Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction: Mediation of Subjective Well-Being and Moderation of Forgiveness Climate in Health Care Sector

Abstract

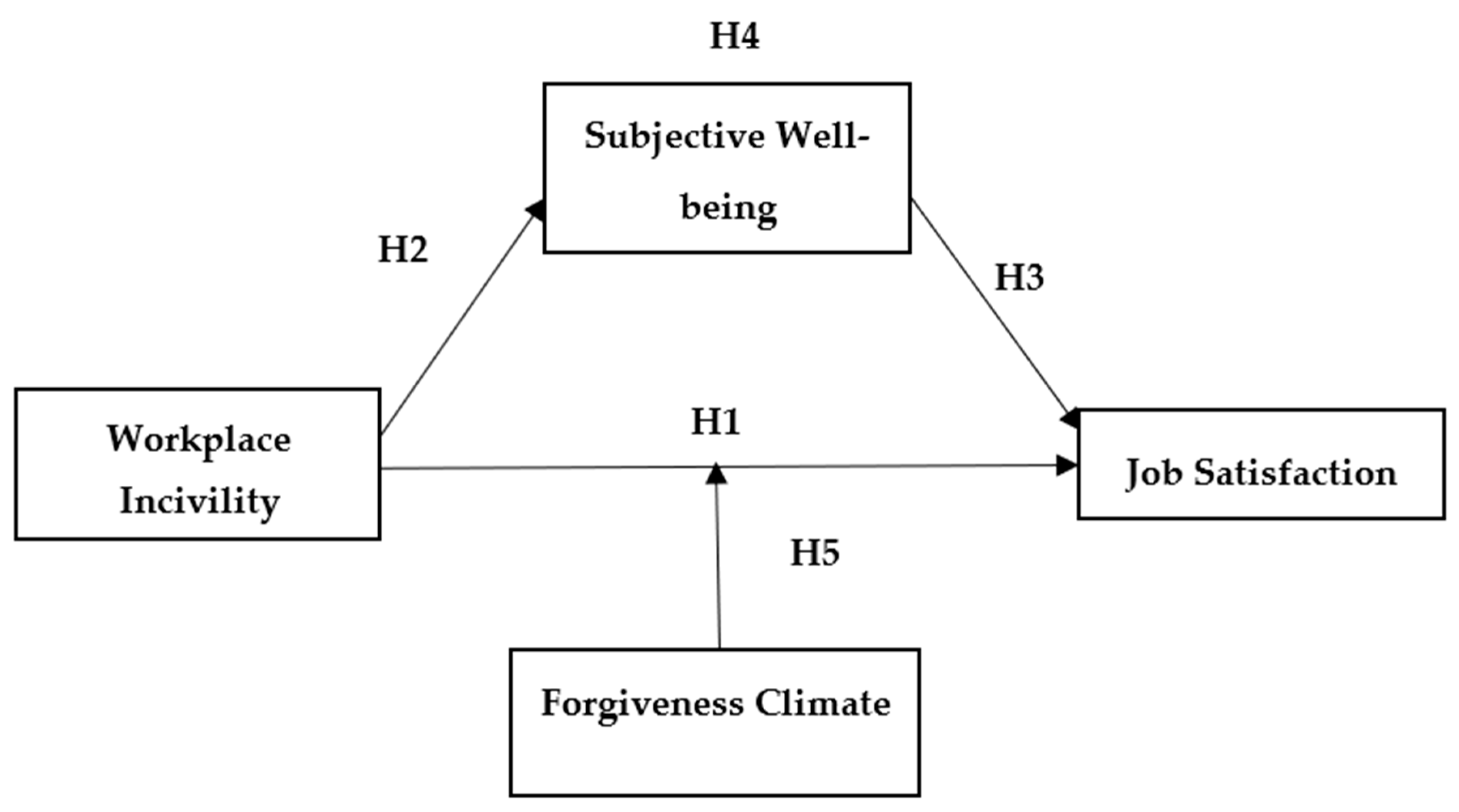

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Perspective

2.2. Workplace Incivility, Subjective Well-Being, and Job Satisfaction

2.3. Moderating Role of Forgiveness Climate between Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction

3. Methods

Study Instruments

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Construct Validity

4.3. Reliability and Correlation Coefficient

4.4. Direct, Indirect, and Conditional Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Study Limitations and Future Scholarly Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vagharseyyedin, S.A. Workplace incivility: A concept analysis. Contemp. Nurs. 2015, 50, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porath, C.; Pearson, C. The price of incivility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Vessey, J.A.; DeMarco, R.F.; Gaffney, D.A.; Budin, W. Bul lying of staff registered nurses in the workplace: A preliminary study for developing personal and organizational strategies for the transformation of hostile to healthy workplace environments. J. Prof. Nurs. 2009, 25, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Andrusyszyn, M.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S. Effects of workplace incivility and empowerment on newly-graduated nurses’ organizational commitment. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S. Impact of workplace mistreatment on patient safety risk and nurse-assessed patient outcomes. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2014, 44, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekici, D.; Beder, A. The effects of workplace bullying on physicians &nurses. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 31, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Nosko, A. Exposure to workplace bullying and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology: The role of protective psychological resources. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 23, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.A.; Gillespie, G.L.; Fisher, B.S.; Gormley, D.; Haynes, J.T. Psychological distress & workplace bullying among registered nurses. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2016, 21, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, A.; Christensen, K.B.; Hogh, A.; Rugulies, R.; Borg, V. One-year prospective study on the effect of workplace bullying on long-term sickness absence. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 19, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsky, C.A.; Fritz, C.; Hammer, L.B.; Black, A.E. Workplace incivility and employee sleep: The role of rumination and recovery experiences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ali, W.; Ameen, A.; Isaac, O.; Khalifa, G.S.A.; Shibami, A.H. The mediating effect of job happiness on the relationship between job satisfaction and employee performance and turnover intentions: A case study on the oil and gas industry in the United Arab Emirates. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yousef, D.A. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and attitudes toward organizational change: A study in the local government. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 40, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetio, A.P.; Yuniarsih, T.; Ahman, E. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior in state-owned banking. Univers. J. Manag. 2017, 5, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grobelna, A.; Sidorkiewicz, M.; Tokarz-Kocik, A. Job satisfaction among hotel employees: Analyzing selected antecedents and job outcomes. A case study from Poland. Argum. Oeconomica 2016, 2, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.M.M.; Yarmohammadian, M.H. A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2006, 19, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Tang, C.; Day, J.; Adler, H. Supervisor support and turnover in hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen, H.; Barmanpek, U. Fear of happiness & subjective well-being: Mediating role of gratitude. Turk. Stud. 2020, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, C.; Kinicki, A.J.; Tamkins, M.M. Organizational culture & climate. In Handbook of Psychology: I/O Psychology; Berman, W.C., Ilgen, D.R., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 12, pp. 565–593. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, R. Perceived forgiveness climate and punishment of ethical misconduct. