Abstract

This study investigates the process of how the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) in automobile and consumer electronics industries design their supply networks. In contrast to the sociological viewpoint, which regards the emergence of networks as a social and psychological phenomenon occurring among non-predetermined individuals, this paper attempts to provide a strategic supply network perspective that views the supply network as a strategic choice made by an OEM. Anchored in the multiplex investigation of supply network architectures, this study looks into the following specific questions: (1) Are an OEM’s strategic intent choices associated with supply network architecture and (2) If so, what differential effects do those strategic intents have on the architectural properties of the supply network? Further field investigations were conducted to provide deeper insights into the quantitative and qualitative findings from statistical analyses.

1. Introduction

Faced with a changing business environment in which the coordination of the complex global networks involved in a firm’s activities is becoming a prime source of competitive advantage, more supply chain management (SCM) researchers have focused on the simultaneous interactions among multiple supply chain entities within the supply network, rather than searching for dyadic or triadic ties between one original equipment manufacturers (OEM) and its immediate supplier(s). Network thinking and analysis were originally regarded as a subtype within the general framework of structural sociology [1]. In certain respects, the field of sociology viewed the emergence of networks—the collection of interpersonal ties (e.g., kinship, friendship, communication, co-membership, etc.)—as a social and psychological phenomenon occurring among non-predetermined individuals through face-to-face conversations. In business settings, however, these networks do not spontaneously emerge from face-to-face interaction among non-predetermined individuals; rather, corporate managers strategically orchestrate these relationships by acting as network architects who designate the member companies of the network and its objectives [2]. In this vein, business academics have predominantly explored how a firm can manage its portfolio of multiple simultaneous alliances (e.g., [3,4,5]). Yet an important question still remains unclear: “What determines different network architectures” [6]; in other words, what are the strategic antecedents of network properties? Working from a strategic network perspective emphasizing the importance of network design in achieving a firm’s strategic objectives [7], Doreian [8] hints at the existence of antecedents of network architecture by asserting that the first principle of network formulation is that “networks have instrumental character for network members as these members have structured goals and some goals are achieved through network choices” (p. 95).

In the above vein, SCM researchers and practitioners have also conjectured the existence of antecedents for heterogeneous supply network architectures. For instance, facing a turbulent business environment, firms need to build and maintain multiple supply bases [9] which are “the portion(s) of the (bigger) supply network that is within the managerial purview of the focal company” (p.639) [10]. While it is obvious that the strategic network perspective should be considered an integral component of theory in SCM because researchers consider multiple entities commonly composed of large numbers of firms from multiple interrelated industries, empirical SCM research has confined itself to simple descriptions of supply network characteristics. Without considering the possible antecedents of network formulation, studies may give misleading answers about how different supply networks across various contexts should be managed. Goal conflicts are also more likely to arise in a supply network setting that essentially consists of multiple tiers of legally separate profit-making organizations with their own strategic goals; in other words, an OEM cannot attain supply chain success without deliberately designing its entire supply network in accordance with different strategic intents. Therefore, in exploring supply network phenomena, it is reductive to rely on the sociological viewpoint, which characterizes networks in terms of spontaneous and informal face-to-face conversations among non-predetermined individuals. Rather, a supply network should be viewed as a systematic outcome which is intentionally and strategically designed, implemented, and maintained in service with the OEM’s strategic intent(s).

In line with this argument, this study attempts to address a theoretical and empirical gap in supply network research by exploring the unknown strategic antecedents of different supply network architectures. Specifically, it looks into the following questions: (1) Are an OEM’s strategic intent choices associated with supply network architecture; and (2) If so, what differential effects do those strategic intents have, and which architectural properties of the supply network are effected? To categorize strategic intents, this study borrows from Fisher’s [11] supply chain design considerations where strategic intent is categorized by focus on cost leadership or market responsiveness. Drawing upon a unique dataset which allows analyses of multiple directed valued supply networks, this research sheds lights on the unresolved question of the supply network antecedents in a directed valued network setting and, consequently, offers a strategic supply network perspective. The remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical background and develops the hypotheses; Section 3 reviews the data, measures, and research methods used to test the proposed hypotheses; Section 4 provides the key results and interpretations; Section 5 presents the results of additional field investigations which provide further insights into the quantitative and qualitative findings, and is followed by Section 6 that discusses the contributions of this research and directions for future work.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Network Resource and Strategic Intent

Many sociologists traditionally viewed the emergence of social networks as the outcome of spontaneous and informal face-to-face conversations among non-predetermined individuals [12]. On the other hand, a stream of strategic alliance literature has adopted a different view in which firms utilize strategic alliances to access partners’ knowledge or skills [13] to hedge their performance risk [14], or to enter a certain foreign market [15] within interfirm dyad settings. This view has been anchored in the network resource theory (also known as social resource theory), one of the most popular theories in social network research. The theory, mainly developed by Lin et al. [16], argued that interpersonal contacts enable better access to, and mobilization of, resources embedded within and outside one’s social network, such as valuable information and prestigious connections [17,18]. However, relatively little is known about what specific motives drive interfirm network actors to interact with one another and attempt to form a specific network architecture.

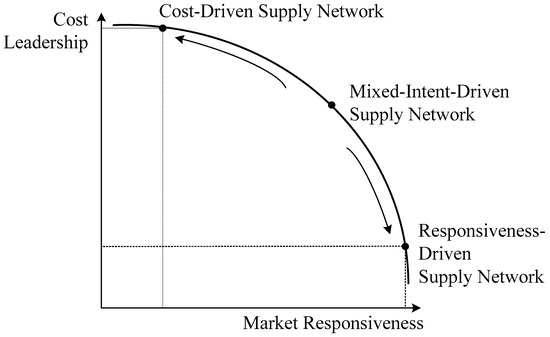

The concept of strategic intent initially suggested by Hamel and Prahalad [19] has been useful throughout various business disciplines in accounting for managerial motives behind the strategic alliance or joint venture formulation. While a vision is commonly developed and held by top management teams, strategic intent is more than just a vision or ambitious target of top management in that it is shared and implemented at multiple levels of the organization [20,21]. For instance, Koza and Lewin [22] proposed a framework emphasizing that a firm’s strategic partnership structure varied by its strategic intent (exploitation or exploration). DiRomualdo and Gurbaxani [23] also highlighted the importance of alignment between the strategic intent and supplier relationships to achieve outsourcing success. Ryall [24] more recently espoused this view in his argument that an OEM should utilize different strategic intents (competitive or persuasive) in garnering the resources and capabilities possessed by non-immediate members of its value network. Extending the aforementioned conceptual arguments to the SCM domain, the OEM’s strategic intents may serve as pivotal reference points for managing its supplying partners across multiple tiers, which result in different architectural properties of the formed supply network. Very little empirical research, however, has been done to test this conjecture. This study investigates the strategic antecedents of different supply network architectures by incorporating Fisher’s [11] supply chain design considerations (i.e., cost leadership and market responsiveness) as shown in Figure 1, and as a result, aims to provide a strategic supply network perspective.

Figure 1.

Strategic intents and corresponding supply network types.

2.2. Supply Network Tie Types

Ties across interfirm networks serve as conduits for network actors to access, transmit, or exchange critical organizational resources [25,26,27,28]. Interestingly, the same supply network can have multiple different architectural properties with regard to types and attributes of network ties (i.e., network resources), which is commonly referred to as “multiplexity” [29,30,31,32]. Thus, in accounting for interfirm network phenomena, such as supply networks, it is essential to take a network multiplexity approach in order to find “hidden” network architectures. This study considers four different supply network tie types—contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties—which interlink supply network partners. The first two types, contractual and transactional ties, represent visible network ties for the exchange of tangible network resources, such as goods and services, whereas the remaining two, professional and personal ties, capture the invisible (and mostly intangible) exchange of network resources between supply network partners.

