1. Introduction

Heavy oil, a critical unconventional oil resource, is pivotal for ensuring energy security [

1,

2]. However, its inherent properties—high viscosity, elevated resin and asphaltene contents, and poor fluidity—pose significant challenges to conventional recovery technologies, resulting in low recovery efficiency, high energy consumption, and increased costs [

3,

4]. In-situ combustion (ISC) [

5,

6,

7], a promising thermal recovery technology, involves igniting crude oil in situ to establish a stable combustion front. By utilizing heat generated from combustion to reduce viscosity and gas displacement to enhance mobility, ISC significantly improves oil recovery and has been successfully applied in industrial-scale operations globally, demonstrating remarkable technical merits and broad application prospects [

8,

9].

During fire flooding, coke [

10,

11] serves as the primary fuel sustaining continuous ISC. Its formation characteristics and physicochemical properties directly influence the success of fire flooding development [

12]: on the one hand, heat released from coke combustion provides energy for reducing oil viscosity and propagating the combustion front, where combustion efficiency affects front velocity, temperature distribution, and sweep efficiency [

13]; on the other hand, key coke properties (e.g., pore structure, specific surface area, oxidation activity) modulate oxygen diffusion efficiency and reaction kinetics [

14]. Additionally, coke deposition and spatial distribution may cause reservoir pore blockage and alter formation permeability, thereby impairing displacement efficiency and oil recovery [

15]. Systematic investigations into the mechanisms and characteristic patterns of coke formation are therefore of profound theoretical and engineering significance for optimizing fire flooding parameters, regulating combustion processes, and enhancing recovery efficiency [

16].

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on fire flooding coke worldwide. The formation mechanisms [

17] of coke have been explored using techniques such as thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) [

18], Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) [

19], and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [

20]. These methods have elucidated the cracking–polymerization–oxidation pathways of resins and asphaltenes under varying temperatures and oxygen concentrations, thereby clarifying the effects of crude oil components and reaction conditions on coke yield [

21]. For physicochemical characterization, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [

22], X-ray diffraction (XRD) [

23], and BET analysis have been employed to investigate the microstructure, crystal structure, pore features, and elemental composition of the coke [

16,

24]. This has established correlations between its physical properties and combustion activity. However, most studies focus on coke derived from a single type of heavy oil [

25,

26,

27], lacking comparative investigations on cokes derived from oils with distinct properties. Given the significant differences in heavy oil properties (e.g., viscosity, resin/asphaltene content, wax content), their thermal conversion behaviors during fire flooding inherently vary, leading to notable discrepancies in the formation mechanisms, physicochemical properties, and combustion characteristics of the resulting coke. Currently, the intrinsic mechanisms, influencing factors, and engineering value of these differences remain inadequately understood, failing to meet the demands for precise regulation of fire flooding in complex heavy oil reservoirs.

To bridge this knowledge gap, the present study examines two heavy oils with distinct characteristics: paraffin-based oil sourced from Menggulin Oilfield [

28] and naphthenic-based oil from Xinjiang Oilfield [

29]. By delving into the composition of these crude oils, we elucidate disparities in their coking processes. Utilizing laboratory simulations to replicate thermal reactions for coke preparation and employing a suite of advanced analytical techniques, we provide an exhaustive characterization of variations in coke yield, microstructure, chemical composition, crystal structure, and combustion activity under diverse temperatures and oxidative atmospheres. This investigation not only augments the foundational understanding of solid product formation during fire flooding but also furnishes fresh perspectives to address engineering challenges in the development of intricate heavy oil reservoirs, thereby holding significant academic merit and practical applicability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oxidation Process of the Crude Oil

Petroleum coke was synthesized by a static oxidation method using a low-pressure kettle furnace [

30], with the experimental design grounded in the free radical chain reaction theory of hydrocarbon oxidation; this mechanism assumes that oxygen molecules initiate the cleavage of C–H bonds in crude oil hydrocarbons to form alkyl free radicals, which subsequently undergo chain propagation and termination to generate coke precursors.

In a typical procedure, 30 g of crude oil was charged into the furnace, and a gas mixture (21% O2 + 79% N2, simulating atmospheric oxygen partial pressure) was introduced directly into the crude oil at a flow rate of 100 mL/min; this gas flow rate was numerically calibrated to ensure an oxygen-to-crude oil molar ratio of ~0.08, sufficient to drive moderate oxidation without excessive combustion. A thermocouple inserted from the top of the autoclave continuously monitored the internal temperature of the crude oil, while the system pressure was maintained at 0.1 MPa. The coking process followed a programmed temperature protocol: heating at 5 °C/min to a set temperature of either 350 °C or 450 °C (simulating the geothermal gradient-driven temperature rise in reservoir rocks), holding at that temperature for 60 min (to allow sufficient time for oxidation-induced cross-linking reactions), and then stopping heating to allow the system to cool naturally to room temperature. After cooling, the autoclave was opened to retrieve the solid products.

