Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Time Perspective Between Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Cannabis Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescents

1.2. Time Perspective Theory

1.3. Time Perspective Theory Applied to Post-Traumatic Stress

1.4. Associations Between Post-Traumatic Stress, Time Perspective and Cannabis Use

1.5. Aim of This Study and Hypotheses

- Adolescents with PTSS show an imbalanced TP characterized by high orientations towards Past Negative and Present Fatalistic and low orientation towards Past Positive and Future.

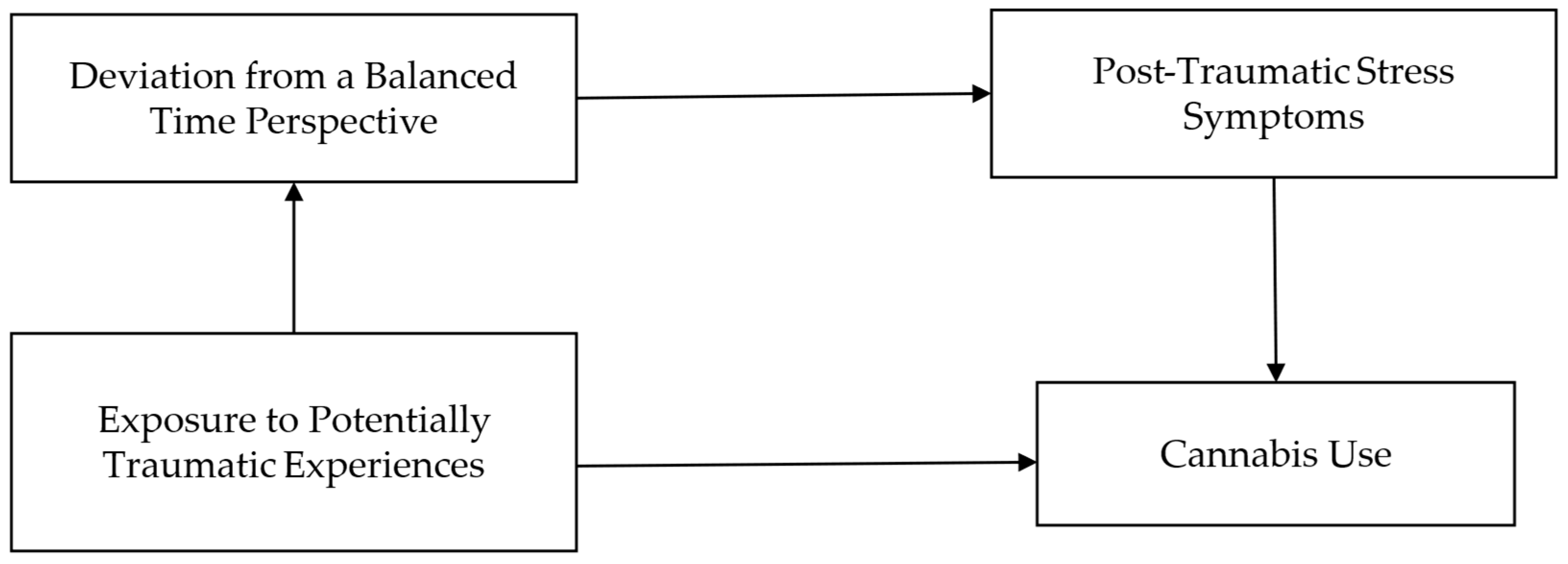

- The relationship between EPTE and PTSS is mediated by DBTP analogous to the model proposed by Tomich et al. (2022) (see Figure 1).

- The relationship between EPTE and cannabis use is mediated by PTSS and DBTP serially (see Figure 2).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen–2

2.2.2. Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory and Deviation from a Balanced Time Perspective

2.2.3. Cannabis Use

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms, Deviation from Balanced Time Perspective and Cannabis Use

