Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Survey Administration

2.4. Data Management

2.5. Ethics Approval

2.6. Survey Measures

2.7. Sample Size and Power

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Kidcope

3.3. Item Responses by Gender and Age

3.4. Multivariable Regression Analyses

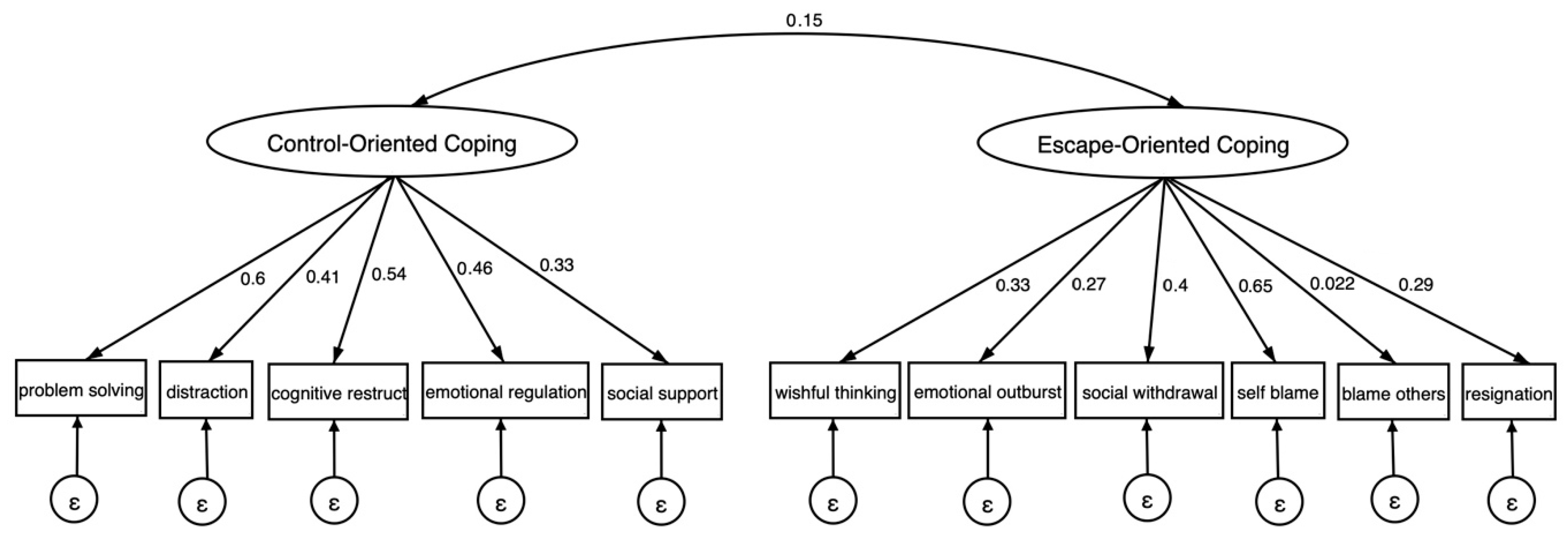

3.5. Structural Equation Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, P., Manjula, M., Rajappa, V., & Phillip, M. (2017). Predictors of non-suicidal and suicidal self-injurious behaviours, among adolescents and young adults in urban India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Lau, H.-P. B., & Chan, M.-P. S. (2014). Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Wang, H.-y., & Ebrahimi, O. V. (2021). Adjustment to a “new normal”: Coping flexibility and mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 626197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T., & Chan, A. C. (2003). Factorial structure of the Kidcope in Hong Kong adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 164(3), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M., Bertomen, S., Njau, P. F., Leiferman, J. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2024a). Dimensions of the KidCope and their associations with mental health outcomes in Tanzanian adolescent orphans. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 12(1), 2288883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M., Doocy, S., Burnham, G., & Glass, N. (2016a). Potentially traumatic events, coping strategies and associations with mental health and well-being measures among conflict-affected youth in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Health Research and Policy, 1(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M., Kohli, A., Remy, M. M., Murhula, C. M., Kurhorhwa, A., Kajabika, B. M., Alfred, B., Bufole, N. M., Banywesize, J. H., Ntakwinja, G. M., Kindja, G. M., & Glass, N. (2015). Coping among trauma-affected youth: A qualitative study. Conflict and Health, 9(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M., Lama, R., Rai, R. P., Dukpa, C., Mukhia, D., Giri, P., & Matergia, M. (2024b). Social support and self-efficacy during early adolescence: Dual impact of protective and promotive links to mental health and wellbeing. PLoS Global Public Health, 4(12), e0003904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M., Tol, W., Burnham, G., Doocy, S., & Glass, N. (2016b). A structural equation model of conflict-affected youth coping and resilience. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., & Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S., Strodl, E., & Sun, H. (2015). Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 5(1), 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, D., Prinstein, M. J., Danovsky, M., & Spirito, A. (2000). Patterns of children’s coping with life stress: Implications for clinicians. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(3), 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlynn, E. S., Miller, S. A., Gaylord-Harden, N. K., & Richards, M. H. (2008). African American inner-city youth exposed to violence: Coping skills as a moderator for anxiety. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(2), 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernestus, S. M., Ellingsen, R., Gray, K., Aralis, H., Lester, P., & Milburn, N. G. (2023). Evaluating the KidCOPE for children in active duty military families. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, C., Vater, A., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2021). Self-compassion and coping: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flament, M. F., Nguyen, H., Furino, C., Schachter, H., MacLean, C., Wasserman, D., Sartorius, N., & Remschmidt, H. (2007). Evidence-based primary prevention programmes for the promotion of mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic worldwide review. In H. Remschmidt, B. Nurcombe, M. L. Belfer, N. Sartorius, & A. Okasha (Eds.), The mental health of children and adolescents: An area of global neglect (pp. 65–136). Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C. (2010). Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: A review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(2), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40(5), 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, P., McGarrigle, L., & Ungar, M. (2019). The CYRM-R: A Rasch-validated revision of the child and youth resilience measure. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(1), 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Hamdan, A. R., Ahmad, R., Mustaffa, M. S., & Mahalle, S. (2016). Problem-solving coping and social support as mediators of academic stress and suicidal ideation among Malaysian and Indian adolescents. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(2), 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, H., & Crombag, A.-C. (2013). What works where? A systematic review of child and adolescent mental health interventions for low and middle income countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(4), 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., & Talwar, R. (2014). Determinants of psychological stress and suicidal behavior in Indian adolescents: A literature review. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 10(1), 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrock, A. M., Compas, B. E., Keller, G., Merchant, M. J., & Copeland, M. E. (2002). Coping with the stress of parental depression: Parents’ reports of children’s coping, emotional, and behavioral problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton, H., Horsley, S., John, S., & Nelson, D. V. (2007). Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 20(6), 977–988. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, N., Khakha, D. C., Qureshi, A., Sagar, R., & Khakha, C. C. (2015). Stress and coping among adolescents in selected schools in the capital city of India. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 82, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K., Brady, M., & Hallman, K. (2016). Investing when it counts: Reviewing the evidence and charting a course of research and action for very young adolescents. Population Council. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mels, C., Derluyn, I., Broekaert, E., & García-Pérez, C. (2015). Coping behaviours and post-traumatic stress in war-affected eastern Congolese adolescents. Stress and Health, 31(1), 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(4), 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R., Sapru, M., Krishna, M., Cuijpers, P., Patel, V., & Michelson, D. (2019). It is like a mind attack: Stress and coping among urban school-going adolescents in India. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T. M., Wegmann, K. M., & Overstreet, S. (2019). Measuring adolescent coping styles following a natural disaster: An ESEM analysis of the Kidcope. School Mental Health, 11(2), 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, B. S., Gururaj, G., Varghese, M., Benegal, V., Rao, G. N., Sukumar, G. M., Amudhan, S., Arvind, B., Girimaji, S., Thennarasu, K., Marimuthu, P., Vijayasagar, K. J., Bhaskarapillai, B., Thirthalli, J., Loganathan, S., Kumar, N., Sudhir, P., Sathyanarayana, V. A., Pathak, K., … Misra, R. (2018). National mental health survey of India, 2016-rationale, design and methods. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0205096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R. P. (2017). Small farmers: Locating them in “Darjeeling Tea”. In Tea technological initiatives (pp. 19–38). New Delhi Publishing Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, L., Pedley, R., Johnson, I., Bell, V., Lovell, K., Bee, P., & Brooks, H. (2022). Conceptualisations of positive mental health and wellbeing among children and adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health Expectations, 25(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., & Wellborn, J. G. (2019). Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. Life-Span Development and Behavior, 12, 91–133. [Google Scholar]

