Integrated PSA Hydrogen Purification, Amine CO2 Capture, and Underground Storage: Mass–Energy Balance and Cost Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reference Plant Definition

2.2. Unit Operation Models and Governing Equations

2.2.1. Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA)

2.2.2. Amine-Based CO2 Capture (30 wt% MEA)

2.2.3. Multi-Stage Compression

2.2.4. Primary Energy Penalty Calculation

2.3. Process Integration Measures

2.4. Geological Storage Site Selection Criteria

2.5. Techno-Economic Assessment

- Natural gas: 4 USD/MMBtu;

- Electricity: 50 USD/MWh;

- CO2 transport and storage fee: 15 USD/t;

- Total CAPEX: 1350 USD/(kg/h) capacity.

2.6. Process Flow Diagram and Validation

3. Results and Discussion

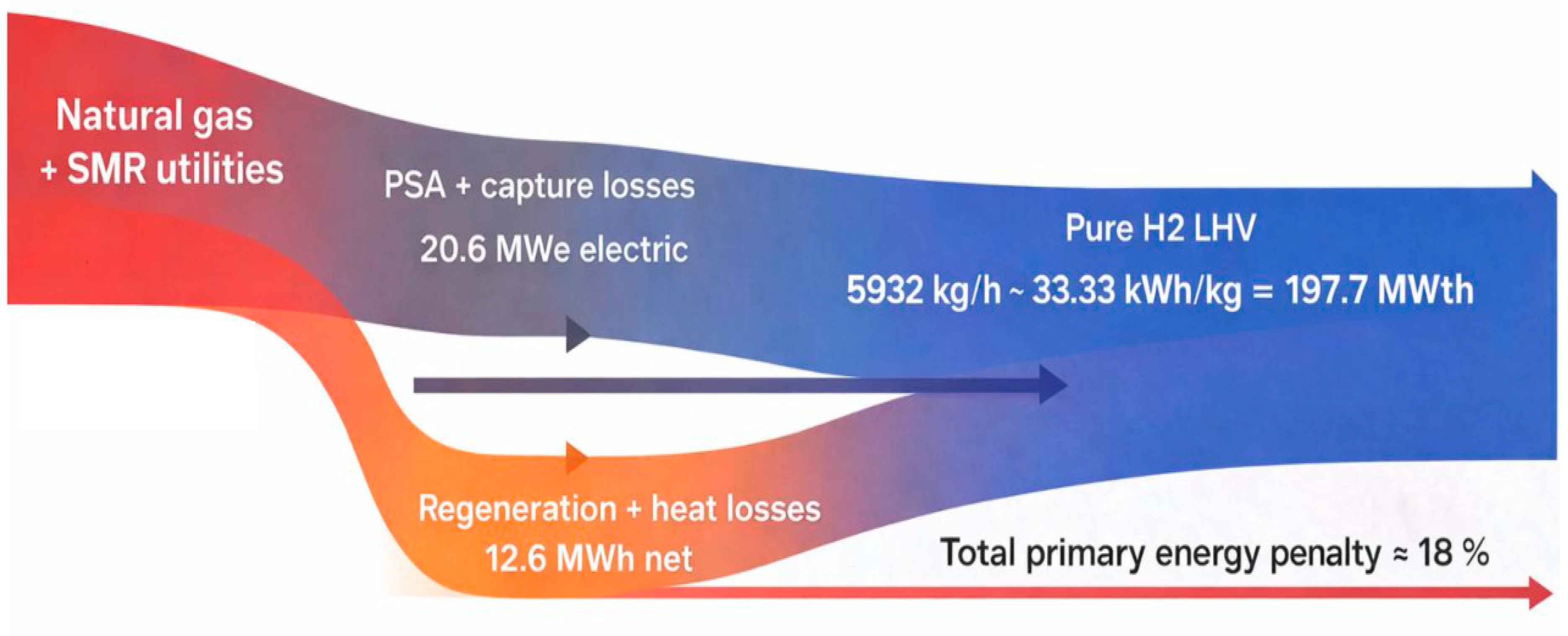

3.1. Mass and Energy Balances

3.2. Energy Performance and Integration Benefits

3.3. Techno-Economic Results

Capital Investment Considerations

3.4. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

3.5. Geological Feasibility and Safety

3.6. Comparison with the Literature and Implications

3.7. Generalizability and Transferability of Results

4. Conclusions

- ≥90% CO2 capture, corresponding to 832 t/d of permanently sequestered CO2;