Obviously, a supply network consists of visible ties, such as contracts or deliveries and receipt of goods and services [33,34]. Contractual ties are written agreements that seek to regulate interfirm transactions by specifying a detailed set of legally binding guidelines on operational requirements, quality monitoring and control, warranty policies, penalties, expected service level, etc. Another type of visible network ties considered is a transactional tie reflecting the amount of monetary exchanges, which have been regarded as a simple but clear manifestation of the economic transactions occurring within interfirm networks. Transactional ties represent the economic interdependence between network members. In other words, a buying firm becomes more dependent on the supplier as the percentage of its total payments to a specific supplier relative to other suppliers increases while the same occurs to the supplier when a greater percentage of its total sales comes from a specific buying firm relative to others. Although the most fundamental element of economic exchanges between supply chain partners, a contractual tie (i.e., a formal written contract between one supply network actor’s sourcing partner) by its very nature can both foster and hinder commitment between buyers and sellers [35,36]. For instance, a stronger contractual tie (i.e., more complete contract) including explicit work-related provisions and prescriptions, can protect buyers from the opportunistic behavior of their counterparts [37]. Viewed from a supplier’s standpoint, on the other hand, a strong contractual tie specifying more control and legal rules can serve as a threat when buyers opportunistically utilize it to impose unreasonable terms and conditions on the supplier [38,39]. In this vein, a transactional tie (i.e., the actual exchange of goods and services) can be established without a formal written contract when both parties share relational norms such as reciprocity, solidarity, and information sharing [40,41,42]. This study thus regards the above two visible supply network ties (i.e., contractual and transactional ties) as separate types in which a stronger contractual tie does not necessarily imply more or less economic transactions and vice versa.

Prior network research has pointed out that much of an interorganizational commitment is often formalized at a personal, rather than organizational level, and hence, the arrangement can offer exclusive access to network resources [43,44,45]. However, interpersonal and thus invisible ties in supply networks have received relatively less research attention, whereas visible network ties representing economic exchange have been actively discussed in the literature. Thus, this study also considers two invisible network ties (i.e., professional and personal ties) that bridge the supply chain personnel of partnering firms. Professional ties are normally task-oriented and focus on achieving assigned objectives, while personal ties deal more with the social/emotional side of non-work-related interactions and focus on interpersonal likeability [46,47]. In an SCM context, these invisible ties between purchasing and supply managers play a crucial role in facilitating buyer-supplier cooperation, trust, reputation and image, and subsequent organizational performance [48,49,50,51]. When incorporated with social network analysis, this consideration further enables the inter- and intra-comparisons of different tie types and comparable network indices and consequently can provide invaluable insights concerning the underlying network architecture [52,53]. Table 1 provides conceptual definitions of the four supply network tie types under consideration and their measurement items used based on the literature.

Table 1.

Conceptual definitions, item measures, and related literature for supply network tie types.

2.3. Indices for Network Characterization

To demonstrate different supply network architectures consisting of the four aforementioned heterogeneous supply network ties (i.e., contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties), this study adopts social network analysis (SNA), which has long been used in analyzing any social network as a set of interrelated actors and ties. The field of SCM has stressed the potential applicability of SNA in a supply network context. For instance, Carter et al. [54] proposed SNA as a valuable complement to traditional methodologies which may be used to advance current knowledge on various relationships existing within and beyond the supply chain. This view was echoed by Borgatti and Li [53] who pointed out that supply chain settings are particularly suitable for SNA indices, which have proven “highly portable” across other disciplines from economics to physics. More recently, Galaskiewicz [55] also noted that SCM theories mostly captured at the local level (e.g., dyad or triad) can be tested by using a supply network as the primary unit of analysis.

Despite repeated calls for such approach, there are still very few SCM studies that use SNA, (e.g., [34,56,57]). Moreover, the vast majority of existing studies on supply network are case-based research that uses SNA measures defined for binary (i.e., “1” if a tie exists between two supply network entities, “0” otherwise) and non-directional ties (i.e., if one supply network entity perceives a tie, its counterpart’s perception of the existence of the tie is automatically assumed). This is commonly referred to as the binary network approach, and most of the existing SNA indices have been devised solely based on this approach [58,59]. The binary network approach specified by a symmetric adjacency matrix is conceptually and computationally straightforward and especially appropriate when a researcher focuses on cognitive ties (e.g., who knows whom). An important limitation of this approach, however, is that it involves an unrealistic premise—all ties are completely homogeneous and symmetrical—which contradicts previous findings in the literature. For instance, strong social ties strengthen interpersonal obligations [17], facilitate change in the face of uncertainty [60], and help to develop relationship-specific heuristics [61]. Therefore, by using the binary network approach, network researchers can inevitably overlook important information about network properties embedded in network ties and consequently arrive at limited or even misleading implications for network architecture.

We thus adopted a directed valued network approach represented by an asymmetric adjacency matrix to overcome the aforementioned shortcomings of the binary network approach [58,59]. This approach takes into account the direction and strength (or magnitude) of each tie between different network entities. In network terms, a directed valued network consists of a set of actors (or nodes) , a set of arcs (i.e., directional ties or links) , and a set of values attached to the arcs, subject to where is not necessarily equal to . This is a more useful and realistic approach for exploring supply network phenomena since it allows for the possibility that a focal firm and its suppliers may view the strength (or even the existence) of their ties differently. In this sense, there has been a growing need for SNA indices that can be used in the directed valued network setting when it is based on a different adjacency matrix.

More specifically, this study focuses on four socio-centric network indices (i.e., betweenness centralization, in-degree centralization, out-degree centralization, and global clustering coefficient), which describe the overall pattern of multiple actors within a single, bounded network. While ego-centric indices, such as centralities, deal with a particular actor’s (i.e., ego’s) position within the network, they provide a better understanding of the directed valued network in that the network architecture from one ego’s viewpoint can be markedly different from those of others linked directly or indirectly [62,63]. They also fit perfectly with the purpose of this study to explore the association between an OEM’s strategic orientation and the supply network architectures it creates based on different types of supply network ties. Table 2 proposes a new framework for the supply network implications of the socio-centric SNA indices for the directed valued networks used in this study for four types of supply network ties.

Table 2.

Socio-centric indices, conceptual definitions, and interpretations by supply network tie.

First, betweenness centralization (BTC) represents whether most network actors are equally central, or some actors (i.e., hubs) are much more central than others. This index can be calculated by dividing the variation in the betweenness centrality by the maximum variation in betweenness centrality scores possible in a network of the same size [64]. Betweenness centrality is an ego-centric index indicating how often an actor lies on the shortest path between all combinations of pairs of other actors. The higher an actor’s betweenness centrality, the more its immediate counterparts depend on this actor to reach out to the rest of the network. This index focuses on the role of an actor as an intermediary and posits that the dependence of others makes the actor central in the network. BTC, a socio-centric version of betweenness centrality, ranges from 0 where all network actors have the same betweenness centrality, to 1, where there exists one single actor connecting all the other actors. This study calculates the BTC of a directed valued supply network by adopting the formula suggested by Opsahl et al. [65] for betweenness centrality () for network actor , defined as:

where is the total number of geodesics between two actors ( and ), is the number of geodesics passing through actor , and is a positive tuning parameter that is set to the benchmark value of 0.5 to equally value both the number of ties and their strengths (). Thus, BTC can be formally expressed as:

where is the largest value of the betweenness centrality that occurs across the network ; that is,.