- Spirito, A., Francis, G., Overholser, J., & Frank, N. (1996). Coping, depression, and adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(2), 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirito, A., Stark, L. J., Gil, K. M., & Tyc, V. L. (1995). Coping with everyday and disease-related stressors by chronically iII children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(3), 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławski, K. (2019). The coping circumplex model: An integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, G. (2012). Cultural perspectives on values and religion in adolescent development: A conceptual overview and synthesis. In G. Trommsdorff, & X. Chen (Eds.), Values, religion, and culture in adolescent development (pp. 3–45). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, S.-H., Ku, P.-S., & Luoh, H.-F. (2016). Problem-focused or emotion-focused: Which coping strategy has a better effect on perceived career barriers and choice goals? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., & Swanson, J. (2009). Children’s responses to daily social stressors: Relations with parenting, children’s effortful control, and adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(6), 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernberg, E. M., La Greca, A. M., Silverman, W. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (1996). Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after hurricane Andrew. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigna, J. F., Hernandez, B. C., Kelley, M. L., & Gresham, F. M. (2010). Coping behavior in hurricane-affected African American youth: Psychometric properties of the Kidcope. Journal of Black Psychology, 36(1), 98–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M. E., Ahlkvist, J. A., Jones, D. E., Pham, H., Rajagopalan, A., & Genaro, B. (2022). Targeting the proximal mechanisms of stress adaptation in early adolescence to prevent mental health problems in youth in poverty. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(3), 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M. E., & Compas, B. E. (2002). Coping with family conflict and economic strain: The adolescent perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C. E., Shing, E. Z., & Furr, R. M. (2020). Not all disengagement coping strategies are created equal: Positive distraction, but not avoidance, can be an adaptive coping strategy for chronic life stressors. Anxiety Stress Coping, 33(5), 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Number of Factors | χ2 | (df) | p | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirito et al. (1995) | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lazarus and Folkman (1984) | 2 | 210.77 | 89 | <0.001 | 0.071 | 0.079 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Connor-Smith et al. (2000) | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Valiente et al. (2009) | 2 | 176.46 | 88 | <0.001 | 0.061 | 0.070 | 0.72 | 0.66 |

| S.-T. Cheng and Chan (2003) | 2 | 54.29 | 40 | <0.001 | 0.036 | 0.055 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Male N = 139 | Female N = 135 | Ages | Ages >12.5–14 | Total N = 274 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidcope Items | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | t | p | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | t | p | Mean (SD) |

| Escape-Oriented | |||||||||

| Social Withdrawal | |||||||||

| I stayed by myself | 2.52 (0.10) | 2.84 (0.10) | 2.31 | 0.022 * | 2.77 (0.10) | 2.89 (0.09) | −3.13 | 0.002 ** | 2.68 (0.07) |

| I kept quiet about the problem | 2.76 (0.08) | 2.70 (0.09) | −0.41 | 0.680 | 2.63 (0.09) | 2.83 (0.09) | −1.61 | 0.109 | 2.73 (0.06) |

| Emotional Outburst | |||||||||

| I yelled, screamed, or got mad | 1.77 (0.09) | 2.01 (0.09) | 1.96 | 0.052 | 1.84 (0.09) | 1.94 (0.09) | −0.80 | 0.426 | 1.89 (0.06) |

