Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mental Health and Turnover Intention Among Health Workers at Different Occupational Statuses: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Measures

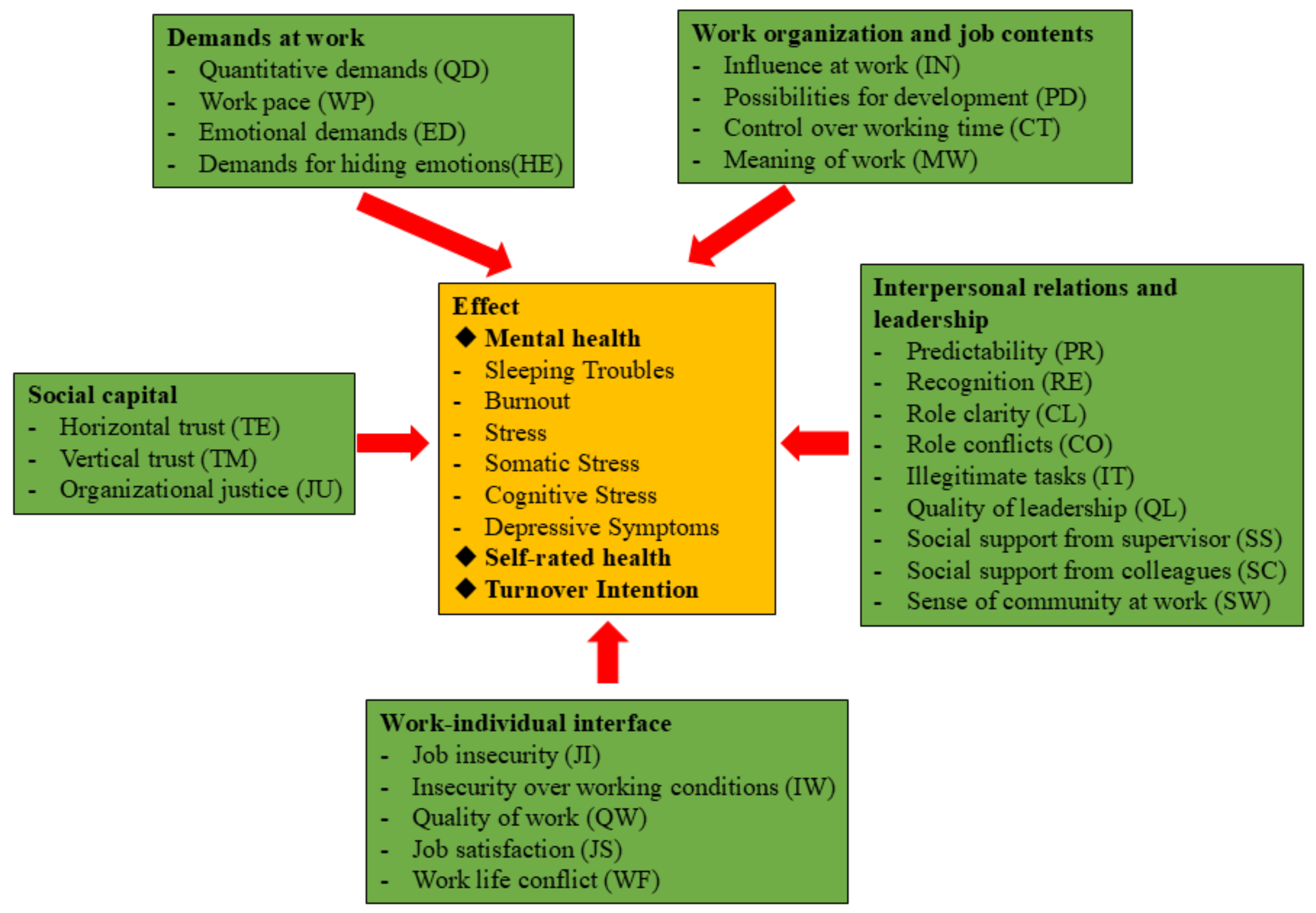

2.2.1. Psychosocial Factors

2.2.2. Mental Health Issues

2.2.3. General Health

2.2.4. Turnover Intention

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Health Workers

3.2. The COPSOQ III: Descriptive Statistics of Dimensions

3.3. The COPSOQ III: General Psychosocial Exposure by Occupational Status

3.4. Mental Health and Turnover Intention by Occupational Status

3.5. Consequences of Psychosocial Exposure

| Domain | Dimension | Sleeping | Burnout | Stress | Depressive | Total Mental | General Health | Turnover Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at Work | QD | 0.274 *** | 0.388 *** | 0.369 *** | 0.384 *** | 0.404 *** | −0.186 *** | 0.294 *** |

