Emotion Regulation as a Predictor of Disordered Eating Symptoms in Young Female University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

| S-EDE-Q | M | SD | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Cronbach’s α [95% CI] |

| Dietary Restriction (DR) | 1.36 | 1.47 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.876 [0.859–0.892] |

| Eating Concern (EaC) | 1.02 | 1.21 | 5.40 | 0.00 | 5.40 | 0.823 [0.799–0.845] |

| Weight Concern (WC) | 1.88 | 1.59 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.871 [0.853–0.887] |

| Shape Concern (SC) | 2.05 | 1.65 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.933 [0.924–0.941] |

| Total Score (TS) | 6.33 | 5.48 | 22.15 | 0.00 | 22.15 | 0.963 [0.959–0.968] |

| DERS | ||||||

| Emotion Dysregulation (ED) | 19.97 | 8.22 | 36 | 9 | 45 | 0.911 [0.898–0.924] |

| Emotional Rejection (ER) | 15.16 | 6.81 | 28 | 7 | 35 | 0.904 [0.889–0.918] |

| Emotional Interference (EINT) | 12.38 | 4.11 | 16 | 4 | 20 | 0.874 [0.852–0.893] |

| Emotional Inattention (EI) | 14.27 | 3.52 | 16 | 4 | 20 | 0.829 [0.800–0.855] |

