Abstract

The aim of this review was to explore the contribution of physical activity and exercise in the control and reduction of modifiable factors of arterial hypertension in telemedicine programs, assuming a multidisciplinary perspective. Searches were carried out following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses), and the research question defined using the PICOS approach (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design). The search strategy applied the following terms: blood pressure OR hypertension AND exercise OR physical activity AND telemedicine. The initial search identified 2190 records, but only 19 studies were considered eligible after checking for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following training variables were generally included: heart rate and heart rate reserve, respiratory rate, rate of perceived exertion and oxygen consumption, but no resistance training variables were found. The significant improvements on blood pressure parameters of participants diagnosed with hypertension tended to be transient. The exercise prescription was commonly based on general instructions and recommendations for exercise and hypertension. On the other hand, most of the studies including patients in cardiac rehabilitation programs used a personalized training program based on a baseline assessment, particularly following a cardiopulmonary exercise test. The inclusion of exercise professionals in multidisciplinary teams could provide a more person-oriented approach and the long-term maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

1. Introduction

High systolic blood pressure (SBP) is one of the leading risk factors globally for death [1]. In fact, the main global risks of mortality in the world are hypertension, responsible for 13% of deaths worldwide, tobacco use (9%), high blood glucose (6%), sedentary lifestyle (6%), and overweight and obesity (5%) [2]. In addition, it is estimated that the number of people living with hypertension has doubled to 1.28 billion since 1990, and about 580 million people with hypertension (41% of women and 51% of men) were unaware of their condition because they were never diagnosed [3].

There is solid evidence suggesting that physical exercise helps to combat risk factors [4,5,6]. In a recent review, Valenzuela et al. [7] highlighted the benefits of regular physical activity and exercise for the prevention and better management of hypertension. According to these authors, the use of lifestyle interventions for the prevention and adjuvant treatment of hypertension through regular exercise, body weight control and healthy eating patterns, as well as less traditional recommendations, such as stress management and promoting the number of hours of sleep, respecting the circadian cycle, are strongly recommended. However, physical inactivity is a modifiable risk factor responsible for 5.3 million deaths annually, contributing to the main non-communicable chronic diseases [8]. According to Fletcher et al. [9], the “behaviour” of physical activity (PA) is multifactorial, including social, environmental, psychological, and genetic factors.

Traditional lifestyle interventions such as group education or telephone supporting are effective at increasing physical activity levels; however, physical activity participation tends to decrease over time [10]. Consumer-based wearable activity trackers that allow users to objectively monitor activity levels are now widely available and may offer an alternative method for assisting individuals to remain physically active. The same authors also stressed that as the effects of physical activity interventions are often short-term, the inclusion of a wearable consumer activity tracker can be an effective tool to assist healthcare providers in providing monitoring and support. Despite the limited attention that physical exercise has received in medical practice [7], the use of digital or technologies in health care services (e-health) alongside with monitoring physical activity can enhance the benefits of regular physical activity and exercise for the prevention and management of hypertension.

Among the several possible e-health solutions, telemedicine is widely spread among healthcare professionals and individuals. Telemedicine can be characterized by the use of information and communication technologies to deliver remote health services to a patient or a group of patients, provided by professionals. According to Pellegrini et al. [11], telemedicine is a promising reality and has the potential to bring significant improvements to the prevention and management of hypertensive patients, as the available studies suggest a beneficial effect on blood pressure control. However, the large heterogeneity verified in the proposed interventions, and the lack of standardization of available trials, are strong limitations to the elaboration of evidence-based recommendations. A study in the United Kingdom [12] that implemented telemonitoring to verify the long-term management of widespread chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes and chronic pulmonary obstruction demonstrated a high approval rate for telemonitoring among patients. These found it powerful, convenient, and capable of improving the daily management of their illnesses. In another scoping review study, Hoffer-Hawlik et al. [13] concluded that, although the studies are still small in size and short in duration, telemedicine can offer a promising approach to improve blood pressure levels.

