3.2. The Effect of Pressure on the Breakdown Process

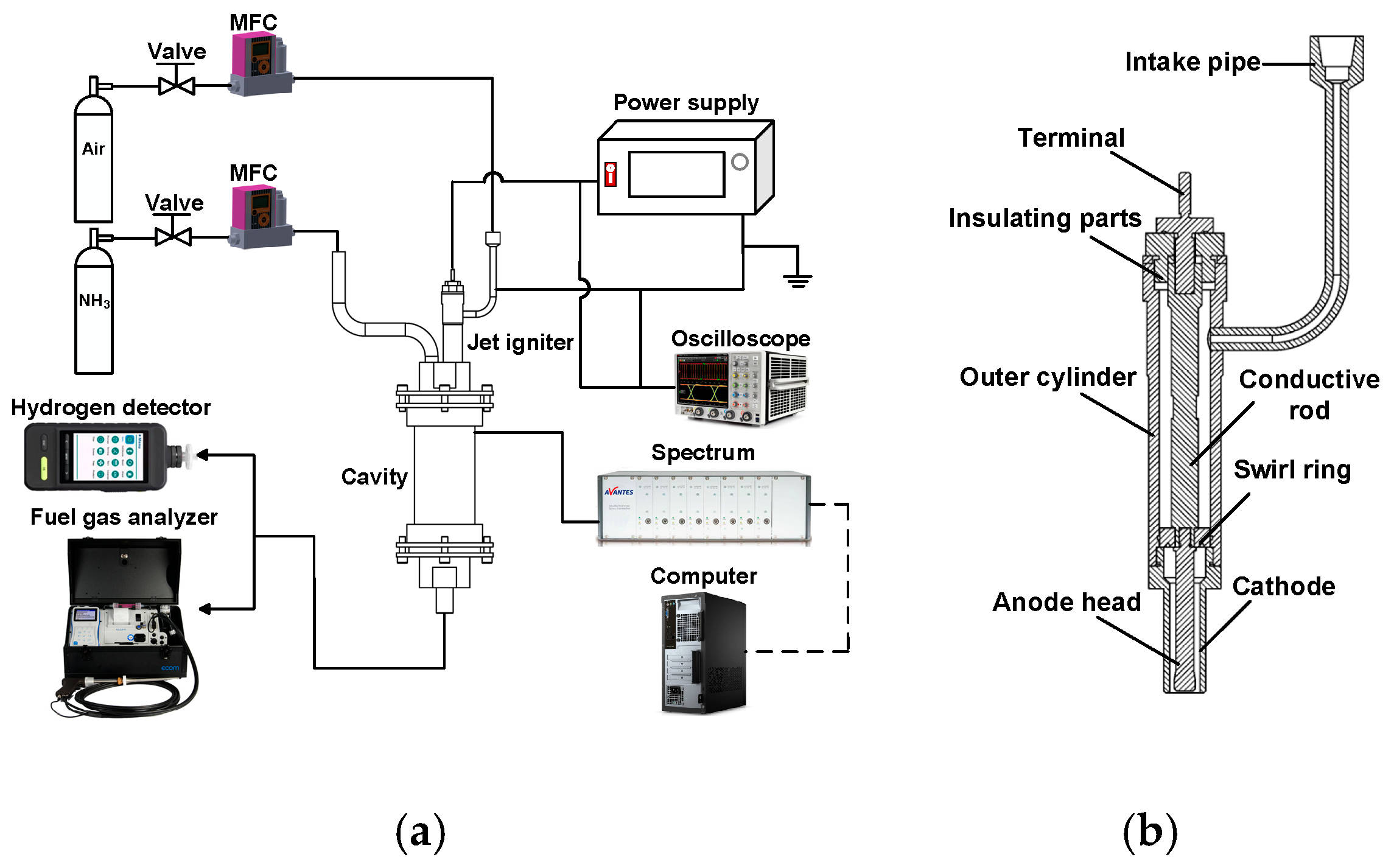

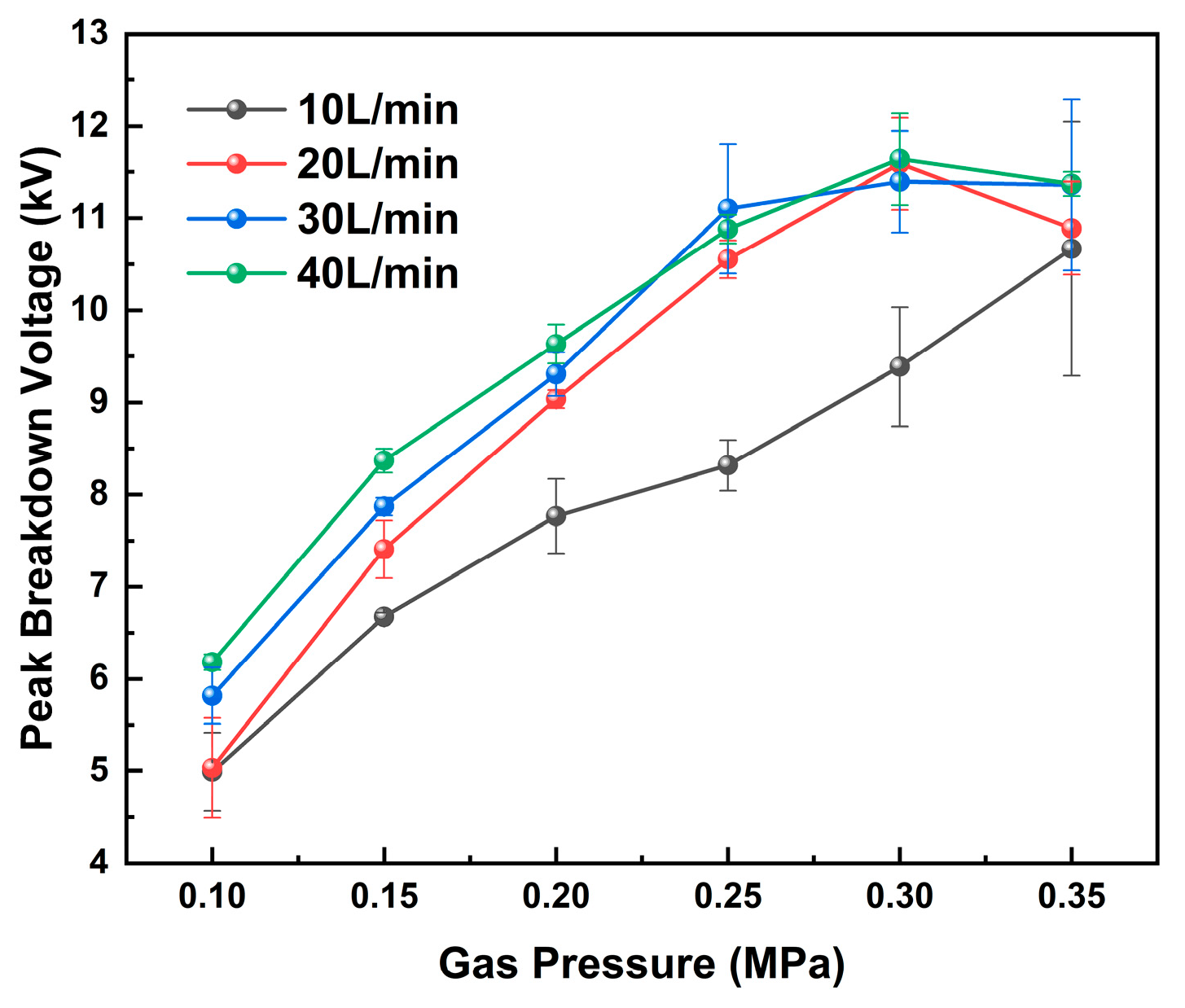

To evaluate the influence of pressure on the breakdown characteristics, the peak breakdown voltage was measured under different pressure conditions, as shown in

Figure 3. It is evident that the breakdown voltage increases monotonically with increasing pressure. At an air flow rate of 10 L/min, the peak breakdown voltage increases from 4.99 kV to 10.67 kV as pressure increases.

The increasing trend of breakdown voltage with pressure can be explained from the perspectives of electric field intensity and electron collision physics. In gas discharges, the electron mean free path (

) is commonly given by:

where

is the gas number density, and

is the effective electron–neutral collision cross section. In the context of gas discharge and plasma analysis, the gas number density

can be expressed as follows:

where

is the gas pressure,

is the Boltzmann constant, and

is the gas temperature. By combining Equations (1) and (2), it follows that the electron mean free path is inversely proportional to the gas pressure. As pressure increases, the electron mean free path decreases, thereby reducing the energy gained by electrons between successive collisions. To satisfy the ionization condition, a higher electric field intensity is therefore required, leading to an increase in the breakdown voltage.

This trend is consistent with the qualitative description of Paschen’s law. According to Paschen’s law and streamer discharge theory [

22], for a given electrode gap, the breakdown voltage typically exhibits a U-shaped dependence on the product of pressure and gap distance (

value). As the

value increases, the breakdown voltage initially decreases, reaches a minimum, and then increases. Paschen’s law expresses the breakdown voltage

as follows:

where

is the electrode gap distance (2 mm).

and

are gas-specific constants, and

is the secondary electron emission coefficient. For air, the commonly used values of the Paschen constants

and

are

and

, and

. In the present experiments, the investigated

