4.1. The Effect of Trapping Mechanisms

In an attempt to assess the individual contribution of the various trapping processes, three simulation runs were conducted. These four simulations were performed under the same operating conditions, which involved an injection period of one year and the total simulation time of 200 years. In

Table 11, the four simulation runs, the various trapping processes were incrementally incorporated and compared.

In case 1 (Structural + Solubility Trapping—Base Case), the trapping of CO2 mainly occurs through structural trapping below the caprock and solubility trapping as CO2 dissolves into the formation brine. In the injection phase and shortly after, most of the CO2 cloud is expected to be mobile, and it would be dependent on the geometry of the reservoir and the integrity of the top seal for trapping. Subsequent solubility trapping would increase the trapping as a result of the density difference created by the dissolution of CO2.

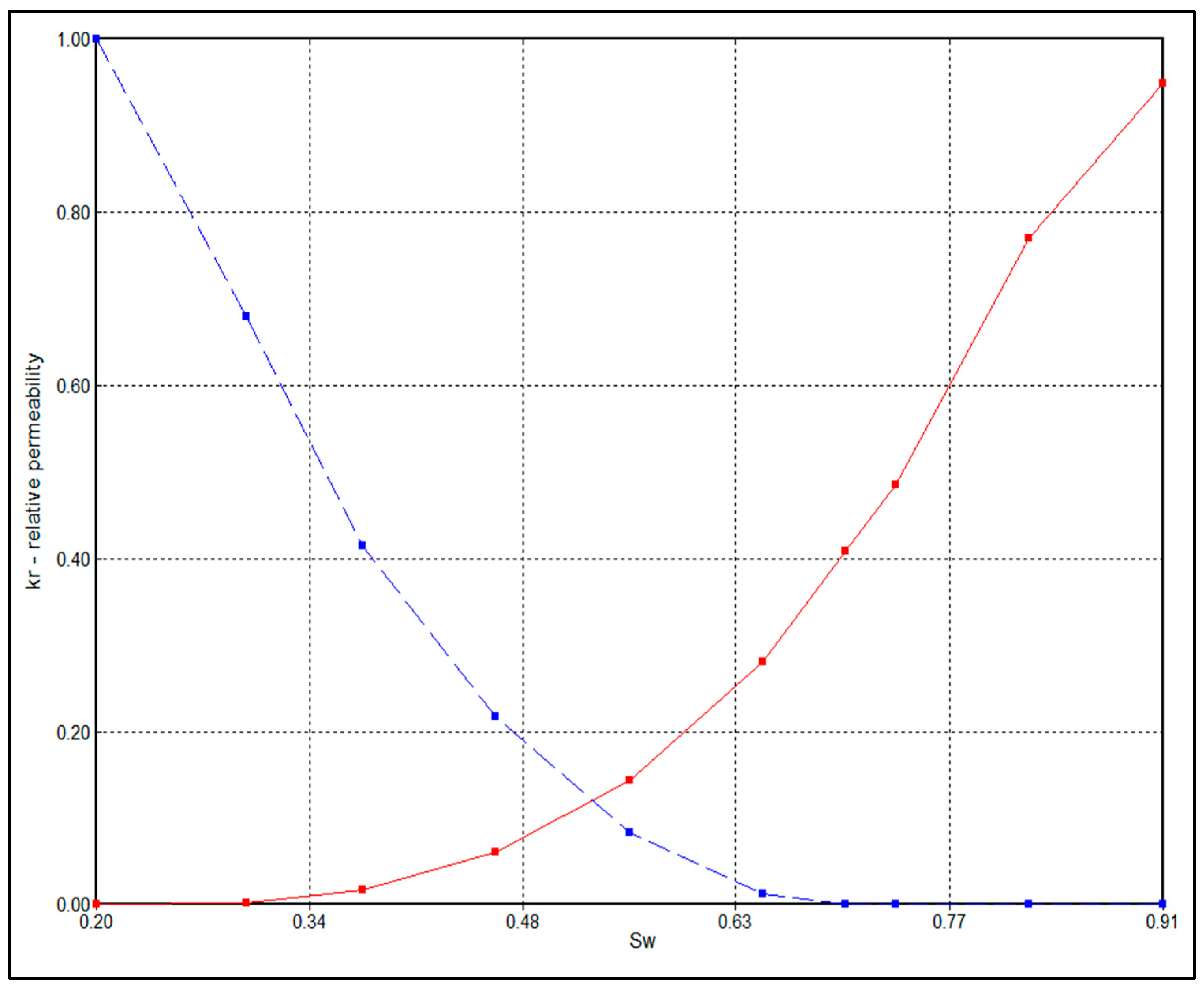

Case 2 (Residual Trapping by Hysteresis) adds capillary trapping. Following injection cessation, the imbibition of the brine into the pore space Results in permanent trapping of the CO2 ganglia that are disconnected. This rapid trapping process reduces the mobility of the plume, impedes upward migration, and increases the heterogeneity of saturations during the early injection period.

Case 3 (Mineral trapping and ion exchange) involves geochemical interactions between the dissolved CO2 and the minerals present in the reservoir, trapping the CO2 as precipitates of immobilized carbonates. Though it takes longer to develop, the trapping process provides the most secure method of CO2 burial. Ion exchange adds an extra step for the irreversible immobilization of CO2. At the close of the 200-year model run, the process provides considerably higher immobilization compared to the first two cases.

