Effect of Fluidized Bed Drying on the Physicochemical, Functional, and Morpho-Structural Properties of Starch from Avocado cv. Breda By-Product

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Starch Extraction

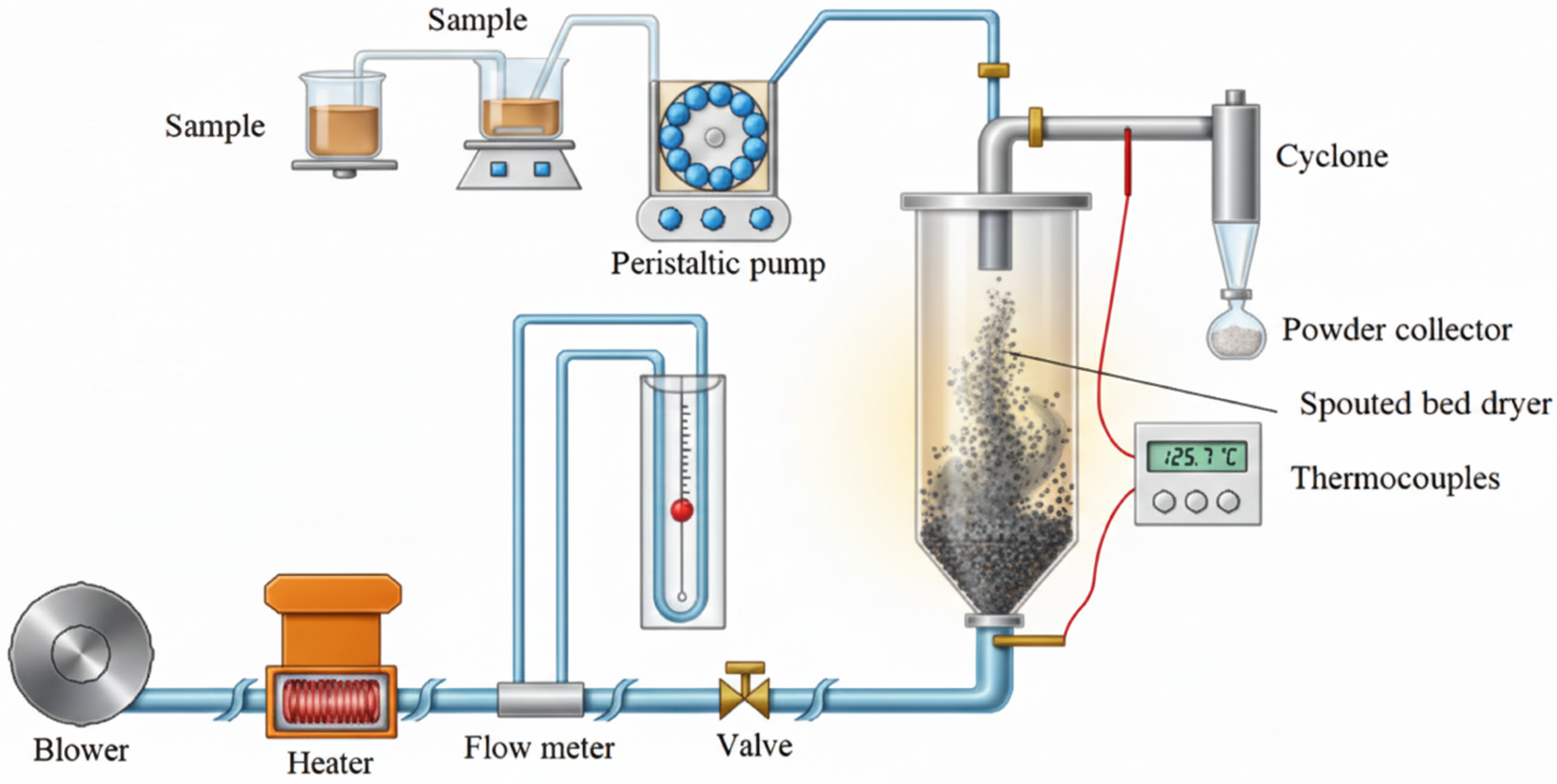

2.3. Starch Paste Drying

Sample Identification

2.4. Yield

2.5. Physical and Chemical Analyses

2.5.1. Water Content and Water Activity

2.5.2. Starch, Amylose, and Amylopectin Content

2.5.3. Water-, Oil-, and Milk-Holding Capacities

2.5.4. Swelling Power (SP) and Solubility

2.5.5. Bulk and Tapped Density

2.5.6. Hausner Ratio (HR) and Carr Index (CI)

2.5.7. Color

2.5.8. Syneresis

2.5.9. Instrumental Texture

2.6. Morphological, Structural and Thermal Properties

2.6.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.6.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.6.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

