With the development of the global economy, population growth, and changes in the international landscape, the demand for energy continues to rise. Currently, China’s shale oil resources are widely distributed, of high quality, and estimated to exceed 100 billion tons in reserves, demonstrating enormous development potential. However, shale oil is one of the most challenging unconventional resources to extract. China’s shale oil is primarily found in continental sedimentary basins, influenced by orogeny and faulting, exhibiting characteristics such as low porosity, low permeability, strong heterogeneity, high stress differentials, and multiple thin layers [

1]. These factors result in suboptimal hydraulic fracturing performance in reservoirs.

Zheng Ning (ZN) Oilfield in this study faces three major challenges in hydraulic fracturing: the reservoir is tight and strongly heterogeneous, resulting in limited fracture half-lengths and uneven propagation; insufficient rock brittleness combined with a large horizontal stress difference suppresses the development of complex fracture networks; and the low formation pressure coefficient weakens fluid mobility, causing rapid production decline and single-well EUR far below economic viability.

In response to the aforementioned challenges, scholars have conducted extensive research in recent years. Zhang [

2] systematically investigated the influence of in-situ stress contrast on fracture initiation and propagation behavior during volumetric fracturing in shale oil reservoirs of Block Y, Ordos Basin, using a numerical simulation approach based on the cohesive zone model. Zheng [

3] investigated fracture morphology under various parameters through numerical simulations, revealing that hydraulic fracture propagation is jointly influenced by multiple factors, including stress field magnitude, direction, internal fracture pressure, and rock mechanical properties. Ni [

4] developed a phase-field model is and applied for investigating the hydraulic fracturing propagation in saturated poroelastic rocks with pre-existing fractures. Zheng [

5] developed a numerical model to simulate the interaction between hydraulic fractures and natural fractures. The simulations revealed that natural fractures can initiate and propagate under the influence of induced stress fields, without necessarily intersecting with hydraulic fractures. Tian [

6] found that the important controlling factor for the increase of moisture cut and the extension of the backflow period of the Mahu tight oil well group is the low formation pressure coefficient. Zhou [

7] investigated the hydraulic fracturing effect of groundwater on rock fractures and derived the tangential friction equation of hydrodynamic pressure acting on rock fractures. The study analyzed the relationship between crack orientation and the lateral pressure coefficient as well as the friction angle of the fracture plane. It was demonstrated that when the static lateral pressure coefficient of surrounding rock equals 1.0, the critical pressure becomes independent of crack orientation. Lu [

8,

9] simulated the influence of pore pressure gradient on fracture initiation and propagation by coupling seepage, stress, and damage. The study demonstrated that pore pressure gradient can effectively reduce fracture initiation pressure, with fractures tending to propagate toward regions of higher pore pressure. Liu [

10] proposed a new strategy for modeling the heterogeneity of structural and attribute models starting from the heterogeneity of the reservoir. Yu [

11] systematically revealed the spatiotemporal evolution law of the stress field during deep shale gas fracturing by establishing a four-dimensional dynamic stress field coupling model. Soroush Ahmad [

12] analyzed chemical stimulation approaches involving additives used to inhibit asphaltene precipitation, which can enhance oil mobility and improve production performance. Yang Mou et al. [

13] investigated inter-well stress interference and found that zipper fracturing can significantly increase stimulated rock volume and well productivity through stress shadow effects and enhanced diversion capability. CO

2 fracturing has recently attracted attention as an alternative stimulation fluid. Owing to its low viscosity, high diffusivity, and immunity to water-sensitivity effects, CO

2 can penetrate deeper into the fracture network and reduce formation damage during stimulation. Studies by Wang Jianxiang et al. [

14] indicate that CO

2 fracturing can promote fracture propagation, enhance hydrocarbon mobility, and provide additional benefits associated with partial carbon sequestration during the fracturing process. Compared to CO

2 fracturing and zipper fracturing, the intensive clustered fracturing method used in this study offers greater operational flexibility, eliminating the need for CO

2 injection or coordinated operations with adjacent wells. Additionally, intensive clustered fracturing can dynamically adjust cluster density and scale to better adapt to highly heterogeneous reservoirs, whereas CO

2 fracturing is limited by reservoir permeability, and zipper fracturing imposes higher requirements on well spacing and reservoir homogeneity.

