Comparative Dynamics of Individual Ageing among the Investigative Type of Professionals Living in Russia and Russian Migrants to the EU Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

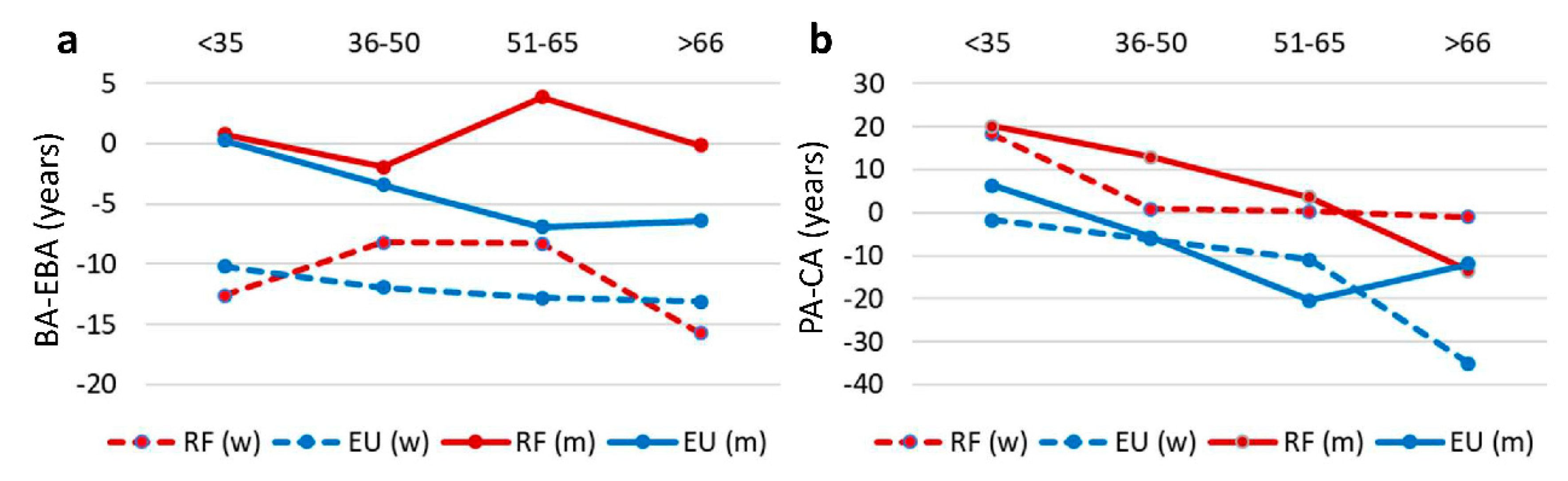

- The relative biological ageing index (biological age minus expected biological age, BA-EBA) allows us to evaluate how much an individual is older than their statistical age norm in regards to their health condition. Negative values indicate individual youthfulness of a person, and positive values indicate individual ageing respective of statistical norms. This is the main indicator used to assess the dynamics of relative ageing.

- Subjective psychological age (PA), developed in the laboratory of personality psychology of the Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (authors K.A. Abulkhanova and T.N. Berezina), based on the concept of personal organization of time [24,50] and on analysis of the subjective age of aged individuals [58,59]. The test subjects were asked to evaluate their age at the 100-point scale (from 0 to 100). The test subject may choose any number in this interval, corresponding to the self-esteem of their psychological age. Where 0 point is the psychological age of a new-born baby who has neither life experience nor personality, whose psyche is just beginning to develop. One hundred points is the psychological age of a person completing their course of life, who has achieved everything or will never progress from there, whose psyche is undergoing age-related degradation. The person chose any age in the range from 0 to 100, corresponding to their subjective sensation. We conducted a preliminary comparison of our methodology with the well-known methodology for assessing subjective time [24]. Similar to our 100-point scale was used as well. High levels of agreement were obtained on the total scale of Barack’s subjective age and on the assessment of subjective personality age according to our methodology (according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient). Therefore, for further analysis, we used the results obtained using our methodology.

- Index of relative psychological ageing (psychological age minus calendar age, PA-CA). Negative values indicate that a person is younger than their calendar age and is looking forward to the future. Positive values indicate that a person perceives themselves as more mature, wise, and successful than other people at this age.