- A primary energy penalty reduced to 18% of hydrogen LHV, corresponding to an absolute primary energy saving of 8–12 MW through heat and pressure integration;

- A levelized hydrogen production cost of 0.94–1.06 USD/kg H2 (base case 0.98 USD/kg), highly competitive with current and projected low-carbon hydrogen pathways.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSA | Pressure Swing Adsorption |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| N2 | Nitrogen |

| MEA | Monoethanolamine |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| UHS | Underground Storage of Hydrogen |

| CAPEX | Capital Expense |

| OPEX | Operating Expense |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost Of Hydrogen |

| CRF | Capital Recovery Factor |

| WGS | Water–Gas Shift |

References

- Dinçer, İ.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, C.; Dinçer, İ. Comparative assessment of hydrogen production methods from renewable and non-renewable sources. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekir, U. Experimental Study on Microwave-Assisted Non-Thermal Plasma Technology for Industrial-Scale SO2 and Fly Ash Control in Coal-Fired Flue Gas. Process 2025, 13, 3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, C.; Adlen, E.; Beddington, J.; Carter, E.A.; Fuss, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Minx, J.C.; Smith, P.; Williams, C.K. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Dowell, N.; Fennell, P.S.; Shah, N.; Maitland, G.C. The role of CO2 capture and utilization in mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentou, H.; Hoque, B.; Abdalla, M.A.; Saber, A.F.; Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Aliyu, M.; Alkhedhair, A.M.; Alabduly, A.J.; Abdelnaby, M.M. Recent advances and challenges in solid sorbents for CO2 capture. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekir, U. Design and experimental study of a novel microwave-assisted burner based on plasma combustion for pulverized coal applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroneos, C.; Dompros, A.; Roumbas, G.; Moussiopoulos, N. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen fuel production processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2004, 29, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.X.; Yao, R.; Wu, Y.H.; Qui, J.S. Progress and prospects of hydrogen production: Opportunities and challenges. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luberti, M.; Ahn, H. Review of polybed pressure swing adsorption for hydrogen purification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10911–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, V.; Voigt, J.; Jordan, C.; Harasek, M. Hydrogen purification by pressure swing adsorption: High-pressure PSA performance in recovery from seasonal storage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, S. Pressure swing adsorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 6, 1389–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R. Underground hydrogen storage: Characteristics and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotogino, F.; Donadei, S.; Bünger, U.; Landinger, H. Large scale hydrogen underground storage for securing future energy supplies. In Proceedings of the 18th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Essen, Germany, 16–21 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordache, M.; Schitea, D.; Deveci, M.; Akyurt, İ.Z.; Iordache, I. An integrated ARAS and interval type-2 hesitant fuzzy sets method for underground site selection: Seasonal hydrogen storage in salt caverns. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 175, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, O.; Al-khuzaei, M.; Al-Shafi, M.; Bicer, Y.; Abushaikha, A.S. Blue hydrogen production from natural gas reservoirs: A review of application and feasibility. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 70, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhai, H.; Holubnyak, E. Technological evolution of large-scale blue hydrogen production toward the U.S. Hydrogen Energy Earthshot. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B. Towards underground hydrogen storage: A review of barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematpur, H.; Abdollahi, R.; Rostami, S.; Haghighi, M.; Blunt, M.J. Review of underground hydrogen storage: Concepts and challenges. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 7, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, Y.; Yasemi, S.; Abdi, M.; Ghasemi Ertian, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Bagheri, M. A Review of Integrated Carbon Capture and Hydrogen Storage: AI-Driven Optimization for Efficiency and Scalability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachu, S. CO2 storage in geological media: Role, means, status and barriers to deployment. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, P.S.; Meckel, T.A. Maturing global CO2 storage resources on offshore continental margins to achieve 2DS emissions reductions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, D.; Fennell, P.; Shah, N.; Petit, C.; Dowell, N.M. A techno-economic analysis and systematic review of carbon capture and storage (CCS) applied to the iron and steel, cement, oil refining and pulp and paper industries. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 6297–6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaseri, A.; Yekeen, N.; Al-Mukainah, H.; Hassanpouryouzband, A. Geochemical interactions in geological hydrogen storage: The role of sandstone clay content. Fuel 2024, 361, 130728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot-Handford, M.E.; Abanades, J.C.; Anthony, E.J.; Blunt, M.J.; Brandani, S.; Mac Dowell, N.; Fernandez, J.R.; Ferrari, M.C.; Gross, R.; Hallett, J.P.; et al. Carbon capture and storage update. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 130–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Adjiman, C.S.; Bardow, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Boston, A.; Brown, S.; Fennell, P.S.; Fuss, S.; Galindo, A.; Hackett, L.A.; et al. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): The way forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1062–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, N.S.; Haq, B.; Shehri, D.A.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Zaman, E. A review on underground hydrogen storage: Insight into geological sites, influencing factors and future outlook. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 461–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Taiwo, K.; Ndulue, U.F.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Oni, B.A. A review of underground hydrogen storage systems: Current status, modeling approaches, challenges, and future prospective. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 80, 449–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, A.S.; Kobos, P.H.; Borns, D.J. Geologic storage of hydrogen: Scaling up to meet city transportation demands. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 15570–15582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. A review of underground fuel storage events and putting risk into perspective with other areas of the energy supply chain. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2009, 313, 173–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P.J.; Faulkner, D.R.; Worden, R.H.; Aplin, A.C.; Butcher, A.R.; Iliffe, J. Experimental measurement of, and controls permeability and permeability anisotropy of caprocks from the CO2 storage project at the Krechba Field, Algeria. J. Geogr. Res. 2011, 116, B12208. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, N.; Alcalde, J.; Miocic, J.M.; Hangx, S.J.T.; Kallmeyer, J.; Ostertag-Henning, C.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Thaysen, E.M.; Strobel, G.J.; Schmidt Hattenberger, C.; et al. Enabling large-scale hydrogen storage in porous media—The scientific challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlayan, D.G.; Weber, N.; Heinrichs, H.U.; Linssen, J.; Robinius, M.; Kukla, P.A.; Stolten, D. Technical potential of salt caverns for hydrogen storage in Europe. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 6793–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, A.; Mignard, D.; Wilkinson, M. Seasonal storage of hydrogen in a depleted natural gas reservoir. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5549–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysyy, M.; Ferno, M.A.; Ersland, G. Effect of relative permeability hysteresis on reservoir simulation of underground hydrogen storage in an offshore aquifer. J. Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivar, D.; Kumar, S.; Foroozesh, J. Underground hydrogen storage: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 45, 6793–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine scrubbing for CO2 capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEAGHG. Low-Carbon Hydrogen from Natural Gas: Global Roadmap; IEAGHG Technical Report 2022-07; IEAGHG: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Pei, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, H. Development status and prospect of salt cavern energy storage technology. Earth Energy Sci. 2025, 1, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, N.; Booth, M.G.; Haszeldine, R.S.; Wilkinson, M.; Scafidi, J.; Edlmann, K. Hydrogen storage in porous geological formations-onshore play opportunities in the midland valley (Scotland, UK). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 20861–20874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopffel, N.; Jansen, S.; Gerritse, J. Microbial side effects of underground hydrogen storage—Knowledge gaps, risks and opportunities for successful implementation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8594–8606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaysen, E.M.; Armitage, T.; Slabon, L.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Edlmann, K. Microbial risk assessment for underground hydrogen storage in porous rocks. Fuel 2023, 352, 128852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.G. Measurement of hydrogen diffusion in brine at high pressures and elevated temperatures: Implications for underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 139, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL). Comparison of Commercial, State-of-the-Art, Fossil-Based Hydrogen Production Technologies; NETL Report; U.S. Department of Energy: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL). Assessment of Hydrogen Production with CO2 Capture: Baseline State-of-the-Art Plants; NETL Report; U.S. Department of Energy: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2024; International Energy Agency IEA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BloombergNEF. Hydrogen Production Costs Outlook: Blue and Low-Carbon Hydrogen Pathways; Bloomberg Finance, L.P.: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Clean Hydrogen; Hydrogen Shot Program Report Update 2024; Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (DOE): Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Mole Fraction (%) | Flow Rate (kmol/h) |