According to Omboni [14], telemedicine has the potential to improve patients’ blood pressure results and reduce treatment costs, in addition to allowing an assessment with real data, and accelerated delivery of best practices combined with decision-making strategies. However, although these studies stressed the importance of a physical exercise program, including guidelines for the control of arterial hypertension; and since there is already proven evidence on the safety and effectiveness of telemedicine and e-health programs in the control of risk factors for hypertension and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), in general, these studies do not consistently consider multidisciplinary teams with the presence of an exercise professional. Intervention programs considering physical activity or exercise that are customized to the individual’s needs, supervised by qualified exercise professionals, are likely to result in enhanced outcomes for patients and health service providers alike, but these are not consistently found in the literature. Therefore, our aim was to explore the contribution and effectiveness of physical activity or exercise in an intervention program using telemedicine with hypertensive patients. A multidisciplinary approach was assumed throughout this work, considering the potential benefits of integrating exercise professionals in exercise assessment, monitoring, and counseling in healthcare services. The authors intended to observe examples of good practices, providing a guide for new work perspectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strategy and Elegibility Criteria

The writing strategy of the present work followed the PRISMA guidelines—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses [15]. The research question and eligibility criteria were defined using the PICOS approach—Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design (Table 1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the present review are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

The PICOS approach—Population, Intervention, Comparison or Control, Outcome and Study design.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Information Sources

The following electronic databases were used and searched for the present systematic review: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane. The search was carried for four weeks, during the months of September and October 2021. The publication time frame was set from the 1993 until 2021, as the MeSh term “telemedicine” was introduced in 1993—delivery of health services via remote telecommunications. Specificities for the different databases: (i) in Cochrane, title and abstract had to be searched separately, and so different combinations were required; (ii) in PubMed, search was done selecting title/abstract, not keywords; and (iii) in Web of Science and in Scopus, the combination of title, abstract and keywords was termed “topic”. The only filter applied was records from 1993 until October 2021. Search strategy for PubMed: ((((physical activity[Title/Abstract]) OR (exercise[Title/Abstract])) AND (blood pressure[Title/Abstract])) OR (hypertension[Title/Abstract])) AND (telemedicine[Title/Abstract]). The only filter applied was records from 1993 until October 2021, and 504 results were obtained.

2.3. Data Extraction

A Microsoft Excel sheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmon, WA, USA) was purposely designed and prepared to extract data, assess inclusion and exclusion criteria, and identify selected articles. Registration and selection were carried out independently by two authors (S.V.; R.R.G.). At the end of the process, a meeting took place between them, during which disagreement regarding the eligibility of a study was resolved in a discussion with a third author (R.S.). All inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the PICOS strategy, were clearly identified in the Excel sheet. Following this strategy, information extracted from the studies included: (a) description of participants (age, gender, and other details provided by the authors); (b) information about the healthcare procedures using remote specifics; (c) information about the physical activity or exercise (recommendations, frequency, intensity, volume, type, monitoring); and (d) details of the intervention (duration, evaluated parameters and outcomes: clinical, physiological, quality of life and well-being).

2.4. Methodological Quality and Level of Evidence

The checklist proposed by Downs and Black [16] was used by two raters independently to assess the methodological quality of selected randomized and non-randomized comparative studies. The checklist consists of 27 items that address the following methodological components: reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias), internal validity (confounding—selection bias), and power. In the version used in the present work, twenty-six of the items were rated as yes (= 1) or no/unable to determine (= 0), while one item was rated according to a three-point scale (yes = 2, partially = 1, and not = 0). Item 27, referring to power, was changed and, instead of classifying the study according to an available range of study powers, it was verified whether the study performed the power calculation or not. Consequently, the maximum score for item 27 was 1 (a power analysis was performed) rather than 5, and therefore the highest possible score for the checklist was 28 (instead of 32), with higher scores correspond to a better methodological quality of the study. This procedure was recently used [17]. The considered thresholds or cutoff points to categorize the quality of studies were, as follows: excellent (26–28), good (20–25), fair (15–19), and poor (≤ 14) [18]. Whenever there was no agreement of evaluation between the two reviewers (R.R.G.; S.V.), a third reviewer (R.S.) was involved.

The psychometric properties of this checklist were previously analyzed (Downs and Black, 1998), including its internal consistency, test–retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and criterion validity. The checklist was ranked among the top six quality assessment tools deemed suitable for use in systematic reviews [19].

