Integrated Understandings and Principal Practices of Water Flooding Development in a Thick Porous Carbonate Reservoir: Case Study of the B Oilfield in the Middle East

Abstract

1. Introduction

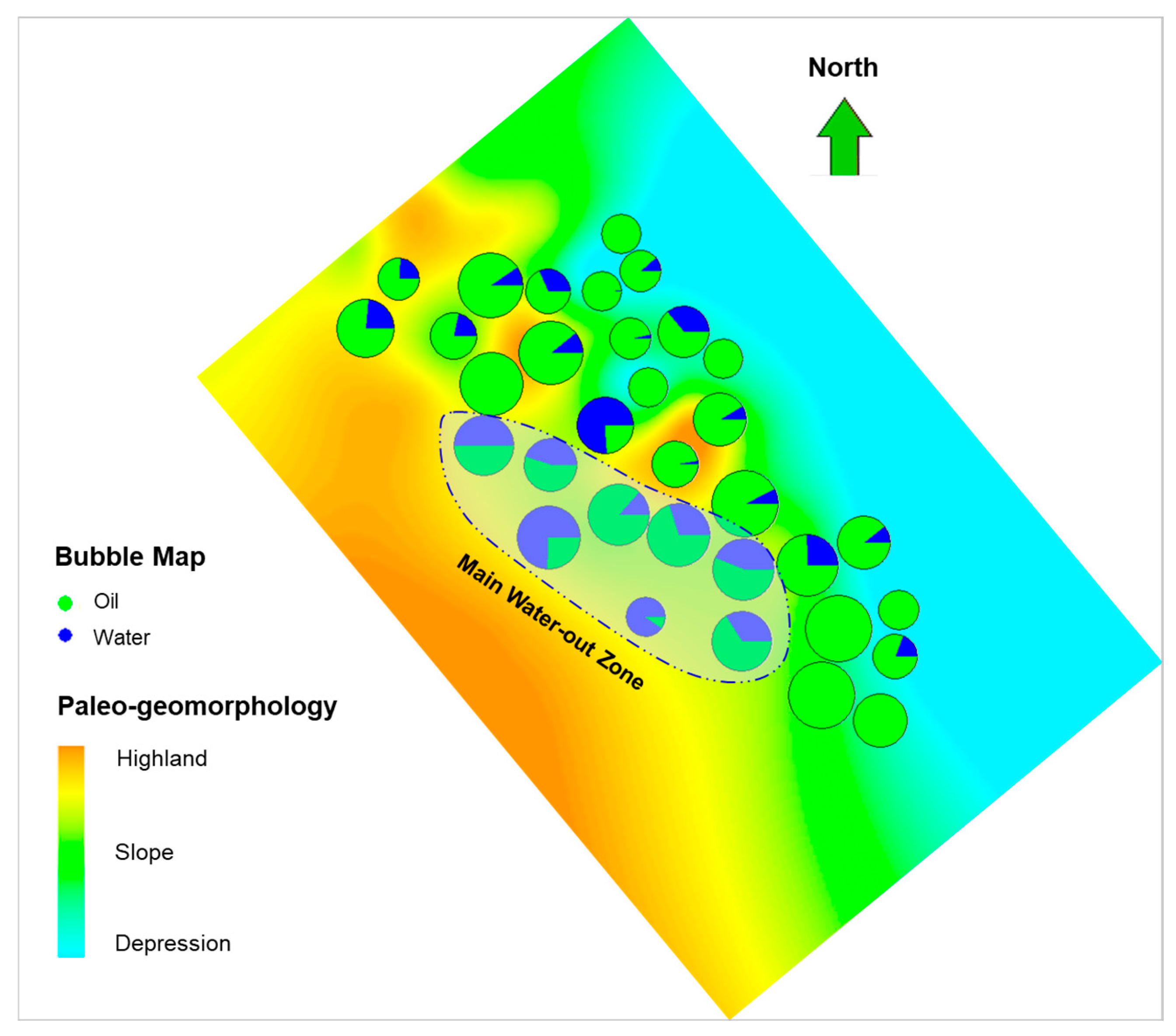

2. Field Geology

2.1. Depositional Facies

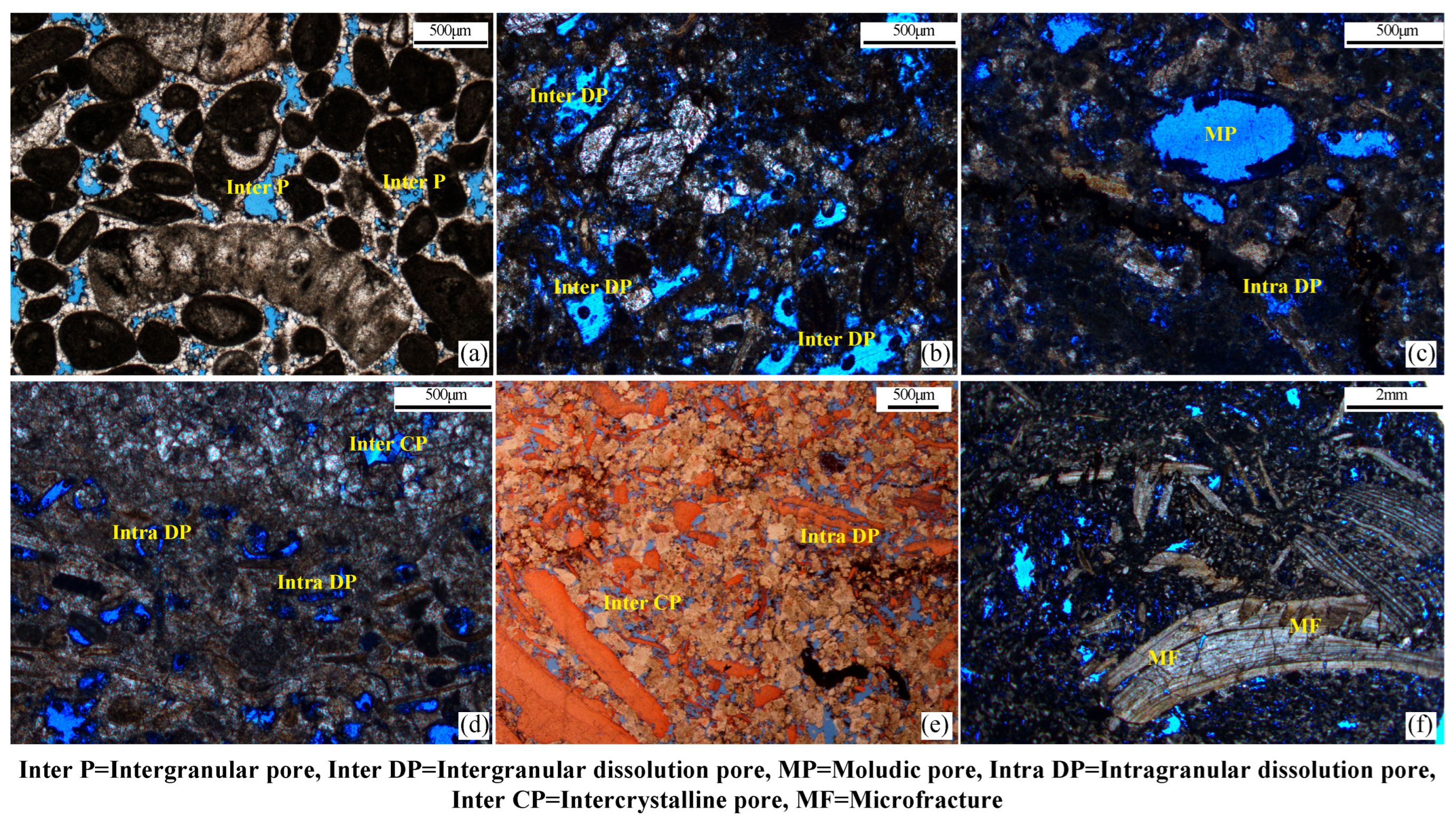

2.2. Reservoir Characteristics

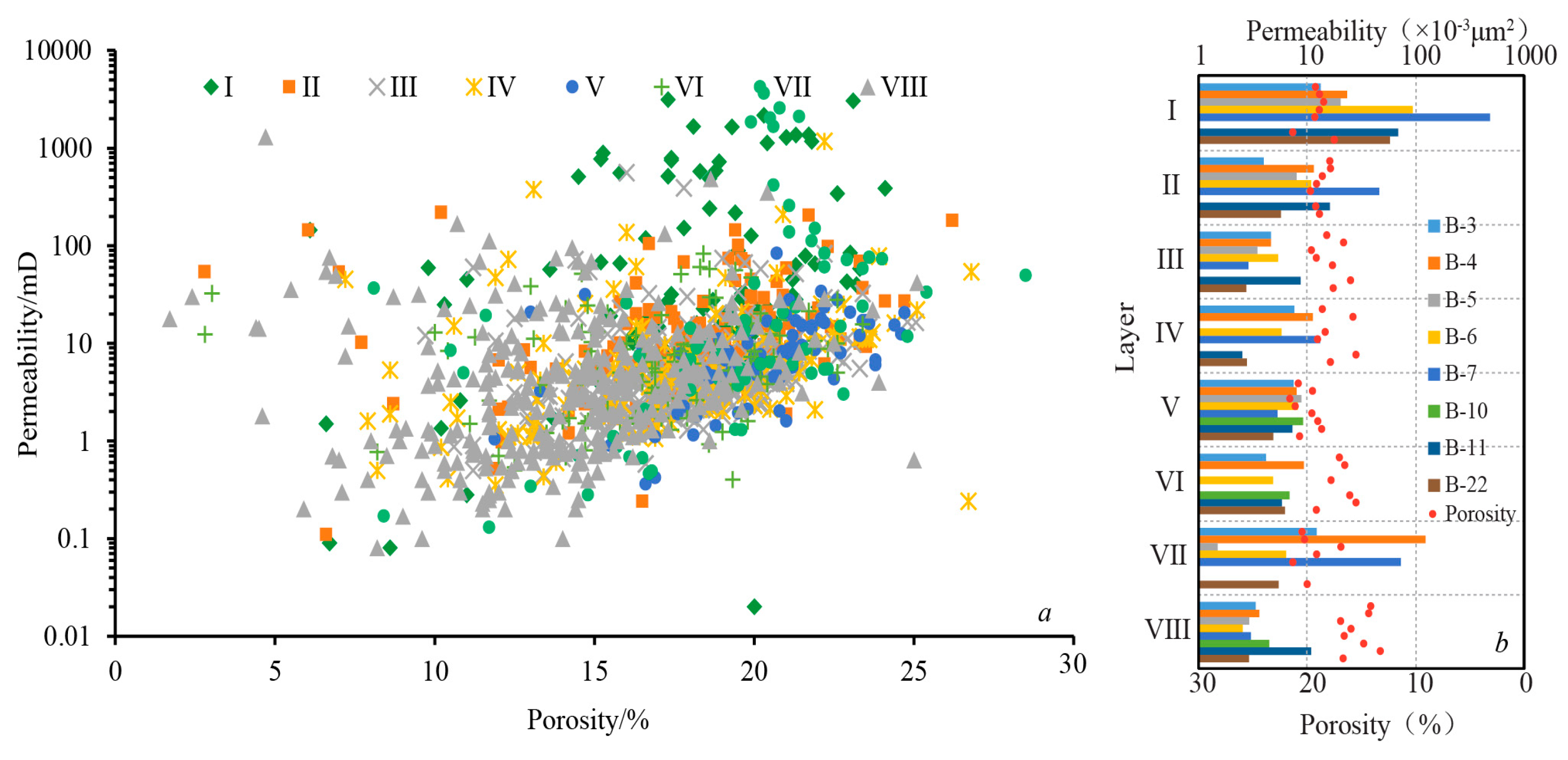

2.3. Petrophysical Properties

2.4. Reservoir Connectivity