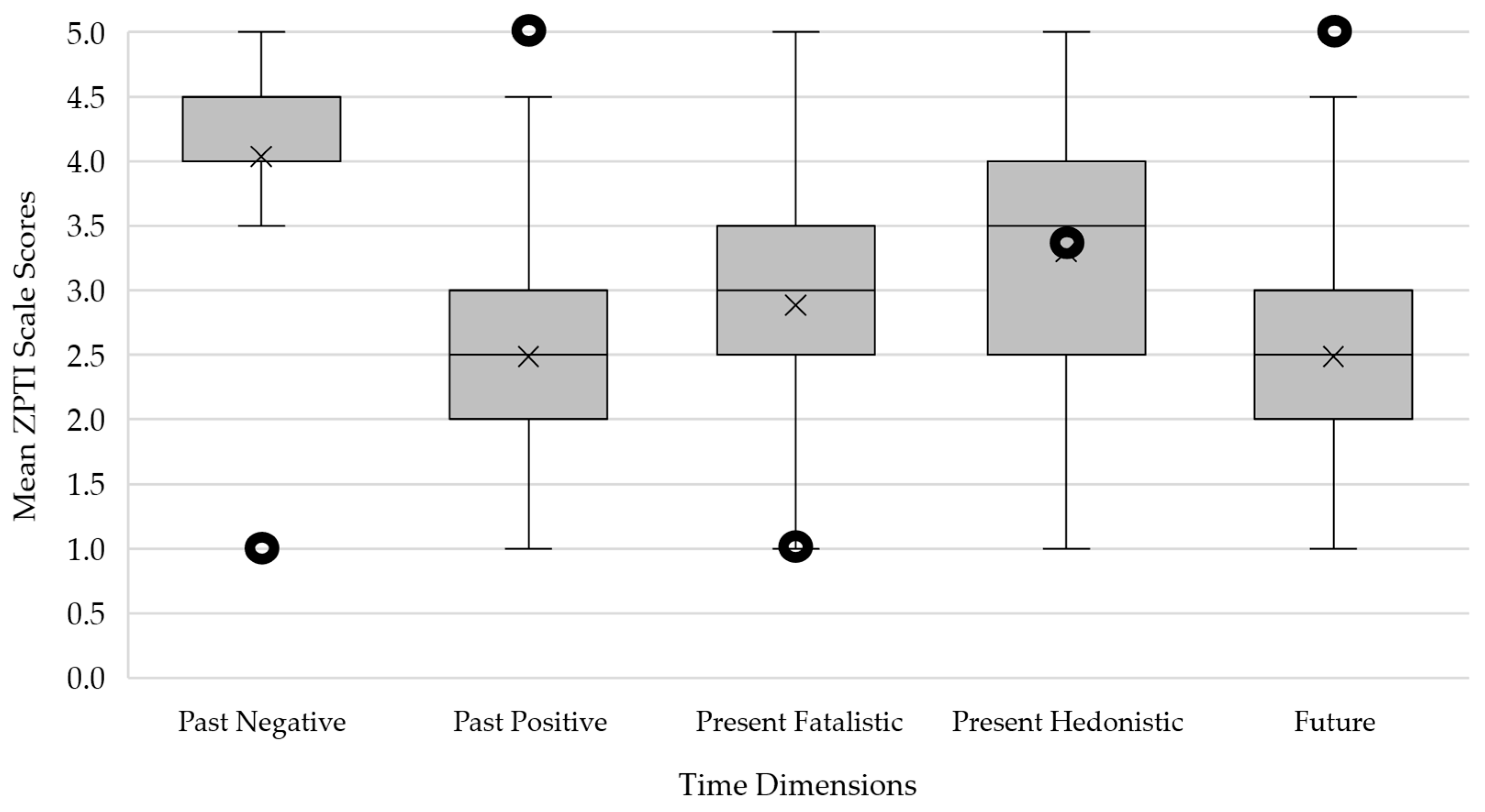

3.3. Time Perspective Profile

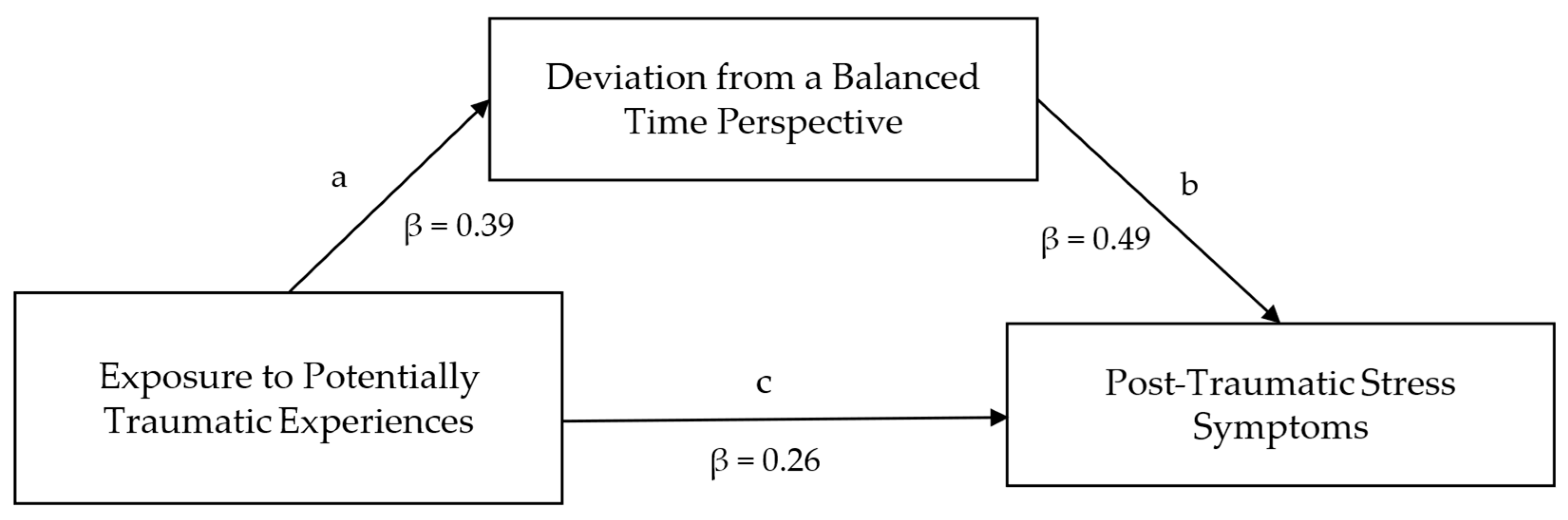

3.4. Mediation Analysis 1: Exposure to Potentially Traumatic Experiences, Deviation from a Balanced Time Perspective and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms