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Study Selection

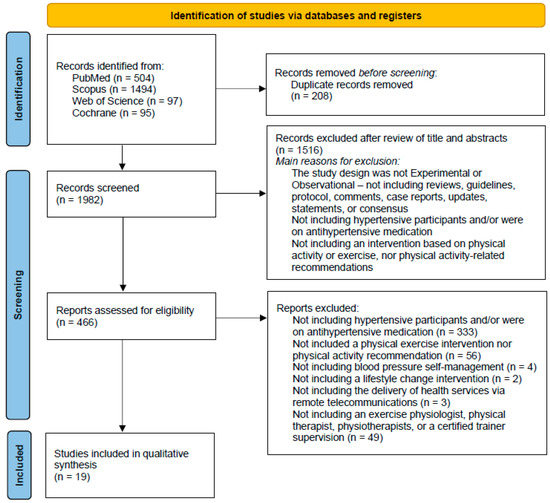

The search carried out in the consulted databases and in the records identified through citations, resulted in a total of 2190 records. After eliminating duplicate results, 1982 potentially useful records remained. Based on the title and abstract, 1516 articles were excluded, with the understanding that they did not meet the inclusion criteria: full text available, the study nature was experimental or observational (which does not included reviews, guidelines, protocols, comments, case reports, updates statements or consensus), written in English language, and only the participation of humans. The evaluation of the full texts of the remaining 466 full-text articles led to the exclusion of 447 articles. Reasons for their exclusion included the following: not including hypertensive participants and/or participants that were on antihypertensive medication (n = 333); not including a physical exercise intervention nor physical activity recommendation (n = 56); not including blood pressure self-management (n = 4); not including a lifestyle change intervention (n = 2); not including the delivery of health services via remote telecommunications (n = 3); not including an exercise physiologist, physical therapist, physiotherapists or a certified trainer supervision (n = 49). Finally, 19 articles were included in this systematic review [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], as shown in Figure 1. Two of the studies were carried out by the same first author [21,22], and despite some overlapping data as a result of a common prospective randomized controlled trial, the sample and main outcomes are different.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [15], showing the research methodology adopted in this study.

3.2. Methodological Quality

From the nineteen selected studies, eighteen consisted of prospective observational cohort studies, while only one of them was a retrospective cohort study [38]. Two of the included records had non-randomized controlled study designs [23,25], and one was a follow-up study [35].

The methodological quality ratings for each study are presented in Table 2. These ranged from good [21,22,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,34,36,37], to fair [20,25,33,35], and to poor [23,38]. Overall, the studies lost points for internal validity (confounding—selection bias), due to issues aimed at randomized clinical trials and intervention.

One of the studies [35] did not provide any data regarding the representativeness of the entire population from which participants invited or prepared to participate in the study. In most of studies, it was unable to be determined if the subjects asked to participate in the study were representative of the entire population from which they were recruited, or this information was not provided. Notably, only two of the studies reported a power analysis [28,31].

3.3. Studies Characteristics

A descriptive synthesis of the records included is presented in Table 3, where summary information with reference to authors and years of publication was provided. Then, the terminologies used in defining and evaluating the study variables were examined. Identification and characterization of groups (with hypertension, control, or other diseases or conditions) were extracted, including sample size, age, and other provided details (Table 4). Aspects related to the adopted intervention program, configuration, duration, and intervention procedures were also included. Finally, the assessed outcomes were extracted, and the main results were organized and described.

Table 3.

Assessment of methodological quality.

Table 4.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies and outcomes extracted.

From the total records included in the qualitative synthesis, only five of them were specifically addressed to examine participants diagnosed with hypertension [23,25,26,30,33]. On the other hand, most of the studies dealt with cardiac rehabilitation subjects [20,21,22,27,28,29,34,35], while four included participants with coronary conditions [24,31,32,36]. Finally, the study of Hong et al. [38] included older adults in the community, and the study of Myers et al. [37] involved elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients. Two of the included records used a three-parallel group design to investigate the influence of different procedures, involving a control group [26,32].

The most common duration for an intervention program was a twelve-week period [19,23,26,27,28,31,32,34,36]. Duration ranged from a six-week minimum period [31] to a twelve-month intervention program [30,34]. Most of the studies had a follow-up analysis beyond the intervention period [23,24,25,27,28,29,32,33,34,35,36].