The resulting solids were dissolved and washed with trichloroethylene to remove unreacted saturates, aromatics, and resins. The insoluble residues remaining after trichloroethylene treatment were collected, and petroleum coke was obtained by evaporating the solvent to dryness.

2.2. Characterization of Oil Samples

The SARA components of the crude oil were analyzed according to China Petroleum Industry Standard SY/T 5119-2016.

The crude oil samples were analyzed using an Agilent 7890B-5977A gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system equipped with a VF-5ht MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.1 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). High-purity helium was used as the carrier gas. The oven temperature program started at 35 °C, increased to 320 °C at 5 °C min−1 and was held for 5 min at 320 °C. The injector temperature was maintained at 320 °C, and the mass spectrometer interface temperature was set at 250 °C. The flow rate of the carrier gas was controlled at 1 mL min−1. Before analysis, the oil samples were dissolved in dichloromethane to yield a concentration of 100 mgL−1, and the injection volume was 1.0 μL at a split ratio of 20:1.

2.3. Characterization of Cokes

FTIR spectra were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (VERTEX 70, Bruker Technologies Ltd., Billerica, MA, USA). The characteristics of the petroleum coke were determined using 13C solid-state NMR carbon spectroscopy (AvanceIII 400 MHz, Bruker Technologies Ltd.) and a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-6701F, Tokyo, Japan).

Furthermore, an STA449F3 synchronous thermal analyzer (NETZSCH, Waldkraiburg, Germany) was used to characterize the mass loss, combustion temperature, and exothermic behavior of petroleum coke in an air atmosphere.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composition Characteristics of Crude Oil

Table 1 summarizes the SARA fraction compositions and viscosity at 50 °C (mPa·s) of the two crude oil samples. Menggulin oil (sampling date: January 2024) contained 43.78 wt% saturates, 13.81 wt% aromatics, 37.46 wt% resins, and 4.90 wt% asphaltenes with a viscosity of 221 mPa·s at 50 °C. In contrast, Xinjiang oil (sampling date: February 2024) exhibited a higher saturate content (52.68 wt%) but lower contents of aromatics (12.40 wt%), resin (32.79 wt%), and asphaltene (2.13 wt%) along with a significantly higher viscosity of 884 mPa·s at 50 °C.

Table 2 presents the elemental composition of the two types of crude oil. The two crude oils exhibit similar carbon and hydrogen contents, with Menggulin oil having a slightly higher H/C atomic ratio (1.76). This characteristic is consistent with the compositional properties of paraffin-based crude oil, as Menggulin oil is enriched in linear/branched alkanes (saturated fractions). In contrast, Xinjiang oil contains more heteroatoms (i.e., oxygen 1.53%, nitrogen 0.22%, and sulfur 0.10%) and is abundant in cyclic hydrocarbons (naphthenes and aromatics), featuring condensed structures.

