Modelling the Behaviour of Pollutant Indicators in Activated Carbon Adsorption of Oil and Textile Effluents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

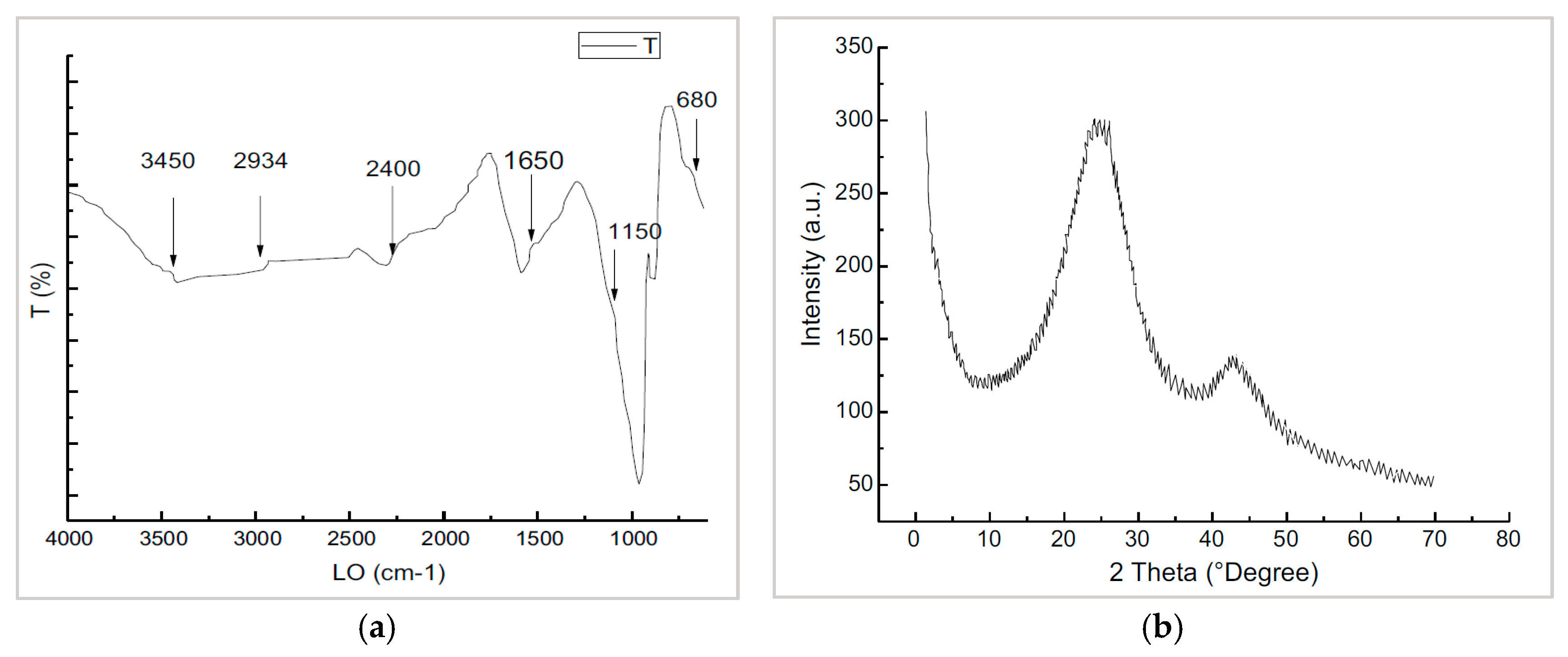

2.1. Adsorbent

2.2. Numerical Model

2.2.1. Simulation Parameters

2.2.2. Mathematical Models

Mass Conservation

Energy Conservation

2.2.3. Assumptions

2.2.4. Spatial and Temporal Discretisation of the Model Domains

2.2.5. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temperature Behaviour in the Treatment of Oil and Textile Effluents

3.2. Oil Effluent

3.2.1. Model Input Parameters: Diffusion Coefficients

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Constituents of the Oil Effluent