Case 4 (Vaporization + Mineral Trapping) considers all the above processes, as well as the vaporization of the formation water into the CO2 phase. As the CO2 interacts with the brine, the water vaporizes into the CO2 phase, thus increasing the salinity of the brine and the geochemical reactions. These high salinity levels enhance the supersaturation of carbonates and their rapid precipitation around the CO2 plume. On the other hand, the vaporization of water affects the permeability and the trapping capacity of the CO2 by increasing the trapping efficacy as the water saturation levels decrease around the major CO2 flow paths. This case illustrates the maximum improvement in the CO2 trapping capacity, as it immobilizes the maximum amount of CO2 and restricts the size of the detectable CO2 plume. In general, the improvement from physical trapping alone (Case 1) to complete immobilization involving trapping by capillary, geochemical, and vaporization mechanisms (Case 4) illustrates an increase in the degree of storage and pressure, and trapping capacity. These results show the benefit of incorporating trapping mechanisms involving petrophysics and geochemical processes during the development and evaluation of the site for carbon capture and storage.

Figure 4 indicates the average reservoir datum pressure for the four different CO

2 storage scenarios: the base case, hysteresis, hysteresis with mineral reaction processes, and hysteresis with both mineral reaction processes and vaporization. For all cases, during the injection period the pressures show a rapid increase representing the injection of the CO

2 and then follow a stable path once the injection ceases.

In the base case, the stabilized pressure is the lowest. This is due to the absence of other trapping mechanisms that allow more CO2 to be in the supercritical fluid phase, which is able to distribute more efficiently in the reservoir, thereby resulting in lower stabilized pressures.

Inclusion of hysteresis results in a slightly higher average pressure compared to the base case. Residual trapping causes a certain portion of CO2 to get stuck in the pore space, resulting in reduced permeability and mobility. Consequently, dissipation of pressure becomes less effective, thereby increasing the average pressure.

The maximum values of pressure occur in those scenarios that involve mineral reactions, both with and without vaporization. Mineral entrapment causes a reduction in dissolved CO2 content to form solid carbonate minerals, which in turn leads to a decrease in the pore volume, thereby causing high values of pressure in comparison to scenarios involving physical entrapment.

In addition, the introduction of vaporization has no marked impact on the overall trend of system pressure compared with that of the mineral system only scenario, which further implies that the contribution of vaporization is limited to the local fluid distribution around the well rather than influencing overall system pressure. On the other hand, the calculation results show that geochemical trapping enhances storage security yet simultaneously causes elevated storage system pressures.

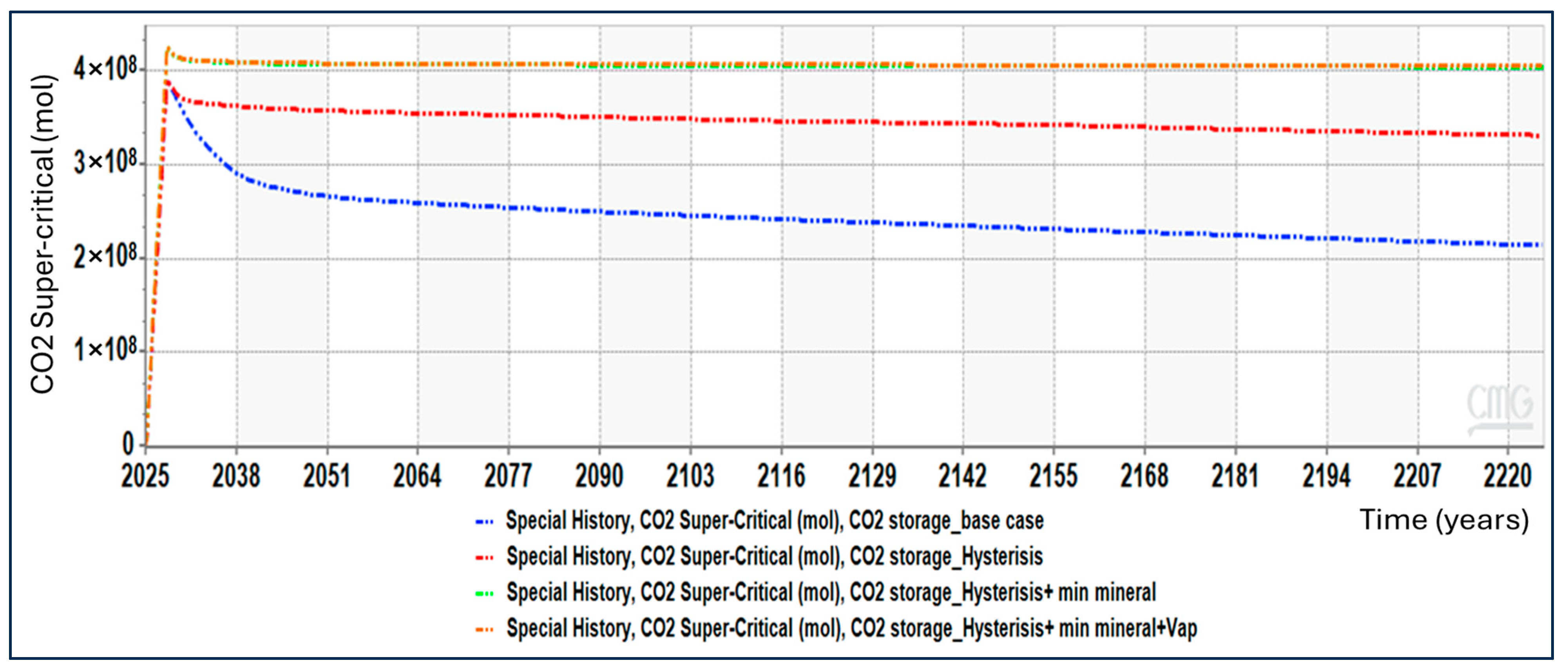

Figure 5 compares the evolution of supercritical CO

2 (free-phase CO

2) for four modeling cases: the base case, hysteresis only, hysteresis with mineral reactions, and hysteresis with mineral reactions and vaporization.

