Enrichment of Wheat Flour Bread with Pleurotus ostreatus Lyophilizate and Aqueous Extract—Influence on Dough and Bread Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. The Preparation of P. ostreatus Lyophilizate and Hot Water Extract

2.3. Dough and Bread Preparation

2.4. Dough Rheology

2.5. Chemical Characterization

2.6. Specific Volume and Height of Bread

2.7. Crumb Texture Analysis

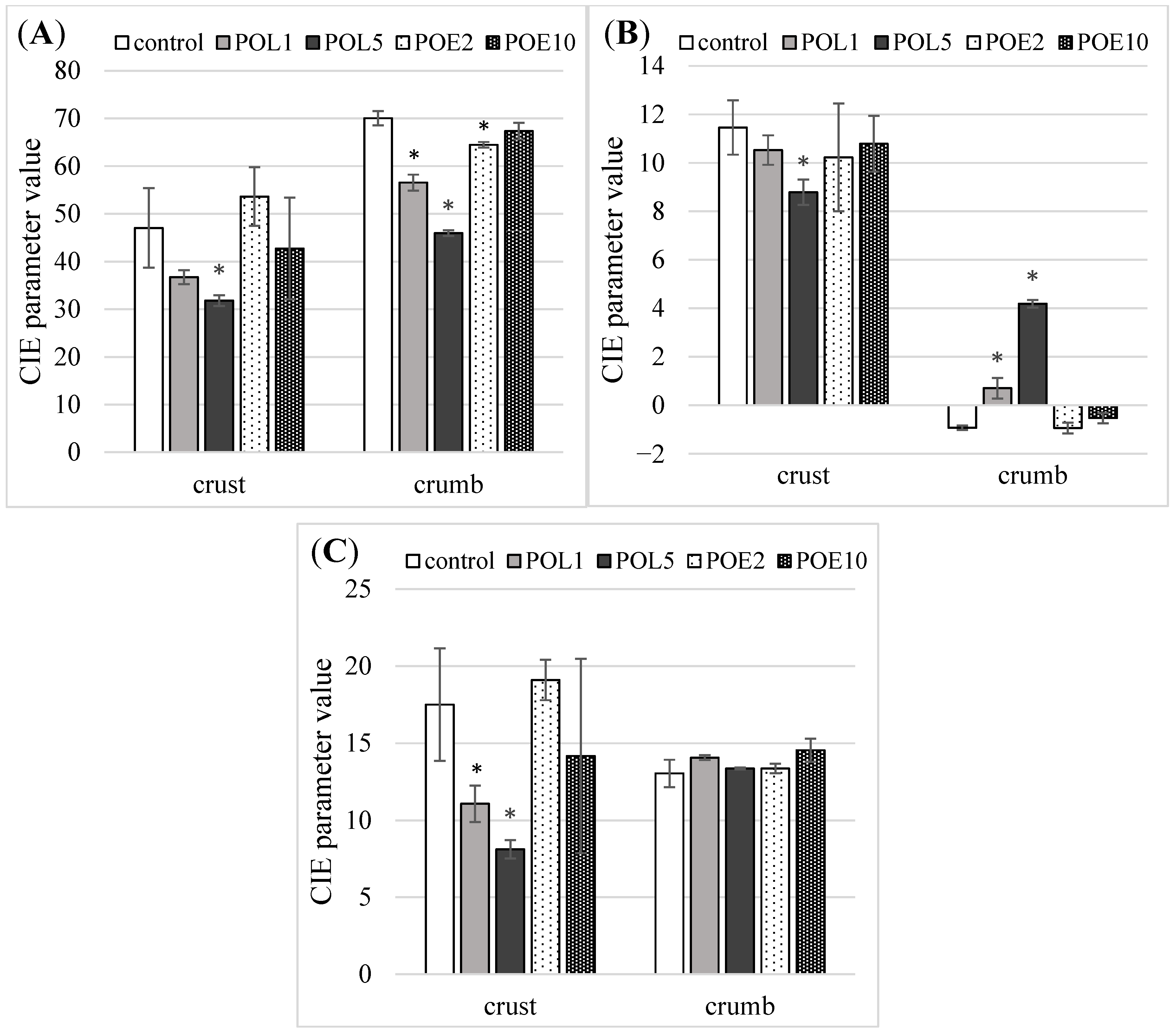

2.8. Crumb and Crust Color

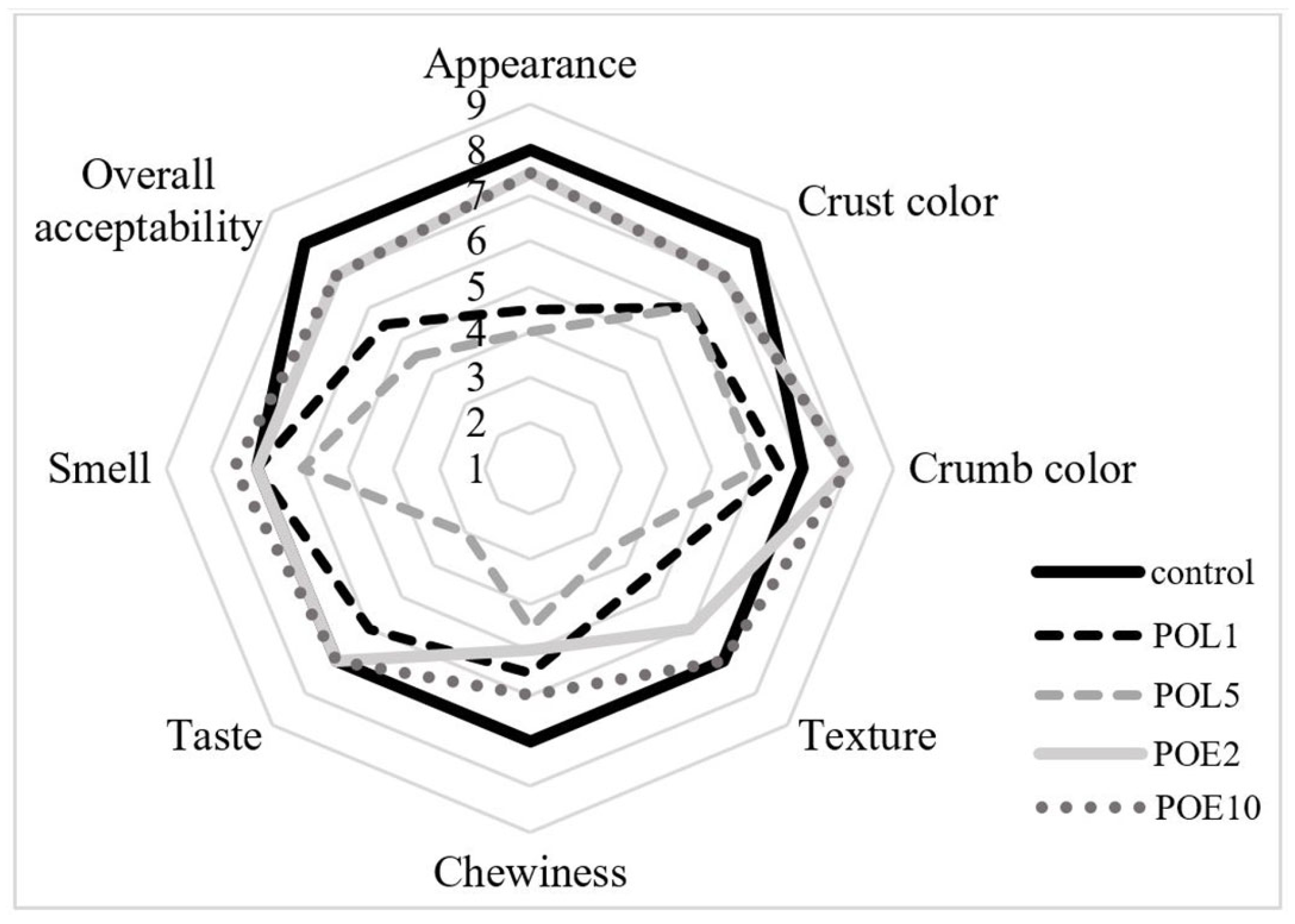

2.9. Sensory Analysis

2.10. Antioxidant Capacity of Bread

2.11. Statistical Analysis of Results

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition of Raw Materials

3.2. Impact of P. ostreatus Lyophilizate and Extract on Dough Properties

3.3. Bread Quality Alterations Induced by P. ostreatus Lyophilizate and Extract

3.4. Nutritional and Bioactive Contribution of P. ostreatus Lyophilizate and Extract to Bread Quality

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Losoya-Sifuentes, C.; Simões, L.S.; Cruz, M.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Loredo-Treviño, A.; Teixeira, J.A.; Nobre, C.; Belmares, R. Development and characterization of Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom–wheat bread. Starch-Stärke 2021, 74, 2100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Attri, B.L.; Kamal, S.; Pathera, A.K.; Kashyap, R.; Verma, S.; Sharma, V.P. Nutritional enhancement, microstructural modifications, and sensory evaluation of mushroom-enriched multigrain bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 9523–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławińska, A.; Sołowiej, B.G.; Radzki, W.; Fornal, E. Wheat Bread Supplemented with Agaricus bisporus Powder: Effect on Bioactive Substances Content and Technological Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Brennan, M.A.; Guan, W.