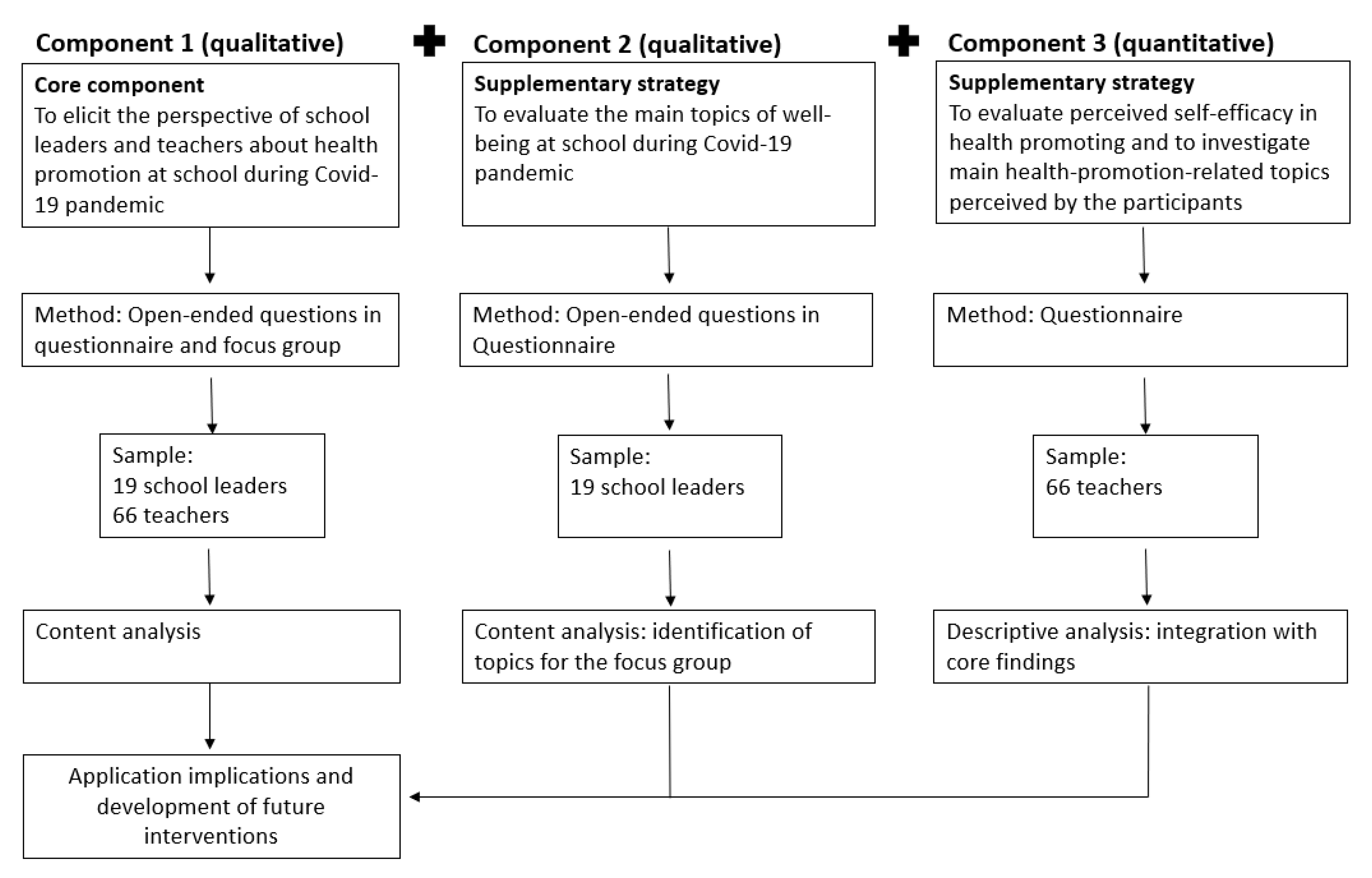

3.1. School Leaders: A Specific Viewpoint

Among school leaders, the creation of a network and exchange of information and best practices emerged as essential needs. These needs originated not only from the desire to continue the debate, but also from the value and uniqueness of the space the school leaders were offered: for the first time they found a space and a time to interact with each other among peers, where bureaucratic duties gave way to sharing of thoughts about the management of the schools, in the crucial period that started in March 2020, without forgetting the issues of health promotion. This time of discussion, in the form of a focus group, was highly valued by all participants.; the goal was to create an opportunity for reflection on practices, exchange and sharing of point of views, appreciation of what has been carried out so far and innovation and production of new ideas.

All these objectives were widely recognized and appreciated by the participants. The exchange of practices and thoughts has satisfied the need for sharing and debate in an open and dialogic atmosphere of exchange, also favored by the different professional experiences of each participant. Thanks to this dialogue, school leaders were able to emphasize the presence of many resources and recognize the great ability of innovation and adaptation that the schools showed in recent months.

