Design, Simulation, and Parametric Analysis of an Ultra-High Purity Phosphine Purification Process with Dynamic Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

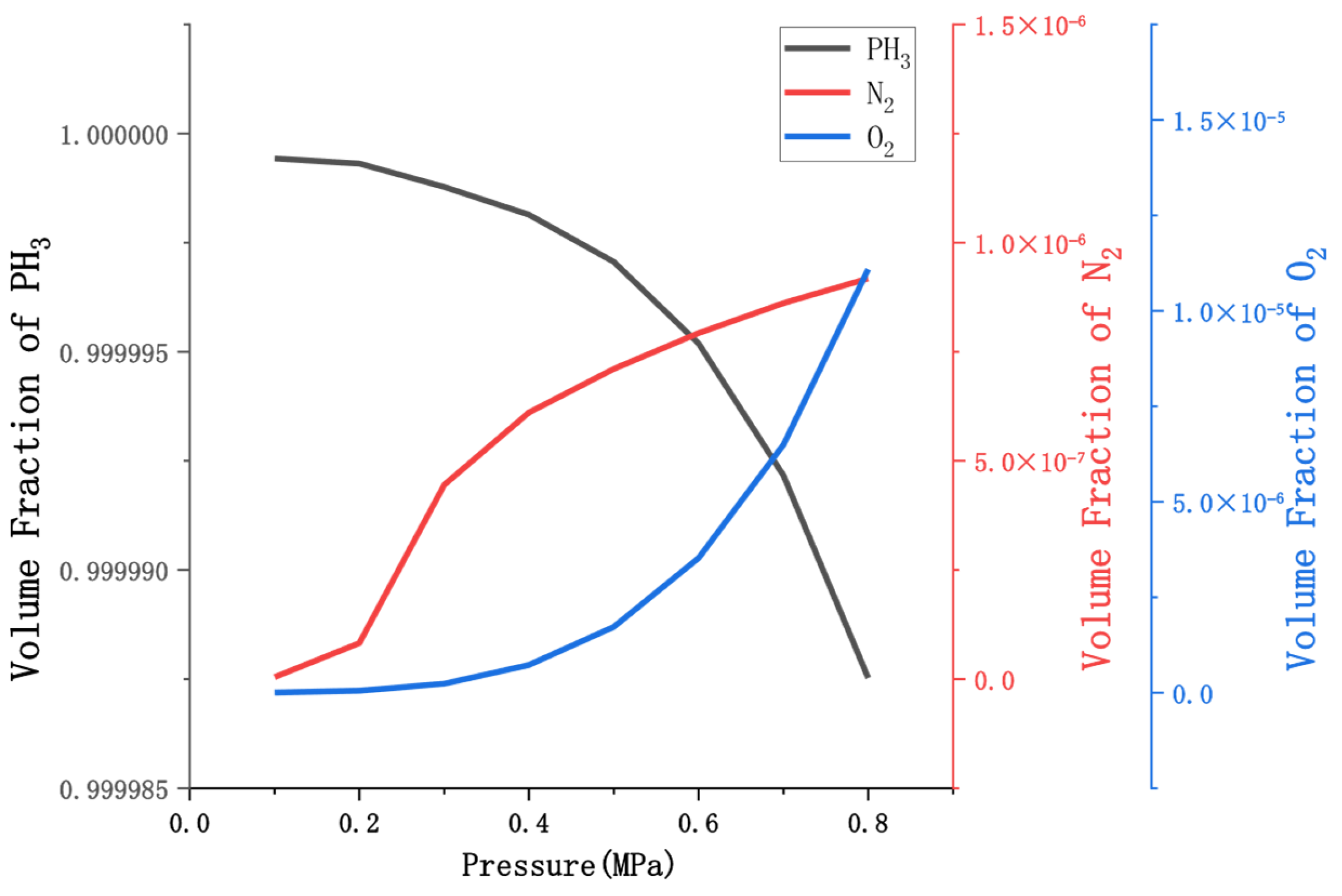

2. Process Design and Model Validation

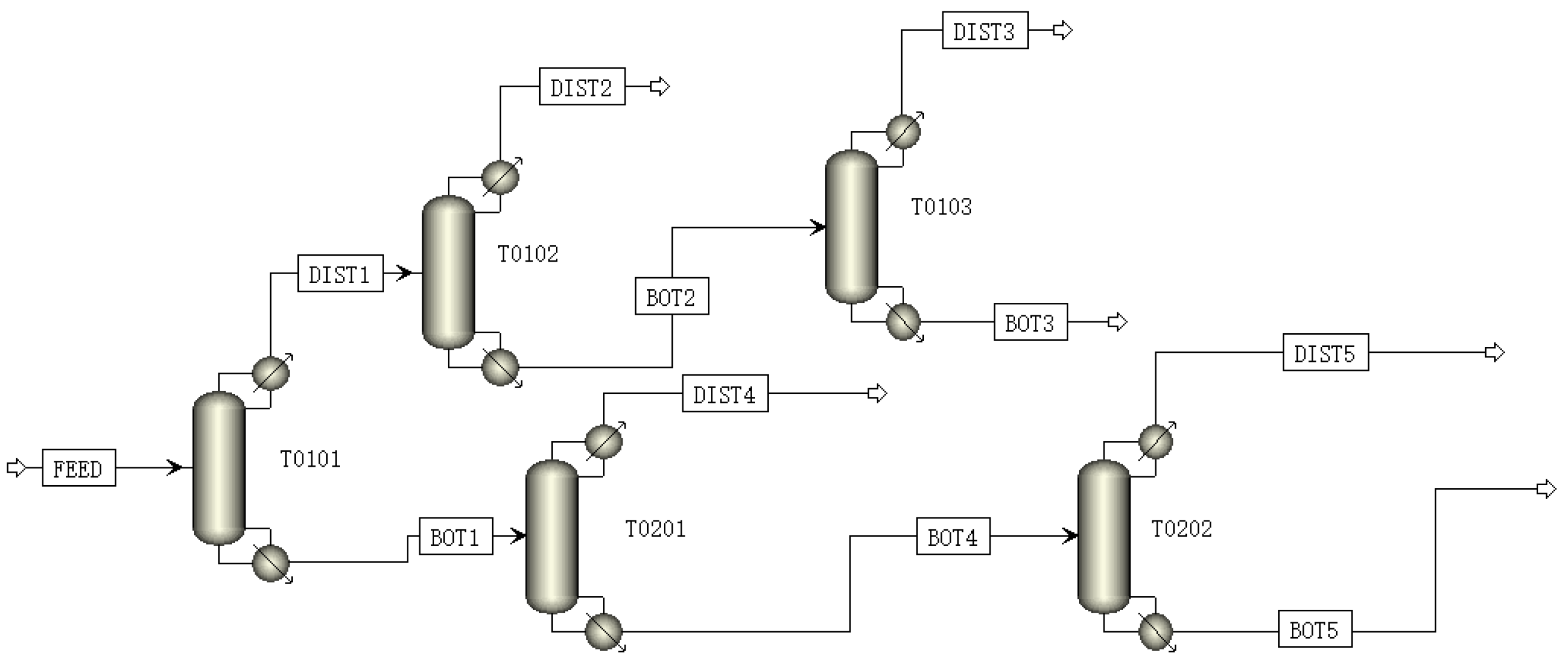

2.1. Process Design

- (1)

- Only impurities that are more prevalent or difficult to remove in the production process are considered, while other impurities, dust, and gases are ignored.