3.2.3. Breakthrough Curves of the Oil Effluent

3.3. Textile Effluent

3.3.1. Mass Transfer Coefficient Input Data

3.3.2. Spatial Distribution of Constituents of the Textile Effluent

3.3.3. Breakthrough Curves of the Textile Effluent

3.3.4. Optimisation of the Adsorption in the Textile Adsorption Column

3.4. Sensitivity Study of Temperature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cross-sectional area of the packed bed (m2) | |

| ci | bulk concentration of species i in the fluid phase (mol m−3) |

| equilibrium concentration of species i in the fluid phase (mol m−3) | |

| specific heat capacity of the adsorbed species i or solid phase (J kg−1K−1) | |

| specific heat capacity of the liquid phase (J kg−1 K−1) | |

| Dei | effective axial dispersion coefficient of species i in the packed bed (m2 s−1) |

| Deff | effective diffusivity of species i within the solid or porous phase (m2 s−1) |

| Dmi | molecular diffusivity of species i in the fluid phase (m2 s−1) |

| DSO | limiting or intrinsic surface diffusivity of species i at infinite dilution (m2 s−1) |

| K | Boltzmann constant (1.3806 × 10−23 J K−1) |

| effective axial thermal conductivity of the packed bed (W m−1 K−1) | |

| kLDF | linear driving force mass transfer coefficient (s−1) |

| equilibrium adsorbed concentration of species i on the solid phase (mol kg−1 of solid) | |

| qi | instantaneous adsorbed concentration of species i (mol kg−1 of solid) |

| volume-averaged adsorbed concentration within the particle (mol kg−1 of solid) | |

| ri | hydrodynamic radius of species i (m) |

| rp | radius of the adsorbent particle (m) |

| absolute temperature (K) | |

| t | time (s) |

| temperature difference relative to the reference temperature, (K) | |

| U | superficial fluid velocity (m s−1) |

| Vv | void (interstitial) volume of the adsorption column (m3) |

| z | axial coordinate along the column height (m) |

| ε | bed porosity (-) |

| Shi | Sherwood number for species i (-) |

| εp | intraparticle porosity of the adsorbent (-) |

| particle density of the adsorbent (kg m−3) | |

| dynamic viscosity of the fluid (Pa s) | |

| density of the liquid phase (kg m−3) | |

| heat of adsorption of species i evaluated at reference temperature (J mol−1) | |

