Sustainable Luffa cylindrica Bio-Sponge Immobilized with Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 for Efficient Azo Dye Removal from Textile Effluents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dye Stock Solution

2.2. Microorganisms, Media, and Culture Conditions

2.3. Fungal Biomass Production and Immobilization in Luffa cylindrica

2.4. Dye Decolorization Studies

2.5. Factorial Design

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

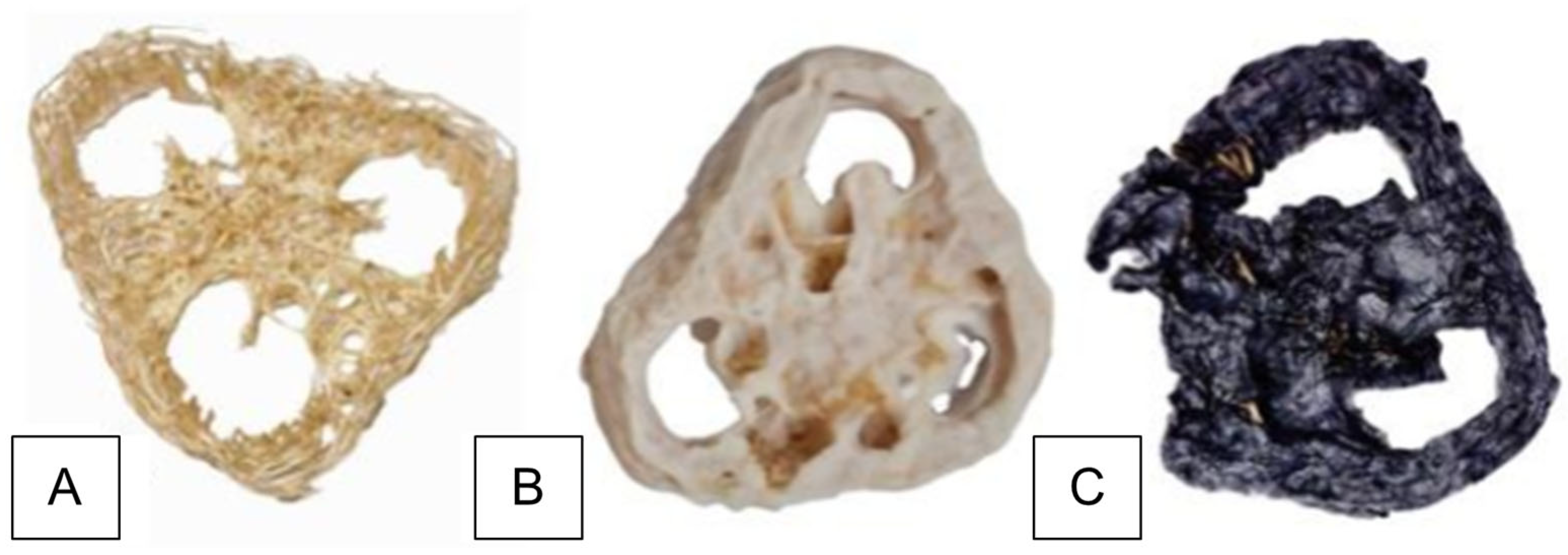

3.1. Immobilization of Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 on Luffa cylindrica

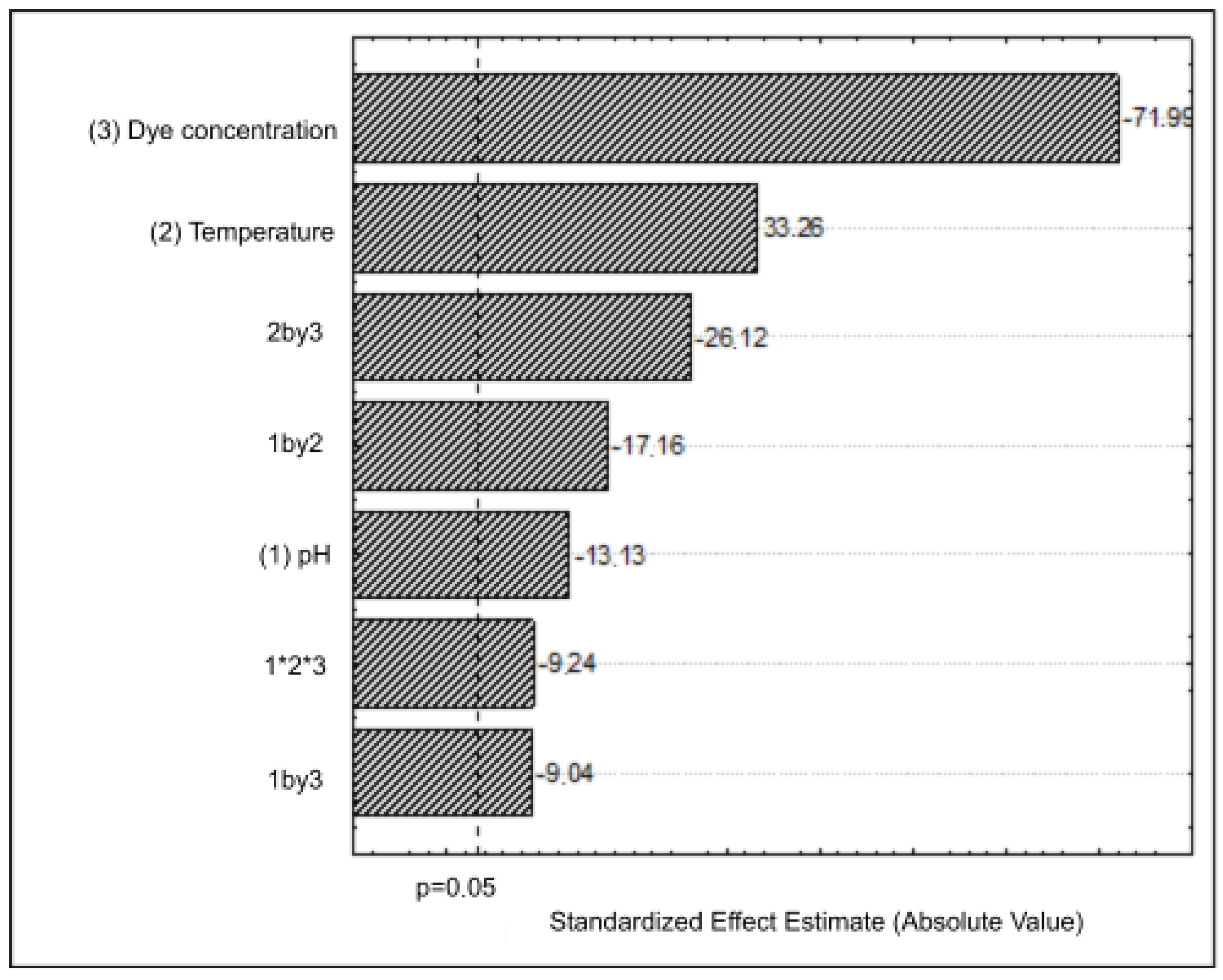

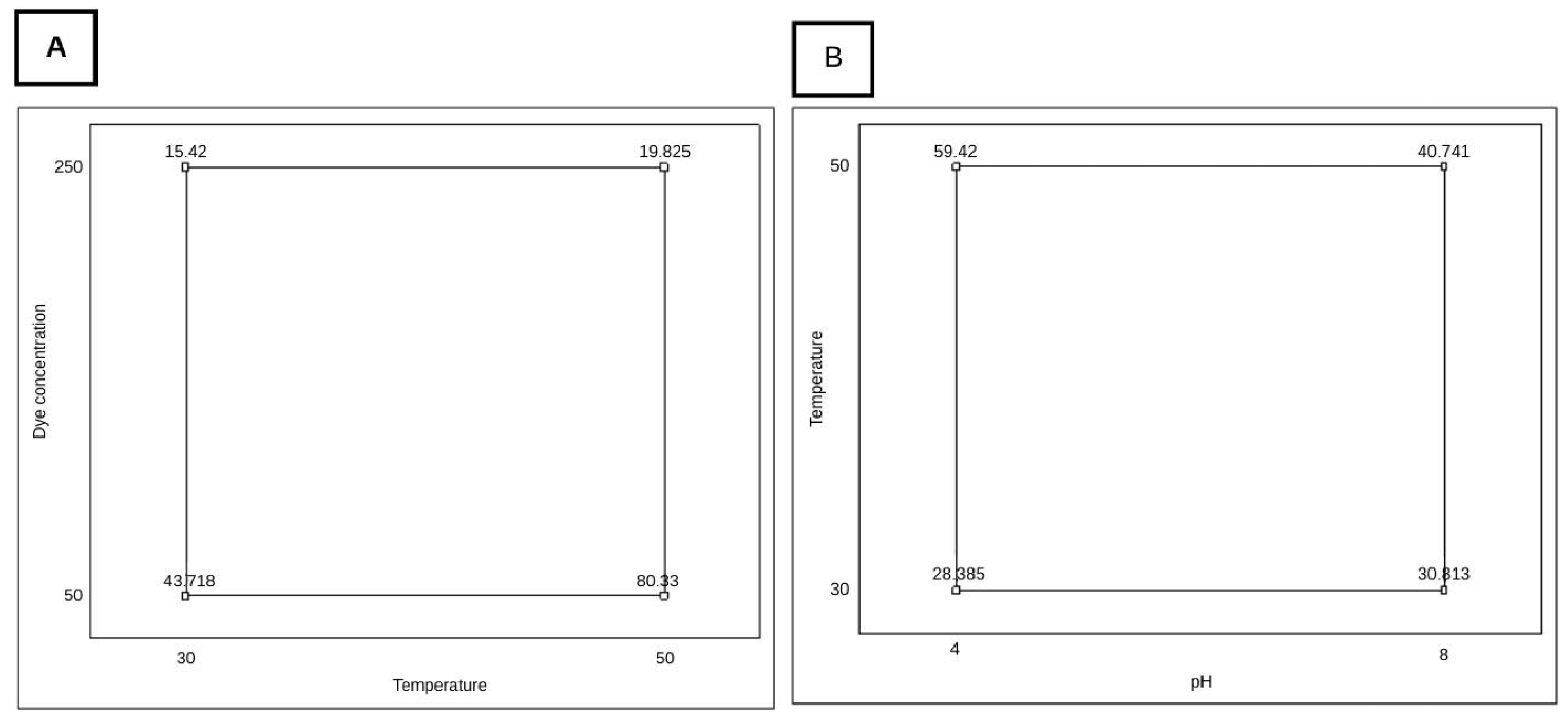

3.2. Optimization of DB22 Dye Decolorization

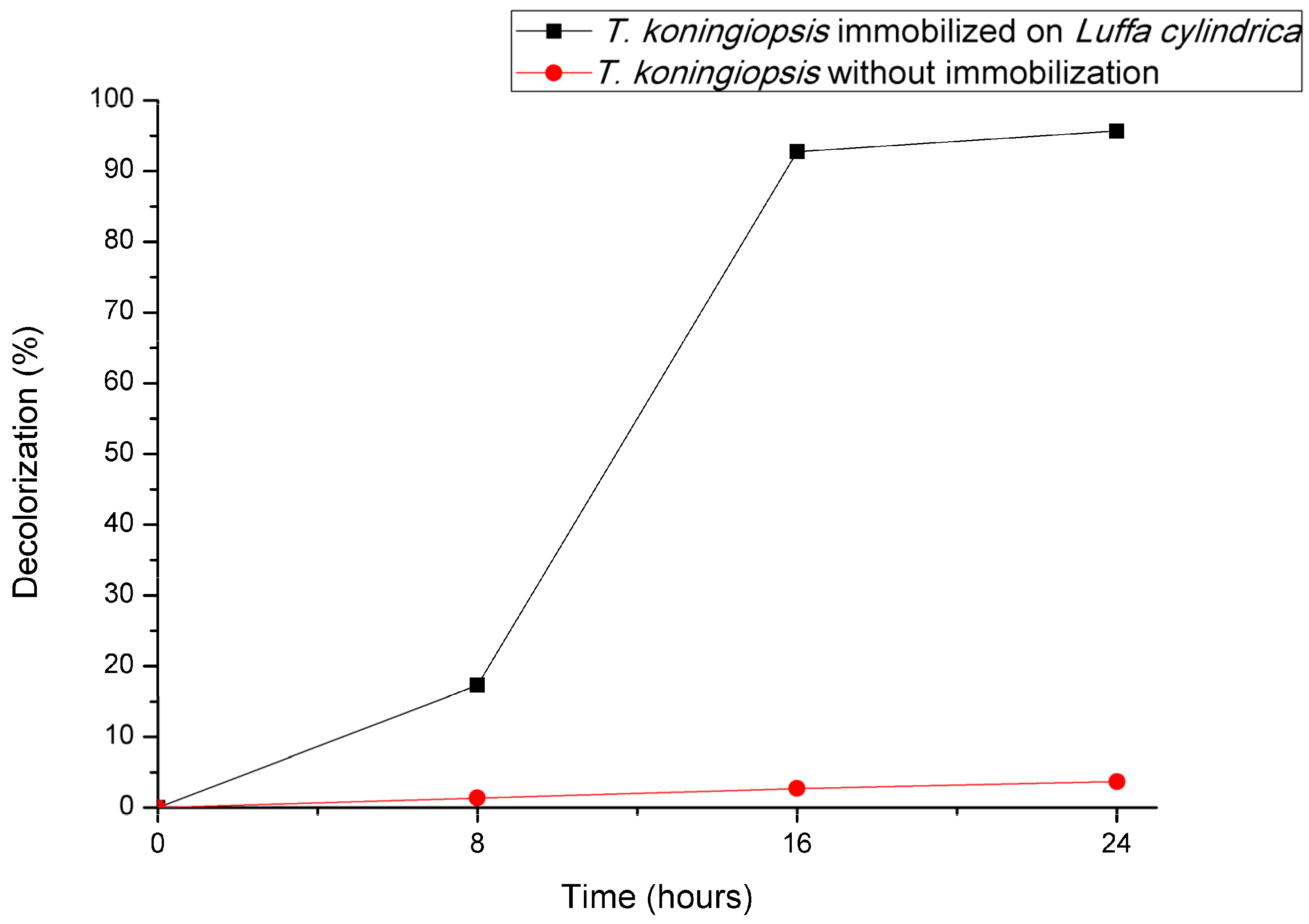

3.3. Comparison of DB22 Decolorization Efficiency with and Without Fungal Immobilization on Luffa cylindrica

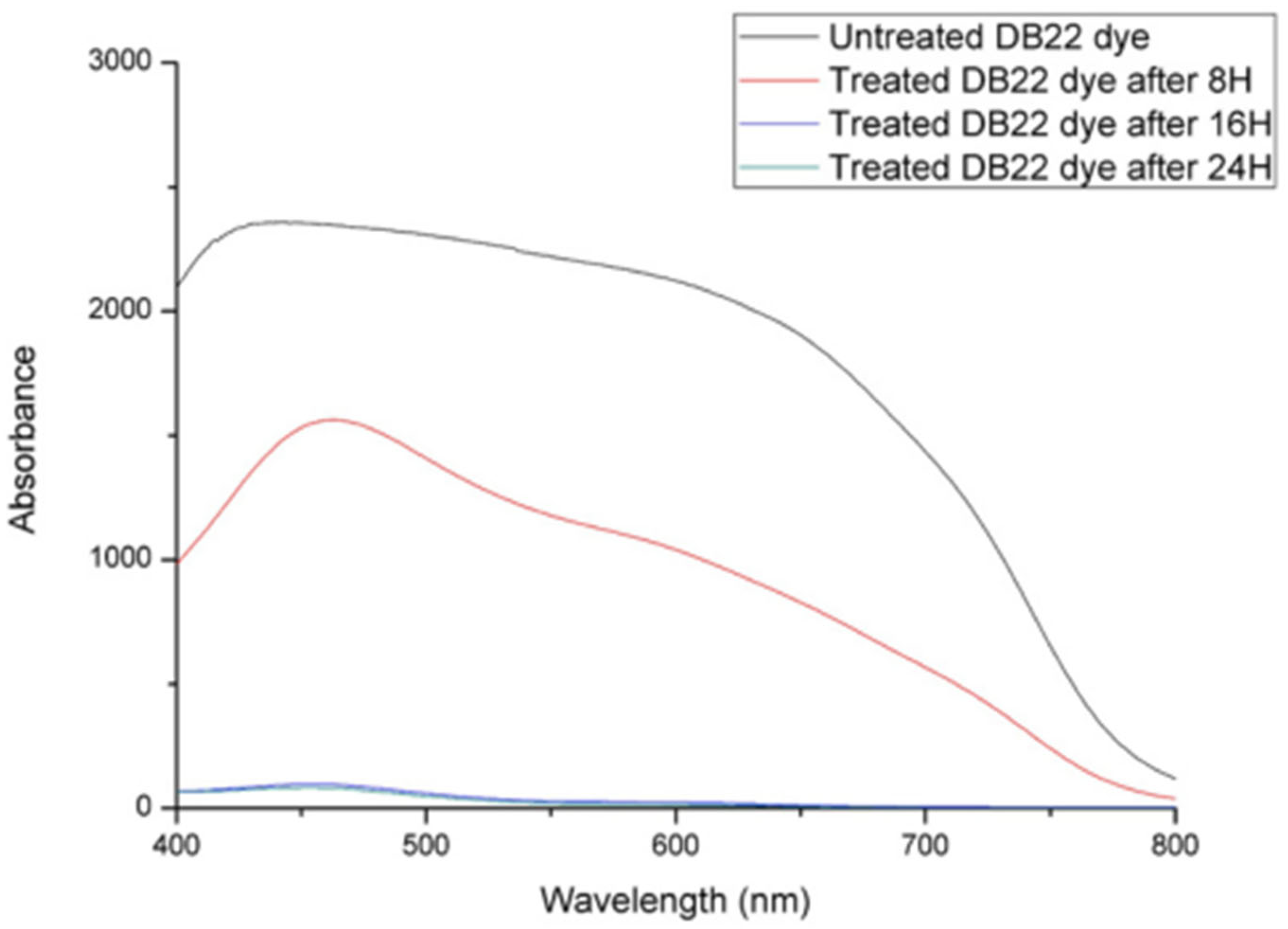

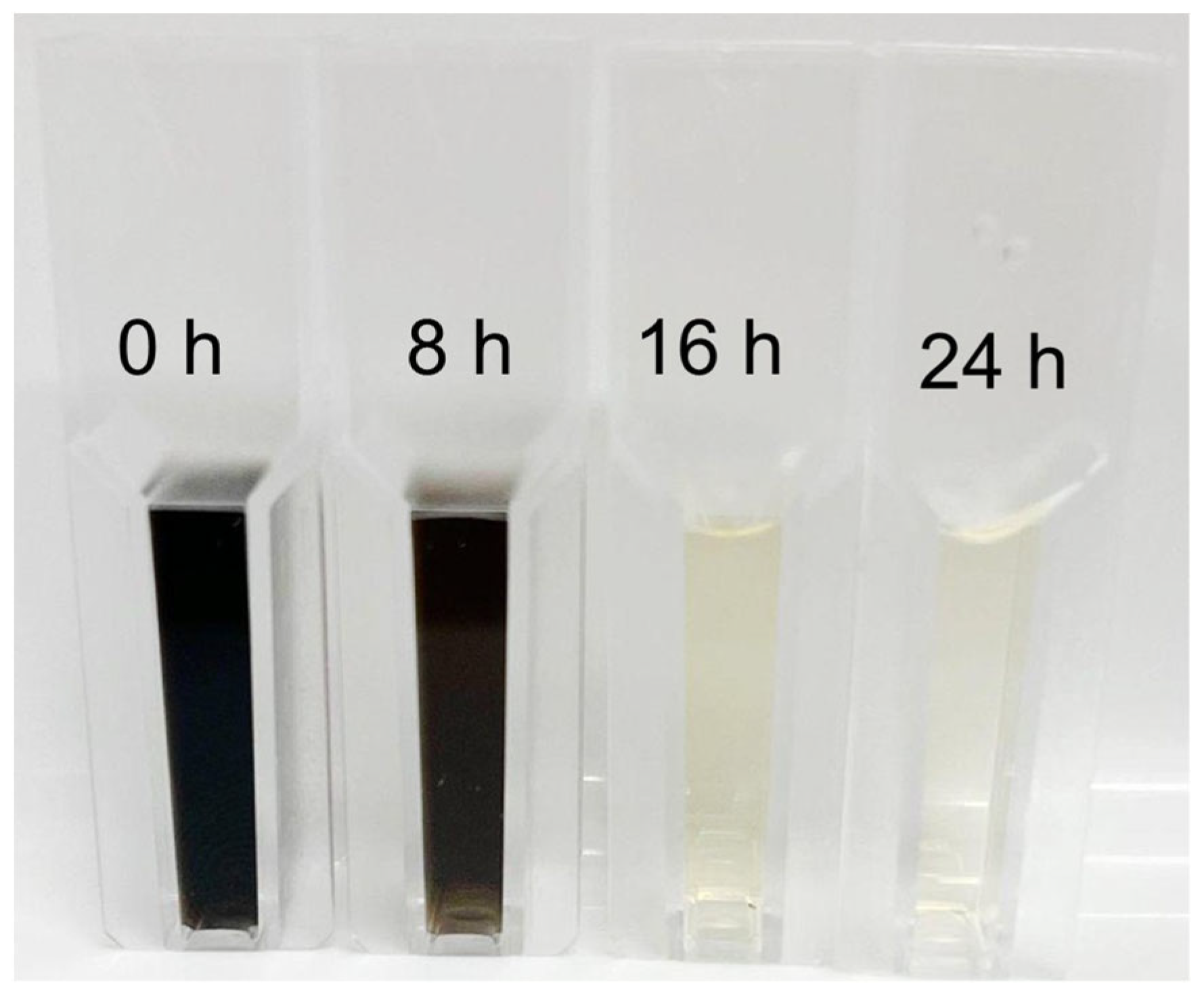

3.4. Dye Analysis by UV–Visible Spectroscopy

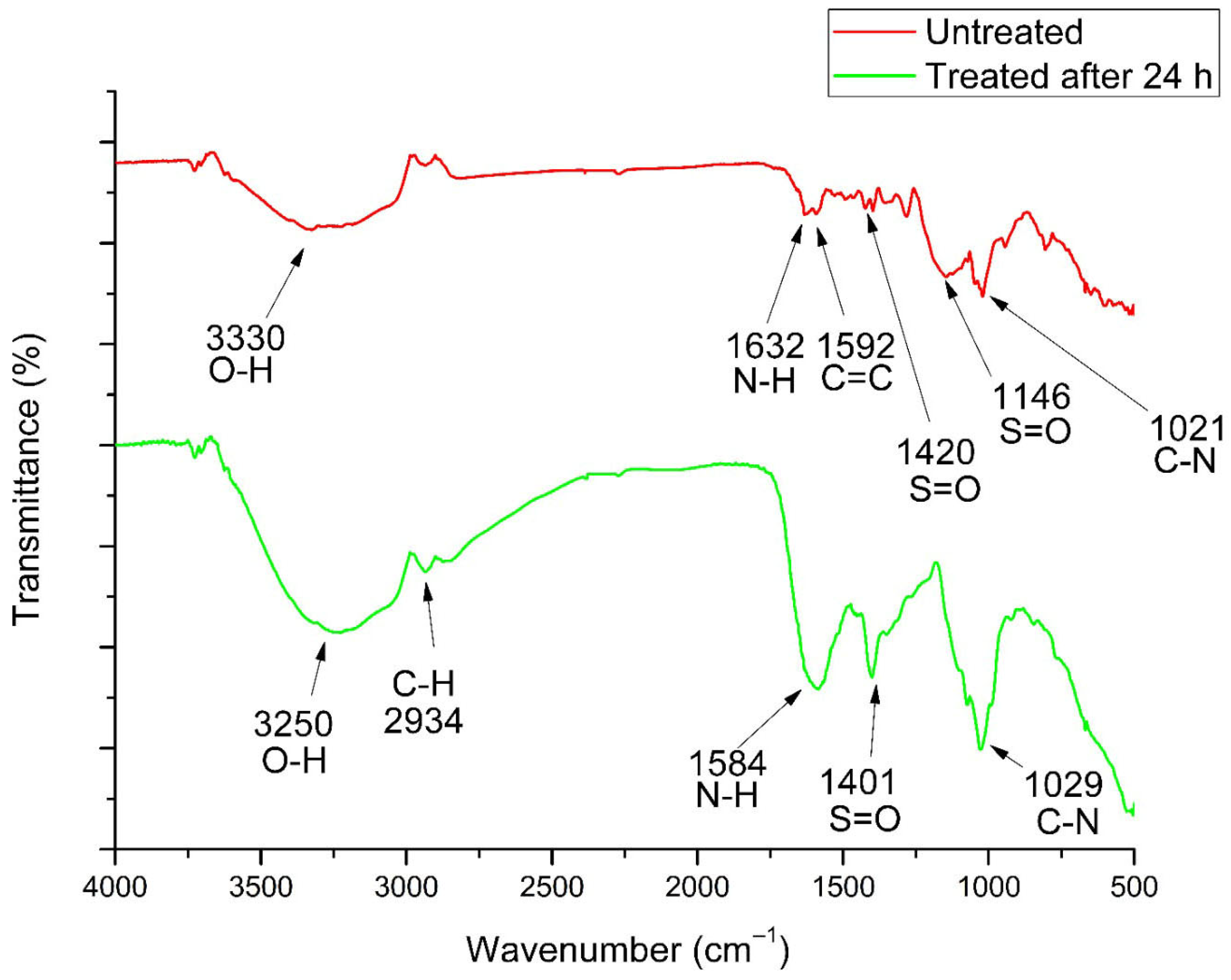

3.5. Physicochemical Characterization Through FTIR

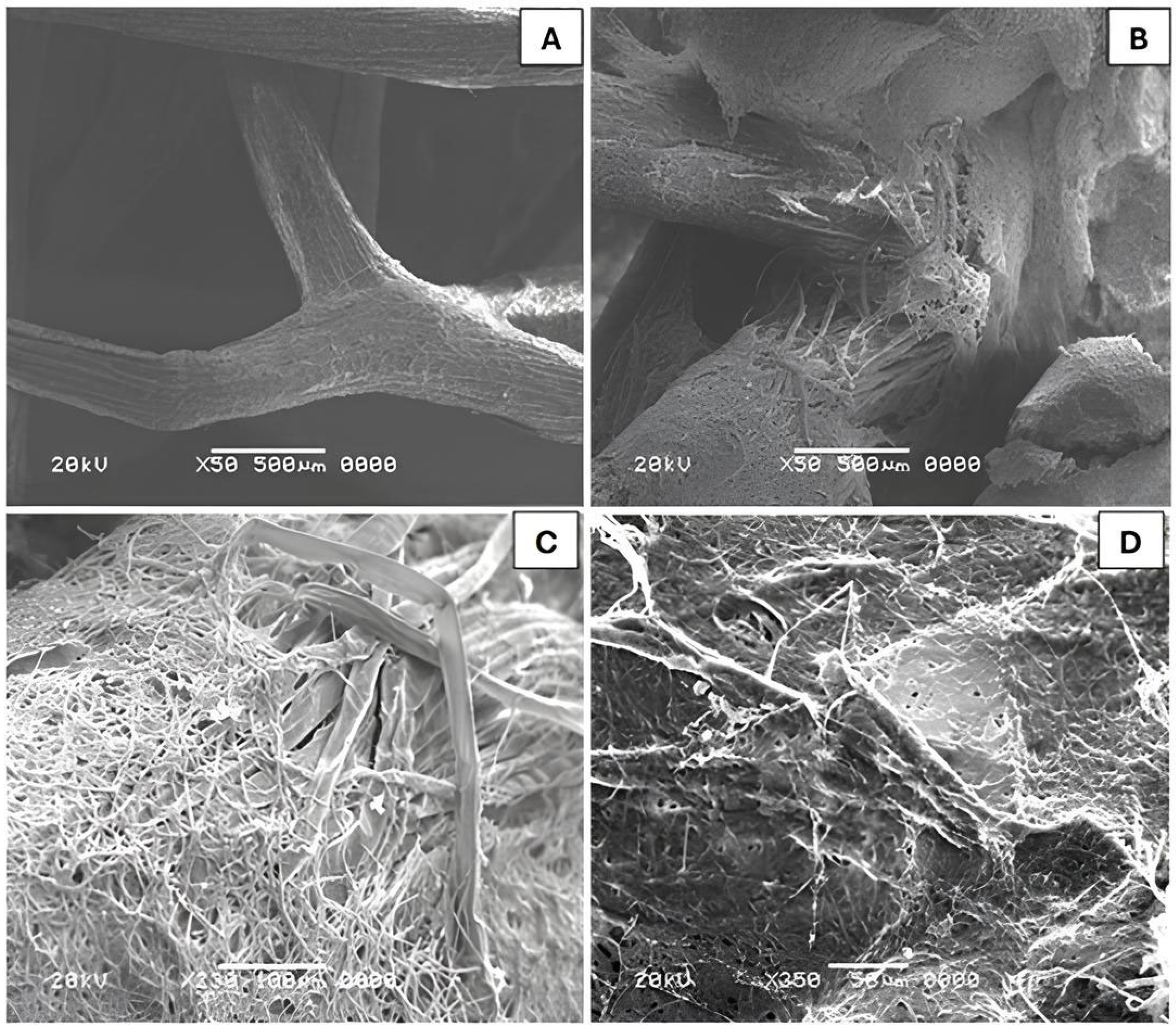

3.6. Decolorization of DB22 Dye on Immobilized Fungal Biomass—Scanning Electron Microscopy Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Castro-Pardo, M.; Fernández Martínez, P.; Pérez Zabaleta, A.; Azevedo, J.C. Dealing with Water Conflicts: A Comprehensive Review of MCDM Approaches to Manage Freshwater Ecosystem Services. Land 2021, 10, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, C.K. Environmental Pollution Indices: A Review on Concentration of Heavy Metals in Air, Water, and Soil near Industrialization and Urbanisation. Discov. Environ. 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P. Recent Advances in the Remediation of Textile-Dye-Containing Wastewater: Prioritizing Human Health and Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiano, V.; De Marco, I. Removal of Azo Dyes from Wastewater through Heterogeneous Photocatalysis and Supercritical Water Oxidation. Separations 2023, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Derami, H.K.; Rong, Z.; Nguyen, T. Recent