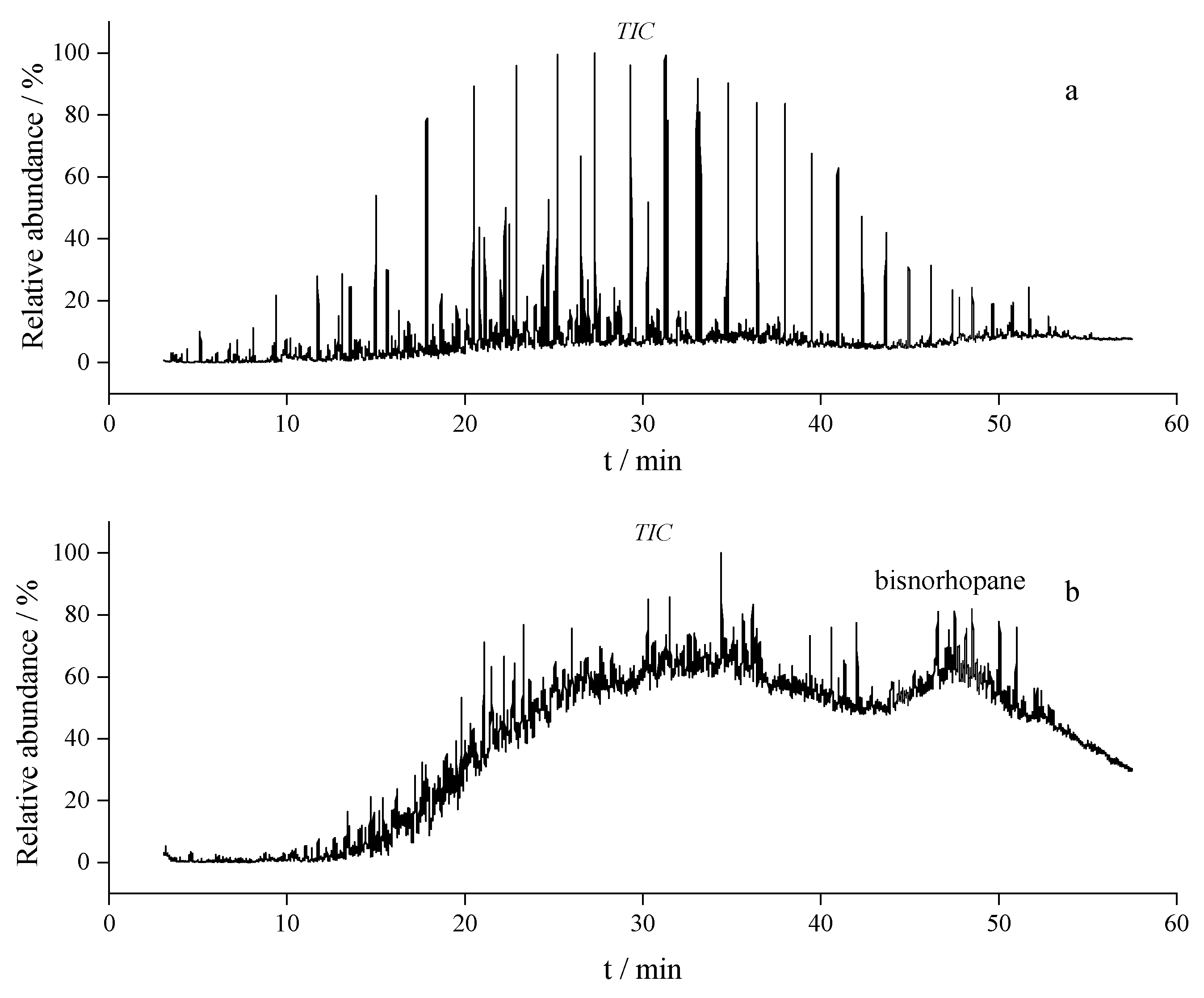

Figure 1 shows the total ion chromatograms (TICs) of Menggulin oil (

Figure 1a) and Xinjiang oil (

Figure 1b) from GC-MS analysis, with retention time (t

R, min) on abscissa and relative abundance (%) on ordinate.

Menggulin crude oil was sampled from non-responding wells in its fire flooding test zone. The reservoir is conglomerate-dominated, heterogeneous with medium porosity and medium-high permeability, and has an average burial depth of 800 m, in-situ temperature of 37.2 °C and pressure of 7.58 MPa. As a paraffin-based crude enriched in linear/branched alkanes, Menggulin oil has a concentrated peak distribution in its TIC: within the tR range of 4–60 min, peaks are densely clustered at ~30 min to form a high-abundance peak cluster. This pattern is consistent with the compositional characteristics of paraffin-based crudes—their alkane-dominated saturate fraction elutes within a narrow retention window during GC separation. In contrast, few low-abundance peaks occur in other regions (e.g., tR < 10 min or tR > 40 min).

Xinjiang crude oil was sampled from non-responding wells in the Hongqian fire flooding test zone. The Badaowan Formation reservoir consists of glutenite with medium-high porosity and permeability, with an average burial depth of 550 m, in-situ temperature of 23.9 °C and pressure of 6.41 MPa. Xinjiang oil, as a naphthenic-based crude rich in naphthenes and structurally diverse cyclic hydrocarbons, displays more dispersed TIC. Its peak number gradually increases after ~10 min, forming continuous high-abundance cluster at 20–40 min, with multiple distinguishable peaks persisting beyond 40 min. Such a broad peak distribution reflects the complex composition of naphthenic-based crudes: cyclic hydrocarbons (with variable ring numbers and substituents) exhibit more dispersed retention behaviors during GC separation, resulting in a less concentrated peak profile compared to paraffin-based Menggulin oil.

3.2. Yield of Coke from Two Types of Crude Oil

ISC can elevate reservoir temperatures to exceed 600 °C. As the combustion front propagates, it triggers a series of reactions in the reservoir: low-temperature oxidation [LTO], high-temperature oxidation [HTO], and high-temperature pyrolysis. Notably, temperature plays a pivotal role in coke formation. The primary emphasis of ISC is on medium-temperature oxidation (MTO, 200–400 °C) and high-temperature pyrolysis (400–500 °C). Coke yields of the two crude oils were comparatively evaluated at 350 °C and 450 °C (refer to

Table 3). The coke yield data presented in

Table 3 are the mean values derived from triplicate experiments, which were conducted under identical heating, airflow and oxidation conditions to minimize random errors.

As temperature increased from 350 °C to 450 °C, the average coke yield of Menggulin crude oil rose sharply by 97%, from 7.61 wt% to 14.99 wt%. This underscores its pronounced temperature dependence, encapsulated by the phrase “high temperature promoting coke formation”. Conversely, the coke yield of Xinjiang crude oil showed a moderate increase, rising from an average of 8.22 wt% at 350 °C to 10.83 wt% at 450 °C, corresponding to a growth rate of merely 32%. It is distinguished as “significant coke production at medium temperatures but constrained potential at elevated temperatures”.

