1. Introduction

Sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) can be defined as a personality trait that reflects individual characteristics of sensitivity to internal and external stimuli [

1]. People carrying this trait are known as Highly Sensitive People (HSP) and are characterized by high emotional and empathic responsiveness and deeper information processing capabilities [

2]. It is important to note that being highly sensitive is considered a neutral psychological trait and not a disorder. While HSP have several strengths, such as being more aware of their environment or having better information processing, it may also come with challenges, such as a higher likelihood of experiencing stress or anxiety in certain situations [

3].

Aron describes high sensitivity as a dual-faceted attribute encompassing both favorable and unfavorable dimensions [

4]. HSP are believed to be particularly sensitive to sensory stimulation, easily excitable, and particularly attentive to aesthetic impressions [

5]. Despite the potential desirability of these characteristics, on the contrary, HSP struggle to find their place in societies whose members, for the most part, do not share these characteristics. For instance, HSP are distinguished by great emotional reactivity and empathy, which could be described as higher emotional intelligence, as well as the ability to process information more deeply [

6], which makes them more vulnerable to external influences, easily influenced, and susceptible to sudden hyperactivity [

7].

Initially, the first investigations viewed sensitivity as a vulnerability [

8]. However, recent studies have revealed adaptive characteristics of individuals with elevated levels of SPS, such as more positive emotions in supportive environments [

9,

10]. Recent studies also demonstrate that individuals with elevated levels of SPS have a heightened ability to respond to both positive and negative experiences [

11]. This special sensitivity towards the environment has implications for health, education, and work. In fact, authors such as Costa-López et al. have hypothesized that HSP would have a decrease in communication skills [

12], which are so relevant in the interaction between patients and healthcare professionals. This is especially important considering that the prevalence of SPS in the general population is higher than expected, placing this figure around 30% [

13,

14]. Moreover, it has also been described that SPS is a crucial factor that not only affects happiness or quality of life but also functional or physiological levels [

1,

12].

Aron et al. believe that SPS is a key factor that affects not only health or quality of life but also at a functional or physiological level [

4]. Moreover, SPS is biologically associated with heightened awareness and the ability to respond to environmental and social stimuli [

4]. These people are characterized by being good observers and highly creative. However, they are introverts and can easily suffer from important levels of stress. As a whole, although it has not yet been studied in depth, HSP could have difficulties with conflict resolution both in work, social, or educational environments.

During their college years, nursing students spend much time in classrooms, clinical simulation rooms, and academic clinics, where they are exposed to a variety of life experiences that are emotionally challenging and can affect their future development and well-being. Some studies have hypothesized that stress is pervasive in all aspects of undergraduate nursing education [

11,

15] and that SPS may negatively respond to these environments and develop stress-related problems [

16]. This period of study is also characterized by increased vulnerability to various mental health challenges [

17], and therefore, the educational context can have an important influence on students’ personal and professional development. In this regard, positive educational environments may reinforce the positive features of SPS. However, the impact of environmental factors is subjected to individual variability, wherein a context considered positive by some may manifest as adverse for others.

The identification of the SPS trait in nursing students is of great relevance, particularly from an individualized perspective, which may help to conduct the necessary interventions to promote the positive aspects of this trait. Within this context, machine learning (ML) emerges as a field of study in the branch of algorithm evolution that gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed and emulate human intelligence learning from their data environment [

18]. ML algorithms allow for the development of predictive models at the individual level; given the complexity of the SPS trait and its correlation with specific emotion regulation difficulties, relying solely on classical regression models, which necessitate the formulation of a priori hypotheses, may limit the exploration of these connections. On the other hand, ML techniques investigate probabilistic relationships between variables and employ repeated cross-validation methods to ascertain the reliability of findings [

19]. Supervised machine learning entails the development of a statistical model based on a set of example or training data, which aid in pattern recognition for the future modeling of new datasets. Indeed, the application of machine learning in psychology and psychiatry research has seen a significant increase, and ML techniques have been employed for detecting depression, anxiety, and apathy [

20], posttraumatic stress disorder [

21], and other psychiatric conditions (schizophrenia, anorexia, substance abuse) [

22]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no earlier study has been conducted with this methodology within the context of HSP. In this line, several machine learning algorithms were conducted to analyze the particularities of SPS through their interaction with emotion regulation, social skills, and conflict resolution styles. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the presence of the SPS trait in nursing students and to evaluate the possible differences in emotional intelligence dimensions, communication skills, and conflict resolution styles. All of this is in order to try to develop a predictive model that allows us to detect HSP early, which, in turn, would help targeted interventions aimed at reinforcing the advantageous characteristics associated with this trait.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The present cross-sectional study was conducted in a university setting. Data collection took place during 2022. For the development of the present work, we initially collected data from 1190 nursing students, of which only 672 completed all evaluations, and therefore, were considered the study sample.