3.4. Exercise Monitoring and Prescription

The exercise monitoring systems included the use of heart rate monitors [20,28,29,32,35,37], heart rate reserve [21,28,35,37], respiratory rate [28,29], perceived exertion using the Borg scale [21,28,37], and energy consumption [31]. Physical activity patterns were also assessed using Fitbit activity trackers [27,38], accelerometry [25,29], and pedometers [23,26,37]. Supervised exercise training controlled by tele-electrocardiogram (ECG) recording was also used in several studies [21,22,28,29,36]. In the Hwang et al. [24] study, the telerehabilitation program was delivered via a synchronous videoconferencing platform, enabling the physiotherapist to watch participants performing the exercises and provide real-time feedback and modification, as required. Only in a few cases was exercise monitoring not available or reported [30,33,34].

Interaction between patients’ and the multidisciplinary team responsible for delivering the intervention program, in particular the physical activity or exercise prescription component, was commonly assured via a bespoke smartphone and web application or website, telephone, short message service (SMS), or e-mail. On the other hand, self-registration of training data was normally carried out later using a monitoring center capable of receiving and storing patients’ data.

Regarding exercise prescription, it was not available in only one study [38]. In five studies [23,25,30,31,33], participants were instructed to perform physical activity according to general recommendations provided by various health-related organizations. In two of the studies [24,26], the authors reported individualized interventions based on current recommendations, with no further information being provided on how the exercise programs were customized for each participant. Most of the studies (n = 11) involved a personalized training prescription based on a previous physiological assessment, particularly following a cardiopulmonary exercise test. Interestingly, only one study [35] also included the assessment of muscle power and muscle strength to individualize the participant’s training sessions.

3.5. Outcomes and Results Regarding Hypertension and Blood Pressure Management

The contribution of physical activity, exercise or lifestyle changes in an intervention program showed significant improvements in blood pressure values in six of the studies [23,25,26,30,33,38]. After induction of the telemedicine system proposed by Okura et al. [23], SBP (135 ± 15.8 to 129 ± 13.4 mmHg; p = 0.001), morning (136 ± 16.1 to 132 ± 15.8 mmHg; p = 0.009) and evening blood pressure (131 ± 15.1 to 127 ± 14.0 mmHg) were significantly reduced. When divided according to the median of their daily walking steps, patients in the high daily walking steps group showed significant differences in morning SBP and morning diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and the evening SBP, while both groups had significantly reduced SBP. The implementation of an individualized structured program of increased activity [25] led to a significant decrease in office SBP (p = 0.004), office DBP (p = 0.001), and night-time pulse pressure automatic blood pressure monitoring after three months among resistant hypertension patients. According to the same study, only office DBP remained significantly lower after six months (p = 0.04). The expert-driven group in the Liu et al. [26] work demonstrated a significantly greater SBP reduction (mean difference: −7.5 mmHg) and pulse pressure (−4.6 mmHg) when compared to the control group, with no significant differences between the user and expert-driven groups being observed. The magnitude of SBP from baseline at four and twelve months in the Nolan et al. [30] study showed a significant greater reduction (−10.1 mmHg (−12.5, −7.6); p = 0.02) for the e-counseling group at twelve months, although a significant decrease was verified in both groups for SBP and DBP. In the same work, pulse pressure reduction was also significant in a greater degree for the e-counseling at four (−4.5 mmHg (−6.2, −2.8); p = 0.004) and twelve months (−5.2 r (−6.9, −3.5); p = 0.04). Across all participants of the Hong et al. [38] study, and regardless of the Fitbit usage, SBP and DBP were, on average, 6.5 mmHg (p < 0.04) and 3.6 mmHg lower. Interestingly, the analysis at three months highlighted a borderline significant trend only for DBP (–2.2 (–4.5 to 0.0); p = 0.05) among the internet-based intervention participants [33], while the results at the 12-month follow-up showed significant improvements in DBP (–1.8 (–0.2 to –3.3); p < 0.03) for all participants.

Two studies [29,31] compared the effectiveness of home-based programs vs. the traditional center-based programs and found no significant differences between the two groups for improvement in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. In two other studies [32,34], results for blood pressure even showed an increase, particularly for diastolic blood pressure with increasing time of follow-up. No effects on blood pressure were reported in nine of the results [20,21,22,24,27,28,35,36,37].

4. Discussion

This review aimed to explore the contribution and effectiveness of physical activity or exercise in an intervention program using telemedicine with hypertensive patients. Our results showed that intervention programs were generally effective, particularly in reducing systolic blood pressure. Nevertheless, these programs are based on general counseling and guidelines. A patient-oriented approach was not a common practice when prescribing exercise, unlike what was noted among patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation programs.