range (200–800 Pa·m) is much greater than the Paschen minimum for air (

Pa·m). The operating conditions fall on the right-hand side of the Paschen curve, where an increasing breakdown voltage with increasing

is generally expected, which agrees with the observed trend. Taking an air flow rate of 10 L/min as an example, the breakdown voltage calculated based on Paschen’s law is approximately 8.8 kV at 0.1 MPa and increases to about 28.9 kV at 0.4 MPa. These theoretical values are much higher than the experimentally measured breakdown voltages. This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors. Paschen’s law is derived under the assumption of a uniform electric field and a static gas environment, whereas the present plasma jet ignition configuration involves a highly non-uniform electric field and a strong gas flow. The convective transport associated with the jet flow enhances heat and charged-particle losses, thereby increasing the effective breakdown threshold.

In addition to pressure, the effect of gas flow rate on breakdown voltage was also examined. During the breakdown voltage measurements, the air flow rate was varied from 10 to 40 L/min. The results indicate that the peak breakdown voltage increases with increasing gas flow rate.

As the gas flow rate increases, a distinct shear layer develops between the high-velocity jet core and the surrounding quiescent or low-velocity gas, leading to enhanced velocity gradients and flow instabilities in that region [

23,

24]. Within the shear-dominated region, the intensified turbulence promotes both thermal convection and the transport of charged and reactive species [

25], effectively redistributing the deposited electrical energy over a larger volume. As a result, local gas temperature gradients are reduced, and the plasma channel tends to broaden, causing a more spatial distribution of current density. This process inhibits current constriction and weakens the local electric field enhancement within the discharge channel. Consequently, a higher applied voltage is required to initiate breakdown in order to compensate for the reduced effective ionization efficiency and increased convective losses [

26].

