Linguistic–Cultural Mediation in Asylum and Refugee Settings and Its Emotional Impact on Arabic–Spanish Interpreters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Theory of Emotions and the Possible Psychological Impact of the Interpreted Communicative Act

2. Research Questions and Objectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

- -

- General aspects: academic and professional profile.

- -

- Specific aspects: emotional impact of interpreting in asylum and refugee contexts.

- -

- Specific aspects: strategies adopted to mitigate the possible emotional impact.

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of Interpreting in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

4.2. Interpreting Techniques Used in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

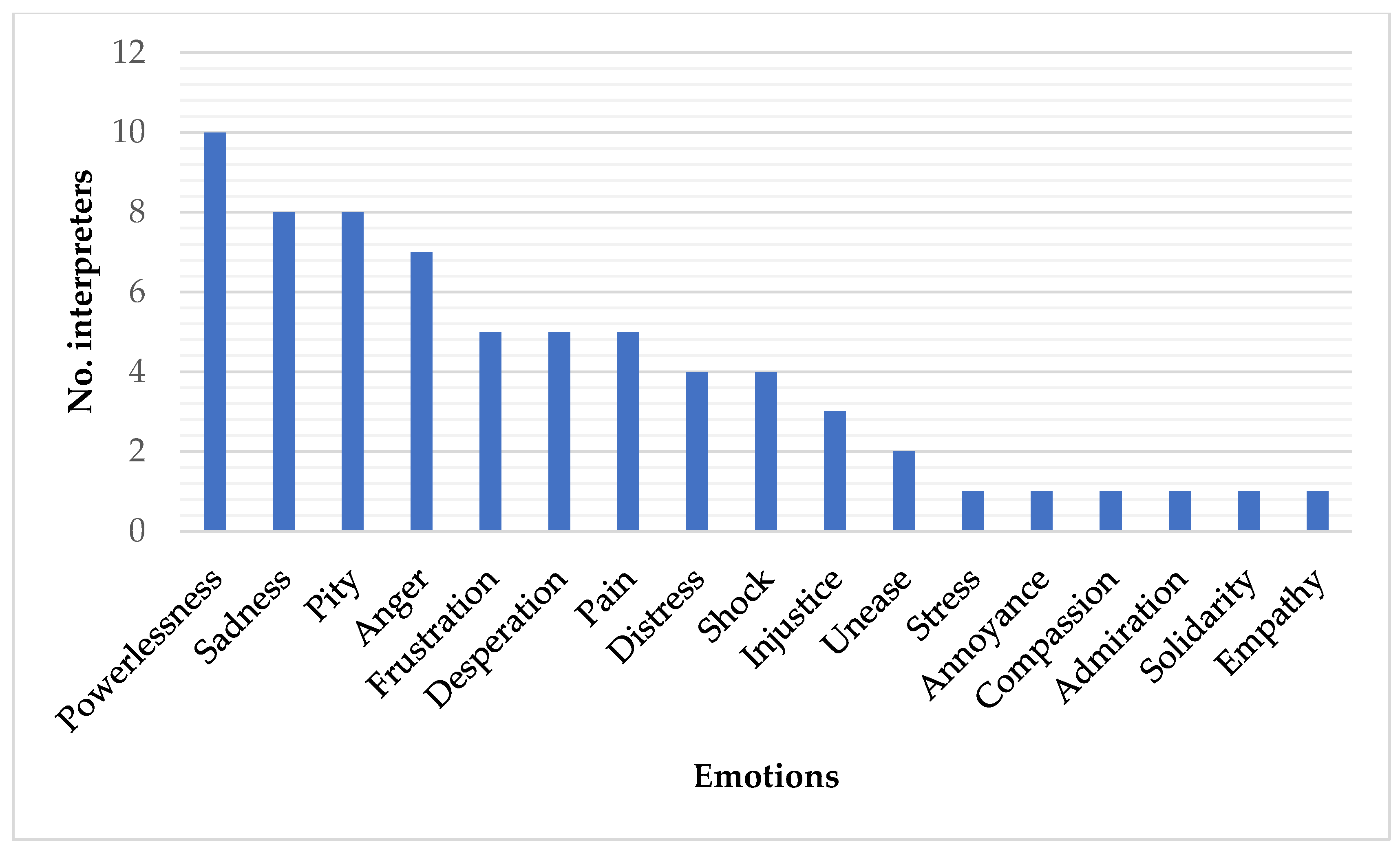

4.3. Emotional Impact of Interpreting in Contexts of Asylum and Refuge

4.4. Psychological Support for Interpreters in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

4.5. Perception of Overcoming Emotional Impact

- “I try to think that in life we all have painful stories depending on our contexts, that at the end of the day interpreting is my profession and I should do it to my best ability full stop. I mustn’t allow it to affect me”.

- “I mustn’t take that person’s side, and only concentrate on interpreting what he says”.