Naphthenic-based Xinjiang oil has a higher coke yield at 350 °C, which is mainly due to the synergistic effect of its cyclic hydrocarbon structure and high heteroatom content. The naphthenes and aromatics are rich in ring hydrogen atoms with low bond energy through ring conjugation, making them prone to dehydrogenation and condensation under medium temperature oxidation. In particular, the cyclic structures undergo side chain breaking and cyclodehydrogenation to form polycyclic aromatic substances that aggregate into coke precursors (asphaltene-like substances) and eventually turn into coke. It should be noted that the O (1.53 wt%), N (0.22 wt%) and S (0.10 wt%) contents of Xinjiang oil are higher than those of Menggulin oil (0.75 wt%, 0.1 wt% and 0.07 wt%). The oxygen-containing heteroatoms (in the form of C–O and C–O–C moieties) [

31] may serve as potential “active sites” that could facilitate the cross-linking/polymerization of cyclic molecules, potentially lowering the activation energy for condensation reactions and weakly promoting coke formation.

Paraffin-based Menggulin oil has a lower coke yield at 350 °C because it is limited by the reaction path of linear/branched alkanes. Dominated by saturated alkanes (43.78 wt% in SARA saturates), alkanes undergo low-to-medium temperature oxidation (such as peroxide/carboxylic acid generation) rather than cracking polymerization at 350 °C. Its linear structure and lack of ring conjugation require higher energy for C-C bond breaking, resulting in fewer olefins or small-molecule active intermediates, weaker polymerization, and lower coke yield. At 350 °C, Xinjiang crude oil forms more coke earlier than Menggulin oil, providing early “fuel” for the combustion front and stabilizing initial combustion.

The temperature of 450 °C serves as a critical threshold for alkane cracking, triggering a significant increase in the coke yield of Menggulin oil through intensive alkane cracking–polymerization. At this specific temperature, both linear and branched alkanes within Menggulin oil undergo profound cracking, producing an abundance of small-molecule olefins and alkyl radicals. These reactive intermediates quickly engage in chain growth, cyclization, and dehydrogenative polymerization, leading to the formation of polycyclic aromatics and ultimately, coke. This increases the average coke yield from 7.61 wt% to 14.99 wt%. The rapid formation of coke facilitates continuous fuel replenishment, sustaining high-temperature combustion following front propagation. Conversely, Xinjiang oil’s coking potential is partially depleted at medium temperatures, necessitating reliance on pre-formed coke to maintain high-temperature combustion.

In the context of fire flooding optimization, it is imperative to customize gas injection parameters such as oxygen concentration and heating rate in accordance with the type of crude oil. For paraffin-based oils, it is crucial to ensure an adequate energy supply during high-temperature pyrolysis to facilitate coke formation. Conversely, for naphthenic-based oils, it is essential to regulate medium-temperature oxidation to augment initial coke accumulation, thereby ensuring stable propagation of the combustion front.

3.3. Microstructural Morphology Characteristics of Cokes

Figure 2 shows the microstructure differences of cokes from pyrolysis of Menggulin and Xinjiang crude oils at 350 °C and 450 °C.

Figure 2a (Menggulin Oil, 350 °C) shows a coarse surface particle accumulation in the main structure. Morphologically, it exhibits scattered small fragments (2–5 μm) with weak interparticle adhesion, loose structure and negligible porosity.

Figure 2b (Menggulin oil, 450 °C) consists of large agglomerates (>20 μm diameter) with 1–3 μm pores and wrinkled surfaces, which significantly enhances the structural compactness.

Figure 2c (Xinjiang oil, 350 °C) presents dense and well-defined sheet/block-like aggregates (~1–2 μm thick) with few fine particles adhering to the surface and sharp edge contours.

Figure 2d (Xinjiang oil, 450 °C) comprises densely packed fine particles characterized by high surface roughness and distinct stacking gaps; moreover, clear layered textures (~0.5 μm spacing) are observed on the cross-section.

These morphological differences stem from the composition-driven variations in pyrolysis pathways, which are temperature dependent. At 350 °C (mild pyrolysis), the reaction is dominated by initial resin condensation. The Menggulin oil, with low resin/asphaltene content and high saturated hydrocarbons, undergoes insufficient intermolecular condensation and weak interaction, resulting in loosely structured coke fragments. In contrast, the Xinjiang oil rich in resin/asphaltene and aromatic rings undergoes π–π stacking and mild crosslinking of aromatic groups at 350 °C, facilitating strong intermolecular adhesion and dense sheet/block-like structures. At 450 °C (deep pyrolysis), the reaction shifts to aromatic ring condensation and asphaltene crosslinking. The abundant long chain structures in the Menggulin oil undergo intense cracking, generating internal pores within agglomerates; linear stacking-dominated polymerization eventually forms large and dense agglomerates. In contrast, the naphthenic structures in the Xinjiang oil impart enhanced structural stability, leading to minimal internal coke cracking and no distinct porosity development. The cross-sectional layered texture is characteristic of oriented resin/asphaltene stacking, which is more pronounced in oils with higher resin contents due to the ordered arrangement of stacked molecules.

