Fostering Teachers’ Work Engagement: The Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy Toward One’s Own Emotions, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Job Resources

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement

1.2. The Role of Job Resources

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teachers’ Professional Self-Efficacy

2.2.2. Teachers’ Emotional Self-Efficacy Concerning Their Own Emotions

2.2.3. Job Resources

2.2.4. Work Engagement

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2013). Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burić, I., Zuffianò, A., & López-Pérez, B. (2022). Longitudinal relationship between teacher self-efficacy and work engagement: Testing the random-intercept cross-lagged panel model. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 70, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V. (Ed.). (2001). La valutazione dell’autoefficacia. Costrutti e strumenti. Erickson. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, E., Baroncelli, A., & Toselli, M. (2015). Meta-emotion philosophy in early childhood teachers: Psychometric properties of the Crèche Educator Emotional Styles Questionnaire. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacre Pool, L., & Qualter, P. (2013). Emotional self-efficacy, graduate employability, and career satisfaction: Testing the associations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., Gutiérrez-Cobo, M. J., Rodriguez-Corrales, J., & Cabello, R. (2017). Teachers’ affective well-being and teaching experience: The protective role of perceived emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilar-Corbi, R., Perez-Soto, N., Izquierdo, A., Castejón, J.-L., & Pozo-Rico, T. (2024). Emotional factors and self-efficacy in the psychological well-being of trainee teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1434250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B. A., Schutte, N. S., & Hine, D. W. (2008). Development and preliminary validation of an emotional self-efficacy scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, M., Razmus, W., & Żaliński, A. (2017). Dynamic relationships between personal resources and work engagement in entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippke, S. (2020). Self-Efficacy. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 4713–4719). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagulova, A. (2021). Predictors of work engagement: Drawing on job demands-resources theory and public service motivation. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 80, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisanti, R., Paplomatas, A., & Bertini, M. (2008). Misurare le dimensioni positive nel lavoro in sanità: Un contributo all’adattamento italiano dell’UWES—Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia, 30, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Qualter, P., Gardner, K. J., Pope, D., Hutchinson, J. M., & Whiteley, H. E. (2012). Ability emotional intelligence, trait emotional intelligence, and academic success in British secondary schools: A5-year longitudinal study. Learning and Individual Differences, 22, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelhorn, I., Lindl, A., & Kuhbandner, C. (2023). Evaluating a training of emotional competence for pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A. (2021). A dual path model of work-related well-being in healthcare and social work settings: The interweaving between trait emotional intelligence, end-user job demands, coworkers related job resources, burnout, and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 660035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesi, A., & Aiello, A. (2021). The assessment of organizational well-being: The “Integrated tool of organizational well-being (SIVBO)” into the framework of the “Job Demands-Resources” model. Psicologia della Salute, 2, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A., Baroncelli, A., Ciucci, E., Facci, C., & Aiello, A. (2024). Trait authenticity as an “enzyme” for personal resources and work engagement: A study among teachers within the framework of the job demands-resources model. European Review of Applied Psychology, 74(5), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., & Fischbach, A. (2013). Work engagement among employees facing emotional demands. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 12, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Years of professional experience | 17.11 | 10.95 | 0.43 | −0.76 | − | ||||

| 2—Work engagement | 4.86 | 0.75 | −1.32 | 2.43 | −0.03 | − | |||

| 3—Professional self-efficacy | 3.64 | 0.55 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.09 * | 0.41 ** | − | ||

| 4—Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions | 3.78 | 0.52 | −0.15 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.40 ** | 0.48 ** | ||

| 5—Job resources | 3.82 | 1.14 | −0.38 | −0.23 | −0.06 | 0.41 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.29 ** | - |

| Work Engagement | |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | F(3,588) = 56.278 **; R2 = 0.22 |

| Years of professional experience | −0.07 |

| Professional self-efficacy | 0.29 ** |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions | 0.26 ** |

| Step 2 | F(7,588) = 40.313 **; ΔR2 = 0.10, R2 = 0.32 |

| Years of professional experience | −0.04 |

| Professional self-efficacy | 0.28 ** |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions | 0.19 ** |

| Job resources | 0.29 ** |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions × Professional self-efficacy | −0.14 ** |

| Professional self-efficacy x Job resources | −0.04 |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions × Job resources | −0.02 |

| Step 3 | F(8,588) = 36.359 **; ΔR2 = 0.01 *, R2 = 0.33 |

| Years of professional experience | −0.05 |

| Professional self-efficacy | 0.26 ** |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions | 0.17 ** |

| Job resources | 0.26 ** |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions × Professional self-efficacy | −0.15 ** |

| Professional self-efficacy x Job resources | −0.06 |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions × Job resources | −0.02 |

| Emotional self-efficacy toward one’s own emotions × Professional self-efficacy × Job resources | 0.11 * |