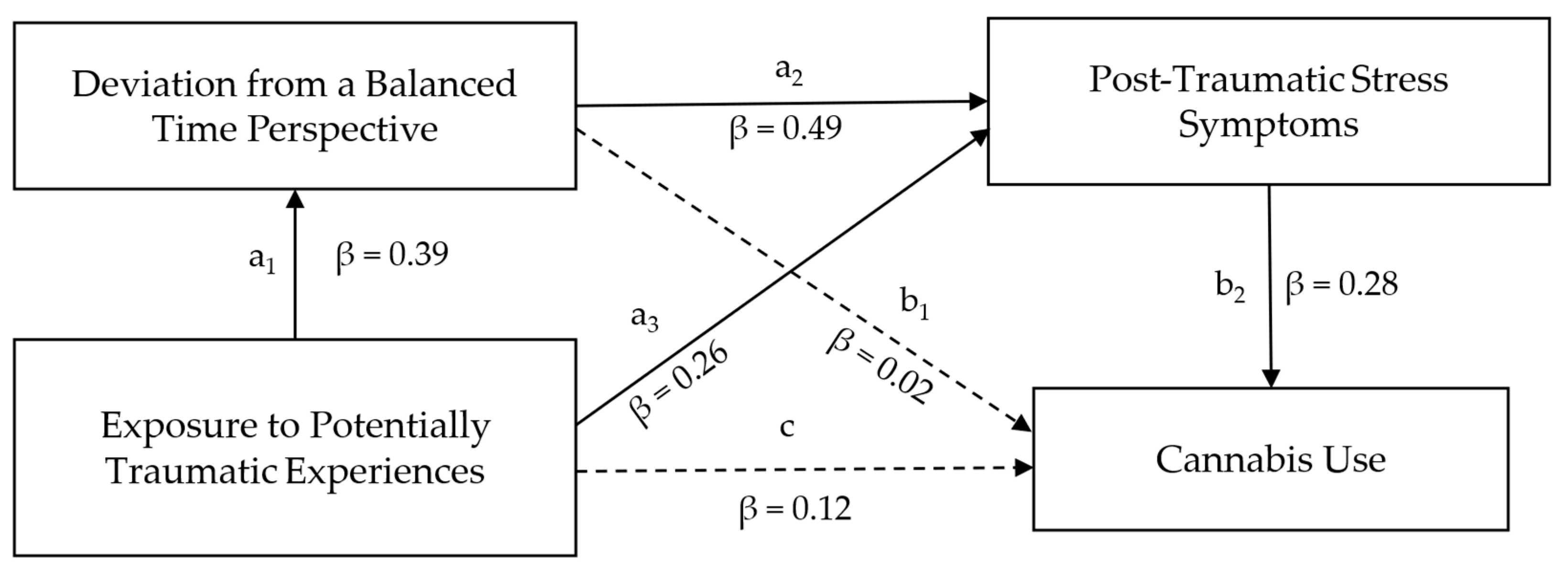

3.5. Mediation Analysis 2: Exposure to Potentially Traumatic Experiences, Deviation from a Balanced Time Perspective, Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms and Cannabis Use

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTSSs | Post-traumatic stress symptoms |

| TP | Time perspective |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| EPTEs | Exposure to potentially traumatic experiences |

