Temporal Tracking of Metabolomic Shifts in In Vitro-Cultivated Kiwano Plants: A GC-MS, LC-HRMS-MS, and In Silico Candida spp. Protein and Enzyme Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Seed Material

2.2. Plant Material and In Vitro Culture Initiation

2.3. Preparation of the Samples for GC-MS and LC-MS

2.4. GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.5. LC-HRMS-MS Analysis of Non-Volatile Compounds

2.6. Molecular Docking Studies

2.7. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Compound Analysis of In Vitro Plant Tissue Culture of C. metuliferus

3.2. LC-MS-Orbitrap Analysis of In Vitro Plant Tissue Culture of C. metuliferus

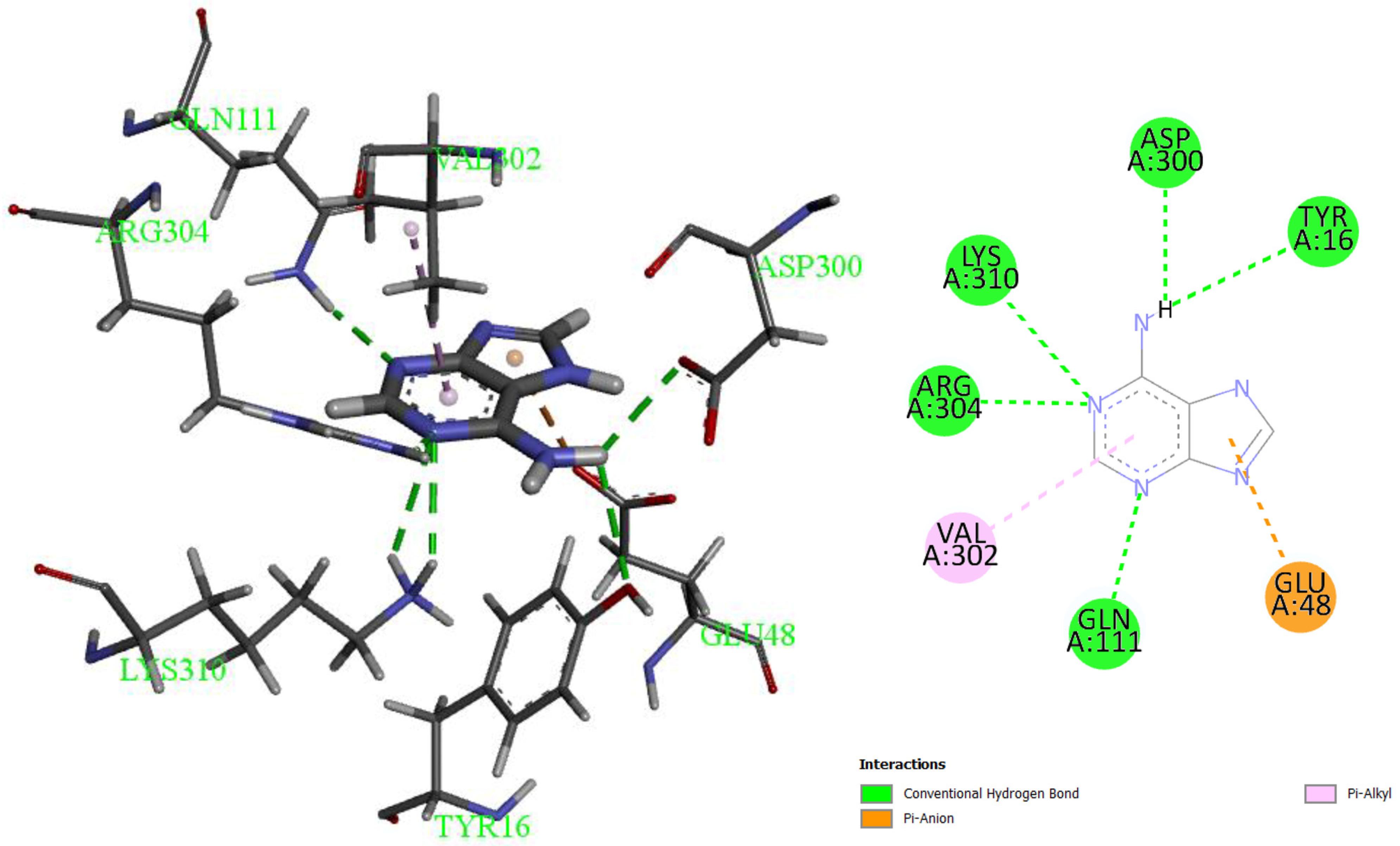

3.3. Molecular Modeling

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Debnah, M.; Malik, C.; Bisen, P. Micropropagation: A tool for the production of high quality plant-based medicines. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2006, 7, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-Hassani, E.; Motafakkerazad, R.; Razeghi, J.; Kosari-Nasab, M. The effects of methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid on the production of secondary metabolites in organ culture of Ziziphora persica. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019, 138, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Reddy, M.P. In vitro Plant Propagation: A Review. J. For. Sci. 2011, 27, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Owino, M.H.; Gichimu, B.M.; Muturi, P.W. Agro-morphological characterization of horned melon (Cucumis metuliferus) accessions from selected agro-ecological zones in Kenya. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2020, 14, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuru, M.; Nmom, F. A Review on the Economic Uses of Species of Cucurbitaceae and Their Sustainability in Nigeria. Am. J. Plant Biol. 2017, 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bester, S.P.; Condy, G. Cucumis metuliferus. Fl. Pl. Africa 2013, 63, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shopo, B.; Mapaya, R.J.; Maroyi, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants traditionally used in Gokwe South District, Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenya, S.S.; Maroyi, A. Plants Used by Bapedi Traditional Healers to Treat Asthma and Related Symptoms in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 2183705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyanwu, A.A.; Jimam, N.S.; Omale, S.; Wannang, N.N. Antiviral activities of Cucumis metuliferus fruits alkaloids on Infectious Bursal Disease Virus (IBDV). J. Phytopharmacol. 2017, 6, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omokhua-Uyi, A.G.; Van Staden, J. Phytomedicinal relevance of South African Cucurbitaceae species and their safety assessment: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 259, 112967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omale, S.; Wuyep, N.N.; Auta, A.; Wannang, N.N. Anti-ulcer properties of alkaloids isolated from the fruit pulp of Cucumis metuliferous (Cucurbitaceae). Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 2586–2588. [Google Scholar]