| Emotional Confusion (EMC) | 14.39 | 3.44 | 16 | 4 | 20 | 0.825 [0.835–0.876] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales DSM 5 [Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM 5]. Médica Panamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Arija-Val, V., Santi-Cano, M. J., Novalbos-Ruiz, J. P., Canals, J., & Rodríguez-Martín, A. (2022). Caracterización, epidemiología y tendencias de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria [Characterisation, epidemiology and trends in eating disorders]. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 39(2), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berengüí, R., Castejón, M. A., & Torregrosa, M. S. (2016). Body dissatisfaction, risk behaviors eating disorders in university students. Revista Mexicana de Trastornos Alimentarios, 7(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmeyer, T., Grosse Holtforth, M., Bents, H., Kämmerer, A., Herzog, W., & Friederich, H. C. (2012). Starvation and emotion regulation in anorexia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. A., Cusack, A., Berner, L. A., Anderson, L. K., Nakamura, T., Gomez, L., Trim, J., Chen, J. Y., & Kaye, W. H. (2020). Emotion regulation difficulties during and after partial hospitalization treatment across eating disorders. Behavior Therapy, 51(3), 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Sagardoy, R., Solórzano, G., Morales, C., Kassem, M. S., Codesal, R., Blanco, A., & Gallego Morales, L. T. (2014). Procesamiento emocional en pacientes TCA adultas vs. adolescentes. Reconocimiento y regulación emocional [Emotional processing in adult vs. adolescent ED patients. Emotional recognition and regulation]. Clínica y Salud, 25, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-López, V. R., Franco Paredes, K., & Peláez Fernández, M. A. (2021). Influencia de la ansiedad e insatisfacción corporal sobre conductas alimentarias de riesgo en una muestra de mujeres adolescentes de México [Influence of anxiety and body dissatisfaction on risky eating behaviours in a sample of adolescent women in Mexico]. European Journal of Children’s Development, Education and Psychopathology, 9(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, J., & Cifuentes, L. (2012). Uso de curvas ROC en investigación clínica: Aspectos teórico-prácticos [Using ROC curves in clinical investigation. Theoretical and practical issues]. Revista Chilena de Infectología, 29(2), 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. W., Nie, M., Kang, Y. W., He, L. P., Jin, Y. L., & Yao, Y. S. (2015). Subclinical eating disorders in female medical students in Anhui, China: A cross-sectional study. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 31(4), 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clyne, C., Latner, J. D., Gleaves, D. H., & Blampied, N. M. (2010). Treatment of emotional dysregulation in full syndrome and subthreshold binge eating disorder. Eating Disorders, 18(5), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. J., Wells, A., & Todd, G. (2004). A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corstorphine, E. (2006). Cognitive-emotional-behavioural therapy for the eating disorders: Working with beliefs about emotions. European Eating Disorders Review, 14(6), 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş. K., & Aksel, G. (2023). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(4), 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Luz, F. Q., Mohsin, M., Jana, T. A., Marinho, L. S., dos Santos, E., Lobo, I., Pascoareli, L., Gaeta, T., Ferrari, S., Teixeira, P. C., Cordás, T., & Hay, P. (2023). An examination of the relationship between eating disorder symptoms, difficulties with emotion regulation and mental health in people with binge eating disorder. Behavioural Sciences, 13(3), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M., & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. (1988). Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A non-parametric approach. Biometrics, 44(3), 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espeset, E. M., Nordbø, R. H., Gulliksen, K. S., Skårderud, F., Geller, J., & Holte, A. (2011). The concept of body image disturbance in anorexia nervosa: An empirical inquiry utilizing patients’ subjective experiences. Eating Disorders, 19(2), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C. G., & Cooper, Z. (1993). The eating disorder examination. In C. G. Fairburn, & G. T. Wilson (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment (12th ed, pp. 317–360). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fluss, R., Faraggi, D., & Reiser, B. (2005). Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biometrical Journal. Biometrische Zeitschrift, 47(4), 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. R. E., & Froom, K. (2009). Eating disorders: A basic emotion perspective. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(4), 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, A., Austin, A., McClelland, J., Brown, A., Glennon, D., Mountford, V., Grant, N., Allen, K., & Schmidt, U. (2020). First episode rapid early intervention for eating disorders: A two-year follow-up. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Avnon, L., Zubery, E., & Jeczmien, P. (2006). Emotional processing in eating disorders: Specific impairment or general distress related deficiency? Depression and Anxiety, 23(6), 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R., García, P., & Martínez, J. (2013). Valoración de la imagen corporal y de los comportamientos alimentarios en universitarios [Assessment of body image and eating attitudes in university students]. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 18(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gómez, J., Madrazo, I., Gil-Camarero, E., Carral-Fernández, L., Benito-González, P., Calcedo-Giraldo, G., & Gómez del Barrio, A. (2017). Prevalencia, incidencia y factores de riesgo de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en la Comunidad de Cantabria [Prevalence, incidence and risk factors of eating disorders in the Community of Cantabria]. Revista Médica Valdecilla, 2(1), 14–20. Available online: https://repositorio.unican.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10902/13792/Rev%20Med%20Valdecilla_Trastorno%20conducta%20alimentaria.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeno, C. G., Wing, R. R., & Shifman, S. (2000). Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymisławska, M., Puch, E. A., Zawada, A., & Grzymislawski, M. (2020). Do nutritional behaviours depend on biological sex and cultural gender? Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 29(1), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. (2014). Sample size estimation in diagnostic test studies of biomedical informatics. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 48, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynos, A. F., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2011). Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion dysregulation: Evidence and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(3), 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynos, A. F., Roberto, C. A., Martínez, M. A., Attia, E., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2014). Emotion regulation difficulties in anorexia nervosa before and after inpatient weight restoration. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(8), 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervás, G., & Jódar, R. (2008). Adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Dificultades en la regulación emocional [The Spanish version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale]. Clínica y Salud, 19(2), 139–156. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/clinsa/v19n2/v19n2a01.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2017). “Strong beats skinny every time”: Disordered eating and compulsive exercise in women who post fitspiration on Instagram. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(1), 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, N., Tam, D. M., Viet, N. K., Scheib, P., Wirsching, M., & Zeeck, A. (2015). Disordered eating behaviors in university students in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Eating Disorders, 1(3), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender, J., Wonderlich, S., Engel, S., Gordon, K., Kaye, W., & Mitchell, J. (2015). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psycholgy Review, 40, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leehr, E. J., Krohmer, K., Schag, K., Dresler, T., Zipfel, S., & Giel, K. E. (2015). Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity—A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 49, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, D., & Veiga Núñez, O. (2007). Insatisfacción corporal en adolescentes: Relaciones con la actividad física e índice de masa corporal [Body dissatisfaction in adolescents: Relationships with physical activity and body mass index]. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 27, 253–264. Available online: http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista27/artinsatisfaccion41e.htm (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- McClelland, J., Hodsoll, J., Brown, A., Lang, K., Boysen, E., Flynn, M., Mountford, V. A., Glennon, D., & Schmidt, U. (2018). A pilot evaluation of a novel first episode and rapid early intervention service for eating disorders (FREED). European Eating Disorders Review, 26(2), 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnick, S. M., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2000). Emotion regulation and parenting in AD/HD and comparison boys: Linkages with social behaviors and peer preference. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28(1), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monell, E., Clinton, D., & Birgegård, A. (2018). Emotion dysregulation and eating disorders-associations with diagnostic presentation and key symptoms. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(8), 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monell, E., Högdahl, L., Mantilla, E. F., & Birgegård, A. (2015). Emotion dysregulation, self-image and eating disorder symptoms in University Women. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L. R., Halpern-Felsher, B. L., Nagata, J. M., & Carlson, J. L. (2021). Clinician practices assessing hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis suppression in adolescents with an eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(12), 2218–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, W., Devonport, T. J., & Blake, M. (2016). The association between emotions and eating behaviour in an obese population with binge eating disorder. Obesity Reviews, 17(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Fernández, M. A., Labrador, F. J., & Raich, R. M. (2012). Validation of the Spanish version of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) for the screening of eating disorders in community samples. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Fernández, M. A., Labrador, F. J., & Raich, R. M. (2013). Norms for the Spanish version of the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (S-EDE-Q). Psicothema, 25, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preyde, M., Watson, J., Remers, S., & Stuart, R. (2016). Emotional dysregulation, interoceptive deficits, and treatment outcomes in patients with eating disorders. Social Work in Mental Health, 14, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, S. E., & Wildes, J. E. (2013). Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anorexia nervosa: The unique roles of lack of emotional awareness and impulse control difficulties when upset. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ruíz, S., Díaz, S., Ortega-Roldán, B., Mata, J. L., Delgado, R., & Fernández-Santaella, M. C. (2013). La insatisfacción corporal y la presión de la familia y del grupo de iguales como factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria [Body dissatisfaction, family and peer pressure as risk factors for the development of eating disorders]. Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de la Salud, 9, 21–23. Available online: https://idus.us.es/server/api/core/bitstreams/79c78a62-633c-42de-9ba1-cdaf9b1c46ac/content (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Roos, C. R., Sala, M., Kober, H., Vanzhula, I. A., & Levinson, C. A. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions for eating disorders: The potential to mobilize multiple associative-learning change mechanisms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(9), 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowsell, M., MacDonald, D. E., & Carter, J. C. (2016). Emotion regulation difficulties in anorexia nervosa: Associations with improvements in eating psychopathology. Journal of Eating Disorder, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rø, Ø., Reas, D. L., & Stedal, K. (2015). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in Norwegian adults: Discrimination between female controls and eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 23(5), 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lázaro, P. M., Comet, M. P., Calvo, A. I., Zapata, M., Cebollada, L., Trébol, L., & Lobo, A. (2010). Prevalencia de trastornos alimentarios en estudiantes adolescentes tempranos [Prevalence of eating disorders in preteen students]. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 38(4), 204–211. Available online: https://actaspsiquiatria.es/index.php/actas/article/view/792/1243 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Sala, M., Levinson, C. A., Kober, H., & Roos, C. R. (2023). A pilot open trial of a digital mindfulness-based intervention for anorexia nervosa. Behavior Therapy, 54(4), 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, H. B., Clancy, O. M., Gomez, M. M., Cero, I., Smith, A. R., Brown, T. A., & Witte, T. K. (2024). The relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and eating disorder outcomes: A longitudinal examination in a residential eating disorder treatment facility. Eating Disorders, 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Serralta, M., Perpiñá, C., Císcar, S., Blasco, L., Espert, R., Romero-Escobar, C., Domínguez, J. R., & Oltra-Cucarella, J. (2019). Funciones ejecutivas y regulación emocional en obesidad y trastornos alimentarios [Executive functions and emotional regulation in obesity and eating disorders]. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 36(1), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproesser, G., Klusmann, V., Ruby, M. B., Arbit, N., Rozin, P., Schupp, H. T., & Renner, B. (2018). The positive eating scale: Relationship with objective health parameters and validity in Germany, the USA and India. Psychology & Health, 33(3), 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R. I., Kenardy, J., Wiseman, C. V., Dounchis, J. Z., Arnow, B. A., & Wilfey, D. E. (2007). What’s driving the binge in binge eating disorder? A prospective examination of precursors and consequences. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 40(3), 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysko, R., Glasofer, D., Hildebrant, T., Klimek, P., Mitchell, J., Berg, K., Peterson, C., Wonderlich, S., & Walsh, T. (2015). The eating disorder assessment for DSM-5 (EDA-5): Development and validation of a structured interview for feeding and eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(5), 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. In N. A. Fox (Ed.), The development of emotion regulation: Biological and Behavioral Considerations (vol. 59, pp. 25–52). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, N., Bussey, K., Forbes, M. K., Hay, P., Goldstein, M., Thornton, C., Basten, C., Heruc, G., Roberts, M., Byrne, S., Griffiths, S., Lonergan, A., & Mitchison, D. (2022). Emotion dysregulation and eating disorder symptoms: Examining distinct associations and interactions in adolescents. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(5), 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T., Herman, C. P., & Verheijden, M. W. (2014). Dietary restraint and body mass change. A 3-year follow up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite, 76, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Ayala, K. S., & González-Ramírez, M. T. (2020). Influencias sociales en un modelo de insatisfacción corporal, preocupación por el peso y malestar corporal en mujeres mexicanas [Social influences in a model of body dissatisfaction, weight worry and bodily discomfort in Mexican women]. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 23(1), 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögele, C., & Gibson, L. (2010). Mood, emotions and eating disorders. In W. S. Agras (Ed.), Handbook of eating disorders (pp. 180–205). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Youden, W. J. (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3(1), 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DERS | S-EDE-Q | ||||