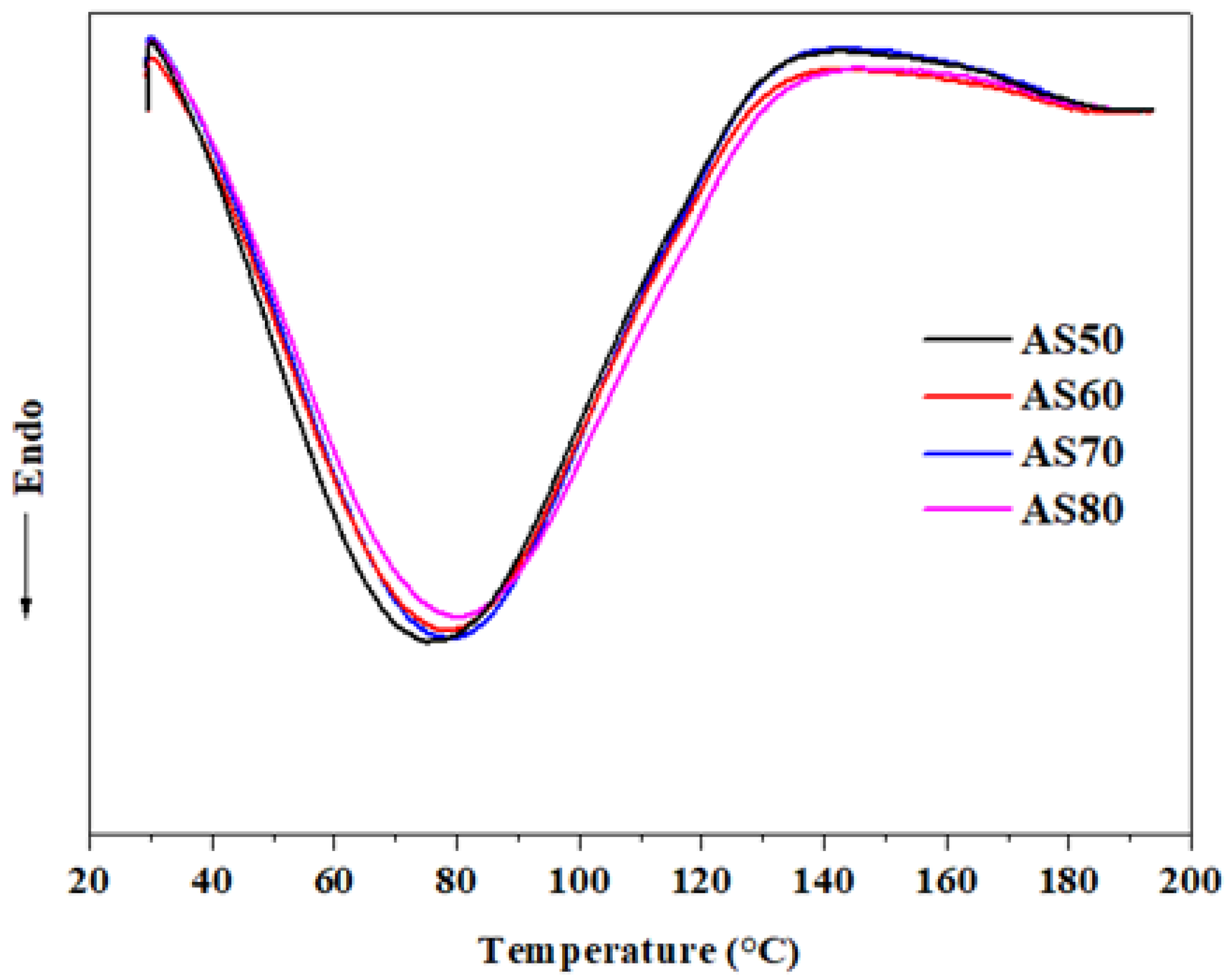

2.6.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drying Yield of the Avocado Seed Native Starch in Fluidized Bed