| WP | 0.265 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.303 *** | 0.207 *** | 0.321 *** | −0.213 *** | 0.175 *** | |

| ED | 0.333 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.429 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.455 *** | −0.194 *** | 0.286 *** | |

| HE | 0.294 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.328 *** | 0.253 *** | 0.360 *** | −0.199 *** | 0.221 *** | |

| Work Organization and Job Contents | IN | 0.107 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.153 *** | 0.146 *** | 0.040 | 0.089 ** |

| PD | −0.124 *** | −0.160 *** | −0.157 *** | −0.146 *** | −0.168 *** | 0.165 *** | −0.076 * | |

| CT | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.047 | 0.167 *** | 0.074 * | 0.077 * | 0.099 ** | |

| MW | −0.111 *** | −0.155 *** | −0.177 *** | −0.236 *** | −0.193 *** | 0.062 * | −0.126 *** | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | PR | −0.095 ** | −0.131 *** | −0.101 ** | −0.060 | −0.111 *** | 0.153 *** | −0.058 |

| RE | −0.136 *** | −0.205 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.194 *** | −0.213 *** | 0.167 *** | −0.139 *** | |

| CL | −0.157 *** | −0.219 *** | −0.225 *** | −0.280 *** | −0.251 *** | 0.145 *** | −0.148 *** | |

| CO | 0.206 *** | 0.275 *** | 0.275 *** | 0.219 *** | 0.279 *** | −0.070 * | 0.139 *** | |

| IT | 0.238 *** | 0.347 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.329 *** | −0.115 *** | 0.199 *** | |

| QL | −0.127 *** | −0.159 *** | −0.172 *** | −0.164 *** | −0.178 *** | 0.215 *** | −0.064 * | |

| SS | −0.101 ** | −0.162 *** | −0.185 *** | −0.129 *** | −0.164 *** | 0.191 *** | −0.137 *** | |

| SC | −0.088 ** | −0.131 *** | −0.150 *** | −0.176 *** | −0.155 *** | 0.125 *** | −0.075 * | |

| SW | −0.158 *** | −0.206 *** | −0.229 *** | −0.262 *** | −0.244 *** | 0.167 *** | −0.111 *** | |

| Work–Individual Interface | JI | 0.218 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.264 *** | 0.282 *** | 0.291 *** | −0.121 *** | 0.105 ** |

| IW | 0.273 *** | 0.349 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.290 *** | 0.360 *** | −0.147 *** | 0.166 *** | |

| QW | −0.095 ** | −0.122 *** | −0.142 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.151 *** | 0.156 *** | −0.085 ** | |

| JS | −0.186 *** | −0.287 *** | −0.273 *** | −0.231 *** | −0.279 *** | 0.235 *** | −0.220 *** | |

| WF | 0.359 *** | 0.498 *** | 0.456 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.493 *** | −0.218 *** | 0.235 *** | |

| Social Capital | TE | −0.106 ** | −0.169 *** | −0.189 *** | −0.164 *** | −0.179 *** | 0.096 *** | −0.096 *** |

