1. Introduction

Perfectionism has become increasingly prominent in contemporary higher education, particularly among university students facing elevated academic and social expectations. It is characterized by excessively high performance standards, overly critical self-evaluations, and heightened concern over mistakes (

Frost et al., 1990;

Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, perfectionism includes self-oriented, socially prescribed, and other-oriented forms, each associated with distinct psychological risks (

Hewitt et al., 2017). Self-oriented perfectionism reflects an internal drive for excellence, whereas socially prescribed perfectionism, where individuals perceive external pressure to meet unrealistic standards, has been consistently linked to adverse outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (

Limburg et al., 2017;

Smith et al., 2018).

Over recent decades, evidence indicates a global increase in perfectionism, particularly among younger generations, driven by rising societal pressures, neoliberal performance values, and intensifying parental expectations (

Curran & Hill, 2019,

2022). Within universities, competitive and performance-driven environments may further amplify perfectionism, as students face demanding workloads, rigorous assessment criteria, and uncertain career trajectories (

Beiter et al., 2015). Italian university students exhibit perfectionistic profiles similar to their international peers, with strong links to psychological distress, maladaptive coping, and reduced academic satisfaction (

Nosè et al., 2025;

Loscalzo et al., 2019;

Gambolò et al., 2025).

Although perfectionism is associated with disengagement, procrastination, and emotional exhaustion, it remains a complex and insufficiently understood phenomenon (

Al-Garni et al., 2025). Recent research has underscored the need to examine both its manifestations and antecedents, particularly in relation to perceived academic stress and understudied protective factors (

Fernández-García et al., 2023;

Piredda et al., 2025).

Spiritual well-being has emerged as a significant existential resource that enhances emotional balance, resilience and life satisfaction, while protecting against stress, anxiety, and depression (

Leung & Pong, 2021;

Okan et al., 2025;

Rudolph & Barnard, 2023). Unlike religiosity, which centers on formal belief systems and rituals, spiritual well-being encompasses a broader sense of meaning and purpose derived from personal, relational, and transcendent connections, including engagement with art and music (

Al-Thani, 2025;

Ryff, 2021).

Although the relationship between spiritual well-being and perfectionism remains underexplored, related constructs such as self-compassion have been shown to buffer maladaptive effects, with higher levels linked to reduced depressive symptoms and psychological distress, even among self-critical perfectionists (

Kawamoto et al., 2023;

Tobin & Dunkley, 2021). In academic contexts, self-compassion moderates the relationship between perfectionistic striving and mental health, reducing stress and promoting well-being (

With et al., 2024). Similarly, belonging to religious communities may mitigate the negative impact of socially prescribed perfectionism (

Lin & Wang, 2024).

Broader evidence suggests that spirituality fosters life satisfaction, resilience, and lower anxiety, although causal mechanisms remain unclear (

Benedetto et al., 2024;

Rudolph & Barnard, 2023). A strong spiritual foundation may counterbalance perfectionistic tendencies by promoting intrinsic self-worth, self-compassion, and greater life satisfaction (

Deb et al., 2020;

Mathad et al., 2019), whereas low spiritual well-being may increase reliance on external validation, heightening vulnerability to maladaptive perfectionism (

Negi et al., 2021). Moreover, the relational and transcendent aspects of spirituality may alleviate the interpersonal stressors inherent in socially prescribed perfectionism by fostering a broader perspective on human value and interconnectedness (

Fisher et al., 2000).

Several studies have investigated perfectionism in Italian populations, including adolescents, young adults, and university students. For example,

Di Fabio et al. (

2019) explored its relationship with humor among university students, while

Piredda et al. (

2025) developed and validated the Perfectionism Inventory to assess perfectionism and academic stress. Other studies have linked perfectionism to eating behaviors (

Vacca et al., 2021), procrastination and narcissistic vulnerability (

Sommantico et al., 2024), and occupational outcomes such as work engagement and workaholism (

Spagnoli et al., 2021).