- Statistical analysis. We tested normal distribution of age indicators. For the subjective age, biological age, expected biological age, and relative ageing index, the deviation from the normal distribution was not significant. Descriptive statistics were also calculated: average and standard deviation. To assess the influence of the country of residence on the indicators of relative psychological and relative biological ageing in men and women, Anova Factorial was conducted, as well as analysis of variance with the assessment of Fisher criteria (Fisher LSD). Anova Factorial analysis was applied to evaluate the significance of the influence of the following factors: the country of residence and gender, on relative ageing, in different age groups. We also calculated the interaction of these factors. For statistical analysis, we used the program Statistica -12 (SoftStat).

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Evaluation of Data and Methods Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Ethical Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foster, L. Active Ageing, Pensions and Retirement in the UK. J. Popul. Ageing 2018, 11, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäcken, J. Work stress among older employees in Germany: Effects on health and retirement age. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashman, J.J.; Schappert, S.M.; Santo, L. Emergency Department Visits Among Adults Aged 60 and Over: United States, 2014–2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2020, 367, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reus-Pons, M.; Kibele, E.U.B.; Janssen, F. Differences in healthy life expectancy between older migrants and non-migrants in three European countries over time. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosstat, R.F. Demographic Forecast until 2035; Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strizhitskaya, O. Aging in Russia. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Miche, M.; Brothers, A.F.; Barrett, A.E.; Diehl, M.; Montepare, J.M.; Wahl, H.W.; Wurm, S. The influence of subjective aging on health and longevity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorling, J.L.; Martin, C.K.; Redman, L.M. Calorie restriction for enhanced longevity: The role of novel dietary strategies in the present obesogenic environment. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosswell, A.D.; Suresh, M.; Puterman, E.; Gruenewald, T.L.; Lee, J.; Epel, E.S. Advancing Research on Psychosocial Stress and Aging with the Health and Retirement Study: Looking Back to Launch the Field Forward. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madore, C.; Yin, Z.; Leibowitz, J.; Butovsky, O. Microglia, Lifestyle Stress, and Neurodegeneration. Immunity 2020, 52, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chen, W.; McDermott, J.; Han, J.J. Molecular and phenotypic biomarkers of aging. F1000Res 2017, 6, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broskey, N.T.; Marlatt, K.L.; Most, J.; Erickson, M.L.; Irving, B.A.; Redman, L.M. The Panacea of Human Aging: Calorie Restriction Versus Exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2019, 47, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. Feeling too old? Consequences for subjective well-being. Longitudinal findings from the German Ageing Survey. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 90, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschoor, C.P.; Belsky, D.W.; Ma, J.; Cohen, A.A.; Griffith, L.E.; Raina, P. Comparing biological age estimates using domain-specific measures from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, C.M.; Hecksteden, A.; Morsch, A.; Zundler, J.; Wegmann, M.; Kratzsch, J.; Thiery, J.; Hohl, M.; Bittenbring, J.T.; Neumann, F.; et al. Differential effects of endurance, interval, and resistance training on telomerase activity and telomere length in a randomized, controlled study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo Carvalho, A.C.; Tavares Mendes, M.L.; da Silva Reis, M.C.; Santos, V.S.; Tanajura, D.M.; Martins-Filho, P.R.S. Telomere length and frailty in older adults—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 54, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, M.D.; Miranda-Dominguez, O.; Cohen, A.O.; Breiner, K.; Steinberg, L.; Bonnie, R.J.; Scott, E.S.; Taylor-Thompson, K.; Chein, J.; Fettich, K.C.; et al. At risk of being risky: The relationship between brain age under emotional states and risk preference. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 24, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Kynast, J.; Beyer, F.; Kharabian Masouleh, S.; Huntenburg, J.M.; Lampe, L.; Rahim, M.; Abraham, A.; Craddock, R.C.; et al. Predicting brain-age from multimodal imaging data captures cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 2017, 148, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.; Inoue, M.; Kajiya, F.; Inada, H.; Takasugi, S. Assessment of biological age by multiple regression analysis. J. Gerontol. 1975, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina, T.N.; Stelmakh, S.A.; Dergacheva, E.V. The effect of retirement stress on the biopsychological age in Russia and the Republic of Kazakhstan: A cross-cultural study. Psychologist 2019, 5, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N.; Fasbender, U.; North, M.S. Youthfuls, Matures, and Veterans: Subtyping Subjective Age in Late-Career Employees. Work Aging Retire. 2019, 5, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Rudolph, C.W. Why do we act as old as we feel? The role of occupational future time perspective and core self-evaluations in the relationship between subjective age and job crafting behaviour. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Terracciano, A. Feeling older and risk of hospitalization: Evidence from three longitudinal cohorts. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, B. Age identity: A cross-cultural global approach. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melehin, A.I.; Sergienko, E.A. Predictors of subjective age and emotional health in the elderly. Exp. Psychol. (Russia) 2015, 8, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergienko, E.A. Subjective and chronological human age. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya 2013, 6, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, N.; Le Fur, S.; Bougnères, P.; Valleron, A.J. Impact of social inequalities at birth on the longevity of children born 1914–1916: A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravesteijn, B.; van Kippersluis, H.; van Doorslaer, E. The contribution of occupation to health inequality. Res. Econ. Inequal. 2013, 21, 311–332. [Google Scholar]