| DR | EaC | WC | SC | TS | |

| ED | 0.291 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.386 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.402 ** |

| ER | 0.283 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.381 ** |

| EINT | 0.169 ** | 0.266 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.248 ** |

| EI | −0.100 * | −0.193 ** | −0.191 ** | −0.176 ** | −0.178 ** |

| EC | −0.238 ** | −0.396 ** | −0.344 ** | −0.352 ** | −0.358 ** |

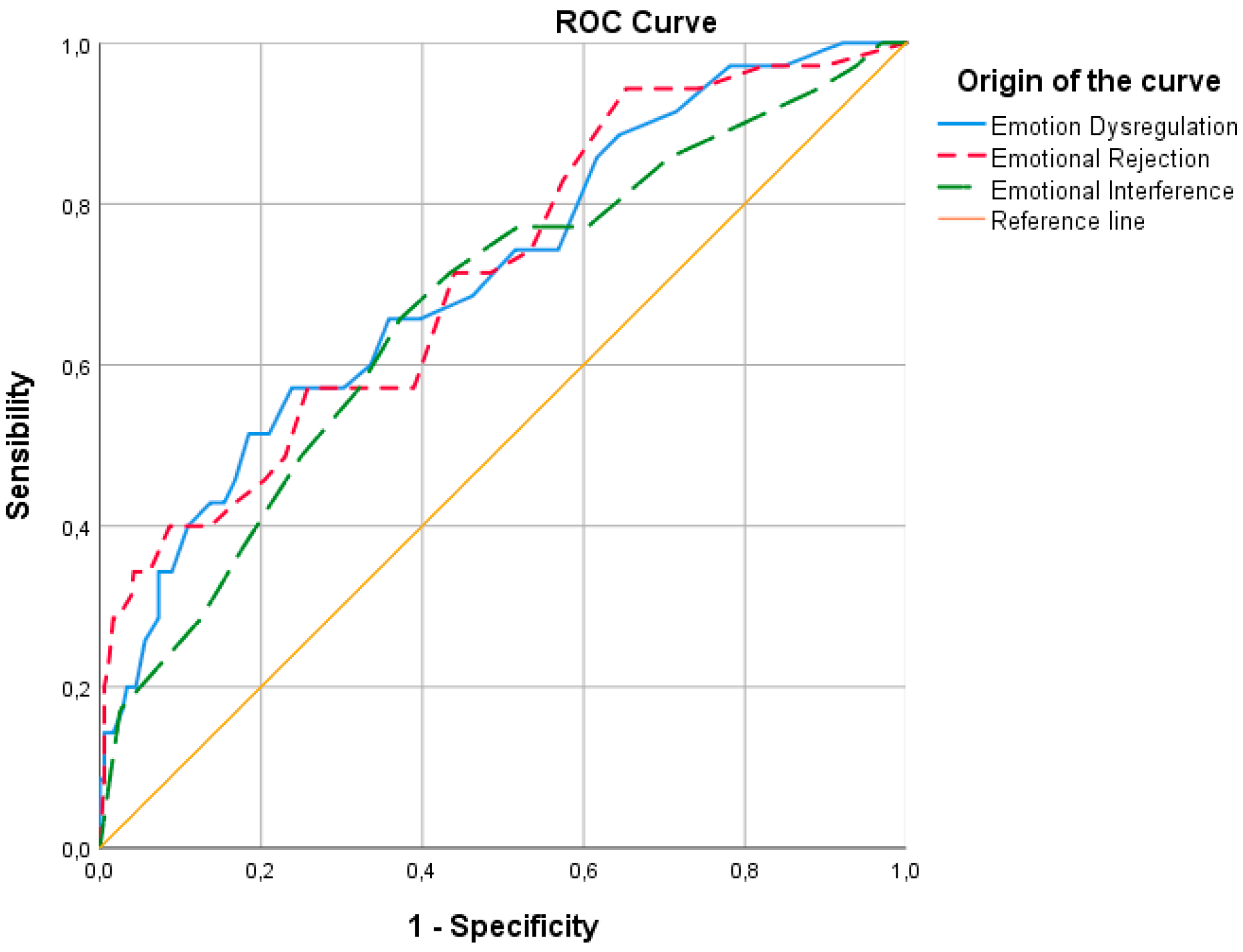

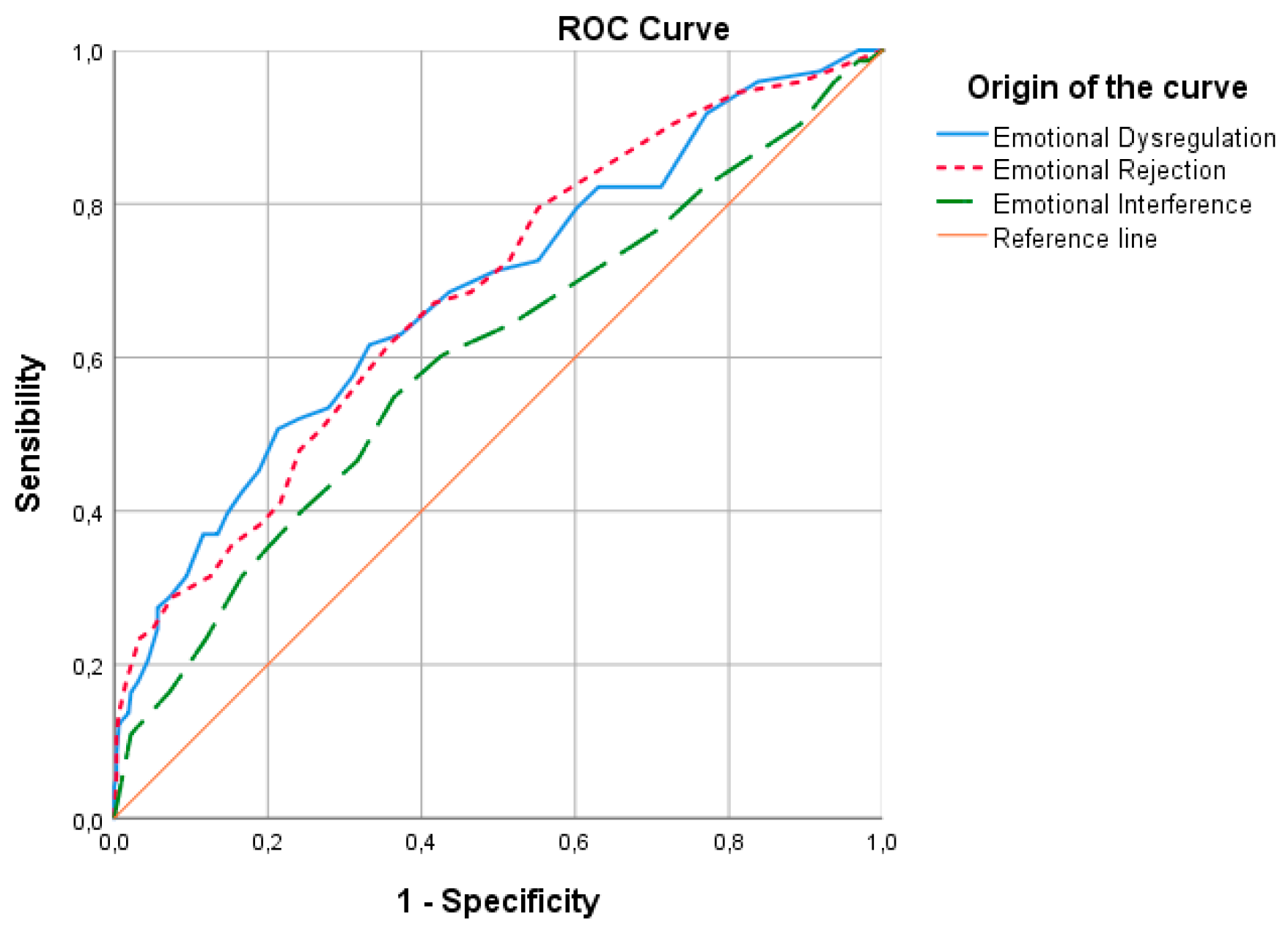

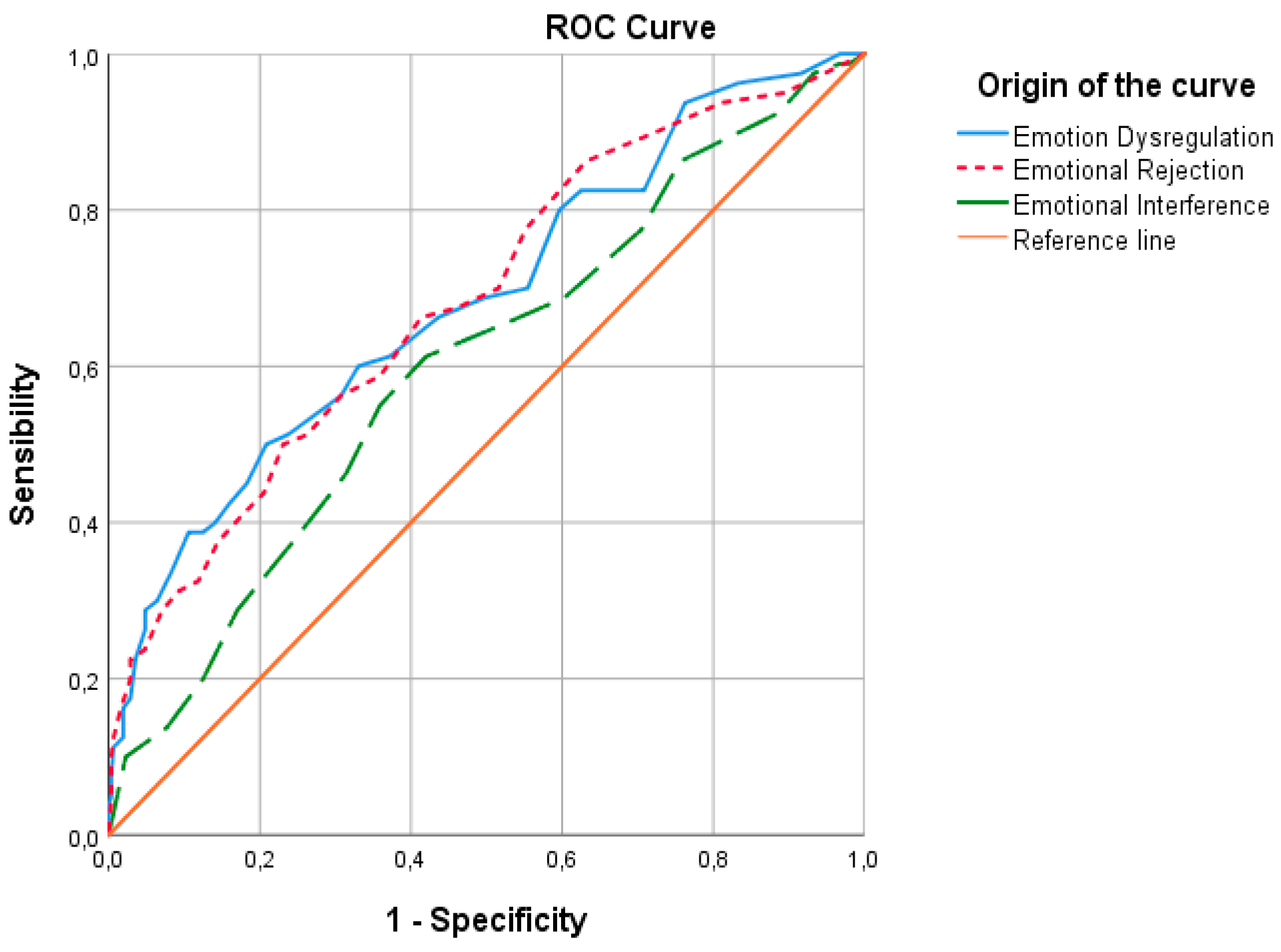

| Predictor | Criteria | Cut-Off Point | Sensitivity | 95% CI | 1—Specificity | 95% CI | Youden Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Dysregulation | Dietary Restriction | 16.5 ** | 0.743 | 0.567–0.875 | 0.569 | 0.379–0.484 | 0.174 |

| 17.5 | 0.743 | 0.515 | 0.227 | ||||

| 18.5 * | 0.686 | 0.462 | 0.224 | ||||

| Eating Concern | 20.5 ** | 0.857 | 0.636–0.969 | 0.358 | 0.590–0.690 | 0.499 | |

| 21.5 * | 0.810 | 0.334 | 0.475 | ||||

| Weight Concern | 18.5 ** | 0.685 | 0.565–0.788 | 0.436 | 0.507–0.619 | 0.249 | |

