Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Reduce Occupational Stress

1.2. Mindfulness-Based Interventions and Time Management

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

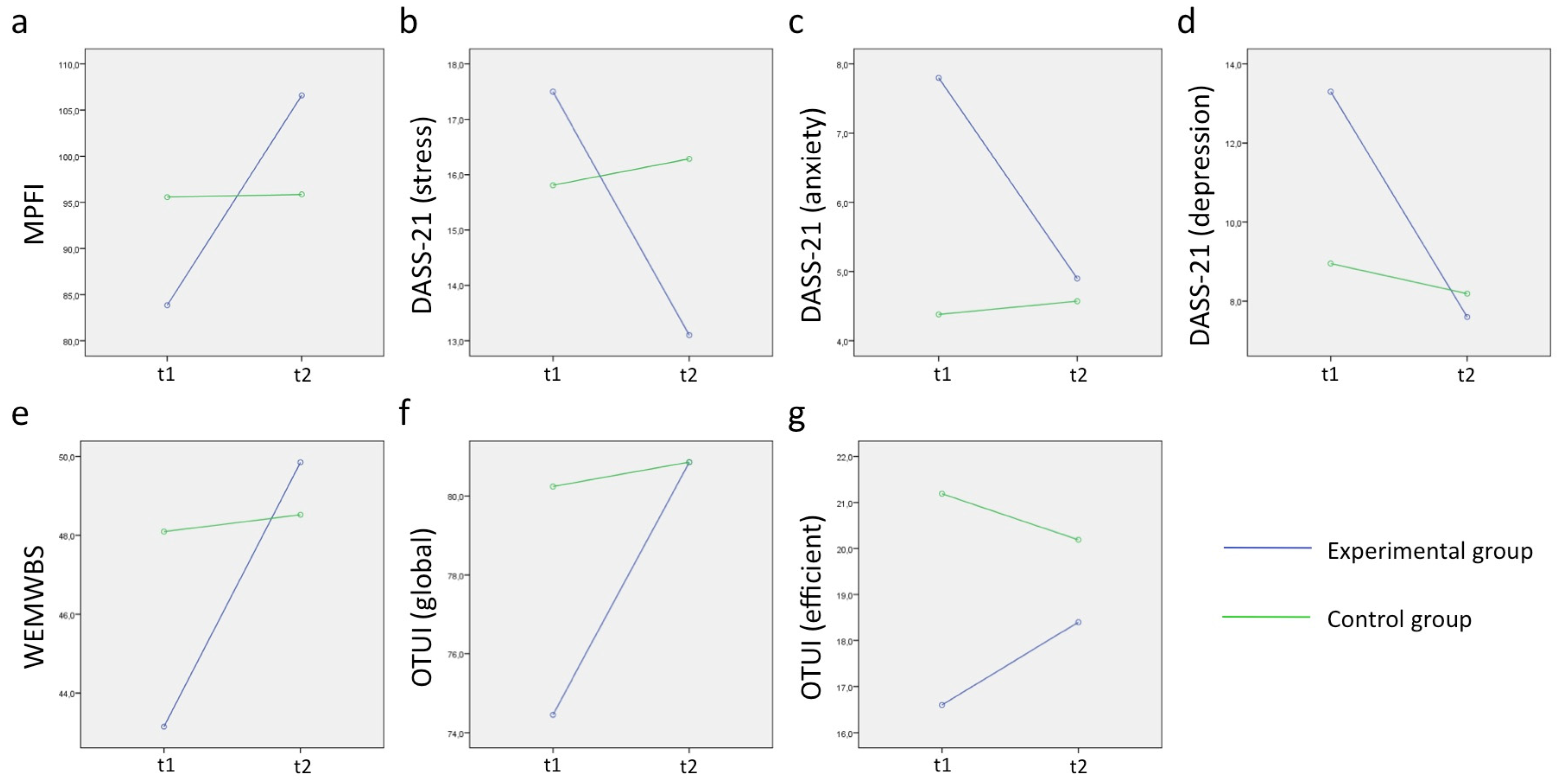

3.1. Effects of the Intervention on Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health and Well-Being

3.2. Effects of the Intervention on Time Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallup. Global Emotions Report. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/analytics/248906/gallup-global-emotions-report-2019.aspx (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Martin-Krumm, C.; Tarquinio, C.; Shaar, M. Psychologie positive et monde du travail: Entreprises, insitutions et associations. In Psychologie Positive en Environnement Professionnel; Martin-Krumm, C., Tarquinio, C., Shaar, M., Eds.; De Boeck: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Catano, V.; Francis, L.; Haines, T.; Kirpalani, H.; Shannon, H.; Stringer, B.; Lozanzki, L. Occupational stress in Canadian universities: A national survey. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, P.A.; Tytherleigh, M.Y.; Webb, C.; Cooper, C.L. Predictors of work performance among higher education employees: An examination using the ASSET Model of Stress. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Jones, F. ‘Running Up the Down Escalator’: Stressors and strains in UK academics. Qual. High. Educ. 2003, 9, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Jones, F. Effort-reward imbalance, over-commitment and work-life conflict: Testing an expanded model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.A.A.; Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K. Factors associated with occupational stress among university teachers in Pakistan and Finland. J. Educ. Health Community Psychol. 2017, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slišković, A.; Seršić, D. Work stress among university teachers: Gender and position differences. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2011, 62, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tytherleigh, M.Y.; Webb, C.; Cooper, C.L.; Ricketts, C. Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: A comparative study of all staff categories. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2005, 24, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, M.; Macaskill, A.; Reidy, L. Stress among UK academics: Identifying who copes best. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, M.; Martins, N. Developing a measurement instrument for coping with occupational stress in academia. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2019, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winefield, A.H.; Gillespie, N.; Stough, C.; Dua, J.; Hapuarachchi, J.; Boyd, C. Occupational stress in Australian university staff: Results from a national survey. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Jones, F. A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance, and wellbeing in UK academics. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2008, 17, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlind, G.; McAlpine, L. Academic Practice-How Is It Changing? University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, N.; Ungerer, L.M. Virtual teaching dispositions at a South African open distance learning university. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barkhuizen, N.; Rothmann, S. Occupational stress of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2008, 38, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.; Harper, S. Workplace stress and the student learning experience. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2006, 14, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport-SGEN-CFDT. Enquête sur les Conditions de Travail Dans la Recherche (Personnel BIATSS et ITA); Rapport-SGEN-CFDT: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beheshtifar, M.; Nazarian, R. Role of occupational stress in organizations. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2013, 4, 648–657. [Google Scholar]

