The Role of Social Functioning Between Vitality and Mental Distress in Hypertension: A Partial Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Comparison Between Clinical and Non-Clinical Patients

3.2. Correlations Between the Clinical Variables

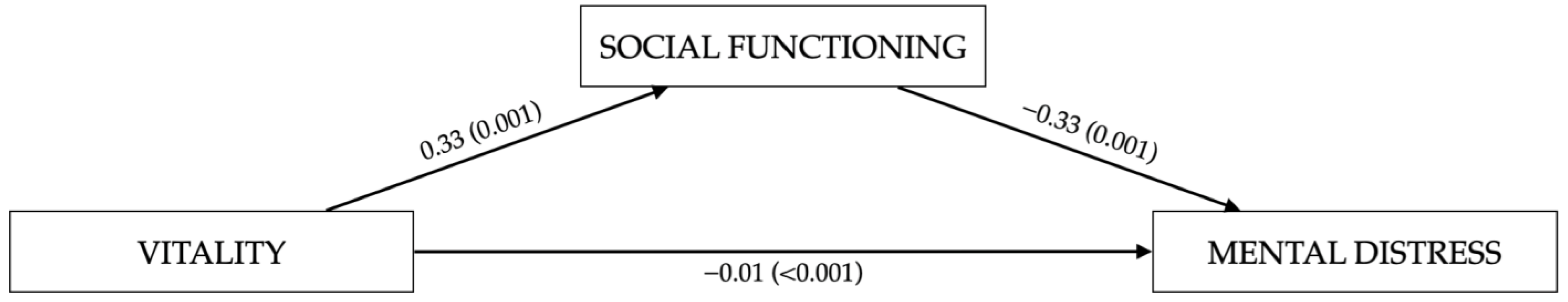

3.3. Serial Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acton, G. J., & Malathum, P. (2000). Basic need status and health-promoting self-care behavior in adults. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(7), 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apolone, G., & Mosconi, P. (1998). The Italian SF-36 health survey: Translation, validation and norming. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arija, V., Villalobos, F., Pedret, R., Vinuesa, A., Jovani, D., Pascual, G., & Basora, J. (2018). Physical activity, cardiovascular health, quality of life and blood pressure control in hypertensive subjects: Randomized clinical trial. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B., Yin, H., Guo, L., Ma, H., Wang, H., Liu, F., Liang, Y., Liu, A., & Geng, Q. (2021). Comorbidity of depression and anxiety leads to a poor prognosis following angina pectoris patients: A prospective study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaguidi, F., Michelassi, C., Trivella, M. G., Carpeggiani, C., Pruneti, C. A., Cesana, G., & L’Abbate, A. (1996). Cattell’s 16 PF and PSY inventory: Relationship between personality traits and behavioral responses in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira-Míguez, M., Ramos-Campo, D. J., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2022). Differences in nutritional and psychological habits in hypertension patients. BioMed Research International, 2022, 1920996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colivicchi, F., Abrignani, M. G., & Santini, M. (2010). Aderenza terapeutica: Il fattore di rischio occulto [Therapeutic non-adherence: The hidden risk factor]. Giornale italiano di cardiologia (2006), 11(5 Suppl. 3), 124S–127S. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1994). SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R., & Svitz, K. L. (1999). The SCL-90-R, Brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, K. A., Dion-Albert, L., Kaufmann, F. N., Tuck, E., Lebel, M., & Menard, C. (2021). Neurobiology of resilience in depression: Immune and vascular insights from human and animal studies. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 53(1), 183–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M. S., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. (2017). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, M. S., Kunjummen, E., Hussain, M. S., Nasereldin, M., Bennett, S., & Miller, J. (2020). Anxiety, depression, and pain: Considerations in the treatment of patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Current Hypertension Reports, 22(12), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, U., Kjeldsen, L. J., Pottegård, A., Henriksen, J. E., Lambrechtsen, J., Hangaard, J., & Hallas, J. (2015). Improving medication adherence in patients with hypertension: A randomized trial. The American Journal of Medicine, 128(12), 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holahan, C. K., & Suzuki, R. (2004). Adulthood predictors of health-promoting behavior in later aging. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 58(4), 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryn, K., Sydorenko, A., Vlasova, O., Kolot, E., & Martynenko, Y. (2021). Clinical, pharmacotherapeutic and biorhythmological peculiarities of depressive disorders, comorbid with cardiovascular pathology. Georgian Medical News, 312, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanušić Pejić, D., & Degmečić, D. (2022). Hypertension in association with anxiety and depression—A narrative review. Southeastern European Medical Journal, 6(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretchy, I. A., Owusu-Daaku, F. T., & Danquah, S. A. (2014). Mental health in hypertension: Assessing symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress on anti-hypertensive medication adherence. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(25), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupper, N., & Denollet, J. (2018). Type D personality as a risk factor in coronary heart disease: A review of current evidence. Current Cardiology Reports, 20(11), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E., Dawood, T., Straznicky, N., Sari, C., Schlaich, M., Esler, M., & Lambert, G. (2010). Association between the sympathetic firing pattern and anxiety level in patients with the metabolic syndrome and elevated blood pressure. Journal of Hypertension, 28(3), 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., Kim, K. I., & Cho, M. C. (2019). Current status and therapeutic considerations of hypertension in the elderly. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, 34(4), 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Yu, J., Chen, X., Quan, X., & Zhou, L. (2018). Correlations between health-promoting lifestyle and health-related quality of life among elderly people with hypertension in Hengyang, Hunan, China. Medicine, 97(25), e10937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F., Versino, E., Gammino, L., Colombi, N., Ostacoli, L., Carletto, S., Furlan, P. M., & Picci, R. L. (2016). Type D personality and essential hypertension in primary care: A cross-sectional observational study within a cohort of patients visiting general practitioners. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(1), 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Player, M. S., Mainous, A. G., 3rd, & Carnemolla, M. (2008). Anxiety and unrecognized high blood pressure in U.S. ambulatory care settings: An analysis of the 2005 national ambulatory medical care survey and the national hospital ambulatory medical care survey. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 38(1), 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polishchuk, O. Y., Tashchuk, V. K., Barchuk, N. I., Amelina, T. M., Hrechko, S. I., & Trefanenko, I. V. (2021). Anxiety and depressive disorders in patients with arterial hypertension. Wiadomosci lekarskie, 74(3 cz 1), 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2003). Social Engagement and Attachment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1008(1), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2009). The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 76(Suppl. 2), S86–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2021). Polyvagal theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 7, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunas, A., Sarno, I., Preti, E., Madeddu, F., & Perugini, M. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R: A study on a large community sample. European Psychiatry, 27(8), 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruneti, C., Giusti, M., Boem, A., & Luisi, M. (2002). Behavioral, psycho-physiological and salivary cortisol modifications after short-term alprazolam treatment in patients with recent myocardial infarction. Italian Heart Journal: Official Journal of the Italian Federation of Cardiology, 3(1), 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, M., Shah, G., Asif, M., Shah, A., Adhikari, K., & Abu-Shaheen, A. (2021). Factors associated with hypertension in Pakistan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0246085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendorff, C., Black, H. R., Cannon, C. P., Gersh, B. J., Gore, J., Izzo, J. L., Jr., Kaplan, N. M., O’Connor, C. M., O’Gara, P. T., Oparil, S., American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology & American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. (2007). Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation, 115(21), 2761–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenman, R. H. (1991). Type A behavior pattern and coronary heart disease: The hostility factor? Stress Medicine, 7, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavoni, M., Pruneti, C., Guidotti, S., Moscatello, A., Giordano, F., Coluccia, A., Santoro, R. C., Mansueto, M. F., Zanon, E., Marino, R., Cantori, I., & De Cristofaro, R. (2023). Health-related quality of life and psychopathological symptoms in people with hemophilia, bloodborne co-infections and comorbidities: An italian multicenter observational study. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases, 15(1), e2023005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A. C., Borges, J. W., & Moreira, T. M. (2016). Quality of life and treatment adherence in hypertensive patients: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Revista de Saude Publica, 50, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D., & Bernabe-Ortiz, A. (2020). Association between arterial hypertension and depressive symptoms: Results from population-based surveys in Peru. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists, 12(2), e12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, P. H., & von Känel, R. (2017). Psychological stress, inflammation, and coronary heart disease. Current Cardiology Reports, 19(11), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2013). A global brief on hypertension: Silent killer, global public health crisis: World Health Day 2013 (No. WHO/DCO/WHD/2013.2). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Non-Clinical Group (n = 50) | Clinical Group (n = 50) | Total Sample (n = 100) | t or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 55 (11.4) | 57.1 (12.7) | 56.04 (12.04) | t (98) = −0.88 | 0.48 | |

| Sex, N (%) | χ2 (1, n = 100) = 6.79 | 0.01 | ||||

| Male | 32 (32%) | 17 (17%) | 49 (49%) | |||

| Female | 19 (19%) | 32 (32%) | 51 (51%) | |||

| Marital status, N (%) | χ2 (3, n = 100) = 4.81 | 0.18 | ||||

| Married/cohabitating | 44 (44%) | 42 (42%) | 86 (86%) | |||

| Unmarried | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (5%) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 1 (1%) | 5 (5%) | 6 (6%) | |||

| Widowed | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | |||

| Education Level, N (%) | χ2 (2, n = 100) = 5.36 | 0.07 | ||||

| Middle school graduation | 25 (25%) | 35 (35%) | 60 (60%) | |||

| High school graduation | 20 (20%) | 10 (10%) | 30 (30%) | |||

| University degree | 6 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 10 (10%) | |||