The role of exercise in the prevention and treatment of hypertension is well documented, and several guidelines and recommendations are available [5,6,39,40]. According to our results, individualized telemedicine intervention programs based on lifestyle changes and counselling, particularly considering variations in physical activity and exercise patterns [23,25,33], was enough to verify significant improvements in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. In these studies, increased physical activity levels were advised and monitored by simply using a pedometer or an accelerometer. Aerobic exercise was shown as an effective treatment for blood pressure improvement in hypertensive patients [13,41,42] Evidence suggests that the aerobic exercise performed at 65–75% heart rate reserve, 90–150 min/week [6], shows overall reductions in SBP of −4.1 mmHg and DBP of −2.2 mmHg; the blood pressure lowering effects of dynamic resistance (90–150 min per week, 50–80% one repetition maximum, six exercises, three sets per exercise, ten repetitions per set) were −3.7 mmHg and −2.7 mmHg for systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively [39]. When combined, the overall effects of aerobic training and resistance exercise are reductions of −5.5 mmHg and −4.1 mmHg. Therefore, it would be of great interest to include resistance training in the patients’ exercise program. Curiously, instructions in muscle strength exercises were only given in the Laustsen et al. [35] study, although muscle training was not telemonitored.

The emergence of new technologies and communication platforms has offered a wider range of possibilities to monitor hypertensive patients’ health and physical activity levels, allowing clinical care to be provided at a distance, improving the quality-of-care services by increasing accessibility and reducing potential delays, and finally, enhancing the patients’ satisfaction and overall engagement [14]. In this regard, our results showed no differences in blood pressure values between home-based and traditional center-based programs [29,31], which also suggests the potential beneficial effects of remote supervised exercise delivered by clinical exercise physiologists. Nevertheless, our overall results also stressed the transient nature of the differences in blood pressure arising from the increase in physical activity. For example, office SBP and DBP in the resistant hypertension group decreased significantly after three months, but after six months only office DBP remained significantly lower, while the 24-h BP changes after six months were similar [25]. On the contrary, when exposed to a long-term home-based exercise program, hypertensive patients showed the most remarkable decreases in SBP and DBP vs. baseline within the first six months of intervention, with significant changes observed even 16 months after for the exercise group [43]. A recent narrative review [44] addressed the benefits of hypertension telemonitoring and home-based physical training programs, highlighting the effectiveness of mobile health in the follow-up of hypertensive patients and assisting in the adherence and control of associated risk factors, such as physical inactivity and obesity.

The integration of exercise professionals in multidisciplinary teams can enhance contribution and long-term effectiveness of physical activity or exercise in an intervention program using telemedicine with hypertensive patients. According to Ruberti et al. [44], safety assessment in a home-based exercise intervention is crucial, and a careful evaluation of the electronic medical record, multidisciplinary consultations, and self-monitoring are important strategies to guarantee the intervention security and effectiveness. Still, no reference to exercise professionals is apparent in several reviews focusing on telemedicine interventions in hypertension management [13,45,46]. A comprehensive study including cardiorespiratory fitness, physical fitness levels, muscle function, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and health-related quality of life, compared the long-term effects of a 12-week home-based physical training intervention with telemonitoring guidance to a prolonged 12-week center-based cardiac rehabilitation intervention, showing no differences between the two program settings in exercise capacity and physical activity levels [32]. Notably, the same study revealed that after one year of follow up, patients maintained their exercise capacity and physical activity levels, whereas a small though significant increase was observed for diastolic blood pressure from baseline to three-month follow-up. The home-based group trained the first three sessions under the supervision of the research group for acquaintance with the telemonitoring system, after which patients received an individualized exercise prescription—exercise for at least 50 min a week (preferably 6 to 7 days/week) at an individually determined target heart rate zone corresponding to moderate intensity, i.e., 70–80% of heart rate reserve; and weekly feedback by phone or e-mail during the three-month intervention. A weekly basis communication was also used in the work of Liu et al. [26], where e-mails to the expert-driven group participants consisted of predetermined exercise and dietary goals. This study showed a greater SBP decrease than controls at follow-up (expert-driven vs. control: −7.5 mmHg, 95% CI, −12.5, −2.6, p = 0.01) among the expert-driven group participants.