The form was submitted in digital Google Form format. A single form including all determinations was developed. A QR code was made to facilitate access to the questionnaire. Each student filled out the form from their electronic devices. A researcher was present to make the pertinent instructions for carrying out the tests. Previously, an explanatory presentation was designed on how to fill out the forms.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University (#CE061902), respecting the agreements of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964. The participants were informed of the characteristics of the study in addition to the purpose of the data obtained. By completing the questionnaire, they gave their consent. The data collection process was conducted during class time and the decision to take part was free and voluntary, without a compensation agreement and without disadvantages for students who chose not to take part.

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

The following instruments were used to collect the data:

Custom sociodemographic variables questionnaire: A specific survey was designed for this study. The questionnaire was composed of six items: sex, age, marital status, cohabitation group, and self-perception of the quality of relationships with family, couples, and social mates.

Reduced Scale for Highly Sensitive People (r-HSP): The validated diagnostic test for finding individuals with the sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) trait is the 27-item Highly Sensitive Persons scale (HSP scale), developed by Aron and Aron [

1]. This instrument is extensively used to assess the environmental sensitivity of both students and adults. Originally, the HSP scale, consisting of twenty-seven items, was developed by Aron and Aron in 1997. The present work employed the reduced version (r-HSP), including sixteen items with values ranging from 0 to 16; the r-HSP scale measures sensitivity, with a higher score showing greater sensitivity. The reliability of the Spanish version of the r-HSP scale was assessed through Cronbach’s α, yielding an acceptable value of α = 0.702 [

23].

Test of perceived emotional intelligence (TMMS-24): The Trait Meta Mood Scale 24 is a measurement instrument based on the emotional meta-knowledge of the subjects, based on which three dimensions of emotional intelligence, attention, clarity, and emotional repair, are evaluated. Originally, it had forty-eight items, with Likert-type responses. The TMMS-24 is a reduced version adapted to Spanish, developed by Fernández Berrocal et al. [

24,

25], which keeps the same format as the original TMMS [

25], with good psychometric qualities for the Spanish-speaking population. Through twenty-four items, it evaluates three factors or dimensions (eight items per factor): attention to feelings, emotional clarity, and repair of emotions. Attention to feelings is the degree to which people believe they pay attention to their emotions and feelings (i.e., “I think about my mood constantly”); emotional clarity refers to how people believe they perceive their emotions (“I frequently make mistakes with my feelings”); and finally, emotional repair refers to the subject’s belief in their ability to interrupt and regulate negative emotional states and prolong positive ones (i.e., “Although sometimes I feel sad, I usually have an optimistic outlook.”). The internal reliability of the original instrument was 0.95 (95%). Likewise, for each of the dimensions, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient measurements obtained were greater than 85%.

Scale on communication skills in health professionals (EHC-PS): This scale is composed of eighteen items, with a Likert-type response scale. This scale has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties. The reliability analysis showed (internal consistency with Cronbach’s α in all its dimensions between 0.65 and 0.78). The four dimensions that make up the scale are informative communication, composed of 6 items, which reflects the way that health professionals obtain and provide information in the clinical relationship that they establish with patients; empathy, composed of 5 items, which reflects the ability of health professionals to understand the patients’ feelings, as well as the empathic attitude, including active listening and empathic response. The factor respect, composed of three items, evaluates the respect that health professionals show in the clinical relationship they establish with patients. Finally, the social skills factor reflects the ability of health professionals to be assertive or socially skilled in the clinical relationship they set up with patients [

26].

Thomas–Kilmann’s Conflict Style Assessment: The Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Survey Instrument (TKI) is a forced-choice measure comprised of thirty statement pairs, each illustrating one of the five conflict modes. Respondents are required to select one statement from each pair that best represents their approach to conflict situations. Each conflict mode is presented 12 times, allowing for a maximum score of 12 for each mode. Scores are then categorized as either HIGH or LOW for each conflict mode based on whether they fall within the top or bottom 25th percentile, respectively.

Participants were instructed to complete the TKI instrument considering their responses in a work context, rather than a home setting. The Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Survey Instrument assesses five conflict resolution strategies: avoidance, accommodation, competition, compromise, and collaboration. Widely recognized as one of the premier tools for identifying conflict management styles, the TKI has demonstrated reliability coefficients ranging from 0.61 to 0.68 in test–retest analyses and between 0.43 and 0.71 with Cronbach’s alpha [

27].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics of frequency (percentage) and dispersion (mean and standard deviation) were analyzed. Taking into account the high sample size, normality was studied according to the Kruskal–Wallis test. Furthermore, to analyze the relationship between qualitative variables (nominal or ordinal), such as the relationship between sex and the diagnosis (positive or negative) of HSP, the chi-square test was used. When the mean values of two independent groups were analyzed, the t test was analyzed. The effect size in this case was measured with Cohen’s d statistic. When more than two groups were evaluated, a one-way ANOVA was used, where the eta-squared value was used as a measure of the effect size. To develop the HSP predictive model, a multivariable logistic regression procedure was used, where variables were included according to the stepwise procedure. Only those variables with any significant association with the diagnosis of HSP were included in the first model. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 27.0 software. A value of statistical significance was established for a value of p < 0.050.