In the base case, supercritical CO2 shows the largest decline with time. Because no trapping mechanisms are activated, CO2 remains fully mobile after injection. Following injection shut-in, the supercritical CO2 plume continues to redistribute and migrate due to buoyancy and pressure dissipation. The observed reduction in supercritical CO2 therefore reflects plume spreading and loss of structural containment, not immobilization.

When hysteresis is enabled, the decline in supercritical CO2 is noticeably reduced. Residual trapping occurs during post-injection imbibition, converting part of the mobile CO2 into immobile residual gas. This limits further migration and stabilizes the supercritical CO2 volume compared to the base case.

The inclusion of mineral reactions further stabilizes the system. Although mineral trapping is a slow process, it gradually consumes dissolved CO2, indirectly reducing the amount of CO2 available to remain in the free supercritical phase. As a result, the supercritical CO2 curve becomes flatter over time, indicating enhanced long-term containment.

Finally, when vaporization is included, the supercritical CO2 remains the most stable and highest among all cases. Phase partitioning between aqueous and gas phases reduces effective CO2 mobility and limits free-phase redistribution. This combination produces the strongest immobilization behavior, even though injectivity may be reduced elsewhere in the system.

Figure 6 indicates that the CO

2 dissolved history is strongly dependent on the trapping mechanisms that are activated, thus illustrating the interaction between solubility trapping and residual, mineral, as well as phase effects. In the base case simulation, where only structural trapping is operational, the amount of CO

2 dissolved is at its highest level and continues to rise steadily with each annual simulation step. This is because a large amount of the injected CO

2 remains in the supercritical phase with high mobility, allowing considerable interaction between the phase and the brine in the formation.

When hysteresis is considered, the amount of dissolved CO2 is decreased compared to the reference case. Hysteresis favors the entrapment of the gas by forming disconnected ganglia that get immobilized during the drainage and imbibition processes. This reduces the amount of supercritical CO2 that is in contact with the aqueous phase. Although solubility trapping occurs in this case, the rate at which the dissolved amount increases and the amount at the end are much lower compared to the previous case.

The addition of mineral reactions results in a further decrease in the amount of dissolved CO2. In this scenario, the CO2 which diffuses into the brine will also react chemically to form solid carbonate minerals. This process, which moves CO2 from the aqueous phase to the mineral phase, competes directly with solubility trapping. Consequently, the concentration of dissolved CO2 tends toward a much lower equilibrium, which signifies the role of mineral trapping as a long-term sink for the build-up of dissolved CO2.

When the effects of vaporization are included on top of hysteresis and mineralization, the dissolved CO2 concentration is found to be the lowest among all cases. Vaporization changes the phase equilibrium and decreases the solubility of CO2 in the aqueous phase, and mineral reactions continue to consume dissolved species. The effect of all these processes is to limit the evolution of dissolved CO2 concentrations substantially after injection and cause the dissolved CO2 concentration to stabilize at a considerably early stage. This is because CO2 is being preferentially transferred to trapped and mineralized fractions. In summary, the graph indicates that the increased level of CO2 in solution is not necessarily related to strong storage security. Indeed, although the CO2 solution level is the highest in the basic scenario because solubility trapping is continually occurring, the basic scenario has no trap mechanisms for residual and mineral storage. Conversely, storage scenarios where hysteresis, mineralization, and vaporization occur display lower levels of CO2 in solution but improved storage security because multiple trapping mechanisms are at play.

In

Figure 7, it is evident that the distribution areas of CO

2 molality vary significantly between the four scenarios due to the increasing activation of secondary trapping processes. In the base case, where structural and solubility trapping alone are simulated, the dispersed zone of dissolved CO

2 is largest and most extensive, signifying high mobility and frequent interaction between the CO

2 phase and formation brine. As hysteresis (residual trapping) is incorporated into the processes, the areas with high dissolved CO

2 become restricted, signifying immobilization of injected CO

2 amounts earlier, which are, in turn, beyond the dissolution influence of fresh brine. Incorporation of mineral trapping decreases the areas and magnitudes of dissolved CO

2, signifying utilization of CO

2 amounts during geochemical reactions, forming solid carbonate minerals. The last option, involving vaporization + mineral trapping, has the lowest areas and magnitudes of dissolved CO

2. Water vaporization decreases the formation brine saturation and formation brine salinity, which are factors hindering the dissolution of CO

2.

Thus, these findings corroborate the fact that with the ever-increasing number of trapping mechanisms activated (from hysteresis to mineralization to vaporization), the dissolution phase of CO2 is constantly restricted and localized, which increases the overall containment security and further decreases the active dissolution plume extent within the reservoir.

Figure 8 displays a comparison between the capillary-trapped CO

2 saturation (Sgr) maps after 200 years, including four trapping geometries. Residual trapping behavior is very much dependent on the immobilization processes occurring during and after the CO

2 injection.

In the base case, the hysteresis is off, and consequently, most of the injected CO2 is mobile. The CO2 plume is buoyant and accumulates structurally without much permanent trapping. Consequently, the reservoir has zero Sgr, which suggests a high potential for long-range migration if not trapped by structure.

When hysteresis is considered, capillary trapping becomes active after injection is completed and brine starts to imbibe back into the rock. The CO2 zone moves very quickly and is trapped as individual ganglia. This creates a sharp, crescent-shaped zone of residual CO2 surrounding the injection zone, which accurately reflects fluid invasion and displacement. In this example, it is evident that the very strong trapping effect is associated with the first line of immobilization following shut-in.

With the addition of mineralization, the result is a more focused and smaller trapped plume. The mechanism of mineralization adds carbonates to the system by reacting part of the dissolved CO2 into more stable carbonates, particularly near the injection point. As more mobile and dissolved CO2 is consumed by reaction, the amount of CO2 left to migrate and develop new locked clusters decreases. Decisions based on the volume changes of Sgr are a straightforward measure of increased long-lasting trapping.