|---|---|---|

| H2 | 75.5 | 3370 |

| CO2 | 18.8 | 839 |

| CH4 | 3.9 | 174 |

| CO + N2 + Ar | 1.8 | 80 |

| Total | 100.0 | 4463 |

| Parameter | Unit | H2 Salt Cavern | H2-Depleted Field/Aquifer | CO2 Saline Aquifer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir permeability ‘k’ | mD | <0.1 | 10–500 | 50–1000 | [28,29] |

| Darcy velocity limit | m/s | <10−8 | <10−7 | <10−6 | [30] |

| Caprock permeability | m2 | <10−20 | <10−19 | <10−20 | [31,32] |

| Minimum depth | m | >500 | >800 | >800 | [33,34] |

| Expected leakage (1000 y) | % of stored | <0.001 | <0.1 | <0.01 | [35,36,37] |

| Stream | Flow (kmol/h) | Mass Flow (t/h) | Pressure (bar) | Temperature (°C) | Duty (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shifted syngas to PSA | 4463 | - | 30 | 40 | - |

| Pure H2 product (post-PSA) | 2966 | 5.93 | 30 | 40 | - |

| H2 delivered to storage | 2966 | 5.93 | 200 | 40 | 9.2 (compression) |

| PSA tail gas | 1127 | - | 1.2 | 40 | - |

| Captured CO2 | 755 | 33.2 | 150 | 40 | 3.1 (compression) |

| Regeneration steam (gross) | - | - | 4 | 143 | 18 |

| Recovered heat (lean amine) | - | - | - | 120 → 60 | 5.4 |

| Net regeneration steam | - | - | 4 | 143 | 12.6 |

| Component | CAPEX Contribution ((USD/(kg/h)) | Specific Cost (USD/kg H2) |

|---|---|---|

| PSA purification | 350 | 0.12 |

| Amine CO2 capture (90%) | 650 | 0.50 |

| CO2 transport + storage | 200 | 0.15 |

| H2 compression + UHS | 300 | 0.23 |

| Integration credits and contingencies | −150 | −0.02 |

| Total (base case) | 1350 | 0.98 |

| Range (different geology) | 1250–1550 | 0.94–1.06 |

| Study/Source | Year | Configuration | CO2 Capture Rate (%) | LCOH (USD/kg H2) | Keynotes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work (triple- integrated) | 2025 | SMR + PSA + MEA CCS + UHS with synergies | ≥90 | 0.94–1.06 (base 0.98) | Full triple integration, heat/pressure synergies | - |

| NETL baseline | 2023–2024 | SMR + PSA+ CCS (no UHS) | ~90–95 | 1.8–2.5 | Standalone CCS, higher energy penalty | [45,46] |

| IEAGHG merchant SMR + CCS | 2024 | SMR + CCS (standalone) | 90–95 | 2.0–3.0 | No UHS, partial integration | [39,47] |

| DOE Liftoff/ BloombergNEF | 2024–2025 | Various SMR/ATR + CCS | 90+ | 2.0–3.5 | No full triple UHS integration | [48] |

| Recent reviews (avg. blue H2) | 2023–2025 | SMR + CCS variants | 85–95 | 2.0–3.5 | Higher gas prices in some cases | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Üresin, E. Integrated PSA Hydrogen Purification, Amine CO2 Capture, and Underground Storage: Mass–Energy Balance and Cost Analysis. Processes 2026, 14, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020319

Üresin E. Integrated PSA Hydrogen Purification, Amine CO2 Capture, and Underground Storage: Mass–Energy Balance and Cost Analysis. Processes. 2026; 14(2):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020319

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜresin, Ersin. 2026. "Integrated PSA Hydrogen Purification, Amine CO2 Capture, and Underground Storage: Mass–Energy Balance and Cost Analysis" Processes 14, no. 2: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020319

APA StyleÜresin, E. (2026). Integrated PSA Hydrogen Purification, Amine CO2 Capture, and Underground Storage: Mass–Energy Balance and Cost Analysis. Processes, 14(2), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020319