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batik, M.V.; Bingol, T.Y.; Kodaz, A.F.; Hosoglu, R. Forgiveness and subjective happiness of university students. Int. J. High. Educ. 2017, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, S.; Neves, P. Forgiving is good for health and performance: How forgiveness helps individuals cope with the psychological contract breach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, Z.; Karim, J.; Din, S. Workplace incivility & counterproductive work behavior: Moderating role of emotional intelligence. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2013, 28, 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Giumetti, G.W.; Hatfield, A.L.; Scisco, J.L.; Schroeder, A.N.; Muth, E.R.; Kowalski, R.M. What a rude e-mail! Examining the differential effects of incivility versus support on mood, energy, engagement, and performance in an online context. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Khan, B.; Rafiq, Z.; Ahmed, A. Workplace incivility: Uncivil activities, antecedents, consequences, and level of incivility. Sci. Int. 2015, 27, 6307–6312. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.M.; Porath, C.L. On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2005, 19, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Kabat-Farr, D.; Magley, V.J.; Nelson, K. Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samma, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rasool, S.; Han, X.; Ali, S. Exploring the relationship between innovative work behavior, job anxiety, workplace ostracism, and workplace incivility: Empirical evidence from small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). Healthcare 2020, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Li, Z.; Luo, W. An identification-based model of workplace incivility and employee creativity: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 57, 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 34, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Abid, G.; Rana, K.S.; Ahmad, M. Extra-role performance of nurses in healthcare sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, C.H.; Kim, C. Impact of workplace incivility on compassion competence of Korean nurses: Moderating effect of psychological capital. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahri, A.S.; Qureshi, M.A.; Mallah, A.G. The negative effect of incivility on job satisfaction through emotional exhaustion moderated by resonant leadership. 3C Empres. Investig. Pensam. Crítico 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.M.I.; Thorsteinsson, E.; Loi, N.M. Workplace incivility and work outcomes: Cross-cultural comparison between Australian and Singaporean employees. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 59, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; Sage: Frankfurt, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Day, A.; Oore, D.G. The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; de Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, J.H.; Grandey, A.A. Customer incivility as a social stressor: The role of race and racial identity for service employees. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Patterns & profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 272. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-X.; Ding, G.-F.; Gu, X.-X. Job burnout and job performance in uncivilized behavior targets. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2014, 28, 535–540. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, C.C.; Koopman, J.; Gabriel, A.S.; Johnson, R.E. Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when &why incivility begets incivility. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Ahmed, S.; Elahi, N.S.; Ilyas, S. Antecedents and mechanism of employee well-being for social sustainability: A sequential mediation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.H.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Farooqi, S. Employee energy and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 40, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, K.; Abid, G.; Butt, T.H.; Ilyas, S.; Ahmed, S. Impact of ethical leadership and thriving at work on psychological well-being of employees: Mediating role of voice behaviour. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.U.; Khan, M.I.; Butt, T.H.; Abid, G.; Rehman, S. The balance between work and life for subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnette, M.D., Ed.; R & McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, K.; Lu, C.-S. Organizational motivation, employee job satisfaction and organizational performance. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2018, 3, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parvin, M.M.; Kabir, M.N. Factors affecting employee job satisfaction of pharmaceutical sector. Aust. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2011, 1, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas, S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ali, M.; Ali, W. Status quos are made to be broken: The roles of transformational leadership, job satisfaction, psychological empowerment, and voice behavior. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211006734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Lu, X.; Yu, Y. Supervisors’ ethical leadership and employee job satisfaction: A social cognitive perspective. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A. The mediating role of work atmosphere in the relationship between supervisor cooperation, career growth and job satisfaction. J. Work. Learn. 2019, 31, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Fayzullaev, A.K.U.; Dedahanov, A.T. Management characteristics as determinants of employee creativity: The mediating role of employee job satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maan, A.T.; Abid, G.; Butt, T.H.; Ashfaq, F.; Ahmed, S. Perceived organizational support and job satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of proactive personality and psychological empowerment. Futur. Bus. J. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Shaikh, S.; Asif, M.F.; Elah, N.S.; Anwar, A.; Butt, G.T.H. Influence of perceived organizational support on job satisfaction: Role of proactive personality and thriving. Int. J. Entrep. 2021, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: A social-cognitive view. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Lent, R.W. Test of a social cognitive model of work satisfaction in teachers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, V.; Johansson Seva, I.; Strandh, M. Subjective well-being &job satisfaction among self-employed® ular employees: Does personality matter differently? J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2016, 28, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational climate research: Achievements and the road ahead. In Handbook of Organizational Culture & Climate, 2nd ed.; Ashkanasy, N.M., Wilderom, C.P.M., Peterson, M.F., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Guchait, P.; Abbott, J.L.; Lee, C.K.; Back, K.J.; Manoharan, A. The influence of perceived forgiveness climate on service recovery performance: The mediating effect of psychological safety and organizational fairness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S. A Forgiving Workplace: An Investigation of Forgiveness Climate, Individual Differences and Workplace Outcomes; Louisiana Tech University: Ruston, LA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A.; Dawson, M. Perceived supervisor and coworker support for error management: Impact on perceived psychological safety and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchait, P.; Lanza-Abbott, J.; Madera, J.M.; Dawson, M. Should organizations be forgiving or unforgiving? A two-study replication of how forgiveness climate in hospitality organizations drives employee attitudes and behaviors. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.Y.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ilyas, S. Impact of perceived organizational support on work engagement: Mediating mechanism of thriving and flourishing. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.S. An investigation of forgiveness climate and workplace outcomes. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2011, 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whited, M.C.; Wheat, A.L.; Larkin, K.T. The influence of forgiveness & apology on cardiovascular reactivity and recovery in response to mental stress. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 33, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, L.; Friedman, P. Forgiveness, gratitude, and well-being: The mediating role of affect and beliefs. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables & measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Asghari, E.; Abdollahzadeh, F.; Ebrahimi, H.; Rahmani, A.; Vahidi, M. How to prevent workplace incivility? Nurses’ perspective. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2017, 22, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgins, M.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Workplace bullying and incivility: A systematic review of interventions. Int. J. Work. Health Manag. 2014, 7, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Fit Indices | Hypothesized Model | Single Factor |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN (chi-square) | 244.21 | 2988.83 |