3.4. Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of Cokes

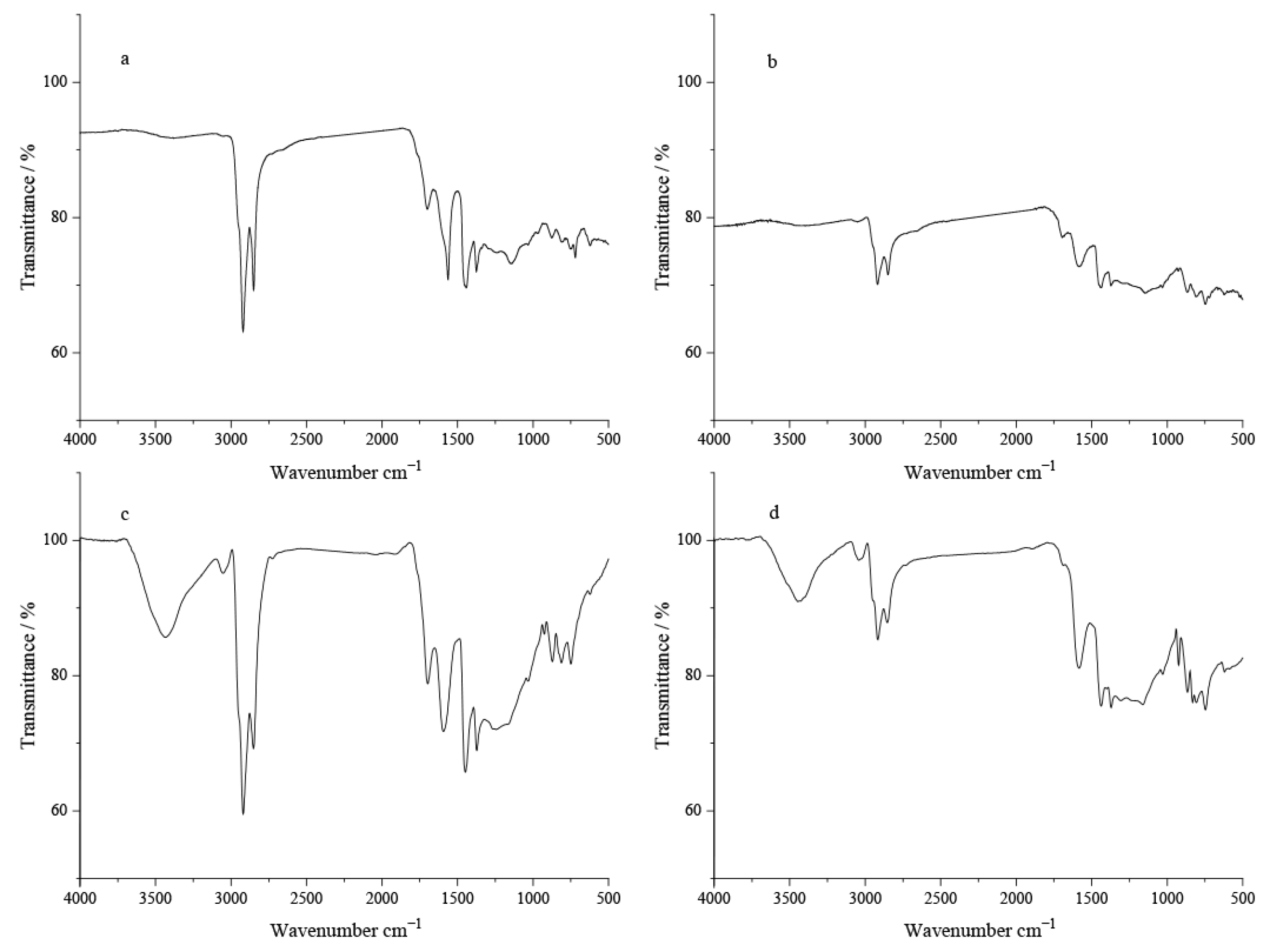

The IR spectroscopic characteristics of cokes from Menggulin and Xinjiang crude oils at 350 °C and 450 °C indicate that temperature is the key factor controlling the coking behavior of a given crude oil. Coke a (

Figure 3a) from Menggulin crude oil at 350 °C was formed by an oxidation-dominated coking process due to the relatively low reaction temperature: its infrared (IR) spectrum exhibits strong absorption peaks at 1600–1700 cm

−1 (relative intensity 22%, assigned to C=O stretching and aromatic C=C vibration) and 1100 cm

−1 (relative intensity 21%, corresponding to C–O stretching), indicating a high abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups. Coke b (

Figure 3b) from Menggulin crude oil at 450 °C underwent a deep pyrolysis-dominated coking process under higher temperature conditions: extensive breaking of alkyl C–H bonds occurred, as evidenced by very weak absorption at 2800–3000 cm

−1 (relative intensity 8%, alkyl C–H stretching), while the oxidation action was significantly suppressed. This promoted the condensation of aromatics, resulting in a pyrolytic coke with a simple structure and few oxygenated functional groups. Coke c (