Advances for Dyes Removal Using Novel Adsorbents: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Textile Dye Wastewater Characteristics and Constituents of Synthetic Effluents: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shaad, K.; Vollmer, D.; Ma, C. Treatment of Textile Wastewater Using Advanced Oxidation Processes—A Critical Review. Water 2021, 13, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y.; Routula, A.; Patwardhan, R.R. Efficiency of Various Recent Wastewater Dye Removal Methods: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Singh, S.; Pathak, S.; Kasaudhan, J.; Mishra, A.; Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Singh, P.K.; et al. Recent Strategies for the Remediation of Textile Dyes from Wastewater: A Systematic Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppan, N.; Padman, M.; Mahadeva, M.; Srinivasan, S.; Devarajan, R. A Comprehensive Review of Sustainable Bioremediation Techniques: Eco Friendly Solutions for Waste and Pollution Management. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Zahoor, M.; Naeem, M.; Ul Islam, N.; Bari Shah, A.; Shahzad, B. Bacterial oxidoreductive enzymes as molecular weapons for the degradation and metabolism of the toxic azo dyes in wastewater: A review. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 2023, 237, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Naeem, M.; Zahoor, M.; Rahim, A.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Oyekanmi, A.A.; Shah, A.B.; Mahnashi, M.H.; Al Ali, A.; Jalal, N.A.; et al. Biodegradation of Azo Dye Methyl Red by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Optimization of Process Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.G.D.; Silva, R.L.A.; Cardoso, K.B.B.; Brito Júnior, J.J.R.T.; Ferreira, K.R.C.; Nascimento, T.P.; Brandão-Costa, R.M.P.; Silva, M.V.; Porto, A.L.F. Exploring Aspergillus Biomass for Fast and Effective Direct Black 22-Dye Removal. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Ambient. 