| TM | −0.131 *** | −0.188 *** | −0.206 *** | −0.175 *** | −0.199 *** | 0.146 *** | −0.118 *** | |

| JU | −0.159 *** | −0.239 *** | −0.260 *** | −0.210 *** | −0.248 *** | 0.191 *** | −0.108 *** |

3.5.1. Mental Health Issues

3.5.2. General Health

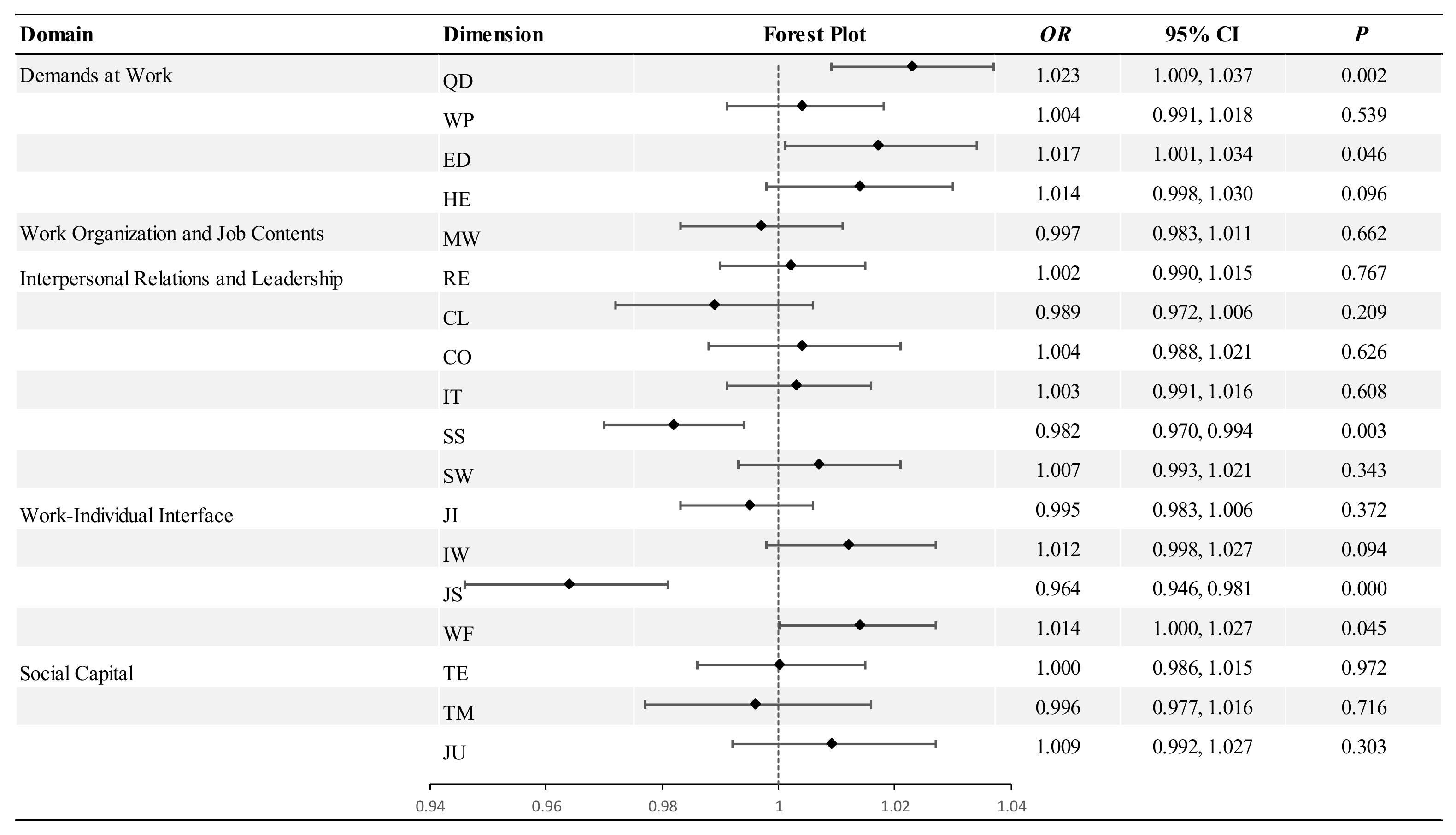

3.5.3. Turnover Intention

4. Discussion

4.1. Chinese and International HWs Experienced Different Psychosocial Stressors

4.2. Associations Between Psychosocial Factors and Health-Rated Outcomes Across Occupational Statuses

4.3. Effect of Psychosocial Stressors on Turnover Intention

4.4. Intervention Recommendations for Addressing Psychosocial Factors

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

| HWs | Health Workers |

| ILO | The International Labour Organization |

| COPSOQ III | Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III |

References

- Al Dilby, H. K., & Farmanesh, P. (2023). Exploring the impact of virtual leadership on job satisfaction in the post-COVID-19 era: The mediating role of work-life balance and trust in leaders. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 994539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anger, W. K., Dimoff, J. K., & Alley, L. (2024). Addressing health care workers’ mental health: A systematic review of evidence-based interventions and current resources. American Journal of Public Health, 114(S2), 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorner, J. B., & Pejtersen, J. H. (2010). Evaluating construct validity of the second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire through analysis of differential item functioning and differential item effect. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(Suppl. S3), 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burr, H., Berthelsen, H., Moncada, S., Nübling, M., Dupret, E., Demiral, Y., Oudyk, J., Kristensen, T. S., Llorens, C., Navarro, A., Lincke, H.-J., Bocéréan, C., Sahan, C., Smith, P., & Pohrt, A. (2019). The third version of the copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Safety and Health at Work, 10(4), 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P., & Phungsoonthorn, T. (2021). The effectiveness of supervisor support in lessening perceived uncertainties and emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis: The constraining role of organizational intransigence. The Journal of General Psychology, 148(4), 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COPSOQ International Network. (2019). COPSOQ III-Guidelines and questionnaire. COPSOQ International Network. Available online: https://www.copsoq-network.org/licence-guidelines-and-questionnaire/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Duan, X., Ni, X., Shi, L., Zhang, L., Ye, Y., Mu, H., Li, Z., Liu, X., Fan, L., & Wang, Y. (2019). The impact of workplace violence on job satisfaction, job burnout, and turnover intention: The mediating role of social support. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, C. M., Roche, M. A., Homer, C., Buchan, J., & Dimitrelis, S. (2014). A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(12), 2703–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Johnson, P. O., Cipriano, P. F., Beatty, D. E., Peterson, C., Major-Elechi, B., & Shanafelt, T. (2019). Burnout and satisfaction with work–life integration among nurses. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(8), 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicia, F., Sudibjo, N., & Harsanti, H. R. (2023). Impact of psychosocial risk on intention to leave work during COVID-19 in Indonesia: The mediatory roles of burnout syndrome and job satisfaction. Heliyon, 9(7), e17937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J., Pfeffer, J., & Zenios, S. A. (2016). The relationship between workplace stressors and mortality and health costs in the United States. Management Science, 62(2), 608–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L., Ben-Zion, I., Fear, N. T., Hotopf, M., Stansfeld, S. A., & Wessely, S. (2013). Are reports of psychological stress higher in occupational studies? A systematic review across occupational and population based studies. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e78693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebles, M., Trincado-Munoz, F., & Ortega, K. (2021). Stress and turnover intentions within healthcare teams: The mediating role of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of COVID-19 worry and supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 758438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H., Pei, Y., Yang, Y., Lu, L., Yan, W., Gao, X., & Wang, W. (2021). Factors associated with turnover intention among healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 4953–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y., Zhang, H., Qin, Z., Zou, Y., Feng, Z., & Cheng, J. (2023). The impact of meaning in life and professional happiness on the turnover intention of health care workers: A cross-sectional study from China. Human Resources for Health, 21(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Zhang, M., He, C., Wang, F., Liu, Y., Wu, J., Luo, Q., Chen, N., & Tang, Y. (2024). Characteristics and trends of workplace violence towards frontline health workers under comprehensive interventions in a Chinese Infectious Disease Hospital. Healthcare, 12(19), 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Zhang, M., Wang, F., Tang, Y., He, C., Fang, X., & Wang, X. (2025). COPSOQ III in China: Preliminary Validation of an International Instrument to Measure Psychosocial Work Factors. Healthcare, 13(7), 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. (2014). Psychosocial risks and work-related stress. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/psychosocial-risks-and-work-related-stress (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- International Labour Organization. (2016). Workplace stress: A collective challenge. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/workplace-stress-collective-challenge (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- International Labour Organization. (2022). Psychosocial risks and stress at work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/psychosocial-risks-and-stress-work (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Kelloway, E. K., Dimoff, J. K., & Gilbert, S. (2023). Mental health in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, M., Kozak, A., Wendeler, D., Paderow, L., Nübling, M., & Nienhaus, A. (2014). Psychological stress and strain on employees in dialysis facilities: A cross-sectional study with the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 9(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikunaga, K., Nakata, A., Kuwamura, M., Odagami, K., Mafune, K., Ando, H., Muramatsu, K., Tateishi, S., Fujino, Y., & CORoNa Work Project. (2023). Psychological distress, Japanese teleworkers, and supervisor support during COVID-19. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(2), e68–e73. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, T. S., Hannerz, H., Høgh, A., & Borg, V. (2005). The copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire—A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 31(6), 438–449. [Google Scholar]