| DBTP | Deviation from a Balanced Time Perspective |

| DBT-r | Deviation from a Balanced Time Perspective-revised version |

| CATS-2 | Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen-2 |

| ZTPI | Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory |

References

- Aguilar-Raab, C., Heene, M., Grevenstein, D., & Weinhold, J. (2015). Assessing drug consumption behavior with the Heidelberger Drogenbogen (Heidelberg drug scales): Reliabilities, validities, and cut-off criteria. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(13), 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidis, T., Fieulaine, N., Simonin, L., & Rolland, G. (2006). Cannabis use, time perspective and risk perception: Evidence of a moderating effect. Psychology and Health, 21(5), 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilola, O., Stevanovic, D., Moreira, P., Dodig-Ćurković, K., Franic, T., Djoric, A., Davidovic, N., Avicenna, M., Noor, I. M., Monteiro, A. L., Ribas, A., Stupar, D., Deljkovic, A., Nussbaum, L., Thabet, A., Ubalde, D., Petrov, P., Vostanis, P., & Knez, R. (2021). External locus-of-control partially mediates the association between cumulative trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms among adolescents from diverse background. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(6), 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E., Spruijt-Metz, D., Unger, J. B., Rohrbach, L. A., Sun, P., & Sussman, S. (2013). Bidirectional associations between future time perspective and substance use among continuation high-school students. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(8), 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Valencia, M., Calderón-Delgado, L., Trejos-Castillo, E., & O’Boyle, M. (2017). Cognitive profiles of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 17(3), 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basedow, L. A., Kuitunen-Paul, S., Roessner, V., & Golub, Y. (2020). Traumatic events and substance use disorders in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 523621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, M. R., Bottlender, R., Rösler, M., & Stieglitz, R.-D. (2018). The AMDP system: Manual for assessment and documentation of psychopathology in psychiatry (M. R. Broome, R. Bottlender, M. Rösler, & R.-D. Stieglitz, Eds.; 9th ed.). Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cisler, J. M., & Herringa, R. J. (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the developing adolescent brain. Biological Psychiatry, 89(2), 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, A., Felton, J. W., MacPherson, L., & Lejuez, C. W. (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of sensation seeking, risk taking propensity, and impulsivity across early to middle adolescence. Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, J. R., Kirisci, L., Reynolds, M., Clark, D. B., Hayes, J., & Tarter, R. (2010). PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, D., Treiber, L., & Bosnjak, M. (2019). Development and psychometric evaluation of a short version of the time perspective inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(2), 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A. G., Burgers, D. E., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Bundestag. (2024, February 23). Nach langem Ringen: Bundestag verabschiedet Cannabis-Legalisierung [After a long struggle: Bundestag passes cannabis legalization]. Available online: https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2024/kw08-de-cannabis-990684 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Donbaek, D. F., Elklit, A., & Pedersen, M. U. (2014). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptom clusters predicting substance abuse in adolescents. Mental Health and Substance Use, 7(4), 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., & Michael, T. (2004). Intrusive re-experiencing in post-traumatic stress disorder: Phenomenology, theory, and therapy. Memory, 12(4), 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, O. L. M., Heinrichs, N., Wagner, B., & van Noort, B. M. (2025). Poly-victimization and post-traumatic stress symptoms in care experienced youth: The mediating role of mentalizing. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 16(1), 526301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction. (2024). European drug report 2024: Trends and developments. European Union Drugs Agency. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C. J. (2016). An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. In Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (4th ed.). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finan, L. J., Linden-Carmichael, A. N., Adams, A. R., Youngquist, A., Lipperman-Kreda, S., & Mello, Z. R. (2021). Time perspective and substance use: An examination across three adolescent samples. Addiction Research & Theory, 30(2), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombouchet, Y., Pineau, S., Perchec, C., Lucenet, J., & Lannegrand, L. (2023). The development of emotion regulation in adolescence: What do we know and where to go next? Social Development, 32(4), 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A., Oyanadel, C., Zimbardo, P., González-Loyola, M., Olivera-Figueroa, L. A., & Peñate, W. (2022). Mindfulness and balanced time perspective: Predictive model of psychological well-being and gender differences in college students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12(3), 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, K. P., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2011). Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, M., Kelleher, I., Clarke, M., Lynch, F., Arseneault, L., Connor, D., Fitzpatrick, C., & Cannon, M. (2010). Cannabis use and childhood trauma interact additively to increase the risk of psychotic symptoms in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 40(10), 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heradstveit, O., Skogen, J. C., Hetland, J., Stewart, R., & Hysing, M. (2019). Psychiatric diagnoses differ considerably in their associations with alcohol/drug-related problems among adolescents. A Norwegian population-based survey linked with national patient registry data. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 431158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, T. A., Zaur, A. J., Keeley, J. W., & Amstadter, A. B. (2022). The association between recreational cannabis use and posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 240, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (1998). Getting “stuck” in the past: Temporal orientation and coping with trauma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1146–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Ramaghani, N. A., Rezaei, F., Sepahvandi, M. A., Gholamrezaei, S., & Mirderikvand, F. (2019). The mediating role of the metacognition, time perspectives and experiential avoidance on the relationship between childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1648173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, E. K., & Gullone, E. (2010). Discrepancies between adolescent, mother, and father reports of adolescent internalizing symptom levels and their association with parent symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(9), 978–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughesdon, K. A., Ford, J. D., Briggs, E. C., Seng, J. S., Miller, A. L., & Stoddard, S. A. (2021). Interpersonal trauma exposure and interpersonal problems in adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(4), 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, K. S., Zajenkowski, M., & Stolarski, M. (2020). What are the optimal levels of time perspectives? Deviation from the balanced time perspective-revisited (DBTP-r). Psychologica Belgica, 60(1), 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, A. K., & Brieske, L. T. (2025). Entwicklung des cannabiskonsums vom jugend-zum jungen erwachsenenalter sowie risiko- und schutzfaktoren für einen problematischen konsum–ergebnisse einer längsschnittstudie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz, 68, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantzian, E. J., Mack, J. E., Schatzberg, A. F., McKenna, G. J., Treece, C. J., Khantzian, N. J., Kates, W. W., Halliday, K. S., Golden, S. J., & McAuliffe, W. E. (1999). Treating addiction as a human process (reprinted 2007, 687p). Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Kleim, B., Graham, B., Fihosy, S., Stott, R., & Ehlers, A. (2013). Reduced specificity in episodic future thinking in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klicperová-Baker, M., Weissenberger, S., Poláčková šolcová, I., Děchtěrenko, F., Vňuková, M., & Ptáček, R. (2020). Development of psychological time perspective: The types, predictors, and trends. Studia Psychologica, 62(3), 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, M. A., Schnyder, U., Maier, T., Schoenbucher, V., & Mohler-Kuo, M. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents: A national survey in Switzerland. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(2), 209–216. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pbh&AN=86744981&lang=de&site=eds-live (accessed on 28 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Laureiro-Martinez, D., Trujillo, C. A., & Unda, J. (2017). Time perspective and age: A review of age associated differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layne, C. M., Greeson, J. K. P., Ostrowski, S. A., Kim, S., Reading, S., Vivrette, R. L., Briggs, E. C., Fairbank, J. A., & Pynoos, R. S. (2014). Cumulative trauma exposure and high risk behavior in adolescence: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(Suppl. S1), S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebens, M. L., & Lauth, G. W. (2016). Risk and resilience factors of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of current research. Clinical and Experimental Psychology, 2(2), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A., Clemenza, K., Rynn, M., & Lieberman, J. (2017). Evidence for the risks and consequences of adolescent cannabis exposure. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(3), 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macałka, E., Tomaszek, K., & Kossewska, J. (2022). Students’ depression and school burnout in the context of family network acceptance and deviation from balanced time perspective. Education Sciences, 12(3), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J., Klinger, S., Rosenkranz, M., & Schwarzkopf, L. (2024). Cannabis use, health problems, and criminal offences in Germany: National and state-level trends between 2009 and 2021. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 275, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G., & Stolarski, M. (2015). Emotional processes in development and dynamics of individual time perspective. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 269–286). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M. T., Andretta, J. R., Magee, J., & Worrell, F. C. (2014). What do temporal profiles tell us about adolescent alcohol use? Results from a large sample in the United Kingdom. Journal of Adolescence, 37(8), 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M. T., Worrell, F. C., Perry, J. L., Chishima, Y., Zivkovic, U., Mello, Z. R., & Cole, J. C. (2022). “Even a broken clock is right twice a day”: The case of the Zimbardo time perspective inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., Hill, E. D., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiser-Stedman, R. (2002). Towards a cognitive–behavioral model of PTSD in children and adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(4), 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, Z. R. (2019). A construct matures: Time perspective’s multidimensional, developmental, and modifiable qualities. Research in Human Development, 16(2), 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Z. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2006). The Relationship of time perspective to age, gender, and academic achievement among academically talented adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 29(3), 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Z. R., & Worrel, F. C. (2007). The adolescent and adult time inventory—English. Berkeley School of Education, The University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, Z. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2015). The past, the present, and the future: A conceptual model of time perspective in adolescence. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 115–129). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, B., & Merkel, C. (2022). Der Substanzkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Alkoholsurveys 2021 zu Alkohol, Rauchen, Cannabis und Trends [The substance use of adolescents and young adults in Germany. Results of the Alcohol Survey 2021 on alcohol, smoking, cannabis and trends]. BZgA-Forschungsbericht. [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti, M., Gooding, P. A., Triantafyllou, K., & Tarrier, N. (2015). Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(4), 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H., Tapert, S. F., Brown, S. A., Norman, S. B., & Pelham, W. E., III. (2024). Do traumatic events and substance use co-occur during adolescence? Testing three causal etiologic hypotheses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 65(10), 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, J. D., George, T. P., & Hassan, A. N. (2024). A systematic review of the clinical effects of cannabis and cannabinoids in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and symptom clusters. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 85(1), 51827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Risch, E., Rosner, R., Birkeland, M. S., Eilers, R., Hafstad, G. S., Pfeiffer, E., Plener, P. L., & Jensen, T. K. (2022). The child and adolescent trauma screen 2 (CATS-2)–validation of an instrument to measure DSM-5 and ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Risch, E., Rosner, R., Birkeland, M. S., Eilers, R., Hafstad, G. S., Pfeiffer, E., Plener, P. L., & Jensen, T. K. (2023, October 19). CATS-2 selbsturteil. Available online: https://www.uni-ulm.de/fileadmin/website_uni_ulm/med.cibits/CATS-2_Selbstauskunft.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Saltzman, L. Y., & Terzis, L. (2024). Psychological predictors of the time perspective: The role of posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, and temporal triggers in a sample of bereaved adults. PLoS ONE, 19(3), e0298445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R., & Buckner, R. L. (2007). Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(9), 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P., Dalgleish, T., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). Practitioner review: Posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(5), 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolarski, M., Bitner, J., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Time perspective, emotional intelligence and discounting of delayed awards. Time & Society, 20(3), 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M., & Cyniak-Cieciura, M. (2016). Balanced and less traumatized: Balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between temperament and severity of PTSD syndrome in motor vehicle accident survivor sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M., Zajenkowski, M., Jankowski, K. S., & Szymaniak, K. (2020). Deviation from the balanced time perspective: A systematic review of empirical relationships with psychological variables. Personality and Individual Differences, 156, 109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sword, R. M., Sword, R. K. M., & Brunskill, S. R. (2015). Time perspective therapy: Transforming Zimbardo’s temporal theory into clinical practice. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 481–498). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomich, P. L., & Tolich, A. (2021). Life is a balancing act: Deviation from a balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between lifetime trauma exposure and optimism. Current Psychology, 40(5), 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomich, P. L., Tolich, A., & DeMalio, I. (2022). Strive for balance: Deviation from a balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between lifetime trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms. Current Psychology, 41(11), 8103–8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walg, M. (2017). Stabilisierungstraining für jugendliche Flüchtlinge mit Traumafolgestörungen [Stabilization training for young refugees with trauma-related disorders]. CIP. [Google Scholar]