3.3. The Effect of Pressure on the Arc-Sustaining Process

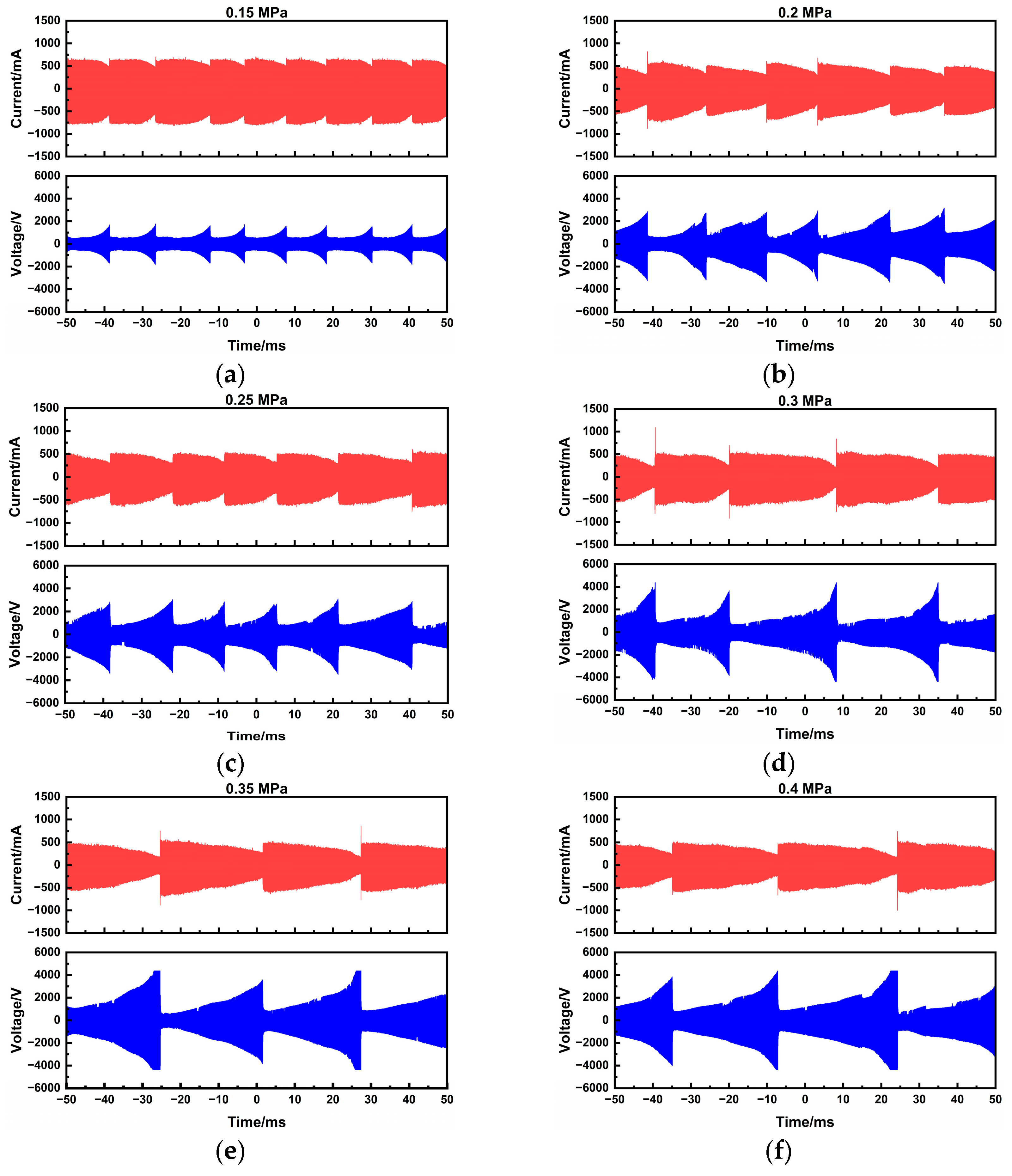

To systematically evaluate the arc-sustaining process of the plasma-assisted ammonia jet flame ignitor, voltage–current characteristics were measured at a fixed power supply setting of 180 W and 20 kHz, with chamber pressure varying from 0.1 to 0.4 MPa. Waveforms were recorded over a 100 ms duration using a digital oscilloscope, as summarized in

Figure 4.

Although the general trends in discharge voltage and current remain consistent with those observed at atmospheric pressure, increasing the chamber pressure raises the gas density. This higher density increases the resistance to arc motion, resulting in a noticeable reduction in the arc sliding speed even at a constant gas flow rate of 10 SLM. Moreover, increased pressure causes arc contraction and enhances energy dissipation, rendering the arc less deformable and more difficult to sustain in motion, which ultimately lowers the sliding frequency. The peak discharge voltage also increases significantly with pressure, rising from 1.8 to 2.2 kV at 0.1 MPa to 3.0–4.5 kV at 0.4 MPa.

Since breakdown voltage is often associated with statistical uncertainty, to characterize the overall trend of discharge voltage and current amid the inherent stochasticity of arc discharge, the average values over a 100 ms discharge duration were calculated using the following formula:

where

is the average power,

and

are the instantaneous voltage and current,

and

define the discharge interval, and

is the recorded discharge duration.

Figure 5 shows the average discharge voltage and current of the plasma jet ignitor under varying pressure and flow conditions. At a flow rate of 10 SLM, the average voltage increases from 360 V to 514 V as pressure rises from 0.1 to 0.4 MPa, while the current decreases from 185 mA to 95 mA. This behavior is consistent with the breakdown process. As pressure increases, the number density of gas molecules rises, shortening the electron mean free path. A shorter mean free path limits the energy electrons gain from the electric field, reducing their ability to ionize gas molecules through collisions. Consequently, a higher voltage is required to sustain the discharge at the same electrode gap.

The average discharge power at different pressures is illustrated in

Figure 4c. It can be observed that during the discharge process, the actual average power remains in the range of 100–120 W, showing no significant dependence on increasing chamber pressure. This is primarily attributable to the output characteristics of the power supply. Throughout the discharge process, the power supply was set to maintain a constant output of 180 W. As the chamber pressure increased, the voltage increased and the current decreased correspondingly, resulting in a roughly constant average discharge power.

3.4. The Effect of Pressure on Spectral Characteristics

The fundamental principle of optical emission diagnostics lies in the photon emission from excited-state particles generated during plasma discharge. Each particle type possesses a unique set of energy levels, resulting in a characteristic “fingerprint” spectrum. Analyzing this emission from a gliding arc discharge, therefore, permits the determination of the plasma’s chemical composition and the states of its constituents, forming a critical basis for probing underlying reaction kinetics and ignition mechanisms.