In the case of a directed network, two additional degree indices are defined: in-degree, or the number of links terminating at the actor (), and out-degree, or the number of ties originating from the actor () [58]. In-degree centralization (IDC) calculates the dispersion of or variation in in-degree centrality, and the extent of an individual actor’s influence on other actors; thus, high IDC indicates the incoming flows of different network resources are focused on a small group of actors in the overall network. In the same sense, high out-degree centralization (ODC) indicates that a small number of actors send out most of the network resources to the rest of the network actors. This study derives IDC and ODC of a supply network from in-degree centrality () and out-degree centrality () for actor of a directed valued network using the following equations [65]:

where and are the total strengths attached to the incoming and outgoing ties, respectively. Therefore, the general IDC and ODC ranging from 0 to 1 are respectively defined as:

where and are the largest in-degree and out-degree centrality values in the network .

Lastly, this study uses a global clustering coefficient (GCC) varying from 0 to 1 to measure the overall level of cohesion among network actors [66,67]. In social network terms, this indicates the probability that network actors and are also connected to each other when is connected to both of them, collectively represented as . In a directed valued network setting, this socio-centric index is defined as the total value of closed triplets (i.e., triples of network actors where each actor is connected to the other two; ) divided by the total value of triplets (i.e., triples where at least one actor is connected to the other two; ). Triplet value () calculation is based on the geometric mean of the tie values for the nodes comprising the triplet in that it: (1) Captures differences between tie strengths, and (2) is robust to extreme tie strength [68]. Thus, the general GCC () can be formally stated as:

where is the number of possible triplets in network G. Readers can refer to the recent study of Opsahl and Panzarasa [68] for more details on this technique.

Because SNA indices have been developed and used within a sociological context, they cannot be directly applied and interpreted within an interfirm supply network context. Table 2, consequently, proposes a new framework for the supply network implications of the socio-centric SNA indices for directed valued networks used in this study for each of the four tie types previously defined in Table 1.

2.4. Hypotheses

A firm has a power advantage when it is relatively less dependent upon the resources of its counterpart(s), and it often leverages this power over others to achieve intended strategic goals [35,69]. Social network studies have adopted betweenness centrality to measure an individual actor’s power, and the extent to which it controls the resource flows in its network. As a socio-centric measure indicating the variation of the betweenness centralities of all network actors, BTC characterizes the extent to which the overall network is built around a particular group of actors serving as hubs relative to the rest of the network [62,64]. A low BTC score indicates that the network resources running through various types of ties are almost equally distributed across the entire network, whereas a high score indicates that there exist particular focal firms possessing more network resources. This measure can be interpreted differently for different supply network tie types. For instance, an OEM pursuing a cost leadership strategy will try to make supply contracts as complete and detailed as possible to reduce any uncertainty, which may translate into cost savings [70,71] and, as a result, the OEM will pursue unequal contracts with its supply network members. On the other hand, the lack of predictability of market changes prevents OEMs from designing complete supply contracts when they pursue market responsiveness, and this will result in cooperative, but loose, contracts containing rather general information [72,73]. Regarding transactional ties, an OEM pursuing a cost leadership strategy can exploit economies of scale by focusing on a relatively small number of supply network members, whereas if that OEM is interested in responding promptly within an unsteady market, it would diversify its supply sources. This distinction is also observed for the supply networks consisting of professional and personal ties. In other words, a supply network actor devoted to cost leadership may tend to interact with a smaller range of counterparts, while it establishes a broader array of professional and personal interactions with other supply network members to be more responsive to market-led changes. Personal and professional ties in a market-responsiveness focused supply network, especially, might be expected to lead to more frequent interactions involving a greater number of actors to allow them more options in responding to an unstable environment. In this environment, information-seeking and problem-solving behaviors can be expected to dominate, resulting in more interactions with a greater number of network partners. Based on this line of reasoning, the following set of hypotheses is proposed:

Hypothesis 1A.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing cost leadership is positively associated with the BTCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties.

Hypothesis 1B.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing market responsiveness is negatively associated with the BTCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties.

A firm with more power over their counterparts also can more easily draw and absorb network resources from the rest of its network by exerting coercive or punitive pressure and, consequently, can achieve its strategic goals [74,75]. In social network research, this power of an individual network actor is commonly measured by in-degree centrality, which represents the total number of ties pointing toward the actor. IDC, derived by the variation in individual actor’s in-degree centrality at the network level, indicates the extent to which network resources are concentrated in particular actors [58]. From a supply network perspective, an OEM trying to achieve cost leadership by pursuing economies of scale will have a network architecture with a relatively small group of members, which brings in more transactional, professional, and personal inflows from the rest of the network. A firm seeking market responsiveness, in contrast, will try to hedge against unexpected market changes using a diversification strategy and, as a result, will have a supply network architecture demonstrating relatively equal distributions of transactional, professional, and personal inflows across network members. The supply network in-degree centrality accounting for contractual ties may need more cautious interpretation because complete contract terms can impose institutional constraints on interorganizational transactions [76,77,78,79]. More inflows of complete contracts (i.e., high in-degree centrality) thus indicate that a network actor receives the less favorable (or more restrictive) terms and conditions from its counterpart(s). In this sense, OEMs which need tight cost controls may build supply networks where a few focal firms take up more favorable (i.e., less complete) contracts showing low IDC, whereas their strategic intent of achieving market responsiveness drives the opposite consequence (i.e., supply network members have mutually favorable—that is, equally complete—contracts with others). The preceding discussion leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2A.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing cost leadership is positively associated with the IDCs of its supply networks consisting of transactional, professional, and personal ties, while being negatively associated with the supply networks consisting of contractual ties.

Hypothesis 2B.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing market responsiveness is negatively associated with the IDCs of its supply networks consisting of transactional, professional and personal ties, while being positively associated with the supply networks consisting of contractual ties.

In addition, a firm may relax its own institutional constraints on other exchange partners expecting reciprocal behavior, and in doing so may make advances toward cost leadership or market responsiveness [61,80]. This is true especially when both parties have complementary resources or similar sources of uncertainty and can provide more useful feedback to refine their efforts for their own benefit [81,82]. Companies such as Dell and Whirlpool, for example, transformed themselves into “virtually integrated” organizations by sharing their information and knowledge on inventory level and sales forecasting with other supply network members. A network actor’s use of this kind of influence on its exchange partners has been measured by out-degree centrality that denotes the number of network ties originating from the actor. As a socio-centric measure indicating the variation of the out-degree centralities of all network actors, ODC explains the extent to which particular actors distribute transactional or relational network resources to others [58]. In other words, a high ODC score indicates that a few particular focal firms disseminate most of the transactional or relational network resources for the rest of the members, whereas a low score indicates that each member of the network has a more equal amount of those resources. This measure would be interpreted differently for each type of supply network tie. For instance, when OEMs seek cost leadership, their supply networks will have an architecture consisting of a small group of firms that send out more complete (i.e., less favorable) contract terms and a greater number of monetary exchanges for the rest of the network. They will not be very interested in establishing reciprocal professional and personal ties since those relationship-specific investments can increase switching cost as well as prevent their search for lower cost suppliers [83]. On the other hand, OEMs pursuing market responsiveness will be more willing to initiate more professional and personal interactions with other network partners to detect potential market changes while maintaining a balanced approach toward contract completeness and quantity. This reasoning leads to the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3A.