| Self-Blame | |||||||||

| I blamed myself for causing the problem | 2.44 (0.09) | 2.76 (0.09) | 2.40 | 0.017 * | 2.65 (0.09) | 2.54 (0.10) | 0.87 | 0.386 | 2.59 (0.07) |

| Blaming Others | |||||||||

| I blamed someone else for causing the problem | 2.07 (0.09) | 1.84 (0.08) | −1.83 | 0.068 | 2.01 (0.09) | 1.90 (0.09) | 0.88 | 0.378 | 1.96 (0.06) |

| Wishful Thinking | |||||||||

| I wished the problem had never happened | 3.32 (0.08) | 3.51 (0.07) | 1.79 | 0.075 | 3.49 (0.07) | 3.34 (0.08) | 1.47 | 0.142 | 3.42 (0.05) |

| I wished I could make things different | 3.11 (0.08) | 3.25 (0.07) | 1.31 | 0.191 | 3.14 (0.08) | 3.21 (0.07) | −0.62 | 0.536 | 3.18 (0.05) |

| Resignation | |||||||||

| I didn’t do anything because the problem couldn’t be fixed | 2.35 (0.10) | 2.41 (0.09) | 0.46 | 0.647 | 2.41(0.10) | 2.34 (0.09) | 0.55 | 0.581 | 2.38 (0.07) |

| Control-Oriented | |||||||||

| Distraction | |||||||||

| I just tried to forget it | 2.89 (0.09) | 2.86 (0.08) | −0.28 | 0.782 | 2.93 (0.08) | 2.88 (0.06) | 0.88 | 0.380 | 2.88 (0.06) |

| I did something like played a game to forget it | 3.05 (0.91) | 2.90 (0.09) | −1.32 | 0.188 | 3.04 (0.08) | 2.91 (0.06) | 1.07 | 0.287 | 2.97 (0.06) |

| Cognitive Restructuring | |||||||||

| I tried to see the good side of things | 3.00 (0.08) | 3.04 (0.08) | 0.32 | 0.747 | 3.09 (0.08) | 2.94 (0.09) | 1.34 | 0.182 | 3.02 (0.06) |

| Problem-Solving | |||||||||

| I tried to fix the problem by thinking of answers | 3.10 (0.08) | 3.21 (0.07) | 0.97 | 0.334 | 3.23 (0.07) | 3.07 (0.08) | 1.44 | 0.152 | 3.15 (0.06) |

| I tried to fix the problem by doing something or talking to someone | 2.85 (0.08) | 2.94 (0.08) | 0.79 | 0.432 | 2.99 (0.08) | 2.79 (0.08) | 1.71 | 0.088 | 2.89 (0.06) |

| Emotional Regulation | |||||||||

| I tried to calm myself down | 3.04 (0.79) | 3.14 (0.07) | 0.96 | 0.340 | 3.10 (0.07) | 3.07 (0.08) | 0.26 | 0.794 | 3.09 (0.05) |

| Social Support | |||||||||

| I tried to feel better by spending time with other family or friends | 3.35 (0.07) | 3.36 (0.07) | 0.17 | 0.862 | 3.49 (0.06) | 3.21 (0.08) | 2.79 | 0.003 ** | 3.35 (0.05) |

| Emotional Symptoms | Conduct Problems | Hyperactivity | Peer Problems | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| M1 | |||||||||||||

| Age | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.106 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.087 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.006 ** | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.078 | |

| Sex | −1.88 | 0.27 | 0.000 *** | −0.34 | 0.22 | 0.114 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.994 | −0.25 | 0.24 | 0.287 | |

| M2 | |||||||||||||

| Age | −0.20 | 0.11 | 0.062 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.270 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.035 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.206 | |

| Sex | −1.90 | 0.27 | 0.000 *** | −0.36 | 0.21 | 0.085 | −0.03 | 0.24 | 0.912 | −0.15 | 0.23 | 0.506 | |

| Control-Oriented | −0.43 | −0.91 | 0.365 | −1.45 | 0.35 | 0.000 *** | −1.54 | 0.35 | 0.000 *** | −1.22 | 0.42 | 0.003 ** | |