Despite increasing attention to perfectionism among university students, the role of spiritual well-being remains largely unexplored. Previous studies have focused on related constructs such as self-compassion or religiosity, but few studies have examined how spiritual well-being may buffer or intensify perfectionistic tendencies. This gap is especially relevant in the Italian context, where spirituality blends cultural, personal, and religious dimensions that may shape students’ psychological functioning.

The present study investigates associations between spiritual well-being and multidimensional perfectionism in a large national sample of Italian university students. We hypothesized that (H1) higher spiritual well-being would relate negatively to maladaptive perfectionism and (H2) positively to adaptive perfectionism; and that (H3, exploratory) gender and age differences would emerge, with women and younger students reporting higher perfectionism.

3. Results

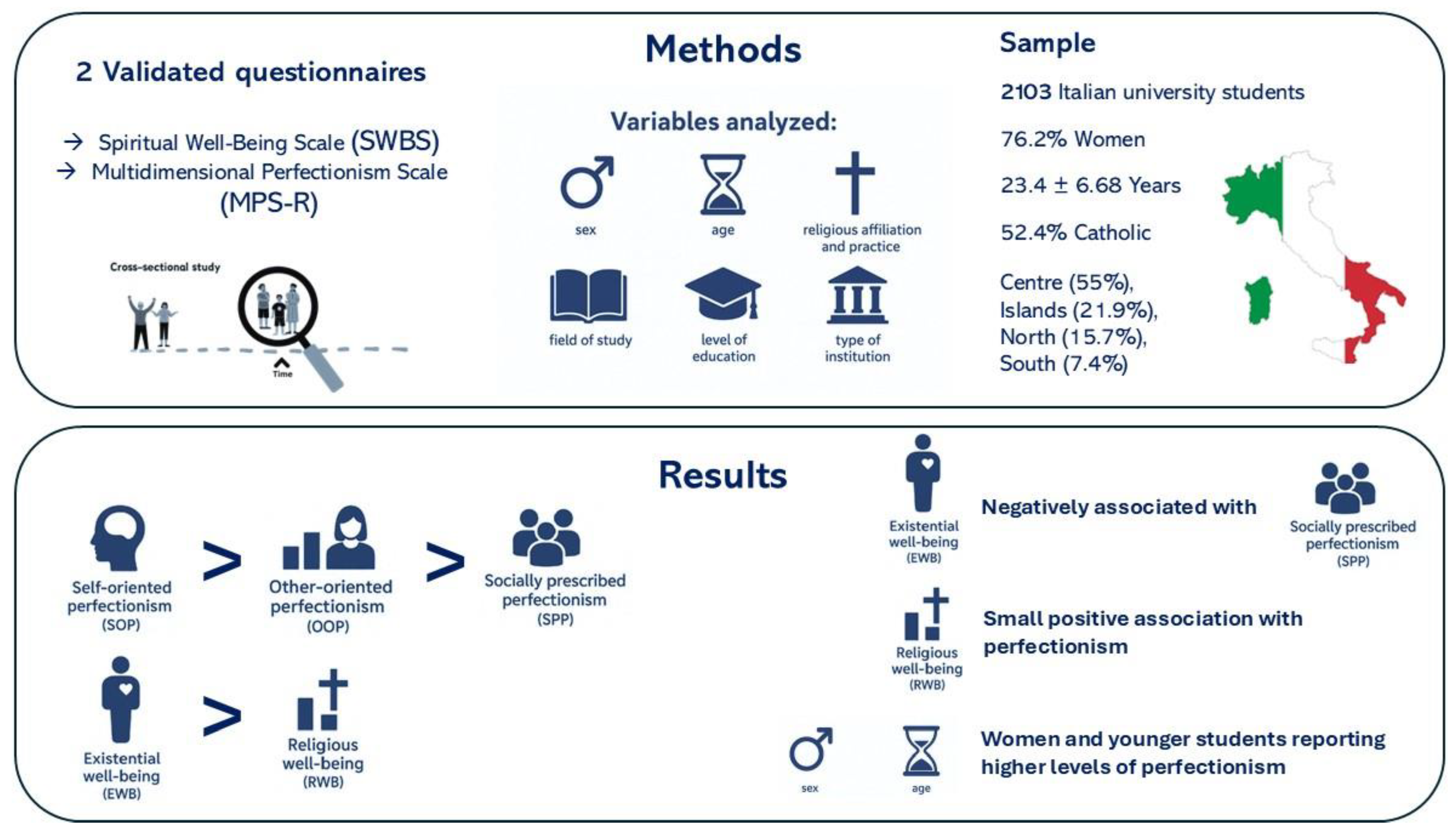

3.1. Sample Description

Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, which comprised 2103 university students. The gender distribution was notably uneven, with 76.2% identifying as females and 23.8% as males. The mean age was 23.4 years (SD = 5.68), with the majority aged 18–24 (76.46%). In terms of religious affiliation, 52.4% identified as Catholic. A combined 27.2% described themselves as Atheist or Agnostic, and 13.9% expressed indifference toward religion. Smaller portions reported affiliation with Orthodox Christianity (1.9%), other Christian denominations (1.9%), Islam (0.8%), and other faiths. Only 28.9% reported active religious practice. Regarding academic discipline, 70.2% were enrolled in health-related programs. Students in the humanities accounted for 13.1%, engineering for 8.3%, and science for 5.8%. Academic year distribution was relatively balanced, with the largest groups in the first (23.2%) and second years (41.9%). Regionally, most participants were from central Italy (55%), followed by the Islands (21.9%), and the North (15.7%). A majority attended public universities (81.6%), while 18.4% were enrolled in private institutions. Additionally, 35.8% were offsite students, and 19.4% reported receiving either a scholarship or placement in a College of Merit.

3.2. Analysis of MPS-R Responses

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for Multi-dimensional Perfectionism Scale–Revised (MPS-R) was 0.74.

Table 2a–c summarizes responses to MPS-R across its three dimensions: self-oriented (SOP), other-oriented (OOP), and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP).