| density of the adsorbed phase or solid associated with species i (kg m−3) |

References

- Castillo-Suárez, L.A.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.G.; Linares-Hernández, I.; Martínez-Miranda, V.; Teutli-Sequeira, E.A. A critical review of textile industry wastewater: Green technologies for the removal of indigo dyes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. IJEST 2023, 20, 10553–10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thombre, N.; Patil, P.; Yadav, A.; Patwardhan, A. A short review on water management and reuse in textile industry—A sustainable approach. Discov. Water 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhazraji, H.; Alatabe, M.J.A. Coagulation/flocculation process for oily wastewater treatment. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 25, 3–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyena, A.P.; Sam, K. A review of the threat of oil exploitation to mangrove ecosystem: Insights from Niger Delta, Nigeria. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Shah, G.; Singhal, K.; Soni, V. Comprehensive insights into the impact of oil pollution on the environment. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 74, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Verma, Y. Biochemical toxicity of benzene. J. Environ. Biol. 2005, 26, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Khan, H. Short Review: Benzene’s toxicity: A consolidated short review of human and animal studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2007, 26, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, B.; Sabumon, P.C. A comprehensive review on biodegradation of azo dye mixtures, metabolite profiling with health implications and removal strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, D.; Melidis, P.; Aivasidis, A.; Gimouhopoulos, K. Degradation of azo-reactive dyes by ultraviolet radiation in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Dye. Pigment. 2002, 52, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berez, A.; Schäfer, G.; Ayari, F.; Trabelsi-Ayadi, M. Adsorptive removal of azo dyes from aqueous solutions by natural bentonite under static and dynamic flow conditions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, D.; Sharma, M. Impact of Textile Dyes on Human Health and Environment; Jiwaji University: Gwalior, India, 2020; pp. 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meryem, K.; Chemini, R.; Salem, Z.; Khodja, M.; Zeriri, D. Parametric Study of COD Reduction from Textile Processing Wastewater Using Adsorption on Cypress Cone-Based Activated Carbon: An Analysis of a Doehlert Response Surface Design. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 10079–10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Recent advances for dyes removal using novel adsorbents: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Singh, R. Low-Cost RSAC and Adsorption Characteristics in the Removal of Copper Ions from Wastewater. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchou, F.; Hicham, Z.; Hanane, A.; El Gaayda, J.; Akbour, R.; Hamdani, M. Removal of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) from Water and Wastewater by Adsorption and Electrocoagulation Process. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız Töre, G.; Meric, S.; Lofrano, G.; De Feo, G. Removal of Trace Pollutants from Wastewater in Constructed Wetlands. In Emerging Compounds Removal from Wastewater: Natural and Solar Based Treatments; Lofrano, G., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongwiwanna, D.; Tangsathitkulchai, C. The Use of High Surface Area Mesoporous-Activated Carbon from Longan Seed Biomass for Increasing Capacity and Kinetics of Methylene Blue Adsorption from Aqueous Solution. Molecules 2021, 26, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, K.; Shezad, N.; Shafiq, I.; Akhter, P.; Akhtar, F.; Jamil, F.; Shafique, S.; Park, Y.-K.; Hussain, M. A review on activated carbon modifications for the treatment of wastewater containing anionic dyes. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallawar, G.A.; Bhanvase, B.A. A review on existing and emerging approaches for textile wastewater treatments: Challenges and future perspectives. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 1748–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloum, A.; Adegoke, K.A.; Ighalo, J.O.; Conradie, J.; Ohoro, C.R.; Amaku, J.F.; Oyedotun, K.O.; Maxakato, N.W.; Akpomie, K.G.; Okeke, E.S.; et al. Computational methods for adsorption study in wastewater treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simo, M.; Brown, C.J.; Hlavacek, V. Simulation of pressure swing adsorption in fuel ethanol production process. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2008, 32, 1635–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Saha, B.B.; Koyama, S.; Maeda, S.; Maruyama, T. Corrected adsorption rate model of activated carbon–ethanol pair by means of CFD simulation. Int. J. Refrig. 2016, 71, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Saha, B.B.; Koyama, S.; Maeda, S.; Maruyama, T. CFD simulation and experimental validation of ethanol adsorption onto activated carbon packed heat exchanger. Int. J. Refrig. 2017, 74, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, T.; Storti, G.; Rota, R. Detailed simulation of dual-reflux pressure swing adsorption process. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 122, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.G.R.S.; Correia, L.M.S.; de Medeiros, J.L.; Araújo, O.d.Q.F. Natural gas dehydration by molecular sieve in offshore plants: Impact of increasing carbon dioxide content. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 149, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrun, M.H.V.; Bono, A.; Othman, N.; Zaini, M.A.A. Numerical modelling and simulation of methane enrichment: A systematic review on pressure swing adsorption technology. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2024, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cai, J.-g.; Pan, B.-c. Mathematically modeling fixed-bed adsorption in aqueous systems. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2013, 14, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonavičienė, T.; Ciegis, R.; Baltrėnaitė-Gedienė, E.; Chemerys, V. Numerical analysis of liquid-solid adsorption model. Math. Model. Anal. 2019, 24, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Narciso, S.; Lozano-Álvarez, J.A.; Salinas-Gutiérrez, R.; Castañeda-Leyva, N. A Stochastic Model for Adsorption Kinetics. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2021, 5522581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. A comprehensive model of adsorption of resorcinol in rotating packed bed: Theoretical, isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloum, A.; Akpotu, S.O.; Adegoke, K.A.; Okeke, E.S.; Omotola, E.O.; Ohoro, C.R.; Amaku, J.F.; Conradie, J.; Olisah, C.; Akpomie, K.G. Advances in molecular simulations of dye adsorption from wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 439, 128732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadani, M. Adsorption process modeling to reduce COD by activated carbon for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencheikh, I.; Azoulay, K.; Samghouli, N.; Mabrouki, J.; Bouhachlaf, L.; Moufti, A.; El Hajjaji, S. Mathematical and Statistical Study for the Wastewater Adsorbent Regeneration Using the Central Composite Design. In IoT and Smart Devices for Sustainable Environment; Azrour, M., Irshad, A., Chaganti, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukriti; Sharma, J.; Pruthi, V.; Anand, P.; Singh Chaddha, A.P.; Bhatia, J.; Kaith, B.S. Surface response methodology–central composite design screening for the fabrication of a Gx-psy-g-polyacrylicacid adsorbent and sequestration of auramine-O dye from a textile effluent. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 74300–74313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Makwana, A.; Ahammed, M. The use of response surface methodology for modelling and analysis of water and wastewater treatment processes: A review. Water Sci. Technol. A J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2014, 69, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khellouf, M. Optimization of a Hybrid Process for Treatment of Polluted Water. Application to Hydrocarbons and Colorants. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene, Algiers, Algeria, 2020. Available online: https://dspace.usthb.dz/items/f3a85feb-63c2-4852-bbe5-1fcc644b359d (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Khellouf, M.; Chemini, R.; Salem, Z.; Khodja, M.; Zeriri, D.; Jada, A. A new activated carbon prepared from cypress cones and its application in the COD reduction and colour removal from industrial textile effluent. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7756–7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media; American Elsevier Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Guelli Souza, S.; Peruzzo, L.; Souza, A. Numerical study of the adsorption of dyes from textile effluents. Appl. Math. Model. 2008, 32, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeeyan, M.S.; Daud, W.; Shamiri, A. A review of mathematical modeling of fixed-bed columns for carbon dioxide adsorption. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 961–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavan, Y.; Hosseini, S.H.; Ahmadi, G.; Olazar, M. Mathematical model and Energy Analysis of Ethane Dehydration in a Two-layer Packed Bed Adsorption. Particuology 2018, 47, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, I. On the linear driving force approximation for adsorption cooling applications. Int. J. Refrig. 2011, 34, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-J.; Kim, M.-K.; Lee, D.-G.; Ahn, H.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, C.-H. Heat-exchange pressure swing adsorption process for hydrogen separation. AIChE J. 2008, 54, 2054–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.F.; Richardson, J.F. Gas dispersion in packed beds. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1968, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-H.; Jia, B.; Shan, Z.; Lin, X.; Wang, X. The overall-process dynamic mass transfer research of surfactant at the three-phase emulsions interface. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyam, S.; Patra, S. Innovations and challenges in adsorption-based wastewater remediation: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, O.; Banach, M. Sorption of Ag+ and Cu2+ by Vermiculite in a Fixed-Bed Column: Design, Process Optimization and Dynamics Investigations. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, D.; Pang, S.; Xu, L. Prediction of breakthrough curves for multicomponent adsorption in a fixed-bed column using logistic and Gompertz functions. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmahdi, F.; Semra, S.; Haddad, D.; Mandin, P.; Kolli, M.; Bouhelassa, M. Breakthrough Curves Analysis and Statistical Design of Phenol Adsorption on Activated Carbon. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2018, 42, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csempesz, F.; Csáki, K.F. Conformational changes induced by competitive adsorption in mixed interfacial layers of uncharged polymers. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Iwasawa, Y., Oyama, N., Kunieda, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 132, pp. 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Rwiza, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Mtei, K. Removal of heavy metals from binary and multicomponent adsorption systems using various adsorbents—A systematic review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13052–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Brempong, M.; Essandoh, H.M.K.; Asiedu, N.Y.; Momade, F.Y. Bone Char Adsorption of COD and Colour from Tannery Wastewater: Breakthrough Curve Analysis and Fixed Bed Dynamic Modelling. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 6651094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qodah, Z.; Al-Shannag, M.; Hudaib, B.; Bani-Salameh, W.; Shawaqfeh, A.T.; Assirey, E. Synergy and enhanced performance of combined continuous treatment processes of pre-chemical coagulation (CC), solar-powered electrocoagulation (SAEC), and post-adsorption for Dairy wastewater. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Myshkin, V.; Khan, V.; Poberezhnikov, A.; Baraban, A. Effect of Temperature on the Diffusion and Sorption of Cations in Clay Vermiculite. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 11596–11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Xiao, L.; Luo, S.; Liao, G. Numerical simulation study on the effect of temperature on the restricted diffusion in porous media. Magn. Reson. Lett. 2023, 3, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (kg m−3) | Surface Area (BET) (m2 g−1) | Pore Size (nm) | Pore Volume (cm3g−1) | Porosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 | 379.51 | ≤39 | 0.204 | 0.65 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Height (m) | 0.15 |