2.4. Machine Learning Procedure

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of artificial intelligence that focuses on the development of algorithms and models that can learn and make predictions or decisions based on data, without being explicitly programmed. In the context of our study, we employed ML techniques to develop predictive models for identifying the presence of the SPS trait among nursing students. By leveraging the power of ML, we aimed to uncover complex patterns and relationships in the data that may not be apparent through traditional statistical methods.

The first step of the machine learning (ML) procedure was a meticulous preprocessing to ensure the integrity and accuracy of the analysis, which involved outlier removal and data curation. Next, we addressed the issue of low variance in the dataset. Variables that showed less than 5% variance were removed, because variables with minimal variance contribute little to no meaningful information and can impede the performance of predictive models. In addition, those variables exhibiting high correlation were also removed from the final dataset. Specifically, variables with more than 90% correlation were eliminated. This action helps to reduce multicollinearity, ensuring that our models are not biased or overfitted due to highly correlated predictors. In addition, we applied one-hot encoding to several categorical variables to better capture their nuances in our analysis. These variables included ‘Academic Year’, which is the academic period of the study; ‘Previous Health Education’, indicating the level of health education received prior to the study; ‘Perception of Relationships with Relatives’, ‘Perception of Relationships with Couples’, and ‘Perception of Social Relationships’. These encodings transformed the categorical data into a format that can be easily used by ML algorithms, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness and depth of our analysis.