| DF (Degree of freedom) | 129 | 135 |

| CMIN/DF (Relative chi-square) | 1.89 | 22.13 |

| IFI (Incremental fit index) | 0.97 | 0.44 |

| NFI (Normed fit index) | 0.95 | 0.43 |

| CFI (Comparative fit index) | 0.97 | 0.44 |

| RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| TLI (Tucker-Lewis fit index) | 0.97 | 0.37 |

| Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.72 | |||

| Workplace incivility | 0.89 | 0.54 | −0.21 | 0.73 | ||

| Subjective well-being | 0.86 | 0.55 | 0.32 | −0.15 | 0.74 | |

| Forgiveness climate | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.44 | −0.13 | 0.18 | 0.79 |

| Variables | α | WPI | SWB | JS | FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace incivility | 0.89 | - | |||

| Subjective well-being | 0.85 | −0.13 ** | - | ||

| Job satisfaction | 0.76 | −0.17 ** | 0.26 ** | - | |

| Forgiveness climate | 0.83 | −0.11 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.35 ** | - |

| Direct Effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses 1,2,3 | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | p | |

| H1: Workplace incivility-> Job Satisfaction | −0.46 | 0.10 | −0.656 | −0.284 | 0.000 | |

| H2: Workplace incivility-> subjective well-being | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.181 | −0.050 | 0.001 | |

| H3: Subjective well-being-> Job Satisfaction | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.084 | 0.198 | 0.000 | |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| Hypothesis 4 | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | p | Z |

| Workplace incivility-> subjective well-being -> Job Satisfaction | −0.016 | 0.01 | −0.031 | −0.006 | 0.005 | −2.777 |

| Interaction Effect | ||||||

| Hypothesis 5 | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | p | |

| Int_1 WPI × FC | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.056 | 0.152 | 0.000 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.S.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G. Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction: Mediation of Subjective Well-Being and Moderation of Forgiveness Climate in Health Care Sector. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1107-1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040082

Khan MS, Elahi NS, Abid G. Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction: Mediation of Subjective Well-Being and Moderation of Forgiveness Climate in Health Care Sector. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(4):1107-1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Safdar, Natasha Saman Elahi, and Ghulam Abid. 2021. "Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction: Mediation of Subjective Well-Being and Moderation of Forgiveness Climate in Health Care Sector" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11, no. 4: 1107-1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040082

APA StyleKhan, M. S., Elahi, N. S., & Abid, G. (2021). Workplace Incivility and Job Satisfaction: Mediation of Subjective Well-Being and Moderation of Forgiveness Climate in Health Care Sector. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1107-1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040082