Self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) was strongly endorsed, with participants reporting high personal standards, striving for excellence, and discomfort with mistakes. Items such as “I set very high standards for myself” and “It makes me uneasy to see an error in my work” received widespread agreement, indicating that self-directed perfectionism was pervasive.

Other-oriented perfectionism (OOP) showed moderate endorsement. Students held high expectations for important others, but these interpersonal standards were less prominent than their own self-directed standards.

Socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) reflected moderate perceptions of external pressures. While some students felt that others expected them to succeed, these pressures were less internalized compared to their personal standards, suggesting that external demands were acknowledged but not strongly adopted.

Table 3 PART A summarize descriptive statistics for the MPS-R items and domains. Participants showed strong self-oriented perfectionism (SOP), with the highest scores on items reflecting discomfort with mistakes and high personal standards, highlighting an internal drive for flawlessness. Other-oriented (OOP) and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) were endorsed less strongly, indicating that perfectionistic tendencies were primarily self-imposed rather than externally driven. At the domain level, SOP had the highest mean, followed by OOP and SPP, and the overall MPS-R score indicated a moderate to high prevalence of perfectionistic traits.

3.3. Analysis of Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) Responses

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.970, 0.893 and 0.937 for RWB, EWB and SWB, respectively. The results in

Table 3 PART B indicate that Italian university students report a moderate overall level of spiritual well-being (SWBS = 68.8). Within this construct, existential well-being (EWB) was notably higher than religious well-being (RWB), suggesting that participants derive greater meaning and satisfaction from internal resources than from religious beliefs or practices. Positive appraisals of life and purpose were strongly endorsed, while negative or nihilistic statements were largely rejected. In contrast, items assessing religious well-being indicated a weak personal connection with God, with low agreement on statements reflecting a meaningful relationship or perceived support from God. For further details of the comparison,

Table A1 in

Appendix A presents the results from

Table 3 also divided by sex.

3.4. Associations Between Perfectionism and Spiritual Well-Being

The correlation matrix (

Table 4) revealed distinct patterns between perfectionism dimensions (MPS-R items) and spiritual well-being variables.