| Escape-Oriented | 3.24 | 0.50 | 0.000 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.207 | 0.93 | 0.48 | 0.053 | 1.56 | 0.49 | 0.002 | |

| M3 | |||||||||||||

| Age | −0.19 | 0.10 | 0.059 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.399 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.087 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.497 | |

| Sex | −1.60 | 0.26 | 0.000 *** | −0.38 | 0.20 | 0.063 | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.969 | −0.23 | 0.21 | 0.287 | |

| Control-Oriented | −0.24 | 0.52 | 0.649 | −1.11 | 0.40 | 0.006 ** | −1.28 | 0.38 | 0.001 ** | −0.22 | 0.39 | 0.574 | |

| Escape-Oriented | 3.19 | 0.50 | 0.000 *** | −0.44 | 0.44 | 0.323 | 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.108 | 1.43 | 0.48 | 0.003 ** | |

| Friends | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.746 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.323 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.786 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.001 ** | |

| Family | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.450 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.199 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.088 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.004 ** | |

| Significant Others | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.824 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.812 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.834 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.482 | |

| Mental Wellbeing (WHO-5 Wellbeing Index) | Prosocial Behavior (SDQ Subscale) | Resilience (CYRM-R) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| M1 | ||||||||||

| Age | −1.90 | 1.05 | 0.070 | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.012 * | −1.53 | 0.36 | 0.000 *** | |

| Sex | 4.66 | 2.67 | 0.081 | −0.22 | 0.23 | 0.345 | −0.14 | 0.98 | 0.844 | |

| M2 | ||||||||||

| Age | −1.08 | 0.99 | 0.280 | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.060 | −1.12 | 0.34 | 0.001 ** | |

| Sex | 5.00 | 2.56 | 0.052 | −0.05 | 0.21 | 0.805 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.828 | |

| Control-Oriented | 22.66 | 4.04 | 0.000 *** | 1.94 | 0.34 | 0.000 ** | 11.34 | 1.53 | 0.000 *** | |

| Escape-Oriented | −6.38 | 5.27 | 0.227 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.046 * | −1.46 | 1.76 | 0.406 | |

| M3 | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.10 | 0.95 | 0.919 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.373 | −0.50 | 0.30 | 0.099 | |

| Sex | 5.89 | 2.33 | 0.012 ** | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.970 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.299 | |

| Control-Oriented | 11.59 | 3.96 | 0.004 ** | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.001 ** | 4.49 | 1.22 | 0.000 *** | |

| Escape-Oriented | −5.12 | 4.73 | 0.280 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.019 * | 0.04 | 1.29 | 0.976 | |

| Friends | 0.75 | 0.28 | 0.007 ** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.216 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.000 *** | |

| Family | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.004 ** | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.004 ** | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.000 *** | |

| Significant Others | 0.81 | 0.29 | 0.005 ** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.117 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.006 ** | |

| Relationship | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Confidence Interval | t-Statistic | p-Value | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Social Support -> Control-Oriented Coping -> Total Difficulties | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.00 | −2.00 | 0.046 | Supports partial mediation |

| Social Support -> Control-Oriented Coping -> Total Resilience | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 4.29 | <0.001 | Supports partial mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cherewick, M.; Davenport, M.R.; Lama, R.; Giri, P.; Mukhia, D.; Rai, R.P.; Cruz, C.M.; Matergia, M. Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090172

Cherewick M, Davenport MR, Lama R, Giri P, Mukhia D, Rai RP, Cruz CM, Matergia M. Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090172

Chicago/Turabian StyleCherewick, Megan, Madison R. Davenport, Rinzi Lama, Priscilla Giri, Dikcha Mukhia, Roshan P. Rai, Christina M. Cruz, and Michael Matergia. 2025. "Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090172

APA StyleCherewick, M., Davenport, M. R., Lama, R., Giri, P., Mukhia, D., Rai, R. P., Cruz, C. M., & Matergia, M. (2025). Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090172