- Leka, S., & Jain, A. (2010). Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: An overview. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44428 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Li, S., Li, L., Zhu, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhao, L., Li, L., & Yang, Y. (2016). Comparison of characteristics of anxiety sensitivity across career stages and its relationship with nursing stress among female nurses in Hunan, China. BMJ Open, 6(5), e010829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z., & Hong, L. (2023). Work–family conflict and mental health among Chinese female healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating effects of resilience. Healthcare, 11(12), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L., Kao, S.-F., Siu, O.-L., & Lu, C.-Q. (2011). Work stress, Chinese work values, and work well-being in the Greater China. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(6), 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W., & Wang, H. (2020). The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, N., & Zhu, B. (2018). Turnover intention of primary health workers in China: A systematic review. The Lancet, 392, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVicar, A. (2003). Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(6), 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, S. E. (2014). The web of silence: A qualitative case study of early intervention and support for healthcare workers with mental ill-health. BMC Public Health, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikunlaakso, R., Reuna, K., Selander, K., Oksanen, T., & Laitinen, J. (2022). Synergistic interaction between job stressors and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübling, M., Vomstein, M., Schmidt, S. G., Gregersen, S., Dulon, M., & Nienhaus, A. (2010). Psychosocial work load and stress in the geriatric care. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, R., Lau, Y.-S., Bower, P., Checkland, K., Rubery, J., Sutton, M., Giles, S. J., Esmail, A., Spooner, S., & Kontopantelis, E. (2021). Rates of turnover among general practitioners: A retrospective study of all English general practices between 2007 and 2019. BMJ Open, 11(8), e049827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L., Chen, X., Peng, S., Zheng, F., Tan, X., & Duan, R. (2020). Job burnout and turnover intention among Chinese primary healthcare staff: The mediating effect of satisfaction. BMJ Open, 10(10), e036702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugulies, R., Aust, B., Greiner, B. A., Arensman, E., Kawakami, N., LaMontagne, A. D., & Madsen, I. E. H. (2023). Work-related causes of mental health conditions and interventions for their improvement in workplaces. The Lancet, 402(10410), 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruotsalainen, J. H., Verbeek, J. H., Mariné, A., & Serra, C. (2015). Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(4), CD002892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T. D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Dyrbye, L. N., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C. P., Sloan, J., & Oreskovich, M. R. (2012). Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(18), 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, S., Leask, E., Patel, R., Datyner, M., Loh, E., & Braithwaite, J. (2024). Healthcare leaders navigating complexity: A scoping review of key trends in future roles and competencies. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, M. (2010). A concept analysis of turnover intention: Implications for nursing management. Collegian, 17(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevis, S. E., Patel, H., Singh, S., Ehrenfeucht, C., Little, C., Kutner, J., & Persoff, J. (2022). Impact of a physician clinical support supervisor in supporting patients and families, staff, and the health-care system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 16(1), 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y., Li, D., & Wang, H.-J. (2021). COVID-19-induced layoff, survivors’ COVID-19-related stress and performance in hospitality industry: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A., Nübling, M., Hammer, A., Manser, T., & Rieger, M. A., on behalf of the WorkSafeMed Consortium. (2020). Comparing perceived psychosocial working conditions of nurses and physicians in two university hospitals in Germany with other German professionals—Feasibility of scale conversion between two versions of the German Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ). Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 15(1), 26. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, B. M., & Kabat-Farr, D. (2022). Investigating the implications of changes in supervisor and organizational support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(6), 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Mental health at work. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2022a). Mental health at work: Policy brief. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057944 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2022b). WHO guidelines on mental health at work. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Yang, X., Kong, X., Qian, M., Zhang, X., Li, L., Gao, S., Ning, L., & Yu, X. (2024). The effect of work-family conflict on employee well-being among physicians: The mediating role of job satisfaction and work engagement. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., Kaiser, M., Nie, P., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2019). Why are Chinese workers so unhappy? A comparative cross-national analysis of job satisfaction, job expectations, and job attributes. PLoS ONE, 14(9), e0222715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 1054) | Senior Manager/ Hospital Manager (n = 23) | Department Manager (n = 115) | Department Staff (n = 795) | Intern/ Trainee/Student (n = 121) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 780 (74.00) | 9 (39.13) | 72 (62.61) | 624 (78.49) | 75 (61.98) |

| Male | 274 (26.00) | 14 (60.87) | 43 (37.39) | 171 (21.51) | 46 (38.02) | |

| Age | <25 | 211 (20.02) | 2 (8.70) | 23 (20.00) | 185 (23.27) | 1 (0.83) |

| 25~ | 415 (39.37) | 6 (26.09) | 52 (45.22) | 343 (43.14) | 14 (11.57) | |

| 35~ | 291 (27.61) | 7 (30.43) | 26 (22.61) | 200 (25.16) | 58 (47.93) | |

| 45~ | 113 (10.72) | 7 (30.43) | 13 (11.30) | 58 (7.30) | 35 (28.93) | |

| 55~ | 24 (2.28) | 1 (4.35) | 1 (0.87) | 9 (1.13) | 13 (10.74) | |

| Education | High school and below | 58 (5.50) | 3 (13.04) | 4 (3.48) | 36 (4.53) | 15 (12.40) |