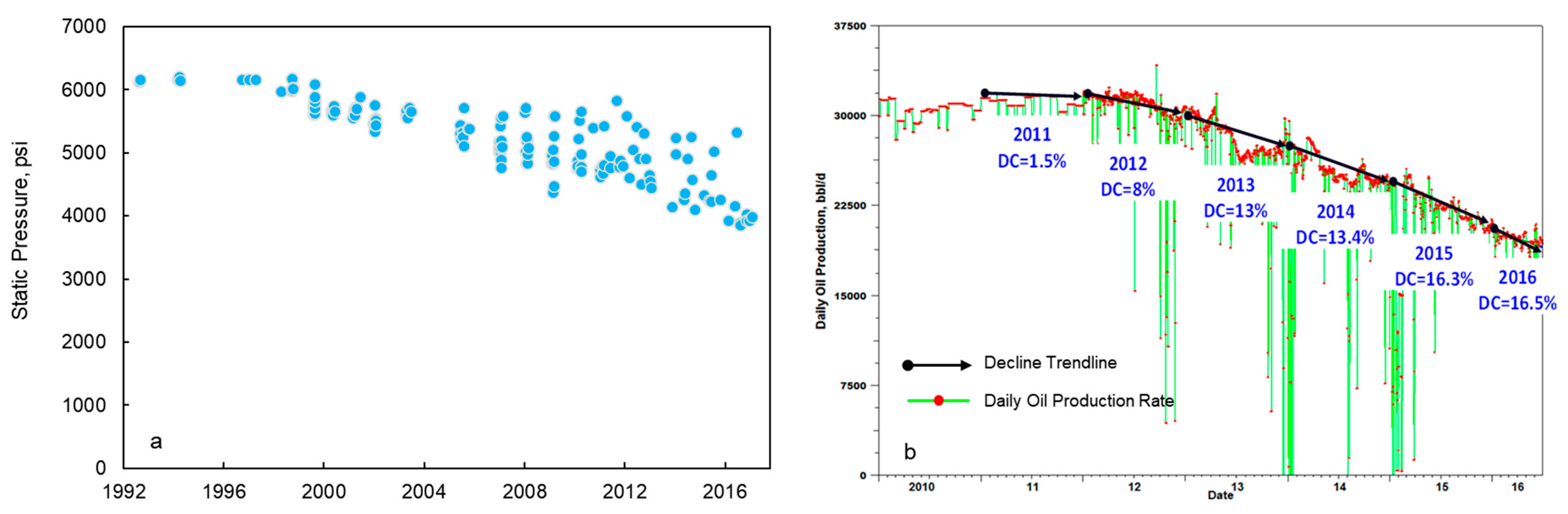

3. Oilfield Development History

4. Water Flooding Research

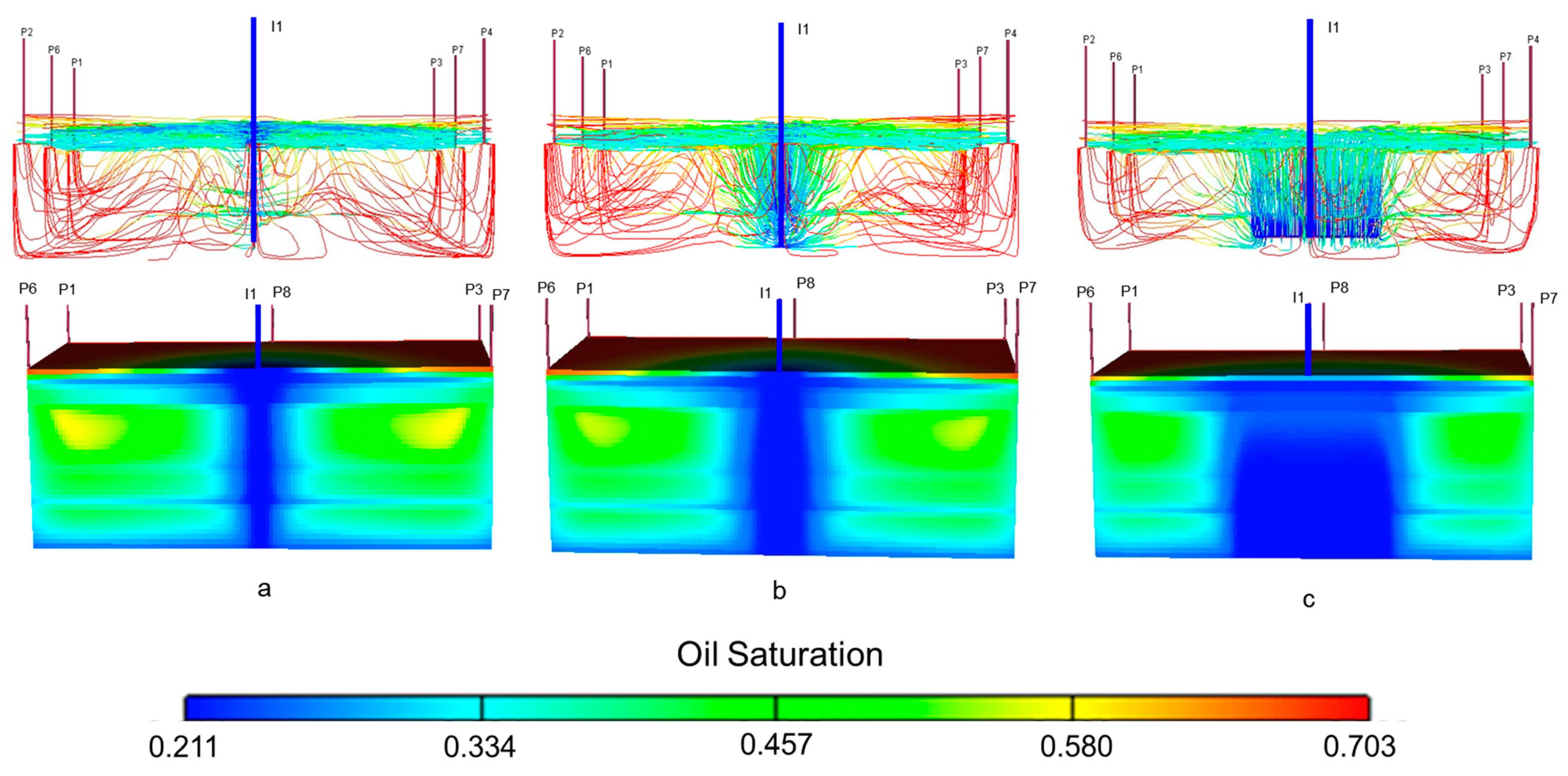

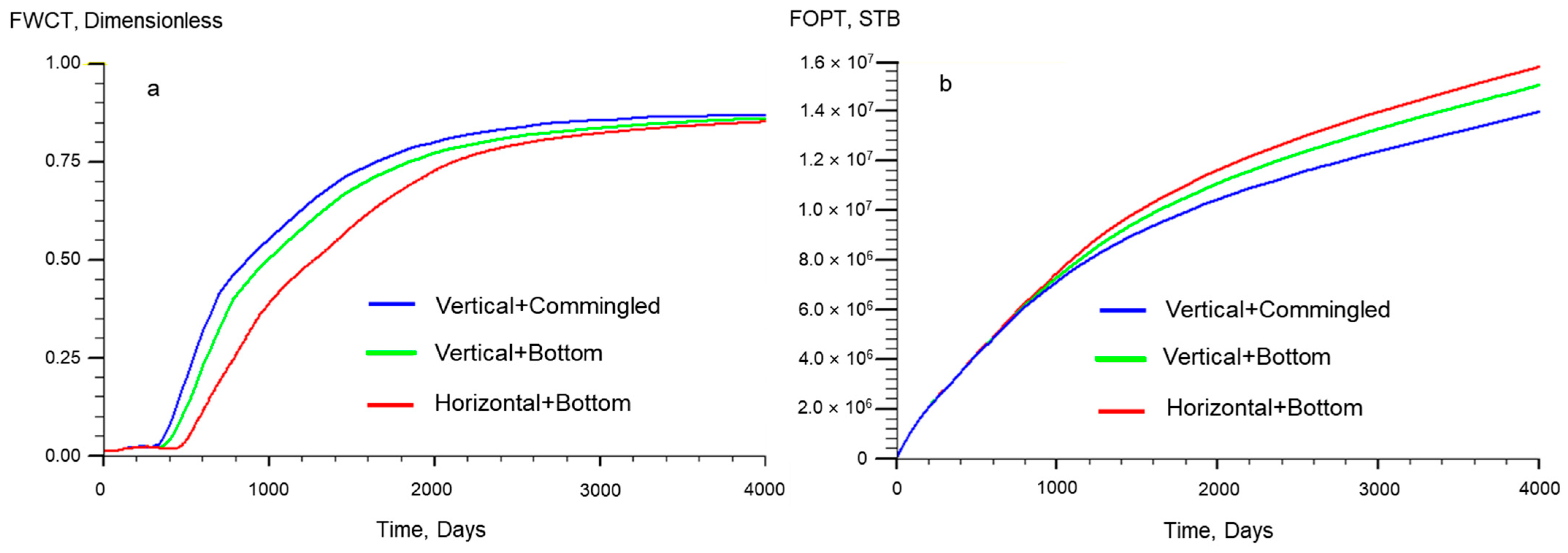

4.1. Water Injection Mode Investigation

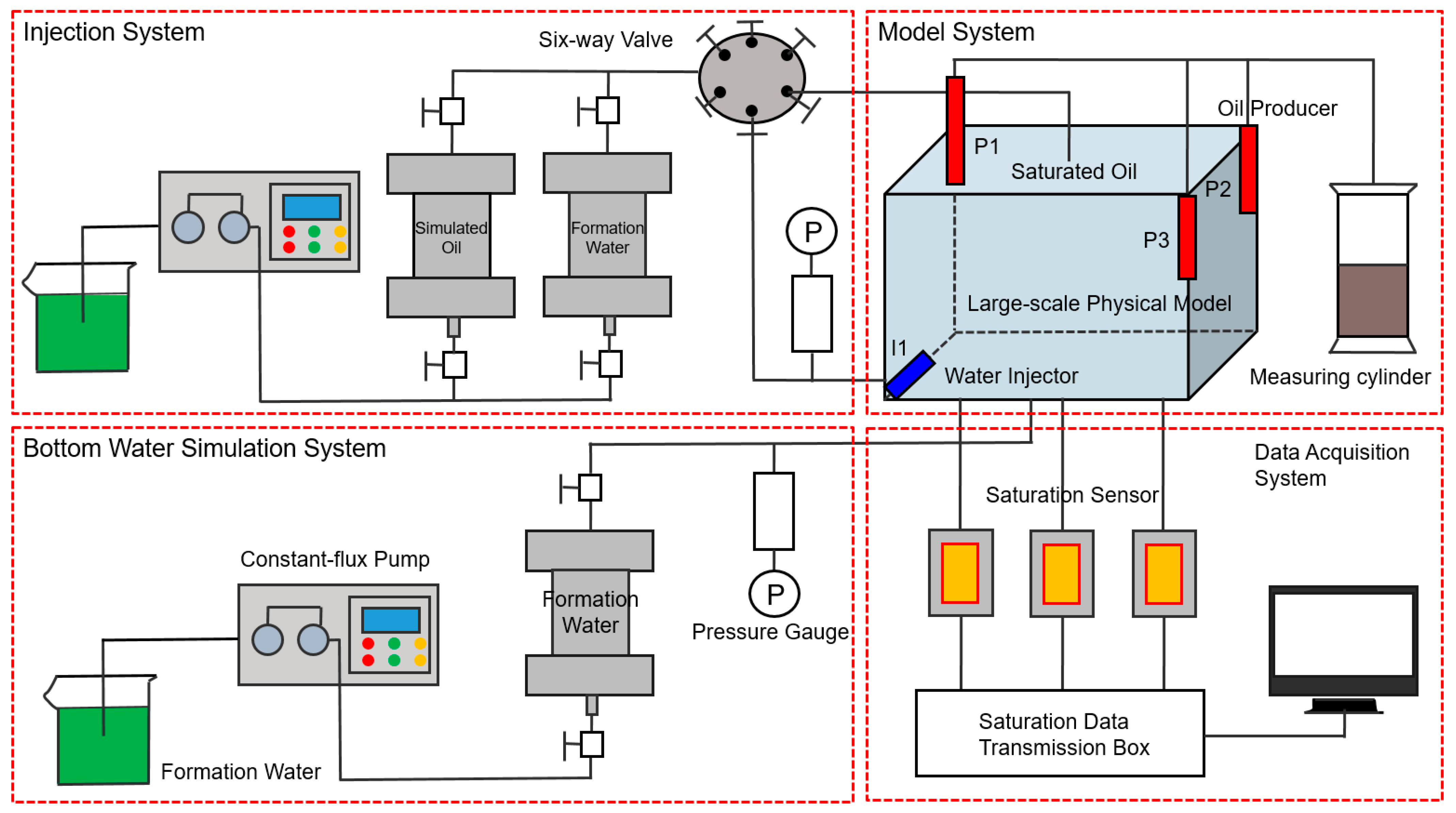

4.2. Large-Scale Physical Model Experiment

4.2.1. Anisotropic Characteristics of the Model

4.2.2. Physical Simulation Model Design

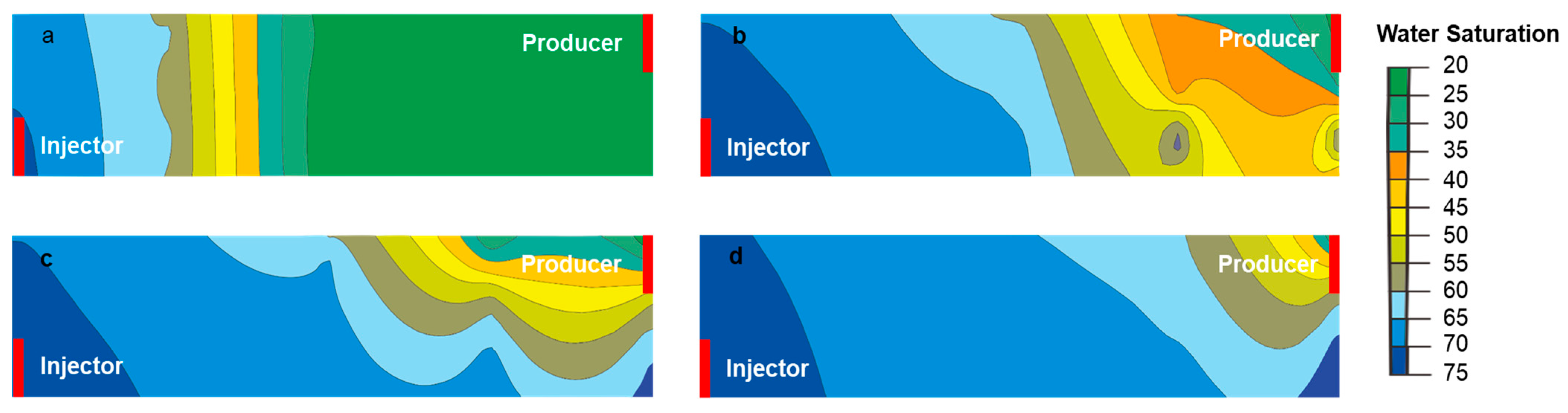

4.2.3. Analysis of the Main Mechanism