| Diameter (m) | 0.1 |

| Flow rate Q (L h−1) | 1.5 |

| Porosity of the adsorption bed ε [-] | 0.44 |

| Cycle time t (min) | 50 |

| Temperature (°C) | 25 |

| Pressure (bar) | 1 |

| Parameters | Oil Effluent | Textile Effluent |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.5 | 10.6 |

| Colour (PtCo unit) | - | 500 |

| COD (mg L−1) | 5650 | 865 |

| Suspended solids (mg L−1) | 1648 | 122 |

| Turbidity (FAU) | 1863 | 234 |

| TOC (mg L−1) | 1229 | 345.5 |

| Cl (mg L−1) | 9 | 1.55 |

| Ca (mg L−1) | 36.07 | 36.1 |

| Fe (mg L−1) | 2.46 | - |

| Mn (mg L−1) | 75.8 | 5.29 |

| Cd (mg L−1) | 4.70 | 11.99 × 1 |

| Cr (mg L−1) | 3.58 × 1 | 1.41 × |

| Cu (mg L−1) | 9.85 × 1 | 1.91 |

| Ni (mg L−1) | 7.50 × 1 | 4.21 |

| Pb (mg L−1) | 4.84 × 1 | -- |

| Zn (mg L−1) | 1.00 × 1 | 8.17 × |

| Fluid density (kg m−3) | 987.17 | 991.26 |

| Dynamic viscosity (Pa s) | 1.79 × 10−3 | 9.83 × 10−4 |

| Parameter | Method | Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Hydrogen ion concentration | pH meter WTW Inlab 735 (WTW, Weilheim, Germany) |

| Conductivity | Electrical conduction electrodes | Conductivity meter HACH HQ40d (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA) |

| COD | Potassium dichromate | Spectrophotometer HACH DR1900 (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA) |

| BOD5 | 5-day incubation at 20 °C | Incubator Oxitop IS 200 WTW (WTW, Weilheim, Germany) |

| Colour | Platinum-cobalt (Pt/Co) | Spectrophotometer HACH DR1900 (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA) |

| Turbidity | Formazine Attenuation Unit (FAU) | Turbidimeter HACH 2100 N (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA) |

| TSS | 45 μm filtration | HACH 45 μm filter (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA) |

| TOC | High-temperature combustion | Skalar Formac HT-I TOC Analyser (Skalar, Breda, The Netherlands) |

| Hydrocarbons | Hexane extraction + GC | GC Clarus 580 PerkinElmer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Heavy metals | Plasma spectrometry | ICP Optima 8000 PerkinElmer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Cations/Anions | Ion chromatography | ICS 5000+ DC Thermo Scientific (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Constituent | Water | TOC | Ca | Cd | Cr | Cu | Fe | COD | Mn | Ni | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bi (L g−1) | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.042 | 0.007 | 0.027 | 0.018 | 0.020 | 1.4 × 1 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.006 |

| bj (L mg−1) | 2.34 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 6.00 | 3.45 | 2.65 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 3.56 | 5.76 | 4.00 |

| Δ (J.mol−1) | −68.26 | −8.28 | −129.65 | −55.68 | −29.57 | −1.23 | −10 | −83.48 | −110.10 | −1.42 | −10 | −42.44 |