An OEM’s strategic intent to pursue cost leadership is positively associated with the ODCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual and transactional ties, while being negatively associated with the supply networks consisting of professional and personal ties.

Hypothesis 3B.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing market responsiveness is negatively associated with the ODCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual and transactional ties, while being positively associated with the supply networks consisting of professional and personal ties.

Direct contacts and connections between a firm and its customers/suppliers also facilitate the exchange and distribution of organizational resources and subsequently contribute to the strategic goals and competitive advantage of the involved actors [84,85]. For instance, Japanese automobile manufacturers such as Toyota and Nissan have endeavored to maintain direct connections with non-immediate suppliers by means of different supplier associations and considerable owner interest in their suppliers [86,87]. Those efforts enabled them to oversee the whole supply network by supplementing the potential shortcomings of a hierarchical supply network, characterized by a reliance on a limited number of first-tier suppliers. In social network research, such connectivity among network actors has been measured by GCC that denotes how cliquish (or tightly knit) a network is as a whole [66,67]. In plain terms, it measures the probability that the friend of John’s friend is also John’s friend. In a supply network with a low GCC, network actors interact with only a few contiguous others which results in a hierarchical (i.e., more cliquish) architecture as a whole. A high coefficient value, in contrast, suggests more actors are directly connected to one another manifesting lateral (i.e., less cliquish) network architecture. From a supply network perspective, an OEM’s intent to acquire cost leadership will drive it to build a hierarchical supply network which allows for easier and more thorough control on a limited number of major suppliers. A firm interested in achieving market responsiveness, on the other hand, will try to establish direct connections with as many down-tier suppliers as possible in order to perceive and respond to changing market circumstances, which subsequently leads to lateral supply network architecture. Accordingly, this study investigates the following set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4A.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing cost leadership is negatively associated with the GCCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties.

Hypothesis 4B.

An OEM’s strategic intent of pursuing market responsiveness is positively associated with the GCCs of its supply networks consisting of contractual, transactional, professional, and personal ties.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

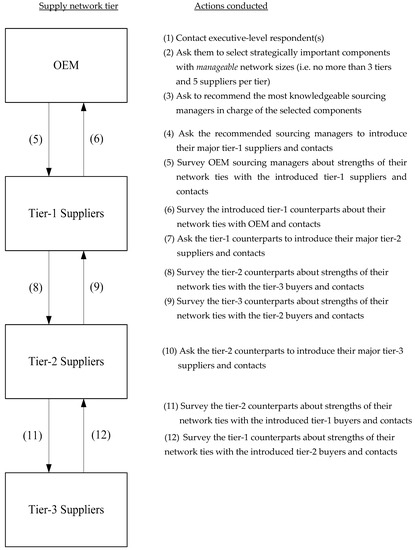

Given the interests of this study, a quantitative method of a survey-based questionnaire was employed to collect the data about an OEM’s component-level strategic intent, and the direction and strength of ties among all supply network partners involved in supplying the selected component. Most often, a single product is built up by incorporating a mix of functional and innovative components [88,89], and on this account a few notable studies such as Huang et al. [90] and Kim et al. [34] have used the component- (or module-) level supply network approach. In collecting network data, the boundaries of each component-level supply network should be specified first in order to avoid potential distortions in describing the overall network architecture [91,92,93]. Initial OEM (i.e., tier-0) contacts mostly at the executive level were thus asked to select a strategically important component with a manageable network size (i.e., no more than 3 tiers and 5 suppliers per tier) and recommend the most knowledgeable sourcing manager in charge of the selected component. This step also helped to minimize key informant bias [94]. Next, a combined sampling approach of fixed list and snowball selections was adopted based on the selected components [53,95,96]. The recommended sourcing managers were asked to evaluate their perceptions of different types of ties (i.e., contractual, transactional, professional, and personal) with their major immediate suppliers, most of which were listed as the OEM’s preferred supplier. The same questions were given to the OEM’s counterparts (i.e., tier one suppliers) based on the contact information provided by the OEM’s sourcing manager, and this dyadic data collection process was repeated for the successive tiers of suppliers (i.e., tier two and tier three suppliers) until end-tier suppliers were reached. To check for the existence of duplicate network partners, surveys on lower-tier suppliers were conducted after finalizing all the surveys on their immediate upper-tier buyers. The overall data collection process is illustrated in the flow chart in Figure 2. As a result of these efforts, a total of 153 component-level networks of three major South Korean automobile and consumer electronics manufacturers consisting of 1852 total network members were collected. Table 3 presents the demographics and descriptive statistics of the study population.

Figure 2.

Data collection process.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and ANOVA results.

3.2. Measures

Capturing Strategic Intent

The measures for the component-level strategic intent were adopted from extant studies such as Gunasekaran et al. [97] and Li et al. [98]. OEM-level respondents, not knowing which item corresponded to which strategic intent, were asked to answer “yes” or “no” for each of the eight measure items shown in Table 4. A score of +1 was given to “yes” responses to the first four items representing cost leadership, while those of the latter four items for market responsiveness received −1. “No” responses were given a value of “0” for both intents. These response scores were summed up, creating a 9-point scale ranging from −4 to +4, and used to pre-classify the collected 153 component-level supply networks into three groups based on strategic intent: Cost leadership (from +2 to +4; N = 42), market responsiveness (from −4 to −2; N = 36), and mixed (from −1 to +1; N = 75).

Table 4.

Bivariate correlation matrix.

Validation of this pre-classified group membership was implemented by incorporating K-means clustering and SPSS’s Crosstabs procedure. This approach was previously used by Frohlich and Westbrook [99] to validate their classification of “arcs of integration.” As a widely applied method of ordinary cluster analysis, the K-means clustering identifies relatively homogeneous groups of cases for selected variables [100]. It seeks elements that have distances from the mean of their own group that are larger than those from another group. The element is then shifted to this group. This process stops if all elements have found ‘their’ groups. Group memberships for each of the three strategic intent groups were saved and then compared using the Crosstabs procedure. Crosstabs was used to count the number of cases that were in common between the two classifications and to calculate bivariate statistics. Table 5 shows the results of this validation approach. The Pearson’s correlation between group membership for the two classification procedures was 0.4620 (p < 0.000). Taken together, these measures confirm the validity of the employed classification method for component-level strategic intents.

Table 5.

Statistical pairwise comparisons between socio-centric indices.

3.3. Methods

Multinomial logit (MNL) analysis was carried out to understand the association between strategic intent groups and supply network tie types for each network index (i.e., Hypotheses 1–4), while controlling for the component type dummy (0 for electronic; 1 for mechanical) of each supply network. Table 6 presents descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for variable.

