Analysis on the Transient Synchronization Stability of a Wind Farm with Multiple PLL-Based PMSGs

Abstract

1. Introduction

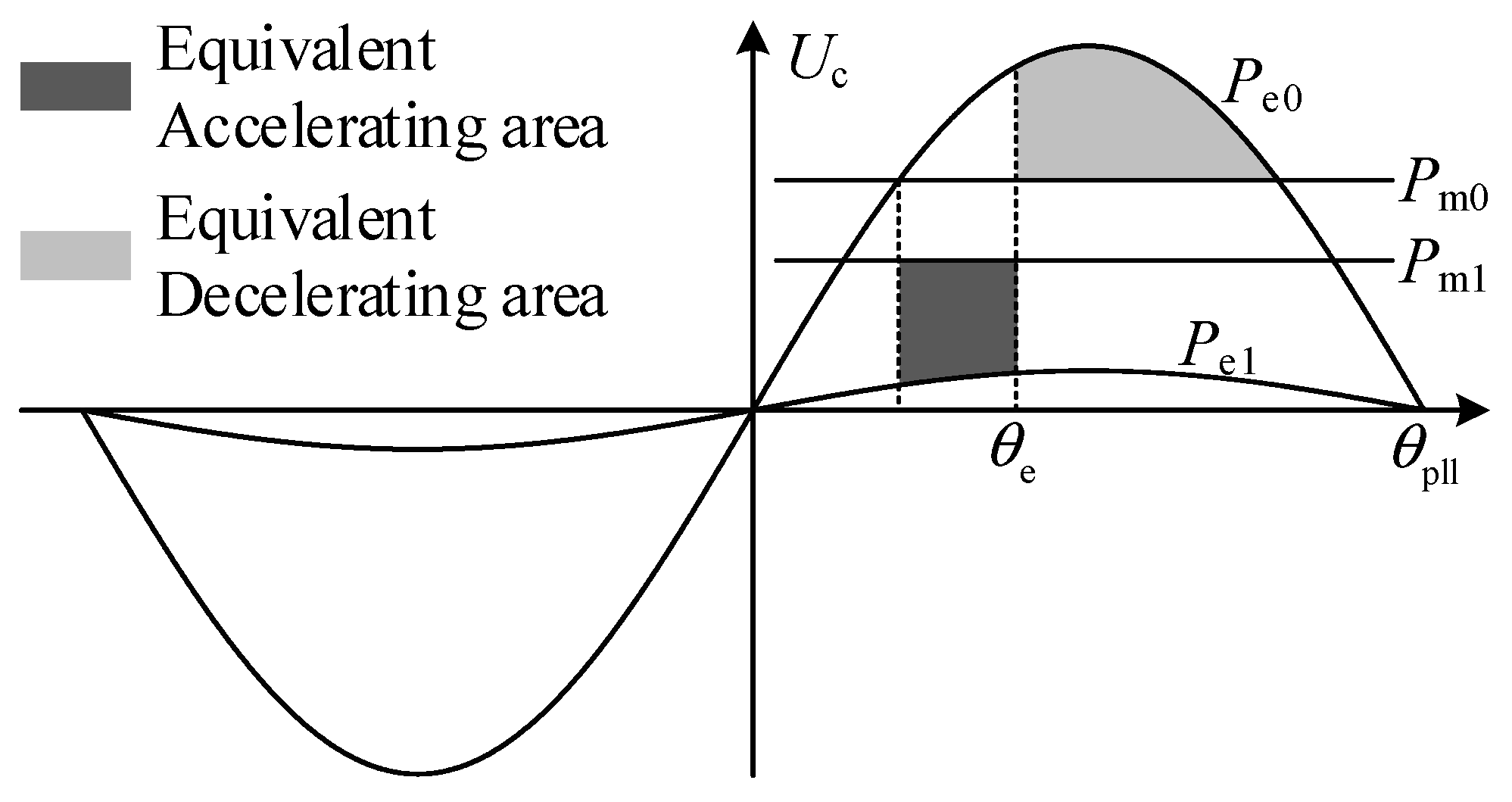

- A single-machine equivalent model was developed for analyzing transient synchronization stability in complex wind-farm networks. It introduces equivalent accelerating and decelerating areas as key measures of wind-farm transient stability.