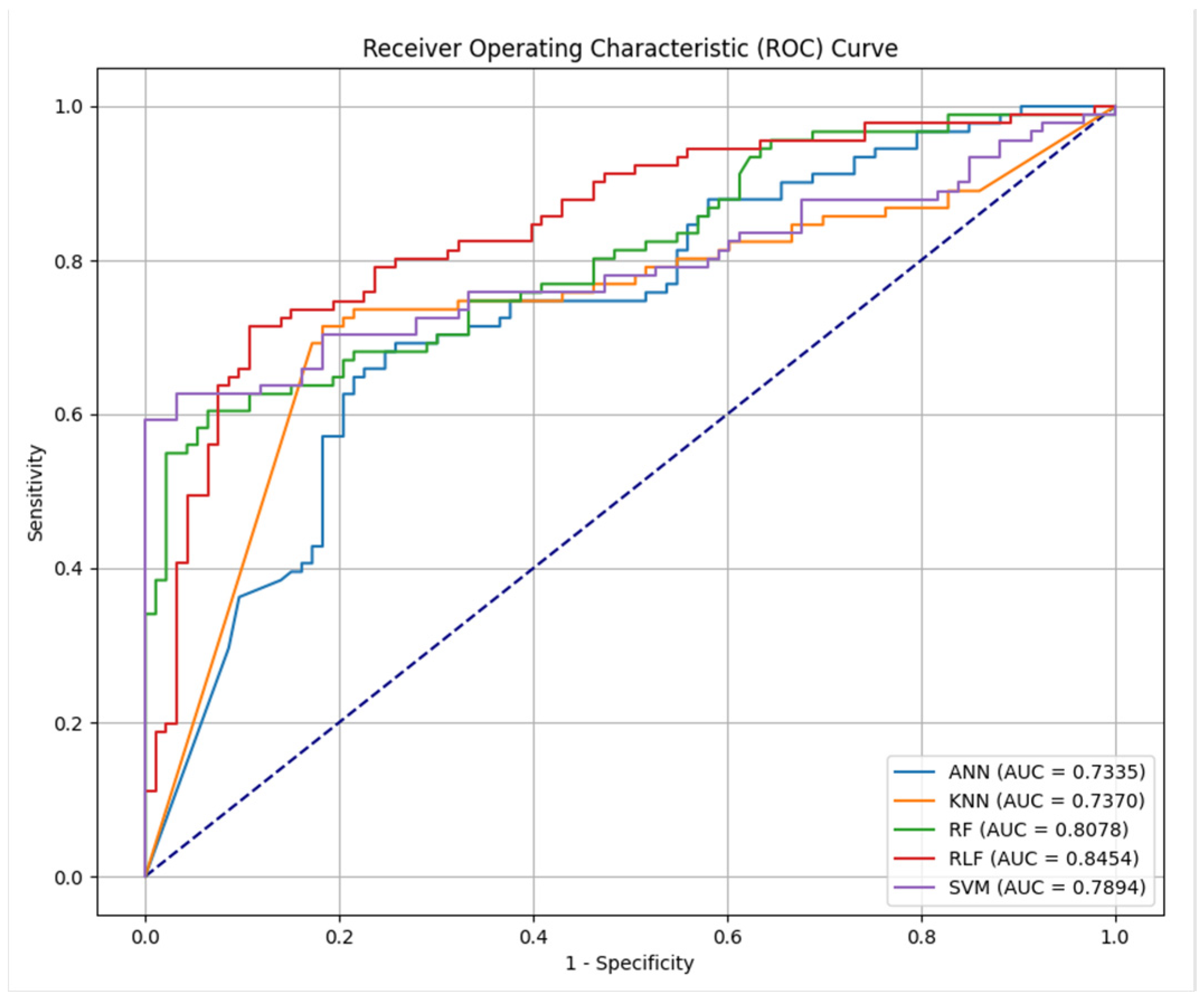

We evaluated several ML algorithms, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), which are inspired by the structure and function of the human brain; K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs), which makes predictions based on the similarity of data points; Random Forest (RF), which combines multiple decision trees to make robust predictions; RuleFit (RLF), which generates interpretable rules from the data; and Support Vector Machines (SVMs), which find optimal boundaries to separate different classes of data. These calculations were performed with the SIBILA tool [

