Assessing the Relationship between Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being: Basic Psychological Need as the Mediator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being

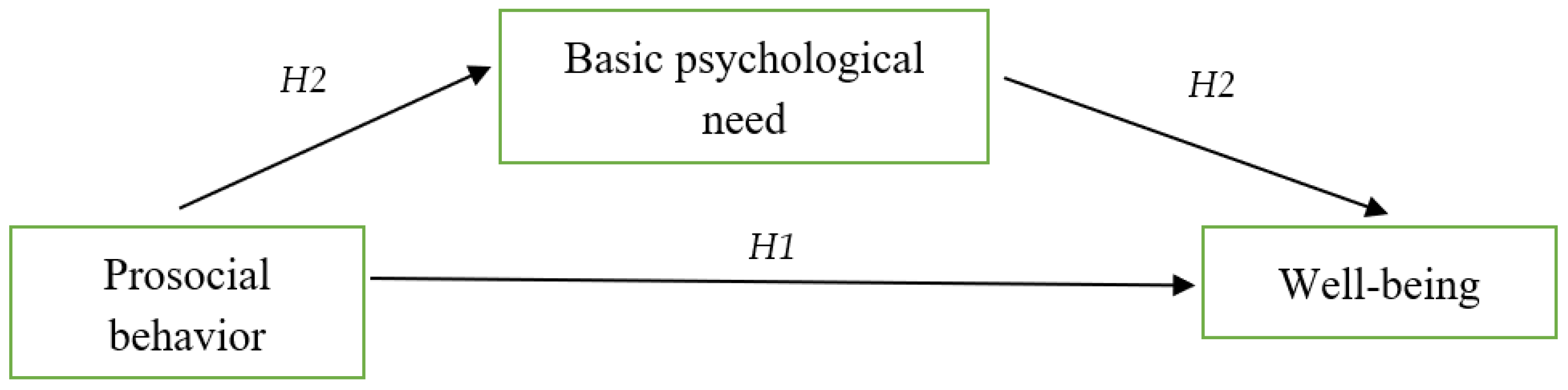

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Basic Psychological Needs

3. The Present Study

3.1. Method

Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Prosocial Behavior

3.2.2. Basic Psychological Need

3.2.3. Well-Being

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Testing the Mediating Effect