- The mechanism by which interactions among multiple wind generators induce transient synchronization instability is clarified, considering generator dynamics, generator count, and network topology and parameters.

- The mechanism by which transient synchronization instability is induced by interactions among multiple wind generators is clarified, with generator dynamics, generator number, and network topology and parameters all taken into account.

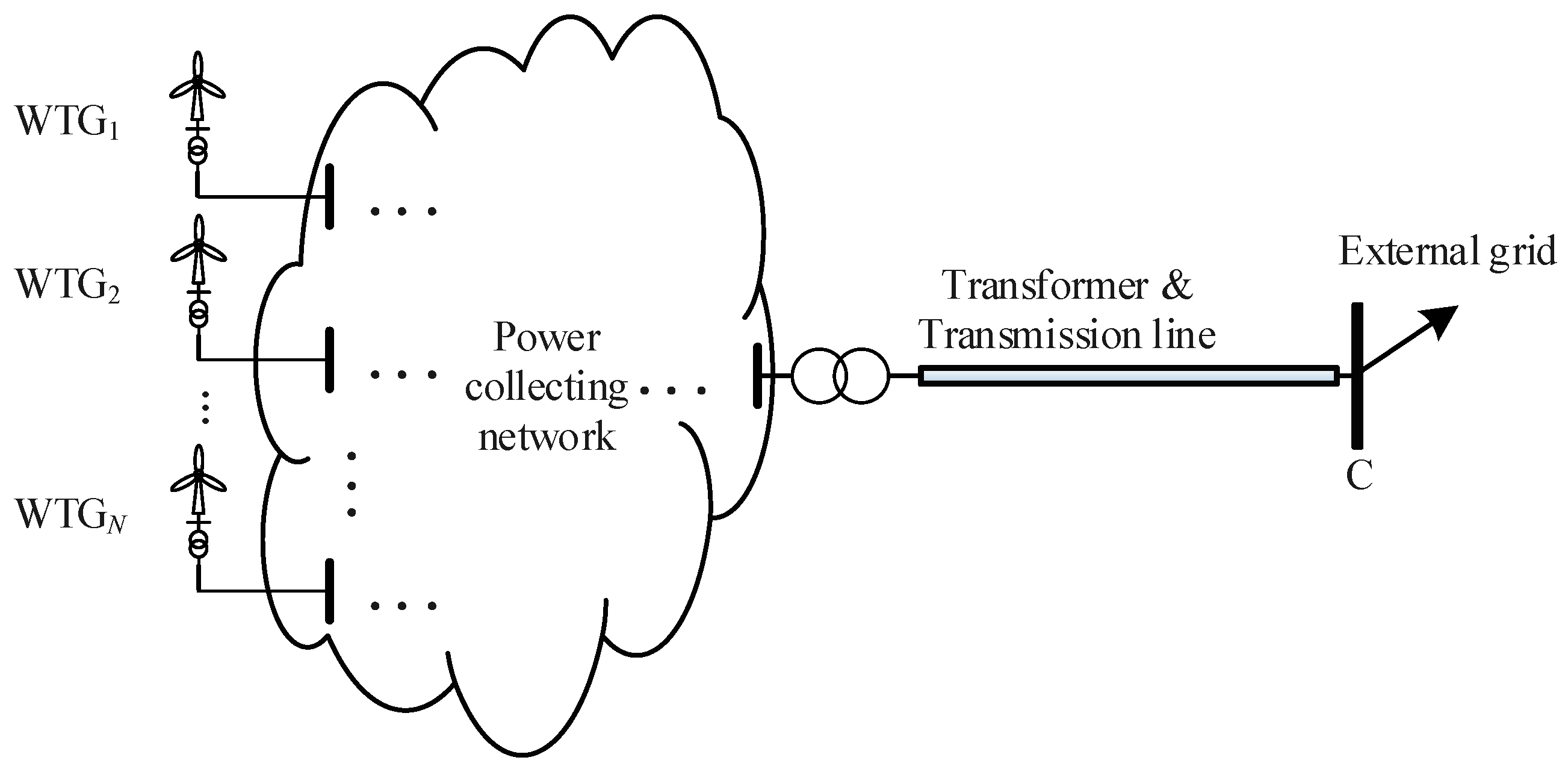

2. Aggregated Wind-Farm Model for Transient Synchronization Stability Analysis

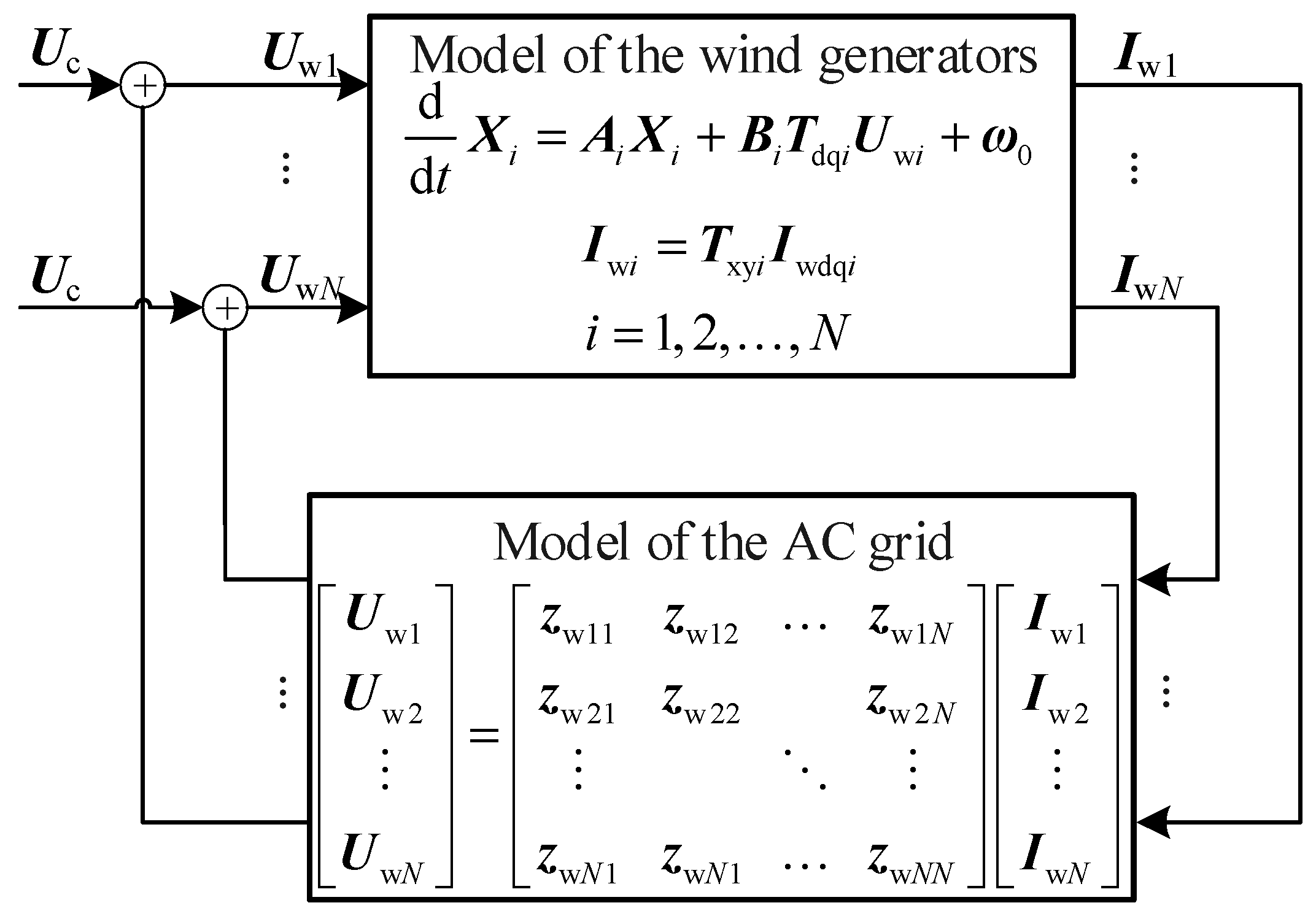