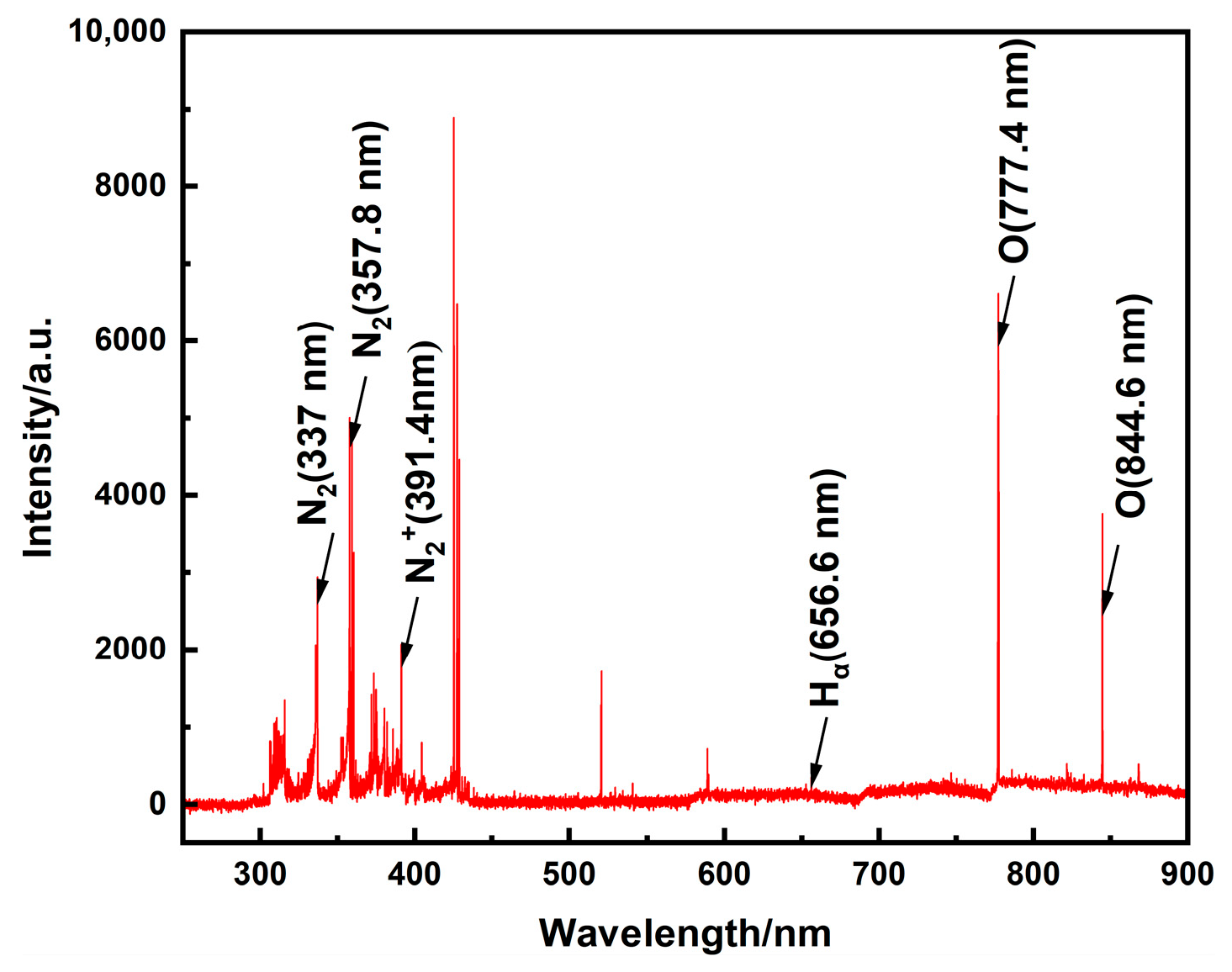

A typical emission spectrum of the gliding arc discharge under atmospheric pressure is presented in

Figure 6. When operating with air as the working gas (without ammonia ignition), the plasma-assisted ammonia jet flame ignitor emission is primarily distributed between 300 nm and 850 nm. The spectral lines within the 350–450 nm range exhibit higher intensity. Characteristic lines from nitrogen species and oxygen atoms are identified, including the Second Positive System N

2 (C

2Π

u → B

2Π

g) bands at 337.1 nm and 357.8 nm, and the First Negative System of N

2+ (B

2Σ

u+ → X

2Σ

g+) at 391.4 nm, and atomic oxygen lines at 777.4 nm and 844.6 nm. As oxygen atoms act as crucial catalysts in combustion, their spectral presence serves as a key indicator for assessing the efficacy of the plasma-assisted ammonia jet flame ignitor. These results demonstrate that plasma-assisted ignition provides a substantial quantity of excited molecules, particles, and free radicals. These highly reactive species facilitate subsequent combustion chemical reactions, thereby enhancing the overall ignition and combustion performance.

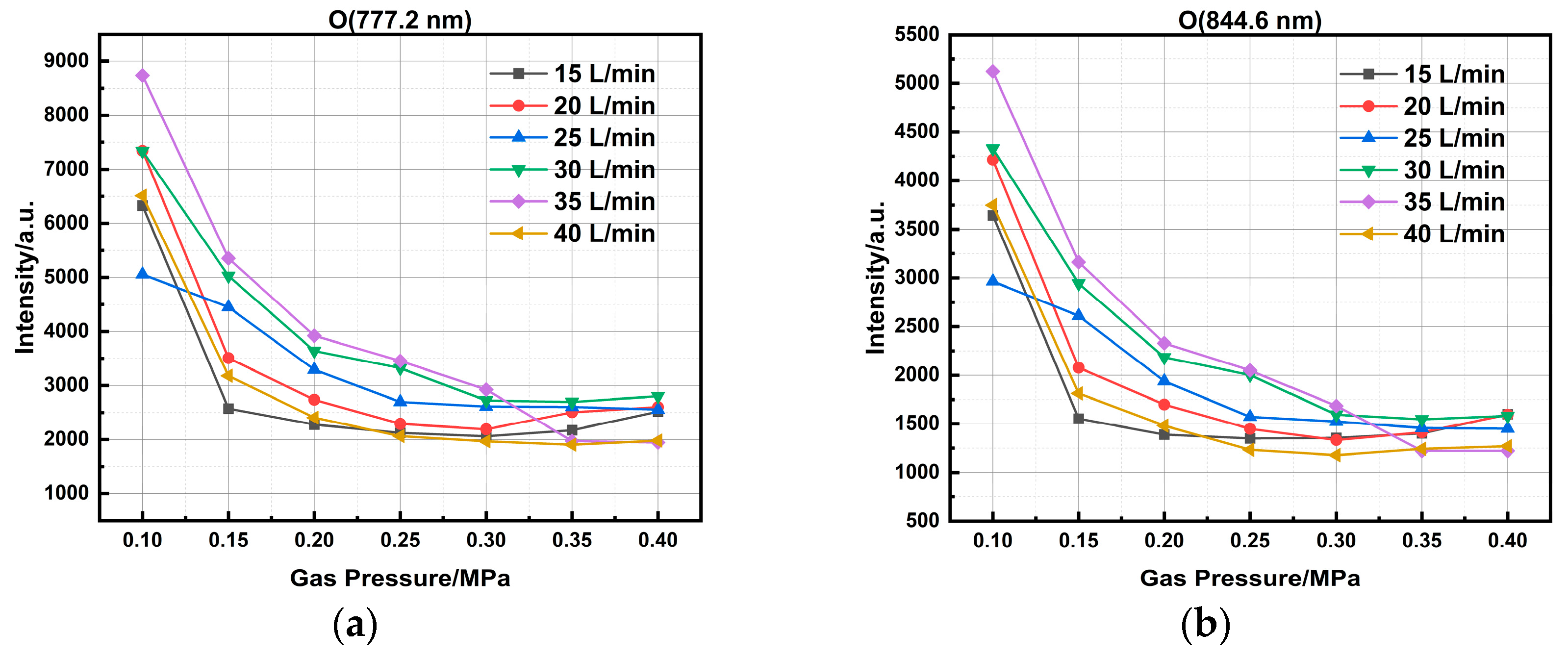

To investigate the effect of pressure on the emission spectra, measurements were conducted at various pressure conditions with an air flow rate ranging from 10 to 40 SLM. As shown in

Figure 7, the emission intensity of oxygen atomic lines declines with increasing chamber pressure. The attenuation is primarily attributed to two factors. First, higher pressure increases gas density, which shortens the electron mean free path and reduces the energy electrons gain from the electric field, thereby decreasing the population of high-energy electrons available for exciting oxygen atoms. Second, the higher gas density promotes collisional quenching of excited oxygen atoms, a non-radiative process that competes with and increasingly dominates over radiative transitions as pressure rises, thus reducing the probability of photon emission.