Self-oriented perfectionism indicators (e.g., “It makes me uneasy to see an error in my work,” “I set very high standards for myself”) showed weak to moderate negative correlations with existential well-being items, such as life satisfaction, optimism about the future, and sense of purpose (r range ≈ −0.05 to −0.12, p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). These results suggest that higher self-imposed standards and intolerance of mistakes are associated with lower existential clarity and fulfillment.

Items reflecting socially prescribed perfectionism (e.g., “I find it difficult to meet others’ expectations of me,” “The people around me expect me to succeed at everything I do”) demonstrated the strongest negative associations with existential well-being, including life satisfaction and perceived purpose (r range ≈ −0.20 to −0.40, all p < 0.001). This indicates that perceived external demands are particularly detrimental to personal meaning and well-being.

By contrast, other-oriented perfectionism (e.g., “Everything that others do must be of top-notch quality,” “I cannot stand to see people close to me make mistakes”) showed weak positive correlations with certain religious well-being items, such as belief in God’s love or support (r ≈ 0.05 to 0.12, p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). However, these associations were smaller in magnitude compared to the negative links observed for self- and socially prescribed perfectionism.

Overall, the results highlight that perfectionism is differentially related to spiritual well-being: socially prescribed perfectionism exhibits the most consistent and detrimental correlations with existential dimensions, while self-oriented perfectionism is linked to reduced fulfillment and optimism, and other-oriented perfectionism displays only minor associations with religious beliefs.

3.5. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Between Dimensions of Perfectionism, Spiritual Well-Being and Related Socio-Demographic Factors

The linear regression model (

Table 5) examining the association between perfectionism (MPS-R) and the dimensions of spiritual well-being explained a modest proportion of the variance (R = 0.315, R

2 = 0.099, N = 2103), indicating that these predictors accounted for approximately 10% of the variance in perfectionism.

Existential Well-Being (EWB), which reflects a relatively weak effect which reflects meaning, purpose, satisfaction, and perceived direction in life without invoking religious terminology, was the strongest predictor, showing a significant negative association with perfectionism (β = −0.369, SE = 0.028, t = −13.117, p < 0.001). Religious Well-Being (RWB), which explicitly refers to a personal relationship with God and the belief that God provides care and guidance, showed a small but significant positive effect (β = 0.067, SE = 0.024, t = 2.754, p = 0.006).

Sociodemographic covariates also contributed: women reported higher perfectionism than men (β = 1.662, SE = 0.597, t = 2.785, p = 0.005), while young adults (β = −2.825, SE = 0.645, t = −4.379, p < 0.001) and middle-aged participants (β = −3.929, SE = 1.491, t = −2.635, p = 0.008) exhibited lower perfectionism than the youngest group. Other demographic variables, including religious affiliation beyond Catholicism, area or level of study, geographic location, type of institution (public vs. private), off-site residence, and scholarship status, were not significant.

4. Discussion

This survey investigated the relationship between spiritual well-being, including both religious and existential dimensions, and multidimensional perfectionism, as well as the socio-demographic and contextual factors shaping these associations. Drawing on a large sample of 2103 Italian students, the study provides insights into how spiritual well-being interacts with perfectionism in higher education.

A moderate to high prevalence of perfectionism emerged, with self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) most prominent, followed by other-oriented (OOP), and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP). This pattern underscores the predominance of an internalized drive for high standards, while external and interpersonal demands appear less influential. SOP’s prominence resonates with theoretical accounts emphasizing its dual role, as both a motivational asset and a vulnerability depending on the context (

Hewitt et al., 2017;

Hewitt & Flett, 1991;

Stoeber & Otto, 2006). The absence of negative associations between SOP and existential well-being suggests that, in this population, SOP may reflect a form of adaptive striving for excellence, characterized by intrinsic motivation and goal pursuit, rather than maladaptive perfectionism. This interpretation is consistent with emerging work distinguishing healthy striving or “excellencism” from rigid, self-critical perfectionism (

Gaudreau et al., 2022), though further research is required to substantiate this distinction. In contrast, OOP and SPP, typically linked with interpersonal conflict and psychological maladjustment (

Hewitt & Flett, 1991), were less prevalent, suggesting a relatively low level of maladaptive striving in this sample.