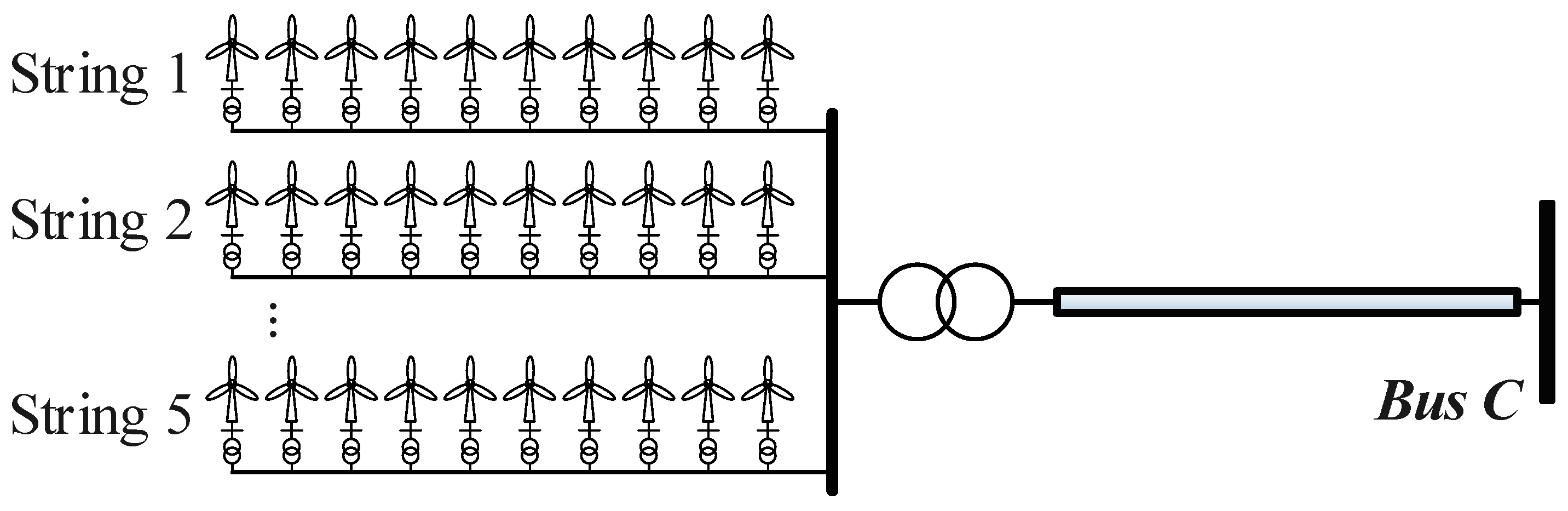

2.1. Wind-Farm Modeling for Transient Synchronization Stability

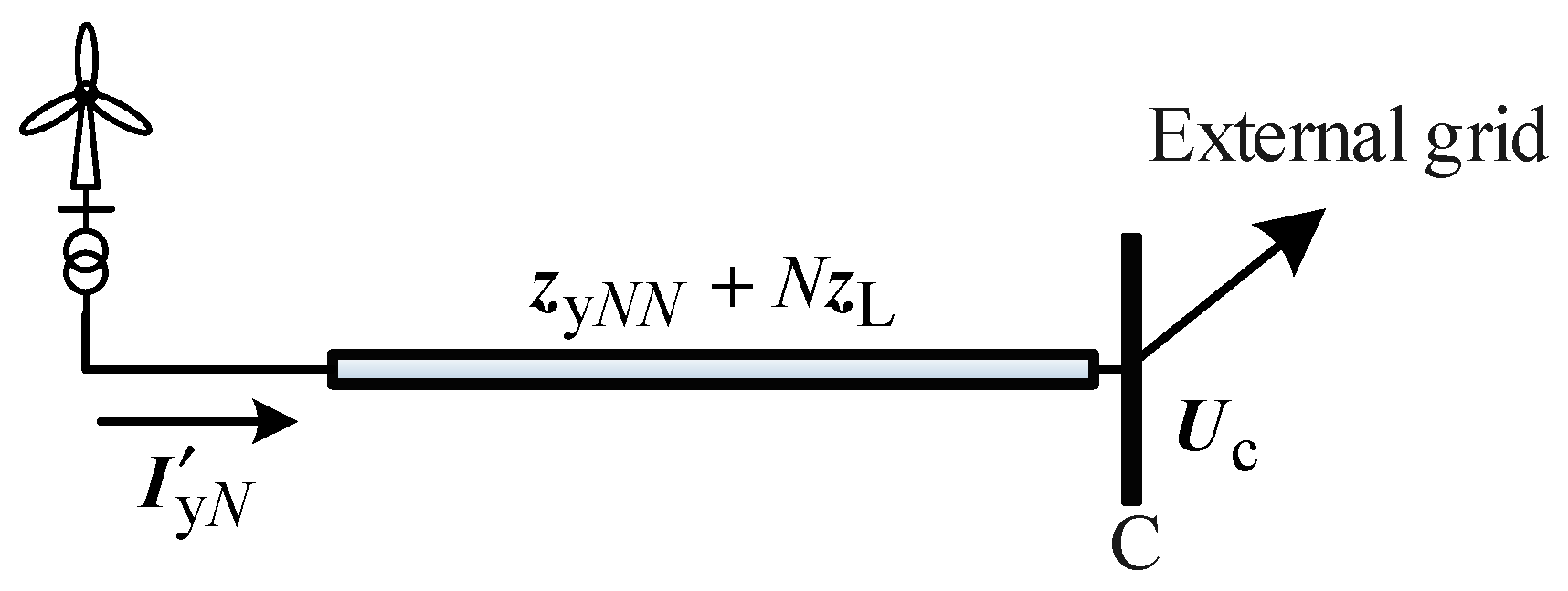

2.2. Aggregation of the Wind-Farm Model

3. Mechanism Analysis of Transient Synchronization Instability in Wind Farms

3.1. Impact of Generator Dynamics on Transient Synchronization Stability