- Jimam, N.S.; Wannang, N.N.; Omale, S.; Gotom, B. Evaluation of the Hypoglycemic Activity of Cucumis metuliferus (Cucurbitaceae) Fruit Pulp Extract in Normoglycemic and Alloxan- Induced Hyperglycemic Rats. J. Young Pharm. 2010, 2, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzioni, A.; Mendlinger, S.; Ventura, M. Improvement of the appearance and taste of kiwano fruits from export to the ornamental and consumer markets. Acta Hortic. 1996, 434, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliero, A.A.; Gumi, A.M. Studies on the germination, chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of Cucumis metuliferus. Ann. Biol. Res. 2012, 3, 4059–4064. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce, A.; Flores-Maldonado, C.; Contreras, R.G. Cardiac Glycosides: From Natural Defense Molecules to Emerging Therapeutic Agents. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşarcă, S.; Tanase, C.; Muntean, D.L. Therapeutic aspects of catechin and its derivatives—An update. Acta Biol. Marisiensis 2019, 2, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuioc, A.C.; Botezatu, A.V.D.; Furdui, B.; Vinatoru, C.; Maggi, F.; Caprioli, G.; Dinica, R.M. Comparative Study of the Chemical Compositions and Antioxidant Activities of Fresh Juices from Romanian Cucurbitaceae Varieties. Molecules 2020, 25, 5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Cisowski, W. Flavonoids from some species of the genus Cucumis. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2001, 29, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, J.G.; Sodipo, O.A.; Kwaghe, A.V.; Sandabe, U.K. Uses of Cucumis metuliferus: A Review. Cancer Biol. 2015, 5, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rodriguez, M.A.; Vazquez-Oderiz, M.L.; Lopez-Hernandez, J.; Simal-Lozano, J. Physical and Analytical Characteristics of the Kiwano. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1992, 5, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaye, I.U.; Aliero, A.A.; Muhammad, S.; Bilbis, L.S. Comparative Evaluation of Amino Acid Composition and Volatile Organic Compounds of Selected Nigerian Cucurbit Seeds. Pak. J. Nutr. 2012, 11, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadou, H.; Sabo, H.; Alma, M.M.; Saadou, M.; Leger, C.L. Chemical content of the seeds and physico-chemical characteristic of the seed oils from Citrullus colocynthis, Coccinia grandis, Cucumis metuliferus and Cucumis prophetarum of Niger. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2007, 21, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-Sai, B.; Wahnou, H.; Benayad, S.; Rabbaa, S.; Laaziouez, Y.; El Kebbaj, R.; Limami, Y.; Duval, R.E. Gamma-Tocopherol: A Comprehensive Review of Its Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2024, 30, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aničić, N.; Matekalo, D.; Skorić, M.; Gašić, U.; Nestorović Živković, J.; Dmitrović, S.; Božunović, J.; Milutinović, M.; Petrović, L.; Dimitrijević, M.; et al. Functional iridoid synthases from iridoid producing and non-producing Nepeta species (subfam. Nepetoidae, fam. Lamiaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, D.; Gašić, U.; Uba, A.I.; Zengin, G.; Rajaković, M.; Stevanović, M.; Drakulić, D. Chemical profiling of Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm., biological potential of the herbal extract, molecular modeling and KEGG pathway analysis. Fitoterapia 2024, 177, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, D.; Đorđevski, N.; Rajaković, M.; Filipović, B.; Božunović, J.; Bolevich, S.; Zengin, G.; Bolevich, S.; Gašić, U.; Soković, M. Investigation of Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Verbena officinalis and Their Biological Effects in the Extraction by Four Butanol/Ethanol Solvent Combinations. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, T.; Freyss, J.; Von Korff, M.; Rufener, C. DataWarrior: An Open-Source Program for Chemistry Aware Data Visualization and Analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Ruth, H.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, D.; Letizia, C.S.; Api, A.M. Fragrance material review on phytol. Food Chem. Tox. 2010, 48, S59–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, T.; Sultana, R.; Shahin, H.D.; Chakraborthy, M.; Gulzar Ahmed, M. Phytol A Phytoconstituent, Its Chemistry And Pharmacological Actions. GIS Sci. J. 2021, 8, 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Requena, S.; Montiel, C.; Máximo, F.; Gómez, M.; Murcia, M.D.; Bastida, J. Esters in the Food and Cosmetic Industries: An Overview of the Reactors Used in Their Biocatalytic Synthesis. Materials 2024, 17, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, S.; Matsuda, K.; Hasebe, F.; Shiraishi, T.; Shin-Ya, K.; Kuzuyama, T.; Nishiyama, M. Guanidyl modification of the 1-azabicyclo [3.1.0]hexane ring in ficellomycin essential for its biological activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 5137–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivashanmugam, M.; Jaidev, J.; Umashankar, V.; Sulochana, K.N. Ornithine and its role in metabolic diseases: An appraisal. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 86, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.K. Vitamin E and oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 11, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Woo, E.R.; Lee, D.G. Apigenin induces cell shrinkage in Candida albicans by membrane perturbation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Stecko, J.; Sobieraj, J.; Szymańska, N.; Kozłowska, J. Naringenin and Its Derivatives—Health-Promoting Phytobiotic against Resistant Bacteria and Fungi in Humans. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound Name | tR, min | Molecular Formula | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-methoxyethyl 2-propenoate | 3.94 | C6H10O3 | + | ||||