- (2)

- The system is assumed to operate in a steady state, and pressure drops within the tower and pipelines are ignored.

- (3)

- The heat transfer process is assumed to be adiabatic, and equipment heat dissipation is not considered.

- (4)

- For all rectifying columns, the Murphree Tray Efficiency (MTE) is assumed to be 100%, i.e., the simulation is based on “theoretical plates” rather than actual trays.

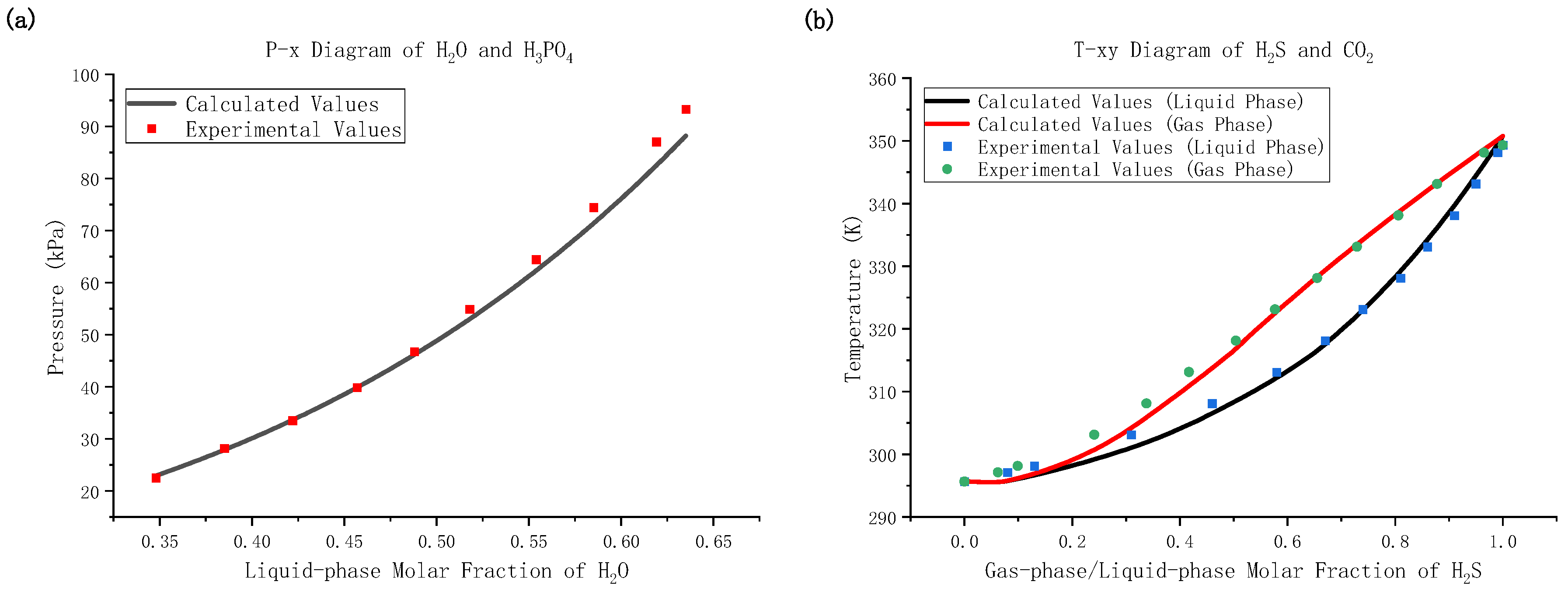

2.2. Model Validation

3. Sensitivity Analysis

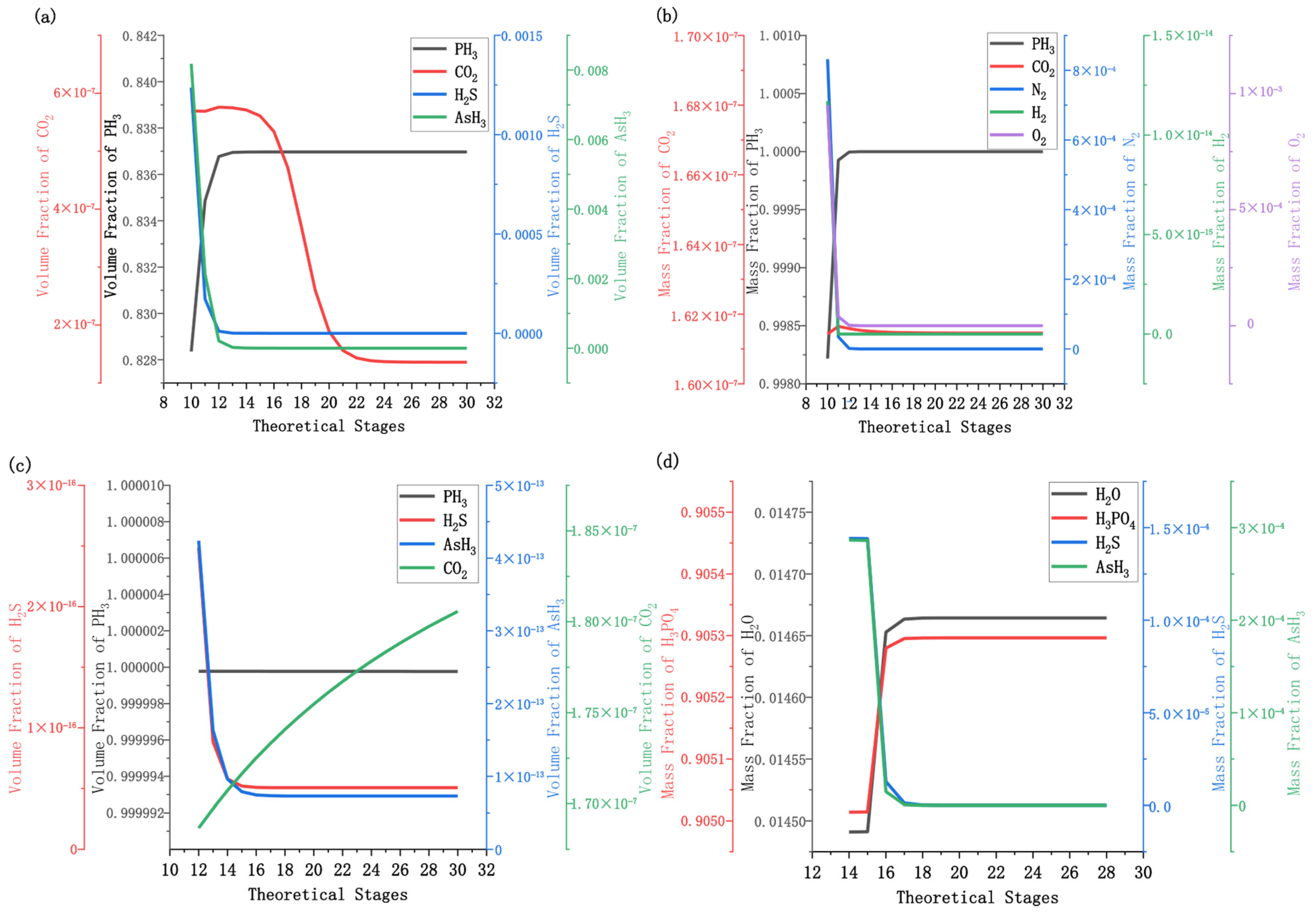

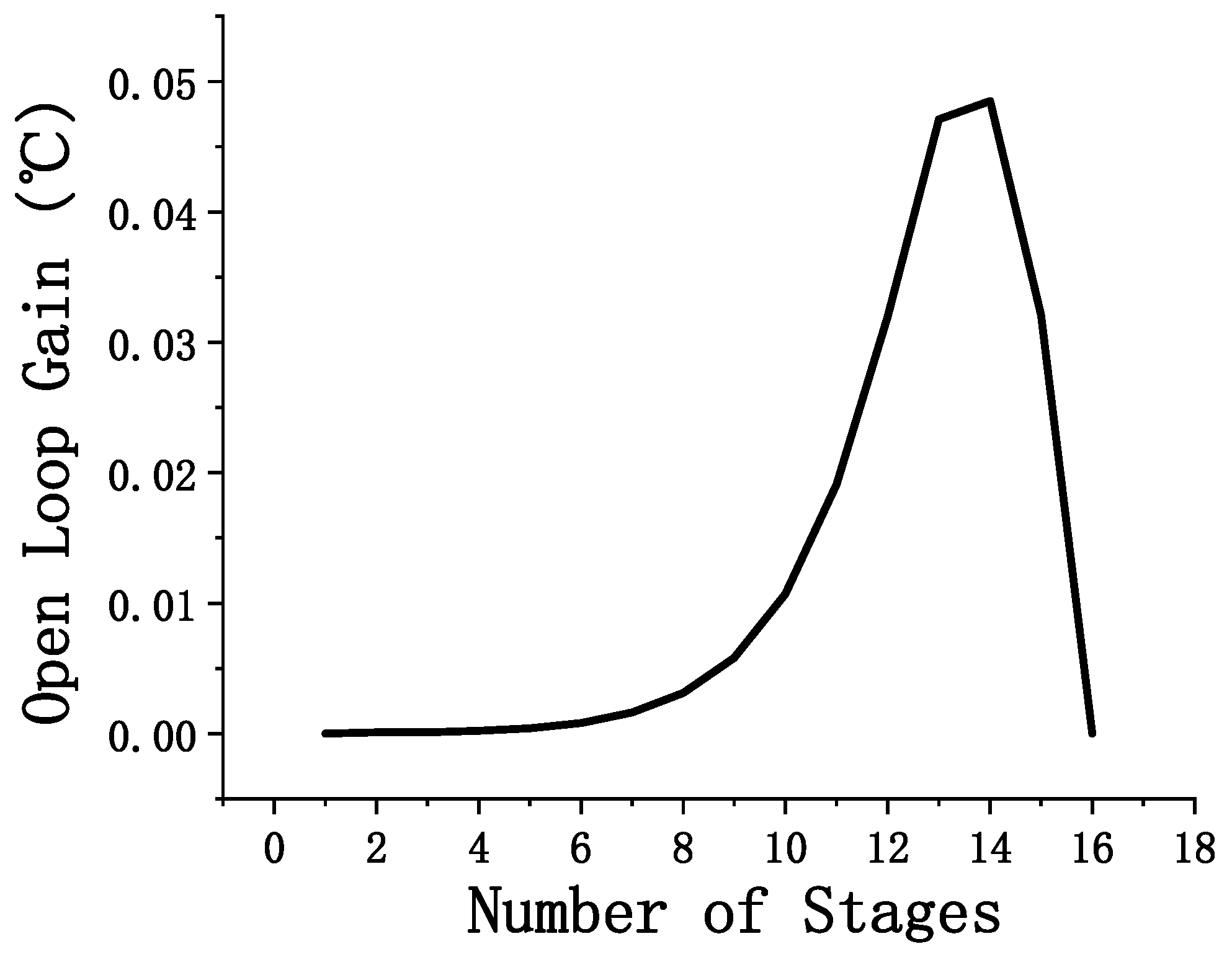

3.1. Effect of the Number of Theoretical Stages

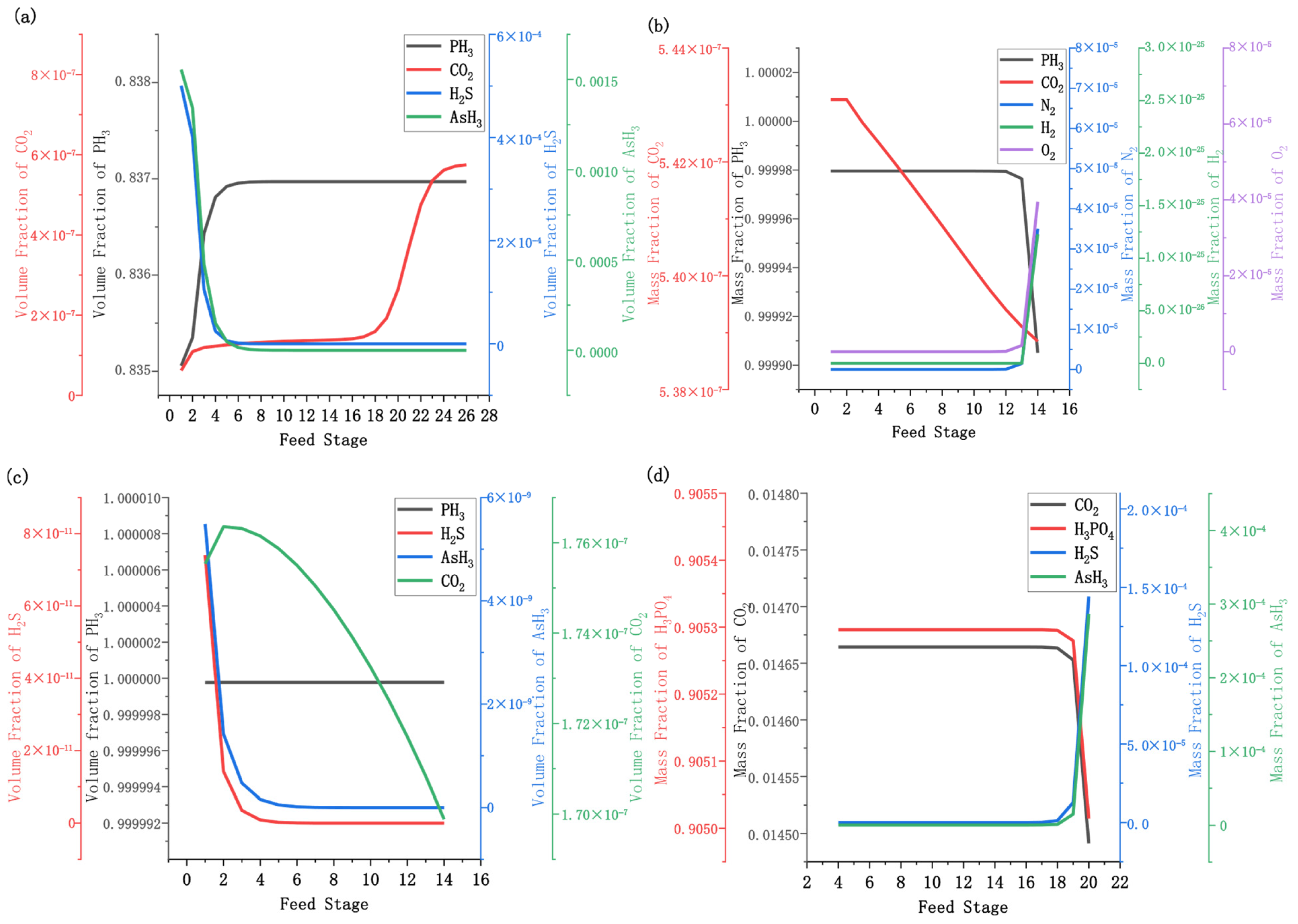

3.2. Effect of Feed Stage

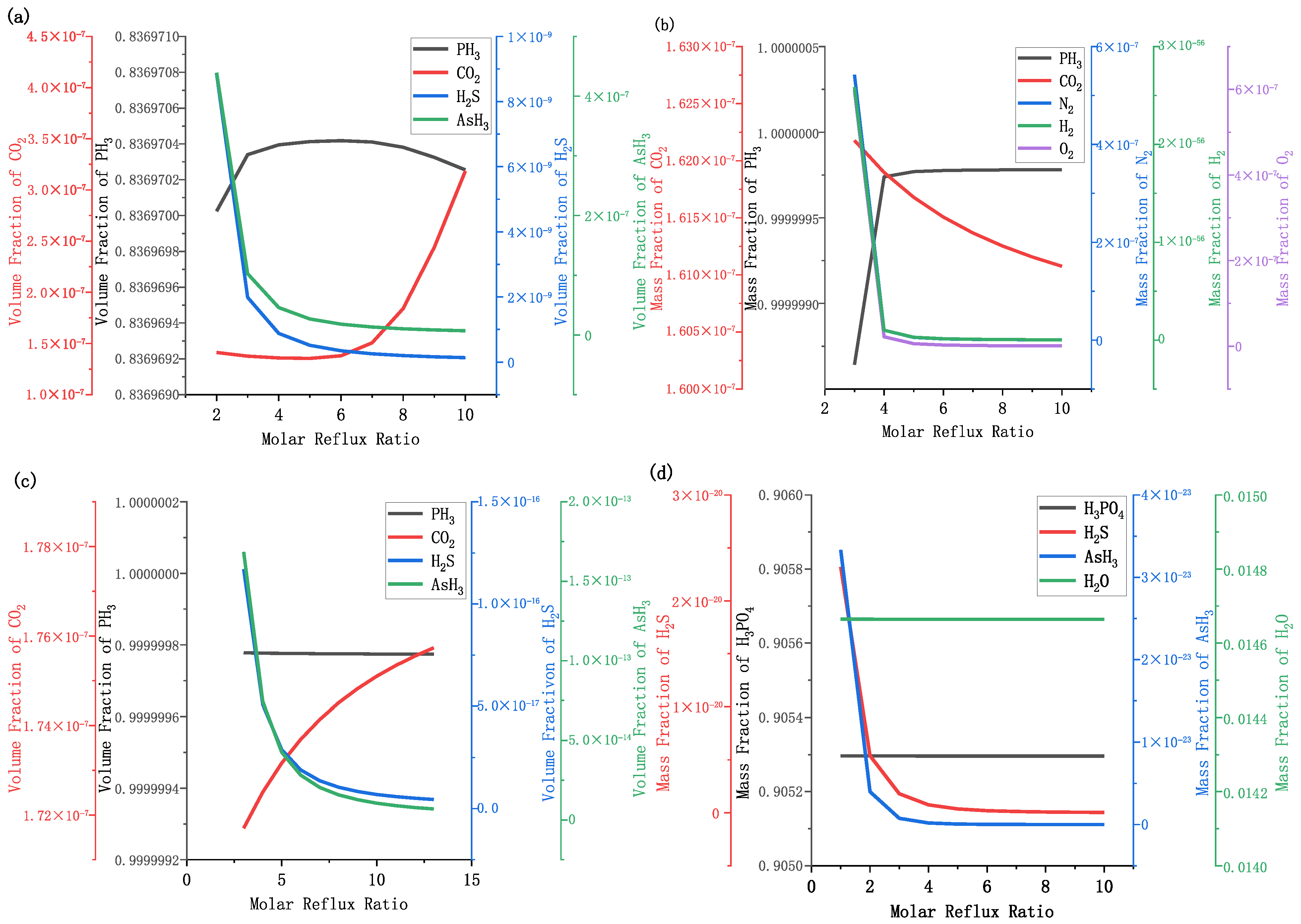

3.3. Effect of Molar Reflux Ratio

4. Simulation Results and Optimization

4.1. Simulation Results

4.2. Process Optimization

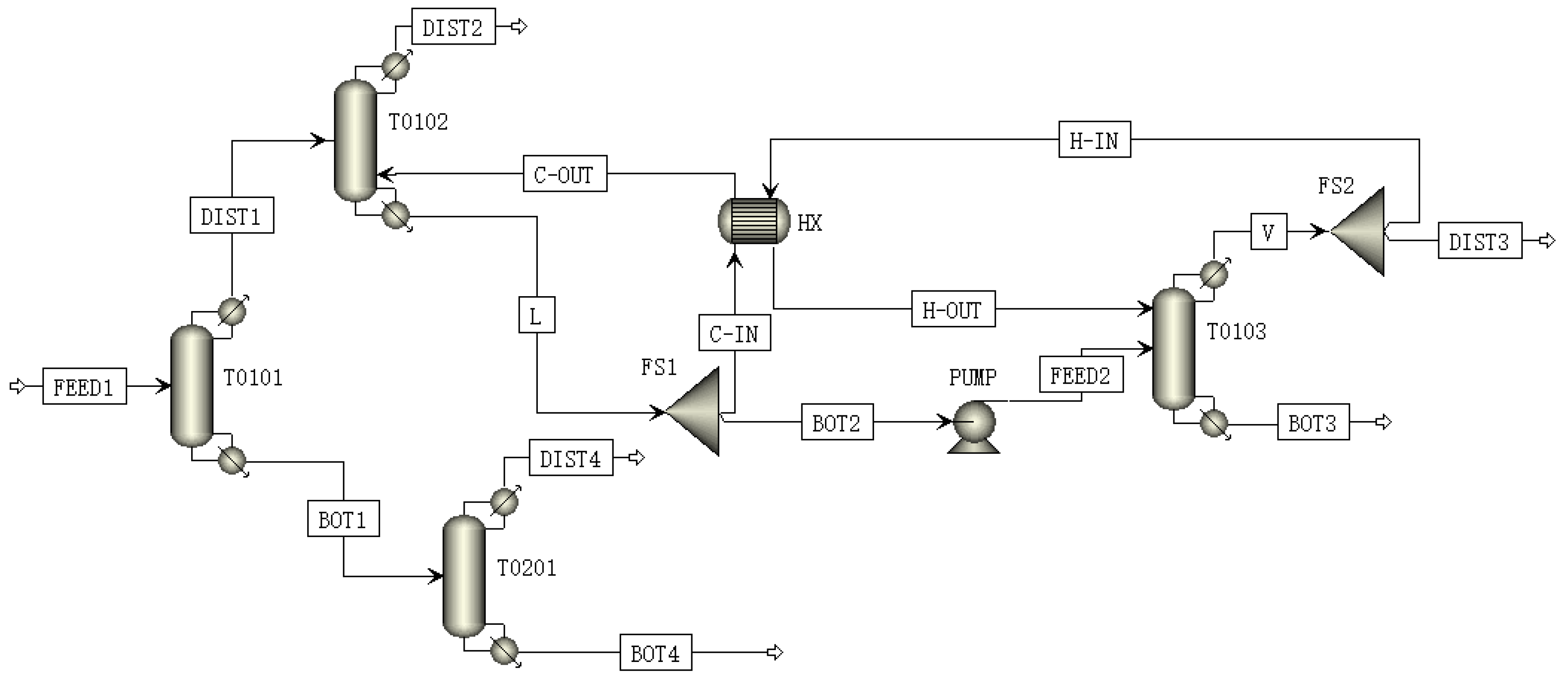

4.2.1. Four-Column Refining Process

4.2.2. Double-Effect Distillation

5. Dynamic Simulation Analysis

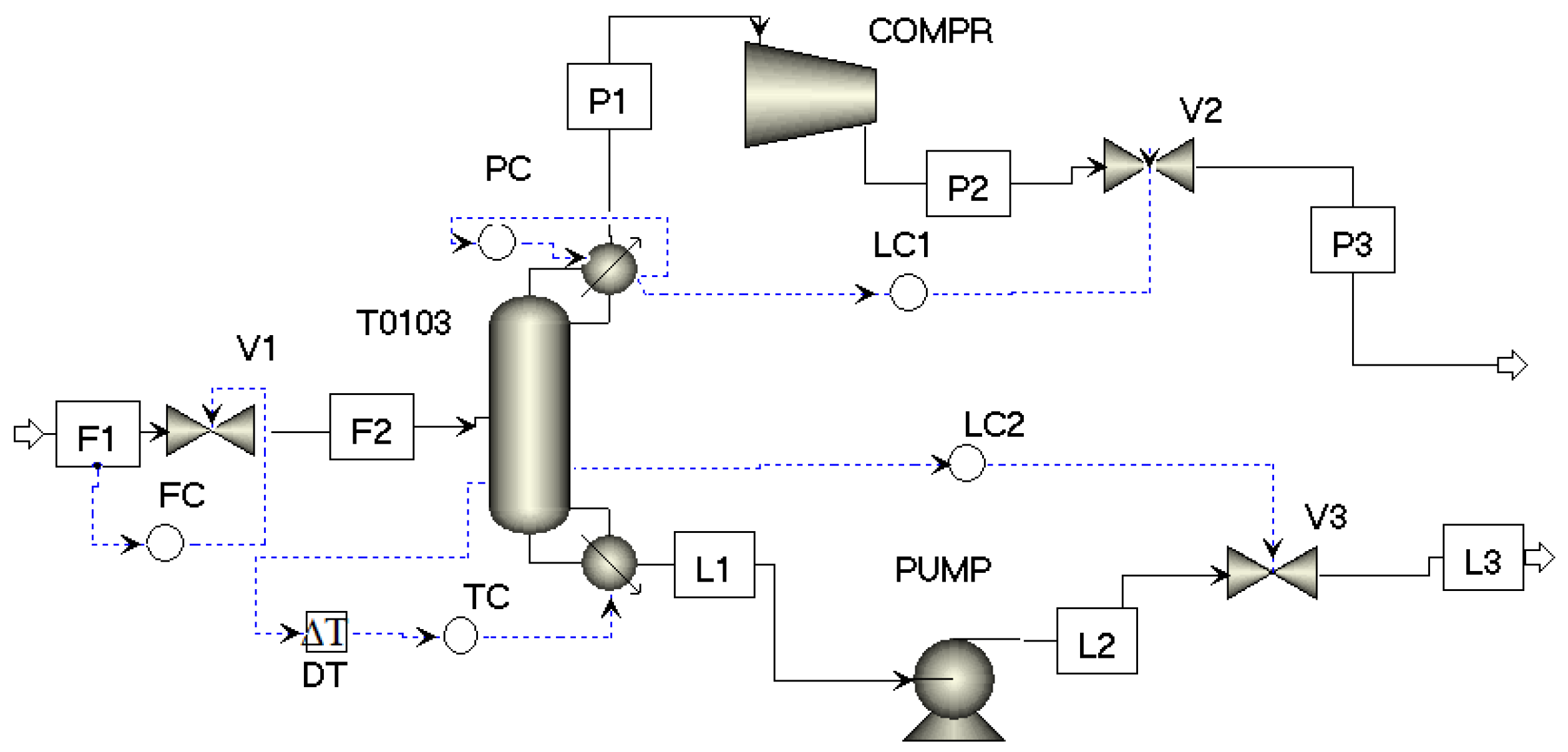

5.1. Dynamic Simulation Parameter Design

5.2. Selection of Control Schemes

5.3. Selection of Temperature-Sensitive Stage and Controller Parameter Tuning