3.2. Impact of Network Topology and Parameters on Transient Synchronization Stability

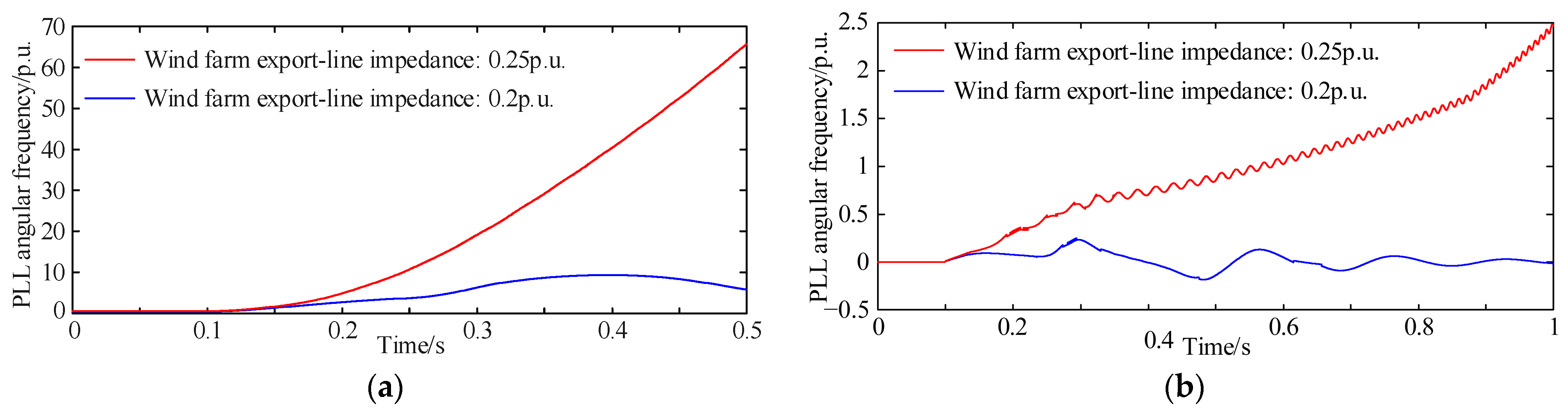

- For a fixed number of generators, a larger export-line reactance xL increases X, which weakens the wind farm’s transient synchronization stability.