Figure 3c) from Xinjiang crude oil at 350 °C exhibited moderate pyrolysis, relatively strong absorption at 2800–3000 cm

−1 (relative intensity 40%, residual alkyl C–H stretching) and prominent absorption peaks at 1600–1700 cm

−1 (relative intensity 30%) and 1100 cm

−1 (relative intensity 29%) further confirm its oxidized coke characteristics. For Coke d (

Figure 3d) from Xinjiang crude oil at 450 °C, the increased temperature enhanced the breaking of alkyl C–H bonds during pyrolysis, as evidenced by the relatively low relative intensity (16%) at 2800–3000 cm

−1; however, the oxidation and pyrolysis processes were synergistically balanced, leading to comparable contributions from oxygenated functional groups and aromatic structures.

Coking disparities at identical temperatures reflect the impact of inherent crude composition. At 350 °C, the oxidation-dominated character of Coke a (Menggulin Crude) contrasts sharply with the alkane-rich nature of Coke c (Xinjiang Crude), suggesting that Xinjiang crude possesses a higher proportion of long-chain alkanes, which increases pyrolytic bond scission difficulty. At 450 °C, the deep pyrolysis (oxidation-suppressed) character of Coke b (Menggulin Crude) differs markedly from the oxygenated functional group retention behavior of Coke d (Xinjiang Crude), implying that the molecular architecture of Xinjiang Crude is more prone to oxidation reactions. Fundamentally, these coking disparities arise from the synergistic interplay between crude composition and pyrolysis–oxidation conditions; the resulting functional group distribution and structural properties of the coke will directly govern its combustion reactivity and compatibility with reservoir pore networks during fire flooding operations.

3.5. Analysis of 13C Solid-State NMR Characteristics of Cokes

The high carbon content of the coke (>80%) originates from the decomposition and release of light hydrocarbon fractions, which leaves the thermally stable resins and asphaltenes to undergo cross-linking and aromatization, thereby forming the coke matrix. As a high-resolution and non-destructive technique for the characterization of carbon species,

13C solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (

13C ss-NMR) allows for comprehensive profiling of the distribution of carbon atoms in the coke matrix. The chemical shifts in the

13C ss-NMR spectra correspond to different structural carbon motifs [

20]: 0–50 ppm: Aliphatic carbons, including saturated alkyl units such as methyl and methylene groups; 50–100 ppm: Heteroaliphatic/oxygenated aliphatic carbons, e.g., C–O bonded carbons, C–O–C bonded carbons; 100–160 ppm: Aromatic carbons, i.e., aromatic ring skeleton units; 160–220 ppm: Carbonyl/carboxyl carbons, i.e., functional groups derived from oxidation.