- Solé-Auró, A.; Martín, U.; Domínguez Rodríguez, A. Educational Inequalities in Life and Healthy Life Expectancies among the 50-Plus in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C. Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1084–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Chen, S.; Yu, G.; Zou, Y.; Lu, H.; Wei, Y.; Tang, J.; Long, B.; Tang, X.; Yu, D.; et al. Comparations of major and trace elements in soil, water and residents’ hair between longevity and non-longevity areas in Bama, China. Int. J. Environ Health Res. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.; Pfeffer, J.; Zenios, S. Exposure to Harmful Workplace Practices Could Account for Inequality in Life Spans Across Different Demographic Groups. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2015, 34, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1997; Volume 14, p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, N.E.; Boyce, T.; Chesney, M.A.; Cohen, S.; Folkman, S.; Kahn, R.L.; Syme, S.L. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, D.M.; Lleras-Muney, A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, P.; Huysmans, M.A.; Holtermann, A.; Krause, N.; van Mechelen, W.; Straker, L.M.; van der Beek, A.J. Do highly physically active workers die early? A systematic review with meta-analysis of data from 193,696 participants. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimov, V.N.; Zharinov, G.M. Life span and longevity in representatives of creative professions. Adv. Gerontol. 2013, 26, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avgustova, L.I. To the Question of the Life Expectancy of Representatives of Psychological Science; Ananiev Readings-99; Publishing House of St. Petersburg University: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1999; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Berezkin, V.G.; Bulianitsa, A.L. On some demographic characteristics of the members of the Russian Academy of Sciences in the 20th century. Adv. Gerontol. 2007, 20, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reus-Pons, M.; Mulder, C.H.; Kibele, E.U.B.; Janssen, F. Differences in the health transition patterns of migrants and non-migrants aged 50 and older in southern and western Europe (2004–2015). BMC Med. 2018, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamia, C.; Trichopoulou, A.; Trichopoulos, D. Age at retirement and mortality in a general population sample: The Greek EPIC study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, H.; Muller, R.; Helmert, U. Time to retire—Time to die? A prospective cohort study of the effects of early retirement on long-term survival. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, N.E.; Carstensen, J.M.; Gjesdal, S.; Alexanderson, K.A. Mortality in relation to disability pension: Findings from a 12-year prospective population-based cohort study in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 35, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P.; Wendt, J.K.; Donnelly, R.P.; de Jong, G.; Ahmed, F.S. Age at retirement and long term survival of an industrial population: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2005, 331, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezina, T.N.; Buzanov, K.E.; Zinatullina, A.M.; Kalaeva, A.A.; Melnik, V.P. The expectation of retirement as a psychological stress that affects the biological age in the person of the Russian Federation. Religación Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 2019, 4, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, K.; Jarvinen, E.; Eskelinen, L.; Ilmarinen, J.; Klockars, M. Effect of retirement on health and work ability among municipal employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1991, 17, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berezina, T.N. Individual life expectancy as a psychogenetic feature. Voprosy Psikhologii 2017, 2017, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Berezina, T.N.; Mansurov, E.I. Influence of stress factors on life expectancy of cosmonauts. Voprosy Psikhologii 2015, 2015, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Berezina, T.N.; Ekimova, V.I.; Kokurin, A.V.; Orlova, E.A. Extreme image of behavior as factor of individual life expectancy. Psikhologicheskii Zhurnal 2018, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abulkhanova, K.A.; Berezina, T.N. Personality Time and Life Time; Aletheya: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Voitenko, V.P.; Tokar, A.V. The assessment of biological age and sex differences of human aging. Exp. Aging Res. 1983, 9, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voitenko, V.P. Biological age. In Physiological Mechanisms of Aging; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1982; pp. 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Markina, L.D. Determination of the Biological Age of a Person by V.P. Voitenko Method. State Medical University of Vladivostok. Available online: https://www.studmed.ru/view/markina-ld-opredelenie-biologicheskogo-vozrasta-cheloveka-metodom-vp-voytenko_d7e0de85f91.html (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Lorem, G.; Cook, S.; Leon, D.A.; Emaus, N.; Schirmer, H. Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: A cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganna, A.; Ingelsson, E. 5 year mortality predictors in 498,103 UK Biobank participants: A prospective population-based study. Lancet 2015, 386, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Romo-Pérez, V.; García-Soidán, J.L.; García-Liñeira, J. Percentiles and Reference Values for the Accelerometric Assessment of Static Balance in Women Aged 50–80 Years. Sensors 2020, 20, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Li, L.; Ye, X.; Wu, H.; Shen, B.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Niu, C.; et al. Evaluation of the reliability and validity for X16 balance testing scale for the elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A.; Kotter-Gruhn, D.; Smith, J. Self-perceptions of aging: Do subjective age and satisfaction with aging change during old age? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2008, 63, P377–P385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotter-Gruhn, D.; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A.; Gerstorf, D.; Smith, J. Self-perceptions of aging predict mortality and change with approaching death: 16-Year longitudinal results from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D.; DeSimone, A.J. Best practice recommendations for data screening. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, D.A.; Stillman, S. Return migration and the age profile of retirement among immigrants. IZA J. Migr. 2013, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nazroo, J.Y. Genetic, Cultural or Socio-economic Vulnerability? Explaining Ethnic Inequalities in Health. Sociol. Health Illn. 1998, 20, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Up to 35 | 36–50 | 51–65 | 66+ | |

