Intelligent Disassembly System for PCB Components Integrating Multimodal Large Language Model and Multi-Agent Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We have proposed a novel intelligent PCB disassembly system, exploring the systemic feasibility of using robotic arms to achieve the entire process of waste PCB recycling, including identification and disassembly to recycling and storage.

- Addressing the challenges of lacking flexibility and intelligent decision-making in existing rule-based robotic disassembly systems for waste PCBs, we proposed a solution that utilizes multimodal large models for intelligent perception of circuit boards and employs multi-agent systems to achieve flexible decision-making for the multi-stage disassembly process.

- Experimental results demonstrate that our proposed system can achieve efficient identification of components such as chips and diodes, with a recovery rate of up to 80% for various types of components.

2. Related Works

2.1. Traditional Disassembly Methods

2.1.1. Thermal Disassembly Technology

2.1.2. Mechanical Separation Technology

2.1.3. Chemical Treatment Technology

2.2. Robotic Disassembly Fundamentals

2.2.1. Control Methods in Robotics

2.2.2. Recent Advances and Persistent Challenges

3. Materials and Methods

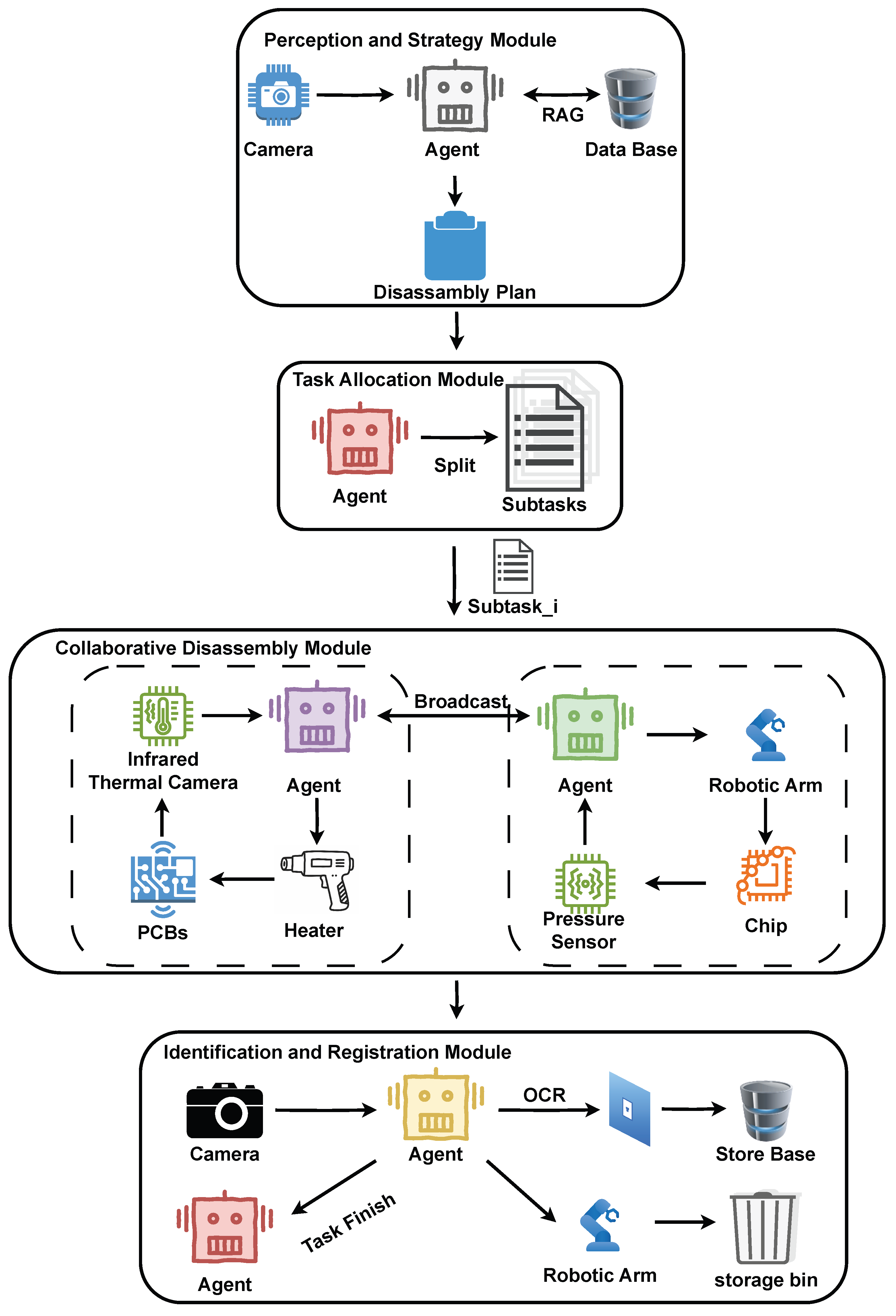

3.1. The Role of Multi-Agent and Multi-Modal in Waste Printed Circuit Board Disassembly

3.2. Perception and Strategy Module

3.3. Task Allocation Module

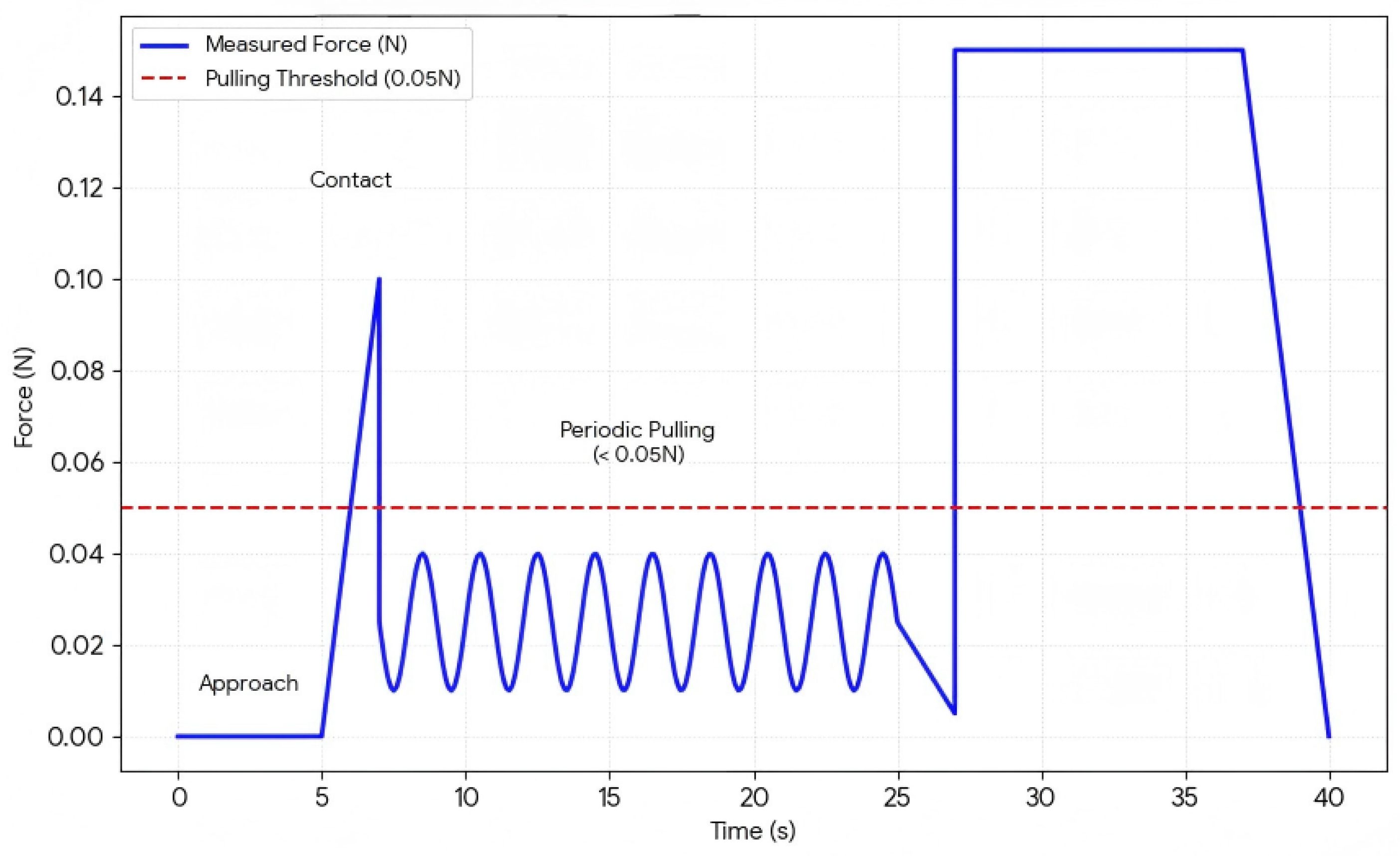

3.4. Collaborative Disassembly Module

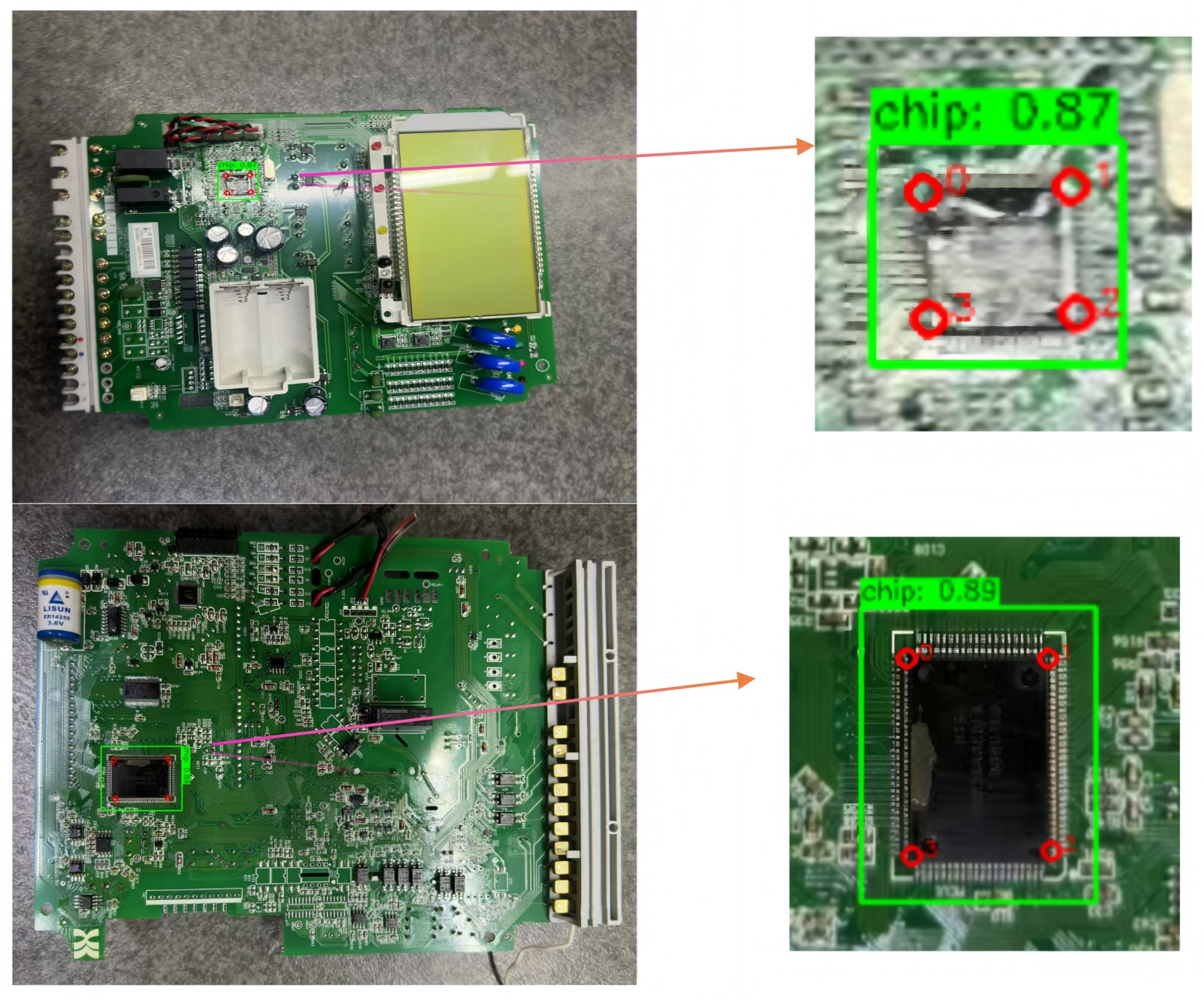

3.4.1. Identification and Registration Module

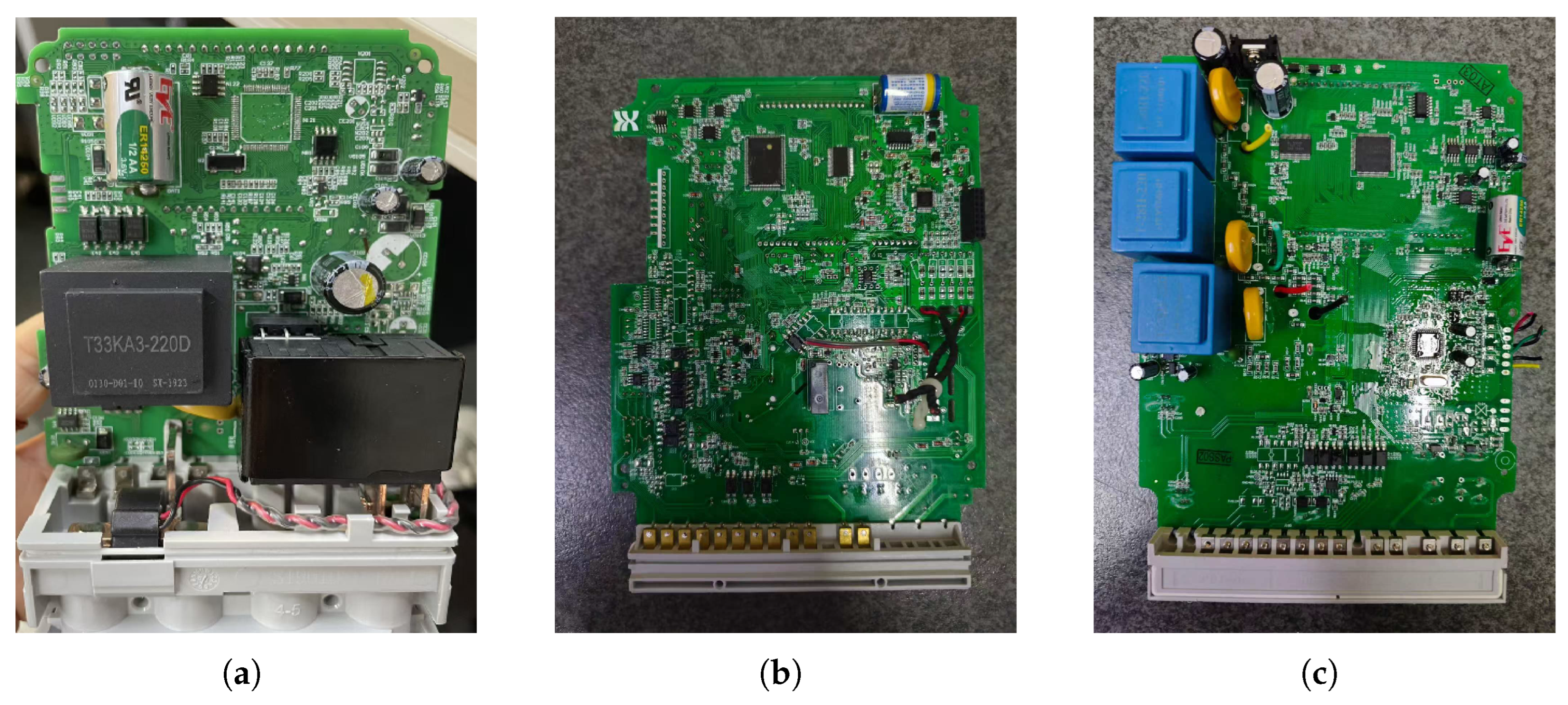

3.4.2. Experimental Setup

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adenuga, A.A.; Amos, O.D.; Olajide, O.D.; Eludoyin, A.O.; Idowu, O.O. Environmental impact and health risk assessment of potentially toxic metals emanating from different anthropogenic activities related to E-wastes. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Digital Economy Report 2024: Shaping an Environmentally Sustainable and Inclusive Digital Future; Technical Report UNCTAD/DER/2024; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Neto, J.F.; Monteiro, M.; Silva, M.M.; Miranda, R.; Santos, S.M. Household practices regarding e-waste management: A case study from Brazil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbasir, S.M.; Hassan, S.S.; Kamel, A.H.; El-Nasr, R.S. Status of electronic waste recycling techniques: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 16533–16547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunali, M.; Tunali, M.M.; Yenigun, O. Characterization of different types of electronic waste: Heavy metal, precious metal and rare earth element content by comparing different digestıon methods. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 23, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudali, U.K.; Patil, M.; Saravanabhavan, R.; Saraswat, V. Review on e-waste recycling: Part I—A prospective urban mining opportunity and challenges. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2021, 6, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Kumar, S. Evaluation of e-waste status, management strategies, and legislations. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 6957–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle-Demessie, E.; Mezgebe, B.; Dietrich, J.; Shan, Y.; Harmon, S.; Lee, C.C. Material recovery from electronic waste using pyrolysis: Emissions measurements and risk assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopacek, B. Intelligent Disassembly of components from printed circuit boards to enable re-use and more efficient recovery of critical metals. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, A.A.; Dinh, K.N.; Charpentier, N.M.; Brambilla, A.; Gabriel, J.C.P. Dismantling of Printed Circuit Boards Enabling Electronic Components Sorting and Their Subsequent Treatment Open Improved Elemental Sustainability Opportunities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Marques, L.; Neto, P. A robotic system to automate the disassembly of pcb components. In Proceedings of the Iberian Robotics Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 456–465. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzo, W.A.; Figueiredo, R.A.; De Andrade, V.F. Characterization of Printed Circuit Boards for Metal and Energy Recovery after Milling and Mechanical Separation. Materials 2014, 7, 4555–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilchap, F.; Mousavi, S.M. Structural study and metal speciation assessments of waste PCBs and environmental implications: Outlooks for choosing efficient recycling routes. Waste Manag. 2022, 151, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Huang, Y.; Li, G.; He, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C. Pollution profiles and health risk assessment of VOCs emitted during e-waste dismantling processes associated with different dismantling methods. Environ. Int. 2014, 73, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Bi, X.; Huang, B.; Liu, M.; Sheng, G.; Fu, J. Hydroxylated PBDEs and brominated phenolic compounds in particulate matters emitted during recycling of waste printed circuit boards in a typical e-waste workshop of South China. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 177, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Neto, J.F.; Silva, M.M.; Machado Santos, S. A mini-review of E-waste management in Brazil: Perspectives and challenges. CLEAN-Air Water 2019, 47, 1900152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasopoulos, D.; Mendrinou, P.; Oustadakis, P.; Kousi, P.; Stergiou, A.; Karamoutsos, S.D.; Hatzikioseyian, A.; Tsakiridis, P.E.; Remoundaki, E.; Agatzini-Leonardou, S. Hydrometallurgical recovery of silver and gold from waste printed circuit boards and treatment of the wastewater in a biofilm reactor: An integrated pilot application. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Duan, C.; Lu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Fan, X.; Wen, P.; Ju, Y. Improvement of the crushing effect of waste printed circuit boards by co-heating swelling with organic solvent. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Xie, H.; Liu, L. A novel dismantling process of waste printed circuit boards using water-soluble ionic liquid. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Ghosh, M.; Parhi, P.; Mukherjee, P.; Mishra, B. Waste printed circuit boards recycling: An extensive assessment of current status. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Pan, J.; Liu, Z.; Song, S.; Liu, G. Study on disassembling approaches of electronic components mounted on PCBs. In Advances in Life Cycle Engineering for Sustainable Manufacturing Businesses, Proceedings of the 14th CIRP Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, 11–13 June 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Mu, T. Comprehensive investigation on the thermal stability of 66 ionic liquids by thermogravimetric analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 8651–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.Y.; Zhou, M. A new technology for recycling solder from waste printed circuit boards using ionic liquid. Waste Manag. Res. 2012, 30, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Hou, K.; Li, J.; Zhu, X. Examining the technology acceptance for dismantling of waste printed circuit boards in light of recycling and environmental concerns. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.; Han, Y.; Park, J. Apparatus for electronic component disassembly from printed circuit board assembly in e-wastes. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2015, 144, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qiu, K. A new technology for recycling materials from waste printed circuit boards. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Guo, Z. High-temperature centrifugal separation of Cu from waste printed circuit boards. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Yamazaki, N.; Jiang, W. Characterization and inventory of PCDD/Fs and PBDD/Fs emissions from the incineration of waste printed circuit board. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6322–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Xu, Z. An environmentally friendly technology of disassembling electronic components from waste printed circuit boards. Waste Manag. 2016, 53, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tan, Q.; Liu, L.; Dong, Q.; Li, J. Recycling tin from electronic waste: A problem that needs more attention. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9586–9598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeșan, H.; Tiuc, A.E.; Purcar, M. Advanced recovery techniques for waste materials from IT and telecommunication equipment printed circuit boards. Sustainability 2019, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.F.C.; Leão, V.A. The role of sodium chloride on surface properties of chalcopyrite leached with ferric sulphate. Hydrometallurgy 2007, 87, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinkaya, P.; Liipo, J.; Kolehmainen, E.; Haapalainen, M.; Leikola, M.; Lundström, M. Leaching of trace amounts of metals from flotation tailings in cupric chloride solutions. Mining, Metall. Explor. 2019, 36, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Gong, D.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Qi, J.; Song, S. Compliant Force Control for Robots: A Survey. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, N.; Neto, P.; Pires, J.N.; Loureiro, A. An optimal fuzzy-PI force/motion controller to increase industrial robot autonomy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 68, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calanca, A.; Muradore, R.; Fiorini, P. A Review of Algorithms for Compliant Control of Stiff and Fixed-Compliance Robots. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2016, 21, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadun, A.; Jalani, J.; Sukor, J. An overview of active compliance control for a robotic hand. FME Trans. 2016, 11, 11872–11876. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Pham, D.; Wang, Y.W.; Ji, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z. A strategy for human-robot collaboration in taking products apart for remanufacture. FME Trans. 2019, 47, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Pham, D.T.; Ji, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H. Design of a compliant device for peg-hole separation in robotic disassembly. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 124, 3011–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, G.; Santochi, M.; Dini, G.; Tracht, K.; Scholz-Reiter, B.; Fleischer, J.; Kristoffer Lien, T.; Seliger, G.; Reinhart, G.; Franke, J.; et al. Grasping devices and methods in automated production processes. CIRP Ann. 2014, 63, 679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, S.; Fontana, G.; Basile, V.; Valori, M.; Fassi, I. Micro-robotic Handling Solutions for PCB (re-)Manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, R.; Ambrosch, R.; Bergmann, K.; Britten, S.; Brumm, H.; Chmielarz, A.; Connemann, S.; Eschen, M.; Frank, A.; Fricke-Begemann, C.; et al. Next generation urban mining-Automated disassembly, separation and recovery of valuable materials from electronic equipment: Overview of R&D approaches and first results of the European project ADIR. In Proceedings of the EMC, ADIR, Zrenjnin, Serbia, 16–17 June 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Jin, Z.; Gu, R.; Qu, H. Automatic disassembly and recovery device for mobile phone circuit board CPU based on machine vision. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1684, 012137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Feng, P. Detection Method of End-of-Life Mobile Phone Components Based on Image Processing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ding, G.; Du, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.; Baek, J.; Cho, S.; Hwang, S.J.; Park, J. Adaptive-RAG: Learning to Adapt Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models through Question Complexity. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14403. [Google Scholar]

