Electronic Activation and Inhibition of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Catalyzed by a Complex Heterologous Membrane-Bound Complex

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Latex Collection from Ficus elastica

2.2. Ficus elastica Washed Rubber Particle Preparation

2.3. Rubber Particle Preservation

2.4. Siliconization of Reaction Tubes

2.5. Rubber Transferase Reactions Under Static Metal Ion Control

2.6. Electrode Fabrication

2.7. Programmable Chemical Actuator Fabrication

2.8. Polypyrrole Polymerization

2.9. Polypyrrole Equilibration

2.10. PCA Operation

2.11. PCA-Controlled Rubber Transferase Reactions

2.12. Scintillation Counting

2.13. Molecular Weight Determination

2.14. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rubber Biosynthesis Under Static Control

3.1.1. Rubber Initiation Is Unaffected by Divalent Metal Cation Under Static Control

3.1.2. Rubber Elongation Is Unaffected by Divalent Metal Cation Under Static Control

3.1.3. Rubber Molecular Weight Is Dependent upon Divalent Metal Cation Under Static Control

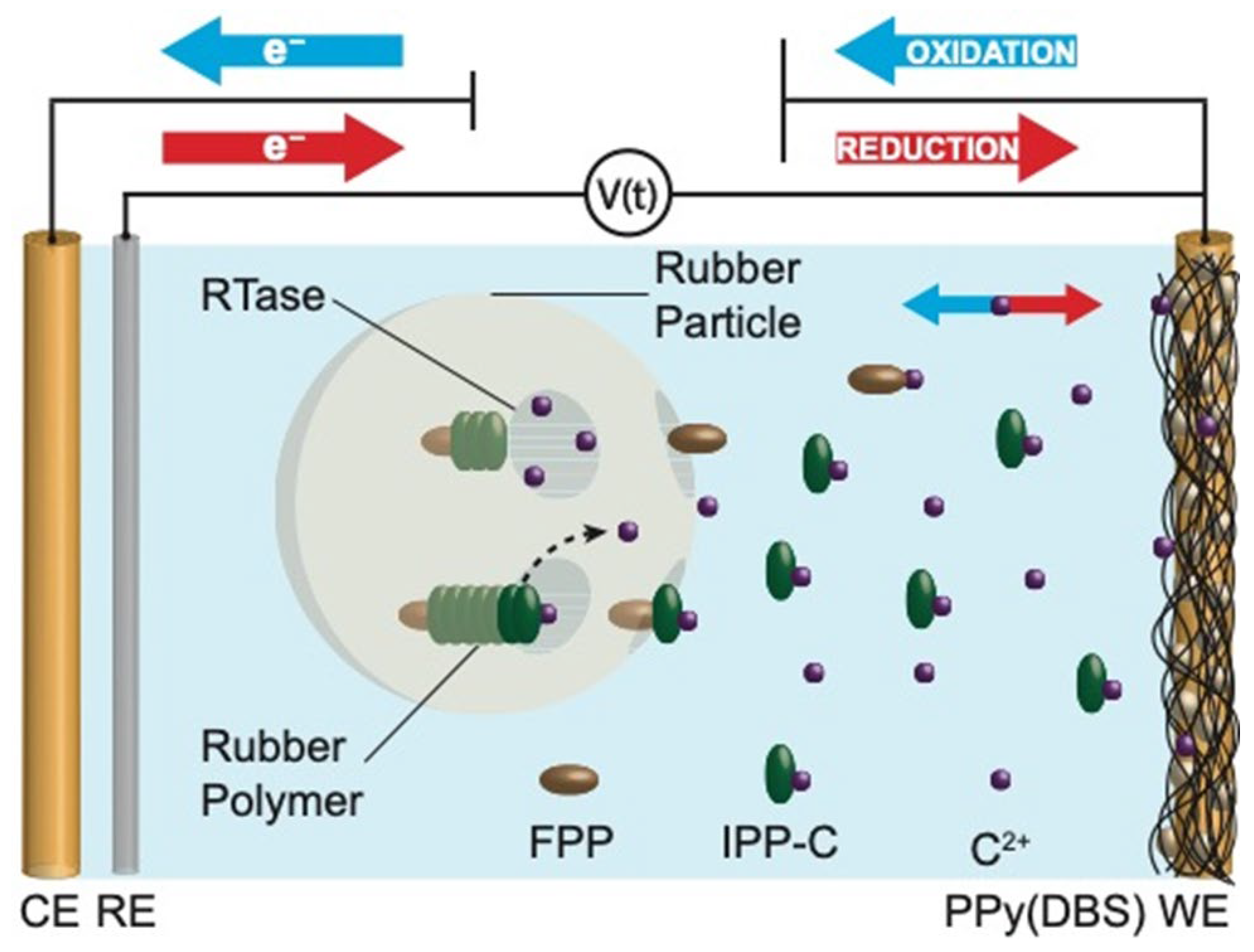

3.2. Programable Chemical Actuator Control of Rubber Biosynthesis

3.2.1. PCAs Change Ion Concentration Without Solution Exchange

3.2.2. Rubber Biosynthesis Under Reduction Control

3.2.3. Rubber Biosynthesis Under Oxidation Control

3.2.4. Rubber Biosynthesis Under Mixed Reduction and Oxidation Control

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APP | Allylic pyrophosphate |

| DBS | Dodecyl benzene sulfonate |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FPP | Farnesyl pyrophosphate |

| Mg2+ | Magnesium cations |

| Mn2+ | Manganese cations |

| IPP | Isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| PCA | Programable Chemical Actuator |