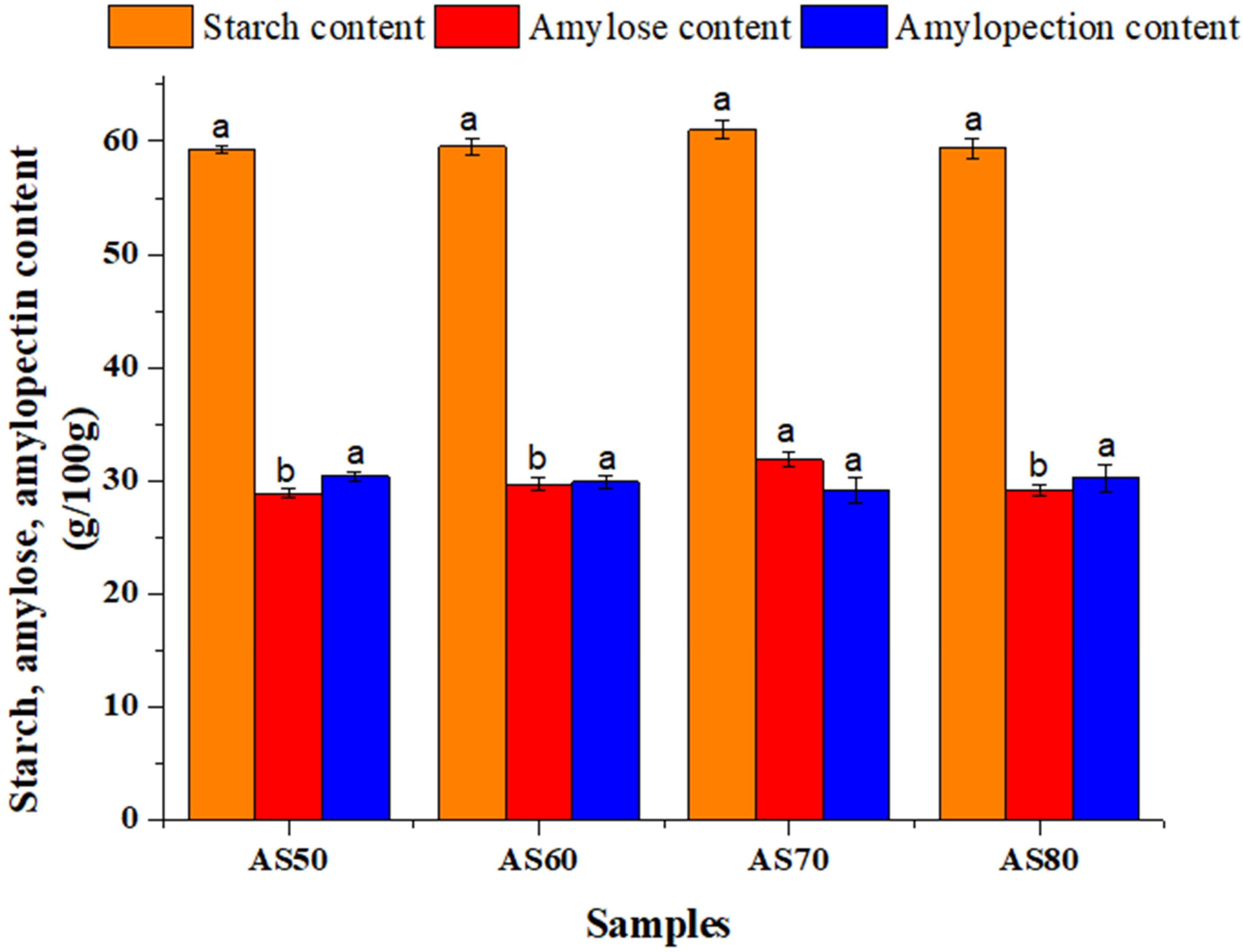

3.2. Starch, Amylose, and Amylopectin Content

3.3. Physical and Functional Properties of Avocado Seed Native Starch

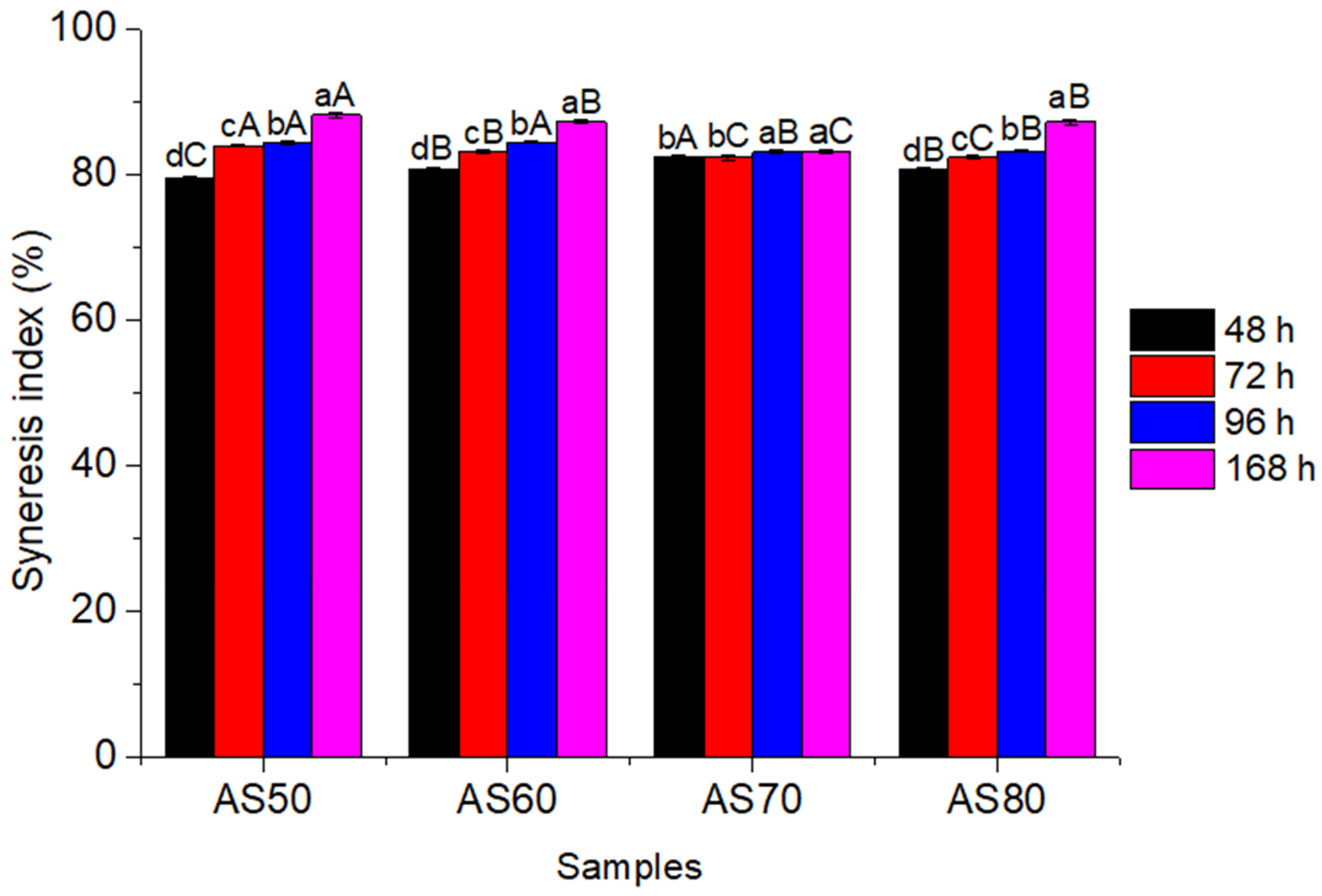

3.4. Syneresis Index

3.5. Starch Gel Texture

3.6. Morphology and Specific Surface Area

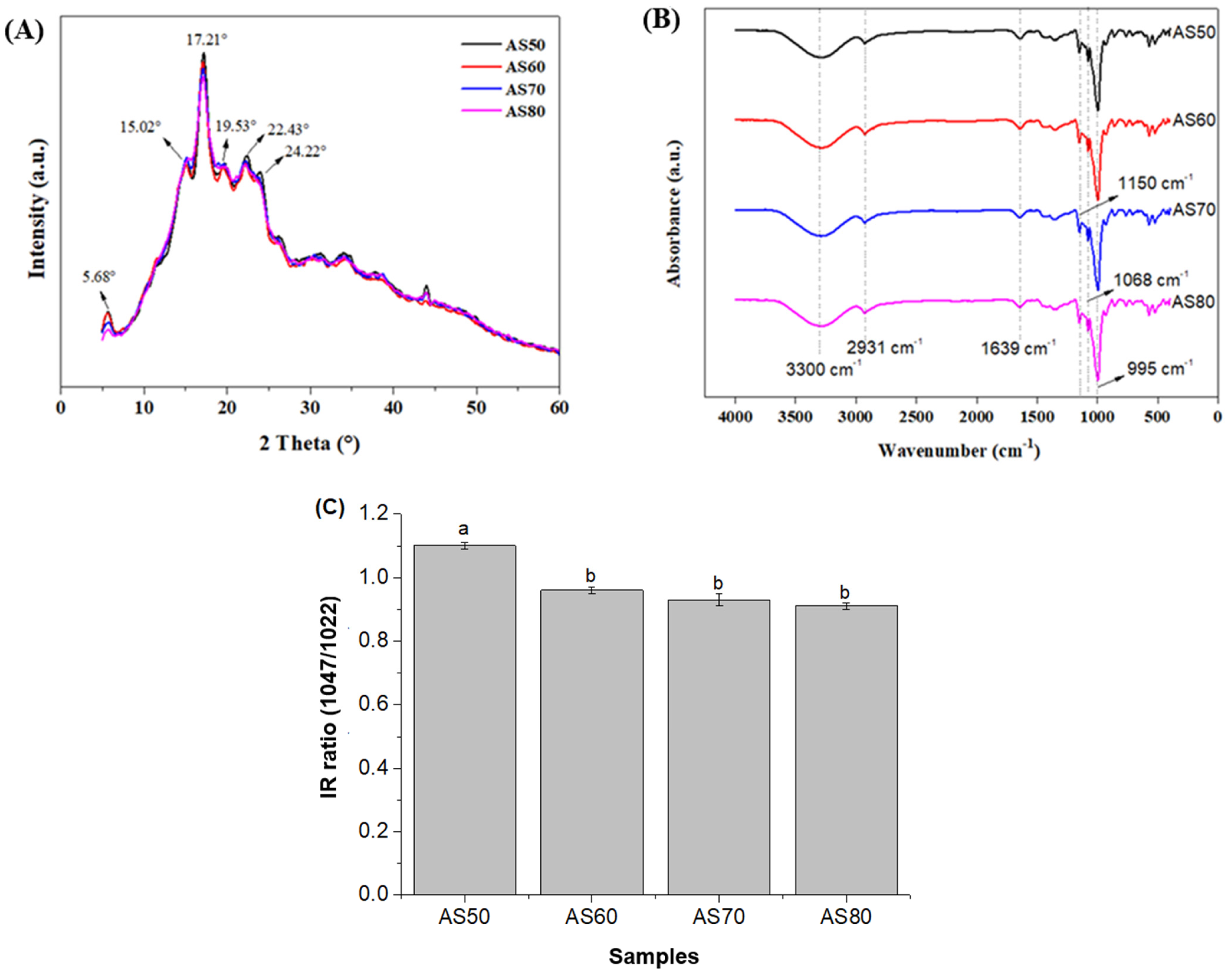

3.7. Structural Properties (XRD and FT-IR)

3.8. Thermal Properties (DSC)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, S.; Qi, Y.; Shi, L.; Giovani, M.; Zaki, N.A.A.; Guo, S.; Suleria, H.A.R. Screening of Phenolic Compounds in Rejected Avocado and Determination of Their Antioxidant Potential. Processes 2022, 10, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I.S.; Fernández, E.H.; Fernandez, J.J.G.; Hormaza, J.I.; Pedreschi, R.; Rodríguez, P.R.; González, M.F.; García, L.O.; Pancorbo, A.C. Prolonged on-tree maturation vs. cold storage of Hass avocado fruit: Changes in metabolites of bio-active interest at edible ripeness. Food Chem. 2022, 394, 133447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Quantity of Avocado Produced in 2022. IBGE Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/producao-agropecuaria/abacate/br (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Salazar-López, N.J.; Avila, J.A.D.; Yahia, E.M.; Herrera, B.H.B.; Medrano, A.W.; González, E.M.; Aguilar, G.A.G. Avocado fruit and by-products as potential sources of bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, B.G.; Mukhtar, K.; Ansar, S.; Hassan, S.A.; Hafeez, M.A.; Bhat, Z.F.; Aadil, R.M. Application of ultrasound technology for the effective management of waste from fruit and vegetable. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 102, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakirigui, A.; Ladekan, E.; Fagbohoun, L.; Sika, K.; Assogba, F.; Gbenou, J.D. Comparative phytochemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of extracts of seed and leaf of Persea americana Mill. Acad. J. Med. Plants 2020, 8, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.C.; Martín, E.B.; Antonio, A.M.; Mondragón, E.G.; Ancona, D.B. Some physicochemical and rheological properties of starch isolated from avocado seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, G.C.; Laroque, D.A.; Monteiro, A.R.; Carciofi, B.A.M.; Valencia, G.A. Current status and perspectives of starch powders modified by cold plasma: A review. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, L.; Dhull, S.B.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A. Banana starch: Properties, description, and modified variations—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.; Liu, J. Recent advances on the preparation conditions, structural characteristics, physicochemical properties, functional properties and potential applications of dialdehyde starch: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.L.J.; Santos, N.C.; Pereira, T.S.; Monteiro, S.S.; Silva, L.R.I.; Silva Eduardo, R.; Santos, E.S. Extraction and modification of Achachairu’s seed (Garcinia humilis) starch using high-intensity low-frequency ultrasound. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Araujo, T.; Souza, N.; Rodrigues, L.; Lisboa, H.M.; Pasquali, M.; Rocha, A.P. Physicochemical, morphological and antioxidant properties of spray-dried mango kernel starch. J. Agric. Food Res. 2019, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.C.; Almeida, R.L.J.; Albuquerque, J.C.; Andrade, E.W.V.; Gregório, M.G.; Santos, R.M.S.; Mota, M.M.A. Optimization of ultrasound pre-treatment and the effect of different drying techniques on antioxidant capacity, bioaccessibility, structural and thermal properties of purple cabbage. Chem. Eng. Process. 2024, 201, 109801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.G.; Andreola, K.; Mattietto, R.A.; Faria, L.J.G.; Taranto, O.P. Effect of operating conditions on the yield and quality of açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) powder produced in spouted bed. LWT 2015, 64, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, M.; Sukunza, X.; Tellabide, M.; Estiati, I.; Altzibar, H.; Arabiourrutia, M.; Olazar, M. Spout geometry of fine particle conical spouted beds equipped with internal devices. Powder Technol. 