- DeepMind, G. Gemini API Documentation. Technical Report, Google. 2024. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Mohsin, M.; Rovetta, S.; Masulli, F.; Cabri, A. Automated Disassembly of Waste Printed Circuit Boards: The Role of Edge Computing and IoT. Computers 2025, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Type | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated circuit (IC) | Composite | An integrated circuit (IC) is fabricated on a semiconductor substrate, typically silicon, which is doped with impurities to form p-n junctions. These components are interconnected via metallic pathways, usually made from alloys. The packaging material may consist of plastic or ceramic. |

| Aluminum Capacitor (AC) | Composite | This component comprises an aluminum foil and an aluminum oxide coating, along with a liquid or gel electrolyte. These distinct materials are physically combined to enable its function. |

| Tantalum Capacitor (TC) | Composite | It is composed of tantalum powder and an electrolyte. The tantalum powder forms a porous structure with a large surface area, coated with an oxide layer that acts as a dielectric; this structure is physically integrated with the electrolyte. |

| Diode | Alloy/Composite | It is constructed from semiconductor materials, such as silicon or germanium, which are doped with impurities and feature metal contacts that may be alloys. The use of doped semiconductors and metallic connections is essential to its function. |

| Transistor | Alloy/Composite | Like diodes, transistors are manufactured from semiconductor materials doped with impurities and equipped with metal (alloy) contacts. These materials physically influence the flow of electrons. |

| Resistor | Composite | This component can be produced using a carbon film, metal film, or metal oxide film coated onto an insulating substrate. The body and leads employ various materials, which are physically connected to form the resistive device. |

| Inductor | Composite | An inductor consists of a copper coil wound around a magnetic core, which may be air, ferrite, or an iron alloy. The coil and core are physically separate but interact magnetically. |

| Component | Recognition Rate (%) | Capture Rate (%) | Melting Rate (%) | Average Time Consumption (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC | 100 | 80 | 100 | 168.5 |

| AC | 100 | 70 | 100 | 112.3 |

| TC | 93.3 | 36.6 | 100 | 109.6 |

| Diode | 96.7 | 46.7 | 100 | 98.1 |

| Transistor | 100 | 66.7 | 100 | 100.4 |

| Resistor | 90.0 | 56.7 | 100 | 106.7 |

| Inductor | 93.3 | 70 | 100 | 124.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Ouyang, L.; Weng, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, K. Intelligent Disassembly System for PCB Components Integrating Multimodal Large Language Model and Multi-Agent Framework. Processes 2026, 14, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020227

Wang L, Ouyang L, Weng H, Chen X, Wang A, Zhang K. Intelligent Disassembly System for PCB Components Integrating Multimodal Large Language Model and Multi-Agent Framework. Processes. 2026; 14(2):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020227

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, Liu Ouyang, Huiying Weng, Xiang Chen, Anna Wang, and Kexin Zhang. 2026. "Intelligent Disassembly System for PCB Components Integrating Multimodal Large Language Model and Multi-Agent Framework" Processes 14, no. 2: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020227

APA StyleWang, L., Ouyang, L., Weng, H., Chen, X., Wang, A., & Zhang, K. (2026). Intelligent Disassembly System for PCB Components Integrating Multimodal Large Language Model and Multi-Agent Framework. Processes, 14(2), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020227