| PPy | Polypyrolidone |

| RTase | Rubber transferase enzyme complex |

References

- Cornish, K. Alternative natural rubber crops: Why should we care? Technol. Innov. 2017, 18, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K. Similarities and differences in rubber biochemistry among plant species. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, K.; Blakeslee, J.J. Rubber Biosynthesis in Plants; American Oil Chemist Society, The Lipid Library: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011; Available online: http://lipidlibrary.aocs.org/plantbio/plantlip.html (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Cherian, S.; Ryu, S.B.; Cornish, K. Natural rubber biosynthesis in plants, the rubber transferase complex, and metabolic engineering progress and prospects. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 2041–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Men, X.; Wang, F.; Chen, G.-Q.; Zhang, H.-B.; Xian, M. Biosynthesis of natural rubber: Current state and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeslee, J.J.; Han, E.-H.; Lin, Y.; Lin, J.; Nath, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Cornish, K. Proteomic and targeted lipidomic analyses of fluid and rigid rubber particle membrane domains in guayule. Plants 2024, 13, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siler, D.J.; Goodrich-Tanrikulu, M.; Cornish, K.; Stafford, A.E.; McKeon, T.A. Composition of rubber particles of Hevea brasiliensis, Parthenium argentatum, Ficus elastica and Euphorbia lactiflua indicates unconventional surface structure. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1997, 35, 881–889. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.F.; Cornish, K. Microstructure of purified rubber particles. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2000, 161, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Wood, D.F.; Windle, J.J. Rubber particles from four different species, examined by transmission electron microscopy and electron paramagnetic resonance spin labeling, are found to consist of a homogeneous rubber core enclosed by a contiguous, monolayer biomembrane. Planta 1999, 210, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Siler, D.; Grosjean, O.; Goodman, N. Fundamental similarities in rubber particle architecture and function in three evolutionarily divergent plant species. J. Nat. Rubber Res. 1993, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, B.; Scott, D.J.; McMahan, C.M.; Shintani, D.K.; Cornish, K. Rubber accumulation and rubber transferase activity during root development of Taraxacum kok-saghyz dandelion. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Xie, W. Natural rubber biosynthesis in plants: Rubber transferase. Methods Enzymol. 2012, 515, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K. Biochemistry of natural rubber, a vital raw material, emphasizing biosynthetic rate molecular weight and compartmentalization, in evolutionarily divergent plant species. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.J.; da Costa, B.M.T.; Espy, S.C.; Keasling, J.D.; Cornish, K. Activation and inhibition of rubber transferases by metal cofactors and pyrophosphate substrates. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Siler, D.J. Characterization of cis-prenyl transferase activity localised in a buoyant fraction of rubber particles from Ficus elastica latex. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1996, 34, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Espy, S.C.; Keasling, J.D.; Castillón, J.; Cornish, K. Initiator-independent and initiator-dependent rubber biosynthesis in Ficus elastica. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 448, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillón, J.; Cornish, K. Regulation of initiation and polymer molecular weight of cis-1, 4-polyisoprene synthesized in vitro by particles isolated from Parthenium argentatum (Gray). Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.M.; Keasling, J.D.; McMahan, C.M.; Cornish, K. Magnesium ion regulation of in vitro rubber biosynthesis by Parthenium argentatum Gray. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, B.M.; Keasling, J.D.; Cornish, K. Regulation of rubber biosynthetic rate and molecular weight in Hevea brasiliensis by metal cofactor. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Cornish, K.; McMahan, C.M.; Whalen, M.C.; Shintani, D.K.; Coffelt, T.A.