- Boniwell, I.; Osin, E. Au dela de la gestion du temps: De l’usage du temps, de la performance et du bien-etre. In Psychologie Positive en Environnement Professionnel; Martin-Krumm, C., Tarquinio, C., Shaar, M., Eds.; De Boeck: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M.; Seeber, B.K. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, P.J.; Kyvik, S. Academic work from a comparative perspective: A survey of faculty working time across 13 countries. High. Educ. 2012, 63, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Where does the time go? An academic workload case study at an Australian university. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2019, 41, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Wray, S. Presenteeism in academic employees—Occupational and individual factors. Occup. Med. 2018, 68, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magelssen, S.; Lunderman, S.S. Tactical Slowness. Reversing the Cult of Speed in Higher Education: The Slow Movement in the Arts and Humanities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.A.; Rouch, J.-P. Le «je suis débordé» de l’enseignant-chercheur. Petite mécanique des pressions et ajustements temporels. Temporalités. Revue Sci. Soc. Hum. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Are academic workloads increasing? The post-war survey evidence in the UK. High. Educ. Q. 2010, 64, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winefield, T.; Boyd, C.; Saebel, J.; Pignato, S. Update on national university stress study. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2008, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkerman, M.; Pots, W.T.M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating mindfulness at work: An integrative review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: The Program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center; Delta: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, E.L.; Farb, N.A.; Goldin, P.R.; Fredrickson, B.L. Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.P.; Ryan, R.M.; Niemiec, C.P.; Legate, N.; Williams, G.C. Mindfulness, work climate, and psychological need satisfaction in employee well-being. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, R.; Alvarez-López, M.J.; Fagny, M.; Lemee, L.; Regnault, B.; Davidson, R.J.; Lutz, A.; Kaliman, P. Epigenetic clock analysis in long-term meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 85, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, R.; Fagny, M.; Cosin-Tomás, M.; Alvarez-López, M.; Lemee, L.; Regnault, B.; Davidson, R.; Lutz, A.; Kaliman, P. Differential DNA methylation in experienced meditators after an intensive day of mindfulness-based practice: Implications for immune-related pathways. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 84, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliman, P. Epigenetics and meditation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, A.S.; Brown, R.; Coe, C.L.; Zgierska, A.; Barrett, B. Mindfulness practice and stress following mindfulness-based stress reduction: Examining within-person and between-person associations with latent curve modeling. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Chaturvedi, S.; Ekkirala, S. The mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the relationship of mindfulness with turnover intentions and job performance. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, E.; McIver, S. Reducing stress and burnout in the public-sector work environment: A mindfulness meditation pilot study. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, H.K.; Laurent, S.M.; Lightcap, A.; Nelson, B.W. How situational mindfulness during conflict stress relates to well-being. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, M.A.; Gilbert, D.T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 2010, 330, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnlund, M.; Åström, E.; Carelli, M.G. Time perspective in late adulthood: Aging patterns in past, present and future dimensions, deviations from balance, and associations with subjective well-being. Timing Time Percept. 2017, 5, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. In Time Perspective Theory; Review, Research and Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 17–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rönnlund, M.; Åström, E.; Adolfsson, R.; Carelli, M.G. Perceived stress in adults aged 65 to 90: Relations to facets of time perspective and COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.; Boyd, J. The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, L.; Duncan, E.; Sutherland, F.; Abernethy, C.; Henry, C. Time perspective and correlates of wellbeing. Time Soc. 2008, 17, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, A.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Castellà, J.; Deví, J.; Soler, J. Does time perspective predict life satisfaction? A study including mindfulness as a measure of time experience in a sample of Catalan students. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnlund, M.; Koudriavtseva, A.; Germundsjö, L.; Eriksson, T.; Åström, E.; Carelli, M.G. Mindfulness promotes a more balanced time perspective: Correlational and intervention-based evidence. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1579–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seema, R.; Sircova, A. Mindfulness—A Time Perspective? Estonian Study. Balt. J. Psychol. 2013, 14, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarski, M.; Vowinckel, J.; Jankowski, K.S.; Zajenkowski, M. Mind the balance, be contented: Balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction. Personal Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Peter, J.; Gutina, O.; Otten, S.; Kohls, N.; Meissner, K. Individual differences in self-attributed mindfulness levels are related to the experience of time and cognitive self-control. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 64, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droit-Volet, S.; Heros, J. Time judgments as a function of mindfulness meditation, anxiety, and mindfulness awareness. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Otten, S.; Schötz, E.; Sarikaya, A.; Lehnen, H.; Jo, H.-G.; Kohls, N.; Schmidt, S.; Meissner, K. Subjective expansion of extended time-spans in experienced meditators. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennette, L.N.; Lin, P.S. Focusing on faculty stress. Transform. Dialogues 2019, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Minda, J.P. Mindful Leadership in the University. PsyarXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, T.; Holas, P. Effects of Brief Mindfulness Meditation on Attention Switching. Mindfulness 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.J. A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2010, 10, 125–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.; Luoma, J.; Bond, F.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Behaviour research and therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Mindfulness, self-compassion and psychological inflexibility mediate the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention in a sample of oncology nurses. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Z.V.; Teasdale, J.D.; Williams, J.M.G. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Theoretical Rationale and Empirical Status. In Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rolffs, J.L.; Rogge, R.D.; Wilson, K.G. Disentangling components of flexibility via the hexaflex model: Development and validation of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Assessment 2018, 25, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osin, E.; Boniwell, I. Does time management lead to optima; time use? Exploring the missing link between time perspective and well-being. Unpublished.