A first goal of the meeting among school leaders was to share some educational premises and explore these issues taking into consideration both the learning and health dimensions. Secondly, the participants wanted to identify specific needs and difficulties in promoting each area. The meeting was therefore intended to be an opportunity to reflect on practices, to exchange and share thoughts, to enhance what had been carried out so far and to innovate and produce new ideas. For each theme presented below, a series of practices collected during the focus group were proposed. However, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of taking into consideration the context in which one operates. What may appear useful and functional for one school may, for several factors, be difficult to apply in another.

3.1.1. Promoting Civic Participation and Educability

Regarding the subject matter of the group work, it emerged how the participants considered civic participation and educability from different points of view.

A first topic of interest was education in being citizens, in respecting rules and in knowing and respecting the Constitution. Education to civic participation goes beyond individual teaching and represented the backbone that everyone in the school must deal with, together with the local community. The promotion of citizenship, in fact, concerns the entire life cycle and not only the school age. The participants then discussed the meaning of promoting citizenship nowadays. The theme of respect for the rules and shared responsibility within the entire educating community emerged. The promotion of civic participation and educability passes through the collaboration between teachers and school staff, which must be constantly cultivated. In addition, citizenship and educability are closely linked to the social context, the network of the local communities and the families. It is necessary to invest and seek a pact of trust with them, for the co-construction of an educational alliance.

“From my perspective, it is important for us as school leaders to ask ourselves who is skilled at educating today, what is educability. In my opinion education in being a citizen, in respecting the rules and in knowing and respecting the Constitution.” (School leader, group 1).

“It represents the backbone that all subjects within the school must deal with, together with the local community.” (School leader, group 1).

However, the participants emphasized that relationships, especially with families, were not always easy. Which needs and difficulties can we identify within these issues? The Families, the local community and the schools need to recognize themselves as an educating community, within a shared responsibility and pact. It also emerged the need of children for spaces for signification and sharing about what is happening, where dialogue and listening play a central role.

“The promotion of citizenship and educability passes through teamwork with teachers and school staff, with the network of the local communities and families, through the co-construction of an educational pact.” (School leader, group 1).

The good practices mentioned in the meeting are four: the link with the, the bond between community and local services, collective action of the teaching staff and teaching for skills. The first has the objective of maintaining contact between the school manager and the students to build shared responsibility and to understand the real needs of the students; it consists periodic meetings between the school manager and the students to build alliances, to define and apply procedures.

The second practice is aimed at maintaining and fostering a rich collaboration with local entities, structuring shared projects, even in the current situation in which it is more complex to allow external actors to attend school or students to go to other spaces. It consists in the organization of weekly meetings, mostly at a distance, between the school manager, local organizations and associations.

The third aims to promote collective action, fostering teamwork, changing the image of the school manager as a manager and commander working autonomously and alone. It consists in sharing a pedagogical and educational project with all school staff, both teaching and non-teaching, through an organizational consultancy model and meetings focused on sharing thoughts and exploring topics related to learning and health, defining common priorities and working on motivation.

The four practice aims to motivate teachers and school staff in competence-based teaching. It consists in identifying an external supervisor with whom to carry out meetings with school staff in small groups. The presence of an external guide to help identify work priorities is essential to have more serenity and awareness in transmitting active learning to students.

3.1.2. Learning and Active Methodologies

The participants in the working group defined learning as a dynamic theoretical, practical and experiential process that places the student at the center, as a unique individual. Active methodologies were defined as teaching strategies that put the student at the center of their own learning process. After a fruitful discussion, the group agreed that learning and active methodologies do not coincide, in an absolute way, with the curricular content.

“Learning is a dynamic theoretical, practical, and experiential process that places the student at the center, as a unique individual. Unfortunately, in recent months this issue has taken a back seat due to the need to limit COVID infections.” (School leader, group 2).

“In my opinion active methodologies as teaching strategies that place the student at the center of their own learning process.” (School leader, group 2)

The participants discussed the need to return as soon as possible to talk about learning, a topic that has taken a back seat in the recent months due to bureaucracy and focus on other aspects related to the COVID-19 emergency. They affirmed that learning should be one of the priorities for a school leader but, in recent months, they have found themselves performing unexpected tasks and actions such as measuring the size of classrooms and desks.

Participants brought out (or expressed) the need to motivate and increase the teachers’ interest in active ways of teaching that consider students as protagonists and that overcome the vision of sectorial learning by discipline. This change, however, is hindered by the environment and the society that acts in a logic of “everything and now”: many teachers often feel compelled to stick to the teaching programs, as sometimes requested also by parents, neglecting the importance of teaching by competence. Distance learning has made it more difficult to promote experiential modes of learning, even if it led to several profitable results.

“Our students are and should be more and more the protagonists of their own learning: during distance learning and lockdown they have demonstrated this, creating video research, photo albums, and other works supported by an excellent use of technology. in all this, the students have been at the center of the learning process.” (School leader, group 2).