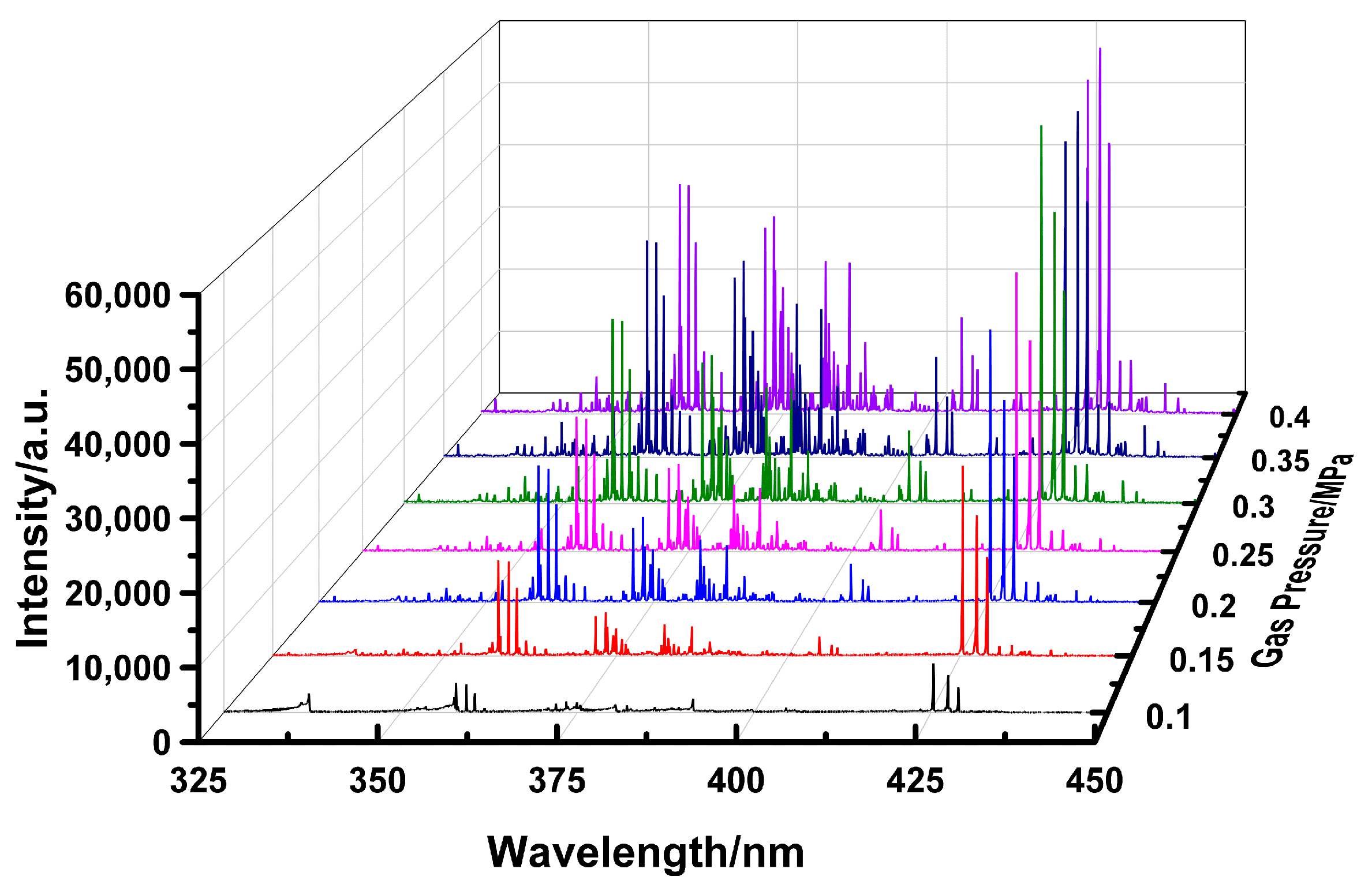

The pressure dependence of nitrogen band emission is displayed in

Figure 8. Both the emission intensity and the spectral density of nitrogen molecular bands in the 350–450 nm range increase markedly with rising chamber pressure. A quantitative measure is provided by the N

2 Second Positive Band at 357.8 nm. The intensity increases from 4027.15 a.u. to 36,008.23 a.u., representing an approximately 8-fold enhancement over the investigated pressure range. Two interrelated mechanisms explain these observations. Firstly, increased gas density enhances the collision frequency between charged particles and neutral N

2 molecules, leading to a higher rate of excitation and thus greater emission intensity. Secondly, the same increase in density promotes collisional broadening, which merges adjacent rotational–vibrational lines.

To assess the practical implications for ignition, spectra were captured during ammonia combustion at φ = 0.6 under various pressures, as shown in

Figure 9. Similar to the spectral evolution observed in air discharge, the emission intensities of the oxygen atomic lines at 777.4 nm and 844.6 nm decreased significantly with increasing chamber pressure, while the nitrogen-dominated emission in the 350–450 nm range is simultaneously enhanced. This consistent trend underscores the general influence of pressure on the plasma’s radiative properties, regardless of the presence of ammonia.

