, M.; Valdivia-Barrientos, R.; Pacheco, J.O. Uncarbonized Bovine Bone/MOF Composite as a Hybrid Green Material for CO and CO2 Selective Adsorption. Separations 2026, 13, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010011

Toledo-Jaldin HP, Blanco-Flores A, Pacheco M, Valdivia-Barrientos R, Pacheco JO. Uncarbonized Bovine Bone/MOF Composite as a Hybrid Green Material for CO and CO2 Selective Adsorption. Separations. 2026; 13(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleToledo-Jaldin, Helen Paola, Alien Blanco-Flores, Marquidia Pacheco, Ricardo Valdivia-Barrientos, and Joel O. Pacheco. 2026. "Uncarbonized Bovine Bone/MOF Composite as a Hybrid Green Material for CO and CO2 Selective Adsorption" Separations 13, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010011

APA StyleToledo-Jaldin, H. P., Blanco-Flores, A., Pacheco, M., Valdivia-Barrientos, R., & Pacheco, J. O. (2026). Uncarbonized Bovine Bone/MOF Composite as a Hybrid Green Material for CO and CO2 Selective Adsorption. Separations, 13(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010011