Previous studies have investigated shale-oil hydraulic fracturing from four main perspectives: (1) fracture propagation mechanisms, (2) reservoir heterogeneity, (3) formation-pressure behavior, and (4) engineering optimization strategies. Although these works have provided valuable insights, several important limitations remain. Most existing studies focus on fracture morphology or heterogeneity, while the role of formation-energy enhancement during hydraulic fracturing has not been adequately addressed [

15,

16]. In addition, the quantitative relationship between improvements in the formation pressure coefficient and estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) has rarely been examined, and geological and engineering sweet spots are often evaluated separately rather than within an integrated optimization framework [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. These gaps are particularly evident in the ZN Oilfield. The reservoir is characterized by thin sand–shale interbeds, strong heterogeneity, low formation pressure coefficients, and large horizontal stress differences. These geological factors lead to uneven fracture propagation and limited stimulated reservoir volume, making conventional hydraulic-fracturing strategies less effective. Existing research provides limited guidance on how to enhance formation energy during stimulation or how to jointly optimize geological and engineering sweet spots under ultra-low-pressure reservoir conditions. Addressing these unresolved issues forms the core motivation for this study and provides the basis for the pressure-enhanced volumetric fracturing strategy proposed herein.

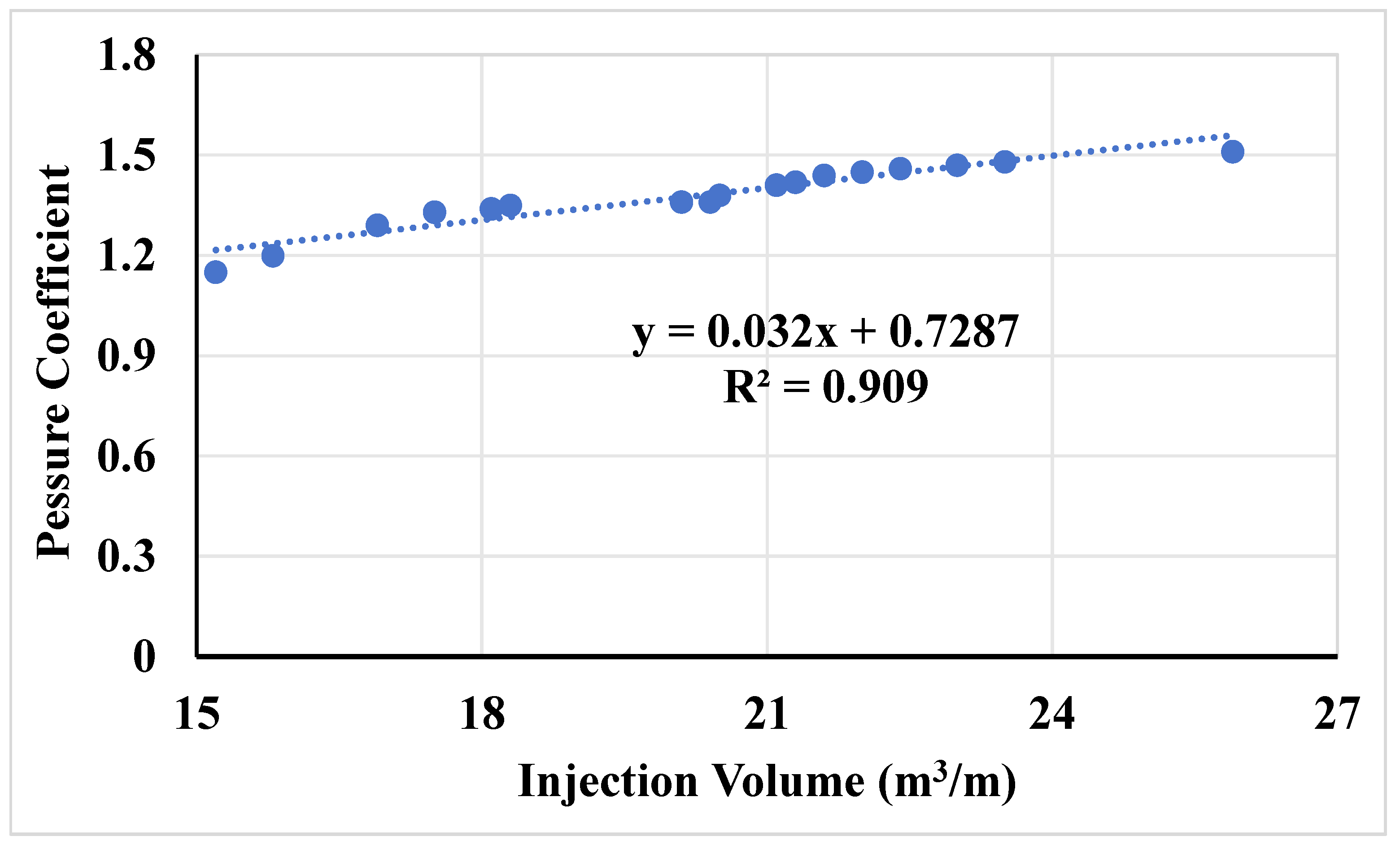

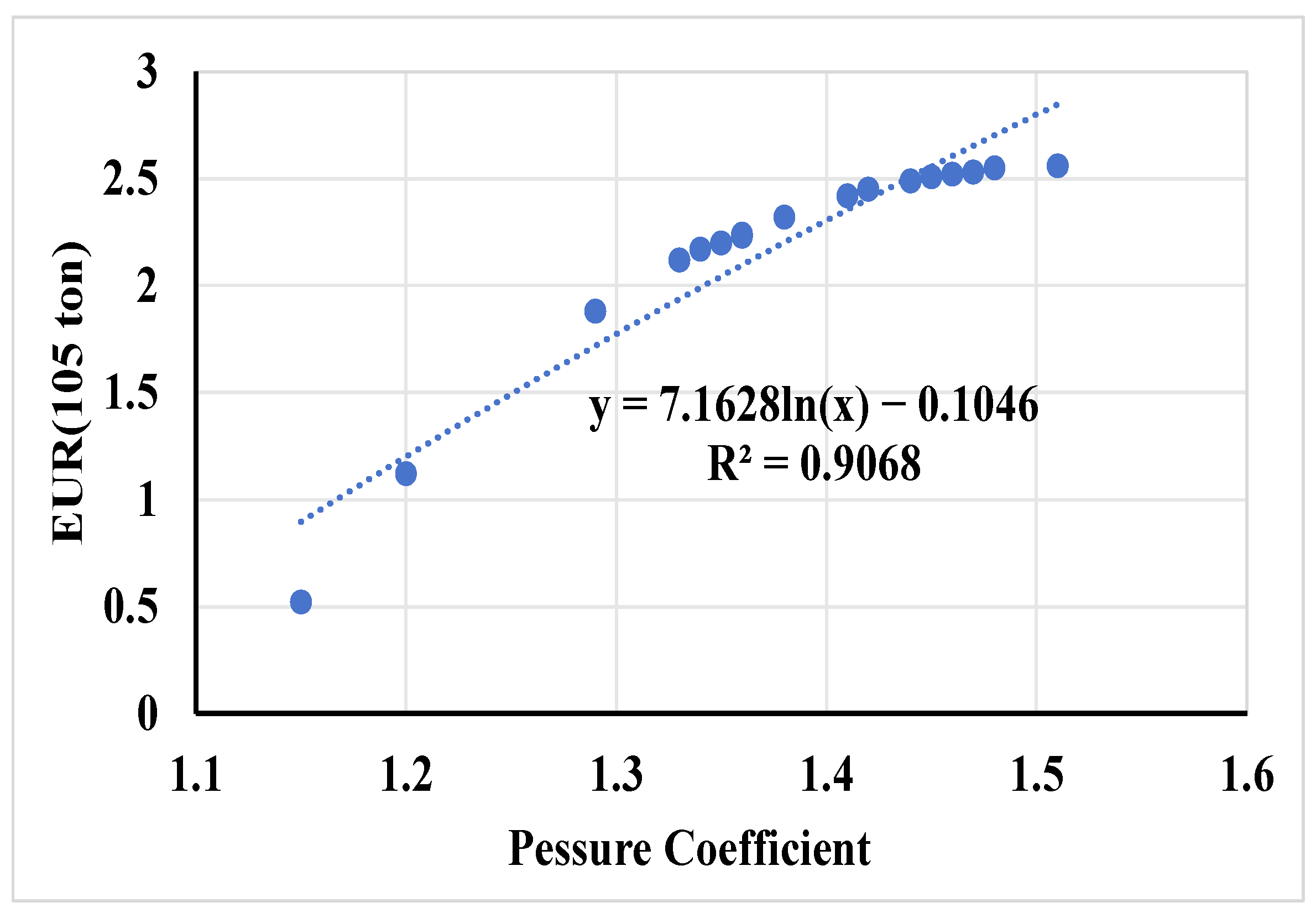

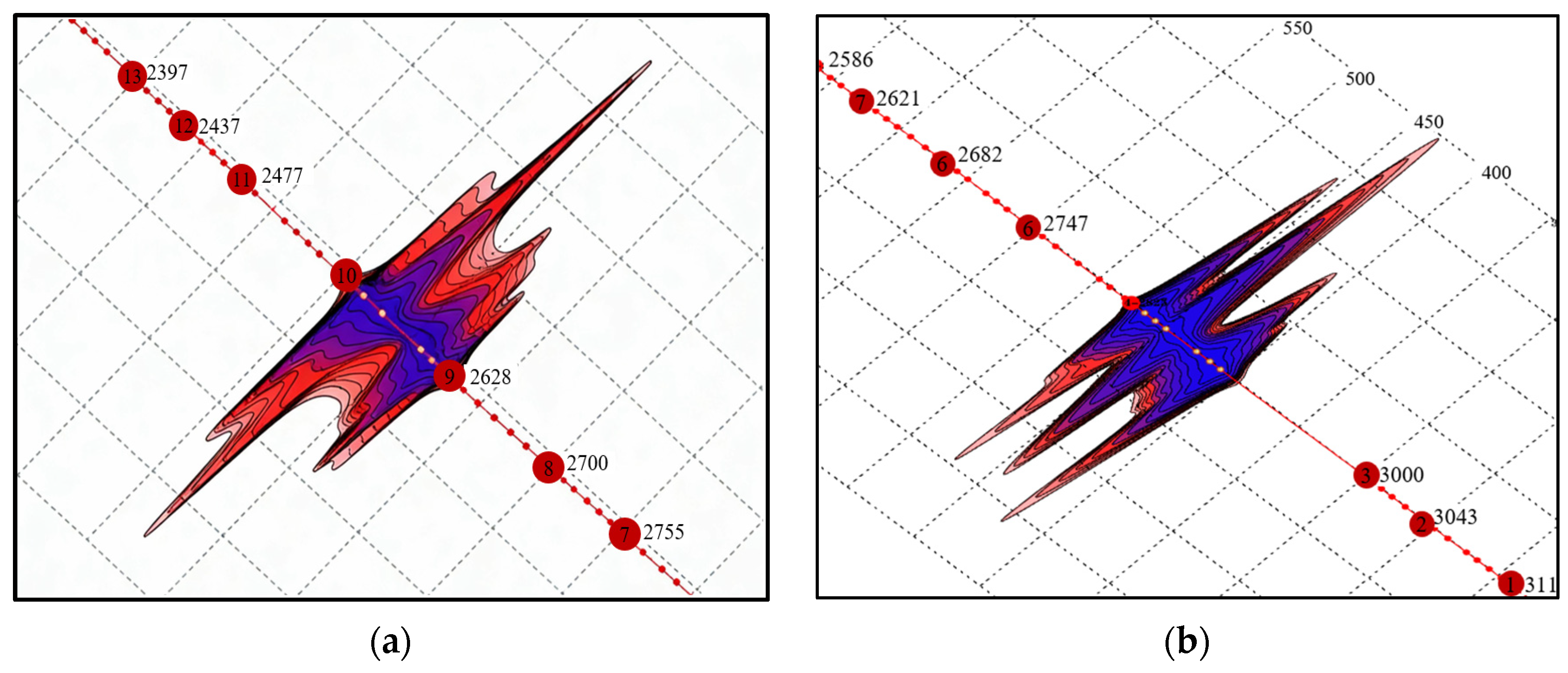

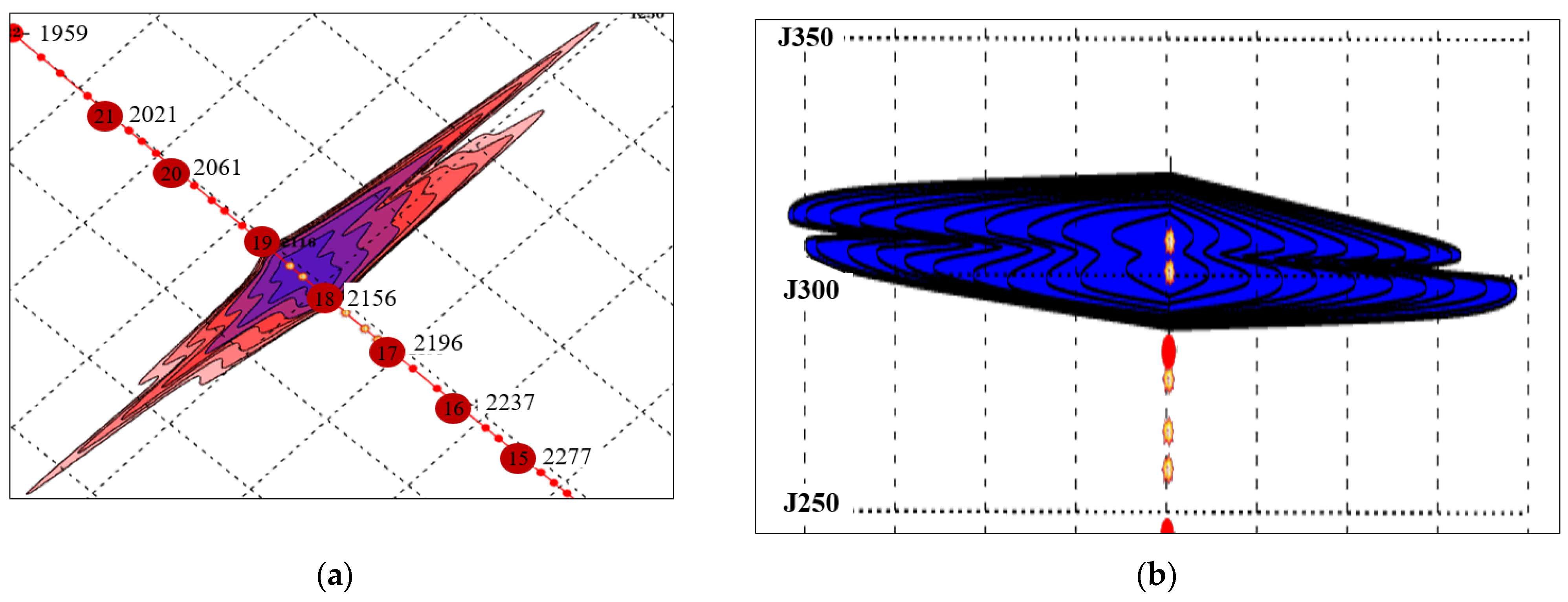

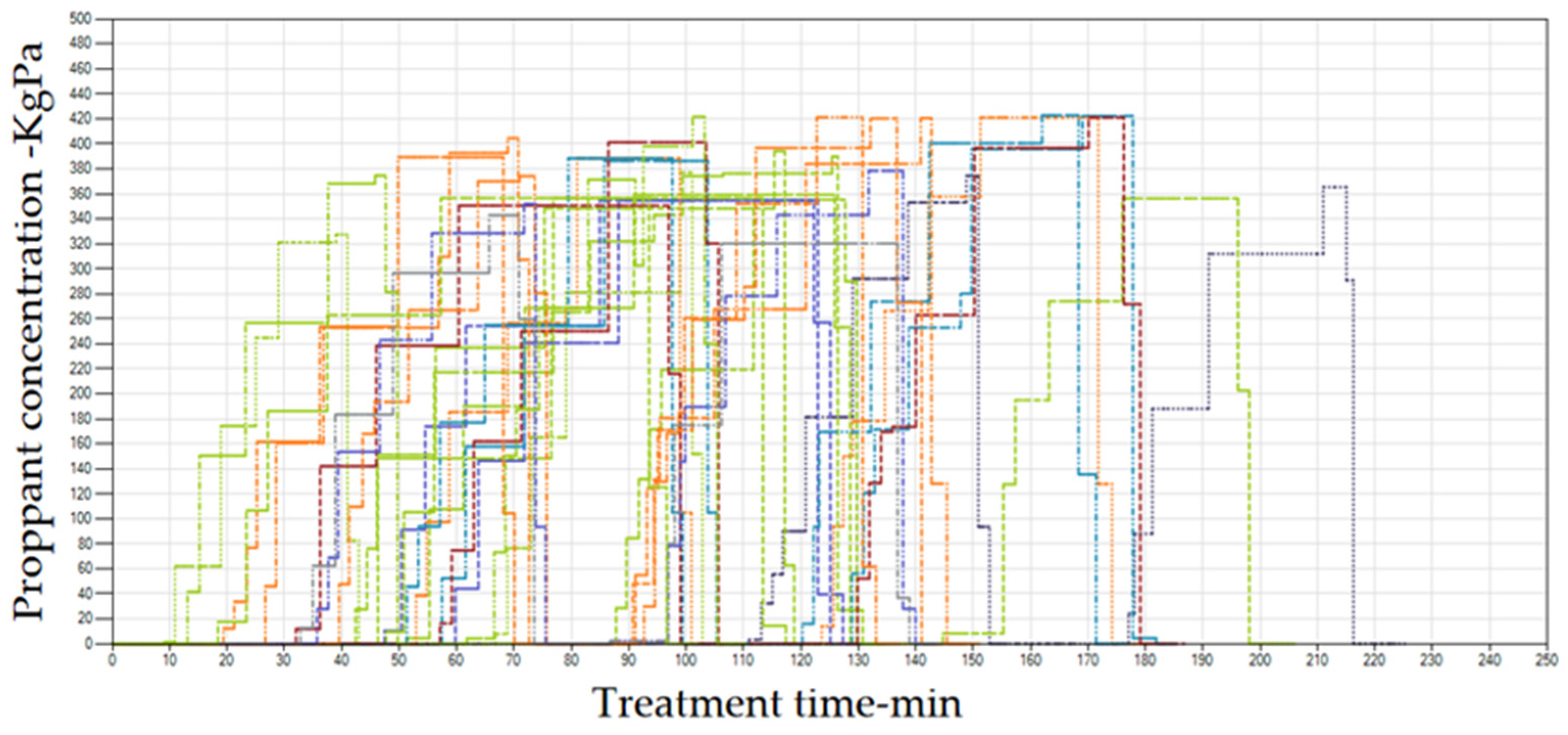

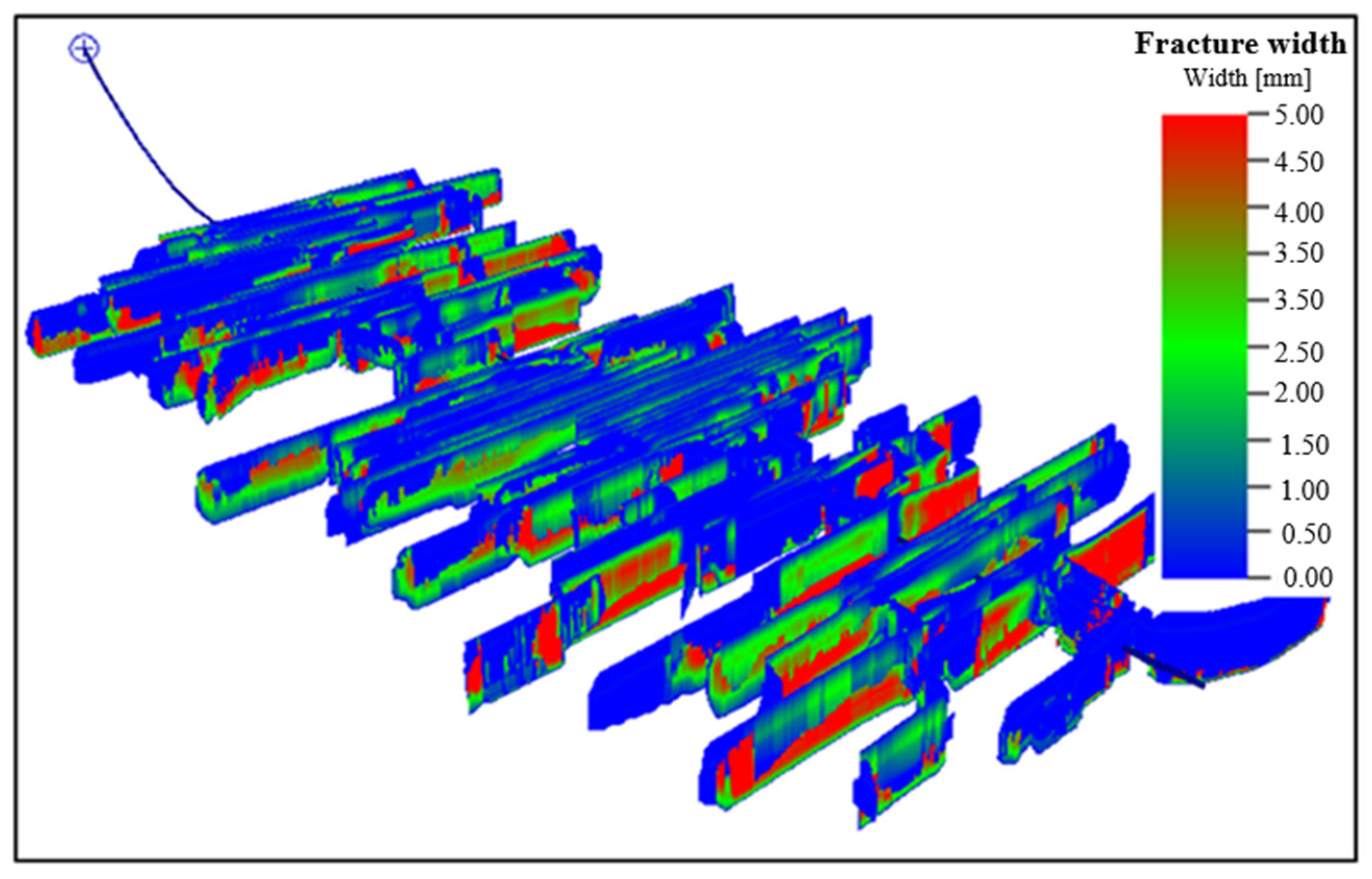

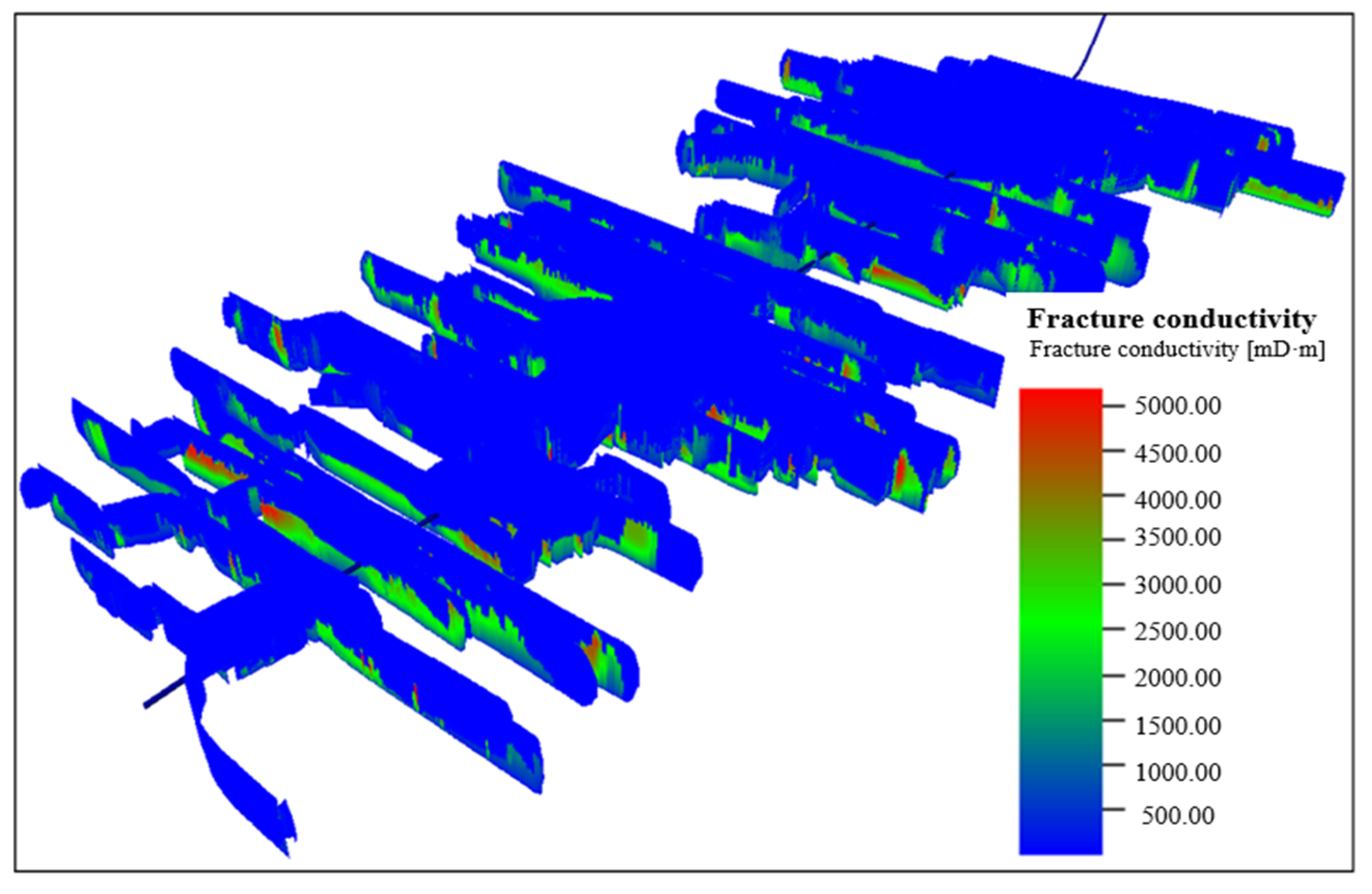

This study proposes intensive-stage fracturing technology that creatively integrates energy-replenishment pressurization with differentiated parameter design. Through numerical simulation, we investigate how different fracturing fluid volumes affect the formation pressure coefficient. We also analyze how these variations influence the estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) per well. Based on these results, the economically optimal energy-replenishment scale is evaluated by evaluating the reservoir conditions and the fracability of horizontal sections using the “dual sweet spot” approach from both geological and engineering perspectives. Based on this evaluation, targeted parameter designs—such as segment-cluster strategies, perforation techniques, and proppant-fluid volumes—are proposed. These designs guide the optimization of fracturing parameters under different reservoir conditions.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The second part describes the geological engineering conditions of ZN Oilfield in detail; the third part puts forward the reservoir transformation ideas, such as energy replenishment and pressurization process as well as differentiated parameter design for the problems faced by ZN Oilfield. The fourth part verifies the feasibility of dense cutting fracturing technology through on-site construction application. The fifth part presents the conclusions drawn from the study.