Lastly, the extent of the most compact plume is attained by the vaporization + mineral trapping mechanism. The result of water vaporization into the simulated CO2 flow is to reduce brine saturation and increase salinity. This regime is interpreted to moderately influence capillary pressure and modification of the respective permeability, delaying the start of residual trapping but impeding the expansion of the plume. Although the difference is slight, the front is not merely more contracted, but also fixed, and has little possibility of buoyancy-assisted movement.

In

Figure 9, the pH distribution after 200 years is shown for the four trapping processes, illustrating brine acidity changes with increased immobilization processes. In the base case, the pH value is constant and basic over the entire domain because very little CO

2 is soluble within the formation water. As a result of the supercritical mass of CO

2 being trapped structurally, and when little carbonic acid is generated, the geochemistry of the formation brine is not significantly affected. In the hysteresis-only case, the inclusion of residual trapping is also ineffectual, and as most of the CO

2 is isolated in unconnected pockets, little interaction takes place, and consequently, the geochemistry is unaffected.

A significant transition is realized when mineral trapping is enabled. In the case of hysteresis + mineralization, a strong low-pH area is realized around the CO2 blob, signifying active dissolution of CO2. When CO2 is dissolved, it combines with water to form carbonic acid, which is a strong sign of carbonates forming. The sour areas are also known to show where geochemical transformations are attained, which translates to converting dissolved CO2 into a more stable form. As of 2225, the areas are still sour, signifying a high level of geochemical trapping.

The hysteresis, mineralization, and vaporization process further exacerbates such phenomena. The vaporization of water into the CO2 phase causes dehydration and increased saturated brine and salinity within the surrounding areas of the injection site, which favors the dissolution and reaction rate of CO2. Consequently, a greater and more active zone of acidity is produced compared to the case involving mineralization. This suggests not only increased dissolution of CO2 but also an intensified geochemical reaction process. Overall, it is evident from the comparison that the extent of geochemical interaction between CO2 and rock is very important to control the changes of pH. When only the physical trapping mechanism is used, there are negligible chemical changes. With the inclusion of mineral reactions, it initiates the long-term process of stabilization. When further consideration is given to the effects of vaporization, dissolution and conversion processes are further increased, which also increases the ability to buffer. Therefore, it can be said that the changes in pH are very significant to assess the efficiency of chemical trapping.

Noticeable change happens when mineral trapping becomes a factor. Looking at the hysteresis + mineral scenario, the strong Acidic Halo develops around the CO2 patch. This indicates the locations where the dissolved CO2 reacts with the water to form carbonic acid.

The regions demonstrate the onset of the irreversible storage process of the CO2, where the gas migrates from being a fluid to a solid mineral form. This clearly demonstrates how mineral trapping factors directly improve storage efficiency by reducing the overall amount of free CO2 in the simulation.

The greatest degree of geochemical influence takes place when the degree of vaporization is estimated. The highest degree of the hysteresis + mineral + vaporization effect demonstrates the largest degree of acidification. Water vaporization to form CO2 effects high salinity of the brine and decreases the saturation of the aqueous systems. The dissolution of the CO2 accelerates mineral reactions. This contributes to a larger chemically altered region together with a faster transition to a steady-state mineral form. The pH effect demonstrates the degree to which the vaporization influence accelerates the immobilization of the chemical processes. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that pH sensitivity serves as a highly informative factor for the efficiency of geochemical trapping in CO2 storage. In the case of scenarios without mineral reactions, there is very little variation in pH values, demonstrating the ineffectiveness of physical trapping in converting CO2 into a less harmful form over a long period of time. When chemical processes become operational, the acidity in the reservoir develops in a manner proportional to dissolution rates and the range of mineralization. The expanded region of acidity in the scenario of vaporization enhancement further substantiates the optimistic effects of combining different mechanisms of trapping in terms of both magnitude and rapidity for permanently storing CO2.

4.3. The Effect of Different Rock Types, Salinity and O2 Impurities

Given the importance of the mineral composition of the reservoir rock and the aquifer to the efficiency of dissolution, ion exchange, and mineral trapping, a sensitivity test has also been conducted to assess the role of rock types towards CO2 long-term containment. In consideration of further geochemical reactions triggered by oxygen impurities within the injected CO2 stream, which has the ability to expedite mineral dissolution and further influence brine chemistry and carbonate precipitation, research has also assessed the role of oxygen impurities.