5. Principal Practices of Water Flooding

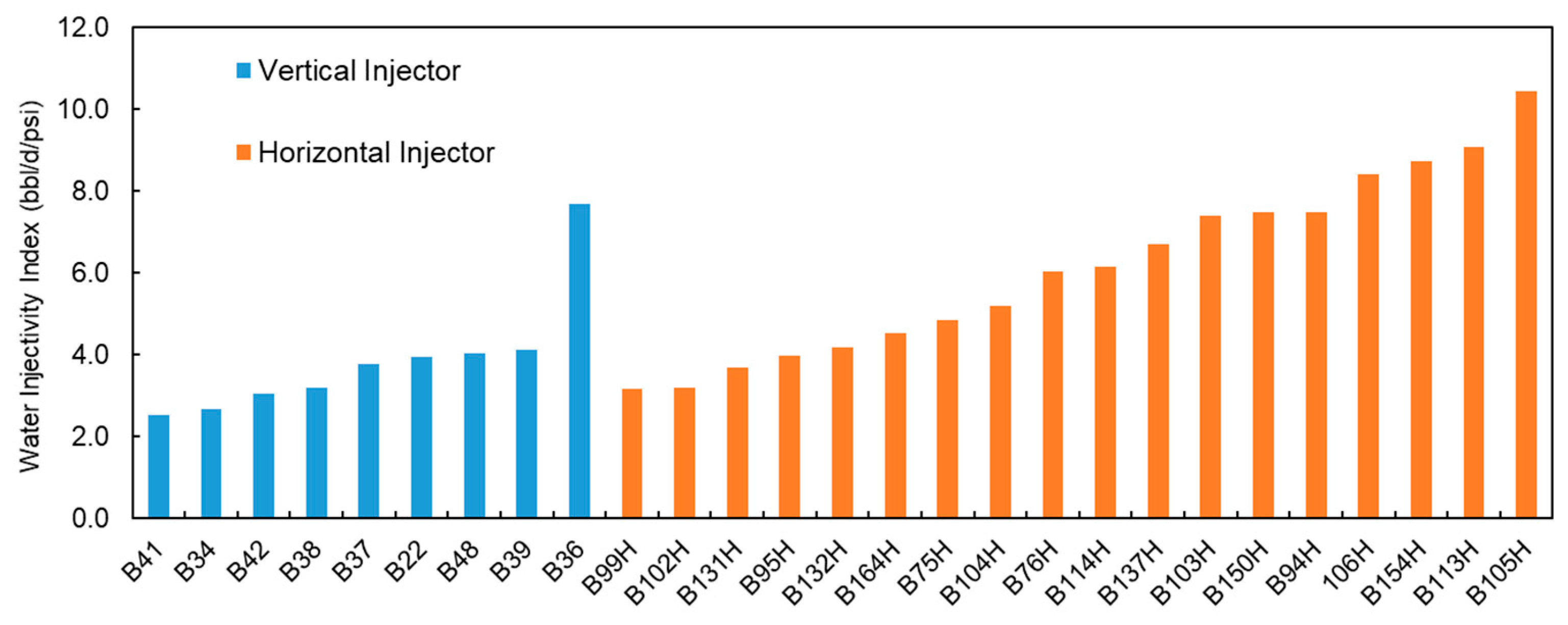

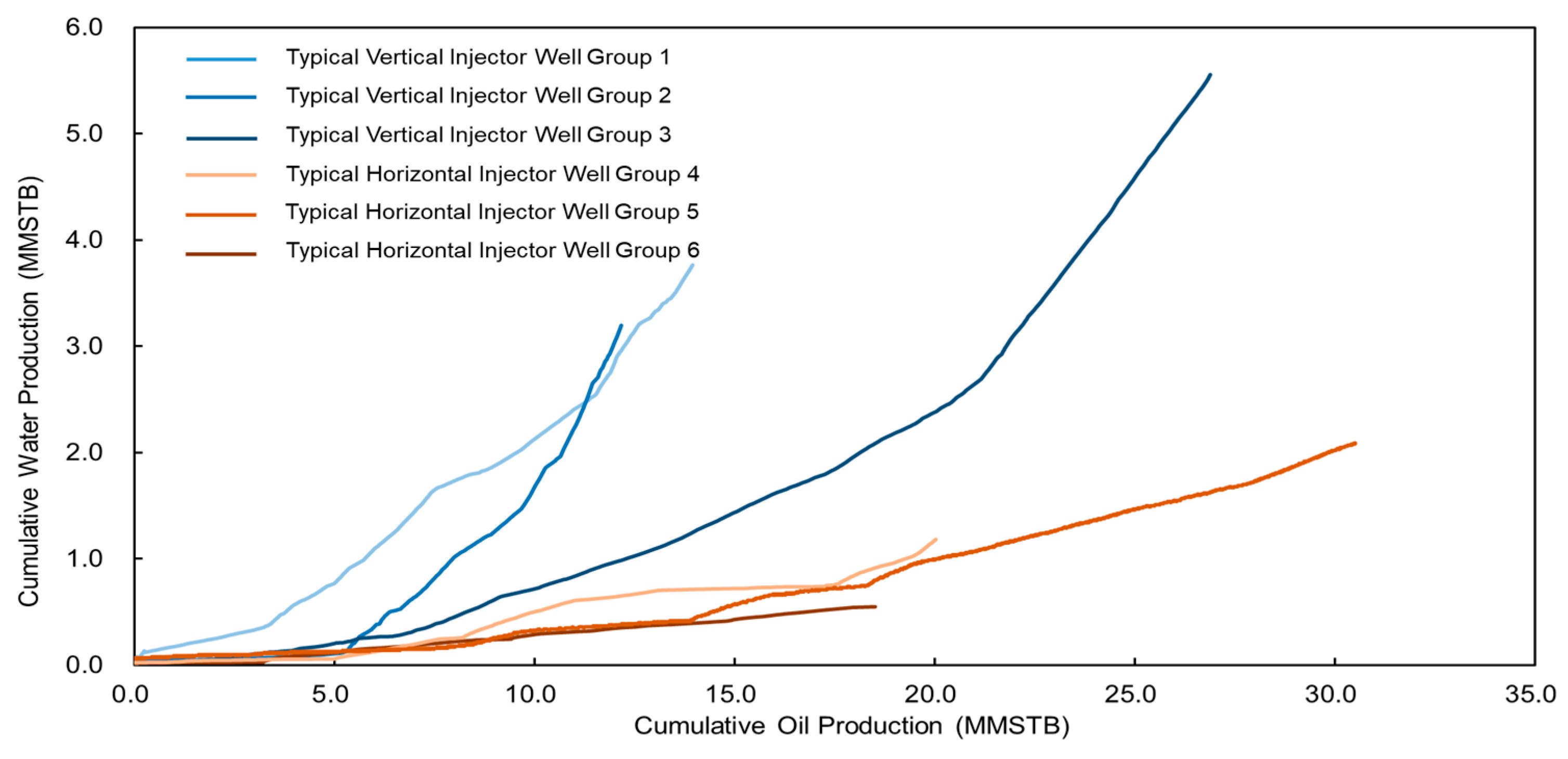

5.1. Well Type Optimization

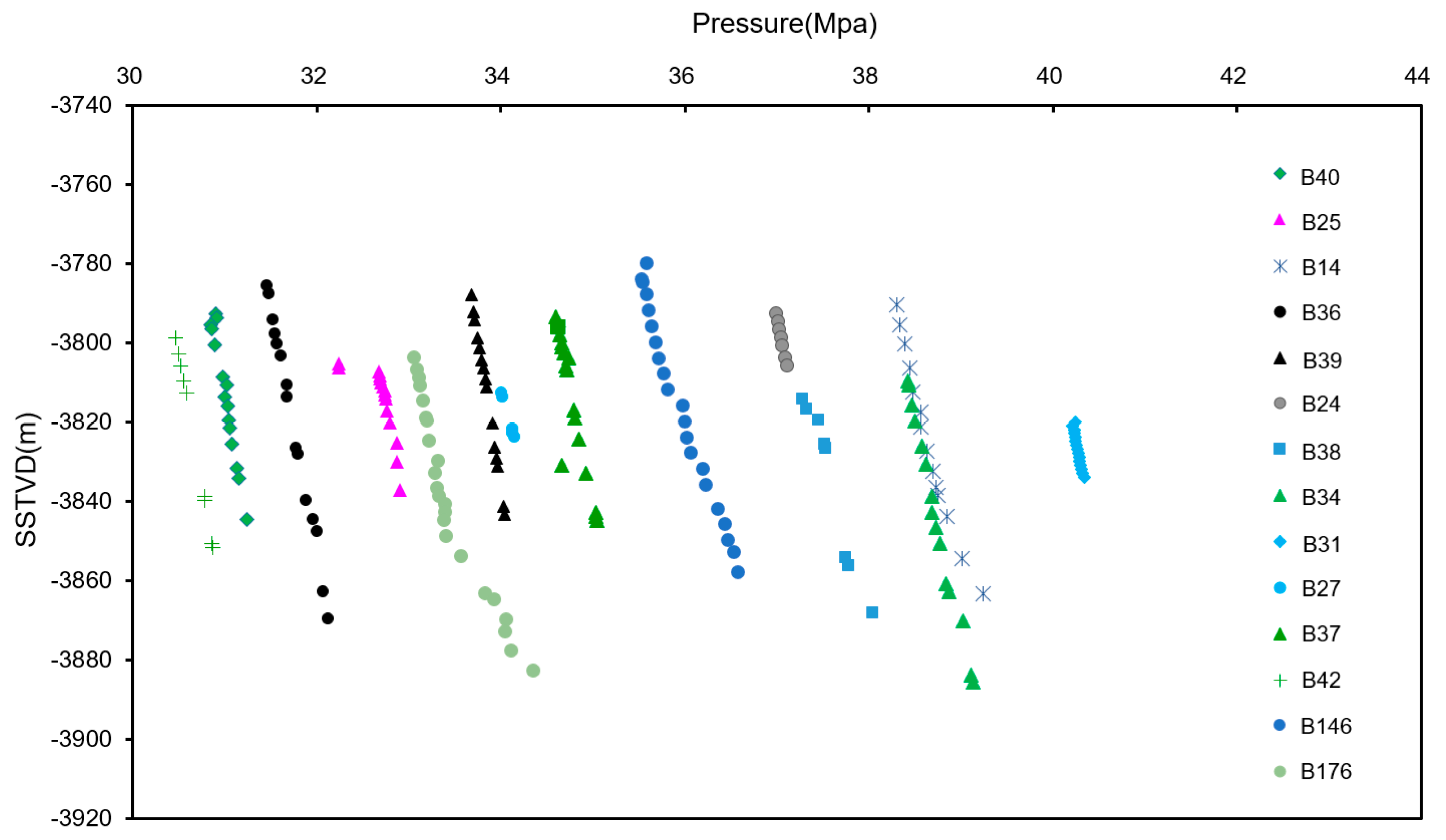

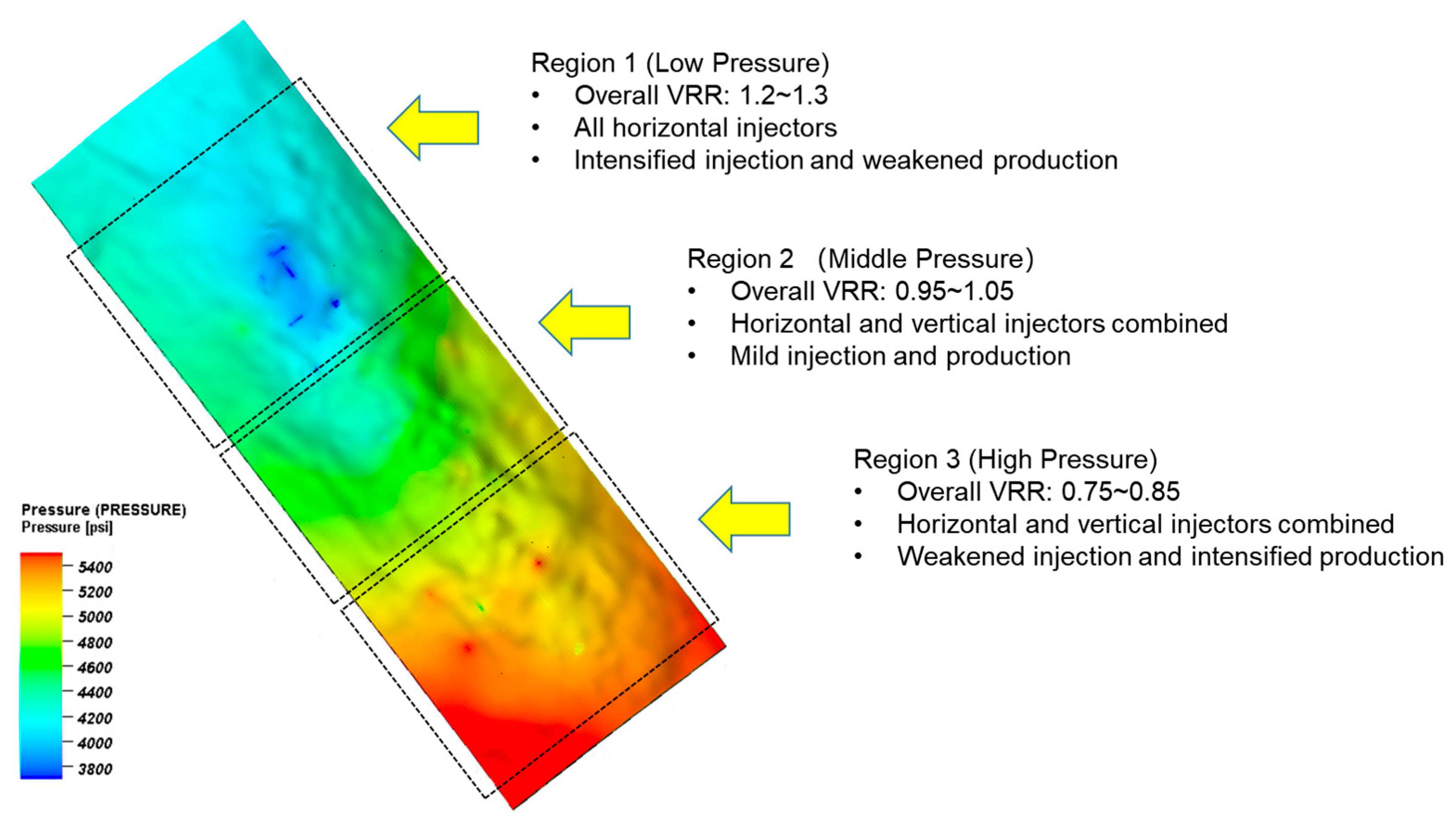

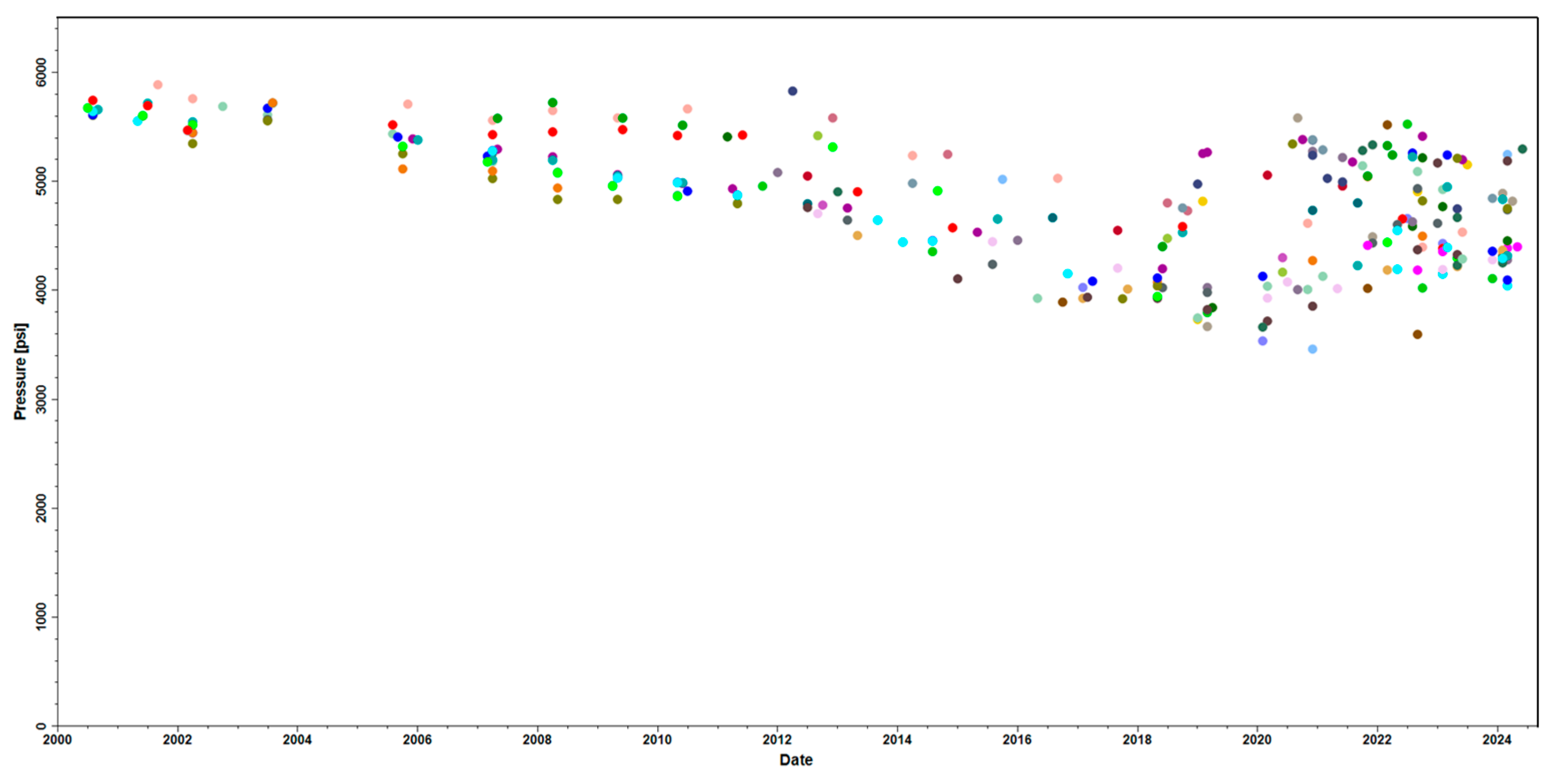

5.2. Pressure-Based Differentiated Water Injection

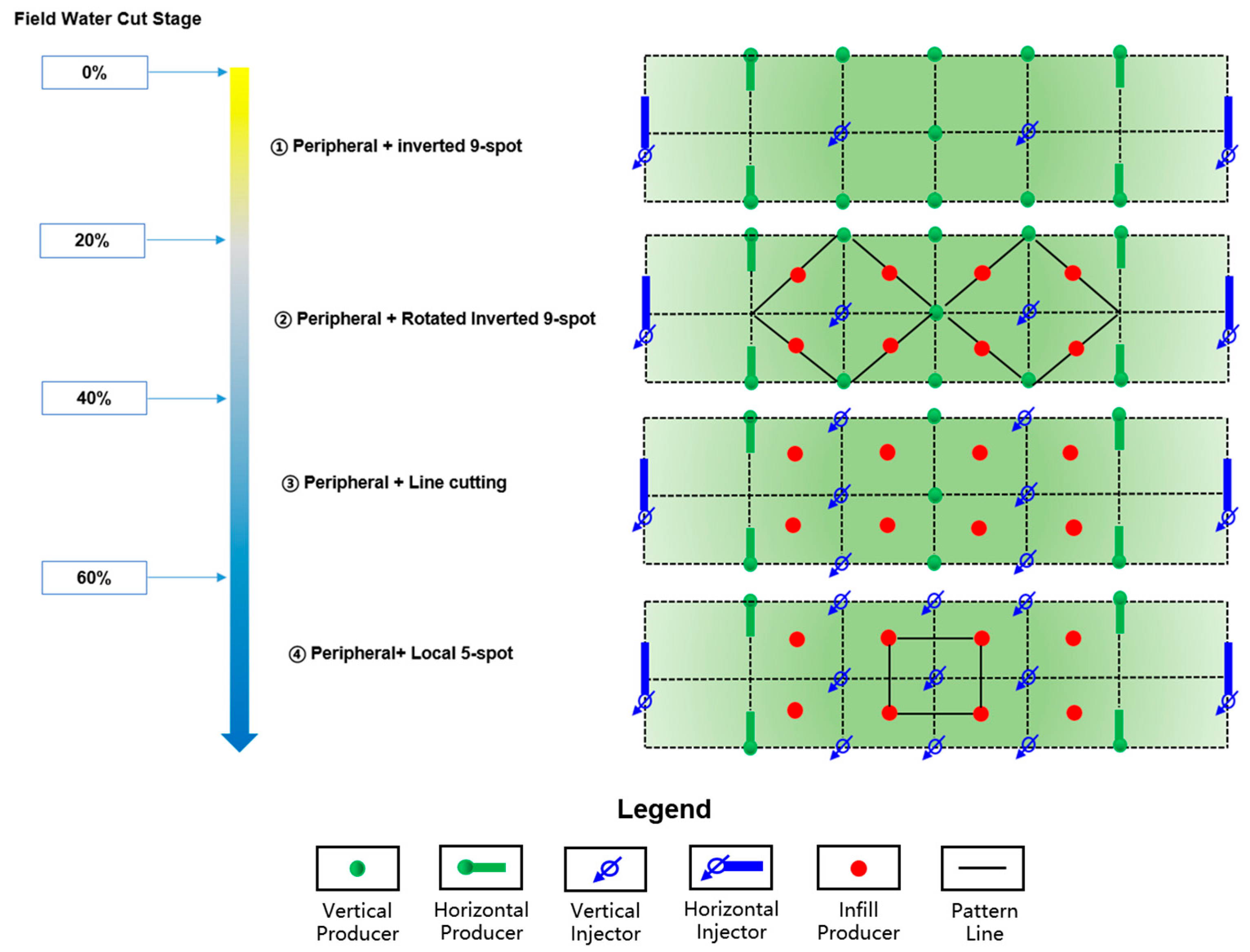

5.3. Well Pattern Conversion

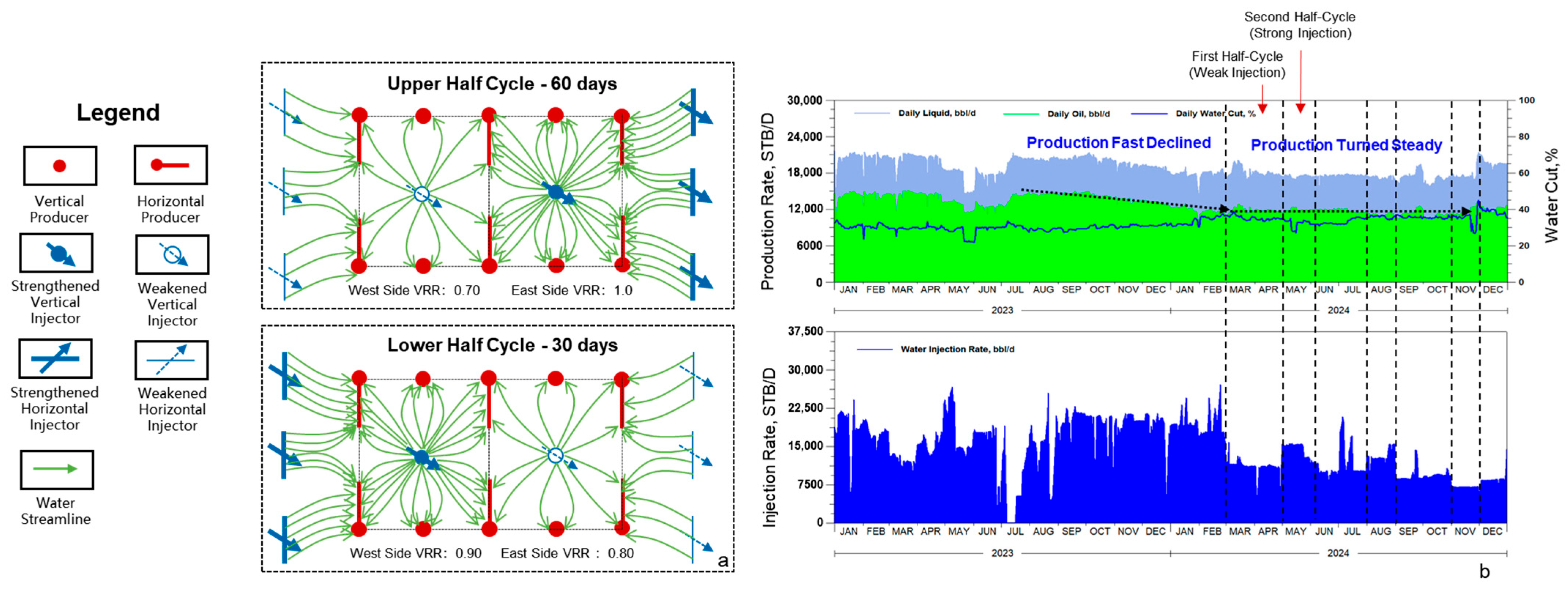

5.4. Unstable Water Injection Technology