2024, 59, e2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbins-Martínez, M.; Juárez-Hernández, J.; López-Domínguez, J.Y.; Nava-Galicia, S.B.; Martínez-Tozcano, L.J.; Juárez-Atonal, R.; Díaz-Godinez, G. Potential Application of Fungal Biosorption and/or Bioaccumulation for the Bioremediation of Wastewater Contamination: A Review. J. Environ. Biol. 2023, 44, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Przystaś, W.; Dave, B. Myco-Remediation of Synthetic Dyes: A Comprehensive Review on Contaminant Alleviation Mechanism, Kinetic Study and Toxicity Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Tas, S.K.; Sayin, F.; Akar, T.; Akar, S.T. Green Biosourced Composite for Efficient Reactive Dye Decontamination: Immobilized Gibberella fujikuroi on Maize Tassel Biomatrix. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 25836–25848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.; De Conto, J.F.; Borges, G.R.; Egues, S.M. Luffa cylindrica as a Biosorbent in Wastewater Treatment Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Cellulose 2024, 31, 10115–10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Moreno-García, J.; Barzee, T.J. Filamentous Fungal Pellets as Versatile Platforms for Cell Immobilization: Developments to Date and Future Perspectives. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundir, A.; Thakur, M.S.; Prakash, S.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, N.; Parameswari, E.; He, Z.; Nam, S.; Thakur, M.; Puri, S.; et al. Fungi as Versatile Biocatalytic Tool for Treatment of Textile Wastewater Effluents. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraib, Q.; Shafique, M.; Jabeen, N.; Naz, S.A.; Nawaz, H.R.; Solangi, B.; Zubair, A.; Sohail, M. Luffa cylindrica Immobilized with Aspergillus terreus QMS-1: An Efficient and Cost-Effective Strategy for the Removal of Congo Red Using Stirred Tank Reactor. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, S.M.; Kato, M.T.; Florencio, L.; Gavazza, S. Influence of Redox Mediators and Electron Donors on the Anaerobic Removal of Color and Chemical Oxygen Demand from Textile Effluent. Clean—Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriharsha, D.V.; Kumar, L.; Savitha, J. Immobilized Fungi on Luffa cylindrica: An Effective Biosorbent for the Removal of Lead. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.D.; Nascimento, V.R.S.; Meneses, D.B.; Vilar, D.S.; Torres, N.H.; Leite, M.S.; Ferreira, L.F.R. Fungal Biosynthesis of Lignin-Modifying Enzymes from Pulp Wash and Luffa cylindrica for Azo Dye RB5 Biodecolorization Using Modeling by Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Network. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 399, 123094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.; He, H.; Liang, M.; Tu, Z.; Zhu, H. Immobilization of Biomass Materials for Removal of Refractory Organic Pollutants from Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Przystaś, W.; Turczyn, R.; Jureczko, M. Enhanced Biosorption of Triarylmethane Dyes by Immobilized Trametes versicolor and Pleurotus ostreatus: Optimization, Kinetics, and Reusability. Water 2025, 17, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajhans, G.; Barik, A.; Sen, S.K.; Raut, S. Degradation of Dyes by Fungi: An Insight into Mycoremediation. BioTechnologia 2021, 102, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Kinetics and Characteristics Studies on Biosorption of Acid Red 18 from Aqueous Solution by the Acid-Treated Mycelia Pellets of Penicillium janthinellum. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 167, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Cihangir, N.; Idil, N.; Aracagök, Y.D. Adsorption of Azo Dye by Biomass and Immobilized Yarrowia lipolytica: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.T.; Zohaib, M.; Rauf, N.; Tahir, S.S.; Parvez, S. Biosorption Characteristics of Aspergillus fumigatus for the Decolorization of Triphenylmethane Dye Acid Violet 49. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 3133–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, H.D.; Réda Yeddou, A.; Bouras, N.; Chergui, A.; Favier, L.; Amrane, A.; Dizge, N. Biosorption of Cationic and Anionic Dyes Using the Biomass of Aspergillus parasiticus CBS 100926T. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeela; Khan, S.A.; Mehmood, S.; Shabbir, S.B.; Ali, S.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Albeshr, M.F.; Hamayun, M. Efficacy of Fungi in the Decolorization and Detoxification of Remazol Brilliant Blue Dye in Aquatic Environments. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, B.; Alemu, T.; Ebsa, G. Screening and Identification of Microbes from Polluted Environment for Azo Dye (Turquoise Blue) Decolorization. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchieri, D.; Mangiagalli, M.; Martani, F.; Butti, P.; Lotti, M.; Serra, I.; Branduardi, P. A Novel Laccase from Trametes polyzona with High Performance in the Decolorization of Textile Dyes. AMB Express 2024, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Latif, A.S.A.; Zohri, A.-N.A.; El-Aref, H.M.; Mahmoud, G.A.-E. Kinetic Studies on Optimized Extracellular Laccase from Trichoderma harzianum PP389612 and Its Capabilities for Azo Dye Removal. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktaviani, M.; Damin, B.C.S.; Suryanegara, L.; Yanto, D.H.Y.; Watanabe, T. Immobilization of fungal mycelial and laccase from Trametes hirsuta EDN082 in alginate-cellulose beads and its use in Remazol Brilliant Blue R dye decolorization. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argumedo-Delira, R.; Gómez-Martínez, M.J.; Uribe-Kaffure, R. Trichoderma Biomass as an Alternative for Removal of Congo Red and Malachite Green Industrial Dyes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, M.; LR, P.; Jindal, M.K. Eco-friendly biosorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater: A comprehensive review. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 4029–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Kamal, K.H.; Farroh, K.; Ali, E.F.; Hassan, M.A. Development of Fast and High-Efficiency Sponge-Gourd Fibers (Luffa cylindrica)/Hydroxyapatite Composites for Removal of Lead and Methylene Blue. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulos, I.; Pashalidis, I. Environmental applications of Luffa cylindrica-based adsorbents. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 319, 114127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Pan, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Salah Zene, A.; Tian, Y. Biosorption of Congo Red from Aqueous Solutions Based on Self-Immobilized Mycelial Pellets: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Thermodynamic Studies. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 24601–24612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, H.D.; Yeddou, A.R.; Bouras, N.; Hellel, D.; Holtz, M.D.; Sabaou, N.; Chergui, A.; Nadjemi, B. Biosorption of Congo red dye by Aspergillus carbonarius M333 and Penicillium glabrum Pg1: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Boddu, V.M.; Krishnaiah, A. Biosorption of phenolic compounds by trametes versicolor polyporus fungus. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2009, 27, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K.; Knözinger, H. Identification and Characterization of Surface Hydroxyl Groups by Infrared Spectroscopy. Adv. Catal. 2014, 57, 99–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürses, A.; Açıkyıldız, M.; Güneş, K.; Gürses, M.S. Dyes and Pigments: Their Structure and Properties. In Dyes Pigments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Iyun, O.R.A.; Egbe, J.O.; Kantiok, G.Y. Substituent Effects on Absorption Spectra of 7-Amino-4-Hydroxynaphthalene-2-Sulfonic Acid-Based Dyes. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2020, 24, 124–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, R.; Singh, P. Structure and Properties of Dyes and Pigments. In Dyes and Pigments—Novel Applications and Waste Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Gita, S.; Singh, R.; Kaushik, A.; Vats, R. Adsorption-Linked Fungal Degradation Process for Complete Removal of Lanasyn Olive Dye Using Chemically Valorized Sugarcane Bagasse. Waste Manag. Bull. 2023, 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.J.R.; Corso, C.R. Comparative Study of Toxicity of Azo Dye Procion Red MX-5B Following Biosorption and Biodegradation Treatments with the Fungi Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus terreus. Chemosphere 2014, 112, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Thakur, S.; Pathania, D.; Sharma, G. Exploring Fungal-Mediated Solutions and Its Molecular Mechanistic Insights for Textile Dye Decolorization. Chemosphere 2024, 360, 