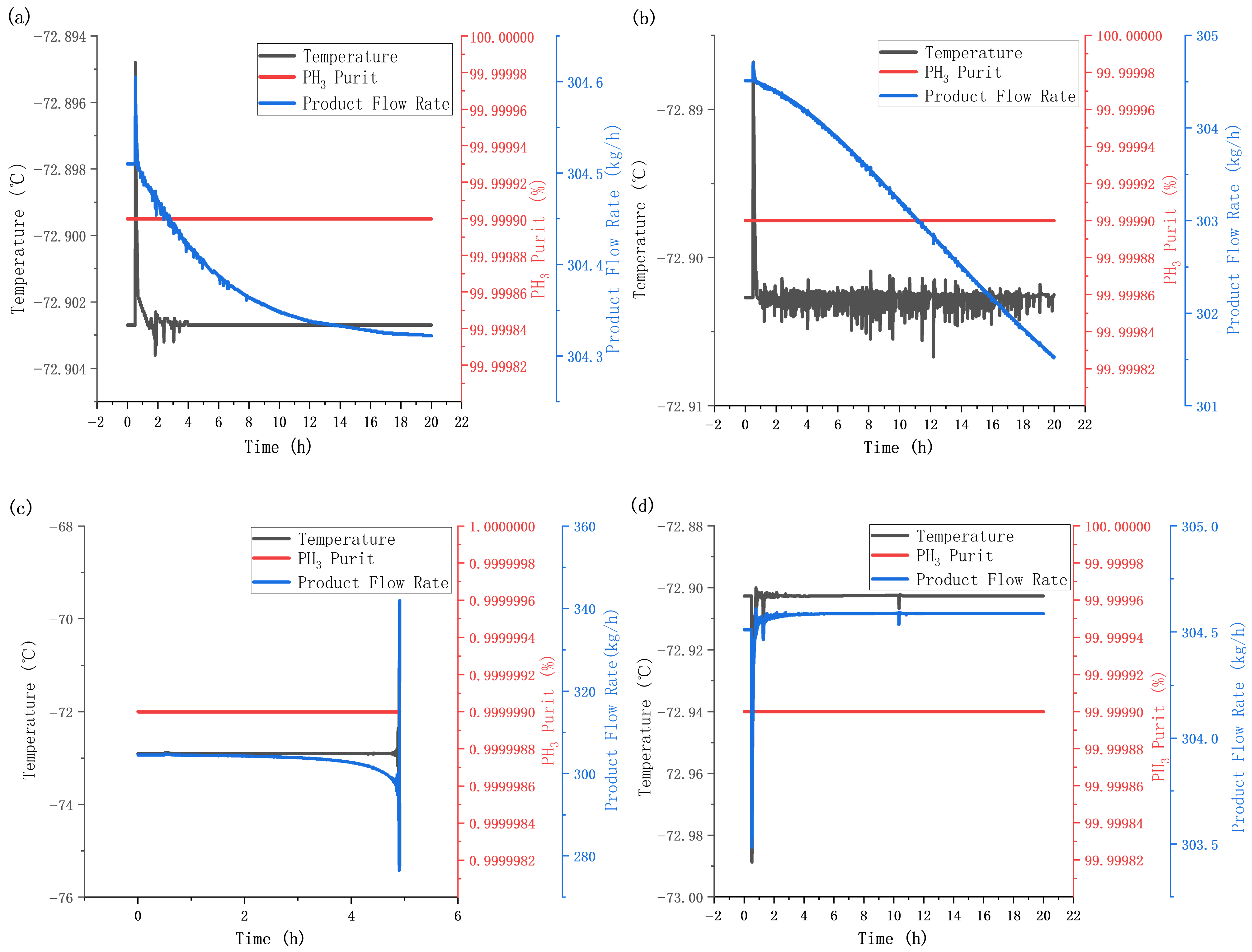

5.4. Disturbance Testing

5.4.1. Feed Flow Rate Disturbance Test

5.4.2. Feed Composition Disturbance Test

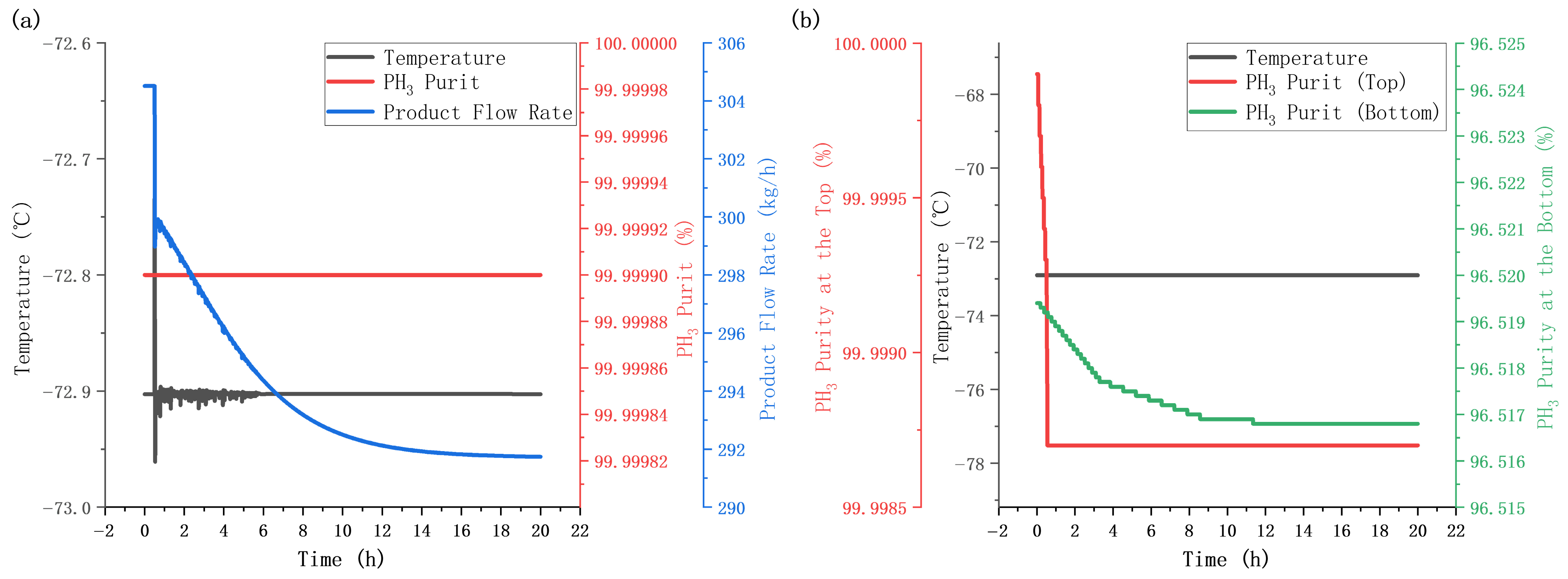

5.4.3. Steady-State Simulation After Disturbance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gui, J.; Ji, M.W.; Liu, J.J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.T.; Zhu, H.S. Phosphine-Initiated Cation Exchange for Precisely Tailoring Composition and Properties of Semiconductor Nanostructures: Old Concept, New Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3683–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.P.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, R.G.; Li, L.; Xu, X.W.; Li, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zheng, S.Z.; et al. Boosting performance and stability of inverted perovskite solar cells by modulating the cathode interface with phenyl phosphine-inlaid semiconducting polymer. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Lee, H.H. Phosphine Electrochemical Sensor Using Gold-Deposited Polytetrafluoroethylene Membrane. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 5654–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershcovitch, A.; Gushenets, V.I.; Seleznev, D.N.; Bugaev, A.S.; Dugin, S.; Oks, E.M.; Kulevoy, T.V.; Alexeyenko, O.; Kozlov, A.; Kropachev, G.N.; et al. Molecular ion sources for low energy semiconductor ion implantation (invited). Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 02B702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Lv, Y.F.; Zhao, S.C. Chemical Vapor Deposition and Thermal Oxidation of Cuprous Phosphide Nanofilm. Coatings 2022, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Gao, Z.G.; Cheng, J.C.; Gong, J.B.; Wang, J.K. Research progress on preparation and purification of fluorine-containing chemicals in lithium-ion batteries. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 41, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.J. A System for Preparing Phosphine and Its Preparation Method. CN114620695B, 7 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Shi, C.J.; Xu, X. A Method for Preparing Phosphine. CN103253640A, 21 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, E.J.; Ridgway, F.A. Production of Phosphine. US3371994, 5 March 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.F.; Gong, S.J.; Chen, J.B. Phosphine Synthesis and Purification Methods. CN111892030A, 6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, G.M.; McManus, J.V. Process and Composition for Purifying Semiconductor Process Gases to Remove Lewis Acid and Oxidant Impurities Therefrom. DE69427357, 31 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bouard, P.; Labrune, P.; Villermet, A.; Gastiger, M. Process for the Separation of a Gaseous Hydride or a Mixture of Gaseous Hydrides with the Aid of a Membrane. FR2710044, 24 March 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.L. Low-Temperature, Low-Pressure Capture Device for Phosphine and Its Preparation Process. CN1384107, 11 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.J.; Xu, Q.Y. A Method and Apparatus for Efficiently Purifying Electronic-Grade Phosphine by Azeotropic Distillation. CN120502120A, 19 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.S.; Xia, Z.Y.; Yang, Z.; Heng, Z.B.; Ye, R.; Liu, Y.; Wan, F.Q.; Cai, J.X.; Tian, K.; Lu, S. An Electronic-Grade Phosphine Purification System and Method. CN117339340A, 5 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Zeng, X.Y. A Method and Apparatus for the Synthesis and Purification of Electronic-Grade Phosphine. CN111453708A, 28 