If X is the vector of network indices explaining the marginal effects of three strategic intents (i.e., cost leadership, market responsiveness, and mixed), the general form of the MNL model are expressed as:

where , , and correspond to each strategic intent. For model identification, in this case, the “mixed” strategic intent was chosen as a reference group (by putting ) in that Fisher’s [11] framework presented only two strategic considerations—cost leadership and market responsiveness—in designing supply chains. This was also appropriate as the sampling frame of this study consisted of respondents in either the electronics or automotive industries. The electronics industry is characterized by rapid changes in technology and shorter lifecycles where competition revolves around better market responsiveness. As a more mature industry, the automotive industry is characterized by relatively slow technological evolution, longer product lifecycles, and hard price competition. In these regards, the usage of the “mixed” strategic intent group as a reference in the current MNL is a reasonable approach which enables finding a clearer distinction between these two conflicting strategic intents. The above equations therefore can be rephrased as:

As a result, the first two equations above only calculated the relative probability of a strategic intent (either cost leadership—coded as Group 1—or market responsiveness—coded as Group 2) compared to the mixed intent (coded as Group 3), not the absolute probability. In other words, the relative probabilities of Groups 1 and 2 to the mixed intent are:

These ratios are referred to as the relative risk, and the ratio for one-unit change in a network index () then becomes or . The exponential value of the estimated coefficient is the relative risk for a one-unit change in the corresponding variable. In this sense, a relative risk less (or greater) than one indicates a negative (or positive) association between network index and strategic intent. Therefore, all the other estimated parameters can also be interpreted as a marginal effect (i.e., change in the odds ratio) of a network index associated with the strategic intent as opposed to mixed intent. The parameter vectors () were estimated using the maximum likelihood method.

4. Results and Interpretations

A series of MNL models were estimated to test the hypotheses. As noted above, analyses focused on the likelihood that supply networks have either cost leadership (Group 1) or market responsiveness (Group 2) intent rather than the mixed (Group 3) intent. Table 7 summarizes the empirical results on the associations between supply network characteristics and strategic intent. The likelihood ratio (LR) chi-square test statistics with 10 degrees of freedom indicated that all models are significant at the 1% level (94.89 for Model 1; 99.17 for Model 2; 83.19 for Model 3; 103.33 for Model 4). This provided preliminary support for the presented hypotheses by showing that the hypothesized network characteristics accounted for significant variability in strategic intent. In terms of the control variable, it was found that mechanical components were significantly associated with cost leadership intent, which was generally consistent with previous findings on the impact of product types on the choice of supply chain strategy (e.g., [11,101,102,103]). For the sake of brevity, the estimated coefficients and their significance levels will be used mainly for model interpretations, while other estimates (e.g., standard errors, relative risk, etc.) are also included in Table 7 for completeness.

Table 7.

Results of multinomial logit estimation.

Besides the theoretical and statistical considerations, field investigations were also deemed necessary to interpret supply network phenomena from a more realistic perspective, and consequently, to further support the contention that an OEM’s specific strategic intents play a central role in designing supply networks with differential characteristics. For verifications of the empirical findings and preliminary interpretations of the models, we revisited the members of several component-level supply networks and conducted follow-up interviews to determine: (1) What supply network management practices are being implemented, (2) how long they have been using those practices, and (3) why and how those practices worked (or did not work, if applicable) to achieve specific strategic intents and lead to the revealed network properties. This would provide a more comprehensive and real-world perspective on the association between the strategic intent and the corresponding network architecture. The exact names of companies, products, components, and technologies are replaced with letters for anonymity.

4.1. Model 1: Strategic Intent and BTC

Model 1 testing the associations between strategic intents (either cost leadership or market responsiveness) and the BTCs of different tie types provided four significant results altogether. Specifically, compared to OEMs focusing on mixed intent, the ones pursuing cost leadership were more likely to have supply networks characterized by: (1) Unequal completeness of contract terms among network members (B = 76.710, p < 0.01), and (2) concentrated transactions (i.e., large proportions with few network members) (B = 21.530, p < 0.10). Based on the follow-up interviews, it was confirmed that those observations were based on the logic of cost savings via complete contracts and economies of scale as expected in hypothesis H1A. For instance, one sourcing manager at a large automobile OEM noted: “It can vary case by case, but the baseline strategy for cost and quality control is continuing bulk purchases from a few select vendors who can accommodate every single detail of our proposed terms and conditions.”

Interestingly, contrary to the hypothesis, survey results showed that supply network personnel of Group 1 were more inclined to have a broader array of personal interactions in relatively equal portions (B = −20.594, p < 0.05), while the personnel pursuing market responsiveness interact with a smaller range of personal interactions in an unequal manner (B = 17.498, p < 0.05). These observations can be interpreted as evidence that supply network personnel may be utilizing their personal contacts for purposes of control, that is, to monitor whether their counterparts offer the best (i.e., lowest) possible cost. One interviewee, the founder and CEO of a tier-1 supplier for an automobile OEM confirmed this conjecture by stating:

“Information about cost structure is extremely sensitive for all down-tier suppliers since the buying firm can easily calculate our profit margins, which is not good for us. They (the buying firm) already keep asking us to cut down price while maintaining the same quality level as their products are under fierce price competition. Unfortunately, but inevitably, we are expecting and asking the same thing from and to our suppliers (tier-2).”

One senior-level purchasing manager at an OEM commented on this situation:

“We already know and understand that they (down-tier suppliers) do not like to share all the information about cost structure. I guess the cost information shared upon our request is 1 to 2 years old or rough numbers only. We cannot simply switch to other alternatives because it raises issues of uncertainty in terms of quality, communication, searching cost, etc. Based on my experience, a quick check for whether their profit margins are reasonable is to meet multiple low-level employees and ask them how their boss is doing during casual conversation. If he recently bought a new car or traveled abroad, for instance, it tends to signify that there is room for additional cuts.”

In the market responsiveness versus mixed setting, the only significant result showed that the aforementioned monitoring practice via personal interactions stood in contrast for OEMs focusing on market responsiveness. In other words, an OEM pursuing higher market responsiveness concentrates on a few trustworthy network members with strong personal ties and restricts others. One of our Group 2 respondents at a large consumer electronics OEM provided the following hint concerning this observation:

“I admit that utilizing personal relationships is a key in coping with technological and environmental market uncertainties. At the same time, however, it does not seem reasonable to put too much weight on building and maintaining personal relationships with all the existing down-tier suppliers. Although our market environment changes rapidly, a meteoric rise rarely happens in this business. For instance, the current key technology “A” for component “B” was introduced by one of our few but long-time (more than 8 to 10 years) tier-1 suppliers who have accumulated enough experience and resources to search for the next big thing. We have maintained a short list of the strongest candidates instead of completely predicting what changes will occur. This rule has been worked well so far.”

4.2. Model 2: Strategic Intent and IDC

Model 2 yielded four significant associations in hypothesized directions, which collectively supported the associations between strategic intent choices and ODCs. The first two results in cost leadership (Group 1) versus mixed intent (Group 3) comparison demonstrated that the supply network IDCs based on its transactional (B = 37.792, p < 0.10) and personal ties (B = 41.345, p < 0.05) were higher than the IDC values focusing on mixed intent if an OEM pursues cost leadership. In other words, compared to Group 3, an OEM’s intent to tackle costs seems to be associated with supply networks characterized by fewer particular focal firms that have higher incoming transaction percentages and more non-work-related interactions than the other network members. Follow-up interviews provided more information on the managerial decisions that led to these outcomes. On the positive coefficient of transactional IDC under cost leadership, one executive-level respondent of an automobile OEM confirmed the hypothesized logic by stating:

“Yes, we try to achieve economies of scale in purchasing to reduce costs. We further encourage our immediate (tier-1) suppliers to keep searching for down-tier suppliers who can provide lower cost for them because that also matters to us. As a result, there must be a relatively small number of firms which draw in more transactions than others. Why don’t we simply replace them with Chinese suppliers who can possibly offer lower deals? Considering issues such as quality, security, communication, wage, etc., they can increase total costs while reducing manufacturing costs.”