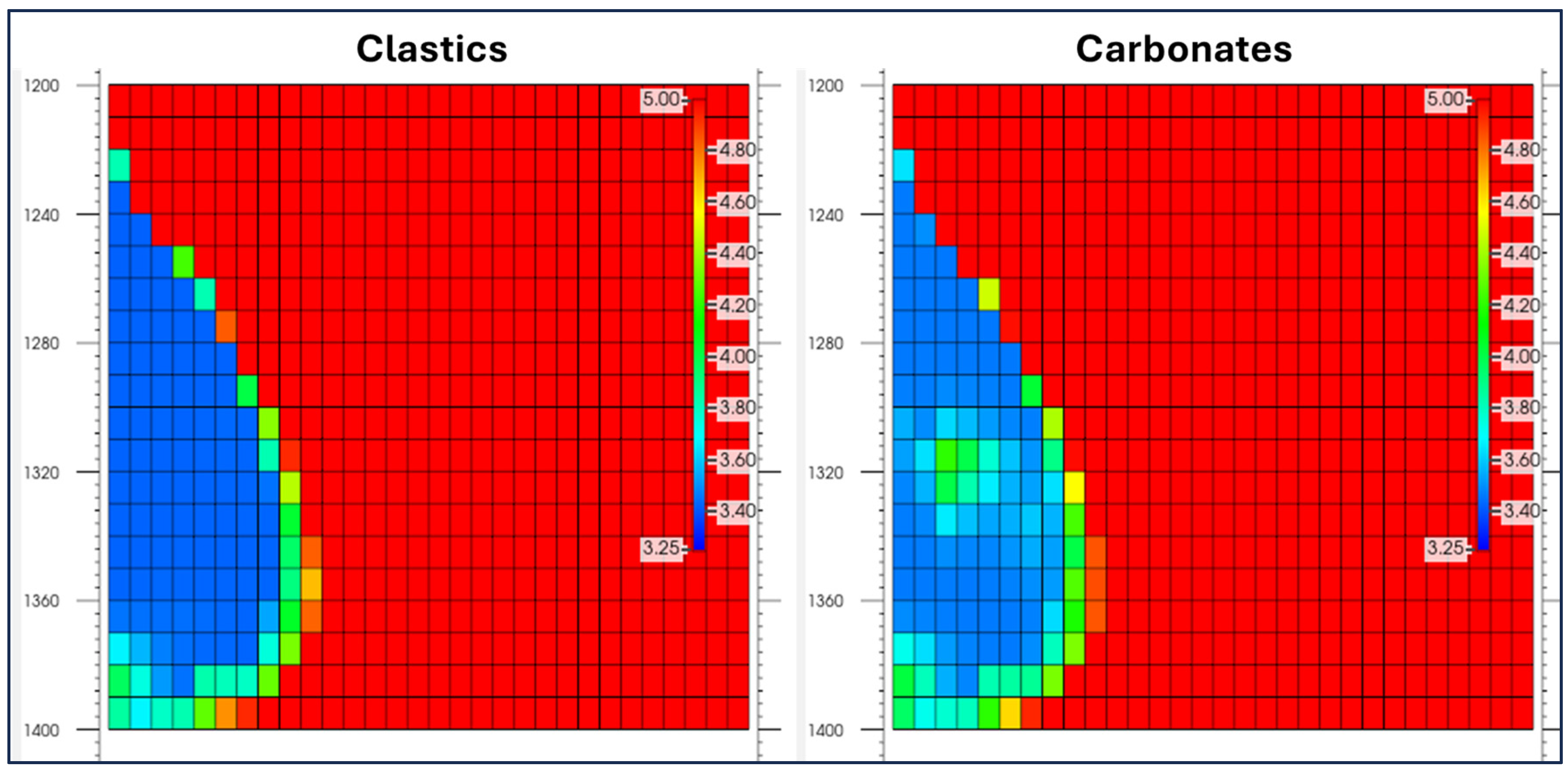

4.3.1. Clastics vs. Carbonates

Figure 14 presents a comparison of the pH distribution after 200 years for the two sets of rocks reactivity assumptions. In both cases, there exists a clear region of acidity in the vicinity of the CO

2 plume due to the dissolution of CO

2 into the brine, thereby forming the initial steps of the carbonic acid. There seems to be a variation in the magnitude of the acidity in terms of spatial distribution. In

Figure 14 the Clastics (sandstone) scenario, the region of dissolution seems to be less in width compared to the carbonates scenario. This suggests the rates of geochemical processes to be slower in the traditional carbonate scenario. This indicates a lower degree of action between the fluid phases in the Clastics scenario.

In contrast to the previous case, when the concentrations of the carbonate mineral phases of higher reactivity become higher, the area of the low pH region significantly expands. An extended acidic region points to a higher dissolution speed as the carbonate mineral phases actively take parts in the neutralization of dissolved CO2 in the region. At the same time, the region promotes the dissolution of CO2 into carbonate mineral phases. A higher degree of dissolution in the carbonate mineral phases indicates the improved capability of the trap to confine CO2 in the long term since a higher degree of dissolution of CO2 takes place in the trap.

Taken together, these findings make it clear that the carbonate mineral composition of the rock plays a pivotal role in the long-term storage of the CO

2 as stated in

Table 13. A rock that has high reactive carbonate not only helps in the rapid neutralization of the acid but also allows more rock to be a contributing factor in mineral entrapment. Vaporization makes this even more efficient by allowing the brine to have a higher salinity level. This would allow more CO

2 to undergo a chemical change to become a more stable form over a long period of time.

4.3.2. Effect of Salinity

Figure 15 demonstrates the molality distribution of CO

2 in carbonate formations with varying values of calcite availability: Ca = 5000; 50,000; and 200,000. In the minimum carbonate scenario (Ca = 5000), the molal concentration of dissolved CO

2 is highest around the edge of the CO

2 plume. The molal gradient in the figure is very sharp and localized. The effect of a small contact area between the supercritical fluid plume and the aqueous phase suggests that dissolution-controlled trapping mechanisms may be less favored.

With the enhancement of the calcite concentration to Ca = 50,000, the region of high CO2 molality definitely extends to a larger area around the edge of the plume. This enhancement of molality demonstrates a higher dissolution of CO2. This is particularly linked to the high rates of reaction/mixing pathways supported by high mineral concentrations. With high concentrations of carbonate surface regions being more susceptible to dissolution, the interface between the plume and the brine will extend, thereby enabling a higher dissolution of the CO2 from the mobile gas phase to the chemically dissolved phase.

The high carbonate case (Ca = 200,000) exhibits the strongest dissolution characteristics. In the high carbonate case simulation, the molality plume extends further into the reservoir. The larger dissolution interface in the high carbonate case simulation also indicates the enhancement of the geochemical effect. More reactive interfaces continue to be produced due to the dissolution of carbonate material. Such dissolution further enhances the solubility of CO2 gas. Consequently, the storage safety increases since more of the stored CO2 gas moves to the less mobile aqueous phase.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the presence of carbonate-rich formations significantly enhances solubility trapping capabilities. The higher reactivity of the mineral content would lead to a larger contact surface between the CO2 molecules and the brine. Additionally, the dissolution rates would be higher. These characteristics would allow the dissolved CO2 to extend beyond the immediate well location. Indeed, the dissolution of the CO2 into the brine makes it denser. At the same time, there would be no risk of buoyancy-related leakage. This would be accompanied by the conversion of CO2 into solid carbonate minerals.