2024, 440, 119788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, M.; Tarakci, Z. Effect of grape (Vitis labrusca L.) pomace dried by different methods on physicochemical, microbiological and bioactive properties of yoghurt. LWT 2018, 97, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebowale, K.O.; Owolabi, B.I.O.; Olawumi, E.K.; Lawal, O.S. Functional properties of native, physically and chemically modified breadfruit (Artocarpus artilis) starch. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Collaboration (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 20th ed.; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Magel, E. Qualitative and quantitative determination of starch by a colorimetric method. Starch 1991, 43, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuchat, L.R. Functional and electrophoretic characteristics of succinylated peanut flour protein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1977, 25, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangsrianugul, N.; Wongsagonsup, R.; Suphantharika, M. Physicochemical and rheological properties of flour and starch from Thai pigmented rice cultivars. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparino, O.A.; Tang, J.; Nindo, C.I.; Sablani, S.S.; Powers, J.R.; Fellman, J.K. Effect of drying methods on the physical properties and microstructures of mango (Philippine ‘Carabao’ var.) powder. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Brabet, C.; Hubinger, M.D. Influência da temperatura do ar de secagem e da concentração de agente carreador sobre as propriedades físico-químicas do suco de açaí em pó. Rev. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2009, 29, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.I. Pharmaceutical Preformulation: The Physicochemical Properties of Drug Substances; E. Horwood: Chichester, UK, 1988; p. 553. [Google Scholar]

