Effect of the Cellular Age of the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on the Efficacy of the UV/H2O2 Oxidative Process for Water Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

2.2. Cyanobacterial Cultivation

2.3. Study Water

2.4. Experimental Procedure

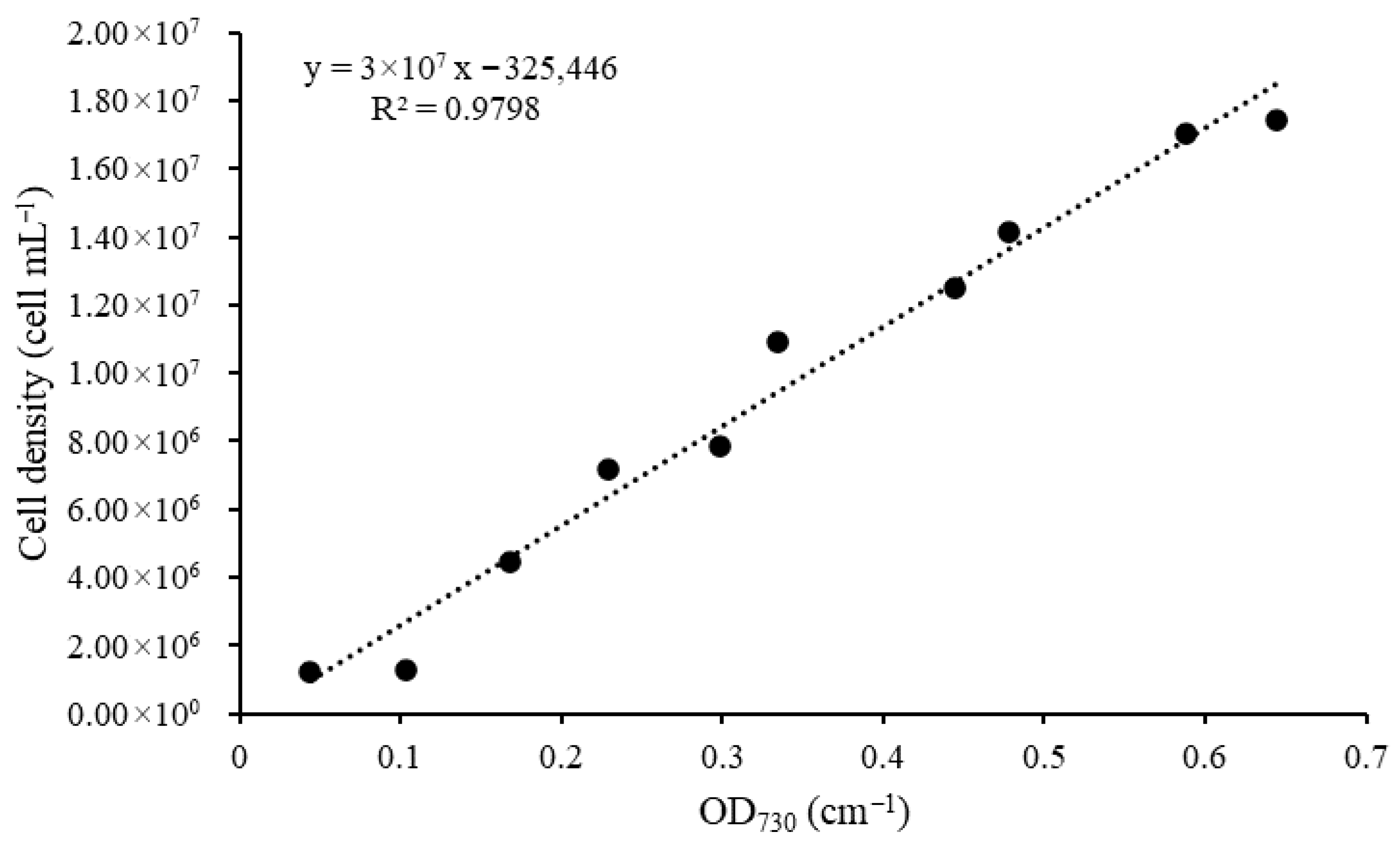

2.4.1. Evaluation of the Cell Growth of Microcystis aeruginosa

2.4.2. Photo-Oxidative Assays

2.5. Analytical Methods

2.5.1. Cell Counting

2.5.2. Determination of H2O2 Concentration

2.5.3. Determination of Optical Density

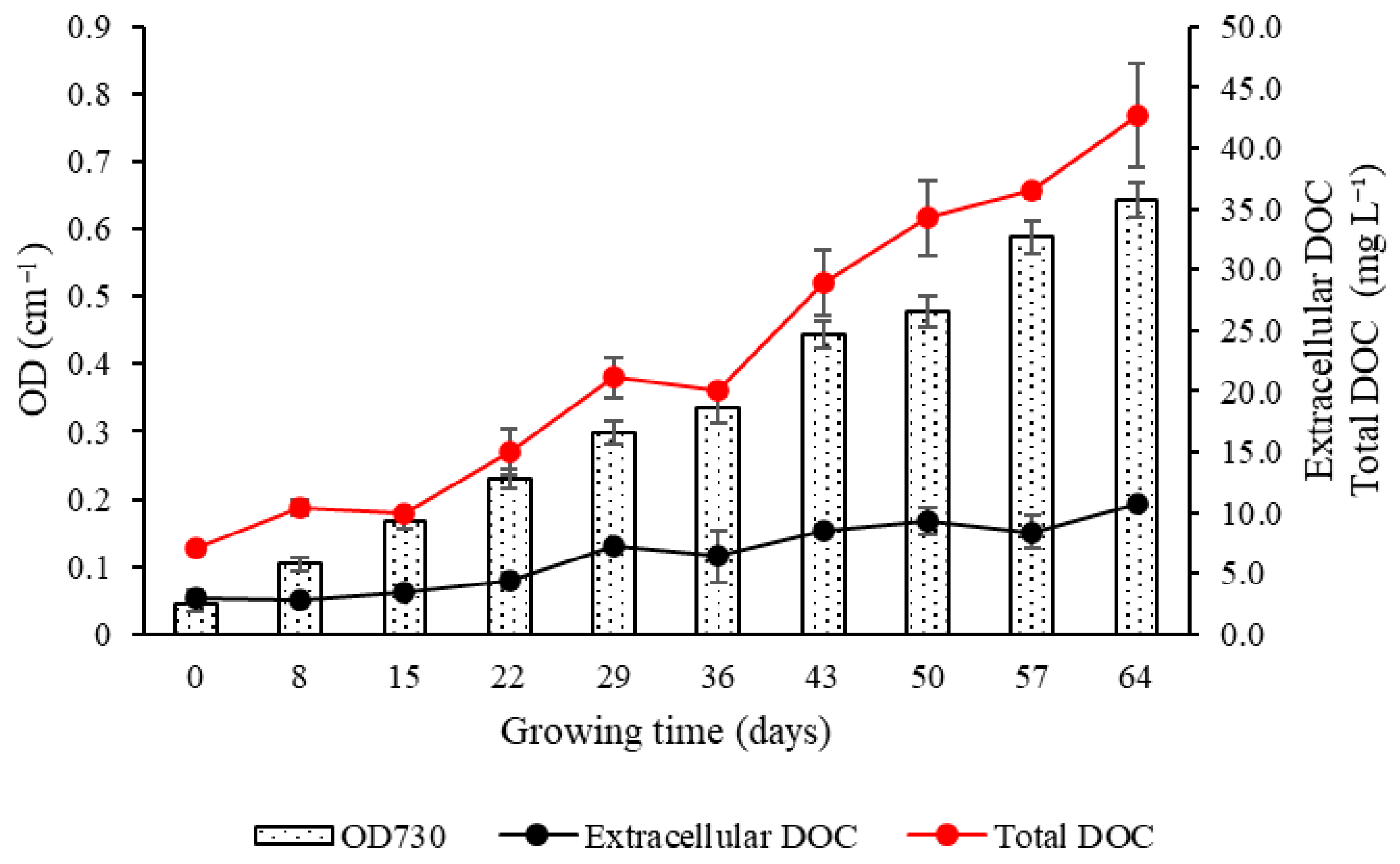

2.5.4. Determination of Extracellular and Total Dissolved Organic Carbon

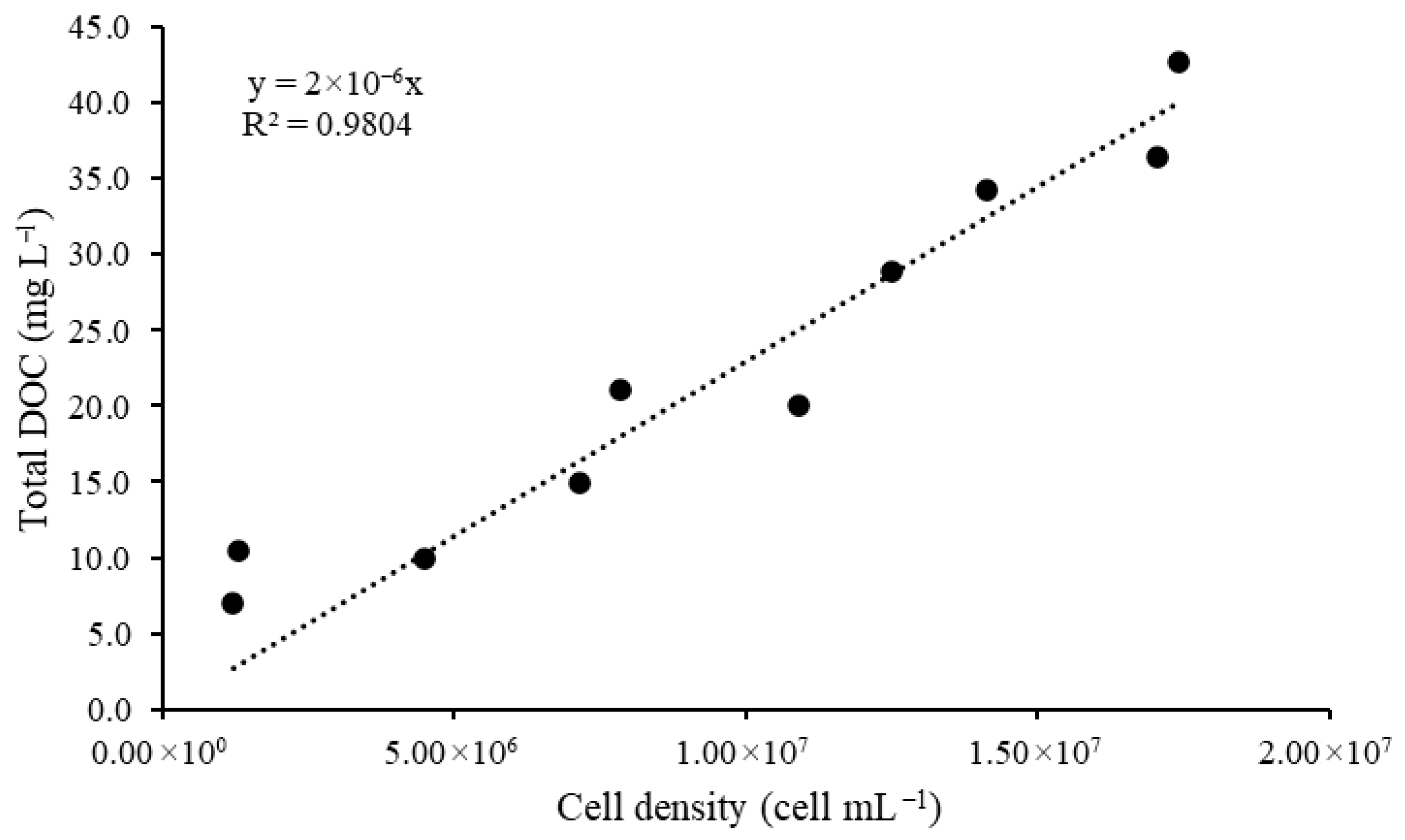

2.5.5. Determination of the Extracellular DOC Fraction in Total DOC

3. Results and Discussion

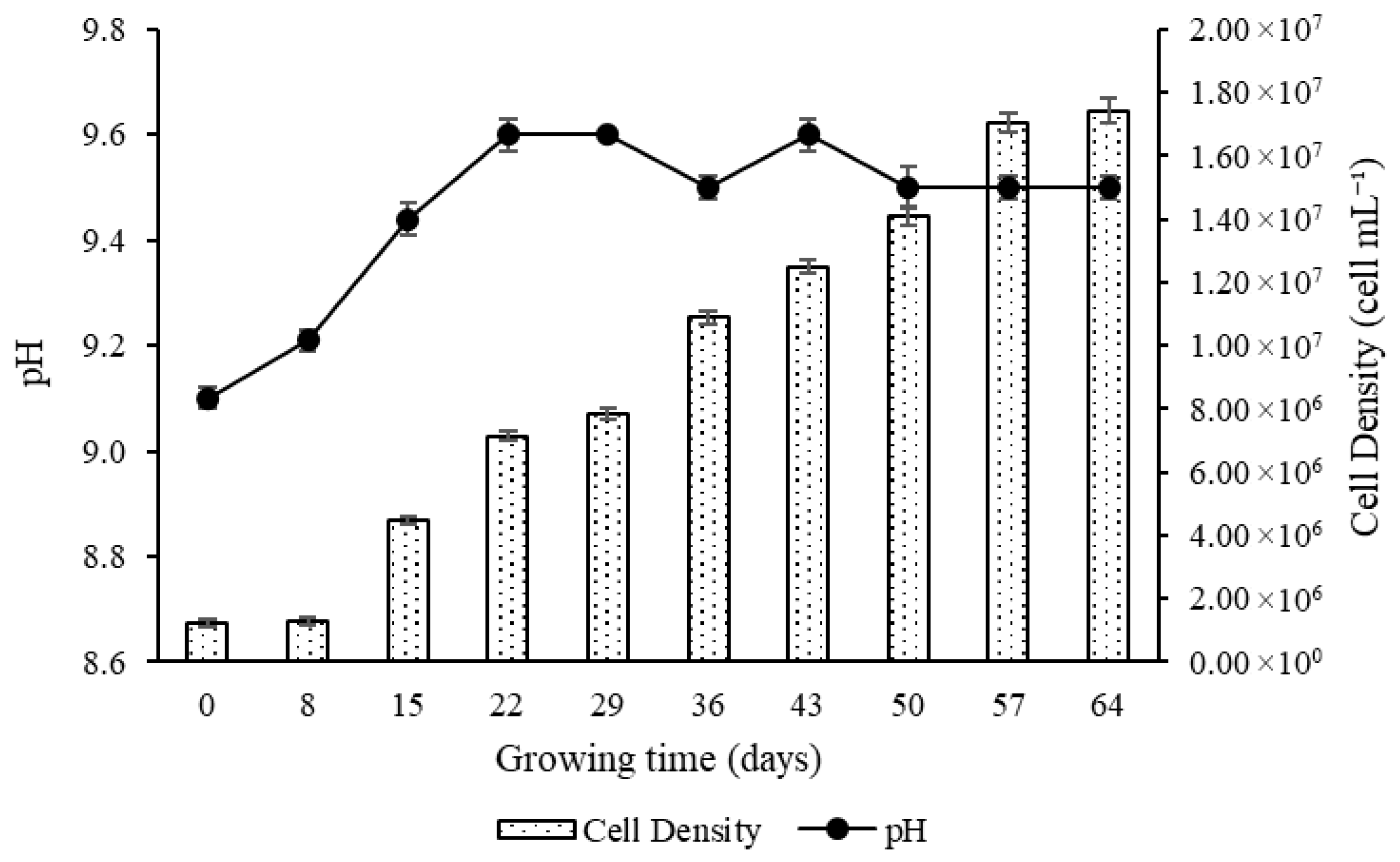

3.1. Growth Curve of Microcystis aeruginosa

3.2. Photo-Oxidative Experiments

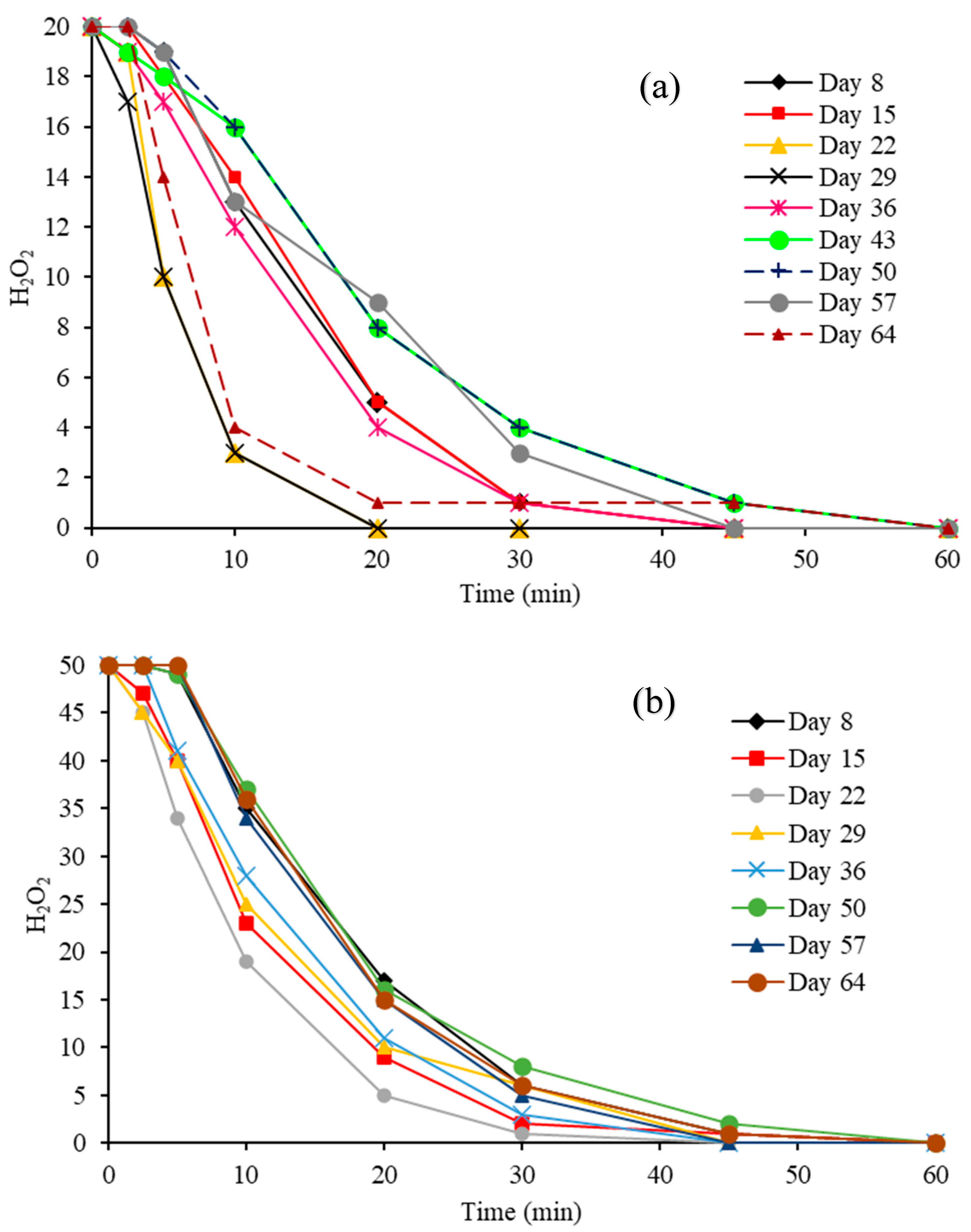

3.2.1. Residual H2O2

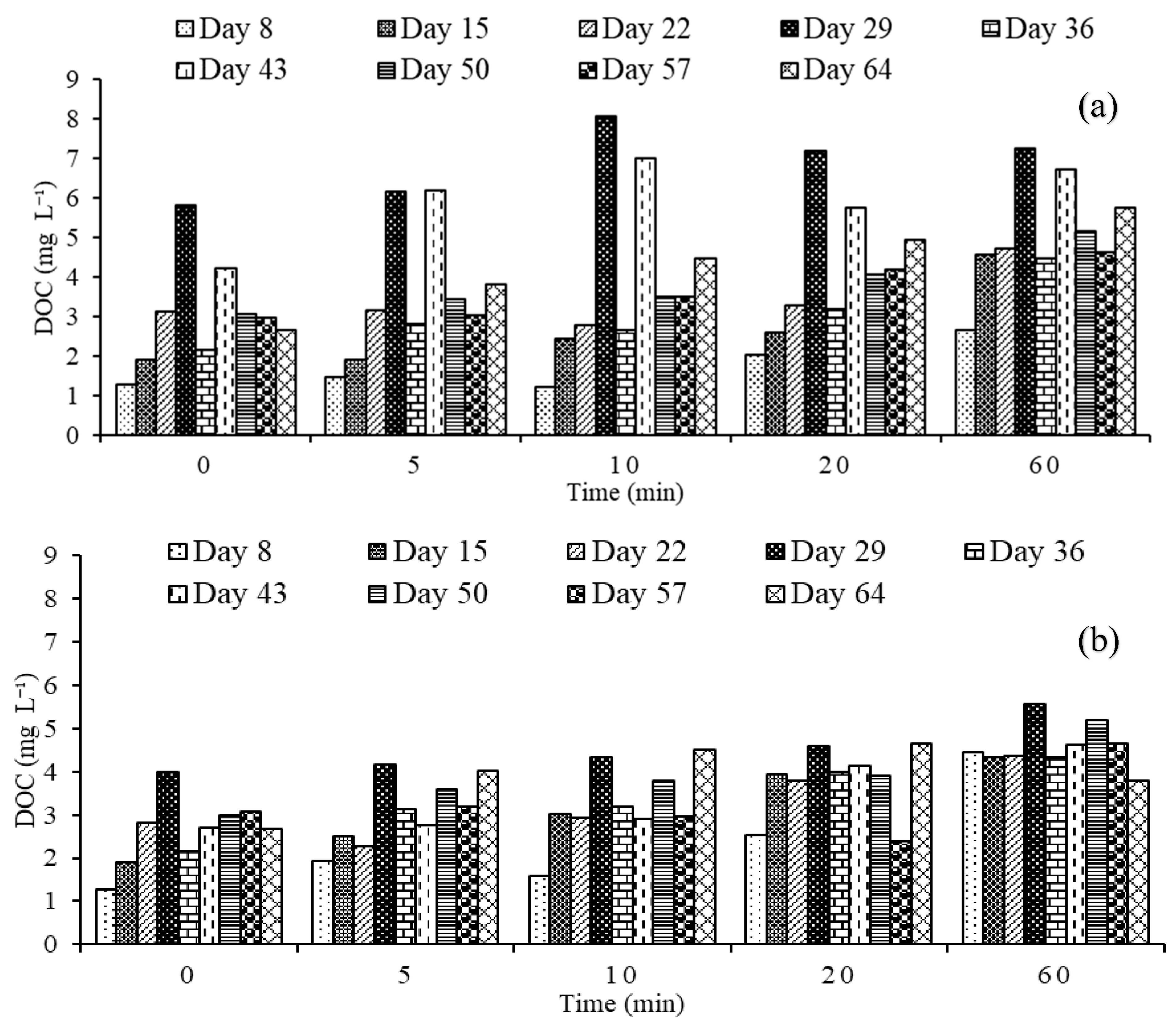

3.2.2. Dissolved Organic Carbon

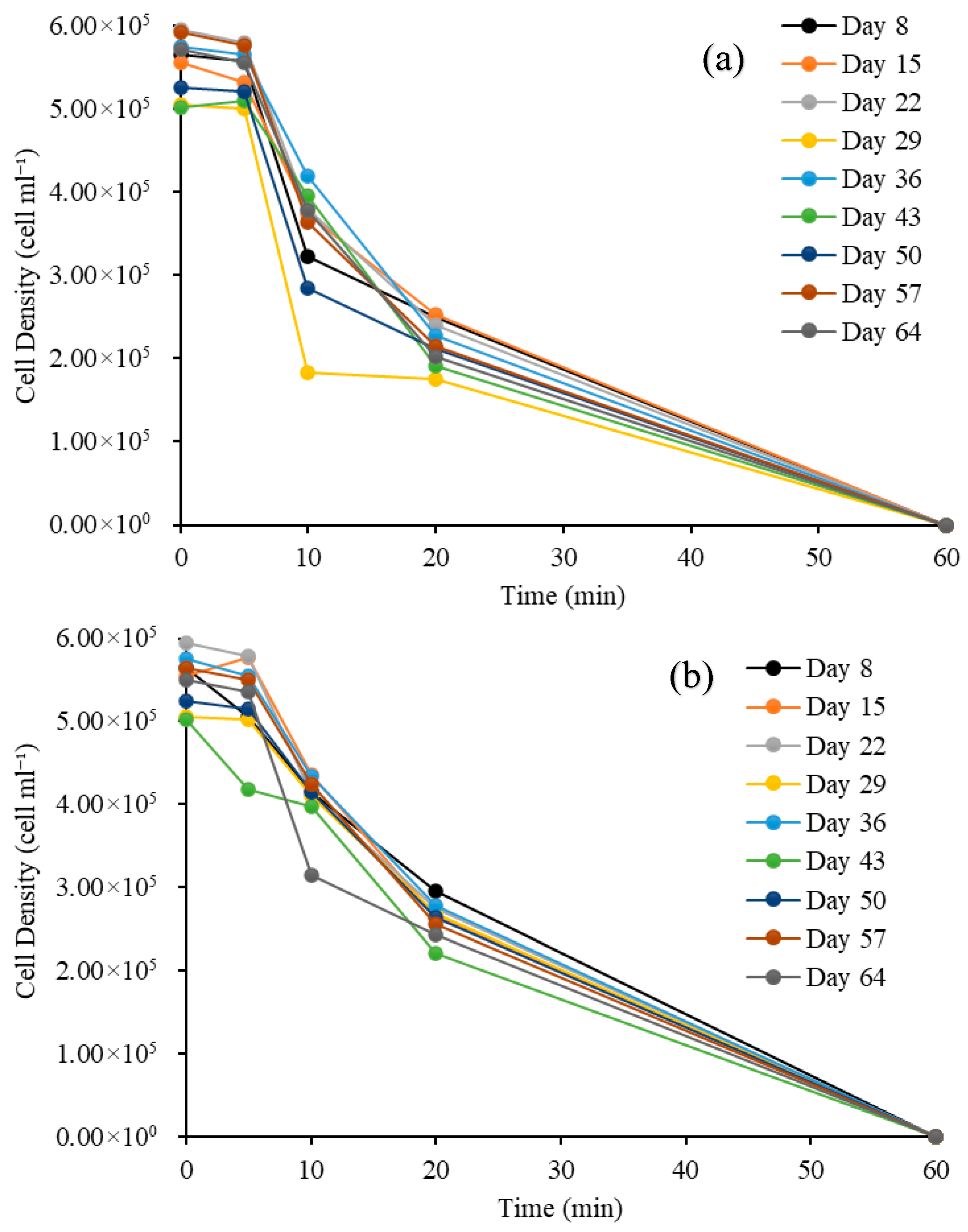

3.2.3. Cell Density

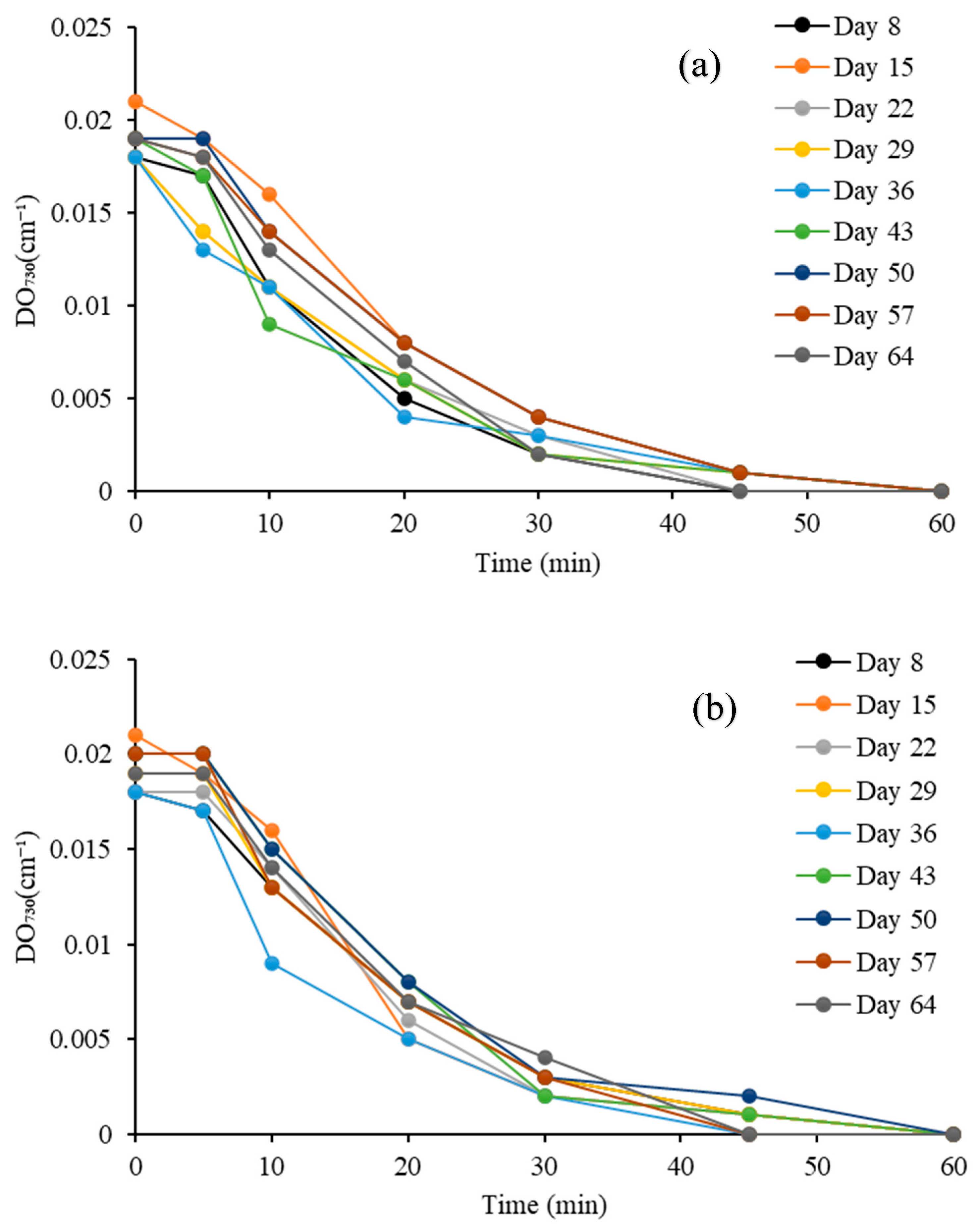

3.2.4. Optical Density