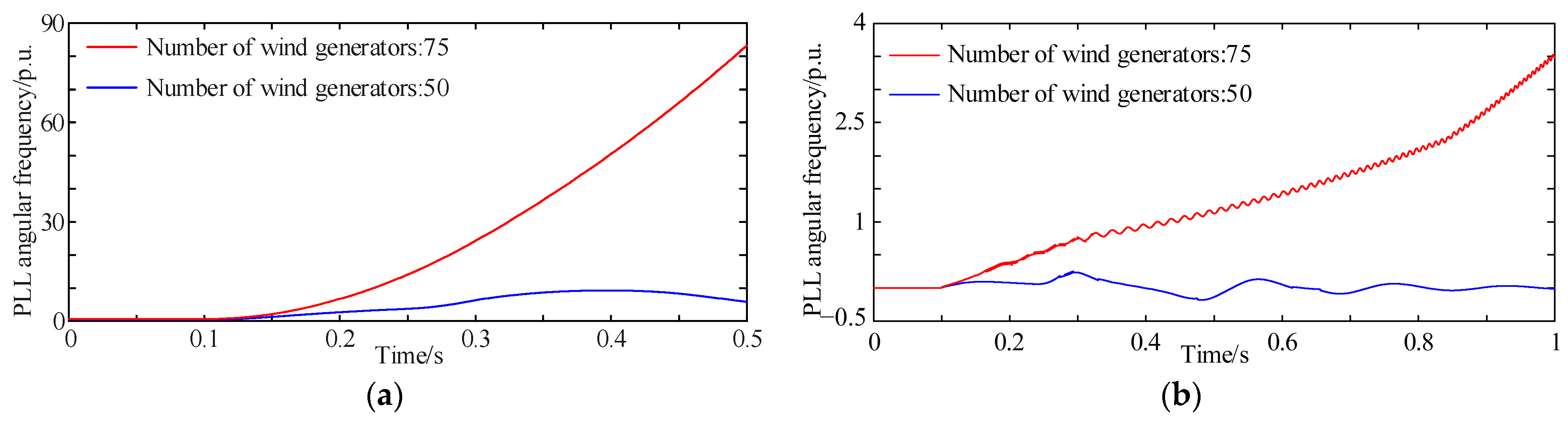

- Since the internal collection-line impedance is typically much smaller than that of the export lines, for a given xL, a higher number of generators increases X, further reducing transient synchronization stability.

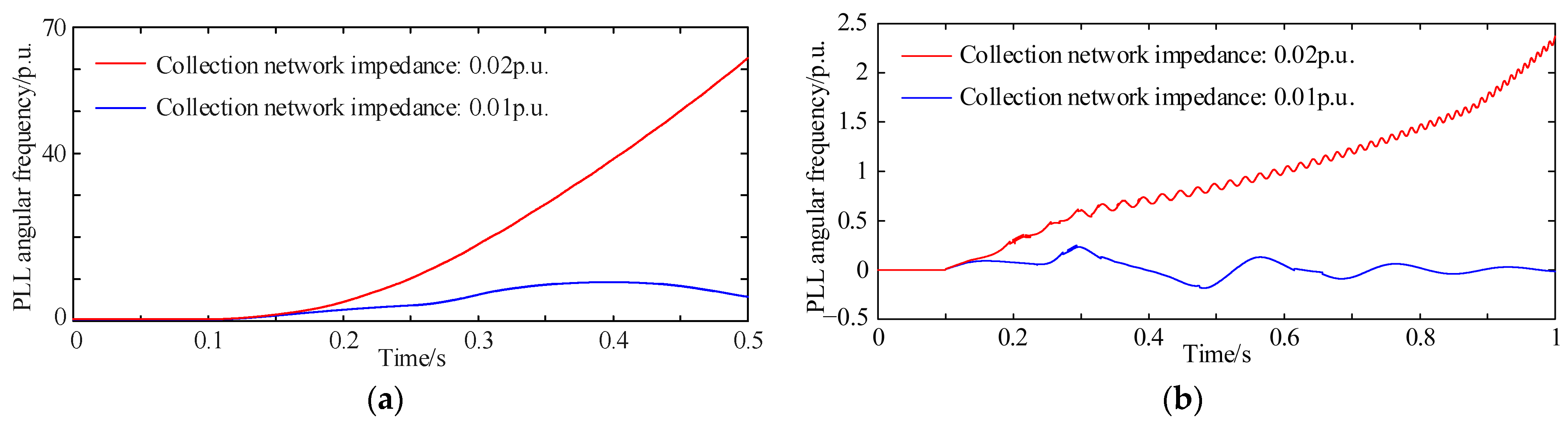

- The collection-line reactance also influences X. From network theory, xcij can be regarded as the mutual reactance between generator i and generator j (i ≠ j) or the self-reactance from generator i to the collection bus (i = j). For a fixed number of generators, depends on the collection network topology and parameters (i, j = 1, 2, …, N). A greater electrical distance between generators and the collection bus, or higher mutual impedance between generators, increases xcij, which raises X and reduces the transient synchronization stability of the wind farm.

