The Development of Quality Indicators to Assess Family Wellbeing Outcomes Following Engagement with Children’s Mental Health Services in Ontario, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family Functioning and Parenting

1.2. Distress of Parents

1.3. Parental Supports

1.4. Quality Indicators

1.5. Purpose of Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. QI Calculation and Risk Adjustment Process

2.2. Sample

2.3. Outcome/Dependant Variable

2.4. Stratification for Direct Adjustment

2.5. Covariate Risk Adjustors

- Related to the child or youth (8 measures): sex, age, any of 4 traumas (sexually abused or assaulted, verbally abused or assaulted, emotionally abused, or having witnessed domestic violence), consideration of self-injury, being disruptive or showing poor productivity at school, high externalizing behaviours (based on stealing, elopement, bullying peers, preoccupation with violence, violence to others, intimidation of others, violent ideation, impulsivity, physically abusive behaviour, outbursts of anger, defiant behaviour, and argumentativeness), worsening of psychiatric symptoms, and inadequate problem solving;

- Related to parents or the family (4 measures): unavailable unpaid support (based on five domains of need: crisis situations, financial problems, babysitting, emotional support, and respite), a parent has developmental or mental health issues, a parent or primary caregiver has experienced a major life stressor, and caregiver anger, depression, or distress (not applied to the caregiver distress QIs);

- Related to the provider or system (2 measures): inpatient status, and 6 or more months between the baseline and follow-up assessments.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Notable Child/Youth Level Covariates

4.2. Notable Parent/System-Level Covariates

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Opportunities for Quality Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ChYMH | Child and Youth Mental Health Assessment |

| ChYMH-DD | Child and Youth Mental Health Assessment (Developmental Disabilities) |