Interestingly, the tier-1 counterpart of the above OEM was seeing this transaction in a very different way. This contrast provides hints to explain how an OEM can pursue a cost leadership strategy by having a particular group of supply network members paying close attention to the non-work-related interactions among other network members. He replied as follows:

“Well, I cannot agree with his argument at all. Who will provide the expected price under cost competition with other OEMs? It is the OEM. As they make a bulk purchase for economies of scale, small and medium-sized suppliers like us are heavily relying on them. By utilizing this bargaining power, they continuously press us to drop our markups by implying that they can always switch to Chinese alternatives. We also keep searching for cheaper sub-suppliers around the world, but below a certain price, often we must compromise or sacrifice the current quality level which will eventually backfire on us. As a result, we pay special attention to establishing a personal relationship to gain their trust. For example, we regularly hire the OEM’s retiring executives or managers to build and maintain close personal relationships with the OEM.”

The next two results in the setting of market responsiveness (Group 2) versus Group 3 also showed predicted patterns for the IDCs of supply networks based on their transactional (B = −36.833, p < 0.10) and personal (B = −41.923, p < 0.01) ties. This means that, when an OEM pursues market responsiveness, its supply network is more likely to have network architectures in which each member has relatively equal amounts of incoming transactional and non-work-related flows from others compared to Group 3. This suggests an OEM can better react to market changes by getting more network members involved in exchanges of monetary transactions and non-work-related interactions. One purchasing manager at a consumer electronics OEM explained the transactional inflows by stating that: “We build a diversified sourcing portfolio for our component “C” with a short life cycle and uncertain demand. Not surprisingly, most of our immediate (tier-1) suppliers are not dedicated to us either to realize the maximum benefits from the current generation of the component, and they even supply to other OEMs including our competitors. Their sub-suppliers (tier-3s) think and act alike.” Regarding the relatively equal inflows of non-work-related (i.e., personal) ties, one tier-1 counterpart personnel of the above OEM noted:

“I admit that we have a pretty high level of autonomy, but they (OEMs) still have a position advantage in sensing and responding to market uncertainties such as consumer demand, price, and end-consumers’ tastes. Unfortunately, OEMs are reluctant to share that information with us because we are doing business with other OEMs including their suppliers, and thus the opportunities of information sharing through professional seminars, workshops, or training are lacking. We try to obtain such information via personal communication. Seeing your result that every network member has almost equal amount of incoming personal ties, it seems our downstream (tier-2 or tier-3) suppliers must be doing the same to our sourcing managers. Well, it is interesting to see everyone got on the same bandwagon.”

4.3. Model 3: Strategic Intent and ODC

Model 3 tested the associations between strategic intents and ODCs of four supply network tie types. The results showed partial support for both hypotheses H3A and H3B. First, in a Group 1 versus Group 3 comparison, it was shown that OEM’s cost leadership intent seemed to be positively associated with the ODC of its supply network composed of professional ties (B = 73.708, p < 0.01), whereas it showed a negative association for the same index of personal ties (B = −27.289, p < 0.05). The result statistically indicates, compared to Group 3, that the OEMs pursuing cost leadership tend to have a supply network architecture characterized by a few particular focal firms that send out most of the work-related interactions to the rest of the supply network members, and every supply network member has a relatively equal amount of non-work-related interactions with others. This implies that an OEM can achieve cost leadership by actively reaching out to other network members and introducing cost-saving practices to them, while extensively communicating with most other network members in a non-work-related context. On these phenomena, the purchasing manager at a consumer electronics OEM commented as follows:

“We emphasize the importance of persistent searching for possible supplier alternatives to achieve our price goal. Regular and frequent interactions such as business meetings, conference calls and other formats of online communication have been useful to ensure our suppliers (tier-1) invest enough efforts to progress.” He also added, “Meanwhile, overly close personal relationships with suppliers can put us in awkward situation when we have to lay off the ones that fall short of our expectations. We thus always try to keep personal distance.”

On the contrary, in the setting of Group 2 versus Group 3 comparisons, the ODCs of personal ties showed a positive association with market responsiveness intent (B = 27.576, p < 0.05). This observation shows that a small group of supply network members initiates more non-work-related interactions with others when the OEM focuses on market responsiveness, as conjectured in H3B. One executive-level respondent at a tier-2 automobile component supplier explained this finding as follows:

“Our customers (tier-1 suppliers) are closely working with their buyers (OEMs). Considering the technology level of sub-components, unfortunately, they have a relatively wider range of options for finding sub-suppliers like us—they can simply switch to one of our competitors. In order to avoid or at least delay this situation, we try to build and strengthen a close personal relationship with them, and sometimes hire their retiring executives with no manufacturing background for this. This also has been very effective in preventing the retirees with plenty of ‘friends’ in this business from starting their own company, which can be a threat to us.”

4.4. Model 4: Strategic Intent and GCC

The Model 4 demonstrated partial support for hypotheses H4A and H4B examining the associations between strategic intent choices and GCCs. Contrary to the predicted outcome, when an OEM pursues cost leadership, its supply network seems to be positively related to the GCCs of contractual (B = 45.204, p < 0.01) and personal (B = 41.407, p < 0.01) ties. In contrast, the OEM’s supply network showed a negative association with the GCC based on professional ties under the same intent (B = −99.201, p < 0.01). These results collectively indicate that, compared to mixed intent, OEMs focusing on cost leadership for their components tend to have supply networks in which: (1) More network members are connected to one another with complete contract terms and non-work-related interactions, and (2) less of them are connected with work-related interactions. These findings collectively suggest that an OEM can achieve cost leadership by designing a hierarchical structure regarding work-related responsibilities while maintaining a lateral structure for non-work-related communication. A follow-up interview with a purchasing manager of an automobile OEM provided the rationale to interpret the positive association between cost leadership and GCC of contractual ties. The respondent noted:

“When we source a cost leadership-focused component, the rule of business is quite simple: the supplier who can offer a lower price with reasonable quality wins the deal. The cost part is easy, but it is hard to be sure whether the supplier can meet our expectations on quality. Thus, when discussing and developing contract terms with tier-1 suppliers, we mostly ask them to provide a list of current or potential lower-tier suppliers and to include terms and conditions outlining the quality requirements for sub-components.”

Regarding the next two findings (i.e., the positive and negative estimated coefficients for personal and professional interactions), he stated:

“These two are unexpected, but wholly make sense. Although we try to check sub-suppliers’ quality conformance, it is still officially the tier-1 supplier’s right and responsibility, and hence we cannot directly communicate with lower-tier suppliers on work matters which might lead to the hierarchical network structure of professional interactions. However, we still can indirectly do our part via extensive personal communications, while not directly asking about work-related issues. There are hundreds of possible ways to do this. We also can inquire into the reputation of our original contractor’s sub-supplier through another tier-1 supplier’s sub-supplier, while not violating the original contract.”

Lastly, it was shown that an OEM’s market responsiveness intent seemed to be negatively associated with the GCC of its supply network composed of personal ties (B = −39.741, p < 0.01) as opposed to the hypothesized direction. This observation indicates that, compared to mixed intent, supply network personnel pursuing market responsiveness are more inclined to have a disconnected network of non-work-related interactions. The founder and CEO of a tier-1 supplier for a consumer electronics OEM explained this phenomenon as follows:

“Several governmental, quasi-governmental, or private organizations hold exhibitions and conferences to help the business entities in dealing with this fast changing market. We regularly participate in those events to socialize. Although participants do not explicitly share sensitive work-related information, those events have been regarded as “must go” events not to be isolated from other supply network members. Good personal relationships do not always bring in new business opportunities, but people may be hesitant to work with a total stranger.”