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.Z.; Luo, Y.Z.; Zhou, P.F.; Zhang, X.L. The Simulation and Optimization of the Tetrafluoroethylene Rectification Process. Separations 2024, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; ten Kate, A.; Mooijer, M.; Delgado, J.; Fosbol, P.L.; Thomsen, K. Comparison of Activity Coefficient Models for Electrolyte Systems. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 1334–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.I.; Boyack, J.R. Density, Electrical Conductivity, and Vapor Pressure of Concentrated Phosphoric Acid. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1969, 14, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierlein, J.A.; Kay, W.B. Phase Equilibrium Properties of System Carbon Dioxide-Hydrogen Sulfide sulfide. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1953, 45, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 2091-2008; Phosphoric Acid for Industrial Use. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 28159-2011; Electronic Grade Phosphoric Acid. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Zhang, J.T.; Liang, S.R.; Feng, X.A. A novel multi-effect methanol distillation process. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2010, 49, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zeng, X.Y. A Synthesis and Purification Apparatus for Electronic-Grade Phosphine. CN212982473U, 16 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Luyben, W.L. Design and Control of a Methanol Reactor/Column Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 6150–6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, C.A.T.; Zúñiga, R.P.; García, M.M.; Cabral, S.R.; Calixto-Rodriguez, M.; Martínez, J.S.V.; Enriquez, M.G.M.; Estrada, A.J.P.; Torres, G.O.; Vázquez, F.D.S.; et al. Design and Control Applied to an Extractive Distillation Column with Salt for the Production of Bioethanol. Processes 2022, 10, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, P.L.; Hu, C.; Luo, J.H.; Wen, M.; Yu, B.; Jiang, F.; An, Y.T.; Shi, Y.; Song, J.F.; et al. Dynamic simulation of a cryogenic batch distillation process for hydrogen isotopes separation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 11955–11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Mole Flow Rate (kmol/h) | Mole Fraction (%) | Mass Flow Rate (kg/h) | Mass Fraction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 20 | 38.55 | 619.48 | 50.96 |