142370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmode, M.S.; Kardile, A.V.; Mene, R.U.; Abhyankar, P.S.; Rout, S.; Sahoo, D.K.; Patil, N.N. Synthesis and Characterization of Fungal and Luffa Sponge Biocomposite Sorbent for the Removal of Acetaminophen. Discov. Water 2025, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieniuk, B.; Małajowicz, J.; Jasińska, K.; Wierzchowska, K.; Uğur, Ş.; Fabiszewska, A. Agri-Food and Food Waste Lignocellulosic Materials for Lipase Immobilization as a Sustainable Source of Enzyme Support—A Comparative Study. Foods 2024, 13, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małajowicz, J.; Gołębiowska, A.; Knotek, A. Immobilization of Whole-Cell Yarrowia lipolytica Catalysts on the Surface of Luffa cylindrica Sponge. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2022, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasamy, A.; Sundarabal, N. Biosorption of an Azo Dye by Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma sp. Fungal Biomasses. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrósio, S.T.; Vilar Júnior, J.C.; Da Silva, C.A.A.; Okada, K.; Nascimento, A.E.; Longo, R.L.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. A Biosorption Isotherm Model for the Removal of Reactive Azo Dyes by Inactivated Mycelia of Cunninghamella elegans UCP542. Molecules 2012, 17, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Figueroa, M.G.; Romero, R.J.; Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-Torres, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Bolio-López, G.I.; Arias-Ataide, D.M.; Torres-Islas, Á.; Valladares-Cisneros, M.G. Removal of Azo Dyes from Water on a Large Scale Using a Low-Cost and Eco-Friendly Adsorbent. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Singh, D.; Singh, R.S.; Mishra, V.; Kumar, M.; Giri, B.S. Performance Study of the Bioreactor for the Biodegradation of Methyl Orange Dye by Luffa-Immobilized Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Kinetic Studies: A Sustainable Approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 27, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Coded Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | +1 | |