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L.; Brennan, C.S. Enhancing the Nutritional Properties of Bread by Incorporating Mushroom Bioactive Compounds: The Manipulation of the Predictive Glycaemic Response and the Phenolic Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Brennan, M.A.; Serventi, L.; Brennan, C.S. Incorporation of Mushroom Powder into Bread Dough—Effects on Dough Rheology and Bread Properties. Cereal Chem. 2018, 95, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzee, T.J.; Cao, L.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, R. Fungi for Future Foods. J. Future Foods 2021, 1, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effiong, M.E.; Umeokwochi, C.P.; Afolabi, I.S.; Chinedu, S.N. Assessing the nutritional quality of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom). Front. Nutr. 2024, 10, 1279208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effiong, M.E.; Umeokwochi, C.P.; Afolabi, I.S.; Chinedu, S.N. Comparative antioxidant activity and phytochemical content of five extracts of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Cui, L.; Ma, C. Extraction and Bioactivities of the Chemical Composition from Pleurotus ostreatus: A Review. J. Future Foods 2024, 4, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, R.; Singh, J.; Dash, K.K.; Dar, A.H. Comparative Study of Freeze Drying and Cabinet Drying of Button Mushroom. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Pandiselvam, R.; Su, D.; Xu, H. Comparative Analysis of Drying Methods on Pleurotus eryngii: Impact on Drying Efficiency, Nutritional Quality, and Flavor Profile. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 4598–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahorec, J.