Raw Material Heating and Optical Glass Synthesis Using Microwaves

Abstract

1. Introduction

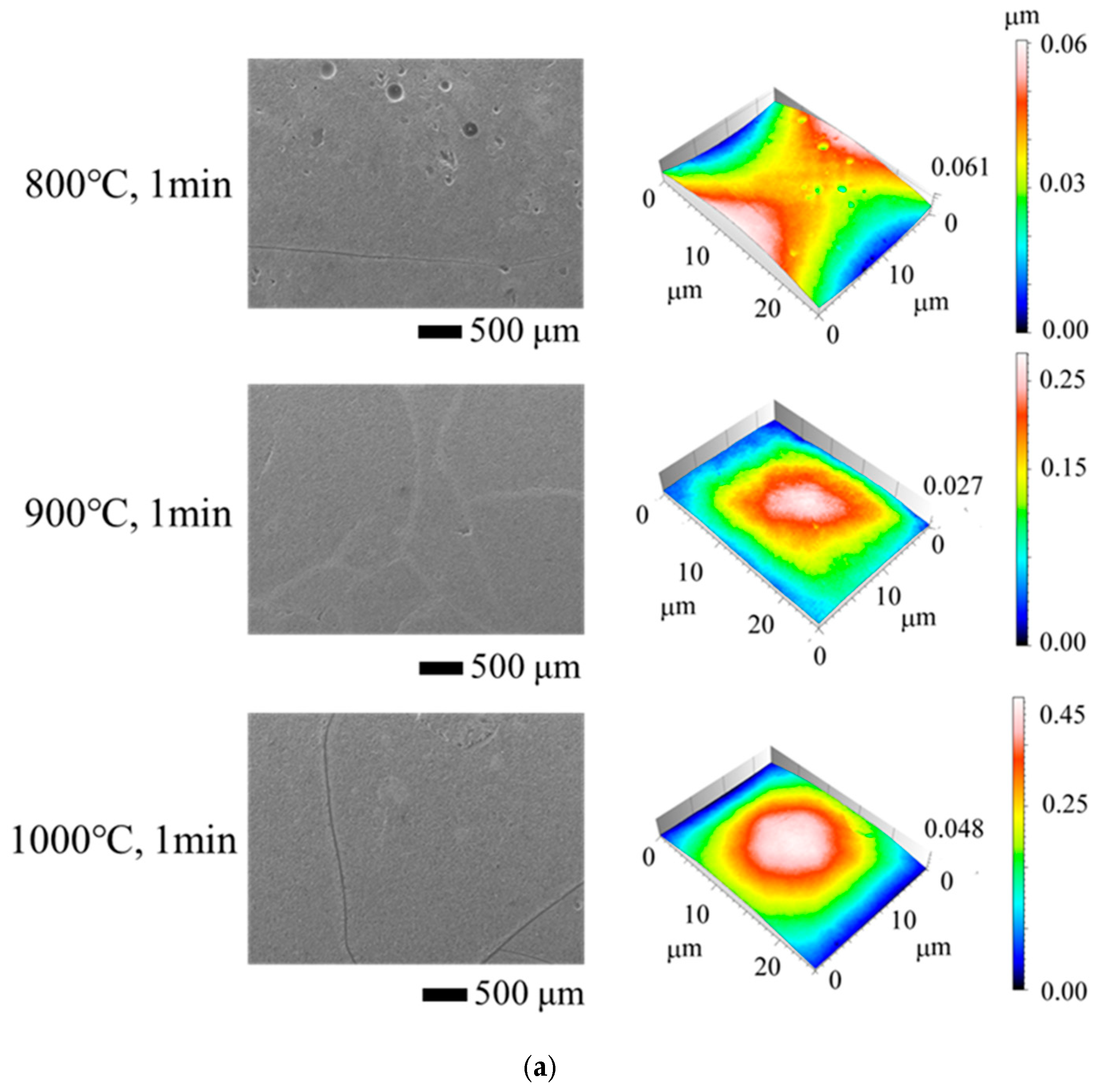

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madeddu, S.; Ueckerdt, F.; Pehl, M.; Peterseim, J.; Lord, M.; Kumar, K.A.; Krüger, C.; Luderer, G. The CO2 reduction potential for the European industry via direct electrification of heat supply (power-to-heat). Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtenböhmer, S.; Nilsson, L.J.; Åhman, M.; Schneider, C. Decarbonising the energy intensive basic materials industry through electrification—Implications for future EU electricity demand. Energy 2016, 115, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Hamagata, S.; Nagai, Y.; Nishio, K.; Tagashira, N. A survey on energy usage and electrification potential in industrial sectors toward shaping future socio-economic visions. J. Jpn. Soc. Energy Resour. 2020, 41, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Leisin, M. Branchensteckbrief der Glasindustrie. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/E/energiewende-in-der-industrie-ap2a-branchensteckbrief-glas.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Delgado Sancho, L.; Sissa, A.Q.; Scalet, B.M.; Roudier, S.; Garcia Muñoz, M. Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Manufacture of Glass, Industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, T.; Guminski, A.; Rouyrre, E.; von Roon, S. Branchensteckbrief der NEMetallindustrie, SISDE17915. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/E/energiewende-in-der-industrie-ap2a-branchensteckbrief-metall.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Schlemme, J.; Schimmel, M.; Achtelik, C. Branchensteckbrief der Eisen- und Stahlindustrie. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/E/energiewende-in-der-industrie-ap2a-branchensteckbrief-stahl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Schmitz, A.; Kamiński, J.; Scalet, B.M.; Soria, A. Energy consumption and CO2 emissions of the European glass industry. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, P. CO2 emission from container glass in China, and emission reduction strategy analysis. Carbon Manag. 2018, 9, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zier, M.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. A review of decarbonization options for the glass industry. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 10, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Latifi, M.; Chaouki, J. Electrification of materials processing via microwave irradiation: A review of mechanism and applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 193, 117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Fujii, S.; Suzuki, E.; Maitani, M.M.; Tsubaki, S.; Chonan, S.; Fukui, M.; Inazu, N. Smelting magnesium metal using a microwave Pidgeon method. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubertova, M.; Havlik, T.; Parilak, L.; Derin, B.; Trpcevska, J. The effects of microwave-assisted leaching on the treatment of electric arc furnace dusts (EAFD). Arch. Metall. Mater. 2020, 65, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kashimura, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Sato, M.; Yoneda, S.; Kishima, T.; Horikoshi, S.; Yoshikawa, N.; Mitani, T.; Shinohara, N. Rapid and in-situ transformations of asbestos into harmless waste by microwave rotary furnace: Application of microwave heating to rubble processing of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2014, 19, 04014041. [Google Scholar]