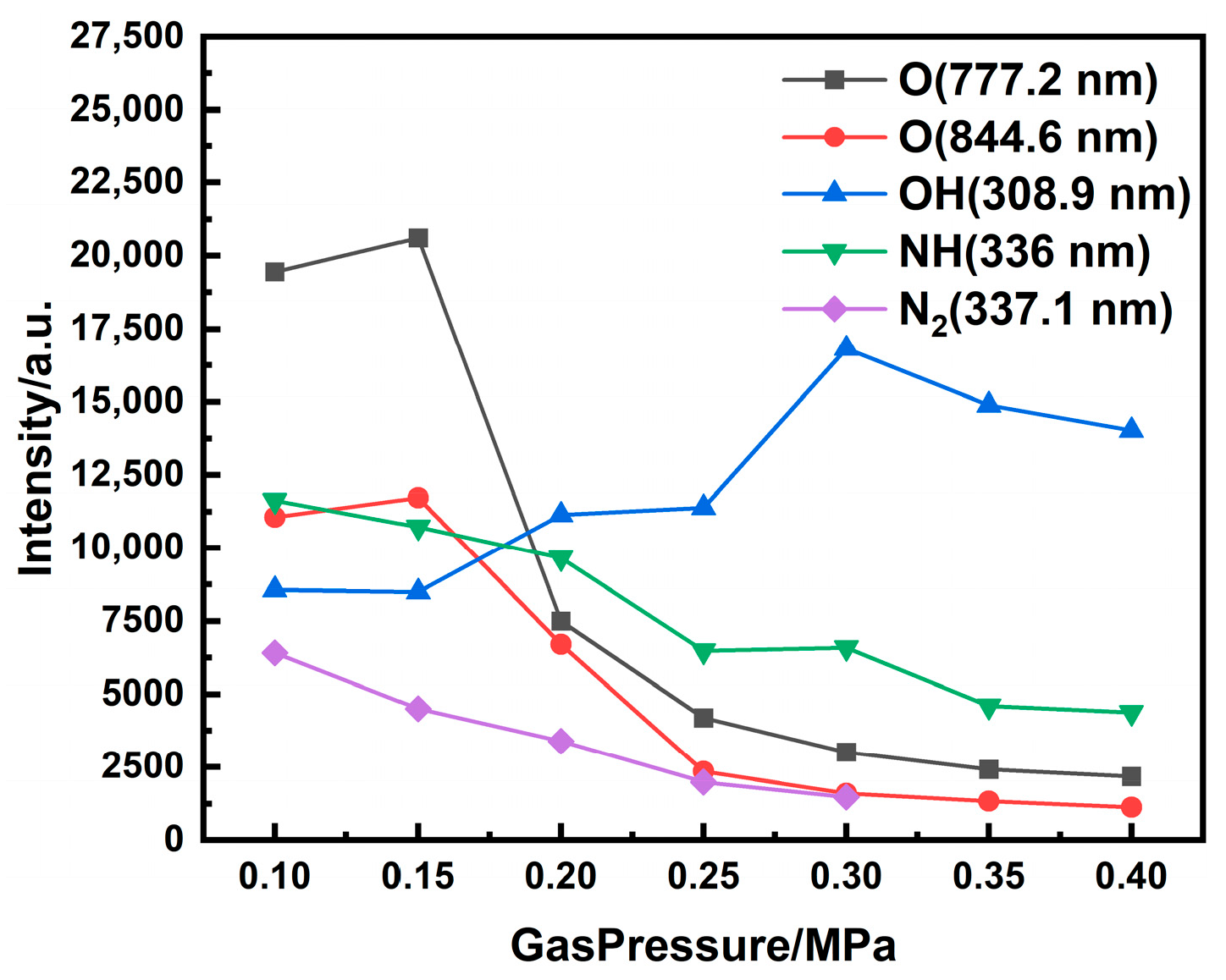

The pressure-dependent emission spectra from ammonia combustion at φ = 0.6 are displayed in

Figure 9. Analysis focuses on NH and H emission, as these species are direct indicators of ammonia decomposition. As shown in

Figure 10, the H

α line is observable only up to 0.25 MPa, beyond which its intensity declines by about 80%. This attenuation is attributed to the excitation mechanism of the H

α line, which originates from the collisional excitation of hydrogen atoms by high-energy electrons. Higher pressure drastically reduces the mean electron energy and the high-energy tail of the electron energy distribution function. Furthermore, the increased gas density promotes collisional quenching of excited H atoms, a non-radiative de-excitation pathway that successfully competes with photon emission, resulting in line broadening and diminished peak intensity. The emission intensity of the NH radical follows a comparable trend, decreasing from 11,628.5 a.u. to 4387.6 a.u. with increasing pressure. This consistent reduction in the signal from both primary decomposition products suggests that higher cavity pressure inhibits the overall ammonia decomposition rate under the studied lean condition.

In plasma diagnostics, the electron excitation temperature serves as a crucial indicator of energy exchange efficiency between electrons and heavy particles. The sliding arc plasma generated by the jet igniter, while inherently non-equilibrium, is commonly treated under the local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) approximation. Within an LTE region, the population densities of different energy levels obey the Boltzmann distribution [

27]:

where subscripts 1 and 2 refer to an upper and a lower energy level, respectively;

is population density;

denotes the statistical weight;

is the level energy;

is the Boltzmann constant; and

is the excitation temperature to be determined. The measured intensity of a spectral line arising from the transition from level 1 to level 2 is related to the population of the upper level by:

where

is the line intensity,

is the Planck constant,

is the speed of light,

is the frequency of emission spectral lines, and

is the transition probability. Combining Equations (5) and (6) for two different spectral lines yields a practical formula for calculating the excitation temperature:

Because the working medium in this study was air, the discharge spectrum was rich in nitrogen molecular bands. Consequently, the widely used dual-line method was adopted, utilizing two prominent N

2 lines at 337.1 nm and 357.7 nm. The necessary atomic parameters for these lines are summarized in

Table 1. It should be clarified that the excitation temperature obtained in this work is a spectroscopic temperature, which characterizes the population distribution of excited atomic states rather than the actual physical temperature of the jet igniter or the bulk gas. The excitation temperature is commonly used as an effective indicator of energy exchange between electrons and heavy particles in non-equilibrium plasmas. The physical temperature of the igniter during operation is generally much lower than the excitation temperature. Therefore, the excitation temperature reported here should be interpreted as a local plasma parameter, rather than the macroscopic thermal temperature of the igniter.