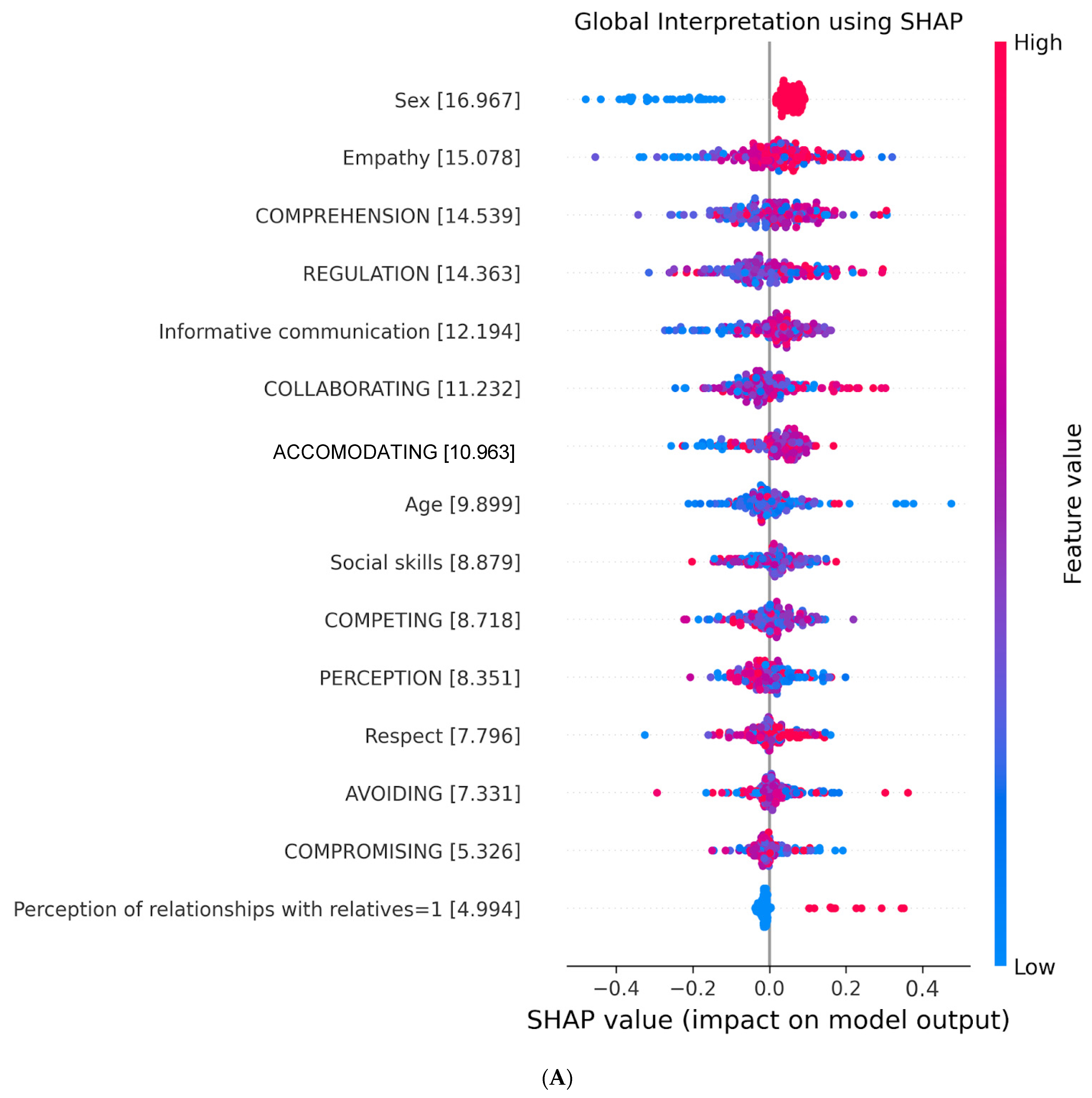

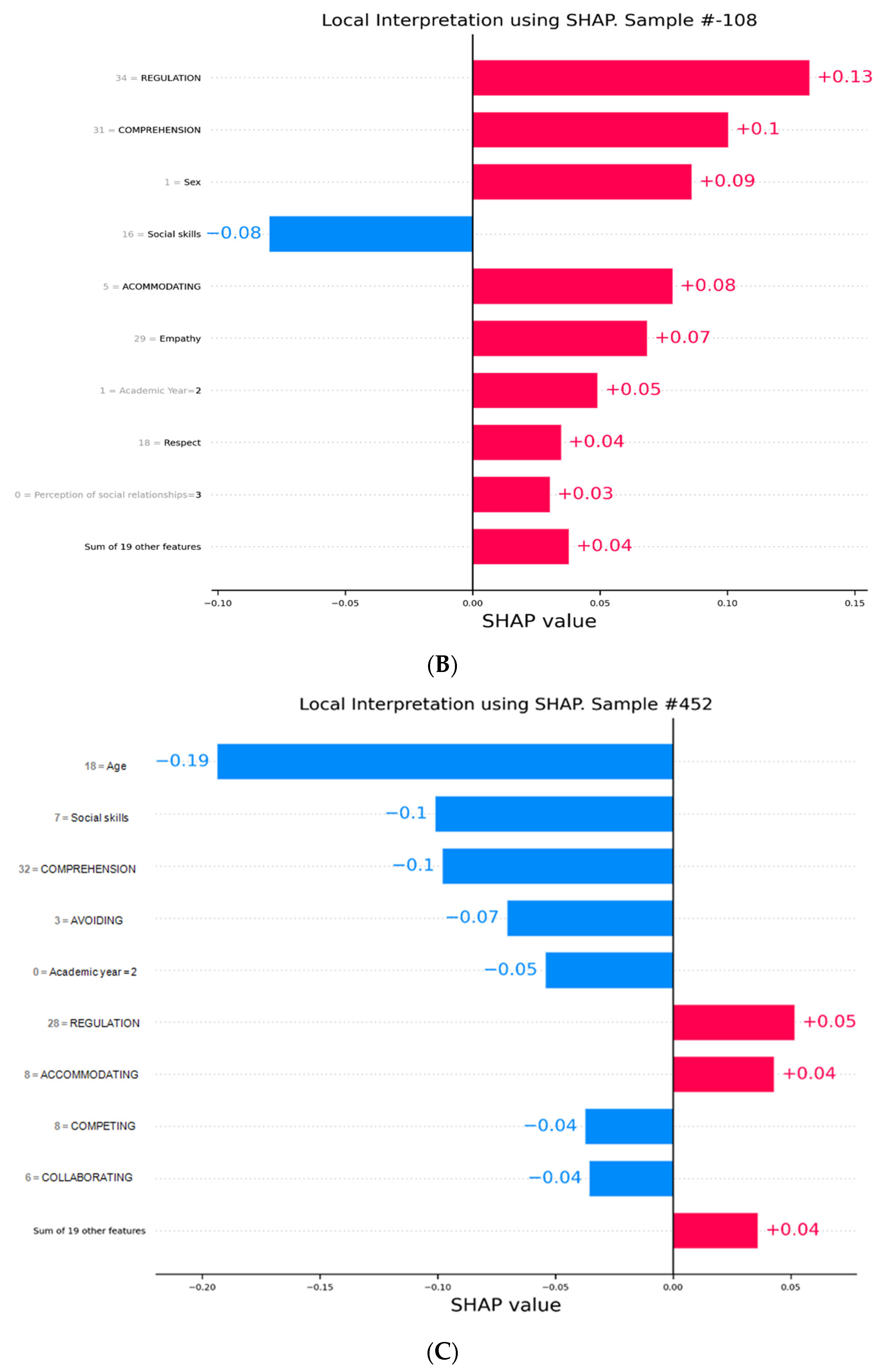

28]. Only models obtained with AUC > 0.75 were selected for later analysis with interpretability techniques. We employed techniques such as Feature Importance, which identifies the most influential predictors; Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), which explains individual predictions by approximating the model locally; and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), which assigns importance values to each feature based on their contribution to the model’s output. The employed workflow is depicted in

Supplementary Figure S1.