Three best practices emerged from the discussion within this working group. The first, called “island desks”, had two goals, namely promoting collaborative work practices among students and between teachers and class groups, maintaining physical distance, and increasing the sense of autonomy, skills and responsibility, as well as learning through active methodologies. Moreover, it aimed to promote the inclusion of students with fragility. This practice consisted in arranging the desks in islands, i.e., “groups” of three. The students were seated facing the center of the group, sometimes with their backs to the teacher; every day a contact person for the working group was appointed, having the responsibility of communicating with the teacher and transmitting information and organizational tasks also towards the other two companions Within this organization students with fragility assumed the same responsibilities, sharing and collaboration as the others. The second practice, called agora, ensured the opportunity of meeting and exchange between students on different topics and promoted student participation and empowerment. This practice was based on the organization of common spaces as an agora/piazza, dedicated to a discussion between students through the placement of signs and the definition of spaces. In addition, students were co-protagonists and co-responsible in the cleaning and maintenance of these spaces. Finally, the third practice discussed within the thematic group was called “improvement goal” and was aimed to bring the student and his family to the center of the school’s attention; to define an educational pact of co-responsibility that included an individual goal for each student; to encourage an active role of the student in his educational path. During the first 2 months of the school year, teachers and students worked on identifying a personal improvement goal for each student.

This goal could be described, identified and pursued during the year. A tutor figure was identified among the teachers, to accompany the pupil and support them in achieving their personal goal. The students were invited to the usual interviews with families at the beginning of the year and all those involved signed the educational pact of co-responsibility, which also included the goal chosen by the student.

3.1.3. Sociality and Movement

What emerged is how the participants considered sociality as a mutual recognition, a way of being in a relationship with others, with a verbal and non-verbal communication system, that conveys the approval or disapproval of the interlocutor. For boys and girls, it meant making friends, recognizing one’s own emotions and expressing them, both in words and with gestures. Non-verbal emotional expression (facial expressions, hugging), for health prevention’s reasons, was currently limited, but the group shared the idea that if sociality meant being in a relationship, then it was possible to find new ways to do so, building new ways to recognize the emotions of others and expressing one’s own.

“It is mutual recognition; it is a way of being in relationship with others, accompanied by a system of verbal and nonverbal communication that contributes to convey the interlocutor’s approval or disapproval.” (School leader, group 3).

“In my opinion sociality means forming bonds and making connections.” (School leader, group 3).

“Sociality means being in a relationship and then it is possible to find new ways to do so, building new ways to recognize others’ emotions and expressing your own.” (School leader, group 3).

Sociality and movement today seem to be in contrast, in contrast with how they were conceived and experienced within the school context in the past. Nonetheless, the present situation presents itself as an opportunity to learn proper sociability, understood by the group as:

“Learning to be together with greater respect for others, for their sphere and their space.” (school leaders, group 3).

The participants discussed the fact that often the contact that children sought so much risked to degenerate into pushing behavior and disrespectful attitudes. The new procedures established due to the pandemic allowed students to experience new forms of cohabitation more respectfully. For example, in the canteen, the context became quieter and more suitable to enjoy the mealtime and promote sociability.

The need for non-verbal communication emerged in a transversal way. For a teacher, having the face covered by a mask was limiting because it was not possible to fully convey recognition, approval and emotional state. In the past, the teacher would greet boys and girls with a smile or at least with an expressive facial expression, but now this was not possible; we wonder which implications this may have and how to build a new style of communication. This lack is felt most strongly in front of students with special educational needs, considering that non-verbal communication is an indispensable mean of social interaction and the fatigue of the present moment.

“In front of a child with special educational needs, I pull down my mask and smile, but I don’t do that with other children”; “How do you reject a hug from them?”; “How do you put the instructions into practice with them?” (School leaders, group 3).

It is necessary to redefine what is meant by movement in this emergency phase, identifying all the contact forms still possible, despite the need to avoid the spread of COVID-19. Families were perceived by leaders as needing more assistance from the school, more focused on learning issues and on fears of future school closures, instead of focusing on the socialization aspects in the school context.

In parents, as well as in teachers, it was observed the need to have informal communicative exchanges.

“Before the pandemic there were more opportunities for teachers and parents to meet each other and the school staff.; now meetings are only scheduled on Meet, the space with families is only virtual and necessarily scheduled.” (School leader, group 3).

One of the best practices identified within the working group, called “movement and territory” was aimed at ensuring opportunities of movement using the spaces in the surrounding area. It consisted of the use of local community spaces, such as municipal parks or other surrounding areas. Another good practice was to foster students’ responsibility and involvement in school organization, with the purpose of caring for the school spaces. Finally, an experimented good practice consisted in finding new forms of sociability, through the research and implementation of new forms of non-verbal communication. For example, the usefulness of using the body to concretize the distance to be maintained between students (e.g., by extending the arms) and to find new gestures and codes of communication (e.g., replace the hug with a common gesture of raising their arms at the same time) has emerged.

3.1.4. Fragility

The concept of fragility emerged across the board in the different groups that addressed the topics described above. The group agreed in defining fragility as valuing uniqueness, on several levels.

“Fragility means an appreciation of the uniqueness of each student, family or teacher.” (School leader).

The themes of fragility and inclusion emerged as a priority in each group and in relation to the different themes. However, it is important to recognize the different forms of fragility through an appreciation of the uniqueness of each student, family or teacher. Which needs and difficulties have emerged in this regard? The first need emerged was how to identify and recognize its different forms. The importance of paying attention to situations in which physical distance could represent an additional difficulty emerged. Therefore, it was considered important to create spaces for meeting in person with families with fragilities, adopting the appropriate health precautions. In some cases, the need for a cultural mediator for a fruitful dialogue with parents could be useful.