| Initial and Boundary Conditions | Mass Transfer | Heat Transfer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0 | C = 0 | q = 0 | T = T0 | |

| t > 0 | z = 0 | C = C0 | q = 0 | T = |

| t > 0 | z = H | |||

| Constituent | TOC | Ca | Cl | Cd | Cr | Cu | Mn | Zn | Ni | Pb | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ri (pm) | 1400 | 180 | 100 | 215 | 128 | 128 | 140 | 138 | 135 | 180 | 140 |

| Dmi (10−6 m2s−1) | 0.87 | 12.56 | 16.04 | 7.86 | 8.71 | 9.03 | 8.71 | 6.10 | 8.96 | 7.72 | 8.71 |

| Ds (10−6 m2s−1) | 1.26 | 12.70 | 11.13 | 6.19 | 6.53 | 6.17 | 7.06 | 3.19 | 5.02 | 5.91 | 6.53 |

| kLDF (10−6 s−1) | 6.67 | 44.35 | 17.8 | 7.92 | 6.90 | 6.71 | 8.48 | 4.16 | 6.06 | 0.25 | 6.18 |

| Parameters | Treated Oil Effluent | Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Simulated | ||

| pH | 12 | 9.05 | 24.6 |

| COD (mg L−1) | 3219 | 2847.03 | 11.5 |

| Turbidity (FAU) | 147 | 146.66 | 0.2 |

| Suspended solids (mg L−1) | 139 | 130.56 | 6.0 |

| Constituent | TOC | Ca | Cl | Cd | Cr | Cu | Mn | Zn | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dmi (109 cm2s−1) | 0.171 | 1.33 | 2.4 | 1.117 | 1.877 | 1.877 | 1.716 | 1.741 | 1.78 |

| Ds (109 cm2s−1) | 0.19 | 2.35 | 4.56 | 1 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 2.91 | 0.28 |

| kLDF (s−1) | 0.47 | 4.41 | 43.3 | 1.54 | 2.67 | 2.36 | 1.41 | 3.17 | 0.87 |

| Parameter | Treated Textile Effluent | Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Simulated | ||

| pH | 12 | 11.34 | 5.49 |

| COD (mg L−1) | 700 | 675.83 | 3.45 |

| Turbidity (FAU) | 77 | 71.38 | 7.29 |

| Suspended Solids SS (mg L−1) | 35 | 37.19 | 6.27 |

| Colour (PtCo Unit) | 98 | 88.68 | 9.50 |

| Operating Key Factors | Symbol | Levels Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | +1 | ||

| Bed height (m) | X1 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| Flow rate Q (L h−1) | X2 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Cycle time (min) | X3 | 20 | 50 | 80 |

| Component | Source | DF | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD | Model | 10 | 17,781.82 | 1778.18 | 9.36 |

| Error | 5 | 948.94 | 189.79 | Prob. > F | |

| Total | 15 | 18,730.76 | - | 0.0117 * | |

| Suspended solids | Model | 10 | 7165.05 | 716.50 | 26.51 |

| Error | 5 | 135.10 | 27.02 | Prob. > F | |

| Total | 15 | 7300.16 | - | 0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rabet, S.; Chemini, R.; Schäfer, G.; Aiouache, F. Modelling the Behaviour of Pollutant Indicators in Activated Carbon Adsorption of Oil and Textile Effluents. Processes 2026, 14, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010063

Rabet S, Chemini R, Schäfer G, Aiouache F. Modelling the Behaviour of Pollutant Indicators in Activated Carbon Adsorption of Oil and Textile Effluents. Processes. 2026; 14(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabet, Samia, Rachida Chemini, Gerhard Schäfer, and Farid Aiouache. 2026. "Modelling the Behaviour of Pollutant Indicators in Activated Carbon Adsorption of Oil and Textile Effluents" Processes 14, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010063

APA StyleRabet, S., Chemini, R., Schäfer, G., & Aiouache, F. (2026). Modelling the Behaviour of Pollutant Indicators in Activated Carbon Adsorption of Oil and Textile Effluents. Processes, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010063