- “The strategies I employ go from trying to live a healthy life, in all aspects, talk to my loved ones about my unease (without going into detail about what happened in order to respect the privacy of the users), trying to put to what point my contribution reaches into perspective and not forgetting that at least through my efforts their right to express themselves and understand what’s being communicated to them is guaranteed, learning to disconnect and be aware of the line separating empathy from excessive involvement”.

- “It depends a lot on the subject being dealt with, but for example I try not to look the client in the eyes, I can sometimes get overwhelmed with the language of the eyes, so I choose not to use it to stay more neutral”.

- “Meditation and Yoga”.

- “I try and focus on the interpreting, that is, in the discourse, the vocabulary, transmitting the message correctly, etc.”.

- “Relaxation exercises, looking for pleasant distractions (music), calming the mind focusing on the message”.

- “Separating work from personal life”.

- “Putting the needs of the person who we’re interpreting first. To alleviate the subsequent feeling of sorrow, it helps to speak about what happened with someone with whom this is possible (to respect confidentiality) or in very general terms (and always protecting the privacy of the affected person) with someone you trust”.

- “There are worse things in life. I can’t take people’s problems home with me, I’ve got to limit myself to interpreting the best way possible. If I drift off course psychologically I won’t be able to keep helping these people”.

- “I try to think that my best contribution to them is to interpret in the best way possible, wish them luck and keep progressing in helping more people. Because of the way I am, I’m a very empathetic person, but I was able to achieve the balance of saying I love my job, I want to help these people and to do so I must try and control my emotions. Sometimes in the middle of an interpreting job, I repeat to myself in my mind: this is your job, don’t let it affect you, don’t let it affect you”.

- “Swallow and keep going, as easy and complicated as that. Hold back those emotions however you can, finish the job and then try not to think about it or clear your mind with another task”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Frequency of Interpreting and Interpreting Techniques Used in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

5.2. Emotional Impact of Interpreting in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

5.3. Psychological Support for Interpreters and Perception of Overcoming Emotional Impact in Asylum and Refugee Contexts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darwin, C. A biographical sketch of an infant. Mind 1877, 2, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals; J. Murra: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, S.S. Affect, Imagery, Consciousness (Vol. 1): The Positive Affects; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, S.S. Affects, Imagery, Consciousness (Vol. 2): The Negative Affects; Springer: Belin, Germany, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Izard, C.E. The Face of Emotion; Appleton: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gerver, D. Empirical studies of simultaneous interpretation: A review and a model. In Translation: Applications and Research; Brislin, R.W., Ed.; Gardner Press: New York, USA, 1976; pp. 165–207. [Google Scholar]

- Seleskovitch, D. Language and cognition. In Language Interpretation and Communication; Gerver, D., Sinaiko, H.W., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Chernov, G. Semantic aspects of psycholinguistics research in simultaneous interpretation. Lang. Speech 1979, 22, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gile, D. Basic Concepts and Modes for Interpreter and Translator Training; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gile, D. Conference Interpreting as a Cognitive Management Problem. In Cognitive Processes in Translation and Interpreting; Danks, J., Shreve, G.M., Fountain, S.B., McBeath, M., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo, K.; Napier, J. Evaluating emotional stability as a predictor of interpreter competence and aptitude for interpreting. Interpreting 2011, 13, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpal, P. Linguistic and Psychological Indicators of Stress in Simultaneous Interpreting. Ph.D. Thesis, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez Olalla, J.F. Impacto psicológico. El Estrés: Causas, Consecuencias y Soluciones: Intérprete de Conferencias Frente a Intérprete en Los Servicios Públicos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Alcalá, Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2013. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Garcés, C. El impacto psicológico y emocional en los intérpretes y traductores en los servicios públicos. Un factor a tener en cuenta. Quad. Rev. Traducción 2006, 13, 141–154. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Baistow, K. The Emotional and Psychological Impact of Community Interpreting; Babelea: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mahyub Rayaa, B. La interpretación simultánea árabe-español y sus peculiaridades: Docencia y profesión. Estudio piloto. In Quality in Interpreting: Widening the Scope; García Becerra, O., Pradas Macías, E.M., Barranco-Droege, R., Eds.; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2013; pp. 337–358. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Mahyub Rayaa, B.; Sánchez Ramos, N. La mediación interlingüística e intercultural con menores refugiados: El caso del programa “Vacaciones en paz”. Dirasat Hum. Soc. Sci. 2020, 47, 63–75. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Mahyub Rayaa, B. Arabic-Spanish simultaneous interpreting: Training and professional practice. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Translation; Hanna, S., El-Farahaty, H., Khalifaet, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 350–365. [Google Scholar]

