A Sustainable Aluminium-Based Electro-Fenton Process for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment: Optimization, Kinetics, and Cost–Benefit Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

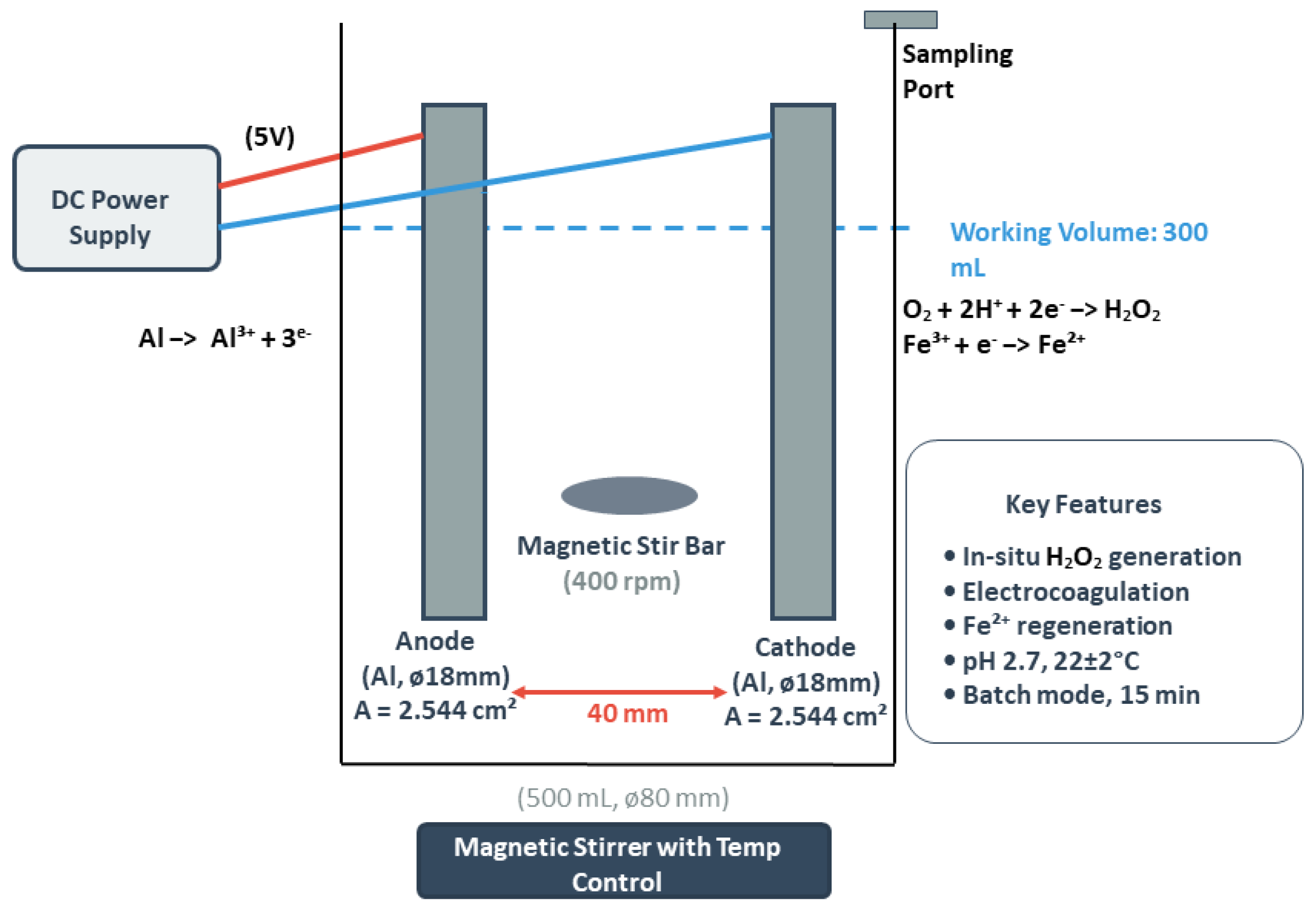

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Aluminum Electrode Characteristics