| Junior college | 264 (25.05) | 2 (8.70) | 18 (15.65) | 205 (25.79) | 39 (32.23) | |

| Undergraduate | 676 (64.14) | 12 (52.17) | 74 (64.35) | 526 (66.16) | 64 (52.89) | |

| Postgraduate | 56 (5.31) | 6 (26.09) | 19 (16.52) | 28 (3.52) | 3 (2.48) | |

| Occupation | Doctor | 252 (23.91) | 9 (39.13) | 36 (31.30) | 181 (22.77) | 26 (21.49) |

| Nurse | 500 (47.44) | 6 (26.09) | 34 (29.57) | 428 (53.84) | 32 (26.45) | |

| Technical support | 125 (11.86) | 1 (4.35) | 13 (11.30) | 92 (11.57) | 19 (15.70) | |

| Administrative staff | 177 (16.79) | 7 (30.43) | 32 (27.83) | 94 (11.82) | 44 (36.36) | |

| Job title | Senior professional | 165 (15.65) | 11 (47.83) | 51 (44.35) | 99 (12.45) | 4 (3.31) |

| Intermediate professional | 340 (32.26) | 6 (26.09) | 39 (33.91) | 288 (36.23) | 7 (5.79) | |

| Junior professional | 440 (41.75) | 6 (26.09) | 20 (17.39) | 365 (45.91) | 49 (40.50) | |

| None/assistant | 109 (10.34) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (4.35) | 43 (5.41) | 61 (50.41) | |

| Working years | <1 | 146 (13.85) | 5 (21.74) | 5 (4.35) | 35 (4.40) | 101 (83.47) |

| 1~ | 236 (22.39) | 4 (17.39) | 15 (13.04) | 203 (25.53) | 14 (11.57) | |

| 6~ | 253 (24.00) | 2 (8.70) | 16 (13.91) | 233 (29.31) | 2 (1.65) | |

| 11~ | 184 (17.46) | 5 (21.74) | 32 (27.83) | 144 (18.11) | 3 (2.48) | |

| 15~ | 235 (22.30) | 7 (30.43) | 47 (40.87) | 180 (22.64) | 1 (0.83) | |

| Night work | Yes | 620 (58.82) | 6 (26.09) | 40 (34.78) | 522 (65.66) | 52 (42.98) |

| No | 434 (41.18) | 17 (73.91) | 75 (65.22) | 273 (34.34) | 69 (57.02) | |

| Shift work | Yes | 761 (72.20) | 10 (43.48) | 53 (46.09) | 616 (77.48) | 82 (67.77) |

| No | 293 (27.80) | 13 (56.52) | 62 (53.91) | 179 (22.52) | 39 (32.23) |

| Domain | Dimension | Abbreviation | Mean (Chinese Workers) | 95% CIs | Mean (International Workers a) | Difference (Chinese vs. International) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at work | Quantitative demands | QD | 37.02 | 35.94−38.09 | 39.00 | −1.98 |

| Work pace | WP | 58.54 | 57.22−59.86 | 61.00 | −2.46 | |

| Emotional demands | ED | 43.52 | 42.36−44.67 | 47.00 | −3.48 | |

| Demands for hiding emotions | HE | 54.12 | 52.92−55.32 | 57.00 | −2.88 | |

| Work organization and job contents | Influence at work | IN | 45.42 | 44.39−46.45 | 42.00 | 3.42 |

| Possibilities for development | PD | 62.27 | 61.11−63.43 | 66.00 | −3.73 | |

| Control over working time | CT | 35.57 | 34.49−36.66 | 39.00 | −3.43 | |

| Meaning of work | MW | 72.02 | 70.70−73.34 | 72.00 | 0.02 | |

| Interpersonal relations and leadership | Predictability | PR | 57.70 | 56.43−58.97 | 56.00 | 1.70 |