- León Pinilla, R. La presencia de la interpretación en contextos de asilo y refugio; ¿realidad o ficción? In Panorama de la Traducción y la Interpretación en Los Servicios Públicos Españoles: Una Década de Cambios, Retos y Oportunidades; Foulquié Rubio, A.I., Vargas Urpi, M., Fernández Pérez, M., Eds.; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2018; pp. 203–220. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Estevan, E. Interpretación en contextos de asilo y refugio: Conflictos éticos en la práctica. Una lucha hacia el bienestar. In Superando límites en Traducción e Interpretación en los Servicios Públicos; Valero-Garcés, C., Ed.; Universidad de Alcalá: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2017; pp. 92–98. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- León Pinilla, R.; Jordá-Mathiasen, E.; Prado-Gascó, V. La interpretación en el contexto de los refugiados: Valoración por los agentes implicados. Sendebar 2016, 27, 25–49. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pöllabauer, S. Interpreting in asylum proceedings. In The Routeledge Handbook of Interpreting; Mikkelson, H., Jourdenais, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 202–216. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Herráez, J.M. Interpretar Para la Justicia; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2011. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Blasco Mayor, M.J.; Pozo Triviño, M. La interpretación judicial en España en un momento de cambio. MonTI Monogr. Traducción Interpret. 2015, 7, 9–40. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piqueras Rodríguez, J.A.; Ramos Linares, V.; Martínez González, A.E.; Oblitas Guadalupe, L.A. Emociones negativas y su impacto en la salud mental y física. Suma Psicológica 2009, 16, 85–112. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Emotion in the Human Face; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 96, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; APA: Richmond, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Vindel, A.; Miguel-Tobal, J.J. Emociones y salud. Ansiedad Y Estrés 2001, 7, 111–121. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Steinman, L. Elaborate interactions between the immune and nervous systems. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency). Handbook for Interpreters in Asylum Procedures. UNHCR. 2017. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/dach/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/AUT_Handbook-Asylum-Interpreting_en.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021). (In Spanish).

- Lazarus, R.S.; Lazarus, B.N. Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla, M.; Rodríguez, I.; González, G. El estrés como amenaza y como reto: Un análisis de su relación. Cienc. Trab. 2009, 32, 96–101. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Oster, H. Facial expresssions of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1979, 30, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyatos, F. Nonverbal Communication Across Disciplines (Vol. 1, 2 y 3); John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso, M.S. El estrés crónico y la Terapia Cognitiva Centrada en Mindfulness: Una nueva dimensión en psiconeuroinmunología. Persona 2010, 13, 11–29. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, S.; Yalom, I.D. Guía Breve de Psicoterapia de Grupo; Pai Dós: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Mahyub Rayaa, B. Vaciado de respuestas de la Encuesta Sobre el Impacto Emocional de la Interpretación Español-Árabe en Contextos de Asilo y Refugio. Figshare. Dataset. In Spanish. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13313231.v2 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

| Academic Level | Area of Speciality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation and Interpreting | Arabic Philology | Hispanic Philology | Others | |

| Degree | 4 | - | - | Law: 1 Social work: 1 |

| Professional Master’s Degree (+Degree.) | 12 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ph.D. (+Degree and Master’s) | 4 | - | - | |

| Language/Interpreters | Arabic | Spanish | French | English | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 9 interpreters | 14 | - | - | Berber: 1 |

| B | 12 (dialectal in 1 case) | 19 | 1 | 2 | - |

| C | - | 1 | 9 | 8 | Portuguese: 1 German: 1 |

| Frequency | Daily | A Number of Times a Week | A Number of Times a Month | A Number of Times a Year | Occasionally (e.g., During Immigration Emergencies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. interpreters | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Interpreting Technique Used | No. Interpreters |

|---|---|

| Liaison in situ | 17 |

| Liaison telephone | 7 |

| Consecutive (one-directional and with note taking) | 2 |

| Sight translation | 2 |

| Whispered (chuchotage) | 1 |

| Duration | No. Interpreters |

|---|---|

| No further than the act I interpreted | 2 |

| Almost the entire following day | 3 |

| Days afterwards | 5 |

| Weeks | 4 |

| Months | 1 |

| Years | 2 |

| Other… | |

| At the beginning more than now It keeps repeating | 4 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahyub-Rayaa, B.; Baya-Essayahi, M.-L. Linguistic–Cultural Mediation in Asylum and Refugee Settings and Its Emotional Impact on Arabic–Spanish Interpreters. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1280-1291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040093

Mahyub-Rayaa B, Baya-Essayahi M-L. Linguistic–Cultural Mediation in Asylum and Refugee Settings and Its Emotional Impact on Arabic–Spanish Interpreters. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(4):1280-1291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahyub-Rayaa, Bachir, and Moulay-Lahssan Baya-Essayahi. 2021. "Linguistic–Cultural Mediation in Asylum and Refugee Settings and Its Emotional Impact on Arabic–Spanish Interpreters" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11, no. 4: 1280-1291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040093

APA StyleMahyub-Rayaa, B., & Baya-Essayahi, M.-L. (2021). Linguistic–Cultural Mediation in Asylum and Refugee Settings and Its Emotional Impact on Arabic–Spanish Interpreters. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1280-1291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040093