| QI | Quality Indicator |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

Appendix A

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behaviour. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(4), 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, N., Ye, S., Page, A. C., Trickey, D., Lyttle, M. D., Hiller, R. M., & Halligan, S. L. (2023). A systematic literature review of the relationship between parenting responses and child post-traumatic stress symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2156053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almas, A. N., Grusec, J. E., & Tackett, J. L. (2011). Children’s disclosure and secrecy: Links to maternal parenting characteristics and children’s coping skills. Social Development, 20(3), 624–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Subiela, X., Castellano-Tejedor, C., Villar-Cabeza, F., Vila-Grifoll, M., & Palao-Vidal, D. (2022). Family factors related to suicidal behavior in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrock, S. M., & Weitzman, M. (2014). Parental psychological distress and children’s mental health: Results of a national survey. Academic Pediatrics, 14(4), 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, L. G., Anthony, B. J., Glanville, D. N., Naiman, D. Q., Waanders, C., & Shaffer, S. (2005). The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auditor General of Ontario. (2025). Performance audit: Community-based child and youth mental health program. Available online: https://auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en25/pa_CYMH_en25.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Bahmani, T., Naseri, N. S., & Fariborzi, E. (2023). Relation of parenting child abuse based on attachment styles, parenting styles, and parental addictions. Current Psychology, 42(15), 12409–12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, K., Lee, S., De Los Reyes, T., Lo, L., Cleverley, K., Pidduck, J., Mahood, Q., Gorter, J. W., & Toulany, A. (2022). Quality indicators for youth transitioning to adult care: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2021055033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative Parenting Revisited: History and Current Status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (1st ed., pp. 11–34). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K., Mor, V., Morris, J., Murphy, K. M., Moore, T., & Harris, Y. (2002). Identification and evaluation of existing nursing homes quality indicators. Health Care Financing Review, 23(4), 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berla, N., Peisch, V., Thacher, A., Pearlstein, J., Dowdle, C., Geraghty, S., & Cosgrove, V. (2022). All in the family: How parental criticism impacts depressive symptoms in youth. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S., Moghaddam, N., & Tickle, A. (2015). What are the factors that influence parental stress when caring for a child with an intellectual disability? A critical literature review. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 61(3), 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, C. F., Worsley, D., Pettit, A. R., & Doupnik, S. K. (2022). Caregiver experiences during their child’s acute medical hospitalization for a mental health crisis. Journal of Child Health Care, 26(1), 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2013). CCRS Quality indicators risk adjustment methodology. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/ccrs_qi_risk_adj_meth_2013_en_0.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Chng, G. S., Wild, E., Hollmann, J., & Otterpohl, N. (2014). Children’s evaluative skills in informal reasoning: The role of parenting practices and communication patterns. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 3(2), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, A. I., Fanti, K., Mavrommatis, I., Soursou, G., Pergantis, P., & Drigas, A. (2025). Social affiliation and attention to angry faces in children: Evidence for the contributing role of parental sensory processing sensitivity. Children, 12(4), 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J. E., Deneault, A., Devereux, C., Eirich, R., Fearon, R. M. P., & Madigan, S. (2022). Parental sensitivity and child behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. Child Development, 93(5), 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, C., Violato, M., Fairbanks, H., White, E., Parkinson, M., Abitabile, G., Leidi, A., & Cooper, P. J. (2017). Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of brief guided parent-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and solution-focused brief therapy for treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(7), 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnic, K., & Ross, E. (2017). Parenting stress and parental efficacy. In K. Deater-Deckard, & R. Panneton (Eds.), Parental stress and early child development. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, A., Runge-Ranzinger, S., Banaschewski, T., Horstick, O., Elwishahy, A., Olarte-Peña, M., Faber, C., Müller, T., Brugnara, L., Thom, J., Mauz, E., & Peitz, D. (2024). Mental health indicators for children and adolescents in OECD countries: A scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1303133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquenne Godfrey, G., Downes, N., & Cappe, E. (2024). A systematic review of family functioning in families of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 54(3), 1036–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. (1983). Quality assessment and monitoring: Retrospect and prospect. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 6(3), 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. (1985). Twenty years of research on the quality of medical care: 1964–1984. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 8(3), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. (2005). Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44(3), 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, C., & Crummy, A. (2022). The impact of childhood trauma on children’s wellbeing and adult behavior. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(1), 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L., Boyle, M. H., Abelson, J., & Waddell, C. (2018). Measuring children’s mental health in Ontario: Policy issues and prospects for change. Journal of the Canadian Acadamey of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(2), 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, C. J. (2023). A meta-analysis of informal and formal family social support studies: Relationships with parent and family psychological health and well-being. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 16(2), 514–529. [Google Scholar]