A further need concerned the showing of facial expressions to children with special educational needs, as a vehicle for communication; in this case some managers have expressed the usefulness of being able to remove the mask, while maintaining distance, to address directly to a student with special needs.in a situation of fragility.

“It happens to me, to meet a child with special educational needs in the hallway and pull down my mask, so they can see my smile as I greet them. It’s not an attitude that strictly adheres to prevention regulations, but it’s an act of empathy and closeness that I believe is unparalleled towards a student’s fragility.” (School leader, group 4).

The promotion of citizenship and educability also passed through the recognition of the fragility of teachers, students, school administrators, families and the local community. An educating community was considered as a community that enhanced the uniqueness and diversity of each member. Therefore, the need emerged to listen to and recognize the different situations, to co-construct ways of meeting, teaching and protection.

The theme of fragility was placed at the center of attention when it came to learning and active methodologies.

“I strongly believe that open-ended competency-based instruction for all students should always be favored in order to include students and families with fragility.” (School leader, group 4).

Some schools have been active in these terms also through the concretization of practices, welcoming the need to stimulate the students’ creativity and curiosity, by changing settings within the classrooms. One of the best practices identified within the working group, aimed at facilitating the inclusion of students with special educational needs and detecting and learning about situations of fragility. This practice, called reception of students, consisted of a meeting in co-presence with the teachers. This reduced the teaching time for the first few weeks but increased the resources for the management of specific needs, while waiting for the arrival of dedicated staff. An additional good practice shared within the group concerned emotions and nonverbal communications. The goal was to find new channels to express what, due to the use of masks and physical distancing, it was not possible to express through non-verbal communication. It was undoubtedly a path of recognition of emotions and appreciation of the importance of verbalization.

Finally, a good practice related to learning and technology was also implemented, with a focus on fragility. Its objectives were to promote concrete learning by focusing on knowledge and attention to the single student, to promote practical skills, to detect new interests, to break down language and social barriers and, by promoting through the practice of concreteness a greater inclusion of vulnerable students and attention to inequalities, to limit the phenomena of school drop-out.

These goals were pursued using concrete, experiential, practice-based learning modalities based on technological tools (e.g., video, robotics, platforms) and by creating ad hoc training paths for teachers to ensure the implementation of the educational programs.

These activities were particularly useful in schools with populations with a greater social and cultural fragility. In addition, students with fragility could work, overcoming limitations and educational barriers.