Table 8 summarizes statistically significant findings resulting from our empirical analysis.

Table 8.

Summary of statistically significant results.

5. Further Investigation

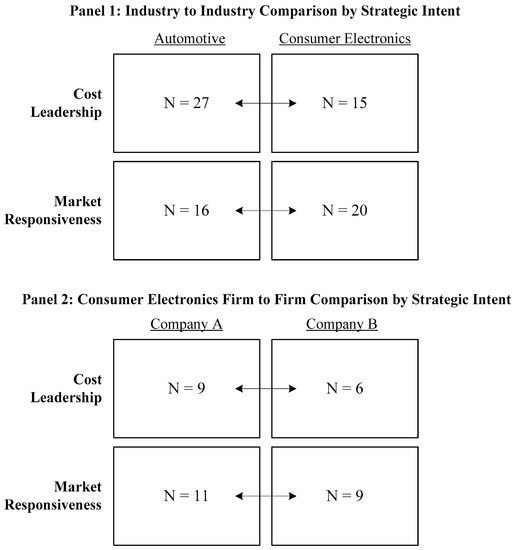

The current study utilized samples from multiple industries and companies. When investigating the supply network design effects of strategic intent, it can be misleading to analyze network data from a single industry or company because of their intrinsic characteristics. Further industry or company wise case comparisons were thus deemed necessary to enrich research findings and yield deeper insights. By dividing the sample by industry and firm, this study explored how the supply network properties corresponding to each strategic intent (either cost leadership or market responsiveness) varied based on: (1) Industries (consumer electronics and automotive) and (2) different OEMs within the same industry (i.e., consumer electronics OEMs, A and B). Figure 3 illustrates this scheme and the sample size for each quadrant. Follow-up interviews on the findings were conducted to offer more practical and meaningful interpretations.

Figure 3.

Framework for further investigation.

5.1. Industry to Industry Comparison

A t-test was employed to analyze each of the four comparison sets in Figure 1 for any significant mean differences with respect to supply network properties. One OEM per each industry was also contacted and asked to share their views and experiences which can provide hints for interpreting the test results. As shown in Table 9, three SNA indices indicated significant mean differences between industries. Specifically, consumer electronics OEMs showed higher values in professional ODC for firms pursuing cost leadership (F = 0.188, p < 0.05) and in contractual IDC those pursuing market responsiveness (F = 0.247, p < 0.05). These findings indicate that, compared to the automotive industry, consumer electronics OEMs have supply networks in which there exist fewer particular focal firms that: (1) Initiate most of the work-related interactions to others (with a cost leadership intent) and (2) have more complete contract terms than others (with a market responsiveness intent). One purchasing manager of a consumer electronics OEM explained these findings:

Table 9.

Panel 1 comparison results.

“I believe the supplier base plays a role here. Compared to automobile manufacturers, consumer electronics OEMs typically have a broader supplier base; thus, we also can more easily probe for potential suppliers who can offer lower prices than the existing ones. Our suppliers may enjoy a similar situation because there are more OEMs in our industry than in the automotive industry. As such, consumer electronics suppliers sometimes behave opportunistically. For instance, one of our former suppliers boasted that they could beat the existing supplier’s price and won the deal. They kept their word … by sacrificing quality! Buyers mostly get what they pay for. In this regard, we keep tight controls on the quality of our sub-components while maintaining lower cost by, as found in your results, initiating more work-related interactions with downstream suppliers. We follow a similar logic when sourcing market responsiveness-focused components. We do not know how responsive our suppliers are likely to be until actual market changes take place on the ground, and thus they can be opportunistic. To deal with this concern, we always try to develop extremely complete contacts specifying every single possible market-related contingency. I believe our suppliers may apply the same policy to their suppliers.”

Table 9 also shows that automotive industry OEMs place a higher value on personal ODC than consumer electronics when they pursue cost leadership (F = 0.005, p < 0.05). In a supply network context, this means that the supply networks of automotive OEMs have fewer particular focal firms which create more non-work-related interactions for other network members. In explaining this observation, an executive-level respondent of an automotive OEM also counted the supplier base as the main source of this difference. He noted:

“I agree with his view—the supplier base makes a big difference. Let me tell you the reason. Of course, we also try to find a supplier which offers the lowest price when we source cost leadership-focused components. One big difference here is the unit price difference between consumer electronics and automobiles; in other words, this industry has more severe consequences for quality problems. This mostly restricts our supplier choice to a shortlist of potential suppliers who previously met our quality requirements or the ones with certain level of quality reputation. Another big difference, I believe, is our understanding of the supply market. We produced most of the components ourselves till about thirty years ago, and our industry change is relatively stable. We therefore do not need to control our suppliers as tightly as consumer electronics OEMs do; rather, we try to develop strong personal ties among supply network members. I personally think Toyota has proven that this approach is quite effective for securing cost leadership while maintaining quality.”

5.2. Firm to Firm Comparison

This study also tested the mean differences of network properties between two consumer electronics OEMs. Pseudonyms (“Company A” and “Company “B”) were used for confidentiality. Both companies have well-established brand names and compete neck and neck in the global consumer electronics market. Company A has a strong market position in Latin American, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian consumer electronics markets, while the primary markets for Company B are North American and European countries. The results in Table 10 provide some interesting observations on those two companies’ differences in supply network properties with respect to strategic intent. Specifically, Company A showed higher values for contractual IDC (F = 2.304, p < 0.10) and professional BTC (F = 0.155, p < 0.05) when it pursued a cost leadership intent. It also had a higher personal ODC value (F = 0.198, p < 0.10) when it pursued market responsiveness. These findings collectively suggest that, compared to Company B, Company A’s supply network has the following characteristics: (1) A particular group of firms possess less favorable contract terms, (2) those particular firms serve as “hubs” for work-related interactions among network members (both pursuing cost leadership), and (3) particular focal firms initiate more non-work-related interactions for other members (pursuing market responsiveness). One executive-level respondent from Company A provided the following interesting explanation:

“Compared to Company B, we are well known for our product localization which provides various product variants in style and features. We have been doing this by slightly modifying the basic product platform. This approach has been quite successful in the fast-growing markets of developing countries where there are few domestic alternatives for us but consumers are sensitive to price at the same time. Consumers in those countries expect to get more than they pay for and, thus, are very demanding on our product quality. When we source cost leadership-focused components used for the basic product platform, we must devise complete contracts to prevent potential opportunistic behaviors of suppliers (which may lead to our higher contractual IDC). Further, to make sure they abide by those contract terms, we are also supposed to be in control of work-related communications among our supply network members (and that may affect the higher professional BTC). Our market responsiveness-focused components are used for localization purposes. As we have a better understanding of the local markets, in this case, we should keep informing our suppliers of potential local market changes to get them prepared to accommodate those changes (which may impact on the high professional ODC value).”

Table 10.

Panel 2 comparison results.