| Methyl 2-methylbutanoate | 4.31 | C6H12O2 | + | + | + | + | |

| Methyl 2-oxopropanoate | 4.54 | C4H6O3 | + | + | + | ||

| 4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carbonitrile | 5.00 | C3H2N4 | + | + | |||

| Methyl pyrazine | 5.00 | C5H6N2 | + | + | + | ||

| Propoxybenzene | 5.17 | C9H12O | + | ||||

| 2-methyl-1H-pyrrole | 5.20 | C5H7N | + | ||||

| 2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole | 5.36 | C6H9N | + | + | |||

| Dimethylbenzene | 5.59 | C8H10 | + | + | |||

| 3-methoxy-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane carboxylic acid | 5.82 | C7H12O3 | + | ||||

| 2-butoxyethanol | 6.05 | C6H14O2 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Butyrolactone | 6.16 | C4H6O2 | + | + | + | + | |

| 2,3-dimethylpyrazine | 6.21 | C6H8N2 | + | ||||

| 2,3-dihydro-4H-pyran-4-one | 6.26 | C5H6O2 | + | + | + | ||

| 3-ethoxypentane | 6.59 | C7H16O | + | + | + | + | + |

| Benzaldehyde | 6.69 | C7H6O | + | + | + | + | |

| 2,6-dimethyloct-2-ene | 6.76 | C10H20 | + | ||||

| 2,4-dihydroxy-2,5-dimethylfuran-3-one | 6.87 | C6H8O4 | + | + | + | ||

| 5-methylnon-4-ene | 6.88 | C10H20 | + | + | + | + | |

| 2-propen-1-ol | 6.95 | C3H6O | + | ||||

| 1H-pyrazol-5-amine | 7.02 | C3H5N3 | + | + | + | + | |

| Decane | 7.04 | C10H22 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine | 7.11 | C7H10N2 | + | + | + | ||

| 2-ethyl-1-hexanol | 7.33 | C8H18O | + | ||||

| 2,4-dioxohexahydro-1,3,5-triazine | 7.39 | C3H5N3O2 | + | ||||

| 1-phenyl-1,2-propanediol | 7.41 | C9H12O2 | + | + | |||

| Benzeneacetaldehyde | 7.51 | C8H8O | + | ||||

| 1-(3-methyl-2H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethanone | 7.53 | C6H8N2O | + | ||||

| 2,4,5-trihydroxypyrimidine | 7.56 | C4H4N2O3 | + | + | |||

| 6,6-dimethylundecane | 7.65 | C13H28 | + | ||||

| Pyrrolidin-2-one | 7.69 | C4H7NO | + | + | + | + | |

| prop-2-yn-1-yl heptan-2-ylcarbamate | 7.77 | C11H19NO2 | + | ||||

| 3-hydroxy-4-methylbenzaldehyde | 7.82 | C8H8O2 | + | + | + | ||

| 1-Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | 7.86 | C5H9N | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2,6-diethylpyrazine | 7.89 | C8H12N2 | + | ||||

| Methoxyphenol | 7.93 | C7H8O2 | + | + | |||

| Undecane | 7.96 | C11H24 | + | + | + | ||

| 2-methyl-6-(1-propenyl)pyrazine | 8.00 | C8H10N2 | + | ||||

| 2,3-butanedione monoxime | 8.04 | C4H7NO2 | + | ||||

| 1-phenylethanol | 8.13 | C8H10O | + | ||||

| 2,3-dihydro-1H-Isoindole | 8.18 | C8H9N | + | ||||

| 3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-2,3-dihydropyran-4-one | 8.38 | C6H8O4 | + | + | + | + | |