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaiko, H.W.; Brislin, R.W. Evaluating language translations: Experiments on three assessment methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 1973, 57, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Á/L. Erbaum Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.; Heerkens, Y.; Kuijer, W.; Van Der Heijden, B.; Engels, J. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on employees’ mental health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.-L.; Smoski, M.J.; Robins, C.J. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.-Y.; Hölzel, B.K.; Posner, M.I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, S.; Luong, M.T.; Schmidt, S.; Bauer, J. Students and Teachers Benefit from Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in a School-Embedded Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, M.; Gouda, S.; Bauer, J.; Schmidt, S. Exploring Mindfulness Benefits for Students and Teachers in Three German High Schools. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 2682–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Hamilton, J.; Schutte, N.S. The role of adherence in the effects of a mindfulness intervention for competitive athletes: Changes in mindfulness, flow, pessimism, and anxiety. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2016, 10, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacaille, J.; Sadikaj, G.; Nishioka, M.; Carrière, K.; Flanders, J.; Knäuper, B. Daily Mindful Responding Mediates the Effect of Meditation Practice on Stress and Mood: The Role of Practice Duration and Adherence. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layous, K.; Lyubomirsky, S. The how, why, what, when, and who of happiness. In Positive Emotion: Integrating the Light Sides and Dark Sides; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 473–495. [Google Scholar]

- Schumer, M.C.; Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Brief mindfulness training for negative affectivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, R.; Tessier, D.; Strub, L.; Gauchet, A.; Baeyens, C. Improving mental health and well-being through informal mindfulness practices: An intervention study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention Group | Control Group | The Whole Department * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (N = 41) | 20 | 21 | 184 |

| Female | 12 (0.6) | 13 (0.62) | 85 (0.46) |

| Male | 8 (0.4) | 8 (0.38) | 99 (0.54) |

| Permanent staff | 15 (0.75) | 16 (0.76) | 125 (0.68) |

| Short-term contracts | 5 (0.25) | 5 (0.24) | 59 (0.32) |

| Age (years) | 39.1 | 40.2 | 41.7 |

| Session | Opening | Guided Practices | Between-Session Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Presentation of the instructor; presentation of general guidelines (e.g., confidentiality…); presentation of each participant and their goals Introduction about stress at work (e.g., what is stress? How does it work?) | Mindful eating experience with a raisin Body scan | Daily body scan One mindful routine (e.g., teeth brushing) One mindful meal at work or at home |

| 2 | Short introduction meditation | Body scan Discussion about between-session practices Walking down the street exercise Sitting meditation | Pleasant events calendar (write down every evening the agreeable events of the day and their effects on thoughts, emotions, and sensations) Body scan 15 min sitting meditation One new mindful routine (e.g., walking to the workplace). |

| 3 | 30–40 min sitting meditation (with a focus on breath and body sensations) | Three minutes of mindful breathing (awareness, focus, and widening of attention) Mindful movements Mindful walking Calendar of unpleasant events | Sitting meditation for 15 min every other day Mindfulness movements Calendar of unpleasant events “Three minutes breathing space” three times a day |

| 4 | “See or hear” exercise (each participant chooses either to observe through the window what they see without judgment and welcoming their experience, or to listen to the current sounds) | 35 min of seated breathing Feedback and discussion on home practices Discussion about stress (perception, regulation strategies) Three minutes of mindful breathing Walking mindfully in a quiet area of the room | Sitting meditation every other day Yoga or mindful walking once a day Three minutes of “facing stress”, breathing each time stress rises in the workplace |

| 5 | Opening session with three minutes of breathing space | 20 min of sitting meditation incorporating visualization of a recent difficulty experienced at work (stress, tension) and reactions that emerge in the experience Feedback and discussion of practices done between sessions Three minutes of breathing space For 20 min, mindful dialogue exercise (mindful listening to a person telling a personal story of their choice) Reading of “The King and his Sons” Three minutes of mindful breathing | Sitting meditation “with difficulty” Three minutes of mindful breathing Three times a day |

| 6 | At the beginning of the session, three minutes of conscious breathing | 20 min of sitting meditation with difficulty Feedback and discussion about the between-session practice; Exercise of mindful dialogue on the theme “why am I doing this job?”; exercise on mood, alternative thoughts, and perspectives when occupational stress arises Three minutes of breathing space | Sitting meditation once a day Three minutes of mindful breathing and “coping with occupational stress” |

| 7 | Opening session with a meditation called “meditation without an object” (attention is first focused on the breath, then the participant is invited to abandon any observation of thoughts, emotions, or sensations, but simply to be present) | Feedback and discussion about inter-session practices Exercise “take care of myself and act”: elaboration of a list of activities for a typical day and ways to become more mindful during activities | 10 to 30 min of exercises by composing your own mindfulness program among all the practices already discussed |