These interpretability techniques enhance the transparency of our models by providing insights into the key predictive features and their contributions, making the decision-making process more accessible and understandable for practical applications.

4. Discussion

The present work emerged with the aim of developing a predictive model capable of the early identification of those individuals with the sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) trait, who are identified as Highly Sensitive People (HSP). HSP are characterized by increased sensory processing and emotional reactivity. Understanding the prevalence and gender differences in HSP is essential for understanding individual variations in sensitivity and potential implications for their well-being and psychological functioning [

13].

The prevalence data from the study revealed a global prevalence of 33%, remarkably similar to what was described in earlier studies [

13,

14], although there was a higher prevalence of HSP among women compared to men. However, no significant differences were found in age with respect to the HSP diagnosis. Previous studies have described that this trait is more frequent among nursing students and health professionals [

29].

In the present work, the prevalence of HSP was similar throughout all the academic years of nursing students; however, those with previous university or technical health education showed a higher HSP prevalence than those without previous formation. Understanding how academic training can influence the manifestation of SPS is essential for a more complete understanding of this personality trait. The higher prevalence of HSP in those with previous university education and technical training was also described previously [

30]. This demonstrates the possibility that exposure to broader and more specialized educational experiences may influence the development or recognition of high sensitivity, emphasizing the role of previous academic formation over the nursing academic training.

The perception of the relationship with relatives can influence the experience and manifestation of the characteristics of HSP [

1]. Contrary to what may be expected, in the present work, those with a very unsatisfactory perception of relationships with relatives showed a higher probability of being HSP. Therefore, as indicated previously by Hofmann and Bitran, the perception of social relationships is relevant regarding the sensitivity and characteristics of HSP [

31].

When exploring the relationship between HSP and emotional intelligence, it is important to consider the multifaceted construct that encompasses several components of emotional intelligence. HSP often exhibit heightened sensitivity to emotional cues, allowing them to be more attuned to their own emotions and those of others [

32]. This enhanced emotional awareness may contribute to their ability to recognize and accurately identify emotions in themselves and others. HSP may have a greater capacity for perceiving and understanding subtle emotional expressions and nonverbal cues [

4]. In this line, we observed higher emotional repair in HSP, which may be a consequence of the presence of the SPS trait in these individuals.

The association between HSP and communication skills is also of great relevance. Firstly, it is important to note that there are individual differences among HSP, and not all HSP will have the same level of communication abilities. HSP often have heightened sensory processing, making them more susceptible to sensory overload in certain environments or during intense communication situations [

26]. This sensory overload can potentially impact their ability to effectively communicate and process information in real time. HSP may require more time and space to regulate their sensory input, which could affect their communication style [

1].

Concretely, and in line with the current observations, HSP often show a heightened ability for empathy. They may have an innate ability to understand and share the emotions of others, leading to greater compassion and interpersonal sensitivity [

32]. This empathetic nature allows HSP to connect with others on a deeper level and respond empathically to their emotional experiences. Similarly, respect and informative communication were also more elevated in HSP, which may also be associated with the characteristics of HSP. For instance, they are characterized by heightened awareness that can lead to a more respectful and considerate approach in interpersonal relationships. Moreover, highly sensitive individuals often engage in introspection and self-reflection. This self-awareness can lead to a better understanding of their own actions and how they impact others, fostering a greater sense of respect in their interactions.