- Ettorchi-Tardy, A., Levif, M., & Michel, P. (2012). Benchmarking: A method for continuous quality improvement in health. Healthcare Policy|Politiques de Santé, 7(4), E101–E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Luo, J., Boele, M., Windhorst, D., Van Grieken, A., & Raat, H. (2024). Parent, child, and situational factors associated with parenting stress: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(6), 1687–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M. A., & Aunos, M. (2020). Recent trends and future directions in research regarding parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 7(3), 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alonso, R., Álvarez-Díaz, M., Woitschach, P., Suárez-Álvarez, J., & Cuesta, M. (2017). Parental involvement and academic performance: Less control and more communication. Psicothema, 4(29), 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrey, A. E., Hughes, N. D., Simkin, S., Locock, L., Stewart, A., Kapur, N., Gunnell, D., & Hawton, K. (2016). The impact of self-harm by young people on parents and families: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 6(1), e009631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A., Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2020). Uncovering the links between parenting stress and parenting styles: The role of psychological flexibility within parenting and global psychological flexibility. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, R., Jones, D. J., & Parent, J. (2013). Behavioral parenting interventions for child disruptive behaviors and anxiety: What’s different and what’s the same. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, R. D., & McClure, J. M. (2015). Clinical practice of cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: The nuts and bolts (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant, C., & Good, D. (2023). Mental health complexity among children and youth: Current conceptualizations and future directions. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 42(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, M., Rad, D., & Stoian, C. (2024). Family functioning, parental attachment and students’ academic success. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Ma, M., Li, H., Wang, J., Liu, J., Qian, H., Zhu, P., & Xu, X. (2024). Family intimacy and adaptability and non-suicidal self-injury: A mediation analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T., Gomez-Baya, D., Trindade, J. S., Botelho Guedes, F., Cerqueira, A., & De Matos, M. G. (2022). Relationship between family functioning, parents’ psychosocial factors, and children’s well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 43(9), 2380–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, A., & Molero Jurado, M. D. M. (2022). The Moderating role of family functionality in prosocial behaviour and school climate in adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, A., Narcisse, M.-R., Hall, D. E., & Kuo, D. Z. (2014). Financial and psychological stressors associated with caring for children with disability. Families, Systems, & Health, 32(3), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouin, J., Da Estrela, C., Desmarais, K., & Barker, E. T. (2016). The impact of formal and informal support on health in the context of caregiving stress. Family Relations, 65(1), 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario. (2019). Developing and implementing a needs-based autism program. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/developing-implementing-needs-based-autism-program (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gray, D. E. (2006). Coping over time: The parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenspan, S., Harris, J. C., & Woods, G. W. (2015). Intellectual disability is “a condition, not a number”: Ethics of IQ cut-offs in psychiatry, human services and law. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 1(3), 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, E. B., Atkinson, L., Chater, A., Gahagan, A., Tran, A., & Gillison, F. B. (2022). A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of parental communication about health and health behaviours on children’s health and wellbeing. Preventive Medicine, 159, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, D. M., Williams, N., Beach, C., Buzath, E., Cohen, J., Declercq, A., Fisher, K., Fries, B. E., Goodridge, D., Hermans, K., Hirdes, J. P., Seow, H., Silveira, M., Sinnarajah, A., Stevens, S., Tanuseputro, P., Taylor, D., Vadeboncoeur, C., & Martin, T. L. W. (2022). A multi-stage process to develop quality indicators for community-based palliative care using interRAI data. PLoS ONE, 17(4), e0266569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjicharalambous, D. D., & Demetriou, D. L. (2021). Investigating the influences of parental stress on parents parenting practices. International Journal of Science Academic Research, 2(02), 1140–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, M., Brown, H. K., Chacra, M. A., Tint, A., Vigod, S., Bluestein, D., & Lunsky, Y. (2019). Mental health challenges and resilience among mothers with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 12(4), 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C. J. (2014). Parents’ employment and children’s wellbeing. The Future of Children, 24(1), 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, R. C., Rollins, C. K., & Chan, J. A. (2007). Risk-Adjusting Outcomes of Mental Health and Substance-Related Care: A Review of the Literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 15(2), 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, A., Honkaniemi, H., & Juárez, S. P. (2023). The effect of parental leave on parents’ mental health: A systematic review. The Lancet Public Health, 8(1), e57–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, A., Hustedt, J. T., Slicker, G., Hallam, R. A., & Gaviria-Loaiza, J. (2023). Linking early head start children’s social–emotional functioning with profiles of family functioning and stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 37(1), 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseworth, J., Kilaberia, T., Ticha, R., & Abery, B. (2022). Risk adjustment in home and community based services outcome measurement. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3, 830175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L., Feder, M., Abar, B., & Winsler, A. (2016). Relations between parenting stress, parenting style, and child executive functioning for children with ADHD or Autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3644–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, F., Baiocco, R., & Pistella, J. (2022). Children’s and adolescents’ happiness and family functioning: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. N., Hirdes, J. P., Poss, J. W., Kelly, M., Berg, K., Fries, B. E., & Morris, J. N. (2010). Adjustment of nursing home quality indicators. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junek, W. (2012). Government monitoring of the mental health of children in Canada: Five surveys (Part I). Journal of Canadian Academic Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kamis, C. (2021). The long-term impact of parental mental health on children’s distress trajectories in adulthood. Society and Mental Health, 11(1), 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijsers, L., & Poulin, F. (2013). Developmental changes in parent–child communication throughout adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 49(12), 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelada, L., Hasking, P., & Melvin, G. (2016). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and family functioning: Adolescent and parent perspectives. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(3), 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A. (2013). Perceived parental warmth, and children’s psychological adjustment, and personality dispositions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(2), 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, B., Hojatkhah, S. M., & Torabi-Nami, M. (2016). Family functioning, identity formation, and the ability of conflict resolution among adolescents. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(4), 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K. A., Darney, B. G., Gallo, A. M., & Angst, D. B. (2010). Parental perceptions of the outcome and meaning of normalization. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerber, M. I., Mack, J. T., Seefeld, L., Kopp, M., Weise, V., Starke, K. R., & Garthus-Niegel, S. (2023). Psychosocial work stress and parent-child bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clarifying the role of parental symptoms of depression and aggressiveness. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneman, L. M., Loeber, R., Hipwell, A. E., & Koot, H. M. (2009). Girls’ disruptive behavior and its relationship to family functioning: A review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(3), 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane-Fall, M. B., & Neuman, M. D. (2013). Outcomes measures and risk adjustment. International Anesthesiology Clinics, 51(4), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J. E. (2022). Annual Research Review: Cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(4), 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, J., Hu, Y., Huang, X., Li, Y., Li, Y., Shi, Z., Yang, R., Peng, H., Ma, S., Wan, X., & Peng, W. (2025). The association of family functioning and suicide in children and adolescents: Positive behavior recognition and non-suicidal self-injury as sequential mediators. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1505960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.-Y., Rong, J.-R., & Lee. (2013). Resilience among caregivers of children with chronic conditions: A concept analysis. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 6, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Yang, W., Xie, W., & Li, H. (2023). The integrative role of parenting styles and parental involvement in young children’s science problem-solving skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1096846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C., Washington-Nortey, P.-M., Hill, O. W., & Serpell, Z. N. (2019). Family functioning and not family structure predicts adolescents’ reasoning and math skills. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(10), 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, J. M., Yen, S., Weinstock, L. M., & Spirito, A. (2012). Adolescent and caregiver perception of family functioning: Relation to suicide ideation and attempts. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackler, J. S., Kelleher, R. T., Shanahan, L., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & O’Brien, M. (2015). Parenting stress, parental reactions, and externalizing behavior from ages 4 to 10. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(2), 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B. M., & Cobham, V. E. (2012). Family functioning in the aftermath of a natural disaster. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, A. N., & Mount, K. (2011). Parents of children with mental illness: Exploring the caregiver experience and caregiver-focused interventions. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(2), 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, J., Stoel, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Juffer, F., Koot, H. M., & Alink, L. R. A. (2009). Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalizing problems: Differential susceptibility of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(5), 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L. A., Hirdes, J., Poss, J. W., Slegers-Boyd, C., Caldarelli, H., & Martin, L. (2015). Informal caregivers of clients with neurological conditions: Profiles, patterns and risk factors for distress from a home care prevalence study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J. N., Fries, B. E., Frijters, D., Hirdes, J. P., & Steel, R. K. (2013). interRAI home care quality indicators. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerenz, D. R., Austin, J. M., Deutscher, D., Maddox, K. E. J., Nuccio, E. J., Teigland, C., Weinhandl, E., & Glance, L. G. (2021). Adjusting quality measures for social risk factors can promote equity in health care. Health Affairs, 40(4), 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, I. I., Perlman, C., Meyer, S., & Ferro, M. A. (2020). Child mental illness and mental health service use: Role of family functioning (family functioning and child mental health). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(9), 2602–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, E., Friedlander, R., & Salih, T. (2019). Falling through the cracks: How service gaps leave children with neurodevelopmental disorders and mental health difficulties without the care they need. BC Medical Journal, 6(3), 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, M., Anagnostou, E., & Ungar, W. J. (2018). Practice patterns and determinants of wait time for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in Canada. Molecular Autism, 9(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. (2017a). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. (2017b). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review, 53(7), 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, C., Burgio, S., Lavanco, G., & Alesi, M. (2021). Parental distress and perception of children’s executive functioning after the first COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego-Ojeda, M., & Rusu, P. P. (2023). Emotion regulation, parental stress and family functioning: Families of children with disabilities vs. normative families. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 139, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G., Li, B., Xu, L., Ai, S., Li, X., Lei, X., & Dou, G. (2024). Parenting style and young children’s executive function mediate the relationship between parenting stress and parenting quality in two-child families. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, A., Castro, P., Gonçalves-Pinho, M., Teixeira, J., Santos, J. V., Viana, J., Lobo, M., Santos, P., & Freitas, A. (2019). Primary health care quality indicators: An umbrella review. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e0220888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, H., Clarke, G., & Kumar, S. (2006). Exploring parents’ responses to their child’s deliberate self-harm. Health Education, 106(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan, A., Harb, A. M., Baqeas, M. H., Al.Khashashneh, O. Z., & Harb, E. (2022). The relationship of family and school environments with depression, anxiety, and stress among jordanian students: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nursing, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y., Lin, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Wu, J. Y., Hu, W., Xu, S., & You, J. (2018). The mediating role of coping strategy in the association between family functioning and nonsuicidal self-injury among Taiwanese adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(7), 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesch, S. K., Anderson, L. S., & Krueger, H. A. (2006). Parent–child communication processes: Preventing children’s health-risk behavior. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 11(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. M., & Howe, N. (2012). Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(2), 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer, N., Wilder, J., Scheja, M., & Gustavsson, A. (2020). Managing children with challenging behaviours. Parents’ meaning-making processes in relation to their children’s ADHD diagnosis. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(4), 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopnarine, J. L., Krishnakumar, A., Metindogan, A., & Evans, M. (2006). Links between parenting styles, parent–child academic interaction, parent–school interaction, and early academic skills and social behaviors in young children of English-speaking Caribbean immigrants. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(2), 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K. M., Adelson, J. L., Callahan, C. M., Houlihan, D. V., & Keizer, B. M. (2013). Gifted students’ perceptions of parenting styles: Associations with cognitive ability, sex, race, and age. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq Sangawi, H., Adams, J., & Reissland, N. (2015). The effects of parenting styles on behavioral problems in primary school children: A cross-cultural review. Asian Social Science, 11(22), p171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samartzis, L., & Talias, M. A. (2019). Assessing and improving the quality in mental health services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sameroff, A. (2009). The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadi, Y., & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. (2023). Psychological and social consequences of divorce emphasis on children well-being: A systematic review. Preventive Counseling, 4(2), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, H., Moirangthem, S., & Van Der Waerden, J. (2024). The impact of paternal mental illness on child development: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(11), 3693–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R. D., Siegel, B. S., Council on Child Abuse and Neglect, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Flaherty, E. G., Gavril, A. R., Idzerda, S. M., Antoinette “Toni”, A., Legano, L. A., Leventhal, J. M., Lukefahr, J. L., Yogman, M. W., Baum, R., Gambon, T. B., Lavin, A., Mattson, G., Montiel-Esparza, R., & Wissow, L. S. (2018). Effective Discipline to raise healthy children. Pediatrics, 142(6), e20183112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipp, V., Hagelweide, K., Stark, R., Weigelt, S., Christiansen, H., Kieser, M., Otto, K., Reck, C., Steinmayr, R., Wirthwein, L., Zietlow, A., Schwenck, C., & The COMPARE-Family Research Group. (2024). Parenting stress in parents with and without a mental illness and its relationship to psychopathology in children: A multimodal examination. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1353088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M. D., & Hooker, S. A. (2018). Supporting families managing parental mental illness: Challenges and resources. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 53(5–6), 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloover, M., Stoltz, S. E. M. J., & Van Ee, E. (2024). Parent–child communication about potentially traumatic events: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(3), 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solem, M.-B., Christophersen, K.-A., & Martinussen, M. (2011). Predicting parenting stress: Children’s behavioural problems and parents’ coping. Infant and Child Development, 20(2), 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H., Bate, J., Steele, M., Dube, S. R., Danskin, K., Knafo, H., Nikitiades, A., Bonuck, K., Meissner, P., & Murphy, A. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and parenting stress. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 48(1), 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. L., Celebre, A., Semovski, V., Hirdes, J. P., Vadeboncoeur, C., & Poss, J. W. (2022). The interRAI child and youth suite of mental health assessment instruments: An integrated approach to mental health service delivery. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 710569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S. L., Hirdes, J. P., Curtin-Telegdi, N., Perlman, C., MacLeod, K., Ninan, A., Hall, M., Currie, M., Carson, S., Morris, J. N., Berg, K., Björkgren, M., Declercq, A., FinneSoveri, H., Fries, B. E., Gray, L., Head, M., James, M., Ljunggren, G., … Topinková, E. (2015). InterRAI Child and Youth Mental Health (ChYMH) assessment form and user’s manual, Version 9.3. interRAI. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S. L., Lapshina, N., & Semovski, V. (2021a). Interpersonal polyvictimization: Addressing the care planning needs of traumatized children and youth. Child Abuse, 114, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S. L., Toohey, A., & Poss, J. W. (2021b). iCCareD: The development of an algorithm to identify factors associated with distress among caregivers of children and youth referred for mental health services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 737966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S. L., Vasudeva, A., Hirdes, J. P., & Poss, J. W. (n.d.). Resource intensity in children and youth: Capturing characteristics related to complex service needs.