3. Results and Discussion

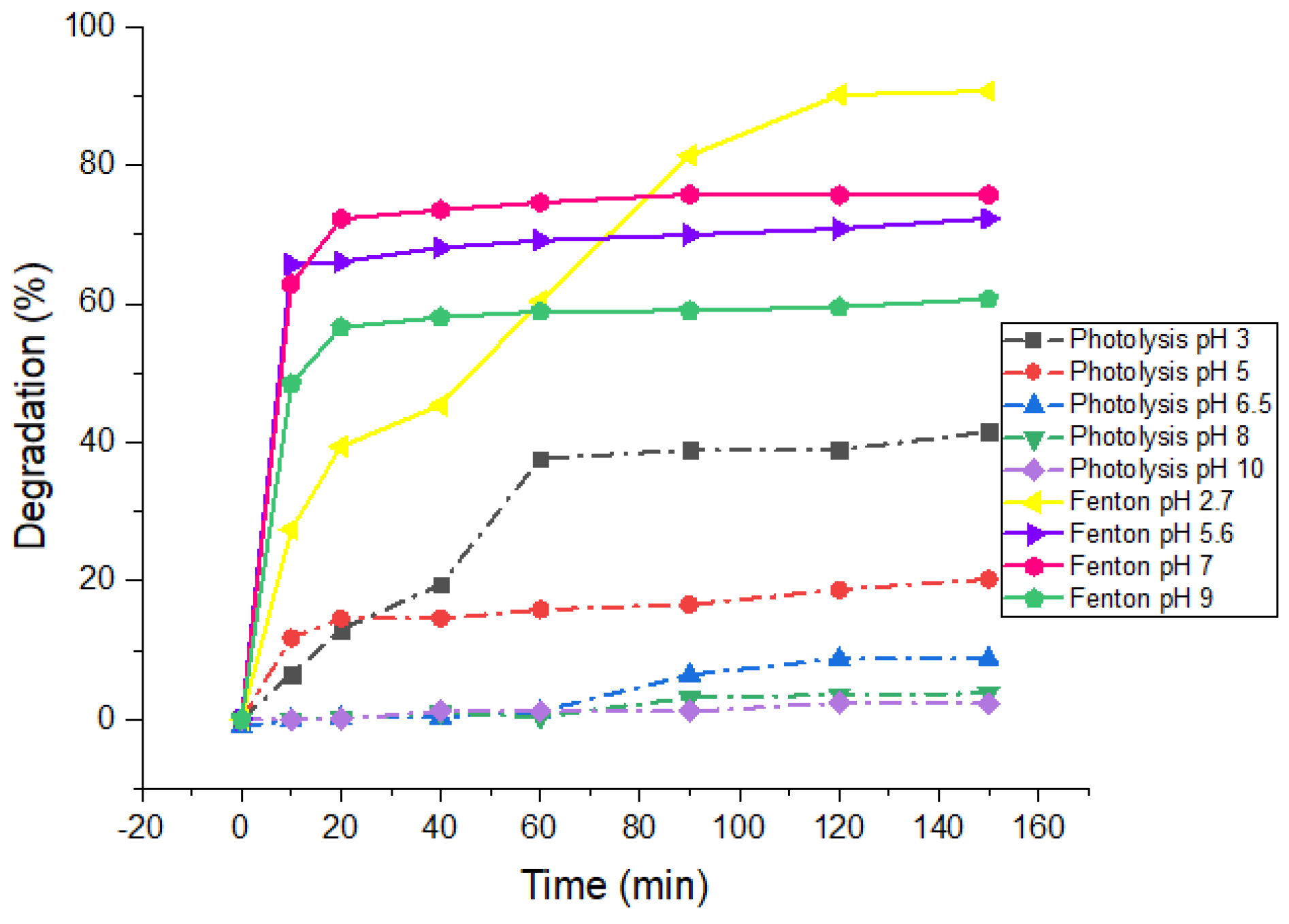

3.1. pH Effect

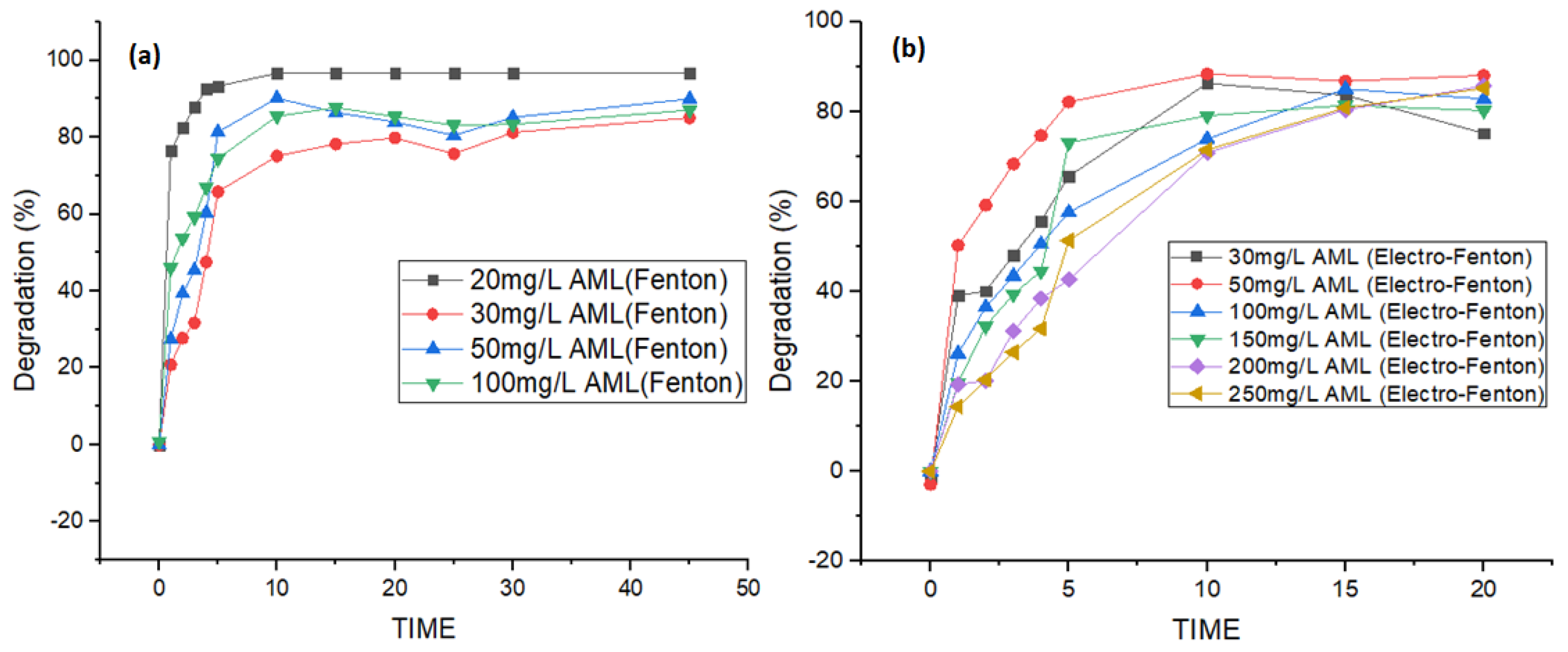

3.2. Effect of Initial Concentration of Amlodipine (AML)

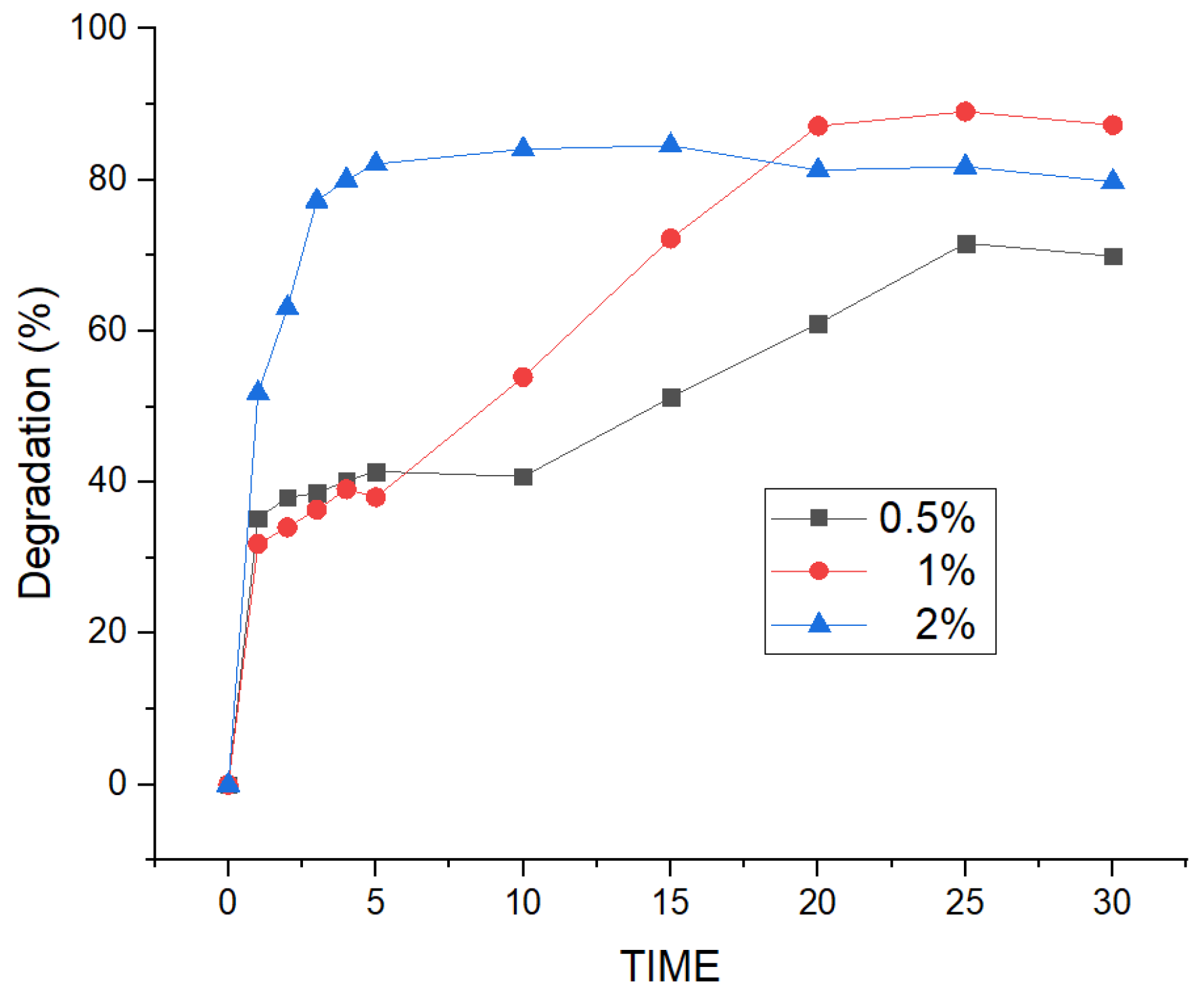

3.3. Effect of the Concentration of FeCl3

3.4. Effect of H2O2 Concentration on AML Removal

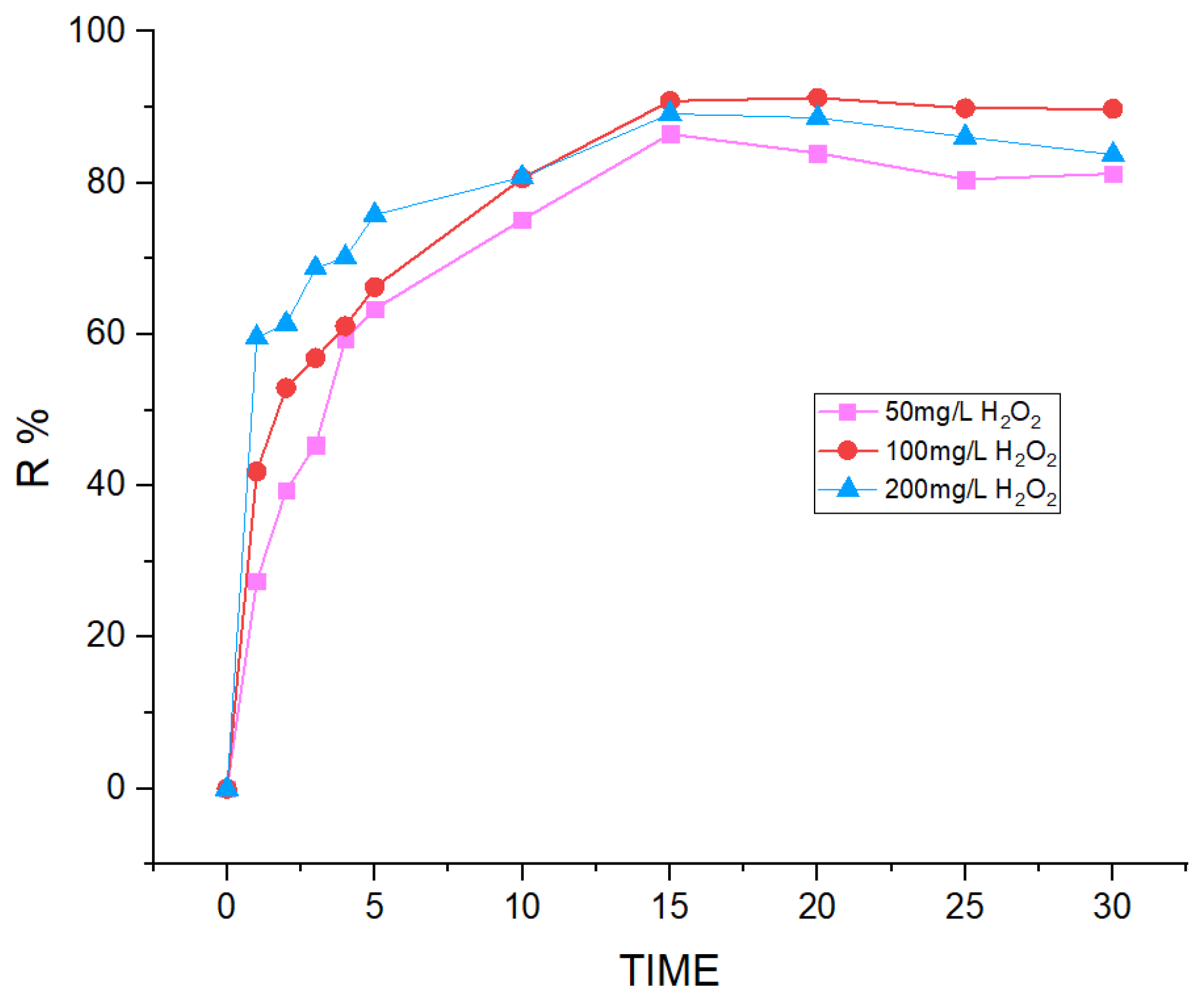

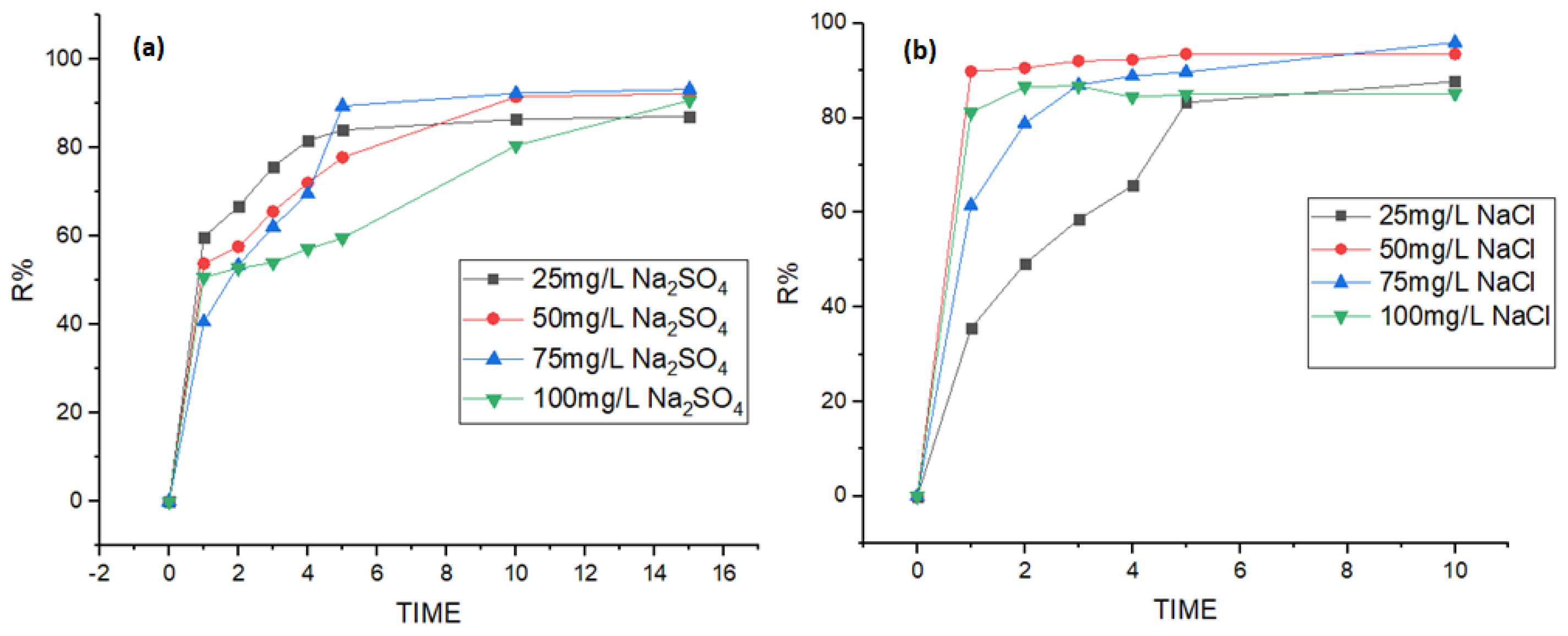

3.5. Effect of Electrolyte Type and Concentration

3.6. Degradation Kinetics

3.7. Electrode Stability and Reusability

3.8. Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency Assessment

3.9. Degradation Pathway and Toxicity Considerations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brillas, E. A review on the photoelectro-Fenton process as efficient electrochemical advanced oxidation for wastewater remediation. Treatment with UV light, sunlight, and coupling with conventional and other photo-assisted advanced technologies. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.C.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Brillas, E.; Vilar, V.J.P. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: A review on their application to synthetic and real wastewaters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 217–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Sirés, I. Electrochemical removal of pharmaceuticals from water streams: Reactivity elucidation by mass spectrometry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 70, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.R.; Venkatesan, P.; Kanimozhi, R.; Basha, C.A. Removal of pharmaceuticals from wastewater by electrochemical oxidation using cylindrical flow reactor and optimization of treatment conditions. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2009, 44, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporsho, S.S.; Saha, D.; Khan, M.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Rukh, M.; Islam, M.R.; Chakma, T.; Haque, F.; Roy, H.; Sarkar, D.; et al. Insights into adsorbent-based pharmaceutical wastewater treatment and future developments toward sustainability. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 50597–50632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, V.; Acevedo, S.; Marco, P.; Giménez, J.; Esplugas, S. Enhancement of Fenton and photo-Fenton processes at initial circumneutral pH for the degradation of the β-blocker metoprolol. Water Res. 2016, 88, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboula, V.M. Devenir de Polluants Émergents lors d’un Traitement Photochimique ou Photocatylitique sous Irradiation Solaire. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole des Mines de Nantes, Nantes, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ouda, M.; Kadadou, D.; Swaidan, B.; Al-Othman, A.; Al-Asheh, S.; Banat, F.; Hasan, S.W. Emerging contaminants in the water bodies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, H.; Shao, S.; Lu, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Gao, S. Montmorillonite promoted photodegradation of amlodipine in natural water via formation of surface complexes. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.V.; Karad, M.M.; Deshpande, P.B. Development and Validation of Stability-Indicating Rp Hplc Method for Determination of Indapamide and Amlodipine Besylate. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2014, 48, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadra, J.; Molina-Prados, S.; Mínguez-Vega, G.; Abderrahim, L.; Colombari, J.; Carda, J.; Gonçalves, N.P.; Novais, R.; Labrincha, J. Generation of Schottky heterojunction (SnO2-Au NPs) transparent thin film for ciprofloxacin photodegradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2025, 27, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturan, M.A. Outstanding performances of the BDD film anode in electro-Fenton process: Applications and comparative performance. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2021, 25, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán-Trinidad, M.; Guadarrama-Pérez, O.; Guillén-Garcés, R.A.; Bustos-Terrones, V.; Trevino-Quintanilla, L.G.; Moeller-Chávez, G. The Grey–Taguchi Method, a Statistical Tool to Optimize the Photo-Fenton Process: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, F.; Belver, C.; Liu, W.; Shang, Y.; Luo, S.; Wei, Z. Surface and morphology modulated adsorption-activation of trace concentration hydrogen peroxide with multiple electron transfer pathways and sustained Fenton reactions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 364, 124840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, I.E.B.; Ilhan, F.; Kurt, U.; Yetilmezsoy, K. An Optimization Study of Advanced Fenton Oxidation Methods (UV/Fenton–MW/Fenton) for Treatment of Real Epoxy Paint Wastewater. Water 2024, 16, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhou, Z. Electro-Fenton process for water and wastewater treatment. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 47, 2100–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Huang, C.P.; Hu, C.C.; Huang, C. A dual TiO2/Ti-stainless steel anode for the degradation of orange G in a coupling photoelectrochemical and photo-electro-Fenton system. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhou, M.; Ren, G.; Yang, W.; Liang, L. A highly energy-efficient flow-through electro-Fenton process for organic pollutants degradation. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 200, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.P.; Saravanakumar, M. A Review on Electrooxidation Treatment of Leachate: Strategies, New Developments, and Prospective Growth. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2025, 24, B4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaviska, F.; Drogui, P.; Mercier, G.; Blais, J.F. Procédés d’oxydation avancée dans le traitement des eaux et des effluents industriels: Application à la dégradation des polluants réfractaires. Rev. Sci. l’Eau 2009, 22, 535–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirés, I.; Brillas, E.; Oturan, M.A.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: Today and tomorrow. A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8336–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirés, I.; Brillas, E. Remediation of water pollution caused by pharmaceutical residues based on electrochemical separation and degradation technologies: A review. Environ. Int. 2012, 40, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, J.C.; Da Boit Martinello, K.; Da Silveira, C.L.; Pereira, H.A.; Franco, D.S.P.; Silva, L.F.O.; Dotto, G.L. New insights into glyphosate adsorption on modified carbon nanotubes via green synthesis: Statistical physical modeling and steric and energetic interpretations. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber-Jarlachowicz, P.; Gworek, B.; Kalinowski, R. Removal efficiency of pharmaceuticals during the wastewater treatment process: Emission and environmental risk assessment. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridruejo, C.; Alcaide, F.; Álvarez, G.; Brillas, E.; Sirés, I. On-site H2O2 electrogeneration at a CoS2-based air-diffusion cathode for the electrochemical degradation of organic pollutants. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 808, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Garcia-Segura, S. Benchmarking recent advances and innovative technology approaches of Fenton, photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, and related processes: A review on the relevance of phenol as model molecule. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 237, 116337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kushwaha, J.P.; Singh, N. Amoxicillin electro-catalytic oxidation using Ti/RuO2 anode: Mechanism, oxidation products and degradation pathway. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 296, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.; Nazari, S. Applying Response Surface Methodology to Optimize the Fenton Oxidation Process in the Removal of Reactive Red 2. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, B.M.; Zyadah, M.A.; Ali, M.Y.; El-Sonbati, M.A. Pre-treatment of composite industrial wastewater by Fenton and electro-Fenton oxidation processes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebi, B.; Ayati, B. Degradation of Emerging Amoxicillin Compound from Water Using the Electro-Fenton Process with an Aluminum Anode. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Qian, L.; Zhan, X.; Wang, M.; Lu, K.; Peng, J.; Miao, D.; Gao, S. Transformation and toxicity evolution of amlodipine mediated by cobalt ferrite activated peroxymonosulfate: Effect of oxidant concentration. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 123005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturan, M.A.; Aaron, J.J. Advanced Oxidation Processes in Water/Wastewater Treatment: Principles and Applications. A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 2577–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.S.; Bahena, C.L. Chlorbromuron urea herbicide removal by electro-Fenton reaction in aqueous effluents. Water Res. 2009, 43, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Gandhimathi, R. Trends in electro-Fenton process for water and wastewater treatment: An overview. Desalination 2012, 299, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuan, R.; Wang, J. Enhanced degradation and mineralization of sulfamethoxazole by integrating gamma radiation with Fenton-like processes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 166, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Espinoza, J.D.; Mijaylova-Nacheva, P.; Avilés-Flores, M. Electrochemical carbamazepine degradation: Effect of the generated active chlorine, transformation pathways and toxicity. Chemosphere 2018, 192, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Zhou, M.; Oturan, M.A. An overview on the removal of synthetic dyes from water by electrochemical advanced oxidation processes. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, P. A review on Fenton-like processes for organic wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 762–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wei, W.; Wu, H.; Gong, H.; Zhou, K.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, S.; Gui, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, S. Coupling Electro-Fenton and Electrocoagulation of Aluminum–Air Batteries for Enhanced Tetracycline Degradation: Improving Hydrogen Peroxide and Power Generation. Molecules 2024, 29, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Garcia-Segura, S. Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes for Real Wastewater Remediation: Systems, Performance, and Generated Oxidants. ACS Electrochem. 2025, 1, 2292–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.O.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Oturan, M.A. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: Advances in formation and detection of reactive species and mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 27, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liang, J.; Ji, F.; Dong, H.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Q. Accelerated degradation of pharmaceuticals by ferrous ion/chlorine process: Roles of Fe (IV) and reactive chlorine species. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dong, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Meng, D. A review on Fenton process for organic wastewater treatment based on optimization perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.T.; Chou, W.L.; Chung, M.H.; Kuo, Y.M. COD removal from real dyeing wastewater by electro-Fenton technology using an activated carbon fiber cathode. Desalination 2010, 253, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, E.; Da Pozzo, A.; Di Palma, L. On the ability to electrogenerate hydrogen peroxide and to regenerate ferrous ions of three selected carbon-based cathodes for electro-Fenton processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Rajic, L.; Chen, L.; Kou, K.; Ding, Y.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Mulaw, B.; Gao, J.; Qin, Y.; et al. Activated carbon as effective cathode material in iron-free Electro-Fenton process: Integrated H2O2 electrogeneration, activation, and pollutants adsorption. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 296, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Teng, W.; Fan, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.x. Enhanced degradation of micropollutants over iron-based electro-Fenton catalyst: Cobalt as an electron modulator in mesochannels and mechanism insight. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, B.; Tang, Y.; Li, T.; Yu, H.; Cui, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Su, P.; Zhang, R. Technological Advancements and Prospects for Near-Zero-Discharge Treatment of Semi-Coking Wastewater. Water 2024, 16, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, L.S.; Zhou, L.J.; Fan, J.P.; Wu, D.S.; Zou, J.P. New insights on the role of NaCl electrolyte for degradation of organic pollutants in the system of electrocatalysis coupled with advanced oxidation processes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Liu, M.; Yang, T.; Chen, M.; Qian, L.; Mao, S.; Cai, J.; Zhao, H. Controllable generation of sulfate and hydroxyl radicals to efficiently degrade perfluorooctanoic acid in cathode-dominated electrochemical process. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3, 3696–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Vione, D.; Rivoira, L.; Carena, L.; Castiglioni, M.; Bruzzoniti, M.C. A review on the degradation of pollutants by fenton-like systems based on zero-valent iron and persulfate: Effects of reduction potentials, pH, and anions occurring in waste waters. Molecules 2021, 26, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Electro-Fenton degradation of synthetic dyes. Water Res. 2009, 43, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Sirés, I.; Oturan, M.A. Electro-Fenton process and related electrochemical technologies based on Fenton’s reaction chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6570–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.; Alalm, M.G.; El-Etriby, H.K. Application of electro-Fenton process for treatment of water contaminated with benzene, toluene, and p-xylene (BTX) using affordable electrodes. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M.A. Valorization of undervalued aluminum-based waterworks sludge waste for the science of “The 5 Rs’ criteria”. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods. An updated review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Dong, Z.; Chen, R.; Wu, Q.; Li, J. Review of carbon-based nanocomposites as electrocatalyst for H2O2 production from oxygen. Ionics 2022, 28, 4045–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kinetic Order | k | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | 4.76 min−1 | 0.89 |