| Shape Concern | 17.5 ** | 0.688 | 0.574–0.786 | 0.497 | 0.446–0.560 | 0.191 | |

| 18.5 * | 0.663 | 0.436 | 0.227 | ||||

| Emotional Rejection | Dietary Restriction | 13.5 ** | 0.714 | 0.537–0.853 | 0.485 | 0.462–0.568 | 0.230 |

| 14.5 * | 0.614 | 0.440 | 0.275 | ||||

| Eating Concern | 14.5 ** | 0.857 | 0.636–0.969 | 0.442 | 0.505–0.609 | 0.415 | |

| Weight Concern | 13.5 ** | 0.685 | 0.565–0.788 | 0.464 | 0.479–0.591 | 0.221 | |

| Shape Concern | 12.5 ** | 0.700 | 0.589–0.797 | 0.516 | 0.427–0.541 | 0.184 | |

| 13.5 * | 0.675 | 0.462 | 0.213 | ||||

| Emotional Interference | Dietary Restriction | 12.5 ** | 0.714 | 0.537–0.853 | 0.434 | 0.512–0.617 | 0.280 |

| 13.5 * | 0.657 | 0.373 | 0.285 | ||||

| Eating Concern | 13.5 ** | 0.762 | 0.528–0.917 | 0.377 | 0.571–0.672 | 0.385 | |

| Weight Concern | 12.5 ** | 0.603 | 0.481–0.715 | 0.426 | 0.517–0.628 | 0.176 | |

| 13.5 * | 0.548 | 0.364 | 0.184 | ||||

| Shape Concern | 12.5 ** | 0.613 | 0.497–0.719 | 0.420 | 0.523–0.635 | 0.193 | |

| 13.5 * | 0.550 | 0.329 | 0.191 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Valverde, M.; Felipe-Castaño, E. Emotion Regulation as a Predictor of Disordered Eating Symptoms in Young Female University Students. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090171

Rojas-Valverde M, Felipe-Castaño E. Emotion Regulation as a Predictor of Disordered Eating Symptoms in Young Female University Students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(9):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090171

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Valverde, Marina, and Elena Felipe-Castaño. 2025. "Emotion Regulation as a Predictor of Disordered Eating Symptoms in Young Female University Students" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 9: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090171

APA StyleRojas-Valverde, M., & Felipe-Castaño, E. (2025). Emotion Regulation as a Predictor of Disordered Eating Symptoms in Young Female University Students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(9), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15090171