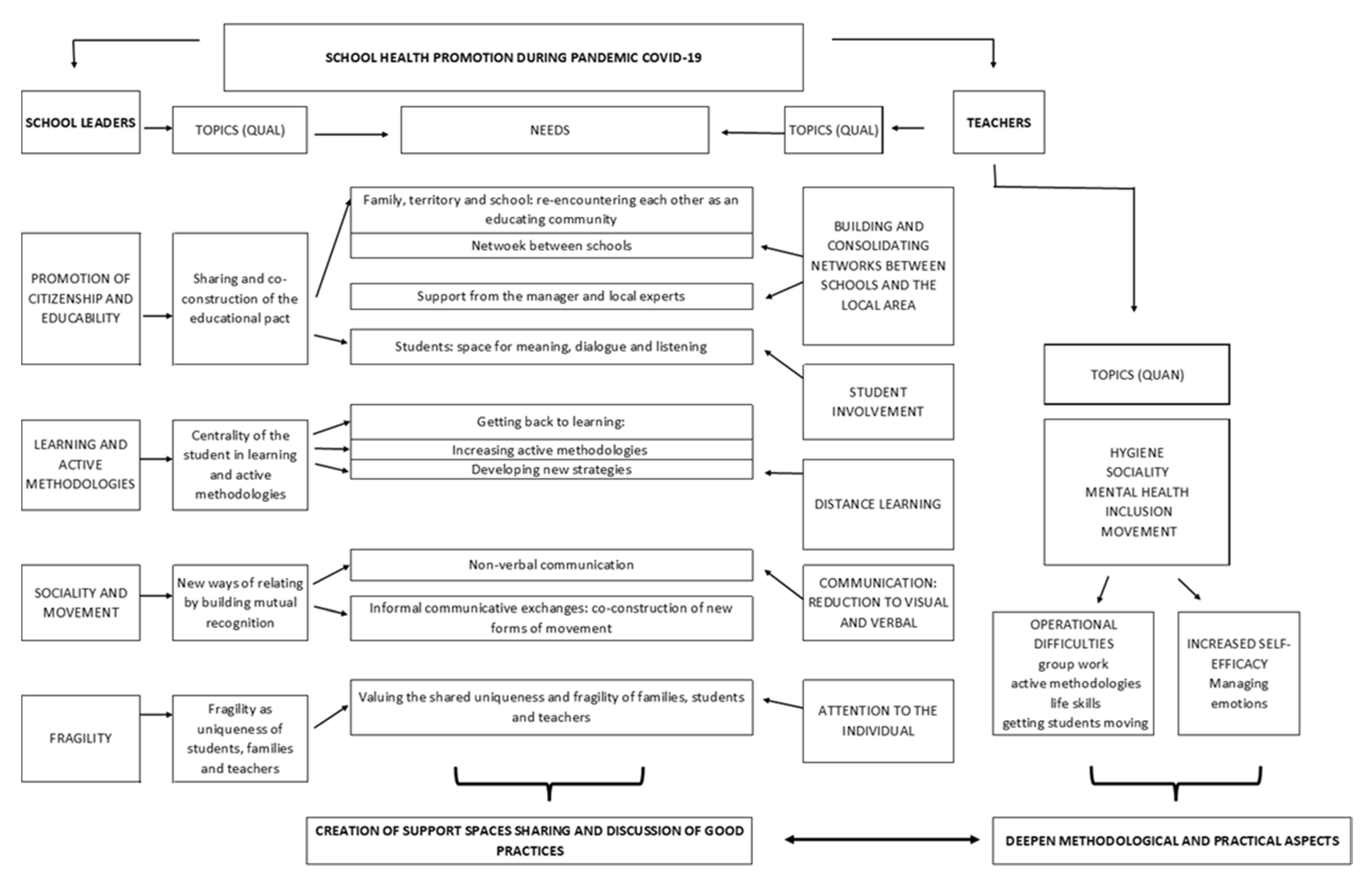

3.2. Teachers

3.2.1. Perceptions of Health Promotion

The analysis of the answers to the questionnaire from teachers at all school levels, showed a lack of physical interaction opportunities; as a result, communication between students and teachers was reduced to the visual-verbal level only. This kind of communicative exchange is perceived as inadequate to promote optimal and effective interventions.

“The difficulties are related to all the physical limitations caused by the health emergency, specifically the restriction in the use of space and materials, in the impossibility of sharing, the need to stay away from each other and the inability to interact face-to-face.” (T. Primary school).

“In person: The lack of adequately large spaces for respecting interpersonal distancing. At a distance: Time. Frequent login-logout procedures between lessons have halved the number of teaching hours.” (T. middle school).

“The greatest difficulty is the lack of an unstructured space in which the young people can express their hardships, challenges and discomforts, as well as the positive aspects and any positive experiences linked to the pandemic and to the physical distancing that we are all experiencing.” (T. high school).

Teachers in both middle and high schools reported difficulties related to DAD: in particular, technical problems (e.g., internet connection), the fatigue of extended screen time, the lack of time due to the switch to online teaching, the pressure caused by tight teaching programs and the risk of isolation of the most vulnerable subjects, who often could not participate in all remote activities. In the lower secondary schools, the lack of a space for emotional sharing of the difficulties linked to COVID and the difficulty of working in the classroom environment, the impossibility of engaging in socialization games or teamwork were also reported.

“The lack of direct contact with students, like it happens during DAD, makes it impossible to perceive and understand their emotions and their interests, expressed also with facial or body language. Distance cancels empathy.” (T. middle school).

Despite the above-mentioned obstacles, the teachers at middle schools identified activities that engaged students through the creation of power point Canva, brochures, multimedia products, slogans, research paths and spaces for listening and emotional sharing as primary strategies for health promotion.

On the other hand, the teachers operating in the high schools preferred activities of discussion and debate starting from stimuli such as scientific material, brochures and multimedia products based on meetings and conferences with experts.

“[…] by asking the pupils to work on a product to share with others. It could be a Power-point, a brochure with Canva, any multimedia product that brings together their reflections and research. You could share stimulating videos to launch the activity and then invite to a reflection, first personal and then shared. If possible, we could work in small groups.” (T. middle school).

“Through listening to their moods, what they miss by not attending school, how they spend their days, how they manage to establish relationships at a distance. I also use tools such as a padlet, to give them the opportunity to write and share their emotions.” (T. middle school).

“Helping students to know/recognize/experience healthy lifestyles: -caring for one’s own body and mind by training and practicing appropriate physical-sportive activities; - caring for one’s diet, not only from a theoretical point of view; -reading articles/texts/documents and watching carefully chosen films/videos to promote/make one think about issues related to the pandemic and its consequences; -reinforcing life skills as a resource for coping with critical moments in everyday life.” (T. high school).

In order to improve health promotion at school during the pandemic crisis, the teachers of all schools highlighted as important and fundamental the support and creation of a sharing network with organizations outside the school: the Network of schools that promote health and/or local Institutions such as associations, social-health services, local authorities, etc.

A need to create spaces for discussion and sharing of good practices emerged, with a focus on developing a greater network between schools and colleagues from different institutes, to establish relationships of collaboration and sharing, as well as information and training meetings for teachers, students and families.

Secondary school teachers expressed, furthermore, the need to receive psychological support and more listening and emotional support from professionals.

Especially in the answers of the teachers of the middle and high schools, the necessity of a greater presence in schools of the local authorities emerged, in particular with the request for greater collaboration in taking charge of situations of fragility, in receiving operative and technical indications for the promotion of Life Skills and in sharing of material and practical tools.