- Ioana, A.; Paunescu, L.; Constantin, N.; Pollifroni, M.; Deonise, D.; Petcu, F.S. Glass foam from flat glass waste produced by the microwave irradiation technique. Micromachines 2022, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwan, W.; Yasaka, P.; Boonin, K.; Khondara, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kothan, S.; Chanlek, N.; Kanjanaboos, P.; Phuphathanaphong, N.; Sareein, T.; et al. A comparative study of microwave assisted and conventional melting techniques to glass properties. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 224, 112011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Mandal, B.; Illath, K.; Ajithkumar, T.G.; Halder, A.; Sinha, P.K.; Sen, R. Preparation of colourless phosphate glass by stabilising higher Fe [II] in microwave heating. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.E.; Flores Rivera, F.L.; Pérez-Sánchez, G.G.; Figueroa, I.A. Novel energy-efficient microwave-assisted synthesis of Zn3(PO4)2: Er3+ glasses for optical amplification at 1550 nm. Opt. Mater. 2025, 170, 117714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Mandal, B.; Mahanty, S.; Sen, R.; Mandal, A.K. A comparative property investigation of lithium phosphate glass melted in microwave and conventional heating. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2017, 40, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Biswas, K.; Annapurna, K.; Guha, C.; Sen, R. Preparation of alumino-phosphate glass by microwave radiation. J. Mater. Res. 2013, 28, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, G. Preparation of Phosphate Glass by the Conventional and Microwave Melt-Quenching Methods and Research on Its Performance. Materials 2025, 18, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, N.; Pilania, R.K.; Sooraj, K.P.; Ranjan, M.; Sarker, D.; Dube, C.L. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of non-stoichiometric tungsten oxide doped borosilicate glasses for NIR shielding application. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 24470–24480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbroek, C.D.; Bitting, J.; Craglia, M.; Azevedo, J.M.; Cullen, J.M. Global material flow analysis of glass. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Sen, R. Microwave absorption of barium borosilicate, zinc borate, Fe-doped alumino-phosphate glasses and its raw materials. Technologies 2015, 3, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Y.; Sinha, P.K.; Mandal, A.K. Effect of melting time on volatility, OH in glass in microwave processing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 36, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashimura, K.; Hasegawa, N.; Suzuki, S.; Hayashi, M.; Mitani, T.; Shinohara, N.; Nagata, K. Effects of relative density on microwave heating of various carbon powder compacts microwave-metallic multi-particle coupling using spatially separated magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 024902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Peelamedu, R.; Hurtt, L.; Cheng, J.; Agrawal, D. Definitive experimental evidence for microwave effects: Radically new effects of separated E and H fields, such as decrystallization of oxides in seconds. Mater. Res. Innov. 2002, 6, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Mouris, J.; Hutcheon, R.; Huang, X. Microwave penetration depth in materials with non-zero magnetic susceptibility. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, N.; Kashimura, K.; Hashiguchi, M.; Sato, M.; Horikoshi, S.; Mitani, T.; Shinohara, N. Detoxification mechanism of asbestos materials by microwave treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 284, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIS B 7071-2; Optics and Photonics—Test Method for Refractive Index of Optical Glasses—Part 2: V-Block Refractometer Method. Japanese Industrial Standards Committee (JISC): Tokyo, Japan, 2024. Available online: https://www.jisc.go.jp/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Rocha, A.C.P.; Silva, J.R.; Lima, S.M.; Nunes, L.A.O.; Andrade, L.H.C. Measurements of refractive indices and thermo-optical coefficients using a white-light Michelson interferometer. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 6639–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhat, M.; El-Zaiat, S.Y.; Omar, M.F.; Farag, S.S.; Kamel, S.M. Refraction and dispersion measurement using dispersive Michelson interferometer. Opt. Commun. 2017, 393, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHOTT Optical Glass Datasheet Collection; SCHOTT AG: Mainz, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://www.schott.com (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Polyanskiy, M.N. Refractive Index Database. Available online: https://refractiveindex.info (accessed on 2 December 2025).

| SiO2 | Na2B4O7 | BaCO3 | Na2CO3 | K2CO3 | Sb2O3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64.46 | 13.66 | 3.37 | 6.89 | 11.53 | 0.09 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miyata, T.; Kashimura, K.; Momono, K. Raw Material Heating and Optical Glass Synthesis Using Microwaves. Processes 2026, 14, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010054

Miyata T, Kashimura K, Momono K. Raw Material Heating and Optical Glass Synthesis Using Microwaves. Processes. 2026; 14(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiyata, Takeshi, Keiichiro Kashimura, and Kiyoyuki Momono. 2026. "Raw Material Heating and Optical Glass Synthesis Using Microwaves" Processes 14, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010054

APA StyleMiyata, T., Kashimura, K., & Momono, K. (2026). Raw Material Heating and Optical Glass Synthesis Using Microwaves. Processes, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010054