- Asokapandian, S.; Venkatachalam, S.; Swamy, G.J.; Kuppusamy, K. Optimization of foaming properties and foam mat drying of muskmelon using soy protein. J. Food Process Eng. 2016, 39, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.S.; Sulaiman, R.; Rukayadi, Y.; Ramli, S. Effect of gum Arabic concentrations on foam properties, drying kinetics and physicochemical properties of foam mat drying of cantaloupe. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 116, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, N.S.; Singh, N. Morphological, thermal and rheological properties of starches separated from rice cultivars grown in India. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, C.; Jin, Y.I.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Chang, Y.H. Structural and rheological properties of potato starch affected by degree of substitution by octenyl succinic anhydride. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 3076–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.A.; Fontes, R.L.; Fontes-Sant’Ana, G.C.; Calado, V.; López, E.O.; Rocha-Leão, M.H. Extraction, modification and characterization of starch from mango agro-industrial residue (Mangifera indica L. var. Ubá). Starch 2019, 71, 1800023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, H.; Guo, B.; Xu, K.; Dai, Q.; Wei, C.; Zhou, G.; Huo, Z. Physicochemical properties of indica–japonica hybrid rice starch from Chinese varieties. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zeng, X.; Qiu, J.; Du, J.; Cao, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Lei, T.; Liu, S.; et al. Spray-dried xylooligosaccharides carried by gum Arabic. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 135, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, P. Starch Structure, Functionality and Application in Foods; Wang, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, I.; Singh, S.; Saxena, D.C. Influence of alkali treatment on physicochemical, pasting, morphological and structural properties of mango kernel starches derived from Indian cultivars. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Li, E. Effects of amylose and amylopectin molecular structures on rheological, thermal and textural properties of soft cake batters. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrazabal, M.D.S.; Tixe, E.E.R.; Barreto, F.F.V.; Pérez, L.A.B. Avocado seed starch: Effect of the variety on molecular, physicochemical, and digestibility characteristics. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 247, 125746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Tong, Q.; Ren, F.; Zhu, G. Pasting and rheological properties of rice starch as affected by pullulan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzyk, S.; Fortuna, T.; Juszczak, L.; Galkowska, D.; Baczkowicz, M.; Łabanowska, M.; Kurdziel, M. Influence of amylose content and oxidation level of potato starch on acetylation, granule structure and radicals’ formation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosif, M.M.; Bains, A.; Sadh, P.K.; Sarangi, P.K.; Kaushik, R.; Burla, S.V.S.; Chawla, P.; Sridhar, K. Loquat seed starch—Emerging source of non-conventional starch: Structure, properties, and novel applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.; Beirão-da-Costa, M.L. Effect of drying temperature on functional and thermal properties of chestnut flours. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.J.A.; Marques, J.I.; Santos, D.D.C.; Rocha, A.P.T. Modelagem matemática da secagem de cascas de mulungu. Biosci. J. 2014, 30, 1652–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.L.J.; Pereira, T.S.; Freire, V.A.; Santiago, A.M.; Oliveira, H.M.L.; Conrado, L.S.; Gusmão, R.P. Influence of enzymatic hydrolysis on the properties of red rice starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.S.; Moreira, I.S.; Silva, L.M.M.; Lima, J.P.; Silva, W.P.; Gomes, J.P.; Figueirêdo, R.M.F. Isolation and characterization of pitomba endocarp starch. Food Res. Int. 2019, 124, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, A.K.A.M.; Millan, J.B.L.R.; Moreno, C.C.R.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Physicochemical, functional properties and digestion of isolated starches from pigmented chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars. Starch 2017, 69, 1600152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, J.O.; Duodu, K.G.; Minnaar, A. Effect of γ-irradiation on some physicochemical and thermal properties of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp) starch. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Z. Effects of moisture content on digestible fragments and molecular structures of high amylose jackfruit starch prepared by improved extrusion cooking technology. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.H.D.A.; Cavalcanti-Mata, M.E.R.M.; Almeida, R.L.J.; Silva, V.M.D.A. Characterization and Evaluation of Heat–Moisture-Modified Black and Red Rice Starch: Physicochemical, Microstructural, and Functional Properties. Foods 2023, 12, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Bian, X.; Hua, Z.; Chen, G.; Wu, X. Structural characterization and physicochemical properties of starch from four aquatic vegetable varieties in China. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 172, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterschoot, J.; Gomand, S.V.; Delcour, J.A. Impact of swelling power and granule size on pasting of blends of potato, waxy rice and maize starches. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieglar, V.; Ferreira, C.D.; Silva, J.; Zavareze, E.R.; Días, A.R.G.; Oliveira, M.; Elias, M.C. Heat-moisture treatment of oat grains and its effects on lipase activity and starch properties. Starch 2018, 70, 1700010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.C.A.; Macena, J.F.F.; Andrade, I.H.P.; Camilloto, G.P.; Cruz, R.S. Functional characterization of mango seed starch (Mangifera indica L.). Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e30310310118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, D.; Pasquali, M.A.; Cavalcanti-Mata, M.; Duarte, M.E.; Lisboa, H.M. Influence of spray drying conditions on the properties of avocado powder drink. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachuau, L.; Dutta, R.S.; Roy, P.K.; Kalita, P.; Lalhlenmawia, H. Physicochemical and disintegrant properties of glutinous rice starch of Mizoram, India. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaowiwat, N.; Madmusa, N.; Yimsuwan, K. Potential of Thai aromatic fruit (Artocarpus species) seed as an alternative natural starch for compact powder. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.K.; Luan, F.; Xu, B. Morphology, crystallinity, pasting, thermal and quality characteristics of starches from adzuki bean (Vigna angularis L.) and edible kudzu (Pueraria thomsonii Benth). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.; Rossini, C. Bioactive Natural Products from Sapindaceae: Deterrent and Toxic Metabolites Against Insects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsawatmanit, R.; Srijunthongsiri, S. Influence of xanthan gum on rheological properties and freeze–thaw stability of tapioca starch. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelti, A.L.; Teka, T.A.; Bultosa, G. Structural and physicochemical characterization of starch from water lily (Nymphaea lotus) for food and non-food applications. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, S.K.; Saravanan, A.; Narayanan, S.; Shiva, K.N.; Ravi, I.; Mayilvaganan, M.; Pushpa, R.; Uma, S. Exploring differences in the physicochemical, functional, structural, and pasting properties of banana starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Yang, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R. Effects of salts on the gelatinization and retrogradation properties of maize starch and waxy maize starch. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, S.K.; Subramaniyan, P.; Thayumanavan, S.; Shiva, K.N.; Narayanan, S.; Raman, P.; Subbaraya, U. Influence of chemical modifications on dynamic rheological behaviour, thermal techno-functionalities, morpho-structural characteristics and prebiotic activity of banana starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 126125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, N.; Sandhu, K.S.; Guraya, H.S. Physicochemical, morphological, thermal and rheological properties of starches from mango kernels. Food Chem. 2004, 85, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Lii, C.; Lai, P.; Chen, H. Water mobility, rheological and textural properties of rice starch gel. J. Cereal Sci. 2011, 53, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Rhee, C. Effect of heating condition and starch concentration on the structure and properties of freeze-dried rice starch paste. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marboh, V.; Mahanta, C.L. Rheological and textural properties of sohphlang (Flemingia vestita) starch gels as affected by heat moisture treatment and annealing. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Yao, T.; Xu, Y.; Corke, H.; Sui, Z. Pasting, thermal and rheological properties of octenylsuccinylate modified starches from diverse small granule starches differing in amylose content. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 95, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.F.M.; Li, K.B.; Xu, X.; Xie, B.J. Characters of rice starch gel modified by gellan, carrageenan, and glucomannan: A texture profile analysis study. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Sun, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Guan, X.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y. Appropriate microwave improved the texture properties of quinoa due to starch gelatinization from the destructed cyptomere structure. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, S.; Shahidi, F.; Majzoobi, M.; Koocheki, A.; Farahnaky, A. Structural, rheological, pasting and textural properties of granular cold water swelling maize starch: Effect of NaCl and CaCl2. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 242, 116406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedamulla, N.E.; Fan, M.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, E.K. Effect of pectin on printability and textural properties of potato starch 3D food printing gel during cold storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.H.; Berrios, J.D.J.; Mossman, A.P.; Takeoka, G.R.; Wood, D.F.; Mackey, B.E. Texture of jet cooked, high amylose corn starch-sucrose gels. LWT 1998, 31, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.H.F.; Pontes, K.V.; Fialho, R.L.; Fakhouri, F.M. Extraction and characterization of the starch present in the avocado seed (Persea americana mill) for future applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Sheng, Q.; Li, P.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, A.; Liu, J. The effect of heat moisture treatment times on physicochemical and digestibility properties of adzuki bean, pea, and white kidney bean flours and starches. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Oyeyinka, A.T. A review on isolation, composition, physicochemical properties and modification of Bambara groundnut starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, B.M.; Almeida, V.O.; Terstegen, T.; Hundschell, C.; Flöter, E.; Silva, F.A.; Ulbrich, M. The microstructure of the starch from the underutilized seed of jaboticaba (Plinia cauliflora). Food Chem. 2023, 423, 136145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Liang, Q.; Gao, Q. Effects of heat–moisture treatment on structural characteristics and in vitro digestibility of A-and B-type wheat starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.P.; Miranda, B.M.; Di-Medeiros, M.C.; Almeida, V.O.; Ferreira, R.D.; Morais, D.A.; Fernandes, K.F. The potential exploitation of the Malay-red apple (Syzygium malaccense) seed as source of a phosphorylated starch. Carbohydr. Res. 2024, 535, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Fajardo, E.A.; Martinez-Ascencio, E.U.; Oseguera-Toledo, M.E.; Londoño-Restrepo, S.M.; Rodriguez-García, M.E. Influence of physicochemical changes of the avocado starch throughout its pasting profile: Combined extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.L.J.; Santos, N.C.; Leite, A.C.N.; Freire, B.; Da Silva, P.N.J.; Morais, J.R.F.; Bonfim, K.S.D.; da Silva, Y.T.F.; de Melo, G.M.P.C.; Nóbrega, M.M.G.; et al. Dual modification of starch: Synergistic effects of ozonation and pulsed electric fields on structural, rheological, and functional attributes. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.L.J.; Santos, N.C.; Morais, J.R.F.; Mota, M.M.A.; Eduardo, R.S.; Muniz, C.E.S.; Cavalcante, J.A.; da Costa, G.A.; Silva, R.A.; Oliveira, B.F.; et al. Effect of freezing rates on α-amylase enzymatic susceptibility, in vitro digestibility, and technological properties of starch microparticles. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre-Gutiérrez, L.; Chel-Guerrero, L.A.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Functional properties of square banana (Musa balbisiana) starch. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Builders, P.F.; Nnurum, A.; Mbah, C.C.; Attama, A.A.; Manek, R. The physicochemical and binder properties of starch from (Persea americana Miller) (Lauraceae). Starch 2010, 62, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Cheng, Y. Physicochemical, Morphological, and Functional Properties of Starches Isolated from Avocado Seeds, a Potential Source for Resistant Starch. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Yang, W.; Zuo, Y.; Dawood, M.; He, Z. Characteristics of physicochemical properties, structure and in vitro digestibility of seed starches from five loquat cultivars. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | AS50 | AS60 | AS70 | AS80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water content (g/100 g) | 9.57 ± 0.05 a | 9.18 ± 0.0 b | 8.64 ± 0.0 c | 8.16 ± 0.0 d |