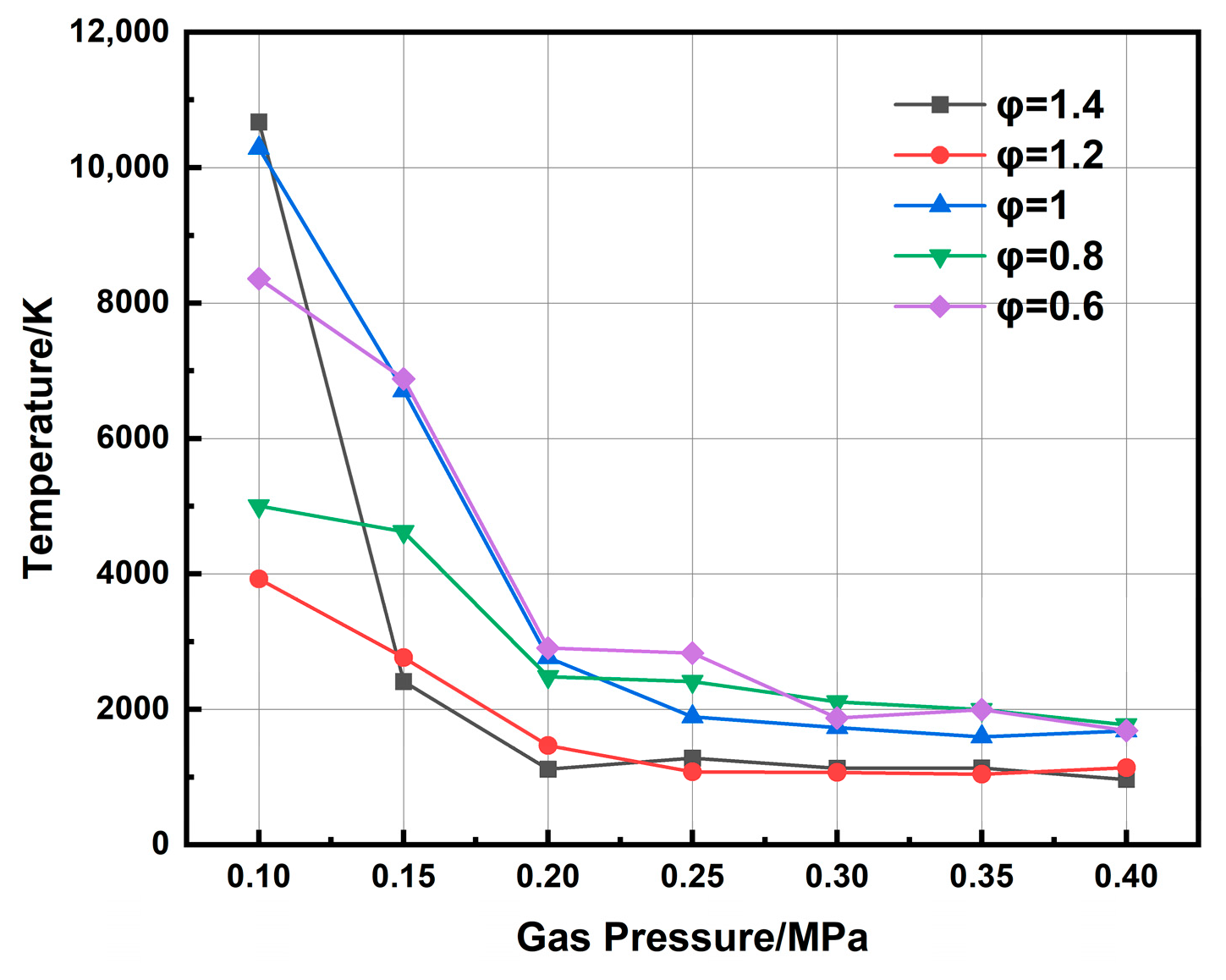

Figure 11 displays the calculated electron excitation temperature for different chamber pressures, revealing a pronounced negative correlation. A representative case at an equivalence ratio of 1 shows a decrease from 10,290 K to 1682 K as pressure rises from 0.1 MPa to 0.4 MPa. This significant reduction is attributed to a synergistic effect under elevated pressure. The increased gas density shortens the electron mean free path, limiting the energy electrons can gain from the electric field. Simultaneously, more frequent collisions with neutral species and ions promote rapid energy dissipation. Together, these mechanisms suppress the energy transfer efficiency from electrons to heavy particles, thereby lowering the overall plasma excitation temperature.

3.5. The Effect of Pressure on Exhaust Gas Composition

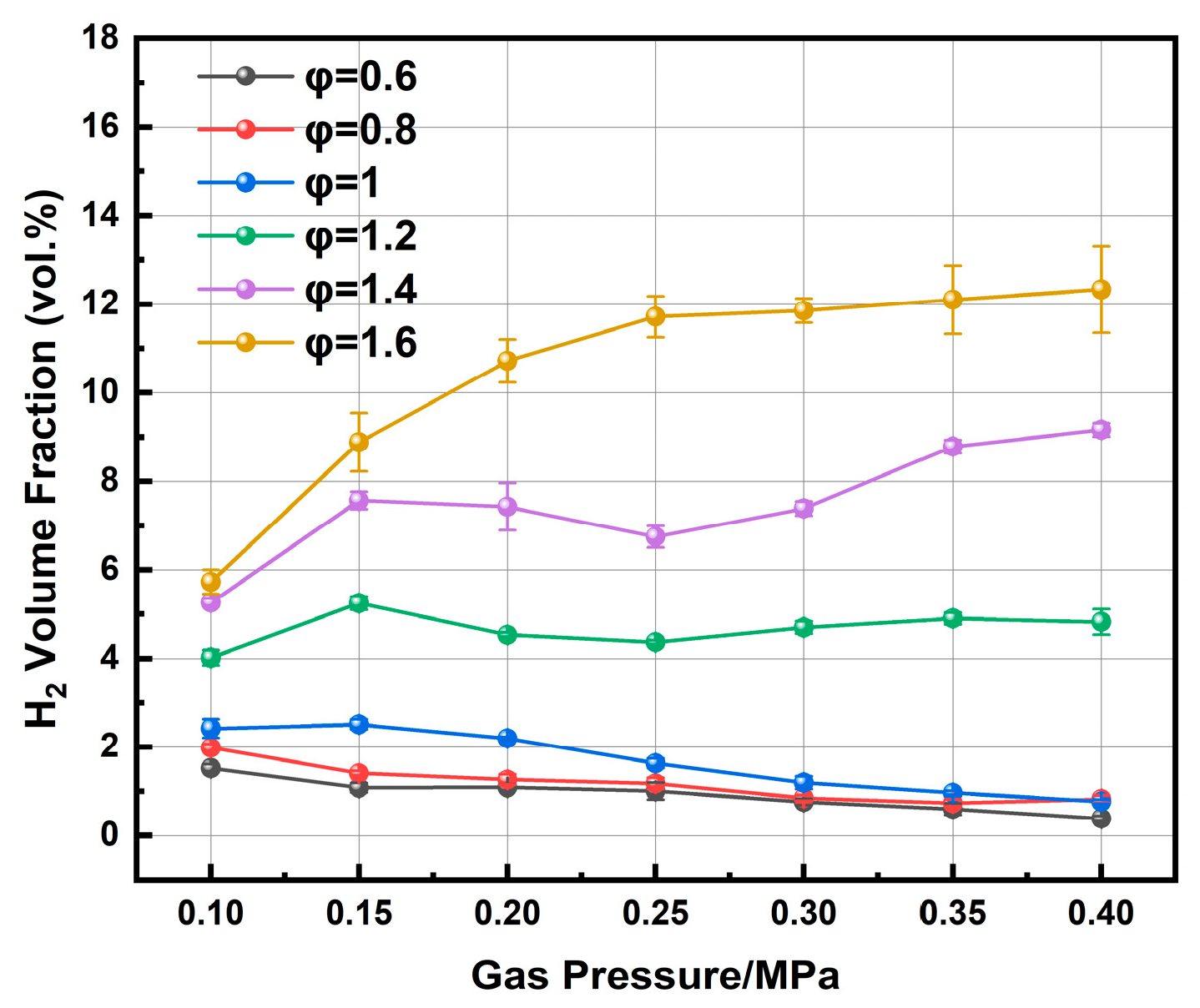

During the plasma-assisted ignition of ammonia, hydrogen is primarily generated through ammonia cracking. The analysis of hydrogen concentration in the exhaust gas reveals the influence of chamber pressure on this process. As shown in

Figure 12, hydrogen concentration exhibits different trends depending on the equivalence ratio.

As summarized in

Table 2, the hydrogen yield increases with rising pressure for φ > 1.2. For instance, at φ = 1.6, it rises from 5.73% at atmospheric pressure to 12.33% at 0.4 MPa. At φ = 1.2, the increase is more modest, from 4.02% to 4.82%. This trend can be attributed to enhanced ammonia decomposition under fuel-rich conditions, where the plasma energy is more efficiently diverted to break N-H bonds, resulting in higher H

2 yields. Furthermore, the lean-fuel environment reduces competing reactions involving oxygen, such as the oxidation of ammonia, thereby promoting the cracking pathway. Conversely, the hydrogen content slightly decreases with increasing pressure, at φ ≤ 1. This trend may stem from the higher oxygen, which promotes the oxidation of ammonia over its decomposition, consuming NH

3 that would otherwise produce H

2.