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Petrović, J.; Nikolić, I.; Pavlić, B.; Bijelić, K.; Bojanić, N.; Fišteš, A. Fortification of bread with carob extract: A comprehensive study on dough behavior and product quality. Foods 2025, 14, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, T.B.; Marçal, S.; Vale, P.; Sousa, A.S.; Nunes, J.; Pintado, M. Exploring the Bioactive Potential of Mushroom Aqueous Extracts: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Prebiotic Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Simarro, P.; Gómez-Gómez, L.; Rubio-Moraga, Á.; Moreno-Giménez, E.; López-Jiménez, A.; Prieto, A.; Ahrazem, O. Valorization of Mushroom By-Products for Sustainability: Exploring Antioxidant and Prebiotic Properties. J. Food Biochem. 2025, 2025, 3527311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbian Official Methods. Određivanje fizičkih osobina pšeničnog brašna Brabenderovim farinografom. In Pravilnik o Metodama Fizičkih i Hemijskih Analiza za Kontrolu Kvaliteta Žita, Mlinskih i Pekarskih Proizvoda, Testenina i Brzo Smrznutih Testa (Regulation of Methods of Physical and Chemical Analysis for Quality Control of Grain, Milling and Bakery Products, Pasta and Quick Frozen Dough); Službeni List SFRJ 74/88; Government of SFRJ: Belgrade, Serbia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dapčević Hadnađev, T.; Pojić, M.; Hadnađev, M.; Torbica, A. The role of empirical rheology on flour quality control. In Wide Spectra of Quality Control; Akyar, I., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 335–360. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists International, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Communities: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gafta Method 10.1:2018; Sugar—Luff Schoorl Method. GAFTA Analysis Methods. The Grain and Feed Trade Association: London, UK, 2018.