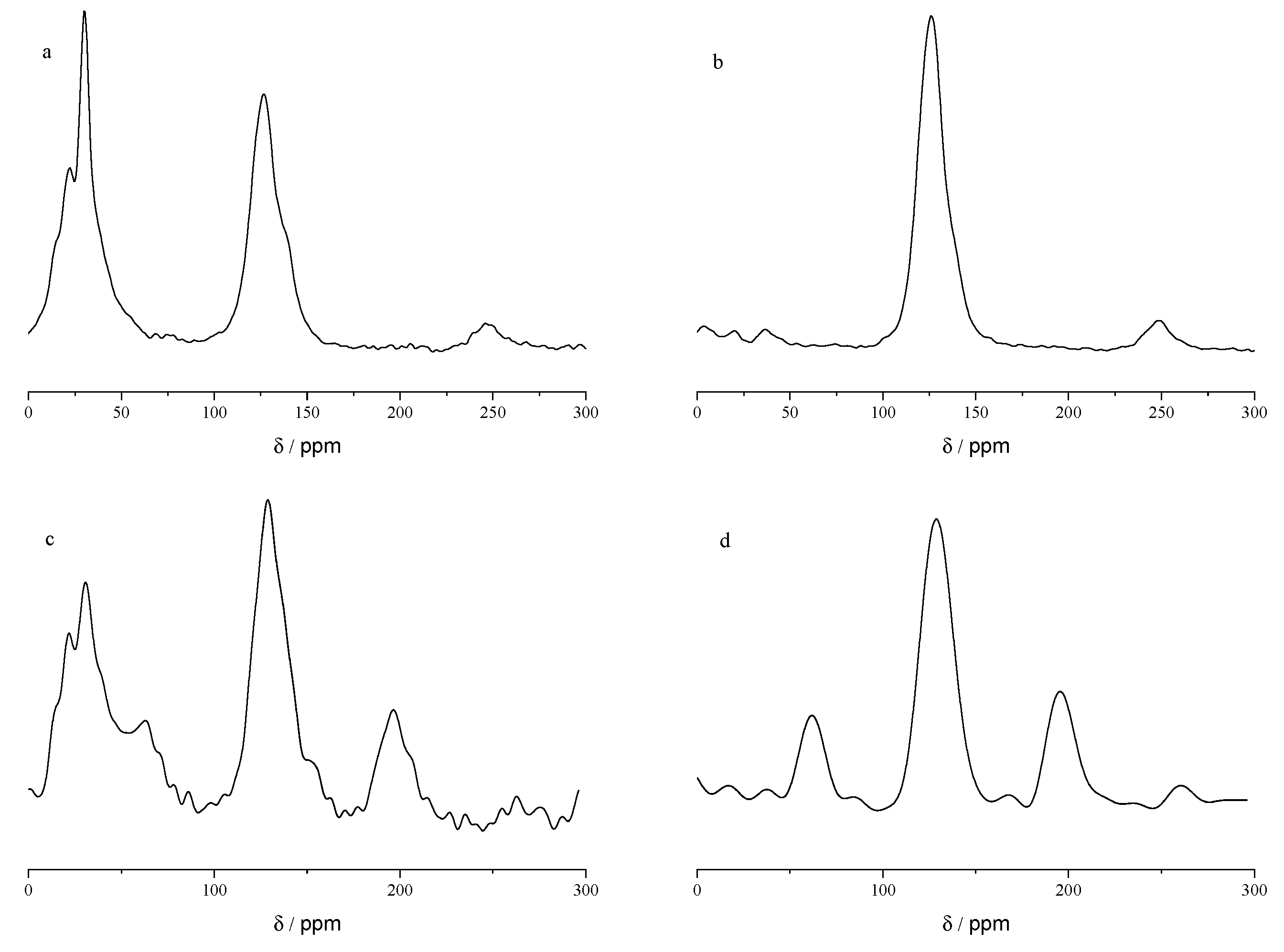

Figure 4 shows the

13C ss-NMR spectra of these four cokes.

For Menggulin crude oil, increasing the coking temperature from 350 to 450 °C significantly promoted the cleavage of aliphatic carbon (0–50 ppm), the peak area proportion of this region decreased sharply from ~28% to ~4% (evidenced by signal attenuation from distinct residual to extremely weak). Meanwhile, higher temperatures enhanced aromatic carbon (100–160 ppm) condensation and enrichment, with its peak area proportion increasing from ~52% to ~89%; concurrently, oxidative reactions under high-temperature conditions were suppressed, as the peak area of oxygenated carbon (50–100 ppm) dropped from ~15% to <1%, and carbonyl carbon (160–220 ppm) disappeared entirely (from ~5% to 0%).

In contrast, for Xinjiang crude oil, although increasing temperature also weakened the aliphatic carbon signal (0–50 ppm), its peak area proportion only decreased from ~35% to ~12% (residual aliphatic carbon was not completely eliminated). Furthermore, the oxidative activity was not effectively inhibited: the peak area proportion of oxygenated carbon (50–100 ppm, encompassing both C–O and C–O–C bonded structures) remained at ~10% (compared to ~18% at 350 °C), and carbonyl carbon (160–220 ppm) still accounted for ~3% (slightly down from ~6% at 350 °C). The persistent presence of these oxygen-containing moieties implies that heteroatom-mediated cross-linking may occur within the coke matrix during pyrolysis. Specifically, the C–O–C structures could act as potential bridging units between hydrocarbon fragments, which might facilitate the formation of relatively stable cross-linked networks and thus impede the complete elimination of oxygenated species even at elevated temperatures of 450 °C. This suggests that temperature has different regulatory effects on oxidative behavior during the coking process for different types of crude oil feedstock.

The inherent chemical composition of crude oil predominantly influences the carbon structure of its resultant coke. Variations in coking at identical temperatures directly mirror the fundamental compositional characteristics of the source oils. At 350 °C, Xinjiang crude oil-derived coke possesses a notably higher residual aliphatic carbon content (0–50 ppm, ~35% peak area) than that derived from Menggulin crude oil (~28% peak area), while Menggulin coke has a comparatively lower aromatic carbon condensation degree (100–160 ppm, ~52% vs. ~48% peak area for Xinjiang coke). By contrast, at 450 °C, Menggulin crude oil-derived coke demonstrates pronounced aromatization (aromatic carbon: ~89% peak area) and minimal heteroatom presence (oxygenated carbon: <1%), whereas Xinjiang crude oil-derived coke retains oxygenated carbons (~10% peak area) and displays a multifaceted aromatic carbon peak profile (aromatic carbon: ~75% peak area). This disparity primarily arises due to the increased propensity of Xinjiang crude oil’s molecular configuration towards oxidative reactions. Such variations in carbon structures are direct outcomes of the interplay between crude oil composition and pyrolysis–oxidation conditions, establishing a foundational framework for ensuing correlations between coke combustion reactivity and reservoir compatibility.