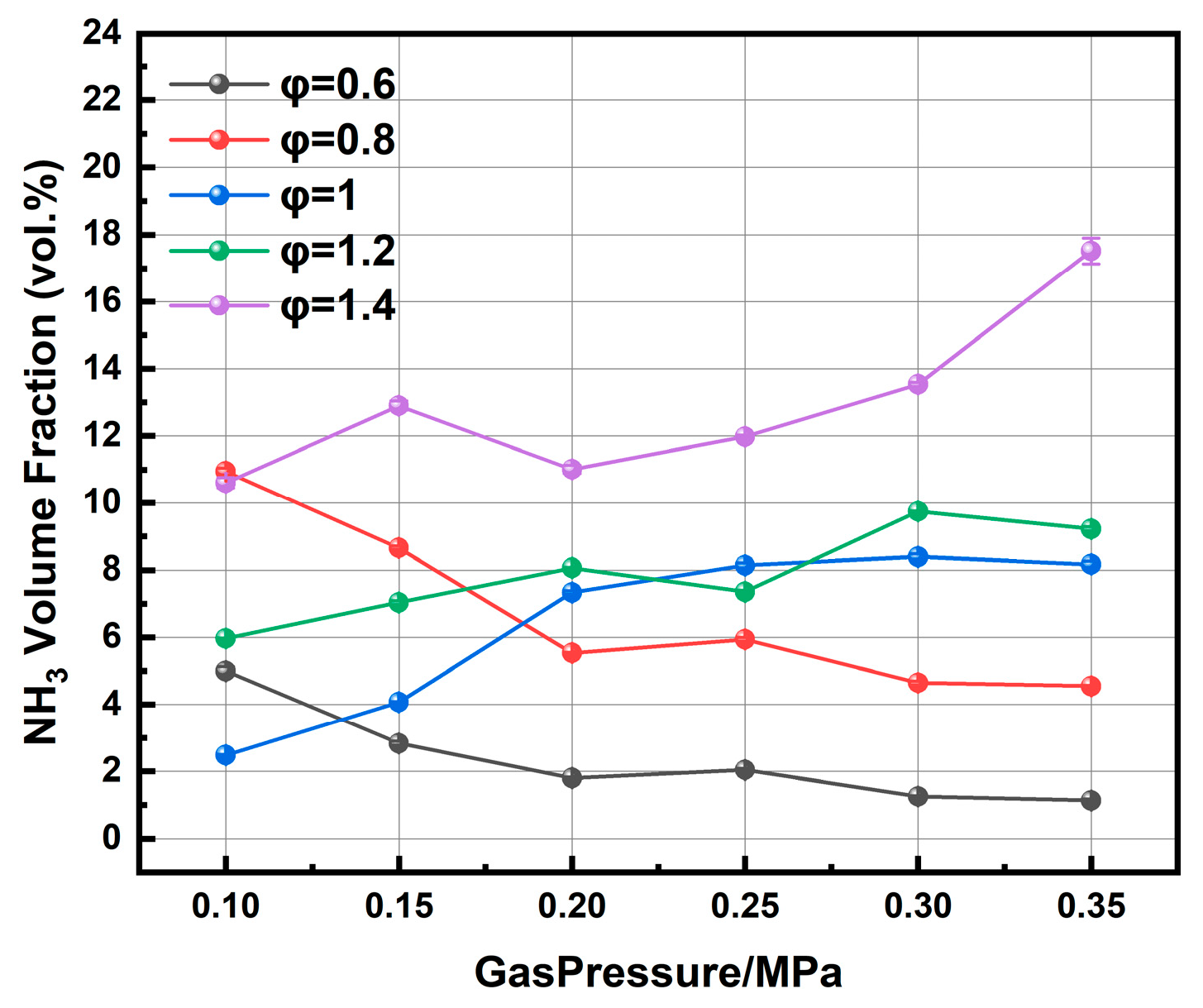

The exhaust ammonia concentration was measured at equivalence ratios from 0.6 to 1.4 under chamber pressures ranging from 0.10 to 0.35 MPa, as shown in

Figure 13. The pressure dependence of NH

3 concentration exhibits distinctly different trends depending on the equivalence ratio. Under lean conditions (φ = 0.6 and 0.8), the NH

3 concentration generally decreases with increasing pressure, although slight non-monotonic variations are observed at intermediate pressures. The NH

3 concentration shows an overall increasing trend with pressure at φ = 1.0, accompanied by local fluctuations. In contrast, the NH

3 concentration remains relatively high and increases more markedly at higher pressures under rich conditions (φ = 1.2 and 1.4).

Figure 14 shows that NO concentration decreases markedly with rising pressure at equivalence ratios between 0.6 and 1.6. The concentration of NO in the exhaust gas is closely correlated with that of NH

3. However, while NO consistently decreases with increasing pressure at different equivalence ratios, the NH

3 concentration exhibits distinct pressure-dependent trends depending on the equivalence ratio.

The reaction mechanisms involved in this study are illustrated in

Figure 15. The influence of pressure on NO formation is primarily attributed to the inhibition of O and OH radical generation under high-pressure conditions [

28,

29].

As chamber pressure increases, the gas number density increases, shortening the electron mean free path and reducing the energy gained per collision. This decreases the population of high-energy electrons responsible for generating reactive species such as O and OH. Meanwhile, the higher pressure accelerates three-body reactions (

), which enhances the consumption of OH and H radicals and further inhibits NO formation [

30,

31]. Under lean conditions (φ < 1), although oxygen is abundant, the pressure-induced inhibition of reactive oxygen species limits effective ammonia oxidation, leading to a decrease in NO concentration and a net reduction or slight variation in NH

3 with pressure. Near stoichiometric conditions (φ = 1), ammonia decomposition and oxidation pathways compete more directly. Moderate pressure enhances collision frequency and partial activation, whereas further pressure increase intensifies collisional quenching and inhibits oxidative pathways, resulting in a non-monotonic dependence of NH

3 on pressure and a continued decline in NO formation. Under rich conditions (φ > 1), oxygen availability is limited and plasma-assisted ammonia decomposition becomes dominant. Increased pressure favors stepwise NH

3 activation and stabilization of NH

x intermediates while inhibiting O- and OH-driven reactions, thereby reducing NO formation and leading to a slight decrease or even accumulation of unconverted NH

3. Overall, the observed pressure effect is governed by electron energy degradation and equivalence-ratio-dependent redistribution of reaction pathways, rather than a simple enhancement of ammonia oxidation.