A primary concern when delivering home-based exercise should be training monitoring and guarantee of proper testing procedures to customize training planning among hypertensive patients, especially by integrating physical exercise professionals alongside with healthcare professionals. Personalized exercise prescription and monitoring in cardiac rehabilitation patients were highlighted in the present work (e.g., training variables and data registration platforms). The use of a heart rate monitor, the assessment of physical activity patterns, or ECG were the most common monitoring systems in our study, focusing on the aerobic component. Although the benefits of aerobic training is consistent throughout literature, resistance training may raise more questions [39,42]. The dose–response relationship between resistance training and hypertension is still uncertain given the large spectrum of study participants characteristics and exercise interventions (type, intensity, volume, frequency, or progression). Thus, it is highly recommended to control these exercise variables by placing a greater focus on monitoring and assessing motor capacity [47]. For example, the rating of perceived exertion, repetitions in reserve, set-repetition best, autoregulatory progressive resistance exercise, and velocity-based training monitoring methods may provide a useful strategy to analyze an individuals’ daily readiness due to their autoregulatory nature when performed in a home-based basis. In this sense, exercise professionals’ play an important role in advising, guiding, instructing and customize training variables for each individual needs, emphasizing the creation of lifestyle habits that promote better health. Additionally, these professionals can help the adherence and maintenance of changes, given the transient effect verified in the current study, and also facilitating the interaction with individuals’ and their physical needs, besides being a cost-efficient care delivery strategy [24,26,29,32].

Limitations of the present study must be acknowledged, and these include the implementation of exercise interventions in individuals with different characteristics, particularly when cardiac rehabilitation patients were included, as they were on hypertensive medication, but other comorbidities were excluded, or different grades of hypertension were not taken into account. Moreover, the selected experimental design was experimental or observational, not being restricted to randomized controlled trials. Telemedicine represents a useful attempt to help deliver continuous, personalized and effective care to hypertensive patients and optimize their management by healthcare professionals and other care managers [14,48]. However, other e-health solutions and tools are available, like telehealth or m-health [45], although they were not considered as a search term at the present work at risk of making the search too broad.