4. Case Study

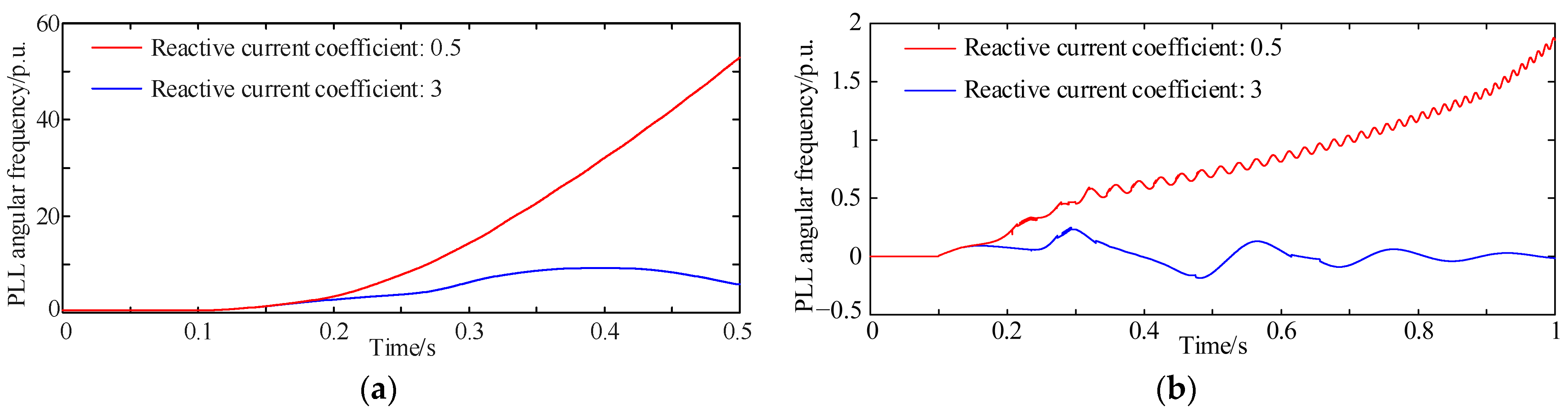

4.1. Impact of Reactive-Current Coefficient on Transient Synchronization Stability

4.2. Impact of Wind-Farm Export-Line Impedance on Transient Synchronization Stability

4.3. Impact of Generator Number on Transient Synchronization Stability

4.4. Impact of Collection Network on Transient Synchronization Stability

5. Conclusions

- A single-machine aggregated model was developed for analyzing transient synchronization stability of a wind farm considering the interactions between multiple generators. Using this model, the equivalent accelerating and decelerating areas of a wind farm were defined, providing key metrics to understand how multi-machine interactions induce transient synchronization instability.

- The mechanism by which multi-PMSG interactions induce transient synchronization instability in a wind farm is analytically revealed, by analyzing the effects of the generator dynamics, number of generators, network topology, and system parameters on the equivalent accelerating and decelerating areas.

- A smaller low-voltage ride-through reactive-current coefficient increases the equivalent accelerating area during a fault. Likewise, a higher steady-state active power output enlarges the accelerating area during the fault and reduces the decelerating area after fault clearance, adversely affecting transient synchronization stability.

- A larger number of generators, higher export-line impedance, or greater self-impedance to the collection bus and mutual impedance between generators all increase the equivalent accelerating area during a fault and reduce the decelerating area after fault clearance, further degrading transient synchronization stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Control Loop | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Outer loop | (5, 5000) DC voltage outer loop (0.1, 10) Reactive power/voltage outer loop |

| Inner loop | (0.15, 45) d/q-axis current inner loop |

| PLL | (1.5, 5) |

| Low voltage ride through (LVRT) | 0.88 p.u. Activation threshold of the LVRT 1 Reactive power current coefficient |