| 4 | 6 | 8 |

| 30 | 40 | 50 |

| 50 | 150 | 250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dias, P.H.S.d.F.; Silva, R.L.A.; Neves, A.G.D.; Andrade, A.F.M.d.; Cardoso, K.B.B.; Miranda, M.E.L.C.d.; Macêdo, D.C.d.S.; Lino, L.H.S.; Cunha, M.N.C.d.; Santos, A.M.G.; et al. Sustainable Luffa cylindrica Bio-Sponge Immobilized with Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 for Efficient Azo Dye Removal from Textile Effluents. Separations 2026, 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010001

Dias PHSdF, Silva RLA, Neves AGD, Andrade AFMd, Cardoso KBB, Miranda MELCd, Macêdo DCdS, Lino LHS, Cunha MNCd, Santos AMG, et al. Sustainable Luffa cylindrica Bio-Sponge Immobilized with Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 for Efficient Azo Dye Removal from Textile Effluents. Separations. 2026; 13(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleDias, Paulo Henrique Silva de França, Raphael Luiz Andrade Silva, Anna Gabrielly Duarte Neves, André Filipe Marinho de Andrade, Kethylen Barbara Barbosa Cardoso, Maria Eduarda Luiz Coelho de Miranda, Daniel Charles dos Santos Macêdo, Luiz Henrique Svintiskas Lino, Márcia Nieves Carneiro da Cunha, Alice Maria Gonçalves Santos, and et al. 2026. "Sustainable Luffa cylindrica Bio-Sponge Immobilized with Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 for Efficient Azo Dye Removal from Textile Effluents" Separations 13, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010001

APA StyleDias, P. H. S. d. F., Silva, R. L. A., Neves, A. G. D., Andrade, A. F. M. d., Cardoso, K. B. B., Miranda, M. E. L. C. d., Macêdo, D. C. d. S., Lino, L. H. S., Cunha, M. N. C. d., Santos, A. M. G., Lima, M. A. B. d., Nascimento, T. P., Porto, A. L. F., & Costa, R. M. P. B. (2026). Sustainable Luffa cylindrica Bio-Sponge Immobilized with Trichoderma koningiopsis UFPIT07 for Efficient Azo Dye Removal from Textile Effluents. Separations, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010001