- Swartz, K., & Collins, L. G. (2019). Caregiver Care. American Familt Physician, 99(11), 699–706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- United Nations (UN). (2024). List of least developed countries (as of 19 December 2024). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/ldc_list.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Wang, W., & Li, M. (2023). Daily work stress and parent-to-child aggression: Moderation of grandparent coresidence. Chinese Sociological Review, 55(3), 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J., Lloyd-Richardson, E., Fisseha, F., & Bates, T. (2018). Parental secondary stress: The often hidden consequences of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittle, S., Pozzi, E., Rakesh, D., Kim, J. M., Yap, M. B. H., Schwartz, O. S., Youssef, G., Allen, N. B., & Vijayakumar, N. (2022). Harsh and inconsistent parental discipline is associated with altered cortical development in children. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 7(10), 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, S., Zhang, L., & Rakesh, D. (2025). Environmental and neurodevelopmental contributors to youth mental illness. Neuropsychopharmacology, 50(1), 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, M., & Paas, F. (2022). Harsh physical discipline and externalizing behaviors in children: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, L. A., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Burgess, A. (2021). Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents following their child’s single-event trauma: A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and risk factor correlates. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(4), 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J., Kurdyak, P., & Guttmann, A. (2016). Developing indicators for the child and youth mental health system in ontario. Healthcare Quarterly, 19(3), 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zapf, H., Boettcher, J., Haukeland, Y., Orm, S., Coslar, S., & Fjermestad, K. (2024). A systematic review of the association between parent-child communication and adolescent mental health. JCPP Advances, 4(2), e12205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. (2020). Quality matters more than quantity: Parent–child communication and adolescents’ academic performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Caregiver Distress | Family Function | Parenting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Worse | Improved | Worse | Improved | Worse | ||