| Recognition | RE | 65.18 | 63.78−66.58 | 55.00 | 10.18 ** | |

| Role clarity | CL | 69.34 | 68.15−70.53 | 75.00 | −5.66 * | |

| Role conflicts | CO | 47.72 | 46.55−48.89 | 45.00 | 2.72 | |

| Illegitimate tasks | IT | 45.87 | 44.47−47.28 | 43.00 | 2.87 | |

| Quality of leadership | QL | 57.47 | 56.23−58.71 | 61.00 | −3.53 | |

| Social support from supervisor | SS | 60.09 | 58.76−61.42 | 68.00 | −7.91 * | |

| Social support from colleagues | SC | 63.08 | 61.82−64.34 | 69.00 | −5.92 * | |

| Sense of community at work | SW | 66.46 | 65.21−67.71 | 77.00 | −10.54 ** | |

| Work–individual interface | Job insecurity | JI | 46.10 | 44.70−47.50 | 39.00 | 7.10 * |

| Insecurity over working conditions | IW | 52.54 | 51.22−53.86 | 41.00 | 11.54 ** | |

| Quality of work | QW | 65.06 | 63.83−66.30 | 71.00 | −5.94 * | |

| Job satisfaction | JS | 61.79 | 60.74−62.84 | 56.00 | 5.79 * | |

| Work-life conflict | WF | 43.26 | 41.96−44.56 | 42.00 | 1.26 | |

| Social capital | Horizontal trust | TE | 64.16 | 62.84−65.48 | 62.00 | 2.16 |

| Vertical trust | TM | 62.39 | 61.23−63.55 | 64.00 | −1.61 | |

| Organizational justice | JU | 61.23 | 60.06−62.41 | 57.00 | 4.23 | |

| Health and well-being | Self-rated health | GH | 59.70 | 58.02−61.38 | 63.00 | −3.30 |

| Domain | Dimension | Senior Hospital Manager (Mean ± SD) | Department Manager (Mean ± SD) | Department Staff (Mean ± SD) | Intern/ Trainee/Student (Mean ± SD) | p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at work | QD | 53.99 ± 22.17 | 46.74 ± 17.58 | 35.68 ± 19.18 | 41.18 ± 23.99 | <0.001 |

| WP | 48.37 ± 25.09 | 62.83 ± 18.40 | 59.12 ± 21.78 | 52.58 ± 23.21 | <0.001 | |

| ED | 50.00 ± 22.47 | 50.72 ± 17.47 | 41.98 ± 18.66 | 45.52 ± 21.00 | <0.001 | |

| HE | 59.78 ± 20.05 | 59.20 ± 16.01 | 53.53 ± 20.32 | 52.07 ± 19.04 | 0.009 | |

| subtotal | 53.03 ± 17.95 | 54.87 ± 11.85 | 47.58 ± 15.50 | 47.84 ± 18.13 | <0.001 | |

| Work organization and job contents | IN | 56.25 ± 16.64 | 53.26 ± 14.91 | 43.73 ± 16.45 | 46.95 ± 19.86 | <0.001 |

| PD | 63.04 ± 22.45 | 67.61 ± 18.79 | 61.70 ± 18.76 | 60.81 ± 21.13 | 0.016 | |

| CT | 51.36 ± 17.37 | 37.93 ± 15.85 | 33.66 ± 17.30 | 42.87 ± 20.31 | <0.001 | |

| MW | 72.28 ± 20.63 | 72.28 ± 23.40 | 73.49 ± 20.63 | 62.09 ± 25.51 | <0.001 | |

| subtotal | 60.73 ± 15.34 | 57.77 ± 12.22 | 53.15 ± 12.01 | 53.18 ± 15.97 | <0.001 | |

| Interpersonal relations and leadership | PR | 60.87 ± 22.39 | 61.85 ± 18.94 | 56.82 ± 21.11 | 58.88 ± 21.86 | 0.080 |