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Magnesium affects rubber biosynthesis and particle stability in Ficus elastica, Hevea brasiliensis and Parthenium argentatum. In New Crops: Bioenergy, Biomaterials, and Sustainability, Proceedings of the Joint Annual Meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Industrial Crops and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 October 2013; Janick, J., Whipkey, A., Cruz, V.M., Eds.; ASHS Press: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bisswanger, H. Enzyme assays. Perspect. Sci. 2014, 1, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naro, Y.; Darrah, K.; Deiters, A. Optical control of small molecule-induced protein degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2193–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segel, I. Enzyme Kinetics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, P.; Marques, M.P.; Sulzer, P.; Wohlgemuth, R.; Mayr, T.; Baganz, F.; Szita, N. Realtime pH monitoring of industrially relevant enzymatic reactions in a microfluidic side-entry reactor (μSER) shows potential for pH control. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 12, 1600475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagel, H.; Bier, F.; Frohme, M.; Glökler, J.F. A novel optical method to reversibly control enzymatic activity based on photoacids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, T.; Deiters, A. Optical control of protein phosphatase function. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Fridriksdottir, A.; Alkhairi, O.; Sepunaru, L. Electrochemical investigation of enzyme kinetics with an unmediated, unmodified platinum microelectrode: The case of glucose oxidase. ACS Electrochem. 2025, 1, 1722–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadhim, M.J.; Gamaj, I. Estimation of the diffusion coefficient and hydrodynamic radius (Stokes radius) for inorganic ions in solution depending on molar conductivity as electro-analytical technique—A review. J. Chem. Rev. 2020, 2, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, R.; Martinez, J.; Keskula, A.; Anbarjafari, G.; Aabloo, A.; Otero, T. Polymeric actuators: Solvents tune reaction-driven cation to reaction-driven anion actuation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 233, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Fenton, A. Divalent cations in human liver pyruvate kinase exemplify the combined effects of complex-equilibrium and allosteric regulation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Cornish, K. Programmable Chemical Actuator Control of Soluble and Membrane-Bound Enzymatic Catalysis. In Methods in Enzymology; Biochemical Pathways and Environmental Responses in Plants: Part A; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 676, pp. 159–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadki, S.; Schottland, P.; Brodie, N.; Sabouraud, G. The mechanisms of pyrrole electropolymerization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyoda, T.; Ohtani, A.; Shimidzu, T.; Honda, K. Charge-controllable membrane. polypyrrole-polyelectrolyte composite membrane through anodic doping process. Chem. Lett. 1986, 15, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Adeloju, S.; Wallace, G. In-situ electrochemical studies on the redox properties of polypyrrole in aqueous solutions. Eur. Polym. J. 1999, 35, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hery, T.M.; Satagopan, S.; Northcutt, R.G.; Tabita, F.R.; Sundaresan, V.-B. Polypyrrole membranes as scaffolds for biomolecule immobilization. Smart Mater. Struct. 2016, 25, 125033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Sundaresan, V.B. Polypyrrole-based amperometric cation sensor with tunable sensitivity. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struc. 2016, 27, 1702–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Hery, T.; Venkatesh, V.; Sundaresan, V.B. Mass and charge density effects on the saturation kinetics of polypyrrole doped with dodecylbenzene sulfonate. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2017, 28, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ghatak, S.; Hery, T.; Khanna, S.; El Masry, M.; Sundaresan, V.B.; Sen, C.K. Ad-hoc hybrid synaptic junctions to detect nerve stimulation and its application to detect onset of diabetic polyneuropathy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hery, T.; Sundaresan, V.-B. Ionic redox transistor from pore-spanning ppy (dbs) membranes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Siler, D.J.; Grosjean, O.K. Immunoinhibition of rubber particle-bound cis-prenyl transferases in Ficus elastica and Parthenium argentatum. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, K.; Bartlett, D.L. Stabilisation of particle integrity and particle bound cis-prenyl transferase activity in stored, purified rubber particles. Phytochem. Anal. 1997, 8, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Otero, J.J.; Sundaresan, V.B.; Czeisler, C.M. Near field non-invasive electrophysiology of retrotrapezoid nucleus using amperometric cation sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 151, 111975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, S.J.S.; Pachauri, V. Chelation in metal intoxication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2745–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, M.; Landolt, D. Experimental investigation of mass transport in pulse plating. Surf. Technol. 1985, 25, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathna, S.; Clark, T.; Bae, C.; Kil, E.; Bang, A.; Sy, M.; Yeh, R.; Feng, K. Copper electroplating processes for advanced HDI applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 14th International Microsystems, Packaging, Assembly and Circuits Technology Conference (IMPACT), Taipei, Taiwan, 23–25 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.; Roy, S. Application of a duplex diffusion layer model to pulse reverse plating. Trans. IMF 2017, 95, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidou, M.; Tybrandt, K.; Berggren, M.; Simon, D.T. Overcoming transport limitations in miniaturized electrophoretic delivery devices. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R.; Leddy, J.; Zoski, C.G. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Funt, B.; Diaz, A. Organic Electrochemistry: An Introduction and a Guide; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, V.; Venkatesh, V.; Northcutt, R.G.; Maddox, J.; Sundaresan, V.B. Nanoscale polypyrrole sensors for near-field electrochemical measurements. Sen. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 242, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V. Kinetics of Ion Transport in Conducting Polymers. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt, R.G. A Mechanistic Interpretation for Charge Storage in Conducting Polymers. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, V.; Zhang, H.; Northcutt, R.; Sundaresan, V.B. A thermodynamic chemomechanical constitutive model for conducting polymers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 201, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacka-Wojcik, I.; Huerta, M.; Tybrandt, K.; Karady, M.; Mulla, M.Y.; Poxson, D.J.; Gabrielsson, E.O.; Ljung, K.; Simon, D.T.; Berggren, M.; et al. Implantable organic electronic ion pump enables aba hormone delivery for control of stomata in an intact tobacco plant. Small 2019, 15, 1902189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahalianov, I.; Singh, S.K.; Tybrandt, K.; Berggren, M.; Zozoulenko, I. The intrinsic volumetric capacitance of conducting polymers: Pseudo-capacitors or double-layer supercapacitors? RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 42498–42508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strakosas, X.; Seitanidou, M.; Tybrandt, K.; Berggren, M.; Simon, D.T. An electronic proton-trapping ion pump for selective drug delivery. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noolandi, J.; Turmel, C. Elastic bag model of one-dimensional pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (ODPFGE). In Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis: Protocols, Methods, and Theories; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 451–467. [Google Scholar]

- Marafi, M.; Rana, M.S. Role of EDTA on metal removal from refinery waste catalysts. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 231, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Evans, J.P.; Sundaresan, V.B.; Cornish, K. Electronic Activation and Inhibition of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Catalyzed by a Complex Heterologous Membrane-Bound Complex. Processes 2026, 14, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020374

Evans JP, Sundaresan VB, Cornish K. Electronic Activation and Inhibition of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Catalyzed by a Complex Heterologous Membrane-Bound Complex. Processes. 2026; 14(2):374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020374

Chicago/Turabian StyleEvans, J. Parker, Vishnu Baba Sundaresan, and Katrina Cornish. 2026. "Electronic Activation and Inhibition of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Catalyzed by a Complex Heterologous Membrane-Bound Complex" Processes 14, no. 2: 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020374

APA StyleEvans, J. P., Sundaresan, V. B., & Cornish, K. (2026). Electronic Activation and Inhibition of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Catalyzed by a Complex Heterologous Membrane-Bound Complex. Processes, 14(2), 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020374