| Butanoic acid | 8.48 | C4H8O2 | + | ||||

| 4-vinyl-1H-imidazole | 8.55 | C5H6N2 | + | ||||

| 1H-Tetrazole | 8.70 | CH2N4 | + | + | |||

| Benzene-1,2-diol (catechol) | 8.74 | C6H6O2 | + | + | |||

| 2,3-dihydro-1-benzofuran | 8.91 | C8H8O | + | + | + | + | |

| Oxan-3-one | 9.01 | C5H8O2 | + | ||||

| Pyrrolidine | 9.08 | C4H9N | + | + | + | ||

| 1-(1-butoxypropan-2-yloxy)propan-2-ol | 9.11 | C10H22O3 | + | + | + | ||

| 2-(2-hydroxypropoxy)propan-1-ol | 9.11 | C6H14O3 | + | + | + | + | |

| ethyl 2-amino-4-methylpentanoate | 9.22 | C8H17NO2 | + | ||||

| 3-ethenyl-4-methylpyrrole-2,5-dione | 9.23 | C7H7NO2 | + | + | |||

| 2-[(2-cyanoacetyl)oxy]ethyl 2-methylprop-2-enoate | 9.56 | C9H11NO4 | + | + | + | ||

| m-aminophenylacetylene | 9.57 | C8H7N | + | + | |||

| 2,5-diaminopentanoic acid (ornithine) | 9.62 | C5H12N2O2 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 9.69 | C9H10O2 | + | + | |||

| 3-aminopiperidine-2,6-dione | 9.71 | C5H8N2O2 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1H-Imidazole-2-carboxaldehyde | 9.83 | C4H4N2O | + | ||||

| 3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde | 9.96 | C6H8N2O | + | ||||

| Methyl 5-oxo-prolinate | 10.07 | C6H9NO3 | + | + | |||

| Piperidine-2,6-dione (glutarimide) | 10.18 | C5H7NO2 | + | ||||

| Pyridine-4-carboxamide (Isonicotinamide) | 10.20 | C6H6N2O | + | + | + | ||

| 1-ethyl-1H-indole | 10.23 | C10H11N | + | ||||

| 4-(dimethylamino)benzonitrile | 10.23 | C9H10N2 | + | ||||

| 6-acetamido-N-acetyl-2-amino-N-(naphthalen-2-yl)hexanamide | 10.31 | C20H25N3O3 | + | ||||

| Isoindole-1,3-dione (phthalimide) | 10.69 | C8H5NO2 | + | + | |||

| N,N’-(2-hydroxytrimethylene)diphthalimide | 10.70 | C19H14N2O5 | + | ||||

| Ethyl tridec-2-yn-1-yl terephthalate | 10.87 | C23H32O4 | + | ||||

| 3,5-dihydroxybenzaldehyde | 10.93 | C7H6O3 | + | ||||

| 3-Hydroxybenzaldehyde oxime | 10.93 | C7H7NO2 | + | ||||

| (2,4-ditert-butylphenyl) 5-hydroxypentanoate | 10.97 | C19H30O3 | + | + | + | + | |

| 1-(2-hydroxy-4,5-dimethylphenyl)ethanone | 11.09 | C10H12O2 | + | + | |||

| 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxamide | 11.10 | C5H6N2O | + | ||||

| ethyl 2-amino(N-dimethylaminomethylene)-3-phenylpropanoate | 11.39 | C14H20N2O2 | + | ||||

| 2-methylnaphthalen-1-amine | 11.46 | C11H11N | + | ||||

| 2,2,4-trimethylpentane-1,3-diyl bis(2-methylpropanoate) | 11.52 | C16H30O4 | + | ||||

| 2-methyl-4-pyridinamine 1-oxide | 11.53 | C6H8N2O | + | + | |||

| 3-acetyl-4-hydroxy-6-methyl-2-pyridone | 11.58 | C8H9NO3 | + | ||||

| 1-(1-piperidino)cyclohexene | 11.71 | C11H19N | + | ||||

| 7H-Purin-6-amine (adenine) | 12.30 | C5H5N5 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2-anilino-N,N-dimethylacetamide | 12.31 | C10H14N2O | + | ||||

| 2,5-diallyldecahydroquinoline | 12.31 | C15H25N | + | ||||

| 2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)ethanamine (tryptamine) | 12.41 | C10H12N2 | + | ||||