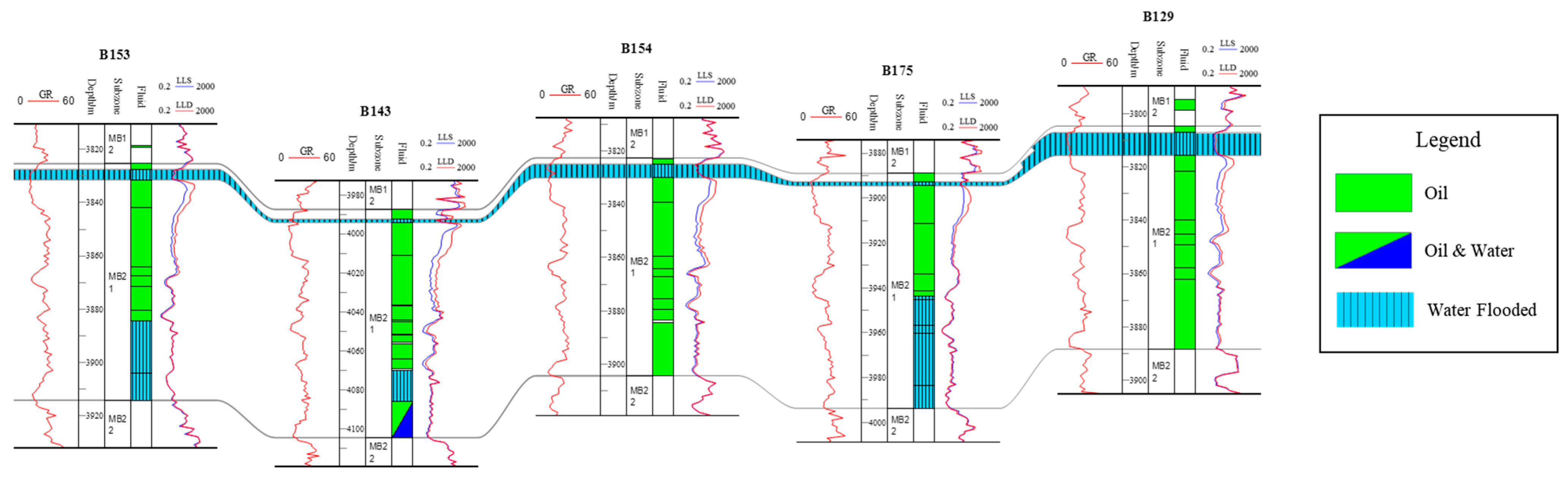

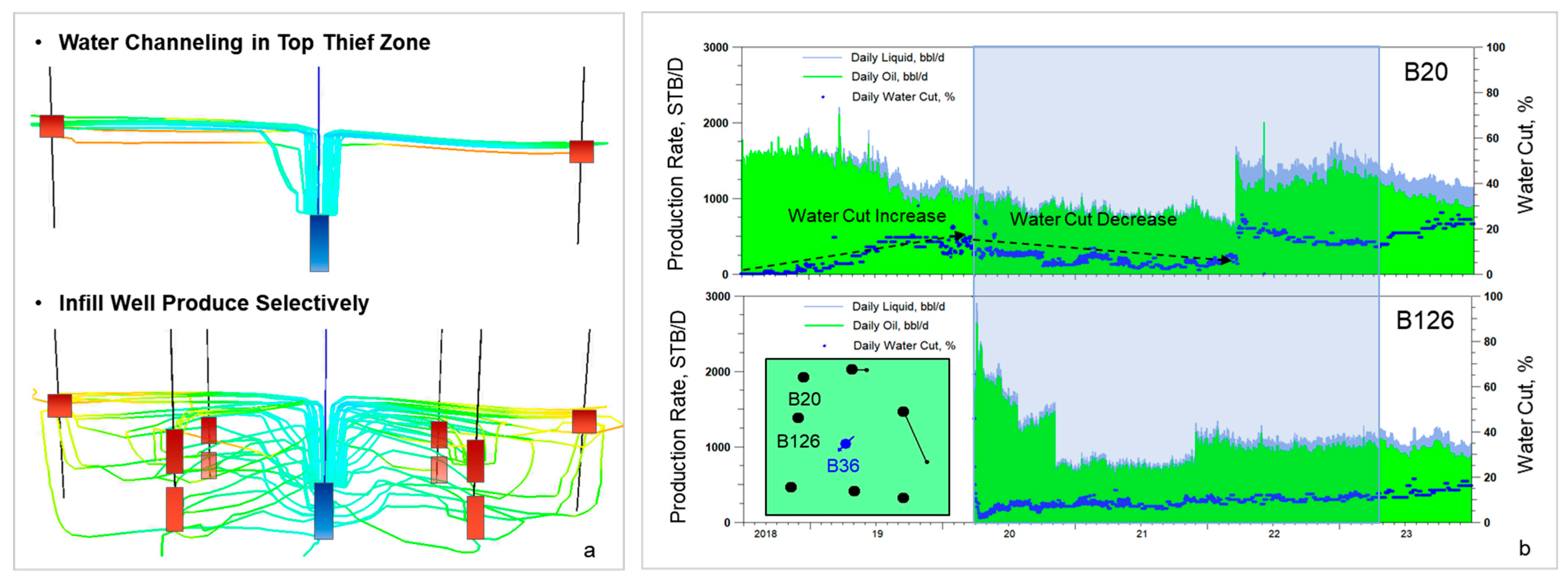

5.5. Selective Perforation

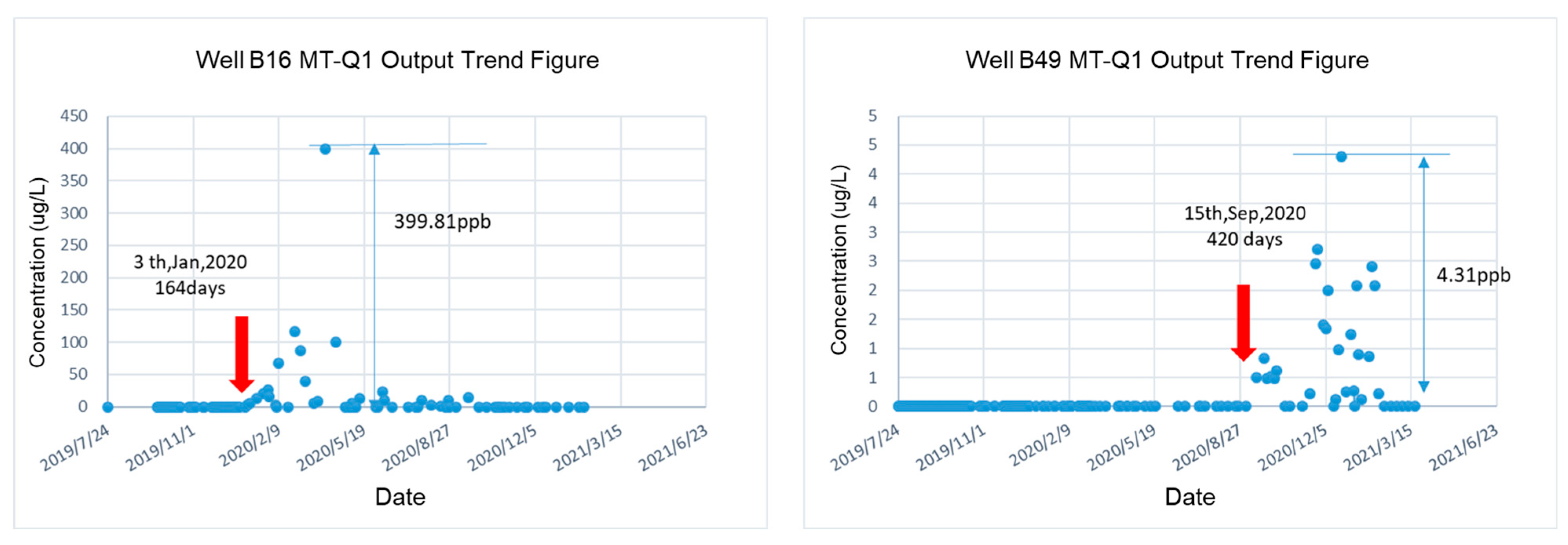

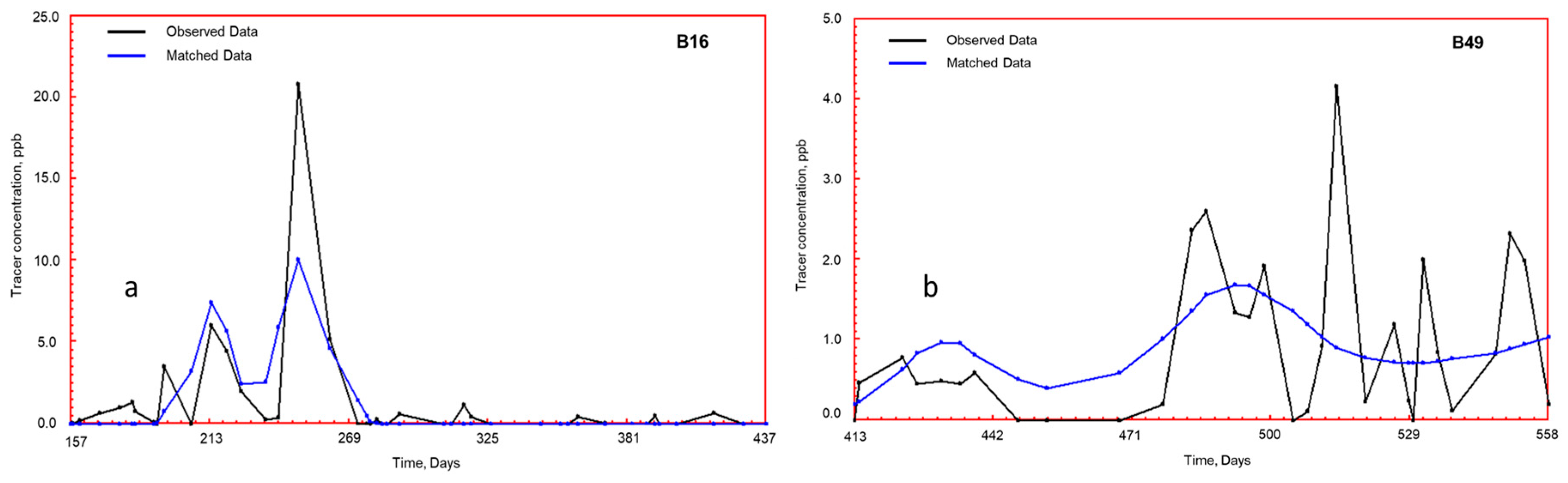

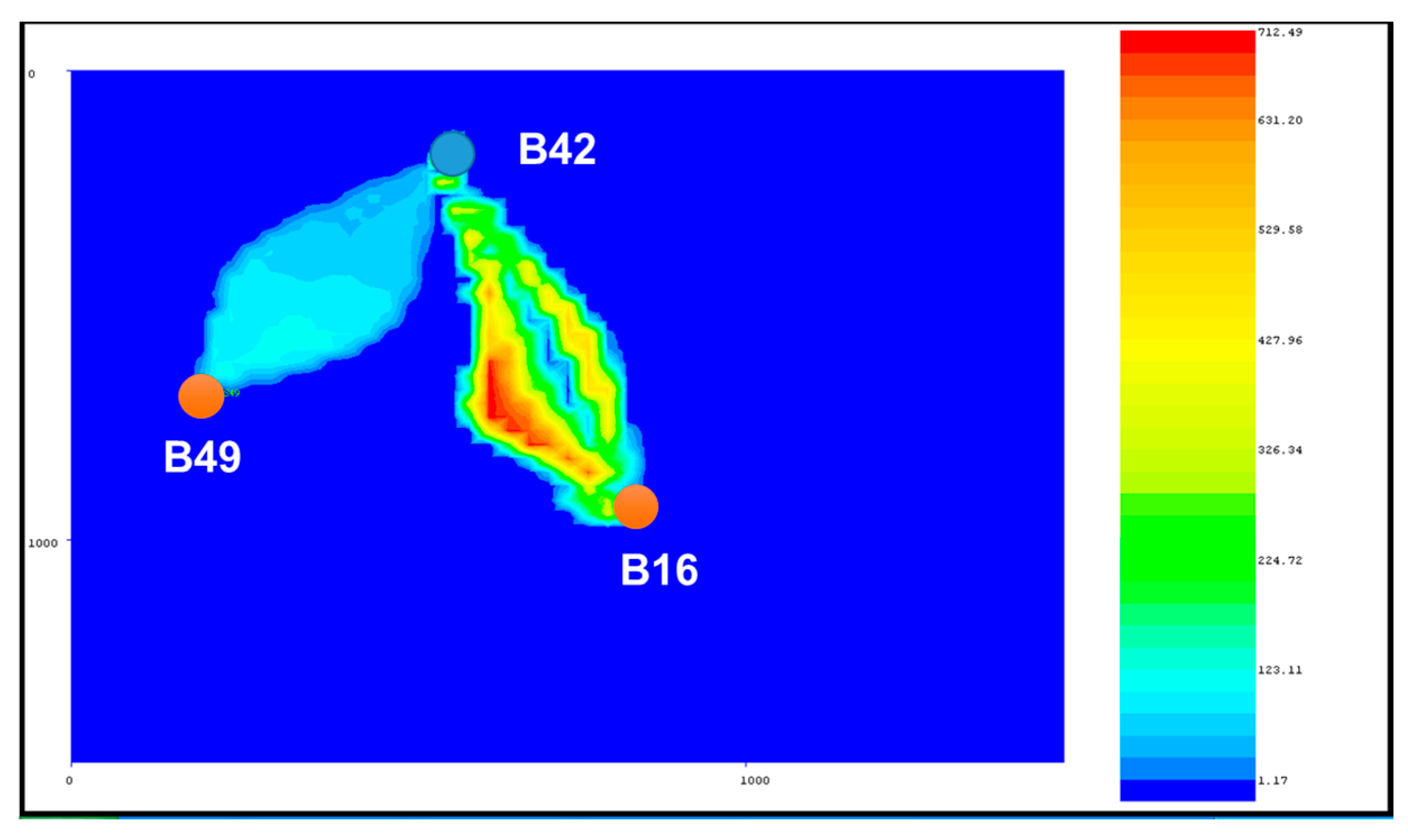

5.6. Tracer Surveillance

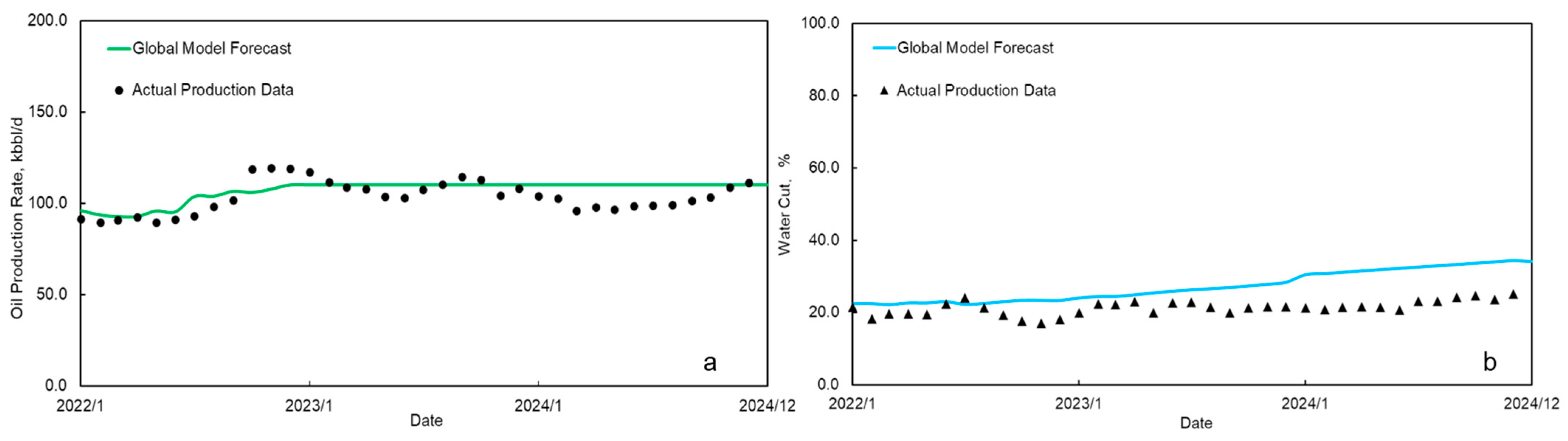

6. Field Application Effect

7. Discussion

- (1)

- As the contract mode of the B Oilfield belongs to the TSC (Technical Service Contract) framework, the CAPEX and OPEX paid by operators in advance will be fully recovered by the governments of countries with resources [47]. The final benefits for a contractor are equal to the product of the remuneration fee per barrel and increased oil production beyond the base production set in the contract, and the profits of contractors are mainly affected by the reached PPT (production plateau target) and the length of the stable production period. Hence, this paper mainly concentrates on the technical success results from a series of development technologies instead of economic enhancement. However, in other contract modes, economic evaluation is also necessary to comprehensively demonstrate the enhancements led by water flooding technologies.

- (2)

- In this paper, the scale of research mainly focuses on the macro level, especially for the water flooding techniques applied in the B Oilfield. However, for the carbonate reservoir in the Middle East, the diversity of porous structures has a great impact on the fluid flow characteristics. For instance, different water drive velocities and displacement multiples may lead to a completely different recovery effect in different rock types due to microscopic heterogeneity of the pore media [17]. Therefore, microscopic water flooding experiments of different rock types need to be conducted to obtain an in-depth understanding of fluid behavior in this type of reservoir.

- (3)