| Russia | Women | 13 | 21 | 20 | 8 |

| EU sample | Women | 7 | 30 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | Men | 11 | 14 | 10 | 4 |

| EU sample | Men | 12 | 27 | 5 | 1 |

| Effectors | Place of Residence | Gender | Interaction of Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Relative biological ageing | 5.42 | 0.021 * | 77.78 | 0.000 * | 0.48 | 0.491 |

| Relative psychological ageing | 25.67 | 0.000 * | 3.21 | 0.075 | 0.21 | 0.648 |

| Subjective self-assessment of diseases | 11.71 | 0.001 * | 35.78 | 0.000 * | 0 | 0.969 |

| Static balancing | 0.83 | 0.364 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.908 |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Up to 35 | 36–50 | 51–65 | 66+ | |

| Russia | Women | −12.6 | −8.2 *,4 | −8.3 *,4 | −15.72,3 |

| EU sample | Women | −10.2 | −11.9 * | −12.8 * | −13.1 |

| Russia | Men | 0.8 | −1.93 | 3.94,** | −0.1 |

| EU sample | Men | 0.3 | −3.4 | −6.9 ** | −6.4 |

| Residence | SB (in Seconds) | SAH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| women | Russia | 35.9 | 9.2 * |

| EU sample | 31.2 | 7.1 * | |

| men | Russia | 39.8 | 5.4 * |

| EU sample | 36.2 | 3.2 * |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Up to 35 | 36–50 | 51–65 | 66 plus | |

| women | Russia | 18.3 **,2,3,4 | 0.91 | 0.3 **,1 | −1 |

| EU sample | −1.7 ** | −6.2 | −10.9 ** | −35.0 * | |

| men | Russia | 20.1 **,3,4 | 12.9 **,4 | 3.6 **,1 | −13.5 *,1,2 |

| EU sample | 6.3 **,2,3 | −5.7 **,1 | −20.4 **,1 | −12.0 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berezina, T.N.; Rybtsova, N.N.; Rybtsov, S.A. Comparative Dynamics of Individual Ageing among the Investigative Type of Professionals Living in Russia and Russian Migrants to the EU Countries. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 749-762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030055

Berezina TN, Rybtsova NN, Rybtsov SA. Comparative Dynamics of Individual Ageing among the Investigative Type of Professionals Living in Russia and Russian Migrants to the EU Countries. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2020; 10(3):749-762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerezina, Tatiana N., Natalia N. Rybtsova, and Stanislav A. Rybtsov. 2020. "Comparative Dynamics of Individual Ageing among the Investigative Type of Professionals Living in Russia and Russian Migrants to the EU Countries" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 10, no. 3: 749-762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030055

APA StyleBerezina, T. N., Rybtsova, N. N., & Rybtsov, S. A. (2020). Comparative Dynamics of Individual Ageing among the Investigative Type of Professionals Living in Russia and Russian Migrants to the EU Countries. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(3), 749-762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030055