| Child/ youth | Male | ↑ | ↓ | ||||

| Greater age | ↓ | ↕ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |

| Any of 4 traumas | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ||

| Considered self-injury in last year | ↓ | ||||||

| Disruptive/poor productivity at school | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| High level of externalizing behaviours | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |

| Psych. symptoms worse in last 30 days | ↑ | ||||||

| Inadequate problem solving | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| Parents/ family | Unavailable unpaid support | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | |

| Parent has developmental/MH issues | ↓ | ↑ | |||||

| Major life stressor in last 90 days | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| Caregiver expresses anger, depression, or distress | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |||

| Provider/ system | Inpatient | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| 6+ months between assessments | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| RIChY-2 scale values | Assigned to low strata | 1–5 | 1, 2 | 1–5 | 1–3 | 1–4 | 1–3 |

| Assigned to middle strata | 6–9 | 3–7 | 6–9 | 4–8 | 5–8 | 4–8 | |

| Assigned to high strata | 10 | 8–10 | 10 | 9, 10 | 9, 10 | 9, 10 | |

| Prevalence (All) | |

|---|---|

| N (assessment pairs) | 14,892 |

| Quality Indicator outcomes: | |

| Caregiver distress improved (of 5397 eligible pairs) | 46.7% |

| Caregiver distress worsened (of 9495 eligible pairs) | 8.7% |

| Family function improvement (of 6766 eligible pairs) | 56.9% |

| Family function worsened (of 13,614 eligible pairs) | 9.8% |

| Parenting strength improvement (of 6199 eligible pairs) | 58.2% |

| Parenting strengths worsened (of 13,235 eligible pairs) | 14.8% |

| Covariate prevalence | |

| Sex: male | 52.7% |

| Age: 4 to 7 | 13.2% |

| 8 to 11 | 33.9% |

| 12 to 14 | 27.7% |

| 15 to 18 | 25.2% |

| Mean (std) | 11.7 (3.4) |

| Any of 4 traumas | 41.9% |

| Considered self-injury in last year | 34.8% |

| Disruptive/poor productivity at school | 33.3% |

| High level of externalizing behaviours | 19.6% |

| Psychiatric symptoms worse in last 30 days | 12.1% |

| Inadequate problem solving | 44.2% |

| Unavailable unpaid support | 23.5% |

| Parent has developmental/MH issues | 46.2% |

| Major life stressor in last 90 days | 25.6% |

| Caregiver expresses anger, depression, or distress | 35.2% |

| Inpatient | 6.2% |

| 6+ months between assessments | 29.7% |

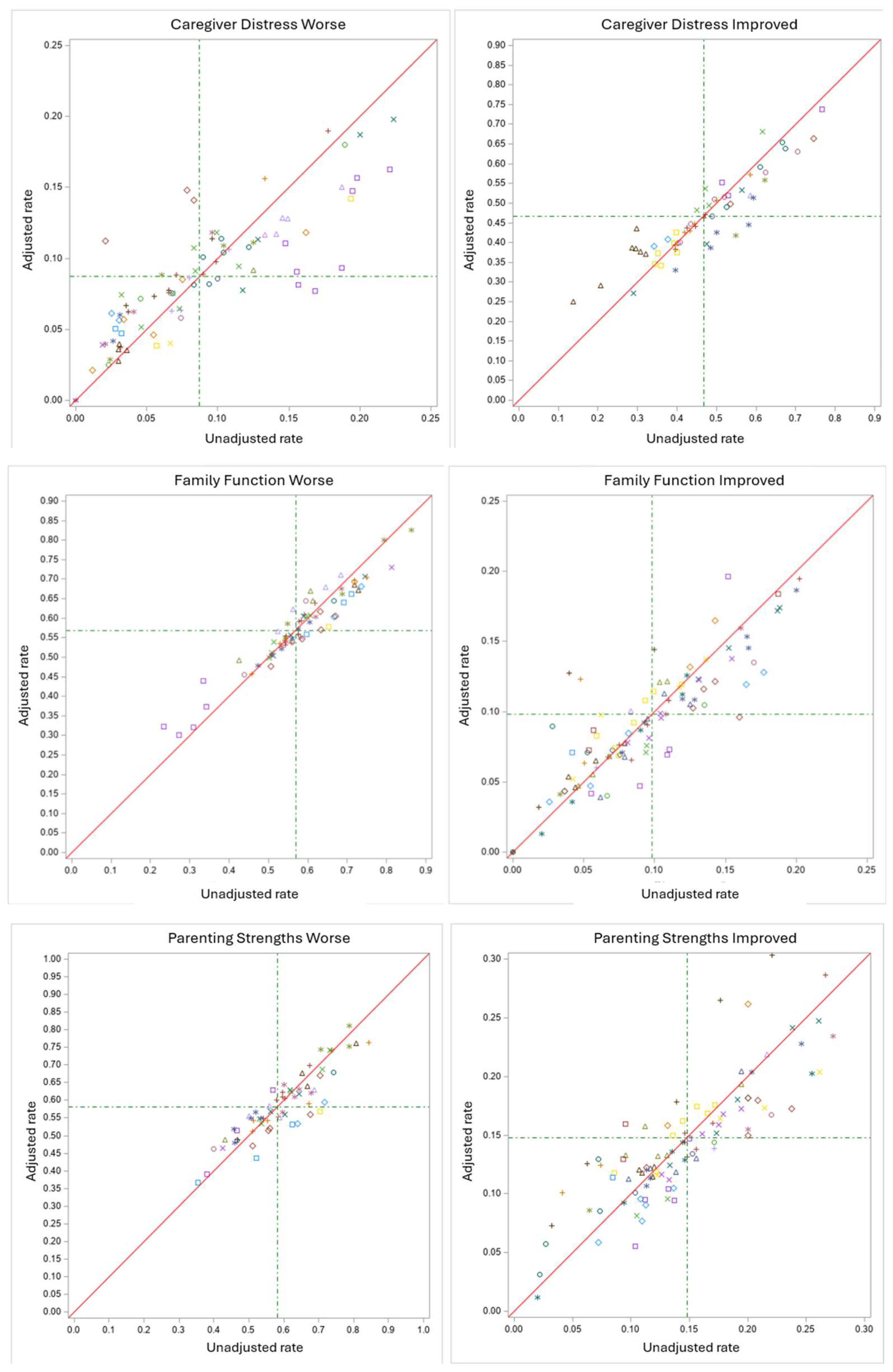

| Adjusted Agency Rate Percentiles | Correlation: Raw and Adjusted Rates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Indicator | Number of Rates | P5 | P20 | Median | P80 | P95 | With Covariates | Strata Alone, No Covariates |