The local community was therefore seen as a great source of collaboration and a fundamental presence.

“A shared platform where you can receive strategies, suggestions…” (T. Middle school).

“Being in a new and particularly difficult situation, I would expect ideas and material to engage the children and their families.” (T. Middle school).

“Meetings with experts or receiving strategies that a teacher can put in place for the students’ psycho-physical well-being.” (T. High school).

“Ideas and material for practical activities, at relational, educational and didactic level—also for pupils with BES, ADHD…” (T. Primary).

“Courses that help to cope with distress for teachers who, as “helping professionals”, do not have spaces dedicated to this, and have to face bigger and bigger challenges due to both the COVID emergency and the psycho-social conditions of families, which are more and more problematic and difficult to manage.” (T. Primary).

Figures that were in closer contact with the school, such as school leaders and parents, on the other hand, were perceived as present and often helpful. Teachers of all grades reported that they were already supported by their school leader and stressed the importance of receiving support, listening and motivation. More space for sharing and discussion should be created for parents in the middle school, instead.

“In my opinion, my head school leader is an understanding person and if I needed any kind of support, she would give it to me.” (T. Primary).

“The school leader head teacher has done her utmost to provide teachers and pupils with a psychologist, with whom we were able to talk when we returned in September. I hope that the head teacher will continue to give importance to the various aspects of health, safety and work.” (T. Primary).

“As I am also part of the management staff, I think it is difficult to ask for any other kind of support from our head teacher, at the moment. I think that my head teacher supports me, within the limits of the restrictions and safety regulations, in all the initiatives and experiences I have with my students.” (T. High school).

“Meetings with some frequency. The lockdown experience had also put a strain on parents who were happy to ask for an opportunity to talk and discuss with each other.” (T. Middle school).

“I have sometimes involved parents indirectly through interviews about health and I think it could also work at a distance. Perhaps, charts of the class data could be produced, with which to start a discussion.” (T. Middle school).

“Involving parents in meetings at a distance is easier than in person. Promoting actions that are certainly effective for everyone, that really reach everyone is another thing.” (T. Middle school).