- AACC International. AACCI Method 10-05 Baking Quality Methods: Guidelines for Measurement of Volume by Rapeseed Displacement. In Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AACC Method 74-09; Approved Methods of the AACC. American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000.

- CIE. International Commission on Illumination, Colorimetry: Official Recommendation of the International Commission on Illumination; Publication CIE No. (E-1.31); Bureau Central de la CIE: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8586:2012; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO 5492:2008; Sensory Analysis—Vocabulary. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 4121:2003; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Evaluation of Food Products by Sensory Experts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- ISO 8589:2007; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Design of Test Rooms. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Yu, L.; Nanguet, A.-L.; Beta, T. Comparison of Antioxidant Properties of Refined and Whole Wheat Flour and Bread. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Fatima, K.; Saeed, R. Analysis of Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents, and the Anti-Oxidative Potential and Lipid Peroxidation Inhibitory Activity of Methanolic Extract of Carissa opaca Roots and Its Fractions in Different Solvents. Antioxidants 2014, 3, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pickard, M.D.; Beta, T. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity and Electronic Taste and Aroma Properties of Antho-Beers from Purple Wheat Grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8958–8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power Assay: Direct Measure of Total Antioxidant Activity of Biological Fluids and Modified Version for Simultaneous Measurement of Total Antioxidant Power and Ascorbic Acid Concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotti, F.; Turchiuli, C.; Lavelli, V. Production of Stable Emulsions Using β-Glucans Extracted from Pleurotus ostreatus to Encapsulate Oxidizable Compounds. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Witkowska, A.M. Evaluation of Polish Wild Mushrooms as Beta-Glucan Sources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Bassart, Z.; Fabra, M.J.; Torres, J.A.; Chiralt, A. Compositional Differences of β-Glucan-Rich Extracts from Three Relevant Mushrooms Obtained through a Sequential Extraction Protocol. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.; Sood, M.; Bandral, J.D. Impact of Different Drying Methods on Proximate and Mineral Composition of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus florida). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2020, 19, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajad, S.; Singh, J.; Gupta, N.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, V.; Shankar, U. Physico-Chemical, Color Profile, and Total Phenol Content of Freeze-Dried (Oyster Mushroom) Pleurotus ostreatus. Pharma Innov. 2023, 12, 2076–2078. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, M.; Khan, M.U.; Owaid, M.N.; Khan, M.R.; Shariati, M.A.; Igor, P.; Ntsefong, G.N. Development of oyster mushroom powder and its effects on physicochemical and rheological properties of bakery products. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2017, 6, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, K.B.; Nsiah-Asante, R.; Antwi, R.T.; Obirikorang, K.A.; Anokye, R.; Ansong, M. Influence of the Chemical Composition of Sawdust on the Levels of Important Macronutrients and Ash Composition in Pearl Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkanah, F.A.; Oke, M.A.; Adebayo, E.A. Substrate Composition Effect on the Nutritional Quality of Pleurotus ostreatus (MK751847) Fruiting Body. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, A.K.; Pradhan, P.; Chatterjee, S.; Roy, T.; Paul, S.; Saha, R.; Sarkar, J.; Acharya, K. Comparative structural and proximate values of five different cultivated strains of Pleurotus ostreatus. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2013, 6, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Drężek, J.; Możejko-Ciesielska, J. Production of β-Glucans by Pleurotus ostreatus: Cultivation and Genetic Background. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törős, G.; Béni, Á.; Peles, F.; Gulyás, G.; Prokisch, J. Comparative Analysis of Freeze-Dried Pleurotus ostreatus Mushroom Powders on Probiotic and Harmful Bacteria and Its Bioactive Compounds. J. Fungi 2024, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ruan, C.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, J. Mixolab behavior, quality attributes and antioxidant capacity of breads incorporated with Agaricus bisporus. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3921–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, G.-H.; Song, G.-S.; Kim, Y.-S. Effect of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) powder on bread quality. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2005, 10, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Kardooni, Z.; Ebrahimi, M.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. The Role of Water Alternatives in Bread Formulation and Its Quality: An Emerging Source of Sustainable and Cost-Effective Bakery Improvers. Future Foods 2025, 12, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Vázquez, A.; Tomasini, A.; Armas-Tizapantzi, A.; Marcial-Quino, J.; Montiel-González, A.M. Extracellular proteases and laccases produced by Pleurotus ostreatus PoB: The effects of proteases on laccase activity. Int. Microbiol. 2022, 25, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, G.; Bianco, C.; Cennamo, G.; Giardina, P.; Marino, G.; Monti, M.; Sannia, G. Purification, characterization, and functional role of a novel extracellular protease from Pleurotus ostreatus. App. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2754–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, J.P.; Kelly, B.J.; Davis, H.; Hahn, A.D. Methods for Lowering Gluten Content Using Fungal Cultures. Patent Publication No. 20210274818, 9 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejević, N.; Polović, N.; Milošević, J. Kinetics of Protease Thermal Inactivation. In Zymography; Khalil, R.A., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Wahab, N.B.; Darus, N.A.; Mohd Daud, S.A. Incorporation of mushroom powder in bread. In Proceedings of the National Technology Research in Engineering, Design and Social Science Conference (nTrends’22), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 5–6 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Zhao, L.; Yang, W.; MClements, D.J.; Hu, Q. Enrichment of bread with nutraceutical-rich mushrooms: Impact of Auricularia auricular (mushroom) flour upon quality attributes of wheat dough and bread. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabotic, J.; Trcek, T.; Popovic, T.; Brzin, J. Basidiomycetes harbour a hidden treasure of proteolytic diversity. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 128, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępniewska, S.; Salamon, A.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Piecyk, M.; Kowalska, H. The Impact of Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) on the Baking Quality of Rye Flour and Nutrition Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Rye Bread. Foods 2025, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L404, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