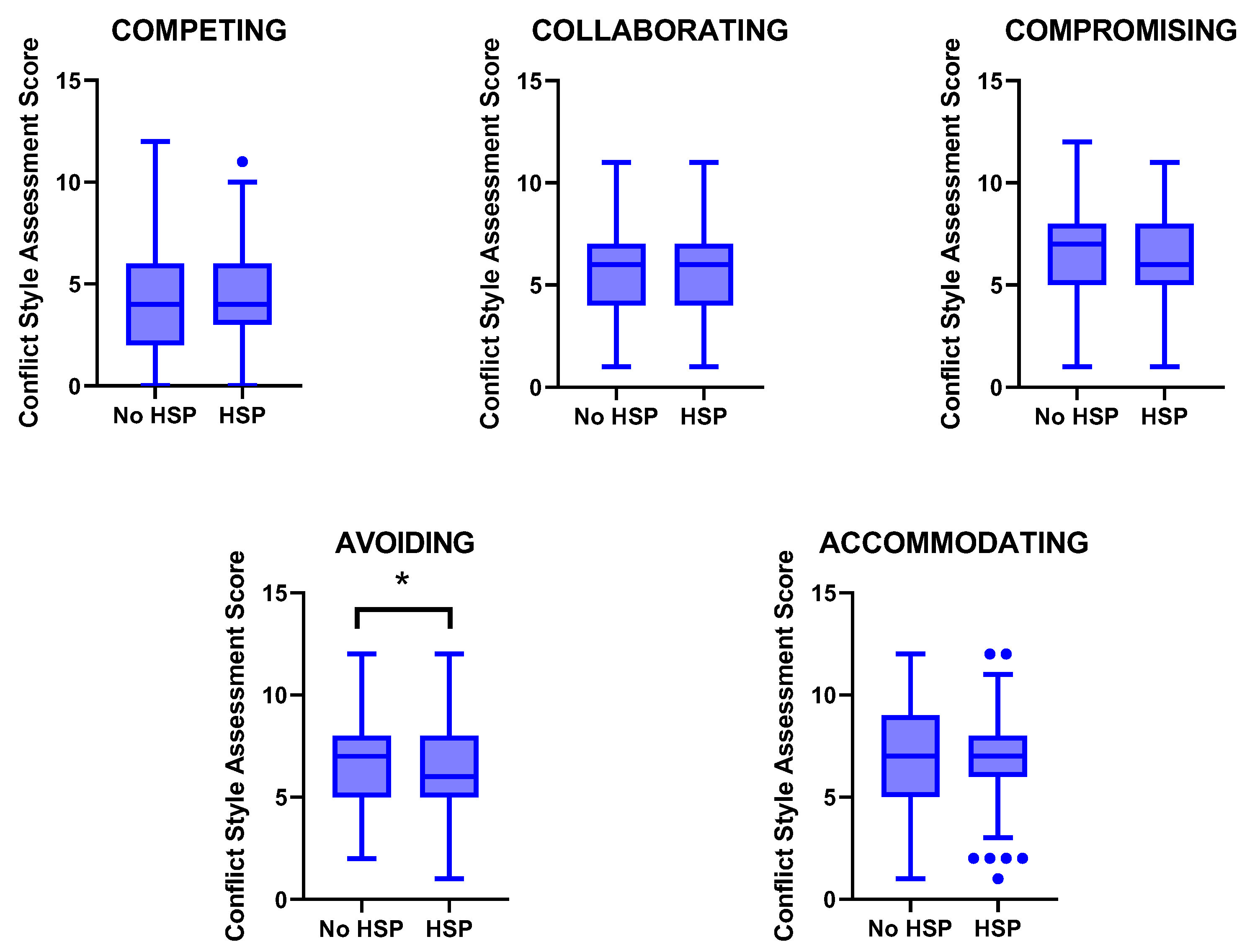

In the context of conflict styles, the Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) is a widely used assessment that measures individuals’ preferred approaches to conflict resolution. Attending to the data obtained, HSP showed lower avoiding and compromising styles compared with those without the SPS trait. These observations are somewhat controversial because, while the relationship between HSP and conflict styles has not been extensively researched, it is possible to discuss potential conflict styles that HSP may show based on general observations and characteristics associated with high sensitivity. For instance, HSP typically have a strong aversion to conflict and a desire for harmony [

30]. This preference may lead them to avoid or downplay confrontational or challenging communication situations. HSP may prioritize keeping peace and avoiding arguments, which can sometimes result in less assertive or direct communication styles, potentially hindering their ability to effectively express themselves in certain contexts.

Therefore, the observation that HSP are less avoidant is, in principle, contrary to what one would expect. On the other hand, HSP often engage in the deep processing of information and emotions. They may take more time to carefully consider their thoughts and responses before communicating them [

26]. While this trait can contribute to thoughtful and well-considered communication, it may also result in slower response times during fast-paced or spontaneous conversations, which can be perceived as a lack of communication skills in certain situations. This could partially explain the lower compromising, a conflict resolution style that aims to find a mutually acceptable solution to the conflict while maintaining some assertiveness and cooperativeness, observed in the data derived from HSP. However, as commented above, it is important to note that individual differences exist within the HSP population, and not all HSP will have the same conflict style [

33]. In addition, an HSP’s preferred conflict style can also be influenced by factors such as cultural background, individual personality traits, and contextual factors [

17].

Focusing on the main aim, namely, to find a predictive model to detect HSP early, a double approach has been conducted. Firstly, a classic logistic model was developed using HSP diagnosis as the dependent variable. This procedure revealed that sex, previous health education, and the perception of relationships with relatives were the main predictors of HPS, over emotional intelligence and conflict resolution styles. Previously, Drndarevic et al. have described the link between SPS and emotional intelligence [

34], which reinforces, in part, our observations. Moreover, informative communication, a dimension of communication skills, also predicted HSP but with less relevance than the previous factors. However, although this model yielded a high positive predictive value, other indicators like specificity were low, which encouraged the use of a machine learning (ML) framework to integrate features into a predictive model of HSP.