| nonyl 2-((methoxycarbonyl)amino)pentanoate | 12.42 | C16H31NO4 | + | ||||

| bis(2-formylphenyl) 2,2′-oxydiacetate | 12.74 | C18H14O7 | + | ||||

| 7,11,15-trimethyl-3-methylidenehexadec-1-ene (neophytadiene) | 12.82 | C20H38 | + | + | + | + | |

| 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-ene | 12.85 | C20H40 | + | + | |||

| 1,1′-methylenediazetidine | 12.85 | C7H14N2 | + | ||||

| cyclohexyl (4-methylpentyl)phthalate | 13.02 | C18H24O4 | + | ||||

| 1-O-(2-methylpropyl) 2-O-octan-4-yl benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | 13.03 | C20H30O4 | + | ||||

| butyl pentan-2-yl phthalate | 13.03 | C17H24O4 | + | ||||

| Methyl hexadecanoate | 13.25 | C17H34O2 | + | + | + | ||

| 7,9-ditert-butyl-1-oxaspiro[4.5]deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione | 13.32 | C17H24O3 | + | + | |||

| Hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid) | 13.41 | C16H32O2 | + | + | + | + | |

| Dibutyl phthalate | 13.50 | C16H22O4 | + | ||||

| Methyl 2-methylhexadecanoate | 13.59 | C18H36O2 | + | ||||

| cyclohexane-1,4-dimethanol diacetate | 14.13 | C12H20O4 | + | + | + | ||

| 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-en-1-ol (phytol) | 14.19 | C20H40O | + | + | + | + | + |

| Methyl stearate | 14.23 | C19H38O2 | + | ||||

| Hexadecanamide | 14.49 | C16H33NO | + | + | |||

| Nonanamide | 14.49 | C9H19NO | + | ||||

| Bis(2-ethylhexyl) 2-butenedioate | 14.69 | C20H36O4 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5,7-dimethylpyrimido-[3,4-a]indole | 14.79 | C13H12N2 | + | + | |||

| 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl ethyl carbonate | 14.94 | C7H15NO3 | + | ||||

| Glycidyl tetradecanoate | 15.00 | C17H32O3 | + | + | + | ||

| Octadec-9-enamide | 15.31 | C18H35NO | + | + | + | + | + |

| Heptadeca-1,8,11,14-tetraene | 15.33 | C17H28 | + | ||||

| Tricyclo[4.3.1.0(2,5)]decane | 15.79 | C10H16 | + | + | |||

| 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl hexadecanoate | 15.89 | C19H38O4 | + | + | + | ||

| Octadec-17-en-14-yn-1-ol | 16.70 | C18H32O | + | ||||

| 2,3-Dihydroxypropyl octadecanoate | 16.75 | C21H42O4 | + | ||||

| 2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyltetracosa-2,6,10,14,18,22-hexaene (supraene) | 17.31 | C30H50 | + | ||||

| 2-(4-methylphenyl)indolizine | 19.35 | C15H13N | + | ||||

| 2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)chroman-6-ol (α-tocopherol) | 19.45 | C29H50O2 | + |

| Compound Name | tR, min | Molecular Formula, [M—H]— | Calculated Mass, [M—H]— | Exact Mass, [M—H]— | Δ ppm | MS2 Fragments, (% Base Peak) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | ||||||

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside | 0.66 | C13H15O9— | 315.07216 | 315.07278 | −1.99 | 108.02177(49), 109.02966(34), 152.01178(100), 153.0195(50), 315.07251(35) |

| Gallic acid pentoside | 0.68 | C12H13O9— | 301.05651 | 301.05723 | −2.39 | 125.02458(43), 149.99619(5), 168.00658(100), 169.01462(10), 301.05676(82) |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid pentosyl hexoside | 0.72 | C18H23O13— | 447.11442 | 447.11485 | −0.98 | 108.02205(8), 109.02945(13), 152.01176(100), 153.01964(5), 315.07217(5), 447.11554(67) |