| Analyte (g/100 g) 1 | Wheat Flour | POL 2 | POE 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 12.75 ± 0.09 | 11.01 ± 0.21 | n.d. 4 |

| Fat | 1.11 ± 0.00 | 1.66 ± 0.00 | n.d. |

| Ash | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 7.47 ± 0.00 | n.d. |

| Protein | 7.67 ± 0.00 | 26.19 ± 0.00 | n.d. |

| Total carbohydrates | 77.90 ± 0.00 | 53.67 ± 0.00 | n.d. |

| Total sugars | 7.20 ± 0.00 | 11.00 ± 0.00 | 7.50 ± 0.99 |

| Total dietary fibers | 1.30 ± 0.00 | 32.64 ± 0.00 | n.d. |

| β-glucans | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 24.63 ± 0.80 | 9.23 ± 0.86 |

| Parameter | Control | POL1 2 | POL5 | POE2 | POE10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farinographic data | |||||

| Water absorption (%) 1 | 53.30 ± 0.23 a | 53.56 ± 0.17 a | 54.43 ± 0.25 b | 53.67 ± 0.20 a | 53.57 ± 0.13 a |

| Dough development (min) | 2.25 ± 0.05 c | 1.75 ± 0.00 a | 2.00 ± 0.05 b | 2.00 ± 0.00 b | 1.75 ± 0.10 a |

| Dough stability (min) | 0.25 ± 0.02 a | 0.50 ± 0.03 b | 0.25 ± 0.05 a | 0.50 ± 0.05 b | 0.25 ± 0.00 a |

| Degree of softening (FU) | 60 ± 2.50 a | 275 ± 3.00 c | 290 ± 3.25 d | 60 ± 1.63 a | 80 ± 2.34 b |