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madjar, R.M.; Scăețeanu, G.V.; Sandu, M.A. Nutrient Water Pollution from Unsustainable Patterns of Agricultural Systems, Effects and Measures of Integrated Farming. Water 2024, 16, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Blas, F.M.; Ramos-Saravia, J.C.; Cossío-Rodríguez, P.L. Removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Municipal Wastewater Through Cultivation of Microalgae Chlorella sp. in Consortium. Water 2025, 17, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, R.; Azevedo, S. Ecofisiologia de cianobactérias produtoras de cianotoxinas. Oecol. Bras. 2009, 13, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradíssimo, D.G.; Mourão, M.M.; Santos, A.V. Importância do Monitoramento de Cianobactérias e Suas Toxinas em Águas Para Consumo Humano. J. Crim. 2020, 9, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceição Albuquerque, M.V.; Cartaxo, A.S.B.; Silva, M.C.C.P.; Ramos, R.O.; Sátiro, J.R.; Lopes, W.S.; Leite, V.D.; Ceballos, B.S.O. Removal of cyanbacteria and cyanotoxins present in waters from eutrophized reservoir by advanced oxidative process (AOPs). Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 61234–61248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, D.; Dantas, A.D.B. Métodos e Técnicas de Tratamento de Água; Rima Editora: São Carlos, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.N.C.E.; de Oliveira, R.; Ceballos, B.S.O.; Guerra, A.B.; de Aquino, S.F.; Libânio, M. Hierarquização da eficiência de remoção de cianotoxinas por meio de adsorção em carvão ativado granular. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2017, 22, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, F.; Moradinejad, S.; Zamyadi, A.; Dorner, S.; Sauvé, S.; Prévost, M. Evidence-based framework to manage cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in water and sludge from drinking water treatment plants. Toxins 2022, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, R.M.B.; Paludo, L.C.; Monteiro, P.I.; Rocha, L.V.M.; Moraes, C.V.; Santos, O.O.; Alves, E.R.; Dantas, T.L.P. Amoxicillin degradation by iron photonanocatalyst synthetized by green route using pumpkin (Tetsukabuto) peel extract. Talanta 2023, 260, 124658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, R.M.B.; Monteiro, P.I.; da Rocha, L.V.M.; Santos, O.O.; Alves, E.R.; Dantas, T.L.P. Experimental Investigation of Antibiotic Photodegradation Using a Nanocatalyst Synthesized via an Eco-Friendly Process. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Li, T. UV/H2O2 process under high intensity UV irradiation: A rapid and effective method for methylene blue decolorization. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.F.P.; Jardim, W.F. Heterogeneous photocatalysis and its environmental applications. Quim. Nova 1998, 21, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Shin, J.; Yoon, S.; Jang, T.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.-K.; Park, J.-A. Bacteria and Cyanobacteria Inactivation Using UV-C, UV-C/H2O2, and Solar/H2O2 Processes: A Comparative Study. Water 2024, 16, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral, L.A.; Zamyadi, A.; Barbeau, B.; Bassetti, F.J.; Lapolli, F.R.; Prevost, M. Oxidation of Microcystis aeruginosa and Anabaena flos-aquae by ozone: Impacts on cell integrity and chlorination by-product formation. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.F.P.; Oliveira, M.C.; Paterlini, W.C. Simple and fast spectrophotometric determination of H2O2 in photo-Fenton reactions using metavanadate. Talanta 2005, 66, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Graham, N.; Templeton, M.R.; Zhang, Y.; Collins, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. A comparison of the role of two blue–green algae in THM and HAA formation. Water Res. 2009, 43, 3009–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.K.; Sundaram, S.; Patel, A.K.; Kalra, A. Characterization of seven species of cyanobacteria for high-quality biomass production. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.T. Potential of Ionizing Radiation to Reduce the Toxicity of Cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa. Master’s Thesis, Mestrado em Tecnologia Nuclear—Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares, IPEN-CNEN/SP, São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mattos, I.L.; Shiraishi, K.A.; Braz, A.D.; Fernandes, J.R. Hydrogen peroxide: Importance and determination. Quim. Nova 2003, 26, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, K.C.D.; Neto, J.C. Use of hydrogen peroxide in the control of cyanobacteria—A biochemical perspective. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2022, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioreze, M.; Santos, E.P.; Schmachtenberg, N. Advanced oxidative processes: Fundamentals and environmental application. Electron. J. Manag. Educ. Environ. Technol. 