| Caregiver distress improved | 58 | 26.9% | 39.2% | 45.1% | 54.5% | 64.4% | 0.927 | 0.979 |

| Caregiver distress worse | 86 | 2.8% | 5.5% | 8.5% | 12.7% | 16.6% | 0.850 | 0.942 |

| Family function improved | 69 | 37.3% | 51.2% | 57.8% | 66.9% | 71.1% | 0.957 | 0.984 |

| Family function worse | 96 | 3.2% | 6.0% | 9.1% | 12.3% | 17.4% | 0.874 | 0.917 |

| Parenting strengths improved | 62 | 44.3% | 50.4% | 57.7% | 65.6% | 79.4% | 0.904 | 0.966 |

| Parenting strengths worse | 96 | 6.0% | 10.8% | 13.4% | 17.5% | 25.5% | 0.866 | 0.942 |

| Pearson Correlation of Agency Rates; n Varies from 51 to 94 | Quality Indicator: Improvement | Quality Indicator: Worse | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Distress | Family Function | Parenting Strengths | Caregiver Distress | Family Function | Parenting Strengths | ||

| Quality Indicator: improvement | Caregiver distress | 0.63 | 0.38 | −0.38 | −0.06 | −0.08 | |

| Family function | 0.42 | −0.39 | −0.16 | 0.05 | |||

| Parenting strengths | −0.15 | −0.24 | −0.44 | ||||

| Quality Indicator: worse | Caregiver distress | 0.46 | 0.46 | ||||

| Family function | 0.54 | ||||||

| Parenting strengths | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stewart, S.L.; Brock, B.D.; Withers, A.; Guerville, R.M.; Morris, J.N.; Poss, J.W. The Development of Quality Indicators to Assess Family Wellbeing Outcomes Following Engagement with Children’s Mental Health Services in Ontario, Canada. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100212

Stewart SL, Brock BD, Withers A, Guerville RM, Morris JN, Poss JW. The Development of Quality Indicators to Assess Family Wellbeing Outcomes Following Engagement with Children’s Mental Health Services in Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(10):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100212

Chicago/Turabian StyleStewart, Shannon L., Boden D. Brock, Abigail Withers, Renee M. Guerville, John N. Morris, and Jeffrey W. Poss. 2025. "The Development of Quality Indicators to Assess Family Wellbeing Outcomes Following Engagement with Children’s Mental Health Services in Ontario, Canada" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 10: 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100212

APA StyleStewart, S. L., Brock, B. D., Withers, A., Guerville, R. M., Morris, J. N., & Poss, J. W. (2025). The Development of Quality Indicators to Assess Family Wellbeing Outcomes Following Engagement with Children’s Mental Health Services in Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(10), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100212