| H2O | 28 | 53.97 | 504.43 | 41.49 |

| H3PO4 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 3.92 | 0.32 |

| N2 | 1.2 | 2.31 | 33.62 | 2.77 |

| H2 | 1.2 | 2.31 | 2.42 | 0.20 |

| H2S | 0.12 | 0.23 | 4.09 | 0.34 |

| O2 | 1.2 | 2.31 | 38.40 | 3.16 |

| AsH3 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 9.35 | 0.77 |

| CO2 | 6 × 10−6 | - | 2.64 × 10−4 | - |

| Component | Mole Flow Rate (kmol/h) | Mole Fraction (%) | Mass Flow Rate (kg/h) | Mass Fraction (%) | Normal Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH3 | 11.25 | 45.22 | 382.47 | 31.46 | −87.69 |

| H2O | 1 | 4.02 | 18.02 | 1.48 | 100.01 |

| H3PO4 | 6.79 | 27.29 | 665.39 | 54.73 | Decomposes |

| P | 2 | 8.04 | 61.95 | 5.10 | Sublimes |

| CO2 | 6 × 10−6 | - | 2.64 × 10−4 | - | Sublimes |

| N2 | 1.2 | 4.82 | 33.62 | 2.77 | −195.75 |

| H2 | 1.2 | 4.82 | 2.42 | 0.20 | −252.76 |

| H2S | 0.12 | 0.48 | 4.09 | 0.34 | −60.32 |

| O2 | 1.2 | 4.82 | 38.40 | 3.16 | −182.96 |

| ASH3 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 9.35 | 0.77 | −62.40 |

| Verification Systems | Validation Variables | Data Source | Number of Data Points | Average Relative Deviation | Maximum Relative Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O-H3PO4 | Pressure | from [19] | 10 | 2.6% | 5.5% |

| H2S-CO2 | Temperature | from [20] | 14 | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| Model | Theoretical Stages Number | Molar Reflux Ratio | Feed Stage | Molar Distillate Feed Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0101 | 28 | 4 | 6 | 0.6 |

| T0102 | 14 | 6 | 11 | 0.25 |

| T0103 | 16 | 4 | 14 | 0.8 |

| T0201 | 20 | 8 | 15 | 0.02 |

| T0202 | 20 | 4 | 15 | 0.2 |

| Matter | DIST1 (kg/h) | BOT1 (kg/h) | BOT2 (kg/h) | DIST3 (kg/h) | BOT4 (kg/h) | BOT5 (kg/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH3 | 382.5 | 6.0 × 10−9 | 378.0 | 304.5 | 1.9 × 10−14 | 0 |

| H2O | 2 × 10−26 | 18.0 | 0 | 0 | 17.3 | 7.2 × 10−10 |

| H3PO4 | 3 × 10−82 | 665.4 | 0 | 0 | 665.4 | 665.4 |

| P | 5 × 10−47 | 61.9 | 0 | 0 | 61.9 | 31.4 |

| CO2 | 2.6 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−13 | 2.6 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−4 | 0 | 0 |

| N2 | 33.6 | 2.6 × 10−39 | 1.1 × 10−6 | 1.1 × 10−6 | 0 | 0 |

| H2 | 2.4 | 2.3 × 10−221 | 6.3 × 10−56 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H2S | 1.6 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 × 10−9 | 1.1 × 10−4 | 1.7 × 10−16 |

| O2 | 38.4 | 1.0 × 10−34 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 1.2 × 10−6 | 0 | 0 |

| AsH3 | 2.3 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 × 10−7 | 6.5 × 10−5 | 5.7 × 10−17 |

| Model | Condenser Heat Duty (kW) | Reboiler Heat Duty (kW) |

|---|---|---|

| T0101 | −273.5 | 255.4 |

| T0102 | −107.3 | 60.0 |

| T0103 | −143.8 | 179.8 |

| T0201 | −18.8 | 19.3 |

| T0202 | −107.6 | 227.2 |

| Model | Condenser Heat Duty (kW) | Reboiler Heat Duty (kW) |

|---|---|---|

| T0101 | −273.5 | 255.4 |

| T0102 | −107.4 | 0 |

| T0103 | 0 | 97.6 |

| T0201 | −18.8 | 19.3 |

| Comparison | Before Adopting Double-Effect Distillation | After Adopting Double-Effect Distillation |

|---|---|---|

| Total heat duty (kW) | 1057.9 | 771.9 |

| Flow rate of phosphine products (kg/h) | 304.5 | 304.5 |

| Purity of phosphine products (%) | 99.999943 | 99.999936 |

| Flow rate of phosphoric acid products (kg/h) | 744.7 | 744.7 |

| Purity of phosphoric acid products (%) | 89.4 | 89.4 |

| Controller | Controller Action | Gain | Integral Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow rate controller FC | Reverse | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Pressure controller PC | Direct | 10 | 60 |

| Liquid level controller LC1 | Direct | 2 | 9999 |

| Liquid level controller LC2 | Direct | 2 | 9999 |

| Temperature controller TC | Reverse | 21.2 | 4.0 |

| Disturbance | Purity of Phosphine Products (%) |

|---|---|

| Undisturbed | 99.999936 |

| Feed flow rate reduced by 10% | 99.999937 |

| Feed flow rate increased by 100% | 99.999924 |

| PH3 content reduced by 1% | 99.999929 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Du, Y.; Tang, X. Design, Simulation, and Parametric Analysis of an Ultra-High Purity Phosphine Purification Process with Dynamic Control. Separations 2025, 12, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12110309

Wang J, Guo J, Liu Y, Zhou S, Du Y, Tang X. Design, Simulation, and Parametric Analysis of an Ultra-High Purity Phosphine Purification Process with Dynamic Control. Separations. 2025; 12(11):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12110309

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jingang, Jinyu Guo, Yu Liu, Shuyue Zhou, Yawei Du, and Xuejiao Tang. 2025. "Design, Simulation, and Parametric Analysis of an Ultra-High Purity Phosphine Purification Process with Dynamic Control" Separations 12, no. 11: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12110309

APA StyleWang, J., Guo, J., Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Du, Y., & Tang, X. (2025). Design, Simulation, and Parametric Analysis of an Ultra-High Purity Phosphine Purification Process with Dynamic Control. Separations, 12(11), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12110309