5. Conclusions

The use of lifestyle interventions for the management of blood pressure are highly encouraged whatever the classification of blood pressure may be. According to this review, intervention programs using telemedicine with hypertensive patients based on general instructions and recommendations for exercise prescription and hypertension are generally effective in reducing blood pressure parameters. However, the adherence and maintenance to these physical exercise programs seems to be limited in time, resulting in transient benefits. We believe that the advising, guidance, instruction, and personalized training emphasizes the promotion of healthier lifestyle habits. As realized in patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation, a home-based customized exercise prescription can be safe and effective. Therefore, the use of multidisciplinary teams, including the potential benefits of integrating exercise professionals in exercise assessment, monitoring, and counseling in healthcare services could provide a more person-oriented approach and the long-term maintenance of a healthy lifestyle. Ultimately, it is intended that individuals are provided with self-regulation tools and sufficient autonomy for the control and management of modifiable variables on blood pressure, reducing the costs and burden over healthcare services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.-G. and S.V.; methodology, R.R.-G. and S.V.; software, R.R.-G., S.V. and R.S.; validation, R.R.-G., S.V. and R.S.; data collection, R.R.-G., S.V. and R.S.; statistical analysis and graphics, R.R.-G., S.V. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.-G. and S.V.; writing—review and editing, R.R.-G., S.V., R.S. and P.M.; visualization, R.R.-G., S.V., R.S. and P.M.; supervision, R.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully recognize the assistance of Marlene Rosa in the conceptualization stage of this work. The assistance of Roberta Frontini in the data organization is also appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Danaei, G.; Riley, L.M.; Paciorek, C.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Gregg, E.W.; Bennett, J.E.; Solomon, B.; Singleton, R.K.; et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, e13–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Galvez, B.G.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G.; Ordovas, J.M.; Ruilope, L.M.; Lucia, A. Lifestyle interventions for the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G.F.; Landolfo, C.; Niebauer, J.; Ozemek, C.; Arena, R.; Lavie, C.J. Promoting Physical Activity and Exercise: JACC Health Promotion Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1622–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwood, K.-J.; Watson, G.; O’Brien, J.; Williams, A.D. Consumer-Based Wearable Activity Trackers Increase Physical Activity Participation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, D.; Torlasco, C.; Ochoa, J.E.; Parati, G. Contribution of telemedicine and information technology to hypertension control. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 2020, 43, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.; Pinnock, H.; Paterson, M.; McKinstry, B. Implementing telemonitoring in primary care: Learning from a large qualitative dataset gathered during a series of studies. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffer-Hawlik, M.; Moran, A.; Zerihun, L.; Usseglio, J.; Cohn, J.; Gupta, R. Telemedicine interventions for hypertension management in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S. Connected Health in Hypertension Management. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, M.; Perez-Reviriego, A.A.; Castellano-Martinez, A.; Cascales-Poyatos, H.M. The Assessment of Myocardial Strain by Cardiac Imaging in Healthy Infants with Acute Bronchiolitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, P.; Jutai, J.W.; Strong, G.; Russell-Minda, E. Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: A systematic review. Can. J. Ophthalmol. J. Can. D’ophtalmologie 2008, 43, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, J.J.; Dinnes, J.; D’Amico, R.; Sowden, A.J.; Sakarovitch, C.; Song, F.; Petticrew, M.; Altman, D.G.; International Stroke Trial Collaborative, G.; European Carotid Surgery Trial Collaborative, G. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol. Assess. 2003, 7, iii-173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraal, J.J.; Peek, N.; Van den Akker-Van Marle, M.E.; Kemps, H.M.C. Effects of home-based training with telemonitoring guidance in low to moderate risk patients entering cardiac rehabilitation: Short-term results of the FIT@Home study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Zieliński, T.; Bodalski, R.; Rywik, T.; Dobraszkiewicz-Wasilewska, B.; Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Stepnowska, M.; Przybylski, A.; Browarek, A.; Szumowski, Ł.; et al. Home-based telemonitored Nordic walking training is well accepted, safe, effective and has high adherence among heart failure patients, including those with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: A randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 22, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Stepnowska, M.; Leszczyńska-Iwanicka, K.; Piotrowska, D.; Kowalska, M.; Tylka, J.; Piotrowski, W.; Piotrowicz, R. Quality of life in heart failure patients undergoing home-based telerehabilitation versus outpatient rehabilitation—A randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014, 14, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okura, T.; Enomoto, D.; Miyoshi, K.-i.; Nagao, T.; Kukida, M.; Tanino, A.; Pei, Z.; Higaki, J.; Uemura, H. The Importance of Walking for Control of Blood Pressure: Proof Using a Telemedicine System. Telemed. E-Health 2016, 22, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, R.; Bruning, J.; Morris, N.R.; Mandrusiak, A.; Russell, T. Home-based telerehabilitation is not inferior to a centre-based program in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomised trial. J. Physiother. 2017, 63, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, P.J.; Nowicki, M. Effect of the physical activity program on the treatment of resistant hypertension in primary care. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2018, 19, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Brooks, D.; Thomas, S.G.; Eysenbach, G.; Nolan, R.P. Effectiveness of User- and Expert-Driven Web-based Hypertension Programs: An RCT. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duscha, B.D.; Piner, L.W.; Patel, M.P.; Craig, K.P.; Brady, M.; McGarrah, R.W.; Chen, C.; Kraus, W.E. Effects of a 12-week mHealth program on peak VO2 and physical activity patterns after completing cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Am. Heart J. 2018, 199, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawstorn, J.C.; Gant, N.; Rolleston, A.; Whittaker, R.; Stewart, R.; Benatar, J.; Warren, I.; Meads, A.; Jiang, Y.; Maddison, R. End Users Want Alternative Intervention Delivery Models: Usability and Acceptability of the REMOTE-CR Exercise-Based Cardiac Telerehabilitation Program. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2373–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, R.; Rawstorn, J.C.; Stewart, R.A.H.; Benatar, J.; Whittaker, R.; Rolleston, A.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Moodie, M.; Warren, I.; et al. Effects and costs of real-time cardiac telerehabilitation: Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Heart 2019, 105, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, R.P.; Feldman, R.; Dawes, M.; Kaczorowski, J.; Lynn, H.; Barr, S.I.; MacPhail, C.; Thomas, S.; Goodman, J.; Eysenbach, G.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of E-Counseling for Hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e004420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Huang, B.; Xu, D.; Li, J.; Au, W.W. Innovative Application of a Home-Based and Remote Sensing Cardiac Rehabilitation Protocol in Chinese Patients After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Telemed. E-Health 2019, 25, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, A.; Claes, J.; Buys, R.; Azzawi, M.; Vanhees, L.; Cornelissen, V. Home-based exercise with telemonitoring guidance in patients with coronary artery disease: Does it improve long-term physical fitness? Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 27, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisón, J.F.; Palomar, G.; Mensorio, M.S.; Baños, R.M.; Cebolla-Martí, A.; Botella, C.; Benavent-Caballer, V.; Rodilla, E. Impact of a Web-Based Exercise and Nutritional Education Intervention in Patients Who Are Obese With Hypertension: Randomized Wait-List Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunde, P.; Bye, A.; Bergland, A.; Grimsmo, J.; Jarstad, E.; Nilsson, B.B. Long-term follow-up with a smartphone application improves exercise capacity post cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laustsen, S.; Oestergaard, L.G.; van Tulder, M.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Petersen, A.K. Telemonitored exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves physical capacity and health-related quality of life. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 26, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szalewska, D.; Główczyńska, R.; Piotrowicz, R.; Kowalik, I.; Pencina, M.J.; Opolski, G.; Zaręba, W.; Banach, M.; Orzechowski, P.; Pluta, S.; et al. An aetiology-based subanalysis of the Telerehabilitation in Heart Failure Patients (TELEREH-HF) trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Chan, K.; Chen, Y.; Lit, Y.; Patti, A.; Massaband, P.; Kiratli, B.J.; Tamura, M.; Chertow, G.M.; Rabkin, R. Effect of a Home-Based Exercise Program on Indices of Physical Function and Quality of Life in Elderly Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2021, 46, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Jakacic, A.N.; Sahoo, A.; Breyman, E.; Ukegbu, G.; Tabacof, L.; Sachs, D.; Migliaccio, J.; Phipps, C.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Use of Fitbit Technology Does Not Impact Health Biometrics in a Community of Older Adults. Telemed. E-Health 2021, 27, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, H.; Boardman, H.; Deiseroth, A.; Moholdt, T.; Simonenko, M.; Krankel, N.; Niebauer, J.; Tiberi, M.; Abreu, A.; Solberg, E.E.; et al. Personalized exercise prescription in the prevention and treatment of arterial hypertension: A Consensus Document from the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) and the ESC Council on Hypertension. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 29, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescatello, L.S.; Buchner, D.M.; Jakicic, J.M.; Powell, K.E.; Kraus, W.E.; Bloodgood, B.; Campbell, W.W.; Dietz, S.; Dipietro, L.; George, S.M.; et al. Physical Activity to Prevent and Treat Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Li, X.; Yan, P.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, K. The effectiveness of aerobic exercise for hypertensive population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019, 21, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco-Ledo, G.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G.; Ruilope, L.M.; Lucia, A. Exercise Reduces Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Patients With Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e018487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinatti, P.; Monteiro, W.D.; Oliveira, R.B. Long Term Home-Based Exercise is Effective to Reduce Blood Pressure in Low Income Brazilian Hypertensive Patients: A Controlled Trial. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 23, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruberti, O.M.; Yugar-Toledo, J.C.; Moreno, H.; Rodrigues, B. Hypertension telemonitoring and home-based physical training programs. Blood Press. 2021, 30, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omboni, S.; Caserini, M.; Coronetti, C. Telemedicine and M-Health in Hypertension Management: Technologies, Applications and Clinical Evidence. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 23, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Li, Y.; Chia, Y.C.; Cheng, H.M.; Minh, H.V.; Siddique, S.; Sogunuru, G.P.; Tay, J.C.; Teo, B.W.; Tsoi, K.; et al. Telemedicine in the management of hypertension: Evolving technological platforms for blood pressure telemonitoring. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Hornsby, W.G.; Stone, M.H. Training for Muscular Strength: Methods for Monitoring and Adjusting Training Intensity. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 2051–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S.; McManus, R.J.; Bosworth, H.B.; Chappell, L.C.; Green, B.B.; Kario, K.; Logan, A.G.; Magid, D.J.; McKinstry, B.; Margolis, K.L.; et al. Evidence and Recommendations on the Use of Telemedicine for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: An International Expert Position Paper. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1368–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).