| Extensographic data | |||||

| Resistance (EU) | 465 ± 7.5 a | n.d. 3 | n.d. | 450 ± 5.0 a | 470 ± 22.5 a |

| Extensibility (mm) | 140 ± 2.0 a | n.d. | n.d. | 150 ± 6.5 b | 140 ± 4.5 ab |

| Energy (cm2) | 86.0 ± 3.3 a | n.d. | n.d. | 86.0 ± 1.2 a | 83.1 ± 2.1 a |

| Resistance/Extensibility | 3.3 ± 0.1 a | n.d. | n.d. | 3.0 ± 0.2 a | 3.4 ± 0.2 a |

| Sample 1 | Moisture (g/100 g) | Hardness (N) | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Resilience | Chewiness (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 32.40 ± 3.26 a | 11.39 ± 1.74 d | 0.99 ± 0.00 a | 0.63 ± 0.04 a | 0.30 ± 0.04 a | 7.21 ± 2.82 ab |

| POL1 | 25.38 ± 0.16 c | 20.17 ± 5.79 b | 0.89 ± 0.01 b | 0.35 ± 0.05 b | 0.16 ± 0.02 b | 8.29 ± 3.75 ab |

| POL5 | 23.06 ± 3.03 c | 46.82 ± 2.01 a | 0.88 ± 0.03 b | 0.33 ± 0.04 b | 0.15 ± 0.02 b | 13.60 ± 0.72 a |

| POE2 | 30.25 ± 2.84 a | 17.14 ± 1.51 c | 0.98 ± 0.02 a | 0.58 ± 0.01 a | 0.28 ± 0.01 a | 9.81 ± 1.01 ab |

| POE10 | 28.64 ± 0.37 ab | 12.44 ± 0.97 d | 0.96 ± 0.03 a | 0.58 ± 0.02 a | 0.26 ± 0.03 a | 6.90 ± 2.75 b |

| Sample 1 | Protein (g/100 g) | TDF 2 (g/100 g) | TPC 3 (mg GAE/100 g) | TFC 4 (mg QE/100 g) | FRAP 5 (μM Fe2+/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 10.08 ± 0.18 b | 1.37 ± 0.11 a | 81.47 ± 2.81 e | 40.26 ± 4.31 b | 58.54 ± 4.28 d |

| POL1 | 8.94 ± 0.22 a | 1.42 ± 0.19 a | 143.62 ± 6.18 b | 32.59 ± 11.24 b | 136.03 ± 13.42 b |

| POL5 | 10.17 ± 0.05 b | 4.91 ± 0.24 c | 352.50 ± 11.72 a | 74.47 ± 12.14 a | 423.57 ± 24.16 a |

| POE2 | 9.03 ± 0.08 a | 2.26 ± 0.13 b | 91.38 ± 2.48 d | 32.71 ± 10.42 b | 91.29 ± 9.86 c |

| POE10 | 9.00 ± 0.14 a | 1.00 ± 0.26 a | 115.83 ± 11.82 c | 40.48 ± 6.48 b | 142.70 ± 15.38 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zahorec, J.; Šoronja-Simović, D.; Petrović, J.; Smole Možina, S.; Klančnik, A.; Sabotič, J.; Sterniša, M. Enrichment of Wheat Flour Bread with Pleurotus ostreatus Lyophilizate and Aqueous Extract—Influence on Dough and Bread Quality. Processes 2026, 14, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010065

Zahorec J, Šoronja-Simović D, Petrović J, Smole Možina S, Klančnik A, Sabotič J, Sterniša M. Enrichment of Wheat Flour Bread with Pleurotus ostreatus Lyophilizate and Aqueous Extract—Influence on Dough and Bread Quality. Processes. 2026; 14(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleZahorec, Jana, Dragana Šoronja-Simović, Jovana Petrović, Sonja Smole Možina, Anja Klančnik, Jerica Sabotič, and Meta Sterniša. 2026. "Enrichment of Wheat Flour Bread with Pleurotus ostreatus Lyophilizate and Aqueous Extract—Influence on Dough and Bread Quality" Processes 14, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010065

APA StyleZahorec, J., Šoronja-Simović, D., Petrović, J., Smole Možina, S., Klančnik, A., Sabotič, J., & Sterniša, M. (2026). Enrichment of Wheat Flour Bread with Pleurotus ostreatus Lyophilizate and Aqueous Extract—Influence on Dough and Bread Quality. Processes, 14(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010065