| 8 | At the opening of the session, three minutes of conscious breathing | Body scan for 45 min Feedback and discussion on between-session practices Review of the whole program Discussion: how to maintain formal and informal practice after the program Three minutes of conscious breathing General feedback on the program by each participant; Closing of the program | Practices most useful for each participant |

| Questionnaires | Nature of Collected Data | Nb Items | Scale | Justification | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal data | Age, gender | 2 | - | Double-checking of t1 and t2 data pairing | |

| Multi-dimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory [63] | Psychological flexibility | 24 | 1–6 | Measuring one of the mechanisms of action of mindfulness based interventions on mental health and potentially time management change | 0.84 |

| DASS-21 [64] | Depression, anxiety, and stress | 21 | 0–3 | Measuring mental health | 0.82, 0.71 and 0.75 |

| Warwick–Edinburgh-Mental Well-Being Scale [65] | Subjective and psychological well-being | 14 | 1–5 | Measuring well-being | 0.87 |

| Optimal Time Use Inventory * [66] | Time management (self-congruent time, control over one’s time, balance of activities, efficient time, optimal time use index) | 25 | 1–5 | Measuring the different facets of time management | 0.82 |

| Intervention Group (N = 20) | Control Group (N = 21) | |

|---|---|---|

| MPFI (psychological flexibility) | 83.85 ** | 95.57 |

| DASS-21 (stress) | 17.50 ns | 15.81 |

| DASS-21 (anxiety) | 7.80 + | 4.38 |

| DASS-21 (depression) | 13.30 + | 8.95 |

| WEMWBS | 43.15 * | 48.09 |

| OTUI (global) | 74.45 ns | 80.24 |

| OTUI (self-congruent) | 24 + | 26.76 |

| OTUI (control) | 15 ns | 15.09 |

| OTUI (balance) | 18.85 ns | 17.19 |

| OTUI (efficient) | 16.6 ** | 21.19 |

| Stress | Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 24.4 | 70.7 | 48.8 |

| Mild | 41.5 | 4.9 | 19.5 |

| Moderate | 26.8 | 12.2 | 14.6 |

| Severe | 4.9 | 4.9 | 14.6 |

| Extremely severe | 2.4 | 7.3 | 2.4 |

| t1 | t2 | Time * Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int. Group (N = 20) | Cont. Group (N = 21) | Int. Group (N = 20) | Cont. Group (N = 21) | Interaction | η2 | |

| MPFI (psych. flexibility) | 83.85 | 95.57 | 106.60 | 95.86 | 25.49 *** | 0.39 |

| DASS-21 (stress) | 17.50 | 15.81 | 13.10 | 16.29 | 3.65 + | 0.09 |

| DASS-21 (anxiety) | 7.80 | 4.38 | 4.90 | 4.57 | 3.13 + | 0.07 |

| DASS-21 (depression) | 13.30 | 8.95 | 7.60 | 8.20 | 3.94 * | 0.09 |

| WEMWBS (well-being) | 43.15 | 48.09 | 49.85 | 48.52 | 5.82 * | 0.13 |

| OTUI (global) | 74.45 | 80.24 | 80.85 | 80.86 | 3.88 + | 0.09 |

| OTUI (self-congruent) | 24 | 26.76 | 25.60 | 26.62 | ns | - |

| OTUI (control) | 15 | 15.09 | 16.25 | 16.09 | ns | - |

| OTUI (balance) | 18.85 | 17.19 | 20.60 | 17.95 | ns | - |

| OTUI (efficient) | 16.60 | 21.19 | 18.40 | 20.19 | 6.97 * | 0.15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marais, G.A.B.; Lantheaume, S.; Fiault, R.; Shankland, R. Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 1035-1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040073

Marais GAB, Lantheaume S, Fiault R, Shankland R. Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2020; 10(4):1035-1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040073

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarais, Gabriel A. B., Sophie Lantheaume, Robin Fiault, and Rebecca Shankland. 2020. "Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 10, no. 4: 1035-1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040073

APA StyleMarais, G. A. B., Lantheaume, S., Fiault, R., & Shankland, R. (2020). Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(4), 1035-1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040073