- Walg, M., Angern, J. S., Michalak, J., & Hapfelmeier, G. (2020a). Wirksamkeit des stabilisierungstrainings für jugendliche flüchtlinge mit traumafolgestörungen: Eine randomisierte kontrollgruppenstudie [Effectiveness of a stabilization training for adolescent refugees with trauma-related disorders: A randomized control group study]. Zeitschrift Für Kinder-Und Jugendpsychiatrie Und Psychotherapie, 48(5), 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walg, M., Eder, L. L., Martin, A., & Hapfelmeier, G. (2020b). Distorted time perspective in adolescent Afghan and Syrian refugees is associated with psychological distress. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 208(9), 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10, 10th edition) (2019th ed., Vol. 10). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell, F. C., Temple, E. C., McKay, M. T., Živkovič, U., Perry, J. L., Mello, Z. R., Musil, B., & Cole, J. C. (2016). A theoretical approach to resolving the psychometric problems associated with the Zimbardo time perspective inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 34(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurgelun-Todd, D. (2007). Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 17(2), 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M., & Ye, Z. (2022). The relationship between intrusive rumination and post-traumatic stress disorder: The mediating role of balanced time perspective. Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology, 6(11), 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The time paradox—The new psychology of time (P. G. Zimbardo, & J. N. Boyd, Eds.; 1st ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P. G., Sword, R., & Sword, R. (2012). The time cure-overcoming PTSD with the new psychology of time perspective therapy (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