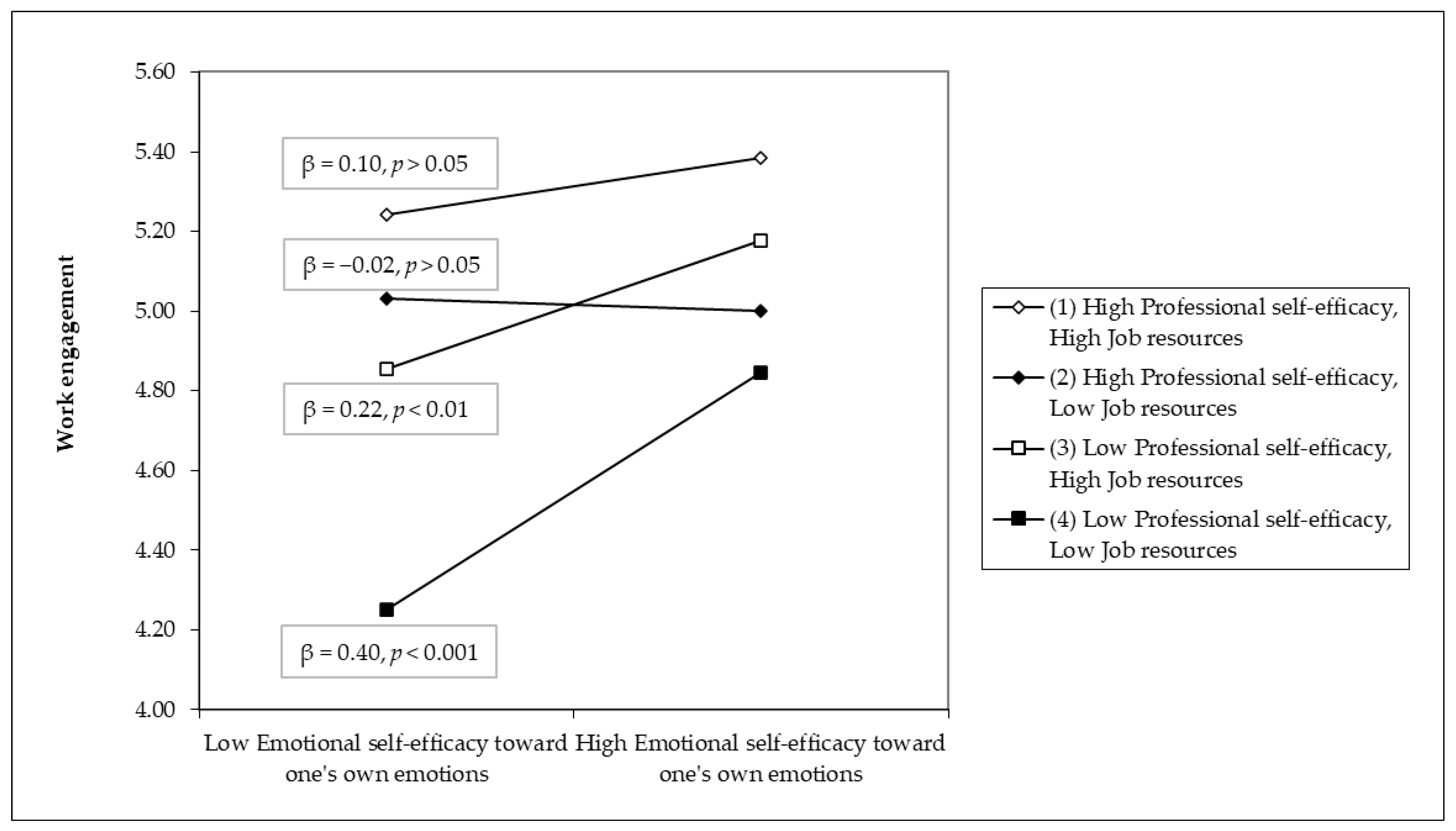

| Pair of Slopes | Slope Difference | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) and (2) | 0.17 | 1.229 | 0.220 |

| (1) and (3) | −0.17 | −1.492 | 0.136 |

| (1) and (4) | −0.44 | −3.744 | <0.001 |

| (2) and (3) | −0.34 | −2.201 | 0.028 |

| (2) and (4) | −0.61 | −4.414 | <0.001 |

| (3) and (4) | −0.27 | −1.992 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tesi, A.; Baroncelli, A.; Facci, C.; Aiello, A.; Ciucci, E. Fostering Teachers’ Work Engagement: The Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy Toward One’s Own Emotions, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Job Resources. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090176

Tesi A, Baroncelli A, Facci C, Aiello A, Ciucci E. Fostering Teachers’ Work Engagement: The Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy Toward One’s Own Emotions, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Job Resources. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090176

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesi, Alessio, Andrea Baroncelli, Carolina Facci, Antonio Aiello, and Enrica Ciucci. 2025. "Fostering Teachers’ Work Engagement: The Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy Toward One’s Own Emotions, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Job Resources" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090176

APA StyleTesi, A., Baroncelli, A., Facci, C., Aiello, A., & Ciucci, E. (2025). Fostering Teachers’ Work Engagement: The Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy Toward One’s Own Emotions, Professional Self-Efficacy, and Job Resources. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090176