Figure 16 presents the residual CO

2 saturation distribution after 200 years for carbonate reservoirs with increasing calcite abundance (Ca = 5000; 50,000; and 200,000). In every case, residual trapping occurs primarily along the trailing edge of the CO

2 plume, where gas has displaced brine, migrated outward, and subsequently become immobilized as pore-scale ganglia. However, the magnitude and areal extent of this trapped zone evolve significantly as a function of carbonate mineral availability. In the low-carbonate case (Ca = 5000), the plume footprint is relatively narrow and only the immediate zones swept by the plume show meaningful residual gas saturation. Because the formation has limited reactivity, dissolution is weak and only a small amount of CO

2 transfers into the brine. As a result, the supercritical plume retains a more compact geometry, and snap-off trapping is constrained to a limited volume.

When carbonate availability increases to Ca = 50,000, the spatial coverage of trapped CO2 increases and the saturation gradients become more smoothly distributed. This is attributed to enhanced dissolution and fluid rearrangement along the plume boundary. As CO2 dissolves and weakens buoyant drive, plume migration slows and lateral expansion increases, creating broader regions of capillary snap-off and disconnection from the mobile phase. Thus, the enhanced geochemical reactivity indirectly amplifies residual trapping by encouraging more uniform plume thinning and more sustained contact with brine-filled pore structures.

The strongest trapping response is observed in the most carbonate-rich case (Ca = 200,000), where the residual CO2 footprint expands dramatically and the saturation contours reach deeper into the reservoir. With a highly reactive matrix, continuous dissolution along the plume flanks increases brine–CO2 contact efficiency and prolongs gas–liquid interface exposure. This drives extensive disconnection of CO2 threads into isolated clusters, significantly boosting the volume of residually immobilized gas. Moreover, the broad spread of trapped gas indicates that dissolution-mineralization reactions are actively reshaping flow pathways, reducing vertical buoyant rise and encouraging lateral trapping instead of plume coalescence under the caprock.

Importantly, this behavior demonstrates that residual trapping is not purely physical in carbonate reservoirs—it is strongly coupled to geochemical processes. Greater carbonate availability leads to more dissolution, weakening the supercritical plume and promoting immobilization. At the same time, increased dissolution exposes new mineral surfaces, reinforcing a feedback loop where CO2 progressively transitions into less mobile states. Therefore, as mineral abundance increases, residual trapping evolves from being a short-term containment mechanism to becoming a major contributor to long-term plume stabilization. This synergy between capillary forces and dissolution means that carbonate-rich reservoirs provide more robust early and intermediate trapping security, even before mineral precipitation dominates.

Ultimately, these results show that carbonate formations do not just enhance chemical storage; they also substantially strengthen the physical immobilization of CO2 through dynamic plume redistribution and improved contact efficiency. This dual trapping reinforcement underscores why carbonate reservoirs are among the most effective geological formations for CCS, offering secure, multi-mechanism immobilization that continues to improve with time.

Figure 17 demonstrates the progression of the extent of the brine phase change due to the injection of CO

2 in carbonate formations having different amounts of calcite. In the scenario having the lowest Ca concentration (Ca = 5000 ppm), the extent of the chemical change in the acidic phase can be considered to be more localized. There may be more dense regions of low pH values close to the boundaries of the plume. This may be due to the nature of the rock being less buffered.

There would be the formation of a sufficient amount of carbonic acid due to the dissolution of the higher amounts of dissolved CO2. But the rock would have less capability to react.

With the higher carbonate concentrations reflected by the corresponding Ca = 50,000 values, the low-pH region extends both horizontally and in-depth. An enlargement of the region suggests more aggressive interactions between CO2, the brine phase, and the rock mass. More calcite interfaces translate to favored dissolution reactions for the carbonate rock. Such chemical reactions result in a higher consumption of the formed carbonic acid. Hence, the corresponding regions representing the acidification process appear more distributed.

The largest degree of acidification takes place in the high-calcite case (Ca = 200,000). In this simulation case, there exists a very large amount of the plume interface region in the highly lowered regions of pH values. Such a degree of reactive carbonate chemistry clearly points to a very reactive carbonate system in which a reactive surface of the mineral undergoes continuous dissolution. At the same time, the reacted carbonate mineral surface keeps enough path length ahead to allow migration of the carbonic acid before being consumed. Additionally, the widened halo of the degree of acidification clearly indicates that a larger portion of the reservoir undergoes the action of the immobilization.

Table 13 summarizes these findings demonstrate a positive and definite influence of carbonate mineral content on the strength of geochemical entrapment.

With higher Ca concentrations, there would be a greater dissolution interface for the dissolved CO2 to react with the rock minerals, thus hastening the conversion of mobile CO2 into solid form. Such a continuous buffering action would therefore promote the permanence of storage. The existence of carbonate mineral environments would therefore have outstanding benefits in the storage of CO2 in the sense that storage would not only occur efficiently but also in a manner that emphatically guarantees storage permanence.