| Water activity (aw) | 0.52 ± 0.0 a | 0.49 ± 0.0 b | 0.41 ± 0.0 c | 0.36 ± 0.01 d |

| WHC (g/100 g) | 92.19 ± 0.05 a | 92.34 ± 0.01 a | 92.28 ± 0.04 a | 92.38 ± 0.01 a |

| OHC (g/100 g) | 92.21 ± 0.04 a | 92.28 ± 0.02 a | 92.21 ± 0.01 a | 92.34 ± 0.04 a |

| MHC (g/100 g) | 125.43 ± 0.04 a | 135.94 ± 0.02 a | 133.05 ± 0.04 a | 131.16 ± 0.01 a |

| Solubility (%) | 7.42 ± 0.75 ab | 8.35 ± 1.41 a | 5.22 ± 0.33 bc | 4.51 ± 0.83 c |

| SP (g/100 g) | 57.10 ± 1.95 a | 57.39 ± 2.57 a | 58.13 ± 4.45 a | 56.25 ± 4.06 a |

| Bulk density (g/cm3) | 0.58 ± 0.03 a | 0.56 ± 0.05 a | 0.54 ± 0.01 a | 0.56 ± 0.01 a |

| Tapped density (g/cm3) | 0.67 ± 0.02 ab | 0.65 ± 0.02 b | 0.70 ± 0.01 a | 0.67 ± 0.0 ab |

| Carr index (CI) (%) | 13.20 ± 0.04 b | 14.20 ± 0.05 ab | 22.50 ± 0.02 a | 15.90 ± 0.01 ab |

| Hausner ratio (HR) | 1.15 ± 0.05 b | 1.16 ± 0.08 ab | 1.29 ± 0.03 a | 1.18 ± 0.02 ab |

| L* | 45.39 ± 0.0 c | 51.93 ± 0.07 a | 42.46 ± 0.10 d | 46.92 ± 0.02 b |

| a* | 3.12 ± 0.01 a | 2.70 ± 0.01 c | 2.49 ± 0.03 d | 2.94 ± 0.03 b |

| b* | 6.11 ± 0.01 a | 5.79 ± 0.02 c | 4.96 ± 0.02 d | 5.98 ± 0.02 b |

| Parameters | AS50 | AS60 | AS70 | AS80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firmness (N) | 2.63 ± 0.18 a | 2.37 ± 0.16 a | 2.75 ± 0.61 a | 3.89 ± 0.26 a |

| Elasticity | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 1.00 ± 0.00 a | 1.00 ± 0.00 a |

| Cohesiveness (N) | 0.51 ± 0.07 a | 0.52 ± 0.00 a | 0.54 ± 0.05 a | 0.54 ± 0.04 a |

| Adhesiveness (N·m) | 0.85 ± 0.16 a | 1.34 ± 0.14 a | 1.32 ± 0.10 a | 1.27 ± 0.29 a |

| Gumminess (N) | 1.34 ± 0.10 a | 1.23 ± 0.10 a | 1.48 ± 0.17 a | 1.28 ± 0.04 a |

| Diameter (µm) | 101.67 ± 8.76 a | 108.54 ± 11.48 a | 130.68 ± 6.40 a | 117.23 ± 9.34 a |

| RC (%) | 24.27 ± 0.44 a | 23.84 ± 0.37 a | 23.55 ± 0.52 a | 23.29 ± 0.43 a |

| To (°C) | 30.01 ± 0.02 d | 30.34 ± 0.01 c | 31.39 ± 0.05 b | 31.73 ± 0.04 a |

| Tp (°C) | 75.78 ± 0.15 d | 78.23 ± 0.18 c | 78.90 ± 0.10 b | 79.56 ± 0.11 a |

| Tc (°C) | 134.05 ± 0.22 c | 135.11 ± 0.11 b | 136.84 ± 0.14 a | 137.17 ± 0.19 a |

| ΔH (J/g) | 14.18 ± 0.16 d | 14.66 ± 0.21 c | 15.04 ± 0.12 b | 15.49 ± 0.18 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tomé, A.E.S.; Camilo, Y.B.; Santos, N.C.; Rosendo, P.P.D.; de Oliveira, E.A.; Matias, J.G.; Morais, S.K.Q.; Gusmão, T.A.S.; Gusmão, R.P.d.; Gomes, J.P.; et al. Effect of Fluidized Bed Drying on the Physicochemical, Functional, and Morpho-Structural Properties of Starch from Avocado cv. Breda By-Product. Processes 2026, 14, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010122

Tomé AES, Camilo YB, Santos NC, Rosendo PPD, de Oliveira EA, Matias JG, Morais SKQ, Gusmão TAS, Gusmão RPd, Gomes JP, et al. Effect of Fluidized Bed Drying on the Physicochemical, Functional, and Morpho-Structural Properties of Starch from Avocado cv. Breda By-Product. Processes. 2026; 14(1):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomé, Anna Emanuelle S., Yann B. Camilo, Newton Carlos Santos, Priscylla P. D. Rosendo, Elizabeth A. de Oliveira, Jéssica G. Matias, Sinthya K. Q. Morais, Thaisa A. S. Gusmão, Rennan P. de Gusmão, Josivanda P. Gomes, and et al. 2026. "Effect of Fluidized Bed Drying on the Physicochemical, Functional, and Morpho-Structural Properties of Starch from Avocado cv. Breda By-Product" Processes 14, no. 1: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010122

APA StyleTomé, A. E. S., Camilo, Y. B., Santos, N. C., Rosendo, P. P. D., de Oliveira, E. A., Matias, J. G., Morais, S. K. Q., Gusmão, T. A. S., Gusmão, R. P. d., Gomes, J. P., & Rocha, A. P. T. (2026). Effect of Fluidized Bed Drying on the Physicochemical, Functional, and Morpho-Structural Properties of Starch from Avocado cv. Breda By-Product. Processes, 14(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010122