- For the thick anti-rhythmic reservoir like MB21 of the B Oilfield, the water flooding technique of IBPT is able to acquire a positive development effect by making use of the gravitational differentiation and prolonging the water breakthrough time. Yet, in the area of the Middle East, there are thinner reservoirs with a thickness of less than 20 m as well [21]. Under this reservoir condition, the wells’ productivity and injectivity need to be satisfied first, which makes it preferable for horizontal wells and difficult to apply the strategy of IBPT and selective perforation in the meantime.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mu, L.X.; Fan, Z.F.; Xu, A.Z. Development characteristics, models and strategies for overseas oil and gas fields. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, D.G.; Song, B.; Liu, P. A fast method of waterflooding performance forecast for large-scale thick carbonate reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 192, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Li, Y.; Li, F.F.; Yi, L.; Song, B.; Zhu, G.; Su, H.; Wei, L.; Yang, C. Separate-layer balanced waterflooding development technology for thick and complex carbonate reservoirs in the Middle East. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadeesian, A.M.; Al-Jawed, S.N.; Saleh, A.H.; Sherwani, G.H. Mishrif carbonates facies and diagenesis glossary, South Iraq microfacies investigation technique: Types, classification, and related diagenetic impacts. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 10373–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.J.; Hakimi, M.H.; Najaf, A.A. Organic geochemistry characterization of crude oils from Mishrif reservoir rocks in the southern Mesopotamian Basin, South Iraq: Implication for source input and paleoenvironmental conditions. Egypt. J. Petrol. 2018, 27, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, M.; Mahdi, M.M.; Alali, R. Microfacies and depositional environment of Mishrif Formation, North Rumaila oil field, southern Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2019, 52, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.M.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, R.; Jin, Z.; Chen, Y. Control factors of reservoir oil-bearing difference of Cretaceous Mishrif Formation in the H oilfield, Iraq. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.J.; Ettensohn, F.R.; Handhal, A.M.; Al-Abadi, A. Facies analysis of the Middle Cretaceous Mishrif Formation in southern Iraq borehole image logs and core thin-sections as a tool. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2021, 133, 105324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, K.B.; Ma, Y.S.; Liu, B.; Song, X.; Ge, Y.; Liu, H.; Hoffmann, R.; Immenhauser, A. Control of depositional and diagenetic processes on the reservoir properties of the Mishrif Formation in the AD oilfield, Central Mesopotamian Basin, Iraq. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 132, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.X.; Jiang, Z.X.; Sun, C.; Ma, B.; Su, Z.; Wan, X.; Han, J.; Wu, G. An overview of the differential carbonate reservoir characteristic and exploitation challenge in Tarim Basin (NW China). Energies 2023, 16, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, A.A.; Ismail, J.M.; Mahdi, M.M. High resolution sequence stratigraphy of the Mishrif Formation (Cenomanian-Early Turonian) at zubair oilfield (Al-Rafdhiah dome), southern Iraq. Pet. Res. 2024, 9, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Hou, J.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luo, M.; Zheng, Z. Residual oil distribution characteristic of fractured-cavity carbonate reservoir after water flooding and enhanced oil recovery by N2 flooding of fractured-cavity carbonate reservoir. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2015, 129, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J.; Lyu, D.L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, J. Production optimization for water flooding in fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoir—From laboratory physical model to reservoir operation. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 184, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.J.; He, J.; Chen, P.Y.; Li, C.; Dai, W.; Sun, F.; Tong, Y.; Rao, S.; Wang, J. Key Technologies for the Efficient Development of Thick and Complex Carbonate Reservoirs in the Middle East. Energies 2024, 17, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Q.; Liu, Y.T.; Xue, L.; Yang, L.; Yuan, Z.; Jian, C. An investigation on water flooding performance and pattern of porous carbonate reservoirs with bottom water. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 200, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.W.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, C.Y. Longitudinal water flooding seepage law of typical Mishrif reservoir in the Middle East. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Pi, J.; Tong, K.J. Pore-scale experimental investigation of the residual oil formation in carbonate sample from the Middle East. Processes 2023, 11, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.M.; Wang, S.; Sun, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Hu, D.; Chen, Y. Using cyclic alternating water injection to enhance oil recovery for carbonate reservoirs developed by linear horizontal well pattern. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M. From field trial to full-scale deployment of pulse waterflooding on mature oil fields. Incremental oil at no cost. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2–5 October 2023. Paper number SPE-216329-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.M.; Li, Y. Optimum development options and strategies for water injection development of carbonate reservoirs in the Middle East. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Li, B.Z. Classified Evaluation methods and waterflood development strategies for carbonate reservoir in the Middle East. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, A.A.; Al-Saleh, S.; Al-Kaabi, A.; Al-Jawfi, M.S. Laboratory investigation of the impact of injection water salinity and ionic content on oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2011, 14, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantariasl, A.; Tale, F.; Parsaei, R.; Keshavarz, A.; Jahanbakhsh, A.; Maroto-Valer, M.M.; Mosallanezhad, A. Optimum salinity/composition for low salinity water injection in carbonate rocks: A geochemical modelling approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Façanha, J.M.F.; Farzaneh, S.A.; Sohrabi, M. Qualitative assessment of improved oil recovery and wettability alteration by low salinity water injection for heterogeneous carbonates. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2022, 213, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandoozi, S.; Malayeri, M.R.; Riazi, M.; Ghaedi, M. Inspectional and dimensional analyses for scaling of low salinity waterflooding (LSWF): From core to field scale. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 189, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahdari, Z.; Khandoozi, S.; Ghaedi, M.; Malayeri, M.R. Optimization of injection water composition during low salinity water flooding in carbonate rocks: A numerical simulation study. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2022, 209, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Y.; Mansouri, M.; Pourafshary, P. Enhanced oil recovery by using modified ZnO nanocomposites in sandstone oil reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.Y.; Allam, N.K. Unveiling the synergistic effect of ZnO nanoparticles and surfactant colloids for enhanced oil recovery. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2019, 29, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborda, E.A.; Alvarado, V.; Franco, C.A.; Cortés, F.B. Rheological demonstration of alteration in the heavy crude oil fluid structure upon addition of nanoparticles. Fuel 2017, 189, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarbeigi, E.; Mohammadidoust, A.; Ranjbar, B. A review on applications of nanoparticles in the enhanced oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 1811–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihekoronye, K.K. Formulation of bio-surfactant augmented with nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery. In Proceedings of the SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, 1–3 August 2022. Paper number SPE-212001-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, F.; Belhaj, H.; Morales, R.; Velasquez, R.; AlDhuhoori, M.; Alhameli, F. Electrical/electromagnetic enhanced oil recovery for unconventional reservoirs: A review of research and field applications in Latin America. In Proceedings of the SPE Oman Petroleum & Energy Show and Conference, Muscat, Oman, 22–24 April 2024. Paper number SPE-218665-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Musawi, F.A.; Idan, R.M.; Salih, A.L.M. Reservoir characterization, Facies distribution, and sequence stratigraphy of Mishrif Formation in a selected oilfield, South of Iraq. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Pure Science (ISCPS-2020), Najaf, Iraq, 13–14 July 2020. Paper number ISCPS-012073. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.H.M.; Ali, Z.; Embong, M.K.; Azmi, A.A. Microfacies analysis and reservoir characterisation of late cenomanian to early turonian Mishrif reservoirs, garraf field, Iraq. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Beijing China, 26–28 March 2013. Paper number IPTC-16976. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ameri, T.K.; Al-Khafaji, A.J.; Zumberge, J. Petroleum system analysis of the Mishrif reservoir in the ratawi, Zubair, North and South Rumaila oil fields, southern Iraq. GeoArabia 2009, 14, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqrawi, A.A.M.; Thehni, G.A.; Sherwani, G.H.; Kareem, B.M.A. Mid-Cretaceous rudist-bearing carbonates of the Mishrif Formation: An important reservoir sequence in the Mesopotamian basin, Iraq. J. Pet. Geol. 1998, 21, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafeet, H.A.; Handhal, A.M.; Raheem, M.K.H. Microfacies and depositional analysis of the Mishrif Formation in selected wells of Ratawi oilfield, Southern Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2020, 53, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Guo, L.N.; Li, C.; Tong, Y. Karstification characteristics of the Cenomanian–Turonian Mishrif Formation in the Missan Oil Fields, southeastern Iraq, and their effects on reservoirs. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 16, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Wang, Z.B.; Guo, L.N.; Wang, L.; Qi, M.M. Multi-parameters quantitative evaluation for carbonate reservoir based on geological genesis. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2019, 41, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.T.; Ding, Z.P.; Ao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J. Manufacturing method of large-scale fractured porous media for experimental reservoir simulation. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 2013, 18, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.T. Methodology for horizontal well pattern design in anisotropic oil reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2008, 35, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.C.; Nie, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, L.Z.; Zhang, B.J.; Feng, Y. Research on the method of recoverying microtopography of epeiric carbonate platform in depositional stage: A case study from the layer A of Jia 2 2 Member in Moxi Gas Field, Sichuan Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2011, 29, 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, D.; Salicioni, F.; Ucan, S. Cyclic water injection in San Jorge Gulf Basin, Argentina. In Proceedings of the SPE Latin America and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, Maracaibo, Venezuela, 21–23 May 2014. Paper number SPE-169403-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.J.; Liu, Y.Z.; Yao, J.; Huang, Z. Mechanistic study of cyclic water injection to enhance oil recovery in tight reservoirs with fracture deformation hysteresis. Fuel 2020, 271, 117677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyib, D.; Al-Qasim, A.; Kokal, S.; Huseby, O. Overview of Tracer Applications in Oil and Gas Industry. In Proceedings of the SPE Kuwait Oil & Gas Show and Conference, Mishref, Kuwait, 13–16 October 2019. Paper number SPE-198157-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Shook, G.M.; Pope, G.A.; Kazuhiro, A. Determining reservoir properties and flood performance from tracer test analysis. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 4–7 October 2009. Paper number SPE-124614-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, W.; Pi, J.; Qi, C. The method and strategy to optimize well density for oilfield development projects in technical service contract framework. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–12 November 2020. Paper number SPE-203067-MS. [Google Scholar]

| Sublayer | Thickness, m | Vertical Grid Number | Permeability, mD | Porosity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 6 | 3 | 522 | 17.4 |

| II | 8 | 4 | 54 | 18.4 |

| III | 18 | 9 | 13 | 17.1 |

| IV | 4 | 2 | 17 | 16.5 |

| V | 4 | 2 | 24 | 20.6 |

| VI | 10 | 5 | 15 | 15.9 |

| VII | 4 | 2 | 123 | 19.8 |

| VIII | 18 | 9 | 8 | 13.5 |

| Target Reservoir | Physical Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sublayer | Thickness, m | Porosity, % | Permeability, mD | Sublayer | Thickness, cm | Porosity, % | Permeability, mD |

| MB21-I | 5.5 | 18.0 | 41.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 18.0 | 4566 |

| MB21-II | 10.4 | 18.0 | 9.6 | 2 | 1.3 | 18.0 | 1064 |

| MB21-III~VI | 37.0 | 16.9 | 5.1 | 3 | 4.8 | 16.9 | 569 |

| MB21-VII | 3.1 | 19.7 | 12.5 | 4 | 0.4 | 19.7 | 1385 |

| MB21-VIII | 27.5 | 13.5 | 3.4 | 5 | 3.5 | 13.5 | 377 |

| Pattern Phase | Injection to Production Well Ratio | Field Water Cut Stage | Target VRR | Pressure Recovery Target, Psi/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 0.38 | <20% | 1.1~1.3 | 90 |

| Phase 2 | 0.24 | 20%~40% | 1.0~1.1 | 40 |

| Phase 3 | 0.53 | 40%~60% | 0.9~1.0 | 10 |

| Phase 4 | 0.86 | >60% | 0.9~1.0 | <10 |

| Method | Injector | Corresponding Producer | Permeability, mD | Channel Volume, m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean residence time method | B42 | B16 | 386 | 1361 |

| B49 | 82 | 4203 | ||

| Streamline model simulation | B16 | 134 | 1750 | |

| B49 | 21 | 5400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chen, P.; Na, R.; Li, C.; Pi, J.; Song, W. Integrated Understandings and Principal Practices of Water Flooding Development in a Thick Porous Carbonate Reservoir: Case Study of the B Oilfield in the Middle East. Processes 2025, 13, 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092921

Zhang Y, Chen P, Na R, Li C, Pi J, Song W. Integrated Understandings and Principal Practices of Water Flooding Development in a Thick Porous Carbonate Reservoir: Case Study of the B Oilfield in the Middle East. Processes. 2025; 13(9):2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092921

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu, Peiyuan Chen, Risu Na, Changyong Li, Jian Pi, and Wei Song. 2025. "Integrated Understandings and Principal Practices of Water Flooding Development in a Thick Porous Carbonate Reservoir: Case Study of the B Oilfield in the Middle East" Processes 13, no. 9: 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092921

APA StyleZhang, Y., Chen, P., Na, R., Li, C., Pi, J., & Song, W. (2025). Integrated Understandings and Principal Practices of Water Flooding Development in a Thick Porous Carbonate Reservoir: Case Study of the B Oilfield in the Middle East. Processes, 13(9), 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092921