| Pseudo-first-order | 0.15 min−1 | 0.99 |

| Second-order | / | 0.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bouhoufani, Y.; Bensacia, N.; Kettab, A.; Mouni, L.; Riahi, R.; Lounici, H. A Sustainable Aluminium-Based Electro-Fenton Process for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment: Optimization, Kinetics, and Cost–Benefit Analysis. Processes 2026, 14, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010162

Bouhoufani Y, Bensacia N, Kettab A, Mouni L, Riahi R, Lounici H. A Sustainable Aluminium-Based Electro-Fenton Process for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment: Optimization, Kinetics, and Cost–Benefit Analysis. Processes. 2026; 14(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouhoufani, Yousra, Nabila Bensacia, Ahmed Kettab, Lotfi Mouni, Rim Riahi, and Hakim Lounici. 2026. "A Sustainable Aluminium-Based Electro-Fenton Process for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment: Optimization, Kinetics, and Cost–Benefit Analysis" Processes 14, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010162

APA StyleBouhoufani, Y., Bensacia, N., Kettab, A., Mouni, L., Riahi, R., & Lounici, H. (2026). A Sustainable Aluminium-Based Electro-Fenton Process for Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment: Optimization, Kinetics, and Cost–Benefit Analysis. Processes, 14(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010162