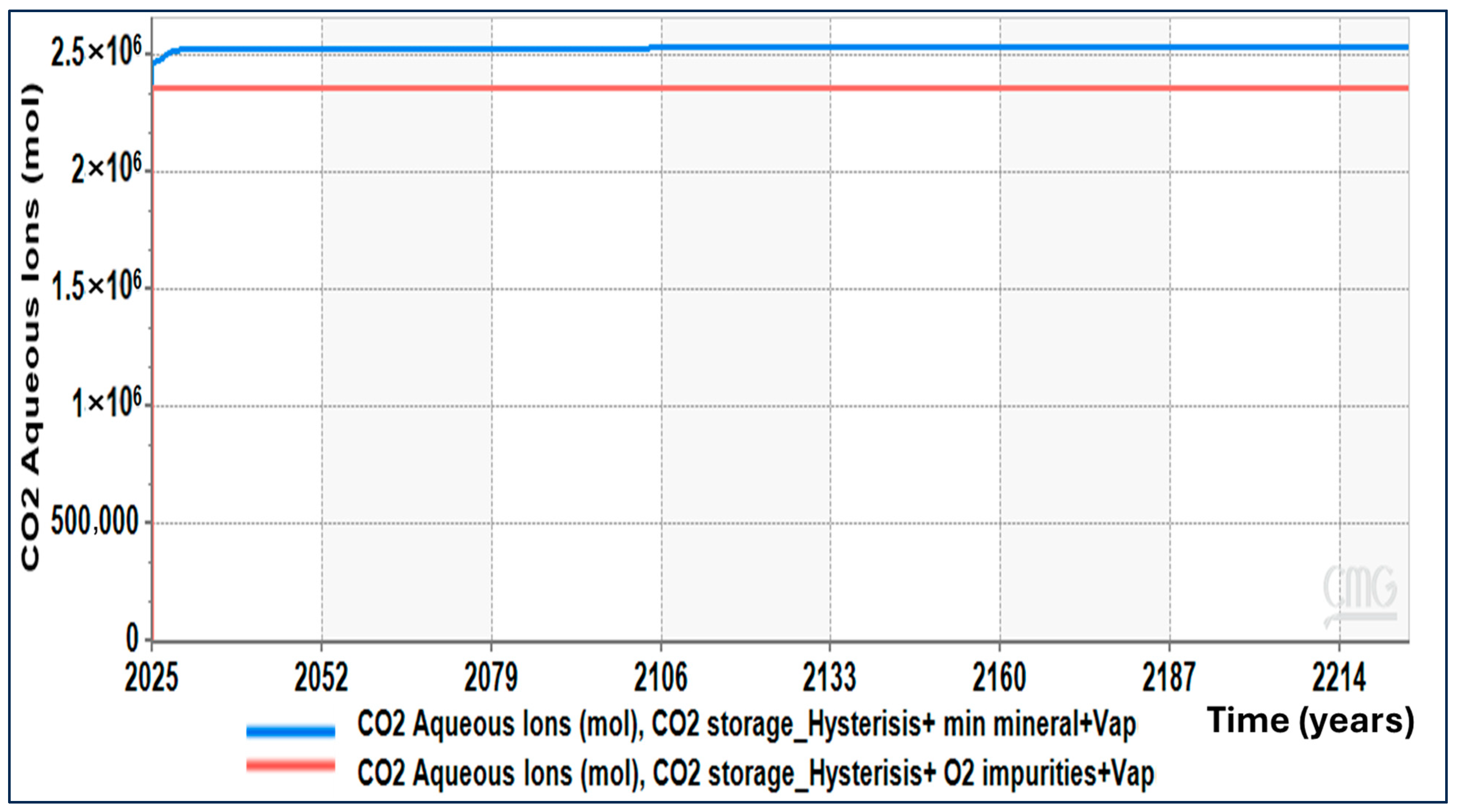

4.3.3. Effect of O2 Impurity

This involves two scenarios, the pure CO

2 stream with processes of hysteresis, mineralization, and vaporization, while the second involves the same gas trapping configuration but incorporates the effect of O

2 impurities. the total mass of the CO

2 injection process has remained more or less the same. But there would be a slight variation in the proportion of different processes. The curves of the two for the trapped CO

2 in

Figure 18 would be almost overlapping. This would further reveal that the effect of the presence of oxygen would have less bearing on the migration of the plume. Also,

Table 14 shows a comparison between the two cases.

In both examples, the supercritical CO2 increases dramatically in the 1-year injection phase but falls off very rapidly in the latter phases as the plume evolves into a new equilibrium dominated by residual trapping.

A few decades after shut-in, the level of the supercritical phase has reached a steady-state low but equal value in both examples, verifying that the overall dynamics of plume-scale fluid movement are largely controlled by rock properties, regardless of minute gas composition differences.

More significant disparities exist in the geochemical aspects of gas trapping. A qualitative analysis of the mineralized CO

2 profiles in

Figure 19 indicates that the presence of oxygen results in a slightly higher mineral trap capacity over the entire 200-year simulation period. In the scenario without impurities, the mineralized CO

2 concentrations grow very aggressively shortly after the gas injection but taper off subsequently when the most reactive mineral surface sites become exhausted.

With the inclusion of O2, the mineral CO2 curve always remains above the base case scenario. This implies that oxygen causes additional mineral dissolution and chemical reaction mechanisms that lead to more divalent ions being released into the brine. These chemical reactions extend for a longer period of carbonate mineral formation. Consequently, a relatively higher portion of the CO2 becomes trapped in the solid mineral phases. The practical effect of the oxygen-filled stream is the additional push toward the more permanent trap.

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 show that the figures of dissolved & aqueous ionic CO

2 (molality & carbonate & bicarbonate ions) add to the picture. In both cases, the immediate effect of the injection was a rapid increase in the concentration of dissolved CO

2 in the plume. With the passage of time, however, the figures show a slight variation in the trend of the concentrations of dissolved & ionic CO

2. In the no oxygen case, the concentration remains a bit higher.

This occurs in agreement with the higher mineralization present in the O2 scenario. With the higher conversion of dissolved CO2 to solid carbonate phases, there will be less remaining in the dissolved form. Essentially, the presence of O2 does not inhibit the dissolution of CO2. Instead, the dissolution of CO2 in the presence of oxygen triggers a faster chemical reaction to remove the dissolved CO2 into the solid phases.