Overall spiritual well-being was moderate, with existential well-being (EWB) consistently outweighing religious well-being (RWB). While formal religious engagement appears limited, students reported a strong sense of meaning, purpose, and optimism. This reflects a reliance on existential meaning-making over traditional religiosity, consistent with broader European trends of secularization and the search for meaning outside traditional religious institutions among youth (

Bossi et al., 2023;

Lo Cascio et al., 2025;

Rudolph & Barnard, 2023).

Associations between spiritual well-being and perfectionism were significant but differentiated. Higher EWB was negatively related to SPP, highlighting a protective effect against maladaptive perfectionism, which is strongly linked with depression, anxiety, and suicidality (

Limburg et al., 2017;

Smith et al., 2018). These results support evidence that spirituality helps students frame striving within broader systems of meaning, mitigating risks of burnout (

Mathad et al., 2019;

With et al., 2024). RWB, by contrast, showed a small positive association with perfectionism. While the effect was weak, it may reflect that religious adherence sometimes reinforces external standards or evaluative concerns, even as it provides belonging and support. This dual role warrants further study.

Beyond these direct associations, the interplay between spirituality, perfectionism, and broader psychosocial mechanisms deserves deeper consideration. Perfectionism, particularly in its socially prescribed form, is embedded in relational and cultural contexts where external validation, competition, and performance pressures dominate. Spirituality, especially existential well-being, appears to counterbalance these dynamics by shifting the basis of self-worth from external evaluation to intrinsic meaning, belonging, and acceptance. This aligns with broader psychosocial theories that position spirituality as a resilience factor fostering social connectedness, emotional regulation, and purpose-driven coping (

McEntee et al., 2013). In this framework, spirituality not only mitigates perfectionism’s maladaptive outcomes but also situates striving within a coherent life narrative, reducing vulnerability to anxiety and burnout. Conversely, when spiritual well-being is low, students may rely more heavily on achievement and external approval as sources of identity, reinforcing perfectionistic standards and their psychosocial costs. Thus, spirituality may function as a mediating mechanism linking perfectionism with broader psychosocial outcomes such as distress, interpersonal conflict, and academic disengagement. Future studies should explicitly model these mediating pathways to clarify how spiritual resources shape the social and psychological consequences of perfectionism.

Demographic differences were also observed. Women reported higher perfectionism than men, echoing prior findings linking gendered expectations and evaluative fears to perfectionistic tendencies (

Ghosh & Roy, 2017). Younger students displayed higher levels of perfectionism compared with older peers, suggesting a developmental trend whereby perfectionistic tendencies may diminish with age as individuals gain broader life perspectives and self-acceptance. This difference may have been detected due to the large sample size, as prior studies with smaller cohorts yielded inconsistent results (

Daniilidou, 2023;

Diamantopoulou & Platsidou, 2014;

Landa & Bybee, 2007;

Robinson et al., 2021). The lack of significant differences across institutions, regions, or disciplines suggests that perfectionism and spiritual well-being and its existential correlates represent a widespread concern across the Italian university system.

These findings carry practical significance for higher education. Acknowledging the role of spiritual well-being in moderating perfectionism can inform the design of holistic student support initiatives.

First, routine screening for perfectionism and low existential well-being could be incorporated into university counseling services to identify at risk students early. Targeted support may include meaning-centered interventions, such as mindfulness, values clarification, narrative reflection, and peer-support groups. These approaches can help students reframe perfectionistic standards, cultivate self-acceptance and reduce reliance on external validation.

Second, universities can enhance campus environments that promote spiritual and existential development beyond formal religious practice. Opportunities such as service learning, volunteerism, intercultural dialogue, arts engagement arts, and access to natural spaces can strengthen belonging, purpose, and resilience. Multi-faith or chaplaincy services can also provide safe spaces for students to explore existential concerns and cultivate meaning in inclusive ways (

Barton et al., 2020). For students who identify with a religious tradition, spiritual guidance may further reinforce self-worth and belonging. For example, the notion of a compassionate and forgiving God, central to monotheistic religions such as Christianity in the Italian context, can offer a counterbalance to the fear of failure and excessive reliance on external validation, thereby supporting more adaptive forms of striving (

Duffield et al., 2024;

Saliba, 2025).