| Vanillic acid hexoside | 0.80 | C14H17O9— | 329.08781 | 329.08829 | −1.48 | 167.03508(100) |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid pentoside | 0.85 | C12H13O8— | 285.06159 | 285.06199 | −1.41 | 109.02968(26), 152.01163(19), 153.01958(100), 285.06195(32) |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid pentosyl pentoside | 1.14 | C17H21O12— | 417.10385 | 417.10411 | −0.63 | 108.02173(8), 109.02964(18), 152.01166(100), 241.07196(13), 417.10410(73) |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid hexoside | 1.17 | C13H15O8— | 299.07724 | 299.07760 | −1.21 | 93.03463(23), 137.02451(100) |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 2.68 | C7H5O4— | 153.01933 | 153.01951 | −1.14 | 109.02969(78), 153.01941(100) |

| Vanillic acid | 4.30 | C8H7O4— | 167.03498 | 167.03516 | −1.06 | 108.02194(46), 123.04408(5), 152.01152(28), 167.03532(100) |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid | 5.45 | C7H5O3— | 137.02442 | 137.02455 | −0.99 | 93.03468(100), 137.02461(51) |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | ||||||

| Ferulic acid hexoside | 4.05 | C16H19O9— | 355.10346 | 355.10350 | −0.14 | 134.03749(27), 149.06081(22), 175.04056(67), 191.07166(45), 193.05077(100), 235.06145(68) |

| Coumaric acid | 4.15 | C9H7O3— | 163.04007 | 163.04024 | −1.07 | 119.05038(100), 163.04027(11) |

| Ferulic acid | 5.06 | C10H9O4— | 193.05063 | 193.05079 | −0.81 | 134.03755(100), 149.06088(9), 178.02788(15), 193.05122(8) |

| Caffeic acid | 5.69 | C9H7O4— | 179.03498 | 179.03519 | −1.19 | 135.00087(100), 179.03587(21) |

| Methoxycinnamic acid | 6.45 | C10H9O3— | 177.05572 | 177.05590 | −1.03 | 145.02975(33), 162.03249(10), 177.05592(100) |

| Flavonoid glycosides | ||||||

| Isoorientin 2″-O-hexoside | 4.49 | C27H29O16— | 609.14611 | 609.14663 | −0.85 | 298.04852(74), 309.04111(69), 327.05148(48), 339.05124(24), 357.06216(32), 369.06125(13), 429.08282(40), 489.10437(100), 609.14557(11) |

| Isovitexin 2″-O-hexoside-7-O-hexoside | 4.87 | C33H39O20— | 755.20402 | 755.20477 | −1.00 | 293.04572(100), 311.05673(17), 323.05719(7), 341.06674(15), 413.08716(44), 635.16211(6) |

| Isovitexin 2″-O-hexoside | 4.90 | C27H29O15— | 593.15119 | 593.15175 | −0.94 | 293.04587(100), 311.05649(10), 323.05624(7), 341.06699(7), 413.08817(34), 473.10788(3) |

| Isovitexin 2″-O-hexoside-7-O-pentoside | 4.92 | C32H37O19— | 725.19345 | 725.19370 | −0.34 | 293.04623(100), 311.05737(22), 323.05554(14), 341.06769(18), 413.08798(42) |

| Apigenin 6-C-hexoside (Isovitexin) | 5.08 | C21H19O10— | 431.09837 | 431.09864 | −0.63 | 283.06143(15), 311.05634(100), 323.05588(7), 341.06659(39), 353.06714(4) |

| Kaempferol 3,7-di-O-rhamnoside | 5.13 | C27H29O14— | 577.15628 | 577.15711 | −1.43 | 283.02441(35), 284.03177(6), 285.04074(100), 430.09116(30), 431.09875(24) |

| Kaempferol 3-O-hexoside | 5.46 | C21H19O11— | 447.09329 | 447.09370 | −0.92 | 227.03535(4), 255.03033(11), 284.03290(100), 285.04065(27), 327.05139(2), 447.09360(18) |