3.2.2. Perceptions of Self-Efficacy

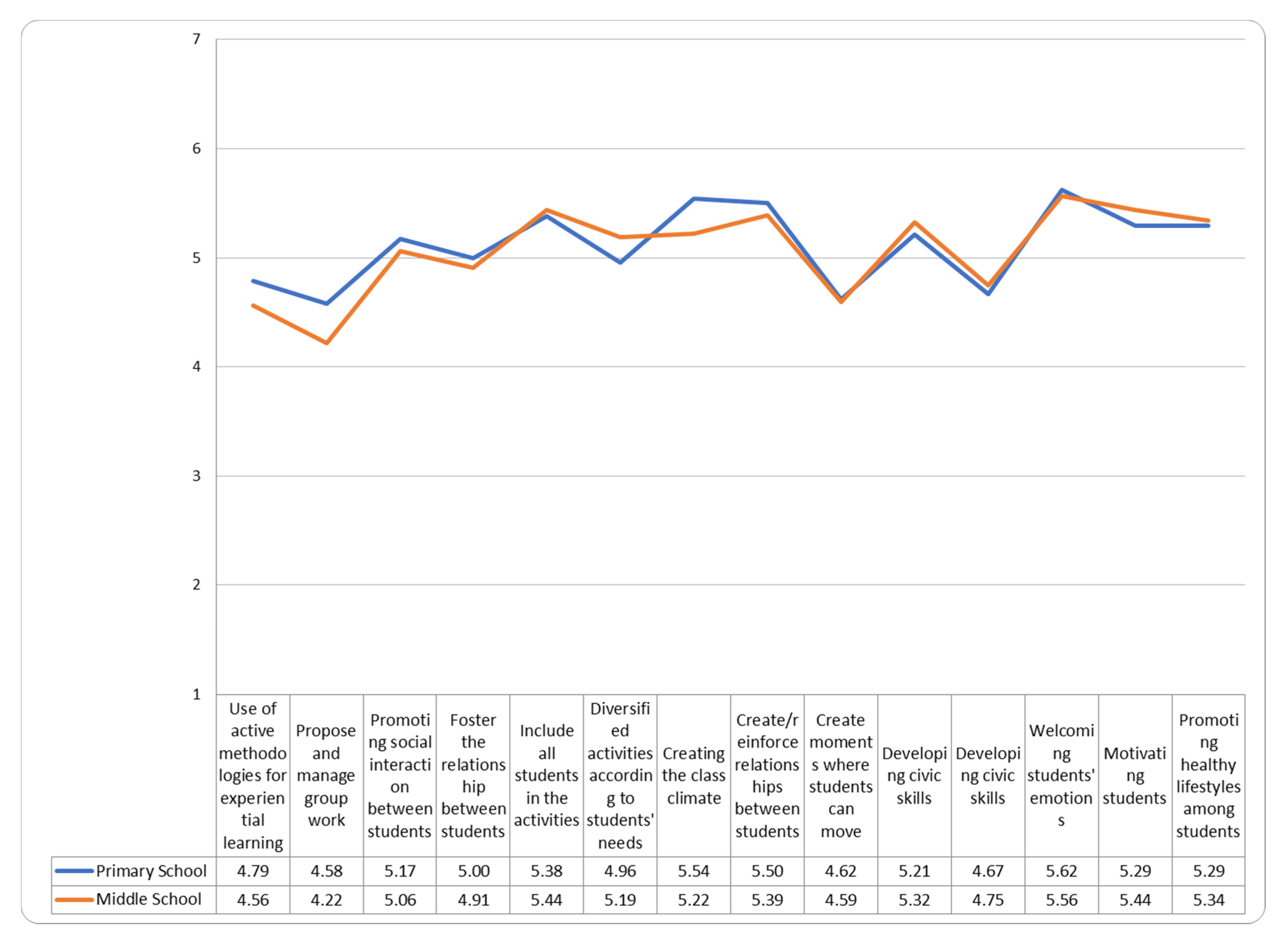

The teachers of primary and secondary schools showed a low to medium perception of self-efficacy in carrying out their profession during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. (

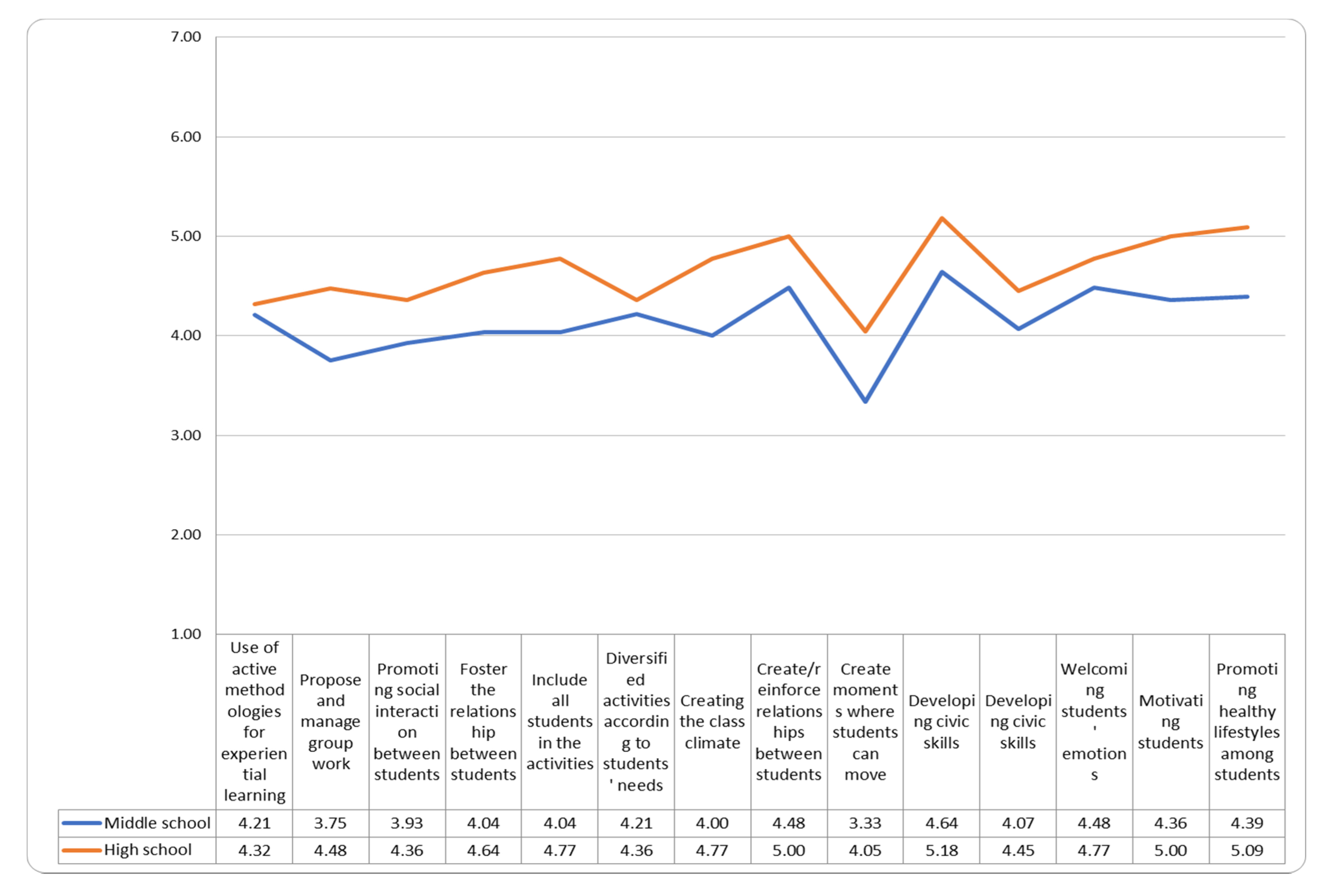

Figure 2). In particular, they felt less able to propose group work, promote physical exercise and strengthen the students’ life skills. In carrying out their professional practices at a distance, secondary school teachers expressed a perception of medium-low self-efficacy. In this case too, the activity in which they felt they had the most difficulty was the promotion of motor activity; those in which they felt most capable were creating and strengthening the bond between teachers and students, developing citizenship skills, motivating students and encouraging healthy lifestyles.