These trends together indicate that the influence of O2 impurities on total storage capacity or physical immobilization at the Early Time (Supercritical + Residual) is not significant but affect the distribution of chemically trapped CO2 between dissolved or ionic form and mineral form. The scenario of pure CO2 keeps more CO2 in the dissolved phase, while the scenario of mixtures of CO2 + O2 keeps a slightly higher portion of CO2 in mineral form.

For secure storage, however, the re-partitioning of CO2 in the form of a change from dissolved CO2 to solid mineral carbonates is a positive development for storage security because the mineral form of CO2 will remain in storage permanently. The oxygen-rich stream will therefore induce a small but significant positive effect in terms of the permanence of the trap. Otherwise, the path of the trap remains the same.

4.4. Simulation Running Time

The plot provides an outline of the simulation run times for the CO2 storage scenarios ordered with respect to increasing run time, demonstrating the cumulative effect of increasing levels of complexity. It should be noted that the simplest scenarios, the “Base” and the “Hysteresis Only” simulation, have the shortest run times because these examples are relatively simple and consist only of basic multiphase fluid dynamics with little or no nonlinear couplings. Within these example scenarios, the migration of the CO2 is primarily controlled by structural trapping and the system dynamics allow for the use of very large timesteps and fast convergences.

Figure 22 shows the running time of the different scenarios studied. The coupling of mineralization, hysteresis, and vaporization causes a pronounced increase in the runtime. When simulating mineral entrapment, both multiphase flow processes and geochemical reactions, like aqueous speciation, have to be linked, whereas simulations involving vaporization imply additional phase equilibrium calculations. Despite this complexity, the solver still has to deal with a highly coupled nonlinear problem, which increases computational time.

Carbonate systems involving vaporization but having low Ca concentration resolution (Ca resolution of 5k) have been found to have intermediate simulation times. It should be noted that although calcium chemistry is simulated at a relatively coarse resolution, reactions involving carbonate minerals remain active. This signifies that even when Ca resolution is very coarse, there is a large computational overhead compared to other physical trapping mechanisms.

The added O2 species further raises the simulation time due to additional equations for mass balances and the speciation of the aqueous and gas phases. The expanded chemistry scheme introduces numerical stiffness and limits time stepping.

An increase in the Ca concentration solution to a level of 50k in clastic sedimentary geologies, combined with vaporization, leads to a higher runtime. The Ca concentration tracing process increases the species and reactions in the aqueous component, increasing the interaction between the hydrologic transport process and geochemistry. This increases non-linearity and the number of iterations.

The runtime for the systems involving vaporization, Ca, with a concentration of 50k, is slightly higher for the carbonate systems compared to clastic systems. This is expected, as the reactivity of the systems, along with the rock-fluid-chemistry interactions, makes the systems stiffer, even for a moderate level of chemical resolution.

In these cases with intermediate timesteps, the longest running times are those with mineralization, vaporization, and long simulation times of 500 and 1000 years. This is because the long simulations entail more timesteps to account for the slower reactions in mineral trapping, CO2 dissolution, and geochemical equilibration. This result clearly shows that the effect of simulation time is significant in computationally expensive problems involving geochemistry.

The most computationally intensive problem is the carbonate system with vaporization and high Ca concentration resolution (Ca 200k). In this problem, strongly reactive carbonate minerals, detailed aqueous Ca chemistry, and kinetic discretization all interact to produce a strongly nonlinear and coupled problem. A large number of calculations of chemical reactions per time step make the problem stiffness and result in the largest runtime as shown above. In particular, the figure shows that there is a tradeoff between physical and geochemical fidelity and speed for simulations involving CO2 storage.

While structural trapping and hysteresis simulations are computationally inexpensive, mineralization, multi-component phase simulations, simulations involving tracking the Ca concentrations, longer-term prediction, and higher geochemical resolution are runtime intensive. Such findings illustrate the need for appropriate model complexity choices depending on the context of the simulations, especially when performing large-scale sensitivity analyses.

4.5. Future Work and Recommendations

Though this work brings out certain aspects of trade-off and computation cost for CO2 storage simulations with significant benefit, several important extensions are proposed for improving the realism and applicability of the modeling system.

First, the simulation studies should be extended to simulate depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs. In view of the complexity introduced by the presence of residual hydrocarbon saturation, wettability, depletion, and existing wells, depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs are much more complicated than saline reservoirs. Yet, by simulating depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs, two processes, namely, storage and Enhanced Recovery, can be assessed together.

Secondly, processes of saline precipitation also need to be considered in future modeling exercises. CO2 injection may cause water vaporization and salt precipitation around injection wells. This could potentially lead to a reduction in porosity and permeability and even loss of injectivity. Modeling processes and mechanisms associated with salt precipitation and dissolution is critical in capturing accurate predictions around injection wells and long-term storage.

Third, facies-controlled geological models with a proper degree of complexity should be used instead of simplified models. The facies-controlled variations in porosity, permeability, mineralogy, and capillary properties are essential for CO2 plume growth, residual trapping, and geochemical processes. The use of facies models built from seismic information, well logs, and core data would be an important improvement in the simulations of CO2 storage processes.

In this regard, the incorporation of site-specific static geological models from actual storage formations is highly encouraged. In this respect, site-specific static geological models involve detailed structural frameworks, stratigraphy, faults, as well as mineralization, offering a rather realistic approach for subsurface conditions. Worth noting is the consideration that the computation for actual static geological models is expected to take significant processing time, potentially ranging from many hours to several days. This is brought to light as a realistic consideration for large-scale sensitivity analyses or uncertainty analyses employing fully detailed site-specific static geological data.

Lastly, in light of the high computational expense required for simulations involving high physics and geochemistry, future studies should investigate computational optimization techniques. For example, adaptive meshing, focused activation of geochemical reactions, or hybrid machine learning and simulation flows could be useful techniques to improve computational tractability.