2014, 18, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buley, R.P.; Gladfelter, M.F.; Fernandez-Figueroa, E.G.; Wilson, A.E. Complex effects of dissolved organic matter, temperature, and initial bloom density on the efficacy of hydrogen peroxide to control cyanobacteria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43991–44005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, G.A. Avaliação do Potencial de Formação de Carbono Orgânico Assimilável a Partir da Exposição de Células de Cianobactérias ao Processo UV/H2O2; Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná: Curitiba, Brazil, 2021; Available online: http://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/28282 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Piel, T.; Sandrini, G.; White, E.; Xu, T.; Schuurmans, J.M.; Huisman, J.; Visser, P.M. Suppressing cyanobacteria with hydrogen peroxide is more effective at high light intensities. Toxins 2019, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siquerolo, L.V.; Ramos, R.M.B.; Monteiro, P.I.; Silveira, G.F.; Bassetti, F.d.J.; Coral, L.A.d.A. Impact of the UV/H2O2 Process on Assimilable Organic Carbon and Trihalomethane Formation in Cyanobacteria-Contaminated Waters. Processes 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Chang, M.; Bi, Y.; Hu, Z. The combined effects of UV-C radiation and H2O2 on Microcystis aeruginosa, a bloom-forming cyanobacterium. Chemosphere 2015, 141, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, G.; Zhan, J.; Luo, J.; Lin, J.; Qu, F.; Du, B.; You, Y.; Yan, Z. Fabrication of heterostructured Ag/AgCl@ g-C3N4@ UIO-66 (NH2) nanocomposite for efficient photocatalytic inactivation of Microcystis aeruginosa under visible light. J. Hazard Mater. 2021, 404, 124062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Growth Time (Days) | Total DOC (mg L−1) | Cell Density (Cell mL−1) | The DOC/Cell Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | ±10.4 | 1.29 × 106 | 2.33 × 10−6 |

| 15 | ±10.0 | 4.48 × 106 | 2.23 × 10−6 |

| 22 | ±15.0 | 7.15 × 106 | 2.10 × 10−6 |

| 29 | ±19.9 | 7.85 × 106 | 2.53 × 10−6 |

| 36 | ±20.1 | 10.9 × 106 | 1.84 × 10−6 |

| 43 | ±26.9 | 12.5 × 106 | 2.15 × 10−6 |

| 50 | ±32.1 | 14.1 × 106 | 2.27 × 10−6 |

| 57 | ±35.7 | 17.1 × 106 | 2.09 × 10−6 |

| 64 | ±35.8 | 17.4 × 106 | 2.22 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lückmann, B.; Ramos, R.M.B.; Monteiro, P.I.; Coral, L.A.d.A. Effect of the Cellular Age of the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on the Efficacy of the UV/H2O2 Oxidative Process for Water Treatment. Processes 2026, 14, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020361

Lückmann B, Ramos RMB, Monteiro PI, Coral LAdA. Effect of the Cellular Age of the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on the Efficacy of the UV/H2O2 Oxidative Process for Water Treatment. Processes. 2026; 14(2):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020361

Chicago/Turabian StyleLückmann, Beatriz, Rúbia Martins Bernardes Ramos, Pablo Inocêncio Monteiro, and Lucila Adriani de Almeida Coral. 2026. "Effect of the Cellular Age of the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on the Efficacy of the UV/H2O2 Oxidative Process for Water Treatment" Processes 14, no. 2: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020361

APA StyleLückmann, B., Ramos, R. M. B., Monteiro, P. I., & Coral, L. A. d. A. (2026). Effect of the Cellular Age of the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on the Efficacy of the UV/H2O2 Oxidative Process for Water Treatment. Processes, 14(2), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020361