| Current Occupation, N (%) | χ2 (3, n = 100) = 1.24 | 0.74 | ||||

| Student | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |||

| Employed | 29 (29%) | 27 (27%) | 56 (56%) | |||

| Not employed | 8 (8%) | 9 (9%) | 17 (17%) | |||

| Retired | 14 (14%) | 12 (12%) | 26 (26%) | |||

| Non-Clinical Group (n = 50) | Clinical Group (n = 50) | Total Sample (n = 100) | t (98) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | |||||||||

| Somatization | 52.28 | 8.61 | 70.72 | 18.01 | 61.32 | 16.79 | −7.54 | <0.001 | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | 48.35 | 7.28 | 64.73 | 14.31 | 56.38 | 13.92 | −8.11 | <0.001 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 46.38 | 4.98 | 55.85 | 12.64 | 51.02 | 10.61 | −5.11 | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 49.77 | 8.78 | 64.40 | 15.92 | 56.94 | 14.69 | −7.13 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety | 50.21 | 8.07 | 66.66 | 16.42 | 58.27 | 15.23 | −7.41 | <0.001 | |

| Hostility | 47.58 | 6.99 | 55.01 | 10.01 | 51.22 | 9.34 | −5.81 | <0.001 | |

| Phobic anxiety | 47.84 | 3.87 | 58.29 | 18.75 | 52.96 | 14.34 | −3.93 | <0.001 | |

| Paranoid ideation | 47.63 | 6.09 | 60.83 | 16.21 | 54.10 | 13.78 | −5.92 | <0.001 | |

| Psychoticism | 47.77 | 5.08 | 62.28 | 17.19 | 54.88 | 14.47 | −6.08 | <0.001 | |

| 36-item Short Form Health Survey | |||||||||

| Physical functioning | 90.88 | 12.80 | 77.65 | 19.64 | 84.40 | 17.71 | 4.36 | <0.001 | |

| Bodily pain | 79.88 | 23.90 | 58.20 | 27.12 | 69.26 | 27.63 | 4.61 | <0.001 | |

| General health | 55.06 | 11.46 | 54.71 | 12.67 | 54.89 | 12.01 | 0.26 | 0.28 | |

| Vitality | 69.61 | 17.97 | 50.51 | 21.70 | 60.25 | 21.51 | 5.89 | <0.001 | |

| Social functioning | 81.18 | 13.89 | 60.51 | 26.80 | 71.05 | 23.52 | 5.00 | <0.001 | |

| Mental health | 76.00 | 16.04 | 56.82 | 21.73 | 66.60 | 21.25 | 5.97 | <0.001 | |

| Medical Measurements | |||||||||

| Cortisol (in μg/dL) | 14.42 | 4.76 | 15.76 | 4.19 | 15.05 | 4.52 | −1.32 | 0.050 | |

| Heart Rate (in bpm) | 69.17 | 8.47 | 69.73 | 9.86 | 69.43 | 14.47 | −0.29 | 0.39 | |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cortisol | 15.05 | 4.52 | - | |||||||

| 2. Heart Rate | 69.43 | 9.09 | - | |||||||

| 3. SCL-90-R GSI | 0.54 | 0.46 | - | - | ||||||

| 4. SF-36 PF | 84.40 | 17.71 | - | 0.24 * | −0.33 ** | |||||

| 5. SF-36 BP | 69.26 | 27.63 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 6. SF-36 GH | 54.12 | 12.01 | - | - | −0.19 * | - | - | |||

| 7. SF-36 VT | 60.25 | 21.51 | - | 0.19 * | −0.51 * | 0.53 ** | - | - | ||

| 8. SF-36 SF | 71.05 | 23.52 | - | - | −0.48 ** | 0.53 ** | - | - | 0.50 ** | |

| 9. SF-36 MH | 66.60 | 21.25 | - | - | −0.66 ** | 0.40 ** | - | 0.72 ** | 0.59 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guidotti, S.; Giordano, F.; Pruneti, C. The Role of Social Functioning Between Vitality and Mental Distress in Hypertension: A Partial Mediation Model. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050072

Guidotti S, Giordano F, Pruneti C. The Role of Social Functioning Between Vitality and Mental Distress in Hypertension: A Partial Mediation Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050072

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuidotti, Sara, Francesca Giordano, and Carlo Pruneti. 2025. "The Role of Social Functioning Between Vitality and Mental Distress in Hypertension: A Partial Mediation Model" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050072

APA StyleGuidotti, S., Giordano, F., & Pruneti, C. (2025). The Role of Social Functioning Between Vitality and Mental Distress in Hypertension: A Partial Mediation Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050072