5. Discussion

The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs

6. Implications

Limitations and Future Direction

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuczera, M.; Goujon, A. Vocational Education and Training for a Global Economy: Lessons from Four Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, R.I.; Schmidt, J. The Role of Vocational Education and Training in the Labor Market Outcomes of Disadvantaged Youth. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. The Development of Vocational Education in China: A Historical Review. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y. Vocational Education, and Economic Development in China: A Study of Guangdong Province. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. The Relationship between Vocational Students’ Psychological Capital and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 73, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, E.K.; Tsang, S.K.; Law, B.M. The Relationship between Vocational Students’ Career Adaptability and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2022, 74, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaunessy, E.; Hardesty, R. Relationships among stress, coping, and mental health in high-achieving high school students. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S.; Suldo, S.M.; Smith, L.C.; McKnight, C.G. Life satisfaction in children and youth: Empirical foundations and implications for school psychologists. Psychol. Sch. 2004, 41, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Qiu, X.H.; Yang, X.X.; Qiao, Z.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Liang, Y. Depression among Chinese university students: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Phelps, E. Thriving across the life span: Toward an integrative science of positive development. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ye, J.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Miao, C.J. Analysis of influencing factors of subjective career unsuccessfulness of vocational college graduates from the Department of Navigation in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1015190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial development. Handb. Child Psychol. 2006, 3, 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Layous, K.; Nelson, S.K.; Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lyubomirsky, S. Kindness counts: Prompting prosocial behavior in preadolescents boosts peer acceptance and well-being. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e51380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, S.G.; Ng, L.E.; Fischel, J.E.; Bennett-Woods, D.; King, P. Altruism and well-being: The role of generalized trust in others. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Sci. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’ame: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; McCullough, M.E. Positive effects of prosocial behavior on well-being: The role of personal values, stress recovery experiences, and mindfulness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Ryan, R.M. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom applying self-determination theory to educational practice. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 762. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.V.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N.; Kupfer, A.; Steca, P.; Caprara, M.G.; Abela, J.R.Z. The positivity scale: Concurrent and factor validation in a large sample of young adults. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 877. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T.C. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J. Prosocial behavior: A review of the past and future directions. Adv. Psychol. 2008, 1, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 924–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Motowidlo, S.J. Prosocial organizational behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Guo, Y. The relationship between prosocial behavior and life satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.Q. The moral sense revisited. Wilson Q. 2012, 36, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, D.F.; Paine, A.L.; Perra, O.; Cook, K.V.; Hashmi, S.; Robinson, C.; Kairis, V.; Slade, R. Prosocial and aggressive behavior: A longitudinal study. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2021, 86, 7–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabes, R.A.; Carlo, G.; Kupanoff, K.; Laible, D. Early adolescence and prosocial/moral behavior I: The role of individual processes. J. Early Adolesc. 1999, 19, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, D.J.; Carlo, G.; Roesch, S.C. Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviours. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.; Youniss, J. Community service and political-moral identity in adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1996, 6, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, W.K.; Twenge, J.M.; Carter, N.T. The self-esteem motive in social comparison. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 404–418. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, X. The relationship between prosocial behavior and academic achievement among Chinese college students: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2011, 39, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-M.; Chen, Y.-L. Social support and well-being among college students in Taiwan: An analysis of mediating effects. J. Coll. Couns. 2016, 19, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zygmont, A.; Doliński, W.; Zawadzka, D.; Pezdek, K. Uplifted by Dancing Community: From Physical Activity to Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.-S. The psychological structure of Confucianism: A conceptual empirical inquiry. In Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context; Kim, U., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Lu, L.; Wu, J. The relationship between values and prosocial behavior in Chinese children. J. Moral Educ. 2004, 33, 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.; Charlin, V.; Miller, N. Positive mood and helping behavior: A test of six hypotheses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P. Prosocial agency: The contribution of values and self-efficacy beliefs to prosocial behavior across ages. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 218–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Gino, F. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogilner, C. The pursuit of happiness: Time, money, and social connection. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior (Perspectives in Social Psychology); Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, R.J.; Hicks, J.A.; Arndt, J.; King, L.A. Thine own self: True self-concept accessibility and meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, T.F.; Lambert, N.M. The benefits of giving for the giver. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 17, 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M.M.; Lyubomirsky, S.; Boehm, J.K. The role of prosocial behavior in promoting positive affect during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 2117–2137. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A.; et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Howell, R.T.; Stolarski, M. Comparing three methods to measure a balanced time perspective: The relationship between a balanced time perspective and subjective well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Gramzow, R.H. The erosion of autonomy: Motivational consequences of self-determination in social relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 756–777. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Gunz, A. Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1467–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Kasser, T. The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilardi, B.C.; Leone, D.; Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. Employee and supervisor ratings of motivation: Main effects and discrepancies associated with job satisfaction and adjustment in a factory setting. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 1789–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.G.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Deci, E.L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Ryan, R.M.; Rawsthorne, L.J.; Ilardi, B. Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the Big-Five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. A self-determination theory approach to understanding stress incursion and responses. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2010, 26, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Bettencourt, B.A. Psychological need-satisfaction and subjective well-being within social groups. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 41, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Martin, A.J.; Marsh, H.W. Self-determination as a mediator between parents’ socialization efforts and adolescents’ leisure-time physical activity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 566–585. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, P.L.; Turiano, N.A. Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M. When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M. The relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and academic burnout among Chinese college students: The mediating role of academic engagement. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Y. The relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and subjective well-being among college students: The mediating role of academic engagement. J. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 40, 942–947. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.K.; Long, L.R. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sahay, S.; Banerjee, S. Basic psychological needs satisfaction and well-being among elderly people: A study from India. J. Popul. Ageing 2018, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, E.W.; Aknin, L.B.; Norton, M.I. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 2008, 319, 1687–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, U.; Jain, M. Altruistic behavior and psychological well-being among elderly people in India: An empirical study. J. Popul. Ageing 2012, 5, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, W.; Wei, C. Emotional Intelligence and Prosocial Behavior in College Students: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Huebner, E.S. The Effects of Satisfaction of Basic Psychological Needs at School on Children’s Prosocial Behavior and Antisocial Behavior: The Mediating Role of School Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collie, R.J. Social-Emotional Need Satisfaction, Prosocial Motivation, and Students’ Positive Behavioral and Well-Being Outcomes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 25, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y. The effects of basic psychological needs satisfaction on well-being among Korean college students: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak Çetinkalp, Z.; Lochbaum, M. Basic psychological needs and subjective well-being among Turkish university students. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Félix, F.; Costa, M.; Marôco, J. Basic psychological needs and well-being in older adults: A longitudinal study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lubans, D.R.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.H.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 19.68 ± 1.57 | 1 | |||

| 2. Prosocial behavior | 3.56 ± 0.80 | −0.05 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Basic psychological need | 4.63 ± 0.76 | −0.04 ** | 0.34 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Well-being | 3.86 ± 0.64 | −0.03 * | 0.22 ** | 0.29 ** | 1 |

| Model 1 (DV:Well-Being) | Model 2 (DV:BPN) | Model 3 (DV:Well-Being) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | β | B | t | p | β | B | t | p | β | |

| Constants | 3.42 ** | 65.39 | 0.00 | - | 3.5 ** | 57.11 | 0.00 | - | 2.70 ** | 43.33 | 0.00 | - |

| Gender | −0.11 ** | −6.74 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.60 | 0.55 | −0.01 | −0.11 ** | −6.80 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| Age | −0.000 | −1.215 | 0.224 | −0.015 | −0.001 * | −1.971 | 0.049 | −0.023 | −0.000 | −0.76 | 0.45 | −0.01 |

| Only child | −0.02 | −0.803 | 0.422 | −0.010 | 0.010 | 0.484 | 0.629 | 0.006 | −0.017 | −0.95 | 0.34 | −0.01 |

| PB | 0.17 ** | 18.14 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.32 ** | 28.83 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.11 ** | 10.85 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| BPN | 0.21 ** | 19.90 | 0.00 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| F | F (221) = 96.95, p = 0.00 | F (221) = 211.13, p = 0.00 | F (221) = 161.50, p = 0.00 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Khan, A.; Rameli, M.R.M. Assessing the Relationship between Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being: Basic Psychological Need as the Mediator. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2179-2191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13100153

Li L, Khan A, Rameli MRM. Assessing the Relationship between Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being: Basic Psychological Need as the Mediator. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2023; 13(10):2179-2191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13100153

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Linwei, Aqeel Khan, and Mohd Rustam Mohd Rameli. 2023. "Assessing the Relationship between Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being: Basic Psychological Need as the Mediator" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13, no. 10: 2179-2191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13100153

APA StyleLi, L., Khan, A., & Rameli, M. R. M. (2023). Assessing the Relationship between Prosocial Behavior and Well-Being: Basic Psychological Need as the Mediator. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(10), 2179-2191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13100153