The high school teachers, compared to the middle school teachers, felt more able to face the challenges of their professional practice, in relation to health promotion, with a distance learning mode instead of face-to-face (see

Figure 3).

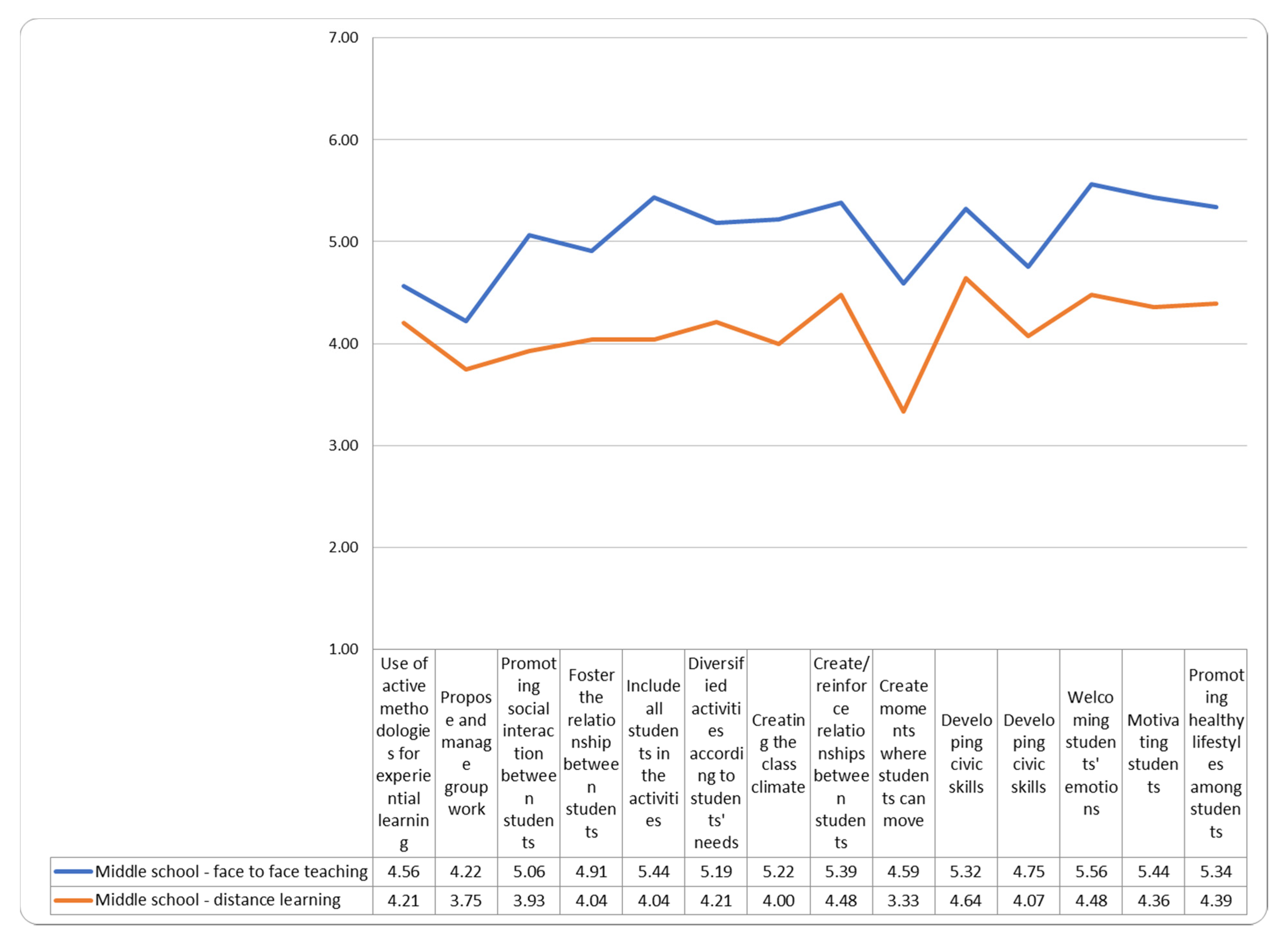

In particular, as we can observe from the graph, with face-to-face teaching they felt more effective in welcoming the students’ emotions, in better managing the inclusion of all the students during the activities and in creating and strengthening the bonds among the students.

However, the perception of self-efficacy detected was at medium-low levels especially with the remote learning (see

Figure 4).

Teachers were also presented with a number of health promotion topics and asked to indicate which of these topics would be most important in this particular historical period.

The elementary school teachers considered prevention/health promotion topics related to physical activity, mental health and sociality more important than addictions and hygiene in this period of pandemic crisis. The teachers working in the middle school considered important also the theme of bullying and cyberbullying, in addition to those already mentioned. Finally, the teachers operating in the high schools considered health promotion in the areas of mental health, sociality and physical activity as relevant. The topics of tobacco use, and other addictions were left out by all teachers, given the period of isolation and closures.