| Age in years M ± SD | 15.6 ± 1.3 |

| Sex n (%) | |

| male | 26 (25%) |

| female | 77 (73%) |

| gender diverse | 2 (2%) |

| Clinical setting n (%) | |

| Day clinic | 62 (59%) |

| Outpatient clinic | 43 (41%) |

| Clinical ICD-10 diagnoses n (%) | |

| Unhealthy use of alcohol (F10.1) | 2 (2%) |

| Unhealthy use of cannabis (F12.1/F12.2) | 5 (5%) |

| Unhealthy use of tobacco (F17.2) | 7 (7%) |

| Unhealthy multiple drug use (F19.1) | 1 (1%) |

| Bipolar affective disorder (F31.1) | 1 (1%) |

| Depressive episode (F32) | 43 (41%) |

| Social phobia (F40.1) | 16 (15%) |

| Specific phobia (F40.2) | 2 (2%) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (F42) | 1 (1%) |

| PTSD (F43.1) | 10 (10%) |

| Adjustment disorder (F43.2) | 8 (8%) |

| Somatization disorder (F45.0) | 1 (1%) |

| Anorexia nervosa (F50.0/F50.1) | 3 (3%) |

| Borderline Personality Disorder (F60.31) | 7 (7%) |

| Asperger’s syndrome | 3 (3%) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (F90.0/F90.1) | 31 (30%) |

| Mixed disorders of conduct and emotions (F92) | 5 (5%) |

| Emotional disorders (F93) | 34 (32%) |

| Comorbidity n (%) | 68 (65%) |

| Descriptive Statistics | Spearman Rank Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | PTSS | EPTE | DBTP-r | |

| PTSS | 28.3 | 12.0 | |||

| EPTE | 4.3 | 2.9 | 0.40 *** | ||

| DBTP-r | 5.3 | 0.9 | 0.60 *** | 0.36 *** | |

| Cannabis Use | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.32 *** | 0.27 ** | 0.23 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pütz, A.; Hapfelmeier, G.; Martin, A.; Bender, S.; Walg, M. Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Time Perspective Between Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Cannabis Use. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090177

Pütz A, Hapfelmeier G, Martin A, Bender S, Walg M. Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Time Perspective Between Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Cannabis Use. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090177

Chicago/Turabian StylePütz, Alexander, Gerhard Hapfelmeier, Alexandra Martin, Stephan Bender, and Marco Walg. 2025. "Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Time Perspective Between Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Cannabis Use" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090177

APA StylePütz, A., Hapfelmeier, G., Martin, A., Bender, S., & Walg, M. (2025). Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Time Perspective Between Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Cannabis Use. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090177