| Apigenin 7-O-(6”-pentosyl)-hexoside | 5.52 | C26H27O14— | 563.14063 | 563.14169 | −1.88 | 269.04575(100), 563.14227(4) |

| Flavonoid aglycones | ||||||

| Patuletin | 6.32 | C16H11O8— | 331.04594 | 331.04676 | −2.49 | 165.99101(21), 181.01465(11), 287.01797(15), 316.02267(100), 331.04724(14) |

| Apigenin | 6.72 | C15H9O5— | 269.04555 | 269.04585 | −1.14 | 151.00407(3), 225.05812(2), 269.04584(100) |

| Naringenin | 6.72 | C15H11O5— | 271.06120 | 271.06156 | −1.33 | 107.01396(13), 119.05036(42), 151.00381(100), 177.01939(10), 271.06140(47) |

| Chrysoeriol | 6.76 | C16H11O6— | 299.05611 | 299.05667 | −1.87 | 284.03284(100), 285.03745(4) |

| Luteolin | 6.82 | C15H9O6— | 285.04046 | 285.04086 | −1.38 | 285.04089(100) |

| Cirsimaritin | 7.39 | C17H13O6— | 313.07176 | 313.07209 | −1.04 | 283.02496(100), 297.04062(16), 298.04840(80), 313.07242(23) |

| Biochanin | 7.91 | C16H11O5— | 283.06120 | 283.06175 | −1.96 | 268.03793(91), 283.06165(100) |

| Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-en-1-ol (phytol)) | −6.5 |

| 2,5-diaminopentanoic acid (ornithine) | −4.3 |

| 7H-Purin-6-amine (adenine) | −4.6 |

| 1-Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | −3.8 |

| Octadec-9-enamide | −6.2 |

| 8-deethyl-8-[but-3-enyl]-ascomycin (control) | −10.5 |

| Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-en-1-ol (phytol)) | −4.6 |

| 2,5-diaminopentanoic acid (ornithine) | −5.2 |

| 7H-Purin-6-amine (adenine) | −5.9 |

| 1-Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | −3.8 |

| Octadec-9-enamide | −4.4 |

| Inhibitor (control) * | −5.2 |

| Compounds | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-en-1-ol (phytol)) | −8.0 |

| 2,5-diaminopentanoic acid (ornithine) | −4.8 |

| 7H-Purin-6-amine (adenine) | −5.5 |

| 1-Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | −3.7 |

| Octadec-9-enamide | −7.2 |

| Inhibitor (control) * | −12.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rajaković, M.; Božunović, J.; Mišić, D.; Sofrenić, I.; Stojković, D.; Gašić, U. Temporal Tracking of Metabolomic Shifts in In Vitro-Cultivated Kiwano Plants: A GC-MS, LC-HRMS-MS, and In Silico Candida spp. Protein and Enzyme Study. Processes 2026, 14, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010056

Rajaković M, Božunović J, Mišić D, Sofrenić I, Stojković D, Gašić U. Temporal Tracking of Metabolomic Shifts in In Vitro-Cultivated Kiwano Plants: A GC-MS, LC-HRMS-MS, and In Silico Candida spp. Protein and Enzyme Study. Processes. 2026; 14(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleRajaković, Mladen, Jelena Božunović, Danijela Mišić, Ivana Sofrenić, Dejan Stojković, and Uroš Gašić. 2026. "Temporal Tracking of Metabolomic Shifts in In Vitro-Cultivated Kiwano Plants: A GC-MS, LC-HRMS-MS, and In Silico Candida spp. Protein and Enzyme Study" Processes 14, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010056

APA StyleRajaković, M., Božunović, J., Mišić, D., Sofrenić, I., Stojković, D., & Gašić, U. (2026). Temporal Tracking of Metabolomic Shifts in In Vitro-Cultivated Kiwano Plants: A GC-MS, LC-HRMS-MS, and In Silico Candida spp. Protein and Enzyme Study. Processes, 14(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010056