Attending to the ML model, as with the previous logistic one, sex was the main predictor feature for identifying HSP. However, in this case, earlier health training and the perception of relationships were not as relevant as in the classic model. Considering the higher values obtained regarding sensitivity metrics in the ML model, this procedure would be more suitable to predict the presence of the SPS trait, and therefore, the characteristics shown by this model should be considered to a greater extent than in the classic model. Other data that support this idea come from the relevance of empathy in the ML model. In this case, empathy was, after sex, the most significant factor. Additionally, McCarthy et al. also noted the importance of evaluating emotional intelligence dimensions, such as empathy, to find HSP [

35].

Communication skills, specifically informative communication, were also important predictors in both models. There are several issues that could be related to this fact. HSP often engage in the deep processing of information and emotions [

36]. They may take more time to carefully consider their thoughts and responses before communicating them. While this trait can contribute to thoughtful and well-considered communication, it may also result in slower response times during fast-paced or spontaneous conversations, which can be perceived as a lack of communication skills in certain situations. Moreover, HSP are often highly attuned to nonverbal cues and subtle emotional expressions [

13]. This sensitivity can be an asset in communication, as they may notice nuanced emotions and underlying messages. However, it can also make them more sensitive to nonverbal cues that may be perceived as negative or critical, potentially leading to heightened emotional reactions or withdrawal in communication. Additionally, effective communication skills are influenced by a combination of factors including personality traits, individual experiences, and environmental factors [

23].

When we consider conflict resolution styles as HSP predictors, the most important styles were collaborating and accommodating, although in this case, the trend was not as clear as with the other features. However, in the accommodative style, it does seem that the higher the score, the greater the probability of being HSP, which is in line with the previous observations of Labrague [

37].

Overall, the transparency and interpretability of our machine learning approach to detect SPS have significant implications for educational settings. By understanding the factors driving the prediction of the SPS trait, educators can develop targeted interventions and support strategies for HSP students. The interpretability techniques employed in our study, such as SHAP, provide actionable insights into the key predictive features and their contributions to the model’s decision-making process. This enhanced transparency enables educators to tailor their approaches based on the specific needs and characteristics of individual students, ultimately promoting a more inclusive and supportive learning environment for HSP individuals.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of our research design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the observed variables and the presence of the SPS trait. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the predictive value of the identified factors and to assess the stability of the SPS trait over time. We also thought that future work would receive help from the inclusion of a desirable prediction measure to determine the role of specific individual characteristics in the HSP diagnosis, as in the present work. It would be of scientific interest to ascertain the temporal dynamics of individual factors figuring out the components of SPS associated with heightened responsiveness in this trait, but that manifest distinct trajectories depending on individual variations [

3].

Secondly, our sample consisted of nursing students from a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations or settings. Further validation of our findings in diverse samples, including practicing nurses and individuals from different cultural backgrounds, is necessary to establish the external validity of the predictive model. Lastly, while we employed a comprehensive set of variables in our analysis, there may be additional factors, such as genetic predispositions or early life experiences, that could influence the development and expression of the SPS trait. Future research should consider incorporating a broader range of variables to enhance the predictive power of the model and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the SPS trait.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study supply valuable information on the prevalence and gender differences in HSP. The significantly higher prevalence of HSP among women suggests that women may be more likely to have the SPS trait than men. Additionally, women showed higher sensitivity scores, indicating a more intense experience of sensory processing and emotional reactivity. HSP demonstrated greater empathy and decision-making skills, allowing them to understand and connect with the emotions of others. This empathic nature can contribute to self-awareness and emotional regulation. Therefore, the early detection of HSP may help them to better regulate and manage their feelings. Several prediction models have been developed, and it can be concluded that sex, empathy, and communication skills are the main factors when predicting the diagnosis of HSP. Previous health education and the perception of relationships with relatives may also be important.

Nevertheless, when considering HSP prediction, it is important to note that while some HSP may have certain qualities that can contribute to effective emotion regulation, not all HSP will have the same level of competence. Therefore, an individualized machine learning predictive model, as conducted in the present work, may be of better interest to identify HSP early, since the relevance of the different prediction features may differ depending on factors such as cultural or environmental and other psychological variables.

In addition to the aforementioned, it is important to consider the implications of these findings in various contexts. Exploring this relatively understudied personality trait contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior and individual differences. By recognizing and acknowledging the prevalence of high sensitivity, researchers, practitioners, and society at large can develop more inclusive and tailored approaches in various domains, including mental health, education, and workplace environments.

Further investigation is called for to expand upon these findings, employing larger and more diverse samples to provide a broader representation of the population. Additionally, longitudinal studies could help assess the stability of high sensitivity over time and examine its potential associations with various outcomes, such as well-being, interpersonal relationships, and career choices.