Third, academic staff play a crucial role in shaping how perfectionism is experienced. Faculty training programs should equip educators to recognize perfectionistic tendencies and adopt pedagogical approaches that balance high standards with psychological safety. Evidence-based practices include formative assessments that emphasize progress over flawless performance, timely and constructive feedback, and explicit normalization of mistakes as part of learning (

Brookhart, 2011;

Fried, 2011). Such approaches can help mitigate performance pressure while maintaining motivation for excellence.

Finally, structural measures at the institutional level are needed. Universities should expand counseling services, develop psychoeducational workshops on perfectionism, and launch awareness campaigns to normalize help-seeking and challenge performance-driven cultures. Evidence supports the effectiveness of brief cognitive-behavioral programs and resilience-building workshops in reducing maladaptive perfectionism (

Arana et al., 2017). Adapting these approaches for university settings can help reframe perfectionism not merely as an individual issue but as a systemic challenge within academic culture. By embedding meaning-centered practices within both counseling and teaching structures, universities can promote achievement while protecting student well-being.

Future research should pursue longitudinal and qualitative approaches to clarify causal mechanisms and subjective experiences. Comparative studies across cultural contexts would also illuminate whether the observed patterns reflect universal trends or specific features of Italian higher education. Moreover, differentiating between adaptive striving and maladaptive perfectionism in relation to existential well-being could refine our understanding of protective versus risk pathways.

Strengths and Limitations

This nationwide survey, the largest to date on spiritual well-being and perfectionism in Italian universities, included over 2100 students across regions and disciplines. Its strengths lie in sample diversity, the use of validated instruments, and adherence to STROBE guidelines, all of which enhance reliability and validity.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference. While higher existential well-being may reduce maladaptive perfectionism, it is equally possible that perfectionistic tendencies influence spiritual resources. Longitudinal research is needed to clarify directionality. Second, reliance on self-report introduces potential bias, including social desirability and distorted self-perceptions, particularly concerning sensitive constructs such as spirituality. Third, despite the nationwide scope, the sample composition was not fully representative: women and younger students were overrepresented, and a substantial proportion of respondents were enrolled in health-related programs. Although this gender and age distribution reflects national university demographics (

AlmaLaurea, 2024), the imbalance limits the generalizability of findings, as perfectionism and spiritual well-being may vary across genders, age groups, and academic fields. Future studies should employ targeted recruitment strategies to ensure more balanced representation. Finally, the use of online recruitment may have attracted students already interested in perfectionism or spirituality. Randomized or stratified sampling approaches would enhance representativeness in future research.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that existential well-being is a protective factor against socially prescribed perfectionism among university students. While perfectionism is deeply embedded in academic culture, fostering meaning, purpose, and intrinsic self-worth may help students navigate pressures without succumbing to maladaptive outcomes.

For universities, the findings translate into several actionable recommendations. Institutions should integrate meaning-centered approaches into counseling and student support services, expand co-curricular opportunities for existential and spiritual development, and promote learning environments where mistakes are normalized as integral to growth. Faculty development initiatives should prepare educators to recognize and address perfectionism, while systemic interventions—such as workshops, awareness campaigns, and resilience training—can reduce stigma, enhance coping resources, and promote psychological safety. Universities should also recognize the role of chaplaincy and multi-faith services in supporting students’ spiritual well-being. In contexts where monotheistic traditions are prominent, faith-based perspectives emphasizing compassion, forgiveness, and unconditional worth may provide additional resources to counteract maladaptive perfectionism and reinforce belonging and resilience

By addressing perfectionism as both an individual and cultural issue, universities can create inclusive and sustainable learning environments that support academic excellence alongside mental health. These findings underscore the value of integrating existential and spiritual perspectives into student well-being initiatives, with potential long-term benefits for both academic adjustment and overall psychological resilience.