References

- Mao, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, Z. PLL positive feedback effect suppression and stability analysis of grid-connected inverter under weak grid. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2025, 45, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Guo, P.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Z. Review on control and protection for renewable energy integration through VSC-HVDC. High Volt. Eng. 2020, 46, 1460–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W.; Guo, L. Overview of transient stability analysis of phase locked loop synchronization in weak-grid connected VSC. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R. Nonlinear Modeling and Transient Synchronous Stability Analysis of PLL-Based VSC Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Lin, Z.; Xiahou, K.; Wu, Q.H. Constructing an energy function for power systems with DFIGWT generation based on a synchronous-generator-mimicking model. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cai, X. Transient grid- synchronization stability analysis of grid-tied voltage source converters: Stability region estimation and stabilization control. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 7871–7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Du, W.; Zhao, T.; Xie, H.; Wang, H..; Yi, S. Transient synchronization stability analysis of a grid-connected wind farm with multiple PMSGs. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6934–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Song, X.; Sheng, W.; Gao, F.; Liu, J. Analysis method and control strategy for transient synchronous stability of grid- connected new energy resources system considering current dynamics during LVRT. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 4556–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Wu, F.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, T. Transient synchronizing stability margin assessment of phase-locked synchronous inverter based on potential energy boundary surface. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 50, 4802–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, J.; Kurths, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhan, M. Generalized swing equation and transient synchronous stability with PLL-based VSC. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taul, M.G.; Wang, X.; Davari, P.; Blaabjerg, F. An overview of assessment methods for synchronization stability of grid-connected converters under severe symmetrical grid faults. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 9655–9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yao, J.; Zhong, Q.; Gong, S.; Hao, X. Transient synchronization stability analysis of hybrid power system with grid-following and grid-forming renewable energy generation units. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 8378–8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. A constant damping phase-locked loop for enhancing transient stability of grid-following inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z. Control strategy of transient synchronization stability of full-scale wind turbines during grid faults. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 5935–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zha, X.; Li, X.; Huang, M.; Sun, J. An improved equal area criterion for transient stability analysis of converter-based microgrid considering nonlinear damping effect. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 11272–11284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Tian, Z.; Huang, M.; Sun, P.; Zha, X.; Hu, P. A conservatism improved transient stability analysis of grid-following converters based on the proposed elliptic-equal area criterion. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Huang, W.; Shen, C.; Lun, Y.; Shuai, Z. Transient synchronization stability analysis of paralleled converter systems with phase-locked loop. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 6338–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, B.; Xu, S.; Yu, L.; Wang, B.; Li, W. Definition, classification, and analysis method of the strength of power system integrated with high penetration of power electronics. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 7039–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zang, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C. Transient synchronization stability of grid-tied multi-VSCs system considering nonlinear damping and transient interactions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 16775–16791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Cha, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. Synchronization stability analysis of grid-connected inverter based on improved equal area criterion. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Mou, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Hui, J.; Du, Z. Transient synchronization stability analysis of multi-virtual-synchronous-gene-rator system considering controller limiting. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 49, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Du, W.; Wang, H. Small-signal stability of a grid-connected PMSG wind farm dominated by dynamics of PLLs under weak grid connection. Trans. China Electrochnical Soc. 2021, 36, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yao, W.; Wen, J.; Fang, J.; Jiang, L.; He, H.; Cheng, S. Impact of power grid strength and PLL parameters on stability of grid-connected DFIG wind farm. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Su, T.; Bu, H.; Dong, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, X. Small-signal equivalent modeling method for multiple distributed renewable energy clusters. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 49, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Du, W.; Wang, H. Dynamic equivalent model of a grid-connected wind farm for oscillation stability analysis. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Du, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, H. An approximate aggregated impedance model of a grid-connected wind farm for the study of small-signal stability. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 3847–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, B.; Wang, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.; Li, Q. Analysis on the Transient Synchronization Stability of a Wind Farm with Multiple PLL-Based PMSGs. Processes 2026, 14, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020321

Ren B, Wang D, Zhu X, Zhang N, Chen C, Li Q. Analysis on the Transient Synchronization Stability of a Wind Farm with Multiple PLL-Based PMSGs. Processes. 2026; 14(2):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020321

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Bixing, Dajiang Wang, Xinyao Zhu, Ningyu Zhang, Chunyu Chen, and Qiang Li. 2026. "Analysis on the Transient Synchronization Stability of a Wind Farm with Multiple PLL-Based PMSGs" Processes 14, no. 2: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020321

APA StyleRen, B., Wang, D., Zhu, X., Zhang, N., Chen, C., & Li, Q. (2026). Analysis on the Transient Synchronization Stability of a Wind Farm with Multiple PLL-Based PMSGs. Processes, 14(2), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020321