Also shown in Table 10 is that Company B has significantly higher values of contractual GCC (F = 2.869, p < 0.05) in cost leadership intent and professional ODC (F = 0.022, p < 0.10) in market responsiveness intent. These results collectively indicate that: (1) More of its supply network members are directly connected by contract relations when it pursues cost leadership, while (2) there exist particular focal firms who send out most of the work-related interactions to others in the pursuit of market responsiveness. One executive of the company explained these observations by stating that:

“Being different from Company A, we mostly launch ‘global products’ using leading-edge technology, and thus rarely localize our products. As a result, we have had a great success in North America and European continent which are the major battlefields of the global consumer electronics industry. We should gain and protect our technological leadership to keep surviving in those competitive markets because our consumers are ready to pay more for a superior product compared to the ones at emerging markets. I believe all these circumstances may contribute to make the network architectural differences between us and Company A. Even when we source cost leadership-focused components, we focus more on quality-for-money rather than lowest cost per se. Therefore, we maintain extensive control via more complete contracts specifying the required quality level over our non-immediate sub-suppliers as well as tier-1 suppliers. This may be leading to our higher contractual GCC. The components focusing on market responsiveness are the key components with short lifecycles for our final products. When we source those components, it’s best to quickly transfer the technologies we developed to our tier-1 suppliers before they get outdated while preventing any potential leakage or spillover of them. This inevitably creates more technical interventions and surveillance activities on tier-1 suppliers, which may be leading to our high professional ODC.”

6. Discussion

6.1. Contributions

This study made unique theoretical and methodological contributions to the study of supply networks. While there have been significant conceptual developments, there are only a handful of empirical studies investigating a multi-tiered supply network setting (e.g., [33,34,104]). Even those studies have focused on describing the complexity of supply network while remaining in the domain of case-based investigations that require further empirical substantiation. By analyzing the dataset of 153 component-level supply networks consisting of 1852 total network members, this study attempted to shed light on the question, “what determines different supply network architectures,” which has been also recognized by scholars of other disciplines (e.g., [6,53,55]). To address this important unresolved question, the current study adopted the strategic intent perspective on organizational formation which has been widely used in strategic supply chain design studies (e.g., [11,88]) to argue that different products require different supply chains. The results from our social network analyses and MNL models provided significant empirical evidence that supply networks have discernible architectural properties according to a specific strategic intent (either cost leadership or market responsiveness). Further field investigations were conducted to support and interpret the preceding statistical findings. The in-depth follow-up interviews confirmed that supply network members consistently implement certain practices based on their own rational judgments, which consequently lead to the supply network properties found in the study. Taken together, this study suggests that a supply network should be viewed as a systematic outcome which is intentionally and strategically designed, implemented, and maintained in service with the OEM’s strategic intent(s).

This study also further developed, as well as contradicted, the theory of the supply network as a complex adaptive system (CAS). In their seminal paper on CAS theory, Choi et al. [93] conceptually regarded a supply network as an “emerging” form in that: (1) One single network actor cannot completely control the entire supply network and (2) too much control deteriorates innovation and flexibility outcomes. In this vein, the authors defined CAS as “a system that emerges over time into a coherent form, and adapts and organizes itself without any singular entity deliberately managing or controlling it” [93], (p. 352). The current study empirically shows what “coherent” supply network properties had emerged under the OEM’s consideration of a specific strategic intent instead of arguing a deterministic view of supply network architecture. Acknowledging the cross-sectional nature of the data, however, the empirical findings here also cast doubt on the conceptual propositions of CAS theory. As clearly seen in the responses from follow-up interviews, each supply network actor reacted to their immediate customers and suppliers by relying on their own rational assessment of potential costs and benefits of accepting or imposing a strategic intent on their counterparts. The empirical findings of this study thus can be regarded as the architectural outcomes of supply networks resulting from each network actor’s continued self-centered perception and behavior reinforced by their counterparts’ intents. From a managerial standpoint, the current study also provides useful guidance for understanding direct or indirect relationships across multiple tiers in the supply network. Based on the found network properties, supply network managers can infer: (1) How their immediate and non-immediate partners work together (or often against one another) in pursuing common (or sometimes incompatible) interests, and (2) whether the homogeneity (or heterogeneity) among supply network members would help or hinder the OEM’s ability to achieve the strategic intent of the sourced component. It also can enable open collaboration across firm boundaries by allowing them to freely discuss the extent to which each type of network tie should be: (1) Orchestrated by hub firms (with BTC), (2) gained from and disseminated to others (with IDC and ODC), and (3) connected with one another (with GCC) to achieve different strategic intents. All the findings of this study were further corroborated and extended by in-depth follow-up field investigations and interviews with the supply chain professionals.

In addition, this study was one of few attempts to adopt a concept of network multiplexity by considering multiple types of network ties to examine supply network phenomena. Adding to the traditional visible ties (contractual and transactional ties), invisible dimensions (professional and personal ties) were accounted for in the description of supply network architecture. This enabled a more thorough articulation of supply network architecture, which is essential for drawing more meaningful conclusions about the association between strategic intents and supply network properties. A series of social network analyses confirmed the multiplex traits of supply networks by showing that a given supply network comprised of the same set of firms can be perceived differently based on different tie types with different directions and strengths. This can provide a theoretical foundation to reexamine buyer-seller relationships and confirm that theories based on a uniplex perspective still hold for other types of interfirm ties.

Lastly, the current study adopted directed valued network and whole network approaches. The directed valued network approach has definite advantages in grasping network phenomena by considering both the directions and the strengths of network ties, whereas the widely-used binary network approach relies on an unrealistic premise that all ties are completely homogeneous and symmetrical [58,59]. In addition, for the sake of saving time and effort on network data collection, many social network studies have taken an ego network approach that considers one single network actor and a set of directly linked neighbors. This approach, however, has serious methodological limitations for analyzing supply networks in that: (1) It considers a focal network actor’s perceptions only [105,106] and (2) a clear determination of supply network boundary is almost impossible [93,107]. Therefore, this study adopted a whole network approach collecting bidirectional responses stretching from one network actor to its raw materials suppliers, which has been repeatedly recommended as the most desirable approach for examining supply networks [53,108]. Taken together, this study tried to draw the most complete outline of supply network phenomena by adopting a new, more realistic, and rigorous network approach.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study was not without limitations. First, the strategic intents and supply network tie types considered in this research were not exhaustive. Although Fisher’s [11] considerations appear an one of the most highly cited papers on supply chain design, future studies may incorporate more component-level strategic intents not represented by Fisher’s framework. Innovation-focused components, for instance, can be taken into consideration because it occasionally focuses on both lower cost (in case of incremental innovation) and responsiveness (in case of radical innovation) intents. In this vein, knowledge sharing often measured by customer- and supplier-specific research and development investments can be considered as an additional supply network tie type. Second, this study used cross-sectional network data in describing supply network properties because of a longitudinal dataset was not available. Access to secondary data sources may allow for more generalizable findings on the associations between strategic intents and network properties, even though obtaining data for the whole network will sacrifice sample size. A potential remedy for this challenge is carrying out the same data collection procedure with the original respondents after a certain time period and conducting an event study analysis on abnormal changes in network properties. Another option is to target industries such as information technology, software, or fashion with relatively shorter industry clockspeeds and check whether the changed network properties remain changed or get restored to the original states. Use of longitudinal dataset also can extend our knowledge of how the multiplex nature of supply networks evolves starting one or two dominant network tie type(s). For instance, family firms may be more likely to start with stronger personal ties and build other ties as they grow in size. It will also be an interesting topic for future research to explore the contingencies (other than ownership status) that affect the multiplex nature of supply networks. Lastly, scholars in organization theory and strategic management have argued that interfirm networks consisting of direct and indirect relations with other firms systematically affect a firm’s competitive advantage. An interesting extension of this study would be to examine the performance implications (e.g., financial gains, innovation, etc.) of supply network architecture.