| RE | 66.30 ± 27.81 | 66.09 ± 23.69 | 65.72 ± 22.51 | 60.54 ± 25.36 | 0.136 | |

| CL | 69.20 ± 21.82 | 72.39 ± 18.91 | 69.96 ± 19.23 | 62.40 ± 21.28 | <0.001 | |

| CO | 55.98 ± 18.80 | 48.48 ± 17.92 | 46.54 ± 19.40 | 53.20 ± 19.40 | 0.001 | |

| IT | 57.61 ± 27.63 | 44.35 ± 20.43 | 44.87 ± 23.33 | 51.65 ± 23.44 | 0.002 | |

| QL | 55.44 ± 25.20 | 62.90 ± 19.72 | 56.55 ± 20.33 | 58.75 ± 21.11 | 0.016 | |

| SS | 56.52 ± 27.40 | 61.41 ± 22.00 | 60.33 ± 22.25 | 57.95 ± 19.30 | 0.522 | |

| SC | 55.43 ± 25.51 | 63.70 ± 21.20 | 64.04 ± 20.32 | 57.64 ± 22.03 | 0.004 | |

| SW | 55.43 ± 27.91 | 64.24 ± 24.33 | 67.99 ± 19.54 | 60.64 ± 21.08 | <0.001 | |

| subtotal | 59.20 ± 18.05 | 60.60 ± 13.19 | 59.20 ± 12.35 | 57.96 ± 14.75 | 0.480 | |

| Work–individual interface | JI | 44.57 ± 26.87 | 39.13 ± 23.91 | 45.77 ± 23.01 | 55.17 ± 20.52 | <0.001 |

| IW | 43.84 ± 21.65 | 50.87 ± 18.65 | 52.38 ± 22.49 | 56.82 ± 19.81 | 0.029 | |

| QW | 48.91 ± 30.60 | 66.30 ± 20.95 | 66.23 ± 19.82 | 59.30 ± 19.40 | <0.001 | |

| JS | 53.99 ± 20.55 | 64.71 ± 16.46 | 62.00 ± 17.28 | 59.09 ± 17.71 | 0.012 | |

| WF | 52.72 ± 17.66 | 50.11 ± 20.45 | 41.48 ± 21.67 | 46.69 ± 20.01 | <0.001 | |

| subtotal | 48.80 ± 15.50 | 54.22 ± 10.78 | 53.57 ± 11.03 | 55.41 ± 12.27 | 0.059 | |

| Social capital | TE | 56.52 ± 30.36 | 63.26 ± 21.79 | 64.78 ± 21.84 | 62.40 ± 19.93 | 0.219 |

| TM | 55.07 ± 21.43 | 63.84 ± 18.20 | 62.62 ± 19.30 | 60.88 ± 19.21 | 0.184 | |

| JU | 53.26 ± 22.99 | 65.22 ± 19.01 | 60.79 ± 19.59 | 61.88 ± 17.44 | 0.026 | |

| subtotal | 54.95 ± 21.97 | 64.11 ± 17.86 | 62.73 ± 17.62 | 61.72 ± 15.80 | 0.136 |

| Variable | Total | Senior Manager/ Hospital Manager | Department Manager | Department Staff | Intern/ Trainee/Student | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleeping Troubles | 38.15 ± 22.00 | 53.26 ± 24.92 | 37.28 ± 20.43 | 38.36 ± 22.14 | 34.66 ± 20.87 | 0.003 ** |

| Burnout | 37.14 ± 20.84 | 45.92 ± 23.43 | 39.73 ± 19.65 | 36.48 ± 21.00 | 37.40 ± 20.03 | 0.083 |

| Stress | 36.33 ± 20.17 | 51.09 ± 23.88 | 39.93 ± 19.54 | 35.45 ± 20.00 | 35.88 ± 19.95 | 0.001 *** |

| Depressive Symptoms | 28.59 ± 20.48 | 37.77 ± 26.62 | 31.36 ± 18.45 | 27.78 ± 20.08 | 29.55 ± 23.03 | 0.041 * |

| General health | 59.70 ± 27.82 | 57.61 ± 37.26 | 60.22 ± 29.04 | 58.65 ± 27.23 | 66.53 ± 27.87 | 0.035 * |

| Turnover Intention 1 | 116 (11.01%) | 6 (0.57%) | 15 (1.42%) | 71 (6.74%) | 24 (2.28%) | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, C.; Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mental Health and Turnover Intention Among Health Workers at Different Occupational Statuses: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in China. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050073

Wang F, Zhang M, Huang Y, Tang Y, He C, Fang X, Wang X, Zhang Y. Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mental Health and Turnover Intention Among Health Workers at Different Occupational Statuses: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in China. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050073

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fuyuan, Min Zhang, Yiming Huang, Yuting Tang, Chuning He, Xinxin Fang, Xuechun Wang, and Yiran Zhang. 2025. "Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mental Health and Turnover Intention Among Health Workers at Different Occupational Statuses: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in China" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050073

APA StyleWang, F., Zhang, M., Huang, Y., Tang, Y., He, C., Fang, X., Wang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mental Health and Turnover Intention Among Health Workers at Different Occupational Statuses: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study in China. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050073