3.6. Analysis of TG-DSC Spectrum of Cokes

TG-DSC can simultaneously obtain thermal weight loss and reaction enthalpy change information. The combustion behavior of coke under air atmosphere is related to three key parameters: the weightlessness interval, exothermic characteristics, and carbon structural units. Specifically, the low temperature zone (200–400 °C) corresponds to the oxidation of oxygen-containing functional groups and aliphatic carbons, while the high temperature zone (400–600 °C) corresponds to the oxidation of condensed aromatic carbon structures. The combustion reactivity (characterized by the exothermic peak temperature) and heat release (characterized by the peak area) are jointly determined by the synergistic effect of pyrolysis and oxidation during carbonization and the inherent chemical composition of the original crude oil.

Figure 5 shows the TG-DSC curves of Menggulin and Xinjiang crude oils at 350 and 450 °C.

For Menggulin crude oil, Coke a—formed through oxidation-dominated coking at 350 °C—is characterized by an enrichment of oxygen-containing functional groups and residual aliphatic carbons. Its TGA curve displays a pronounced weight loss plateau between 200–400 °C, indicative of the preferential oxidation of highly reactive carbon fractions. The DSC profile reveals an intense exothermic peak in the range of 300–400 °C, underscoring its elevated combustion reactivity; this is consistent with its moderate aromatization degree as suggested by the peak area. Conversely, Coke b—resulting from deep pyrolysis at 450 °C—boasts a core structure predominantly of highly condensed aromatic carbons. Its TGA weight loss is primarily observed in the high-temperature bracket of 450–600 °C, with minimal weight loss at lower temperatures. Correspondingly, the DSC exothermic peak is shifted to approximately 500 °C, denoting the diminished combustion reactivity of these condensed aromatic carbons. However, its advanced aromatization degree results in a more substantial exothermic peak area.

For Xinjiang crude oil, Coke c—formed at 350 °C with a long-chain alkane-dominated composition—retains a significant amount of aliphatic carbons but lacks oxygen-containing functional groups. Its TGA curve exhibits two distinct stages: a minor weight loss between 200–300 °C and a primary weight loss from 300–500 °C, reflecting the progressive combustion of aliphatic carbons. The DSC profile reveals a broadened exothermic peak spanning 350–450 °C, suggesting the concurrent combustion of both aliphatic and weakly condensed aromatic carbons. In contrast, coke d—formed through balanced pyrolysis–oxidation at 450 °C—contains moderate levels of residual aliphatic carbons and oxygen-containing functional groups. Its TGA weight loss occurs across two temperature ranges: medium-low (300–400 °C) and high (400–600 °C). Correspondingly, the DSC profile demonstrates bimodal characteristics, featuring a smaller medium-low temperature peak and a more pronounced high-temperature main peak. Notably, the main peak temperature of Sample d is lower than that of Sample b, which can be attributed to the enhanced combustion reactivity conferred by oxygen-containing functional groups. Additionally, its exothermic peak area exceeds that of Sample c, likely due to increased aromatization.

The aforementioned differences in combustion behavior are essentially the result of synergistic regulation by crude oil composition and coking temperature. The higher temperature sensitivity of Menggulin crude-oil-derived coke is due to its intrinsic high oxidative activity being significantly inhibited with increasing temperature. In contrast, the two-stage combustion characteristics of Xinjiang crude-oil-derived coke were determined by its long-chain alkane dominated carbon structure, where oxidation was less inhibited by temperature. Moreover, increasing the coking temperature shifted the combustion interval of cokes from the same crude oil to higher temperatures, with decreasing aliphatic/oxygenated carbon content and increasing aromatic carbon abundance, and total heat release increased as the degree of aromatization improved. As a result, this study provides experimental evidence based on thermal behavior for precisely regulating coke combustion efficiency and optimizing reservoir oil recovery during fire flooding.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the coke formation, structure, and combustion behavior of paraffin-based Menggulin and naphthenic-based Xinjiang heavy oils under simulated fire flooding (350 °C/450 °C) using GC-MS, SEM, 13C ss-NMR, and TG-DSC. The composition of the crude oil is a dominant factor in coking: Xinjiang oil, rich in cyclic hydrocarbons and heteroatoms, forms more compact coke at 350 °C, whereas Menggulin oil, composed primarily of long-chain alkanes, yields loose coke at 350 °C but transitions to dense, highly aromatized coke at 450 °C, corresponding to the alkane cracking–polymerization threshold. Temperature differentially regulates oxidative processes, thereby shaping the functional groups of the coke and its subsequent combustion; oxygenated and aliphatic-rich cokes exhibit high reactivity, while aromatized cokes release greater amounts of heat. These findings provide practical guidance for optimizing energy supply during fire flooding, suggesting higher temperatures for paraffin-based oils and moderate temperatures for naphthenic oils to stabilize the process. This work contributes to the theory of ISC and supports the precise regulation of combustion efficiency and heavy oil recovery. Optimizing temperature control during ISC significantly enhances crude oil production and recovery efficiency, while improving reservoir fluid mobility and refining oil quality. Precise temperature regulation effectively reduces the viscosity of heavy components and increases the yield of light distillates. Additionally, this approach minimizes the emission of harmful gases and the generation of residues associated with incomplete combustion, thereby improving extraction and distillation efficiency while mitigating potential environmental impacts.